Abstract

Background

This study examined the relative impact of familial and non-familial smoking on participant smoking and nicotine dependence.

Methods

This is a longitudinal study of 838 African American and Puerto Rican participants who were interviewed four times in their homes over a 15–16-year period (1990, 1994–1996, 2000–2001, and 2004–2006).

Results

Parental smoking during adolescence had a direct positive path to peer smoking during adolescence, which in turn had a direct positive path to participant smoking during the mid-twenties. In addition to the direct path between participant smoking in the mid-twenties and participant nicotine dependence during the late twenties, there was an indirect effect mediated by partner’s problems resulting from smoking during the late twenties.

Conclusions

This research demonstrates the key role the social environment plays in smoking and nicotine dependence. Both familial and non-familial smoking were significantly related to smoking and nicotine dependence. Public health implications suggest the importance of targeting prevention and treatment policies based on the participants’ stage of development. During adolescence the focus should be on parental and peer smoking, whereas during the twenties attention might be paid to their own smoking and that of their partners.

Keywords: Smoking, Nicotine Dependence, Social Environment

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1 Epidemiology and Consequences of Smoking

Tobacco continues to be the primary preventable cause of death in the United States (U.S.), resulting in approximately 440,000 deaths per year, with most adult smokers initiating tobacco use prior to age 18 (Center for Disease Control {CDC}, 2006a). According to the CDC (2006b), approximately 20% of adults, 23% of high school students, and 8% of middle school students in the U.S. currently smoke cigarettes. Smoking is often accompanied by wide-ranging adverse physical and mental health, social, developmental, cognitive, and economic consequences (Daigle, 2002). Smoking-related health issues include cardiovascular diseases, respiratory diseases, and cancer (CDC, 2006a). In Healthy People 2010, the federal government clearly delineates tobacco control as a national priority (Warner, 2001).

Nicotine is one of the most addictive drugs, especially when it enters the body through smoking tobacco (Breslau et al., 1993; Breslau et al., 2001; Kendler et al., 1999). Given the public’s concern with the adverse consequences of smoking, researchers have focused on identifying the predictors of smoking, particularly among adolescents. The overall goals are to develop programs that prevent people from initiating smoking, enable individuals to abstain from smoking, and encourage smoking cessation.

According to Family Interactional Theory (FIT) and Social Cognition Theory, social environments may be related to smoking behavior in adolescents and adults (Bandura, 1965; Brook et al., 1990). In accord with these theoretical frameworks, both the familial and non-familial environments may be associated with smoking behavior. The familial environment refers to the environment one is born into and includes parental smoking. The non-familial environment refers to the environment one selects and includes peer and partner smoking. As noted above, there is a body of research that indicates that peer smoking predicts participant smoking and/or nicotine dependence (e.g., Johnson and Hoffman, 2000; Mayhew et al., 2000). According to these theories, parents, peers, and partners may play a role in the individuals’ smoking by presenting models of smoking behavior and providing social reinforcement for smoking.

According to FIT, the determinants of nicotine dependence are influenced by several sets of social environments, including, but not limited to parental, peer, and partner smoking behavior. An important distinguishing feature of FIT is that these three social environments are not presumed to act in a parallel fashion. Instead, FIT assumes that parental smoking characteristics affect nicotine dependence in offspring through its effects on social environmental factors such as peer and partner smoking behavior.

Operating within a developmental perspective, FIT assumes that having early models of friends who smoke is related to the individual’s smoking at a later stage of development. The individual is then more likely to select partners who smoke. The operation of these two mechanisms, modeling and selection, viewed within a developmental framework, set the stage for a mediational model in which early peer smoking predicts later smoking in the individual, which, in turn, is associated with the selection of partners who smoke.

The family plays a crucial role in the individual’s development. The familial environment may set the stage for the individual to engage with peers who smoke. Therefore, a second aspect of the mediational model suggests that adolescents who have parents who smoke are more likely to be in environments that include other smokers, specifically friends who smoke. As noted above, young adults are more likely to smoke and select partners who smoke. Therefore, FIT proposes a mediational model since it assumes that family factors are mediated by peers, personality attributes, and partners which in turn are related to nicotine dependence (Brook et al., 1990).

1.2 Familial and Non-Familial Smoking as Related to the Individual’s Smoking and Nicotine Dependence

Research has demonstrated that earlier parental and peer smoking as well as partner smoking predict the individual’s smoking and nicotine dependence. However, the interrelationships among these factors have not been established in the literature. Research has shown that a history of familial smoking predicts peer smoking and the individual’s smoking and nicotine dependence later on in life. For example, among white adolescents and adults, Brook et al. (2008) reported that peer smoking mediates the relationship of parental smoking and later nicotine dependence. In contrast, several researchers have noted that a history of parental smoking is directly related to later participant smoking (i.e., Bricker et al., 2006; Brook et al., 2006; Engels and Knibbe, 1999; Exter Blokland et al., 2003; Fergusson et al., 2007). In addition, research has shown a direct relationship between non-familial smoking and the participant’s smoking later on in life. For example, peer smoking has been found to be related to a young adult's smoking (i.e., Bricker et al., 2006; Brook et al., 2006; Fergusson et al., 2007).

According to the literature, earlier smoking is related to later nicotine dependence (Breslau et al., 1993; Breslau et al., 2001; Kendler et al., 1999; Patton et al., 2006). In addition to a direct relationship, this relationship is also mediated by partner smoking during young adulthood (Homish and Leonard, 2005; Ockene et al., 2002). Therefore, we hypothesize a direct and indirect (mediated by partner smoking during young adulthood) relationship between earlier smoking in young adulthood and later nicotine dependence in young adulthood.

Although many studies have examined the impact of familial and non-familial smoking (parental, peer, and partner) during adolescence and young adulthood on smoking and nicotine dependence during young adulthood, few studies have examined the relative impact of familial versus non-familial smoking on the individual’s dependence on nicotine.

Some studies found that parental and peer smoking during the participant’s adolescence has an equal impact on the participant’s smoking during young adulthood (i.e., Bricker, et al., 2006; Brook et al. 2006; Fergusson et al., 2007). In contrast, some studies found that parental smoking had a greater impact than peer smoking (i.e., Bogart et al., 2006; Brook et al., 1997; Engels and Knibbe, 1999), while other studies found that peer smoking had a greater impact than parental smoking (i.e., Ellickson et al., 2003; Monden et al., 2003). According to our knowledge, no studies have included the relative impact of parent, peer, and partner smoking on the participant’s dependence on nicotine. The present study was designed to fill this gap in the literature. Based on the above-cited literature, we hypothesize that non-familial smoking (i.e., peer and partner) will have a greater impact than familial smoking (i.e., parent) on the likelihood of participant smoking and nicotine dependence.

1.3 Gender and Ethnicity and the Individual’s Smoking

There is the suggestion from the literature that Puerto Ricans are more likely to be nicotine dependent than African Americans because of cultural norms or structural barriers and supports (Mermelstein and The Tobacco Control Network Writing Group, 1999). To date, the empirical results regarding differences in pathways to nicotine dependence in African Americans and Puerto Ricans are not available. Consequently, exploration of the pathways to nicotine dependence in these two minority groups is needed. Although it is beyond the scope of the present investigation to develop separate culturally specific models, we do assess whether the pathways to nicotine dependence differ between African Americans and Puerto Ricans.

Although the literature on gender differences in smoking and nicotine dependence is relatively sparse, the evidence does suggest that there is greater smoking by males than by females. This may relate to the negative views of smoking by females in certain cultures. A qualitative study using focus groups by Mermelstein and The Tobacco Control Network Writing Group (1999) regarding the ethnic and gender differences in youth smoking found that minority groups concurred that it was not appropriate for females to smoke. For African American and Puerto Rican women, there was an added belief that smoking would taint their reputation. In addition, African American women believed that smoking has a detrimental impact on appearance and hygiene and is viewed as risky behavior. Therefore, we hypothesize that compared to females, males are more likely to report that they are nicotine dependent.

In summary, we hypothesize that: (1) parental and peer smoking are related to young adult smoking, which in turn predicts later nicotine dependence; (2) partner smoking mediates between participant smoking and later nicotine dependence; (3) participant smoking will have a direct effect, and has a significant impact on participant nicotine dependence during young adulthood; (4) non familial (peer and partner) smoking will have a greater impact than familial (parental) smoking on smoking and nicotine dependence; and (5) African American and Puerto Rican males are more likely than African American and Puerto Rican females to be dependent on nicotine. This study adds to the literature by examining the 1) long-term effects of different societal influences (familial versus non-familial), 2) relative effects of familial (parental) and non-familial (friends and partner) smoking, 3) different ethnic groups, and 4) effects of earlier smoking on later nicotine dependence.

2. Methods

2.1 Sample and Procedure

The present study is based on a four-wave longitudinal study of African American and Puerto Rican participants. The time 1 sample (T1, N = 1,332) was collected in 1990, time 2 (T2, N = 1,190) in 1994–1996, time 3 (T3, N = 660) in 2000–2001, and time 4 (T4, N = 838) in 2004–2006. The mean ages of the sample were 14.0 (SD = 1.3) at T1, 19.1 (SD = 1.5) at T2, 24.4 (SD = 1.3) at T3, and 29.2 (SD = 1.7) at T4. Participants at T1 were 7th to 10th graders in 11 schools serving the East Harlem area of New York City. We selected this school district in order to obtain a large sample of African American (N = 694) and Puerto Rican (N = 636) urban youth. Two participants were dropped from the study after T1, as we discovered they had missing data on ethnicity.

The present study included 838 participants. Fifty-nine percent (N = 498) of the sample were female and 41% (N = 340) were male. There were 460 (55%) African American and 378 (45%) Puerto Rican participants. To analyze attrition effects in this sample from T1 to T4, several t-tests and χ2 tests were conducted. The results of the attrition analyses showed significant differences for both gender (χ2(1)=28.87, p<0.05) and ethnicity (χ2(1)=7.53, p<0.05), but not for the psychosocial variables such as peer smoking at T1 (t=1.48, p>0.05), paternal smoking at T1 (χ2(1)=1.32, p>0.05), and maternal smoking at T1 (χ2(1)=0.93, p>0.05), between those who were interviewed at baseline and at T4 and those who were not.

The T1 data was collected in classrooms via personal tape players and the T2 and T3 data were collected via in-person interviews. At T3 a subsample of the original cohort was randomly selected due to budgetary constraints (N = 660). The T4 data collection employed mail (N = 345, 41%), phone (N = 182, 22%), and in-person (N = 311, 37%) interviews due to budget constraints. However, there were no significant differences in the participants’ nicotine dependence as a result of the different data collection approaches used (χ2 (2) =1.21, p>0.05). We used the SAS MI procedure to deal with missing data on a variable by variable basis. The SAS MI procedure calculates the maximum likelihood estimates of the missing values (i.e., Full Information Maximum Likelihood on a variable by variable basis).

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) for the Mount Sinai School of Medicine approved the study’s procedures (prior to 2004), and the New York University School of Medicine’s IRB approved the study from 2004 onward. A Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained from the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 History of Parental Smoking

The latent variable of a history of parental (maternal and paternal) smoking consisted of four separate items and asked whether the participant’s mother and father smoked cigarettes on a regular basis at T1 and T2 (earlier and later adolescence). Answer options included (1) “No” and (2) “Yes” (Brook et al., 1990).

2.2.2 Peer Smoking

The latent variable of peer smoking consisted of two separate items and asked how many of the participant’s friends regularly smoked cigarettes at T1 and T2 (earlier and later adolescence). Answer options included (1) “None,” (2) “A Few,” (3) “Only Some,” and (4) “Most” (Johnston et al., 2007).

2.2.3 Partner’s Problems Resulting from Smoking

The measure of partner’s problems resulting from smoking asked whether the participant’s spouse, partner, girlfriend, or boyfriend experienced problems resulting from cigarette smoking at T4. Answer options for the partner’s problems resulting from smoking included (0) “No” and (1) “Yes” (Endicott, personal communication, 1999).

2.2.4 Participant Smoking

Three measures of participant smoking were assessed at T3. The measures included the following: 1) In the past 5 years how many cigarettes did you smoke?; 2) What was the greatest number of cigarettes you ever smoked?; and 3) How many cigarettes do you smoke? Answer options for each measure included: (1)“None,” (2) “A few cigarettes or less a week,” (3) “1–5 cigarettes a day,” (4) “About half a pack a day,” (5) “About one pack a day,” (6) “About one and a half packs a day,” and (7) “More than one and a half packs a day” (Marcus et al., 2007).

2.2.5 Participant Current Nicotine Dependence

The nicotine dependence measure, according to the definition of DSM IV-TR, was ascertained by the presence of three or more of the following symptoms for nicotine dependence during the 12-month period prior to the interview: 1) such a strong desire or urge to use tobacco that the respondent could not refrain from using it; 2) the development of physical tolerance for nicotine, so that the participant was able to smoke more without experiencing negative effects; 3) tobacco was consumed in larger amounts or over a longer duration than was originally intended; 4) the duration of a month or more when the respondent interrupted activities like sports, work, or associating with friends and family in order to smoke; 5) the duration of several days or more when the respondent chain-smoked; 6) difficulty stopping or cutting down on smoking; and 7) continuous use even though the participant experienced the presence of emotional or psychological problems as a result of tobacco use. The questions were similar to the questions used in the University of Michigan version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (Kessler et al., 1998) and in the National Comorbidity Survey (Kessler, 1994). They were altered to be consistent with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition, TR version (American Psychiatric Association {APA}, 2000). Approximately 23% (194 out of 838) of the participants met the criteria for a diagnosis of nicotine dependence. All scales described above had predictive validity (Brook et al., 1990; Kessler, 1994; Kessler et al., 1998).

2.3 Data Analysis

A structural equation model (SEM) was used to test the hypothesized pathways delineated in the Introduction. Computations were performed using LISREL 8.4 (Jöeskog and Söbon, 1996). To account for the non-normal distribution of the model variables, we used the Satorra-Bentler scaled statistic (S-B χ2) (Satorra and Bentler, 1998) as the test statistic for model evaluation, as recommended by Hu, Bentler and Kano (1992). We used the goodness of fit index (GFI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the Bentler’s comparative fit index (CFI) to assess the empirical model. Finally, a total effect analysis was conducted to assess the relative potency of each of the latent constructs.

We then tested whether the pathways to adult nicotine dependence were the same for males and females and for African Americans and Puerto Ricans. We first tested whether the measurement coefficients were the same across the groups. In the event that the measurement coefficients were not statistically or clinically different across the groups, we then tested whether the structural coefficients (i.e., the pathways) were the same.

2.4 Results

Table 1 presents gender and ethnic differences in smoking, nicotine dependence, and the familial and the non-familial smoking environment. As shown in Table 1, Puerto Ricans as compared to African Americans reported significantly higher percentages of current daily smoking, daily smoking in the past five years, ever daily smoking, and paternal and peer smoking. Males as compared to females reported significantly higher percentages of current daily smoking, daily smoking in the past five years, and ever daily smoking. However, we did not find significant gender and ethnic differences in adult nicotine dependence.

Table 1.

Gender and Ethnic Differences in Smoking, Nicotine Dependence, and Familial and Non-Familial Smoking Environment.

| Whole Sample |

Male | Female | African- American |

Puerto Rican |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paternal Smoking at T1e | 37.6% | 37.2% | 37.9% | 33.2% | 42.9% |

| Maternal Smoking at T1 | 33.6% | 34.1% | 33.2% | 30.7% | 37.0% |

| Most Friends Smoking at T1 e | 23.9% | 25.9% | 22.5% | 17.4% | 31.8% |

| Current Daily Smoking at T3 ge | 22.7% | 30.3% | 17.5% | 19.1% | 27.0% |

| Daily Smoking in the Past 5 Years at T3 ge |

27.8% | 35.0% | 22.9% | 23.0% | 33.6% |

| Ever Daily Smoking at T3 ge | 33.3% | 40.3% | 28.5% | 28.3% | 39.4% |

| Partner’s Problems Resulting From Smoking at T4 |

19.3% | 19.1% | 19.5% | 19.6% | 19.1% |

| Nicotine Dependence at T4 | 23.2% | 25.9% | 21.3% | 21.3% | 25.4% |

Note: Most friends as compared to fewer friends

gender differences were statistically significant (χ2 test, p<0.05)

ethnic differences were statistically significant (χ2 test, p<0.05).

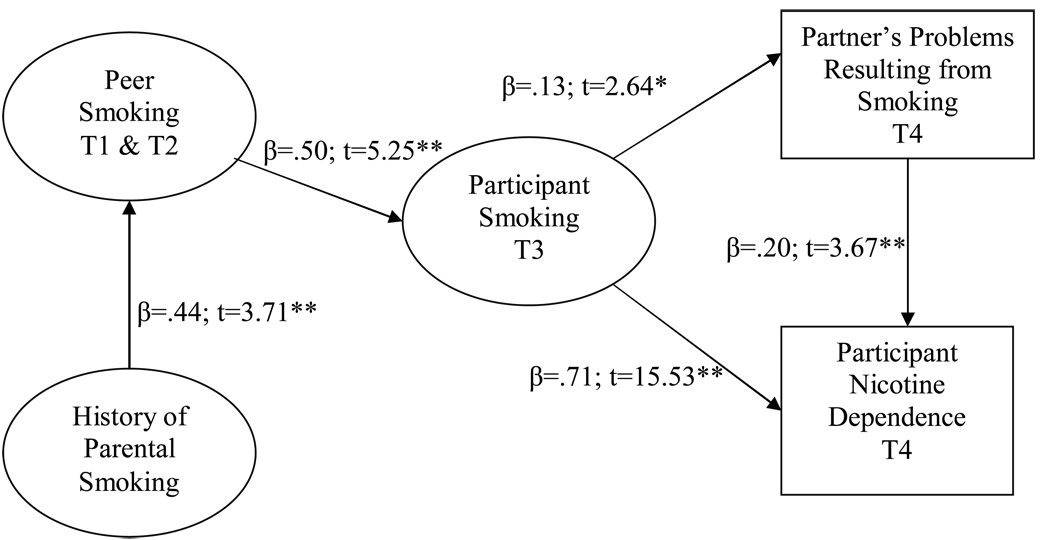

Using LISREL VIII, we tested the measurement model as well as the structural model. All factor loadings were significant (p<0.001). Therefore, the findings showed that the indicator variables were satisfactory measures of the latent constructs. The following fit indices were obtained: GFI=0.99; RMSEA=0.012; and Bentler’s CFI=0.99. These results reflect a satisfactory model fit. For the structural model, standardized parameter estimates, as well as the associated t - statistics for the sample, are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The Standardized Empirical Pathways of the Structural Equation Model

Note: 1) *p<0.01; **p<.001, two-tailed test;

2) GFI=.99; CFI=.99;

3) T1=Time 1 =mean age 14.0=early adolescence,

T2=Time 2 =mean age 19.1=late adolescece,

T3=Time 3 =mean age 24.4=mid-twenties,

T4=Time 4 =mean age 29.2=late twenties.

As noted in Figure 1, the developmental model, as hypothesized in the Introduction, was supported. The obtained model had the following significant pathways (p ≤ 0.05; two-tailed test):

A history of parental smoking at T1 and T2 had a direct positive path to peer smoking at T1 and T2 (β=.44, t=3.71) and an indirect positive path to participant smoking at T3 (β=.50, t=5.25)

Participant smoking at T3 had a direct positive path to participant nicotine dependence at T4 (β=.71, t=15.53), as well as a direct positive path to the problems resulting from partner smoking at T4 (β=.13, t=2.64); and

Problems resulting from partner smoking at T4 had a direct positive path to participant nicotine dependence at T4 (β=.20, t=3.67).

Table 2 presents the result of the total effects analysis for each of the latent constructs on the participant’s nicotine dependence at T4. The standardized total effects indicate that the participant’s smoking at T3 had the largest total effects on the participant’s nicotine dependence at T4 (β=0.74, t=14.46). The total effects of the other two non-familial latent constructs (i.e., peer smoking at T1 and T2 and problems resulting from partner smoking at T4) on the participant’s nicotine dependence at T4 were statistically significant [β=0.37 (t=4.83) and β=0.20 (t=3.67), respectively]. The total effect of the familial environment (i.e., a history of parental smoking at T1 and T2) on the participant’s nicotine dependence was also statistically significant [β=0.16 (t=3.68)], although of a lesser magnitude.

Table 2.

Standardized Total Effects and Their t-test Statistics.

| Domains | T4 Nicotine Dependence |

|---|---|

| Parental Smoking at T1 and T2 | .16 (t=3.68)** |

| Peer Smoking at T1 and T2 | .37 (t=4.83)** |

| Partner’s Problems Resulting from Smoking at T4 | .20 (t=3.67) ** |

| Participant Smoking at T3 | .74 (t=14.46) ** |

Note: *p<0.01; **p<.001, two-tailed test

T1=Time 1 =mean age 14.0=early adolescence

T2=Time 2 =mean age 19.1=late adolescence

T3=Time 3 =mean age 24.4=mid-twenties

T4=Time 4 =mean age 29.2=late twenties.

We then tested whether the structural models were the same for African Americans and Puerto Ricans, and for males and females. To compare the African American and Puerto Rican structural models, first, we constrained the measurement model parameters and structural model parameters to be equal for both ethnic groups. We then allowed the measurement coefficients to differ for African Americans and Puerto Ricans. There were no statistically significant differences in the measurement coefficients between African Americans and Puerto Ricans (χ2 (4) = 1.91, p>.05), and all of the coefficients were statistically significant within each group. We then allowed the structural coefficients to differ for African Americans and Puerto Ricans. The results showed that none of the differences in the structural coefficients were statistically significant (χ2 (5) = 2.84, p>.05). Using the same procedure, we compared the male and female structural models. There were no statistically significant differences in the measurement coefficients between males and females (χ2 (4) = .97, p>.05), and all of the coefficients were statistically significant within each group. We then allowed the structural coefficients to differ for males and females. The results showed that none of the differences in the structural coefficients were statistically significant (χ2 (5) = 1.72, p>.05). Based on these findings, we concluded that the African American and Puerto Rican models, and the male and female models, do not appear to be structurally different.

3. Discussion

This is the first prospective study to examine the relative impact of familial (i.e., parents) and non-familial (i.e., peers) smoking on African American and Puerto Rican young adult’s smoking and nicotine dependence.

The results supported our major hypotheses. First, our findings indicate that adolescent peer smoking mediated the relationship between a history of parental smoking during adolescence and the participant’s smoking during the mid-twenties. Second, there were direct effects of both the participant’s smoking during the mid-twenties and the partner’s problems resulting from smoking during the late twenties on the participant’s nicotine dependence during the late twenties. Third, our findings indicated that the partner’s problems resulting from smoking during the late twenties mediated the relationship between the participant’s smoking during the mid-twenties and the participant’s nicotine dependence during the late twenties. Fourth, although during the mid-twenties, males were more likely than females to smoke and Puerto Ricans were more likely than African Americans to smoke, there were no significant gender or ethnic differences in nicotine dependence.

This research further adds to a growing base of knowledge assessing social environmental factors that support or prohibit nicotine dependence. Based on the model derived from FIT and Social Cognition Theory (Bandura, 1965; Brook et al., 1990), our analyses tested the conceptual model assessing the contributions of family and peers to nicotine dependence, as well as the partner’s problems resulting from smoking and nicotine dependence. Overall, the results suggested that nicotine dependence was predicted by both direct (i.e., the participant’s smoking and the partner’s problems resulting from smoking) and indirect factors (i.e., earlier parental and peer smoking). Moreover, similarities were found between African Americans and Puerto Ricans in the pathways to nicotine dependence. Our findings concerning the interplay between specific environmental factors add to our comprehension of how the social environment in minority populations leads to nicotine dependence. The latter has become a central concern for policy makers, researchers, and practitioners (Brook, Pahl, & Brook, 2008).

Partners appeared to act as a mediator through which family, peer, and the participant’s smoking were related to the participant’s nicotine dependence. Partners often have an important influence over their significant other. The partner may provide the participant with cigarettes (Homish and Leonard, 2005). On the other hand, the partner may provide the necessary support to help the participant abstain from smoking (Ockene et al., 2002).

Consistent with Fergusson and colleagues (Fergusson, Horwood, Boden, & Jenkin, 2007), we found that both familial and non-familial domains had effects on the participant’s smoking, and ultimately on the participant’s nicotine dependence. This may highlight the long-term effects of modeling behavior and social reinforcement from both the familial and non-familial environments on later nicotine dependence. Both the familial and non-familial environments predicted the participant’s smoking and nicotine dependence, but the peer’s smoking had the most powerful effect on the participant’s smoking and nicotine dependence.

The non-familial environment (i.e., peer and partner’s problems resulting from smoking) plays a significant role in later participant smoking and nicotine dependence. It is possible that several hypothetical mechanisms are at play. These may include selection, imitation, and reinforcement. For example, adolescents may first decide to initiate smoking and then choose friends who share that value. Several investigators (e.g., Vink et al., 2003; Vries et al., 2003) have noted that once such friendships are formed, peers may reinforce smoking behavior. In a related manner, individuals who smoke may select partners who smoke (Homish and Leonard, 2005).

Nevertheless, the familial environment plays a significant role in later participant smoking and nicotine dependence. Family dynamics and modeling are important in the acquisition of child/adolescent daily smoking (O'Loughlin et al., 1998; Peterson et al., 2006). The impact of parental smoking may be attributed to social observational learning and role modeling of health compromising behaviors (Oygard et al., 1995; Shamsuddin and Haris, 2000).

Consistent with the literature (i.e., Mermelstein and The Tobacco Control Network Writing Group, 1999; Patton et al., 2006), the findings of this study indicated that males were more likely to smoke than females. Furthermore, Puerto Ricans were more likely to smoke than African Americans. However, the pathways to nicotine dependence in African Americans are similar to the pathways to nicotine dependence in Puerto Ricans. In a related vein, the pathways to nicotine dependence are similar in males and females. This might imply that the model for pathways to nicotine dependence are generalizable across ethnic and gender groups. Nevertheless, smoking interventions need to be relevant to culture, language, and gender.

The present study has several limitations. First, because the study was conducted with an inner-city African American and Puerto Rican cohort, the findings need to be replicated with diverse ethnic populations (e.g., Asians and Whites) to establish the generalizibilty of the causal model. Contrary to our findings, there is evidence that among African Americans the family plays a more important role than the peer group with respect to the individual’s smoking (Dornelas et al., 2005; Ellickson et al., 2004; Ellickson et al., 2003). The differences between the studies may be due to different comparison groups. Consequently, the relative importance of parents and peers as related to the individual’s smoking warrants further investigation. Second, with regard to familial factors, parental style (e.g., parent-child conflict) is related to both parental smoking and the participants’ risk behaviors (Chassin et al., 2005; Doherty and Allen, 1994). Future research might include parenting styles (e.g., parental warmth, control) in their models for a more complete understanding of the pathways to nicotine dependence. Third, the study is based on self-reports. Objective measurements allow for more precise and reliable assessment. For instance, no use of biochemical validation was applied. However, there is evidence that there is fairly good concordance between self-report of smoking and biochemical assessments (Klebanoff et al., 1998). Fourth, in our study, there are greater rates of attrition among Puerto Ricans and males. Future studies might explore the use of incentives which are more relevant to culture, language, and gender in order to encourage participation. Despite these limitations, the results of this investigation provide important new evidence regarding the relative impact of the familial versus non-familial environments during adolescence on smoking and nicotine dependence during young adulthood.

3.1 Policy and Clinical Implications

This research has policy and clinical implications. The results illuminate the effects of the familial (parental) and non-familial (peer and partner) environments during adolescence and young adulthood on smoking and nicotine dependence during young adulthood. Non-familial smoking, specifically the peer’s smoking, had a strong relationship with the participant’s nicotine dependence. In order to prevent nicotine dependence, policies and treatment need to focus on all three aspects of the individual’s social environment: parent, peer, and partner smoking. Interventions should be geared towards the specific individual’s developmental stage; parent and peer smoking during adolescence, participant smoking during the mid-twenties, and problems resulting from the partner’s smoking during the late twenties.

Policy and prevention programs should focus on the power of the partner’s influence on smoking, and the partner’s potentially powerful role in the participant’s smoking cessation. The study suggests the significance of selection, susceptibility to modeling, and reinforcement of smoking by partners and peers. The study also elucidates the mechanism of selection of the participant’s partner. The mechanisms of modeling and selection of partners and peers may require different emphases in preventive and clinical interventions. Prevention and intervention programs can also have an effect on the decision-making process of peer selection (e.g., peer pressure).

In intervention programs for parents, one should include the importance of parents’ communicating anti-smoking rules and behaviors to their offspring. Family dynamics and modeling are important in the acquisition of child/adolescent daily smoking. Observational learning and the negative role model of parental smoking within the home environment need to be addressed when developing smoking prevention programs geared toward adolescents. Parents should be informed that their own smoking increases the risk of their child initiating smoking and becoming a daily smoker. Helping parents stop or refrain from initiating smoking may be beneficial for their children.

In sum, the findings support a developmental model, which demonstrates how earlier adolescent family factors may have detrimental effects on non-familial factors and subsequent nicotine dependence in adults. This research provides support for the critical need for policy and prevention efforts to employ a multidimensional developmental approach that focuses on different aspects of the social environment (familial and non-familial) in order to prevent later smoking and dependence on nicotine.

References

- American Psychiatric Association (APA) Text Revision DSM-IV-TR. Fourth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Influence of models' reinforcement contingencies on the acquisition of imitative responses. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1965;1:224–231. doi: 10.1037/h0022070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogart LM, Collins RL, Ellickson PL, Klein DJ. Adolescent predictors of generalized health risk in young adulthood: A 10-year longitudinal assessment. Journal of Drug Issues. 2006;36:571–596. [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Fenn N, Peterson EL. Early smoking initiation and nicotine dependence in a cohort of young adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1993;33:129–137. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(93)90054-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Johnson EO, Hiripi E, Kessler R. Nicotine dependence in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:810–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.9.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricker JB, Peterson AV, Anderson MR, Leroux BG, Rajan KB, Sarason IG. Close friends', parents', and older siblings' smoking: Reevaluating their influence on children's smoking. Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8:217–226. doi: 10.1080/14622200600576339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Brook DW, Gordon AS, Whiteman M, Cohen P. The psychological etiology of adolescent drug use: A family interactional approach. Genet Soc Gen Psychol Monogr. 1990;116:111–267. (entire monograph) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Pahl K, Ning Y. Peer and parental influences on longitudinal trajectories of smoking among African Americans and Puerto Ricans. Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8:639–651. doi: 10.1080/14622200600789627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Whiteman M, Czeisler LJ, Shapiro J, Cohen P. Cigarette smoking in young adults: Childhood and adolescent personality, familial, and peer antecedents. J Genet Psychol. 1997;158:172–188. doi: 10.1080/00221329709596660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Pahl K, Brook DW. Tobacco use and dependence. In: Essau CA, editor. Epidemiology, Assessment, and Treatment. New York: Elsevier, Inc; 2008. pp. 149–177. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control (CDC) [Retrieved January 17, 2008];Tobacco Information and Prevention Source (TIPS) 2006a from www.cdc.gov/tobacco/issue.htm.

- Center for Disease Control (CDC) [Retrieved January 17, 2008];Smoking prevalence among U.S. adults. 2006b from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5644a2.htm.

- Chassin L, Presson CC, Rose J, Sherman SJ, Davis MJ, Gonzalez JL. Parenting style and smoking-specific parenting practices as predictors of adolescent smoking onset. J Pediatr Psychol . 2005;30:333–344. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daigle J. [Retrieved January 17,2008];Leadership in Substance Abuse Treatment and Recovery. 2002 from http://partnersforrecovery.samhsa.gov/docs/Daigle_Leadership_Paper_4-14-2005.pdf.

- Doherty WJ, Allen W. Family functioning and parental smoking as predictors of adolescent cigarette use: A six-year prospective study. J Fam Psychol. 1994;8:347–353. [Google Scholar]

- Dornelas E, Patten C, Fischer E, Decker PA, Offord K, Barbagallo J, Pingree S, Croghan I, Ahluwalia JS. Ethnic variation in socioenvironmental factors that influence adolescent smoking. J Adolesc Health. 2005;36:170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellickson PL, Orlando M, Tucker JS, Klein DJ. From adolescence to young adulthood: racial/ethnic disparities in smoking. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:293–239. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.2.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellickson PL, Perlman M, Klein DJ. Explaining racial/ethnic differences in smoking during the transition to adulthood. Addict Behav. 2003;28:915–931. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00285-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engels RCME, Knibbe RA. Influences of parental and best friends' smoking and drinking on adolescent use: A longitudinal study. J Appl Psychol . 1999;29:337–361. [Google Scholar]

- Exter Blokland EAW, Engels RCME, Hale WW, Meeus W, Willemsen MC. Lifetime parental smoking history and cessation and early adolescent smoking behavior. Prev Med. 2003;38:359–368. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Boden JM, Jenkin G. Childhood social disadvantage and smoking in adulthood: Results of a 25-year longitudinal study. Addiction. 2007;102:475–482. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homish GG, Leonard KE. Spousal influence on smoking behaviors in a U.S. community sample of newly married couples. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:2557–2567. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM, Kano Y. Can test statistics in covariance structure analysis be trusted? Psychol Bull. 1992;112:351–362. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.2.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R, Hoffman J. Adolescent cigarette smoking in US racial/ethnic subgroups: Findings from the National Education Longitudinal Study. J Health Soc Behav. 2000;41:392–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2006. 2007 (Vol. I: Secondary school students [NIH Publication no. 07-6205])

- Jöeskog KG, Sörbon D. Chicago: Chicago, Scientific Software International; LISREL 8: User's Reference Guide. 1996

- Kendler KS, Neale MC, Sullivan P, Corey LA, Gardner CO, Prescott CA. A population-based twin study in women of smoking initiation and nicotine dependence. Psychol Med. 1999;29:299–308. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798008022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC. The National Comorbidity Survey: Preliminary results and future directions. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 1994;4:114.111–114.113. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Wittchen HU, Abelson JM, McGonagle K, Schwartz N, Kendler KS, Knauper B, Zhao S. Methodological studies of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) in the U.S. National Comorbidity Survey (NCS) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 1998;7:33–55. [Google Scholar]

- Klebanoff MA, Levine RJ, Clemens JD, DerSimonian R, Wilkins DG. Serum cotinine concentration and self-reported smoking during pregnancy. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148:259–262. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus SE, Pahl K, Ning Y, Brook JS. Pathways to smoking cessation among African American and Puerto Rican young adults. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:1444–1448. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.101212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayhew KP, Flay BR, Mott JA. Stages in the developmental of adolescent smoking. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;59 suppl 1:S61–S81. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00165-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mermelstein R The Tobacco Control Network Writing Group. Explanations of ethnic and gender differences in youth smoking: A multi-state, qualitative investigation. Nicotine Tob Res. 1999;1:S91–S98. doi: 10.1080/14622299050011661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monden CWS, Graaf ND, Kraaykamp G. How important are parents for smoking cessation in adulthood: An event history analysis. Prev Med. 2003;36:197–203. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(02)00026-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ockene JK, Ma Y, Zapka JG, Pbert LA, Valentine Goins K, Stoddard AM. Spontaneous cessation of smoking and alcohol use among low-income pregnant women. Am J Prev Med. 2002;23:150–159. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00492-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Loughlin J, Paradis G, Renaud L, Gomez LS. One-year predictors of smoking initiation and of continued smoking among elementary schoolchildren in multiethnic,low-income, inner-city neighbourhoods. Tob Control. 1998;7:268–275. doi: 10.1136/tc.7.3.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oygard L, Klepp KI, Tell GS, Vellar OD. Research Report: Parental and peer influences on smoking among young adults: Ten-year follow-up of the Oslo youth study participants. Addiction. 1995;90:561–569. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.90456110.x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Patton GC, Coffey C, Carlin JB, Sawyer SM, Wakefield M. Teen smokers reach their mid-twenties. J Adolesc Health . 2006;39:214–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson AV, Leroux BG, Bricker J, Kealey KA, Marek PM, Sarason IG, Andersen MR. Nine-year prediction of adolescent smoking by number of smoking parents. Addict Behav. 2006;31:788–801. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satorra A, Bentler PM. American Statistical Association 1988 Proceedings of the Business and Economic Sections. Alexandria, VA: American Statistical Association; 1998. Scaling corrections for chi-square in covariance structure analysis; pp. 308–313. [Google Scholar]

- Shamsuddin K, Haris MA. Family influence on current smoking habits among secondary school children in Kota Bharu, Kelantan. Journal of Singapore Medicine. 2000;41:167–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vink JM, Wilemsen G, Boomsma DI. The association of current smoking behavior with the smoking behavior of parents, siblings, friends, and spouses. Addiction. 2003;98:923–931. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vries HD, Engels R, Kremers S, Wetzels J, Mudde A. Parents' and friends' smoking status as predictors of smoking onset: Findings from six European countries. Health Education Research. 2003;18:627–636. doi: 10.1093/her/cyg032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner KE. Tobacco control policy: From action to evidence and back again. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20:2–5. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00299-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]