Neuromyelitis optica (NMO) is an inflammatory and demyelinating disease characterized by recurrent attacks of optic neuritis (ON) and longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis (LETM).1 NMO is associated with antibodies against the aquaporin-4 (AQP4) water channel.2 NMO–immunoglobulin G (IgG) predicts a relapsing course and is a supportive criterion for NMO.3–5 The high risk of relapse, sometimes with devastating effects, makes early diagnosis important. Early identification permits counseling and consideration for immunosuppressive therapy. The serum NMO-IgG assay, using indirect immunofluorescence, is 73% sensitive and 91% specific for clinically defined NMO.6 While helpful when positive, the sensitivity is insufficient to exclude the diagnosis. We describe 3 of 26 patients with NMO at our institution with NMO-IgG positivity restricted to CSF.

Case reports.

Case 1.

A 25-year-old African American woman presented with leg numbness and mild tetraparesis that resolved over 1 month. Two months later, she developed a midthoracic sensory level, again with recovery. The next month, bilateral leg weakness impaired her ability to ambulate. MRI (figure, A–C) demonstrated T2 hyperintensities (T2H) and patchy enhancement spanning the medulla through C7 and T2–T11. Brain MRI revealed a single nonspecific T2H. Visual evoked potentials (VEPs) were normal. Serum NMO-IgG was negative but CSF NMO-IgG was positive. IgG index was elevated to 0.79, CSF leukocytes were 24/μL, but albumin index, IgG synthesis, and oligoclonal bands (OCBs) were normal. Serum antinuclear antibodies (ANA) were negative. Treatment included IV glucocorticoids and rituximab with no further exacerbations. After 8 months of disease, Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) was 6.0.

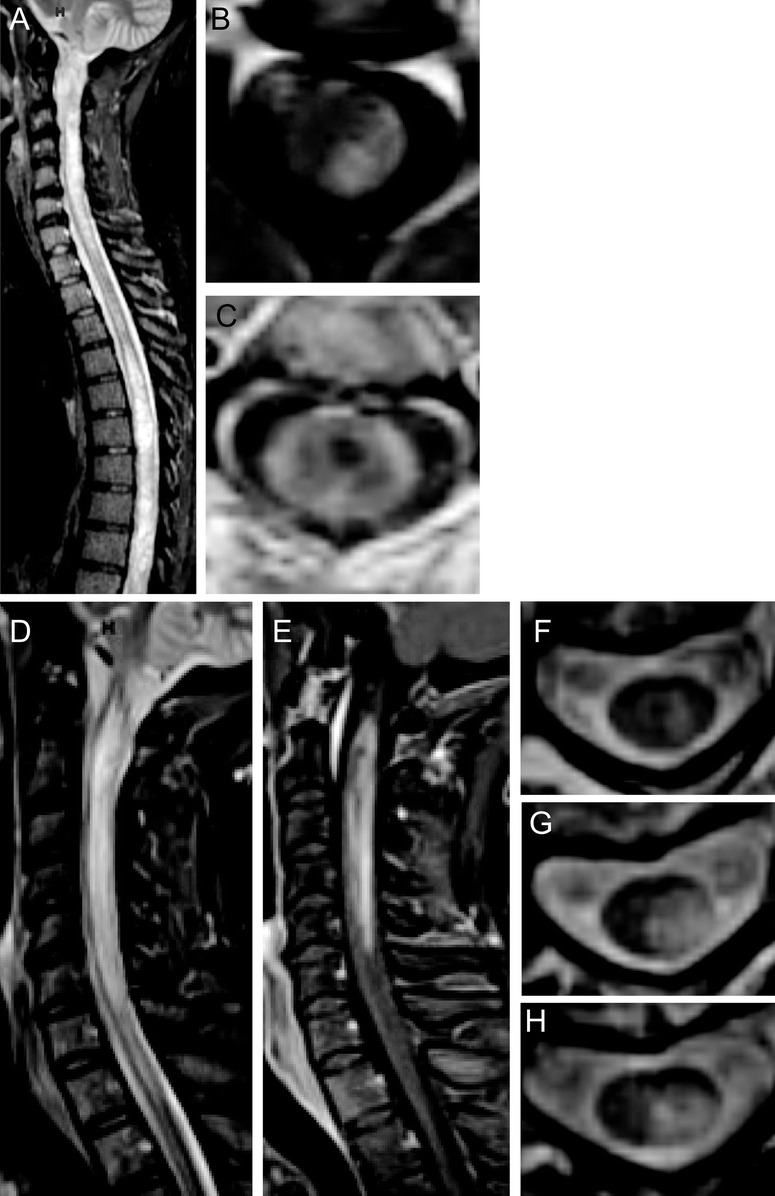

Figure Neuroimaging of CSF antibody-positive neuromyelitis optica

Case 1: Sagittal T2-weighted STIR MRI (A) shows hyperintensity throughout the cervical and thoracic spinal cord. Axial T1-weighted postgadolinium MRI at the level C2 (B) shows dorsal enhancement and at level C2–3 (C) shows peripheral enhancement and a central T1-weighted hypointensity. Case 2: Sagittal T2-weighted STIR MRI (D) shows hyperintensity from the lower medulla caudally with enhancement on T1-weighted postgadolinium MRI (E). Case 3: Axial T2-weighted MRI at successive levels C2 (F), C3 (G), and C4 (H) show central gray matter involvement.

Case 2.

A 43 year-old African American woman presented with right-sided weakness and numbness. MRI demonstrated longitudinally extensive T2H with enhancement from the lower medulla through C6. Brain MRI was nondiagnostic. Serum NMO-IgG was negative. She recovered after IV glucocorticoids. Four months later, she developed right-sided weakness, left-sided numbness, and difficulty ambulating. Cervical spine MRI (figure, D and E) showed increased T2H with enhancement. VEPs were normal. Repeat serum NMO-IgG was negative. CSF NMO-IgG was positive with 1:8 titer. CSF IgG index was 0.76, IgG synthesis rate was 6.5, with 6 leukocytes/μL. OCBs and albumin index were normal. Serum ANA was negative. Treatment has included monthly IV glucocorticoids with no exacerbations. EDSS after 5 months of disease was 2.0.

Case 3.

A 49-year-old white woman presented with left upper extremity paresthesias and clumsiness. This improved, but was followed 2 months later by ascending bilateral numbness and weakness requiring a walker. MRI (figure, F–H) demonstrated enhancing expansile T2 hyperintensity spanning C2–C5. Brain MRI and VEPs were normal. She improved with IV glucocorticoids. NMO-IgG was negative in serum, but positive in CSF. Other CSF parameters were normal. Serum ANA was 1:320. Azathioprine was started, with no further exacerbations. After 2 years of disease, EDSS was 2.0.

Discussion.

We report three cases of NMO spectrum disorder with restriction of NMO-IgG positivity to the CSF. The cases presented with rapidly relapsing LETM, and a normal or nondiagnostic brain MRI. While none showed evidence for ON, these individuals have been followed less than 2 years. In each case, the second relapse was severe and disabling, occurring within months of onset. In each patient, serum NMO-IgG testing was negative at a 1:120 dilution and simultaneous CSF NMO-IgG was positive during an exacerbation, before administration of corticosteroids. Antibody testing was performed by the same laboratory (Mayo Medical Laboratories). The cause of NMO-IgG seronegativity in these three CSF-positive patients is unknown. The presence of a coexisting, interfering antibody may hinder serologic interpretation. However, only case 3 was noted to have coexisting ANA. The CSF albumin indices indicated intact blood–brain barriers.

Serum testing for NMO-IgG remains the standard test for confirming a diagnosis of relapsing NMO spectrum disorder. In our three seronegative cases of relapsing LETM, detection of NMO-IgG in the CSF confirmed the diagnosis of an NMO spectrum disorder, and mandated initiation of immunosuppressive therapies. The potential value of early treatment emphasizes the importance of making the correct diagnosis.7 If NMO is strongly suspected and serum NMO-IgG is negative, measurement of CSF NMO-IgG is recommended and may add to the overall sensitivity of laboratory testing. Clinical scenarios that may warrant supplementary testing of CSF include the following: 1) LETM, 2) relapsing TM, 3) severe and bilateral ON, 4) ON with poor recovery, and 5) rapidly relapsing ON.

CSF studies should not be a substitute for serum testing. Larger systematic studies are required to determine the sensitivity and specificity of combined serum and CSF testing. Whether distinct clinical characteristics exist for cases with CSF restricted NMO-IgG positivity remains to be determined.

Supported by grant UL1 RR024992 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the NIH and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. NIH funding included UL1RR024992 (E.C.K.), K23NS052430-01A1 (R.T.N.), K12RR02324902 (R.T.N.), K24 RR017100 (A.H.C.), CA1012 (A.H.C.); American Academy of Neurology Foundation Clinical Research Training Fellowship (E.C.K.); and National MS Society FG1782A1 (J.X.). Dr. Cross was supported in part by the Manny and Rosalyn Rosenthal–Dr. John L. Trotter Chair in Neuroimmunology.

Disclosure: Drs. Klawiter, Alvarez, Xu, Paciorkowski, and Zhu have no disclosures to report. Dr. Parks is a participant in clinical trials for BioMS and Teva Neurosciences. She has received consulting fees or speaking honoraria from Biogen Idec, Bayer Healthcare, Teva Neurosciences, and Pfizer/Serono. Dr. Cross has received research funding, clinical trial funding, honoraria, or consulting fees from the NIH, National MS Society USA, Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers, Genentech, Inc., Berlex (now Bayer Healthcare), Biogen-Idec, Teva Neuroscience, Acorda Therapeutics, Serono, Pfizer, and BioMS. Dr. Naismith is a participant in clinical trials for Fampridine SR by Acorda Therapeutics. He has received consulting fees and speaking honoraria from Bayer Healthcare, Biogen Idec, and Teva Neurosciences. Research funding is through the NIH and National MS Society.

The corresponding author takes full responsibility for the data, the analyses and interpretation, and the conduct of the research. The corresponding author has full access to all the data and has the right to publish any and all data, separate and apart from the attitudes of the sponsor. The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR or NIH.

Received September 29, 2008. Accepted in final form November 25, 2008.

Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Eric Klawiter, Neurology, Box 8111, 660 S. Euclid Ave., Washington University, St. Louis, MO 63110; klawitere@neuro.wustl.edu

REFERENCES

- 1.Wingerchuk DM, Lennon VA, Lucchinetti CF, Pittock SJ, Weinshenker BG. The spectrum of neuromyelitis optica. Lancet Neurol 2007;6:805–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lennon VA, Kryzer TJ, Pittock SJ, Verkman AS, Hinson SR. IgG marker of optic-spinal multiple sclerosis binds to the aquaporin-4 water channel. J Exp Med 2005;202:473–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weinshenker BG, Wingerchuk DM, Vukusic S, et al. Neuromyelitis optica IgG predicts relapse after longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis. Ann Neurol 2006;59:566–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matiello M, Lennon VA, Jacob A, et al. NMO-IgG predicts the outcome of recurrent optic neuritis. Neurology 2008;70:2197–2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wingerchuk DM, Lennon VA, Pittock SJ, Lucchinetti CF, Weinshenker BG. Revised diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica. Neurology 2006;66:1485–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lennon VA, Wingerchuk DM, Kryzer TJ, et al. A serum autoantibody marker of neuromyelitis optica: distinction from multiple sclerosis. Lancet 2004;364:2106–2112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cree BA, Lamb S, Morgan K, Chen A, Waubant E, Genain C. An open label study of the effects of rituximab in neuromyelitis optica. Neurology 2005;64:1270–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]