Abstract

The amyloid-β (Aβ) protein exists in the aging mammalian brain in diverse assembly states, including amyloid plaques and soluble Aβ oligomers. Both forms of Aβ have been shown to impair neuronal function, but their precise roles in Alzheimer’s disease (AD)-associated memory loss remain unclear. Both types of Aβ are usually present at the same time in the brain, which has made it difficult to evaluate the effects of plaques and oligomers individually on memory function. Recently, a particular oligomeric Aβ assembly, Aβ*56, was found to impair memory function in the absence of amyloid plaques. Until now it has not been possible to determine the effects of plaques, in the absence of Aβ oligomers, on memory function. We have identified Tg2576 mice with plaques but markedly reduced levels of Aβ oligomers, which enabled us to study the effects of plaques alone on memory function. We found that animals with amyloid plaques have normal memory function throughout an episode of reduced Aβ oligomers, which occurs during a period of accelerated amyloid plaque formation. These observations support the importance of Aβ oligomers in memory loss and indicate that, at least initially, amyloid plaques do not impair memory.

INTRODUCTION

The Aβ protein in the extracellular space of the brain can exist in two distinct states of aggregation — as insoluble, fibrillar structures residing in amyloid plaques, and as soluble, non-fibrillar oligomeric assemblies that are physically separate from plaques in AD brain (Kayed et al., 2003). Amyloid plaques and associated neuritic dystrophy have been shown to impact the function and microstructure of neurons in their immediate vicinity (Cummings et al., 1996, Knowles et al., 1999, Urbanc et al., 2002, Stern et al., 2004, Spires et al., 2005). In addition, recent evidence suggests that oligomeric Aβ assemblies may contribute to the pathogenesis of AD (Lambert et al., 1998, Hsia et al., 1999, Mucke et al., 2000, Ashe, 2001, Klein et al., 2001, Westerman et al., 2002, Lesne et al., 2006).

The difficulty with determining the exact role of fibrillar versus soluble Aβ species on memory is that in the aging brain both co-exist simultaneously and may interact with each other. Previously, we demonstrated the effect of endogenous soluble oligomeric Aβ assemblies, specifically Aβ*56, on memory function in the absence of amyloid deposition in the AD mouse model Tg2576 (Lesne et al., 2006). The purpose of the present study was to examine memory function in mice possessing amyloid plaques but having very low levels of oligomeric Aβ assemblies.

In Tg2576 mice, which overexpress human APP with the Swedish mutation (Hsiao et al., 1996), compact amyloid deposits comprised of Aβ40 and Aβ42 appear at 7-8 months of age (Kawarabayashi et al., 2001). Mature amyloid plaques consisting of dense cores surrounded by loosely packed Aβ fibrils appear at ~12 months (Hsiao et al., 1996, Kawarabayashi et al., 2001). Using Tg2576 mice, we measured different forms of cerebral Aβ and found that the levels of the Aβ oligomers in the extracellular-enriched fraction, including Aβ*56, were transiently lowered at ~12 months compared to previous months. The reduction in soluble Aβ oligomers coincided with the appearance of mature amyloid plaques and also with a period of accelerated accumulation of insoluble Aβ. While the levels of all the soluble Aβ oligomers were reduced, the Aβ*56 levels showed the largest reduction. Surprisingly, despite an increase in the fibrillar Aβ, the reduction in soluble oligomeric Aβ species was accompanied by a recovery of memory function. The data support previous studies showing the importance of Aβ*56 in memory dysfunction (Lesne et al., 2006), and also suggest that amyloid plaque formation early in AD may help to absorb the impact of Aβ*56 and other Aβ oligomers on brain function.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Transgenic animals

Heterozygous Tg2576 mice (Hsiao et al., 1996) on the 129S6FVBF1 background strain were utilized for biochemical and behavioral experiments. To ensure that each measurement was performed at the same age, separate cohorts of Tg2576 mice were used to complete the behavioral testing and the biochemical assays. Animal experiments were carried out in accordance with the National Institute of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publications No. 80-23) revised 1996.)

Behavioral tests

Spatial reference memory was assessed in 171 Tg2576 mice (94 female, 77 male) using a modified version of the Morris water maze (Westerman et al., 2002). Testing was tailored for Tg2576 in the 129S6FVBF1 background strain since these mice learn more rapidly than B6SJL mice. 10.7- and 11.8-month mice received visible platform training for 2 days, 6 trials per day and 12.0-, 12.5-, and 12.6-month mice received visible platform training for 3 days, 6 trials per day. Outliers in the final three trials of visible platform training with mean path lengths >3SD above the pooled non-transgenic (non-Tg) mean were excluded as performance incompetent mice (N=15). There was an insignificant effect of age on performance during the last three trials of visible platform training for both Tg2576 and non-Tg controls (data not shown). 10.7-month Tg2576 mice had slightly but significantly longer path lengths than non-Tg littermates during the final three visible trials (2.0m ± 0.13m vs 1.2 ± 0.11m; P<0.001). At all other ages Tg2576 and non-Tg littermates had equivalent performance during the final three visible trials (data not shown). Hidden platform training followed visible and consisted of 6 days at 4 trials per day (maximum 60 sec each; inter-trial interval, 20-40 min). Probe trials were performed 20 hours after 4, 8, 16, and 24 training trials (10.7- and 11.8-months) or after 4, 8, 12, 16, and 24 training trials (12.0-, 12.5-, and 12.6-months). Probes lasted 60 seconds, but % target quadrant occupancy was calculated using the first 30 seconds because the 129S6FVBF1 mice exhibited extinction. The probe trial following 16 training trials (Day 5 target quadrant occupancy) was determined to be the most sensitive to the effect of transgene on performance across the age range tested. Mice with Day 5 probe scores that were >2SD away from each experimental group mean were excluded as outliers (N=5). We do not have evidence that probe performance following 16 training trials is affected by having received two versus three prior probe trials (non-Tg 10.7-11.8 month and non-Tg 12.0-12.6 month did not have significantly different performance in the probe following 16 training trials). All trials were recorded using a computerized tracking system (HVS Image, Hampton UK or Noldus EthoVision 3.0) and performance measures extracted using Wintrack (Wolfer et al., 2001). To coordinate the timing of the assessment of memory with the transient decline in Aβ*56 levels, we used the age of the mice at the time of this probe trial to measure retention of spatial memory and Aβ*56 levels.

Measurement of APP, APP cleavage products and Aβ oligomers in different brain cell compartments

Details of the fractionation and immunoblot methods have been described previously (Lesne et al., 2006). Briefly, the forebrain was subjected to a 4-step extraction protocol generating four fractions (extracellular-enriched soluble, intracellular-enriched soluble, membrane-enriched and insoluble). 100-250 μg of protein of appropriate fraction was resuspended with 4X Tricine loading buffer and loaded onto pre-cast 10-20% Tris-Tricine gels (Bio-Rad). Proteins were transferred to 0.2 μm nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad). Membranes were boiled for 8 min in PBS and blocked in TBST (Tris-Buffered Saline-Tween®20) containing 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) plus 5% Top-Block (Sigma), and probed with appropriate antisera/antibodies diluted in 5%BSA-5%Top-Block TBST. Blots were developed with an ECL detection system (Supersignal Pico Western system, Pierce).

Determination of the rates of accumulation of SDS-soluble Aβ42 and SDS-insoluble, formic acid-soluble Aβ42

We determined the rate at which SDS-soluble Aβ(x-42) (SDS Aβ42) and SDS-insoluble, formic acid-soluble Aβ(x-42) (FA Aβ42) accumulated in the brains of B6SJL-Tg2576 mice by using previously published levels of SDS Aβ42 and FA Aβ42 (see Figure 3 of Kawarabayashi et al., 2001) to calculate the monthly changes in their levels. The Aβ measurements were performed using sandwich ELISA with 3160 polyclonal capture antibodies and BC05 [Aβ(x-42)] or BA27 [Aβ(x-40)] detection antibodies.

RESULTS

A transient reduction in soluble Aβ oligomers occurs at ~12 months of age

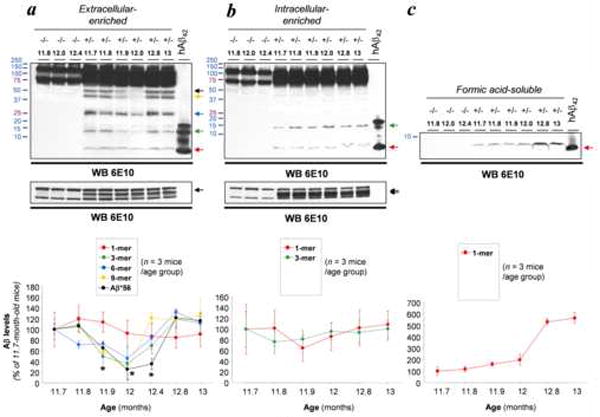

We measured the temporal pattern of expression of soluble Aβ oligomers in the extracellular-enriched fraction at closely spaced intervals between 11.7 and 13 months of age, and found a transient reduction in soluble oligomeric Aβ levels between 11.9 and 12.4 months (Fig. 1a). During this time, loading controls, sAPPα levels, and monomeric Aβ (86.83 ± 24.85% vs. controls, n = 3 per age group) were not significantly changed. Aβ*56 levels (25.65 ± 20.32% vs. controls) and, to a lesser extent, trimeric Aβ levels (36.28 ± 29.45% vs. controls) were markedly reduced at 12.0 months compared to 11.7 month-old Tg2576+/- mice. Interestingly, the levels of all oligomeric Aβ species had returned to their previous levels by 12.8 months (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Reduction in soluble Aβ assemblies does not result from altered Aβ production nor disruption of Aβ fibrillogenesis. (a) Expression patterns of soluble Aβ assemblies in extracellular-enriched fractions from 11.7- to 13-month-old Tg2576 mice. Arrows indicate the respective electrophoretic migration of Aβ*56, 9-mers, 6-mers, 3-mers and Aβ monomers. Lower insert shows equal loading and equivalent sAPPα (arrow) levels. The relative levels of each Aβ species were quantified in three set of independent experiments using 3 animals per age group and are displayed in the histogram (mean ± standard deviation) (an additional set of data from 12.4-month mice, n = 3, are included but not shown in the immunoblot). (b) Expression patterns of soluble Aβ assemblies in intracellular-enriched fractions from 11.7- to 13-month-old Tg2576 mice. Arrows indicate the respective electrophoretic migration of 3-mers (trimers) and Aβ monomers. Lower insert shows equal loading and equivalent sAPPα (N- and N+O-) levels (double arrow). The relative levels of each Aβ species were quantified in three set of independent experiments using 3 animals per age group and are displayed in the histogram (mean ± standard deviation). (c) Fibrillar Aβ levels were determined in formic acid-soluble fractions. Quantitative analyses are shown below the immunoblot (mean ± standard deviation).

Ages are indicated in bold characters; APP genotypes (-/- or +/-) are placed above ages. Freshly resuspended synthetic human Aβ 1-42 peptide was loaded as an internal control on the last lane of each presented western blot. Asterisk, p < 0.01 (ANOVA followed by t test).

To determine whether Aβ production was altered during the same time interval, we evaluated Aβ levels in the intracellular-enriched fractions. We previously showed that only trimers and monomers are detected in this fraction (Lesne et al., 2006). In contrast to the extracellular-enriched fractions, no changes in trimers (86.51 ± 41.53% vs. controls) or monomers (95.92 ± 67.06% vs. controls) were observed (Fig. 1b), indicating that the modulation of extracellular oligomeric Aβ species can not be attributed to fluctuating levels of intracellular Aβ.

Finally, we assayed the amounts of insoluble, fibrillar Aβ in the formic-acid soluble fraction to verify the natural progression of Aβ plaque formation (Fig. 1c). As expected, fibrillar Aβ levels increased substantially between 11.7 and 13 months of age (531.56 ± 23.87% vs. 11.7-month-old Tg2576+/- mice).

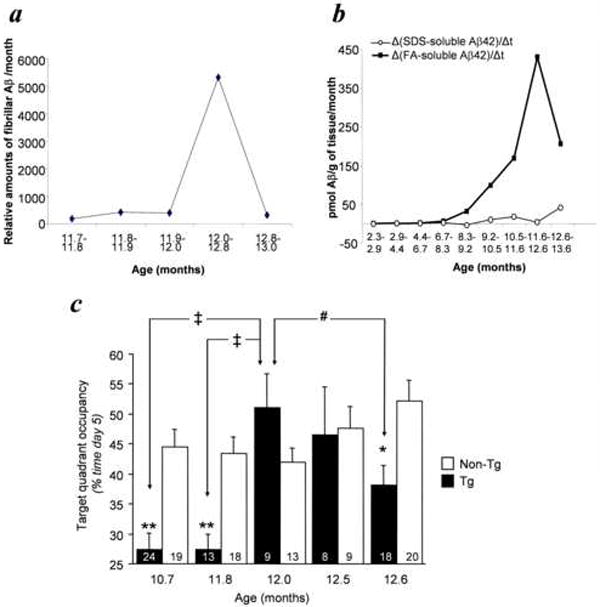

The reduction Aβ oligomers coincides with a rapid rate of fibrillar Aβ accumulation

When the levels of soluble Aβ oligomers were at minimal levels, between 11.9 and 12.4 months of age, the rates of accumulation of insoluble, fibrillar Aβ levels were transiently elevated (Fig. 2a). To confirm the existence of a rapid rate of accumulation of insoluble Aβ at ~12 months in Tg2576 mice, we re-analyzed previously published data from a different set of Tg2576 mice (see Figure 3 in Kawarabayashi et al., 2001). Despite a difference in strain background between the two sets of Tg2576 studied, we nonetheless identified a peak in the rate of accumulation of insoluble Aβ(x-42) occurring between 11.6 and 12.6 months of age, closely overlapping with the results from our current set of Tg2576 mice (Fig. 2b). This peak corresponded to a stagnation point in the rate of accumulation of soluble Aβ(x-42) (Fig. 2b). In Tg2576 mice, compact fibrillar deposits appear at 7-8 months of age and mature amyloid plaques become evident by 12 months (Hsiao et al., 1996; Kawarabayashi et al., 2001). Thus, the observed peak rate of accumulation of fibrillar Aβ occurred at the age at which mature amyloid plaques begin to appear.

Fig. 2.

Recovery of spatial reference memory parallels an increase rate of amyloid deposition. (a) The rate of change of Aβ present in the insoluble, formic-acid extractable fraction, estimated from the data shown in Figure 1c, peaks at 11.9-12.0 months of age. (b) The levels of SDS Aβ(x-42) and FA Aβ(x-42) in a different set of Tg2576 mice were previously published (Figure 3, Kawarabayashi et al., 2001). Using these data, we calculated the monthly rates of change of SDS Aβ(x-42) and FA Aβ(x-42) and found a peak at 11.6-12.6 months of age. (c) Target quadrant occupancy during the probe trial on day 5 of spatial training. Tg2576 mice were impaired at 10.7- and 11.8-months, were not significantly different from non-Tg littermates at 12.0- and 12.5-months, and were impaired at 12.6-months, while non-Tg mice had equivalent performance across all ages (ANOVA, Age x Tg, P<0.01; Tg positive ANOVA, Age, P<0.001; Fisher’s PLSD ‡P<0.001, #P<0.05; t-test, *P<0.01, **P<0.001). Numbers of mice denoted inside bars.

Collectively, the biochemical data indicate that a transient reduction in the levels of extracellular soluble Aβ assemblies occurs at the age when mature amyloid plaques begin to appear, and that this reduction is not due to altered Aβ production.

Lowering of Aβ*56 is associated with memory recovery

Since Aβ*56 appears to impair memory in Tg2576 mice, we predicted that memory dysfunction would be attenuated or even reversed when the levels of Aβ*56 were transiently reduced, between 11.9 and 12.4 months of age, despite an increase in the amyloid plaque load. Therefore, we measured spatial reference memory in five separate groups of Tg2576 mice between the ages of 10.7 and 12.6 months (Fig. 2c). As previously documented (Westerman et al., 2002), the performance of Tg2576 mice at 10.7, 11.8 and 12.6 months was significantly lower than in non-Tg littermates. Remarkably, the performance of the 12.0- and 12.5-month Tg2576 mice, whose ages fell within the interval of reduced Aβ*56, was similar to that of non-Tg littermates.

Thus, the reduction in the levels of Aβ*56 was associated with an interlude of normal memory function. Our observations confirm our earlier report of reversible memory loss in Tg2576 mice following passive immunization with Aβ antibodies (Kotilinek et al., 2002), and support our previous results showing the non-permanent nature of Aβ*56-induced memory deficits (Lesne et al., 2006).

DISCUSSION

Here we show that a transient reduction of Aβ*56 corresponded with the full restoration of spatial reference memory in Tg2576 mice. The data indicate that despite an increasing amount of amyloid plaque in the brain, the reduction or removal of Aβ*56 was associated with improved memory function. Taken together with previous results showing impaired memory in mice lacking amyloid plaques but producing Aβ*56 (Lesne et al., 2006), we conclude that in the early stages of amyloid deposition there is no association between plaques and memory loss, in contrast to a strong association between Aβ*56 and memory loss.

The data suggest that a transient change in the kinetics of plaque formation takes place at ~12 months of age, which drives Aβ toward fibrillar Aβ formation and results in a dramatic reduction in Aβ*56 levels. Although we cannot exclude the alternative possibilities that soluble Aβ assemblies are cleared or degraded during this specific time interval, several reasons make this unlikely: i) the transient reduction in Aβ oligomers is extremely brief (only a few weeks); and ii) Aβ*56 is resistant to harsh conditions ex vivo (i.e. 4% SDS, 10% HFIP) (Lesne et al., 2006). Moreover, although the susceptibility of Aβ*56 to proteolytic catabolism in vivo is unknown, it is unlikely that there is a transient proteolytic process occurring for a few weeks around 12 months of age that degrades oligomers but leaves monomers and plaques intact.

Considerable advances in our understanding of the neuronal effects of naturally derived Aβ oligomers, generated in cultured cells or in brain tissue, have been made in recent years. Although direct comparisons of in vitro- (cell lines, primary cultured neurons) and in vivo- (brain tissues) derived Aβ oligomers have not been done, the current literature suggests that they exert distinct effects. Cells transfected with variant APP genes may produce low-n Aβ oligomers such as Aβ dimers and trimers. These low-n oligomers reduce dendritic spine density in vitro (Shankar et al., 2007), and impair the maintenance, but not the initiation, of LTP (Walsh et al., 2002). Thus, the data on cell-derived Aβ oligomers suggest that they are synaptotoxic.

In contrast, several lines of evidence indicate that brain-derived low-n oligomers such as Aβ trimers in Tg2576 mice are not synaptotoxic. First, Tg2576 animals produce a constant level of Aβ trimers throughout life (Lesne et al., 2006), but mice younger than ~10 months of age, prior to the formation of mature amyloid plaques, show no synaptic alterations (Spires et al., 2005). However, synaptotoxicity is evident in older, plaque-bearing Tg2576 mice, with reductions in dendritic spine density occurring within a 100-micron halo surrounding the surface of plaques (Spires et al., 2005). Second, evoked synaptic responses in 8 to 10 month-old Tg2576 mice are normal, but become abnormal at 14 months, an age when plaque deposition is substantial (Stern et al., 2004). Third, the levels of Aβ trimers in 6 month-old Tg2576 mice do not correlate with memory dysfunction (Lesne et al., 2006). These lines of evidence strongly argue against a synaptotoxic effect of the soluble Aβ trimers we measured in Tg2576 mice. Moreover, they lessen the possibility that in the current study the improvement in memory function in ~12-month Tg2576 mice was due to the lowering of the Aβ trimers that were reduced along with Aβ*56.

The published studies of naturally produced Aβ oligomers indicate that there may be two distinct forms of low-n Aβ oligomers in the Tg2576 brain. Clearly, there are non-synaptotoxic Aβ trimers that are not intimately associated with amyloid plaques. Still unclear is the nature of the synaptotoxic Aβ species, or other agents, located within the 100-micron wide halo surrounding the amyloid plaques. However, they could potentially resemble cell-derived low-n Aβ oligomers, given their identical damaging effects on dendritic spines.

Tg2576 mice lack neurodegeneration (Irizarry et al., 1997), and may therefore be a model of early or pre-clinical AD (Ashe, 2001, Lesne et al., 2006). Our results suggest that strategies aimed at reducing Aβ*56 could be an effective approach for treating patients suffering from early AD-related memory problems. Conversely, strategies that reduce amyloid burden without concomitantly decreasing Aβ*56 are less likely to be effective.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ashe KH. Learning and memory in transgenic mice modeling Alzheimer’s disease. Learn Mem. 2001;8:301–308. doi: 10.1101/lm.43701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings BJ, Pike CJ, et al. Beta-amyloid deposition and other measures of neuropathology predict cognitive status in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1996;17:921–933. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(96)00170-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsia AY, Masliah E, et al. Plaque-independent disruption of neural circuits in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:3228–3233. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.3228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao K, Chapman P, et al. Correlative memory deficits, Aß elevation, and amyloid plaques in transgenic mice. Science. 1996;274:99–102. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5284.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irizarry MC, McNamara M, et al. APPSw transgenic mice develop age-related A beta deposits and neuropil abnormalities, but no neuronal loss in CA1. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1997;56:965–973. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199709000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawarabayashi T, Younkin LH, et al. Age-dependent changes in brain, CSF, and plasma amyloid ß protein in the Tg2576 transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;21:372–381. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-02-00372.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayed R, Head E, et al. Common structure of soluble amyloid oligomers implies common mechanism of pathogenesis. Science. 2003;300:486–489. doi: 10.1126/science.1079469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein WL, Krafft GA, et al. Targeting small Abeta oligomers: the solution to an Alzheimer’s disease conundrum? Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:219–224. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01749-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles RB, Wyart C, et al. Plaque-induced neurite abnormalities: implications for disruption of neural networks in Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:5274–5279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.5274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotilinek LA, Bacskai B, et al. Reversible memory loss in a mouse transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6331–6335. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06331.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert MP, Barlow AK, et al. Diffusible, nonfibrillar ligands derived from Abeta1-42 are potent central nervous system neurotoxins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:6448–6453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesne S, Koh MT, et al. A specific amyloid-beta protein assembly in the brain impairs memory. Nature. 2006;440:352–357. doi: 10.1038/nature04533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mucke L, Masliah E, et al. High-level neuronal expression of abeta 1-42 in wild-type human amyloid protein precursor transgenic mice: synaptotoxicity without plaque formation. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4050–4058. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-04050.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar GM, Bloodgood BL, et al. Natural oligomers of the Alzheimer amyloid-beta protein induce reversible synapse loss by modulating an NMDA-type glutamate receptor-dependent signaling pathway. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2866–2875. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4970-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spires TL, Meyer-Luehmann M, et al. Dendritic spine abnormalities in amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice demonstrated by gene transfer and intravital multiphoton microscopy. J Neurosci. 2005;25:7278–7287. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1879-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern EA, Bacskai BJ, et al. Cortical synaptic integration in vivo is disrupted by amyloid-beta plaques. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4535–4540. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0462-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbanc B, Cruz L, et al. Neurotoxic effects of thioflavin S-positive amyloid deposits in transgenic mice and Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13990–13995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222433299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh DM, Klyubin I, et al. Naturally secreted oligomers of amyloid beta protein potently inhibit hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo. Nature. 2002;416:535–539. doi: 10.1038/416535a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerman MA, Cooper-Blacketer D, et al. The relationship between Abeta and memory in the Tg2576 mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2002;22:1858–1867. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-05-01858.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfer DP, Madani R, et al. Extended analysis of path data from mutant mice using the public domain software Wintrack. Physiol Behav. 2001;73:745–753. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(01)00531-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]