Abstract

Background:

Amyloid-beta protein (Aβ) plays a key role in Alzheimer disease (AD) and is also implicated in cerebral small vessel disease. Serum total homocysteine (tHcy) is a risk factor for small vessel disease and cognitive impairment and correlates with plasma Aβ levels. To determine whether this association results from a common pathophysiologic mechanism, we investigated whether vitamin supplementation–induced reduction of tHcy influences plasma Aβ levels in the Vitamin Intervention in Stroke Prevention (VISP) study.

Methods:

Two groups of 150 patients treated with either the high-dose or low-dose formulation of pyridoxine, cobalamin, and folic acid in a randomized, double-blind fashion were selected among the participants in the VISP study without recurrent stroke during follow-up and in the highest 10% of the distribution for baseline tHcy levels. Concentrations of plasma Aβ with 40 (Aβ40) and 42 (Aβ42) amino acids were measured at baseline and at the 2-year visit.

Results:

tHcy levels significantly decreased with vitamin supplementation in both groups. tHcy were strongly correlated with Aβ40 but not Aβ42 concentrations. There was no difference in the change in Aβ40, Aβ42 (p = 0.40, p = 0.35), or the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio over time (p = 0.86) between treatment groups. Aβ measures were not associated with cognitive change.

Conclusions:

This double-blind randomized controlled trial of vitamin therapy demonstrates a strong correlation between serum tHcy and plasma Aβ40 concentrations in subjects with ischemic stroke. Treatment with high dose vitamins does not, however, influence plasma levels of Aβ, despite their effect on lowering tHcy. Our results suggest that although tHcy is associated with plasma Aβ40, they may be regulated by independent mechanisms.

GLOSSARY

- Aβ

= amyloid-beta;

- AD

= Alzheimer disease;

- BMI

= body mass index;

- DBP

= diastolic blood pressure;

- MMSE

= Mini-Mental State Examination;

- mRS

= modified Rankin Scale;

- NIHSS

= NIH Stroke Scale;

- SBP

= systolic blood pressure;

- tHcy

= total homocysteine;

- VISP

= Vitamin Intervention in Stroke Prevention study.

Amyloid β-protein (Aβ40, Aβ42) deposition in the brain is a hallmark of Alzheimer disease (AD) and is thought to be the cause of cognitive impairment and dementia.1 Reduction of Aβ production is a candidate approach for treatment and prevention of cognitive impairment and dementia.2 Plasma total homocysteine (tHcy) levels are correlated with plasma Aβ, although the biologic importance of this association is uncertain.3–5 Plasma tHcy has been implicated as a risk factor for small vessel cerebrovascular disease and the development of cognitive impairment and dementia.6–8

There are several potential implications of these associations in relation to AD, cognitive impairment, and microangiopathy. tHcy may increase the risk of AD by elevating Aβ levels. Alternatively, Aβ may increase the risk of microangiopathic changes through elevation of tHcy levels. Neurotoxicity may be potentiated by the dual elevation of both tHcy and Aβ. Finally, tHcy and Aβ may be markers of a pathogenic mechanism and independent of each other.

Since plasma tHcy levels are readily modifiable by high-dose vitamin supplementation, we hypothesized that plasma Aβ levels may also be modifiable by vitamin supplementation. We thus aimed to test whether this association results from a common pathophysiologic mechanism between these biomarkers or if in fact they represent independent processes.

The Vitamin Intervention in Stroke Prevention (VISP) was a randomized controlled trial designed to test the hypothesis that lowering tHcy levels with large doses of folic acid, pyridoxine, and vitamin B12 would reduce the incidence of recurrent stroke or myocardial infarction.9 Although the study did not show a benefit for the primary endpoint, tHcy was successfully lowered with vitamin therapy. We investigated plasma Aβ as an add-on component to the VISP study to test the hypotheses whether vitamin supplementation–induced reduction of tHcy over 2 years influences plasma Aβ levels.

METHODS

Subjects.

Details of the VISP trial have been published previously.9 Briefly, the VISP trial enrolled a total of 3,680 adults who 1) were within 120 days of a mild or moderate ischemic stroke (modified Rankin Scale [mRS] score of ≤ 3); 2) were 35 years or older; and 3) had a fasting tHcy level approximately greater than the 25th percentile for patients with stroke. Subjects were enrolled between September 1996 and December 2001 at 56 centers in the United States, Canada, and Scotland, and randomized to receive a high dose formulation (n = 1,827) containing 25 mg of pyridoxine, 0.4 mg of cobalamin (B12), and 2.5 mg of folic acid or the low dose formulation (n = 1,853) of 200 mcg of pyridoxine, 6 mcg of cobalamin, and 20 mcg of folic acid.

Baseline VISP data included a standardized medical history, demographic variables, body mass index (BMI), stroke symptoms questionnaire, systolic and diastolic blood pressures, and a neurologic examination. Several scales which measure disability and cognition were administered to all patients (mRS, NIH Stroke Scale [NIHSS], Mini-Mental State Examination [MMSE]),9 and serum levels of folate, B12 levels, and a lipid profile were ascertained. tHcy levels were obtained while fasting and after methionine loading.9

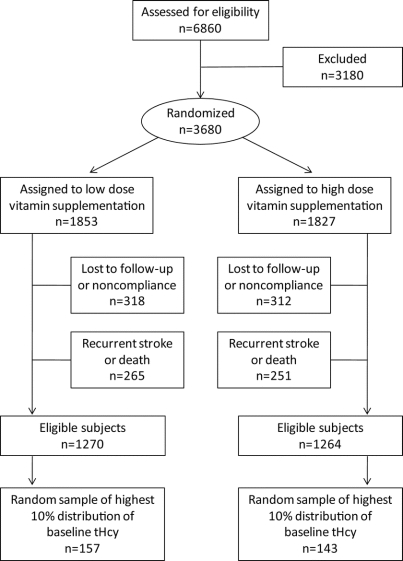

The assembly of the cohort for this substudy is shown in the figure. We selected at random a group of 150 patients treated with high dose formulation and another group of 150 patients with low dose formulation (within sex and 10-year age strata) among participants who did not have a recurrent stroke during the trial and who were in the highest 10% of the distribution for baseline tHcy levels, in order to maximize potential observed treatment effect. The sample numbers were selected based on power analysis and practical capacity for performing the outcome measures. In the current study, we had 85% power to detect an absolute difference of 7.5% in Aβ levels with high dose vitamin supplementation. Requirements for inclusion in the pool of potential subjects were availability of the following at both baseline and 2-year visits: blood samples, vitamin and tHcy levels, and MMSE. Individuals with less than 75% compliance by pill count were excluded. Plasma Aβ levels were measured in blood samples drawn at baseline and at the 2-year visit. This study was performed with approval by the ethics committees of all study institutions and administrative sites. Written informed consent was obtained from every potential participant. This substudy was performed with approval and in accord with the guidelines of our institutional review boards.

Figure Assembly of study sample from the Vitamin Intervention in Stroke Prevention (VISP) cohort

Recruitment for the VISP cohort is described in detail elsewhere.9 Briefly, patients with a presumptive diagnosis of acute ischemic stroke were screened. Patients with total homocysteine levels (tHcy) that exceeded defined thresholds were randomized for treatment with high- or low-dose vitamin therapy. A random sample of eligible subjects with the highest 10% of tHcy were included in the study.

Blood collection.

Blood was collected in polypropylene sterile plunger tubes containing potassium ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid. Samples were centrifuged at 1,380 g for 15 minutes, aliquoted with a protease inhibitor cocktail and frozen in dry ice, and stored at −80°C.

Biochemical assays.

Plasma tHcy was determined by high-performance liquid chromatography, as detailed in our previous studies.9–11 Plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 concentrations were determined by sandwich ELISA using the BNT77 capture antibody and C-terminal specific detector antibodies BA27 and BC05 as previously described and validated.4,12 We have demonstrated this ELISA system to detect Aβ40 or Aβ42 at concentrations as low as 1 pmol/L and to detect both free and protein-bound Aβ.4,12 All biochemical analyses were performed without knowledge of subjects’ clinical or radiographic information.

Statistical analyses.

For univariate analysis, χ2 tests were used to compare two categorical variables and analyses of variance were performed to compare continuous variables distributions across groups. All p values were two-tailed and criterion for significance was p < 0.05.

To determine whether vitamin treatment affected plasma Aβ levels, we adopted a linear mixed effects model for the data longitudinally measured over the 2-year period.13 This technique allows for analysis of time-independent and time-dependent variables to identify associations with these variables as well as their trajectories over time. The parameter estimates indicate how much change in plasma Aβ levels resulted from a one unit change in each risk factor. Analyses were also performed using the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio, as it has been recently demonstrated that this ratio may be associated with an increased risk of dementia.14,15 For all models of the three outcome measures (Aβ40, Aβ42, and Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio), we investigated the effects of age, gender, clinical, and laboratory variables on change in plasma Aβ levels. Covariates that were associated with clinical scales in univariate analysis (p < 0.10) were considered in the final model.

RESULTS

The baseline clinical and demographic variables are presented in table 1. There were no significant differences in clinical or demographic variables between the two groups. There were no differences between Aβ40 or Aβ42 levels between treatment groups at baseline (p = 0.97 and 0.30, respectively). The median follow-up interval was 24.0 months.

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of subjects in cohort according to high or low vitamin treatment group

Levels of tHcy at 2-year follow-up declined in both treatment groups (change in tHcy at 2 years 4.73 ± 8.98 in high treatment group and 1.66 ± 7.79 in the low treatment group; p < 0.0001 and p = 0.009, respectively). Reduction of tHcy was significantly greater in the high treatment group [β (time × treatment group) = −0.1289; p < 0.0001]. Baseline tHcy levels and tHcy levels at 2-year follow-up were significantly correlated with Aβ40 levels (r = 0.25 and 0.29, respectively; p < 0.0001 for both comparisons). However, tHcy levels were not correlated with Aβ42 levels at baseline (p = 0.50) or at 2-year follow-up (p = 0.20).

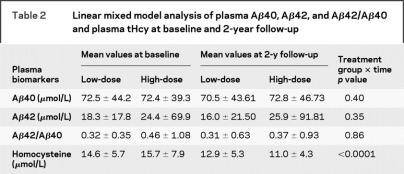

Levels of Aβ40, Aβ42, and the Aβ42-Aβ40 ratio at baseline and follow-up are shown in table 2. Aβ40 levels did not significantly change over the treatment period (β = −0.09, p = 0.44) and there was no significant difference in the change in Aβ40 levels between treatment groups (β = 0.14, p = 0.40). Similarly, there was no significant change in either Aβ42 levels or the Aβ42-Aβ40 ratio over time between treatment groups (p = 0.35 and p = 0.86) (table 2).

Table 2 Linear mixed model analysis of plasma Aβ40, Aβ42, and Aβ42/Aβ40 and plasma tHcy at baseline and 2-year follow-up

There was no association between Aβ40, Aβ42 levels, or the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio with MMSE at baseline (p = 0.10, p = 0.62, and p = 0.85, respectively) or follow-up (p = 0.28, p = 0.74, and p = 0.50, respectively). Aβ levels did not influence change in MMSE over the treatment period.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we sought to define the relationship between plasma Aβ levels and homocysteine lowering in a cohort of subjects from the randomized controlled VISP trial.9 The current study demonstrates a strong association between tHcy and plasma Aβ40 levels in subjects with ischemic stroke in this longitudinal analysis. These findings confirm and extend cross-sectional observational studies which have previously reported this association.3–5 However, despite the association of tHcy levels with Aβ40, Aβ40 levels were not influenced by vitamin treatment.

The strength of this study stems from the fact that subjects had randomized assignment to treatment type and that these subjects were followed prospectively for recurrent stroke and other cardiovascular events over a 2-year period with complete follow-up of all patients.

Elevated tHcy is a predictive factor for vascular disease, including ischemic heart disease and stroke.16 Several studies have suggested that elevated tHcy is also a risk factor for white matter disease,17 cognitive impairment,17–20 and AD.6–8 These associations may be explained by vascular21 or direct neurotoxic22,23 effects of tHcy.

Elevated plasma concentrations of Aβ are associated with microvascular disease in both population- based epidemiologic studies and cohorts of subjects with cognitive impairment.4,24,25 In vitro studies have suggested direct physiologic or toxic effects of Aβ on the contractile/relaxation elements of the blood vessel wall.26–28 Data regarding plasma Aβ and the risk of cognitive decline are conflicting. Cohort studies have reported that elevated plasma Aβ40 or Aβ42 levels increase the risk of developing AD over 5–8 years,14,15,29 although a fourth found that plasma Aβ42 levels were not associated with cognitive decline over 30 months.30 Other studies have found low Aβ40 or Aβ42 levels associated with incident AD14,15 or more rapid cognitive decline in AD subjects.31 Finally, some have suggested that low concentrations of plasma Aβ42 in combination with increased concentrations of plasma Aβ40 are associated with an increased risk of cognitive impairment and dementia.14,15

This study did not find a significant treatment effect of high dose vitamins on plasma levels of Aβ40 despite the effect of the high dose vitamins on lowering tHcy. This suggests that although tHcy is associated with plasma Aβ40, they may have independent pathophysiologic mechanisms. This is in contrast to Flicker et al.,33 who detected an effect of tHcy lowering on plasma Aβ40. These differences may be reflective of the patient population (stroke patients with high tHcy in the VISP study, community dwelling older men in the study by Flicker et al.), confounding by dietary changes in folate consumption (VISP study), or differences in the form of Aβ measured by the assays (the assay used in this study measures protein bound Aβ, and does not detect oligomeric forms). Additionally, given the definition of the subcohort as those VISP subjects in the highest quintile of tHcy at baseline, a component of the reduction of tHcy may represent regression to the mean rather than vitamin effects.

The VISP study results may suggest that tHcy is merely a marker for vascular disease and risk of cognitive decline because tHcy lowering does not influence Aβ40 levels.9 Although tHcy is associated with plasma Aβ40, high dose vitamin treatment may differentially impact these two plasma markers.4 Finally, correlations between tHcy and other metabolites of the methylation cycle, such as S-adenosylhomocysteine, have been reported.34 How these metabolites respond to vitamin treatment remains to be elucidated. Further epidemiologic and therapeutic studies investigating the relationship between cerebrovascular disease and these potentially important plasma biomarkers (tHcy and Aβ40, Aβ42) are needed.

Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Anand Viswanathan, Hemorrhagic Stroke Research Program, Massachusetts General Hospital Stroke Research Center, 175 Cambridge Street, Suite 300, Boston, MA 02114 aviswanathan1@partners.org

Supported by NIH grants 5K23NS046327-04, P50AG05134, and 5R01AG026484-02 (Massachusetts General Hospital), the Harvard Center for Neurodegeneration and Repair, and NIH grant 5T32NS048005-05 (Harvard School of Public Health).

Disclosure: Michael Irizarry is a stock and options-holding employee of GlaxoSmithKline. No pharmaceutical funding was used in this study.

Received July 3, 2008. Accepted in final form October 8, 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Selkoe DJ. Normal and abnormal biology of the beta-amyloid precursor protein. Annu Rev Neurosci 1994;17:489–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greenberg SM, Bacskai BJ, Hyman BT. Alzheimer disease’s double-edged vaccine. Nat Med 2003;9:389–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Irizarry MC, Gurol ME, Raju S, et al. Association of homocysteine with plasma amyloid beta protein in aging and neurodegenerative disease. Neurology 2005;65:1402–1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gurol ME, Irizarry MC, Smith EE, et al. Plasma beta-amyloid and white matter lesions in AD, MCI, and cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Neurology 2006;66:23–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flicker L, Martins RN, Thomas J, et al. Homocysteine, Alzheimer genes and proteins, and measures of cognition and depression in older men. J Alzheimer Dis 2004;6:329–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clarke R, Smith AD, Jobst KA, Refsum H, Sutton L, Ueland PM. Folate, vitamin B12, and serum total homocysteine levels in confirmed Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 1998;55:1449–1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCaddon A, Hudson P, Davies G, Hughes A, Williams JH, Wilkinson C. Homocysteine and cognitive decline in healthy elderly. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2001;12:309–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seshadri S, Beiser A, Selhub J, et al. Plasma homocysteine as a risk factor for dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med 2002;346:476–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Toole JF, Malinow MR, Chambless LE, et al. Lowering homocysteine in patients with ischemic stroke to prevent recurrent stroke, myocardial infarction, and death: the Vitamin Intervention for Stroke Prevention (VISP) randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004;291:565–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smolin LA, Schneider JA. Measurement of total plasma cysteamine using high-performance liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection. Anal Biochem 1988;168:374–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malinow MR, Kang SS, Taylor LM, et al. Prevalence of hyperhomocyst(e)inemia in patients with peripheral arterial occlusive disease. Circulation 1989;79:1180–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fukumoto H, Tennis M, Locascio JJ, Hyman BT, Growdon JH, Irizarry MC. Age but not diagnosis is the main predictor of plasma amyloid beta-protein levels. Arch Neurol 2003;60:958–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fitzmaurice G, Laird NM, Ware JH. Applied Longitudinal Analysis. New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graff-Radford NR, Crook JE, Lucas J, et al. Association of low plasma Abeta42/Abeta40 ratios with increased imminent risk for mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 2007;64:354–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Oijen M, Hofman A, Soares HD, Koudstaal PJ, Breteler MM. Plasma Abeta(1-40) and Abeta(1-42) and the risk of dementia: a prospective case-cohort study. Lancet Neurol 2006;5:655–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Homocysteine and risk of ischemic heart disease and stroke: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2002;288:2015–2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dufouil C, Alperovitch A, Ducros V, Tzourio C. Homocysteine, white matter hyperintensities, and cognition in healthy elderly people. Ann Neurol 2003;53:214–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lehmann M, Gottfries CG, Regland B. Identification of cognitive impairment in the elderly: homocysteine is an early marker. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 1999;10:12–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morris MS, Jacques PF, Rosenberg IH, Selhub J. Hyperhomocysteinemia associated with poor recall in the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Clin Nutr 2001;73:927–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller JW, Green R, Ramos MI, et al. Homocysteine and cognitive function in the Sacramento Area Latino Study on Aging. Am J Clin Nutr 2003;78:441–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Faraci FM, Lentz SR. Hyperhomocysteinemia, oxidative stress, and cerebral vascular dysfunction. Stroke 2004;35:345–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kruman Kumaravel TS II, Lohani A, Pedersen WA, et al. Folic acid deficiency and homocysteine impair DNA repair in hippocampal neurons and sensitize them to amyloid toxicity in experimental models of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci 2002;22:1752–1762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Obeid R, Herrmann W. Mechanisms of homocysteine neurotoxicity in neurodegenerative diseases with special reference to dementia. FEBS Lett 2006;580:2994–3005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Dijk EJ, Prins ND, Vermeer SE, et al. Plasma amyloid beta, apolipoprotein E, lacunar infarcts, and white matter lesions. Ann Neurol 2004;55:570–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Dijk EJ, Prins ND, Hofman A, van Duijn CM, Koudstaal PJ, Breteler MM. Plasma beta amyloid and impaired CO2-induced cerebral vasomotor reactivity. Neurobiol Aging 2007;28:707–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Niwa K, Younkin L, Ebeling C, et al. Abeta 1-40-related reduction in functional hyperemia in mouse neocortex during somatosensory activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000;97:9735–9740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Niwa K, Carlson GA, Iadecola C. Exogenous A beta1-40 reproduces cerebrovascular alterations resulting from amyloid precursor protein overexpression in mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2000;20:1659–1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thomas T, Thomas G, McLendon C, Sutton T, Mullan M. beta-Amyloid-mediated vasoactivity and vascular endothelial damage. Nature 1996;380:168–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mayeux R, Honig LS, Tang MX, et al. Plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 and Alzheimer’s disease: relation to age, mortality, and risk. Neurology 2003;61:1185–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blasko I, Lederer W, Oberbauer H, et al. Measurement of thirteen biological markers in CSF of patients with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2006;21:9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sundelof J, Giedraitis V, Irizarry MC, et al. Plasma beta amyloid and the risk of Alzheimer disease and dementia in elderly men: a prospective, population-based cohort study. Arch Neurol 2008;65:256–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Locascio JJ, Fukumoto H, Yap L, et al. Plasma amyloid beta-protein and C-reactive protein in relation to the rate of progression of Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 2008;65:776–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Flicker L, Martins RN, Thomas J, et al. B-vitamins reduce plasma levels of beta amyloid. Neurobiol Aging 2008;29:303–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Obeid R, Kasoha M, Knapp JP, et al. Folate and methylation status in relation to phosphorylated tau protein(181P) and beta-amyloid(1-42) in cerebrospinal fluid. Clin Chem 2007;53:1129–1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]