Abstract

Outsider Art (art brut) is defined as a mode of original artistic expression which thrives on its independence, shunning the public sphere and the art market. Such art can be highly idiosyncratic and secretive, and reflects the individual creator's attempt to construct a coherent, albeit strange, private world. Certain practitioners of what may be termed autistic art are examined in the light of this definition; their work is considered as evidence not of a medical condition but of an expressive intentionality entirely worthy of the interest of those drawn to the aesthetic experience.

Keywords: Outsider Art, art brut, autistic art, strangeness, intentionality, private world

1. Defining Outsider Art

It so happens that certain practitioners of what has become known as Outsider Art have occasionally been referred to as ‘autistic’. Applied loosely by non-medical commentators, the term reflects an attempt to identify a certain quality of secretiveness about the artist's manner and his or her seeming reluctance to communicate in a direct fashion. This non-specialist use of a key clinical concept may seem inappropriate to those concerned to explain the condition of autism proper. Nonetheless, it does raise the possibility of a congruity between two separate spheres of creativity, one which I feel to be worth investigating.

Let me first explain my own technical term. ‘Outsider Art’ constitutes an internationally recognized category of self-taught art. Its ambit of use rests on the notion that art making is a widespread human activity reaching far beyond the world of public galleries, teaching institutions and culturally marked art production. Yet it would be wrong to suppose that the term means nothing more than casual doodling or amateurish fumbling. Instead, it refers confidently to an actual fund of original work produced by untutored creators of talent whose expressions convey a strong sense of individuality.

I am in part responsible for launching the concept of Outsider Art in so far as the coinage appeared some years ago as the title of my book (Cardinal 1972). Recent surveys of this field include Peiry (1997), Rhodes (2000a) and Danchin (2006). In fact, Outsider Art had been conceived strictly as a study of art brut and was largely based upon the private art collection of the French artist and theorist Jean Dubuffet, now established as a public museum in Switzerland. (The Collection de l'Art brut is housed in the Château de Beaulieu, Avenue des Bergières, Lausanne, Switzerland. Other significant European collections devoted to Outsider Art are the Aracine Collection at the Musée d'art moderne Lille Métropole in Villeneuve d'Ascq, Lille, France; the Musgrave-Kinley Outsider Art Collection, currently housed at the Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin, Ireland; the former De Stadshof Collection, housed at the Museum Dr Guislain in Ghent, Belgium; and the Museum im Lagerhaus at St Gallen, Switzerland.) Fearful that art brut might not go down well with an anglophone readership, my editor proposed that the English term be printed on the title page and the cover, despite the fact that the text proper refers exclusively to art brut. Since 1972, the term Outsider Art has led a life of its own and has been used and abused in a variety of ways, which have often compromised its usefulness as a technical term. I am simply being consistent with my original intention in continuing to use it as a handy anglophone equivalent for art brut.

One of the other key references in my book was the Prinzhorn Collection, the pioneering collection of psychotic art assembled in the early years of the twentieth century by the German psychiatrist Hans Prinzhorn, who worked at the University Clinic in Heidelberg. Prinzhorn was also an art historian and something of a philosopher, and his 1922 book Bildnerei der Geisteskranken (Artistry of the Mentally Ill) is a classic account of the art making of persons diagnosed as psychotic (Prinzhorn 1968). The characteristic styles of such creators are eccentric and diverse, yet all tend to embody a Fremdheitsgefühl (‘a sense of strangeness’), as Prinzhorn puts it, which could be construed as congruent with one of the recognized features of autism. My book also invoked some inflammatory writings by the Viennese artist Arnulf Rainer, a fervent collector of art brut since the 1960s, who speaks of the lunatic artist as one whose expressive acts take place in a notional ‘autistic theatre’, cut off from the normal world of understanding by virtue of its hermeticism and indifference to an outside audience.

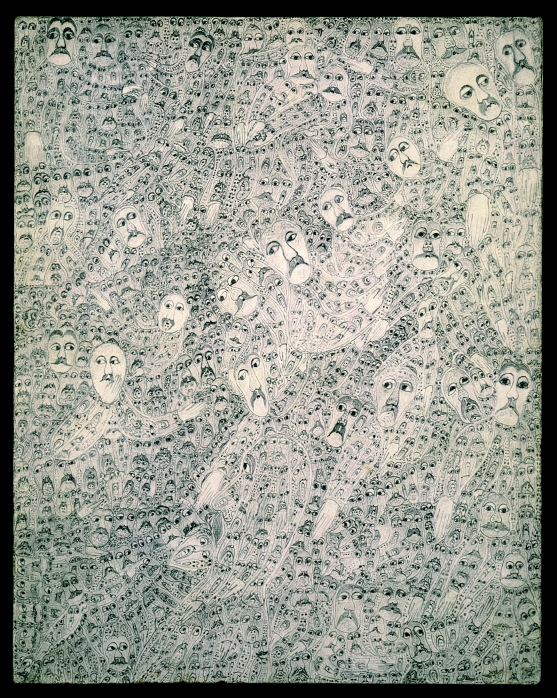

I should point out that the criteria for Outsider Art (art brut) are sufficiently flexible to embrace not only art arising within the context of extreme mental dysfunction, but also art produced by individuals who are quite capable of handling their social lives but who recoil, consciously or unconsciously, from the notion of art being necessarily a publicly defined activity with communally recognized standards. Certain commentators have insisted that true Outsider Art can only be produced by people whose mental lives are at odds with the norm, or who have been physically afflicted in some deeply disturbing way, or again whose social status is pitiful and lacking in all comforts. Thus, there has been a tendency to envisage Outsider Art solely in terms of its makers' aberrant biographies, and to insist that its producers be eccentrics, misfits, recalcitrants, lunatics, convicts, hermits and so forth. But I must insist that, despite the signs that certain unconventional lifestyles and deviant beliefs do contribute to the nourishing of an outsider approach to art, there is a better way of handling the issue of definition: namely, by underlining the anti-conventional nature of the art making itself, its idiosyncrasy, its often unworldly distance from artistic norms, as well as from commonplace experience. I insist that Outsider Art earns its name not because of an association with a lurid case history or a sensational biography, but because it offers its audience a thrilling visual experience. Outsider Art is an art of unexpected and often bewildering distinctiveness, and its outstanding exemplars tend to conjure up imagined private worlds, completely satisfying to their creator yet so remote from our normal experience as to appear alien and rebarbative. Thus, the tireless pen drawings produced by the London housewife and medium Madge Gill (1882–1961) establish an other-worldly environment of flickering patterns out of which peer anxious female faces (figure 1); while the Polish schizophrenic Edmund Monsiel (1897–1962) crams his sheets with hundreds of faces within faces to produce a bemusing prospect of boundless proliferation (figure 2).

Figure 1.

Madge Gill, untitled pen drawing (female face). Courtesy Roger Cardinal.

Figure 2.

Edmund Monsiel, untitled pencil drawing (proliferating faces). Courtesy Henry Boxer Gallery, Richmond, London.

A central element in the definition of Outsider Art, and one particularly cherished by its first theorist Jean Dubuffet, himself a renegade artist, is that it diverges radically from our shared cultural expectation as to what art ought to look like and how it ought to be fashioned (Dubuffet's arguments for an art brut immune to cultural influence are set out in the combative essays; see Dubuffet (1973)). As a mode of independent art making, Outsider Art ignores tradition and academic criteria. Instead, it reflects a strong creative impulse, running free of the communicative conventions to which we are accustomed. At the extreme, such independence can produce styles of expression which may be said to be autistic in the loose, non-clinical sense, i.e. Outsider Art often tends to be secretive, wrapped about, apparently insulated from or indifferent to a potential audience (This line of argument was first essayed in my paper ‘Ars sub rosa. Thoughts on the disposition to secrecy in the work of certain autistic artists’; see Cardinal (1987)).

Now, it is a fact that certain clinically diagnosed autistic persons have distinguished themselves as creators of significant artworks, and thus as exponents of what, for convenience sake, I shall call autistic art. I want to make it clear that it is by no means my wish to enforce a facile equation between Outsider Art and autistic art; yet, what I do want to propose is that it makes sense to situate certain autistic creators within the field of Outsider Art. All the same, if some autists can be deemed to be artists, some only of that number should be counted as Outsider artists.

The exceptional psychic confinement imposed by the autistic condition upon the individual could prompt the untrained enquirer to anticipate finding next to no trace of creativity within the autistic personality. Our cruder ideas about the artistic temperament have been coloured by images of nineteenth- and twentieth-century rebels such as Van Gogh, Munch, Kirchner, Egon Schiele, Francis Bacon, Arnulf Rainer and Georg Baselitz, and have given rise to the stereotype of the bohemian rebel whose creativity leads to noisy gesturing and a rhetorical emphasis that cannot be dissociated from the impulse to create a public spectacle, one not much different from a public nuisance. Art consistent with what is essentially an expressionistic model can be wild, loud and difficult to ignore. Yet, art does not have to be that way, and what I am interested in considering here is the possibility of a quieter, less bombastic idiom arising in conditions of psychological and emotional withdrawal that apparently inhibit normal modes of communication. Such art making can be oddly moving, precisely because it contradicts the stereotype of the noisy hooligan and because it cultivates a characteristic repertoire of marks and signs, creating as it were a peaceful realm of its own, an intimate and vulnerable private world.

I should make it clear that, as a species of art historian or writer about art, I am seeking to open up a perspective onto autistic artmaking, which is, in principle, distinct from the one familiar to the clinical specialist. I am effectively more interested in the autistic drawing as artwork than as scientific document, and the following discussion will doubtless seem inappropriate or futile to those who are used to pursuing unmistakable signals of disease or psychic distortion. I am by no means seeking to disqualify the scientific reading of the semiotics of autism, but I do hope to offer some perceptions of the strange beauty of the art produced within the autistic context. It is a fresh angle on the mystery, perhaps, but it could be that artistic appreciation will shed some light.

2. Six autistic artists

In a well-known case study, the psychologist Lorna Selfe addresses the artistic output of an autistic child called Nadia (b. 1967), who had begun to produce remarkable drawings at the very early age of 3.5 (Selfe 1977; see also Cardinal (1979). Humphrey (1998) offers an interesting comparison with the cave drawings of the Upper Palaeolithic). One of Nadia's inspirations was the conventional and rather cloying imagery found in the Ladybird series of illustrated children's books: she apparently sought to copy a picture of a crowing rooster and another of a horseman blowing his bugle, but her efforts to reproduce the original seem to have gone radically awry, the upshot being a set of scrawled ensembles done with a biro pen, which, at first glance, are hard to construe. We might want to dismiss such work as incompetent and unlovely, were it not that a certain tenacity of manner and consistency of vision do come across. I submit that these ungainly and fantastical images cannot be judged as totally arbitrary and meaningless. There is a sense of an underlying intentionality, a drive towards articulation (even if we might discern an impairment in communication to others). Later on, at the age of 6, Nadia did some sketches of the lower bodies of nurses and women helpers, simply reproducing what, as an infant, she saw in front of her. These sketches have a surprising warmth about them, as if the child meant to convey her affection, a response to the care she was being shown. Within a year or so, as part of a well-meaning attempt to lead the child forward into a positive relation to the social world, Nadia was being taught to read and write, and to do sums; and the process of insistent acculturation seems to have speedily blighted her talent. Her subsequent artwork was stereotyped and normalized, completely losing its fantastical and visionary verve.

The standard of fidelity to the visual has long been a given of Western culture: we tend to feel comfortable with pictures that strongly resemble the world we inhabit. Whether we speak of realism, of naturalism, or of mimeticism, we can find throughout history examples of work the aesthetic virtue of which is judged inseparable from its documentary accuracy. The case of the young autistic artist Stephen Wiltshire (b. 1974) is instructive in this context (see Sacks' (1995) essay on Stephen Wiltshire). Wiltshire had begun drawing at the age of approximately six and impressed his family and teachers by his spontaneous control and meticulous accuracy. The boy's favourite subject matter was architecture. He was able to produce an amazingly faithful representation after no more than a glance at the motif: thus, a day out in London could furnish dozens of (quasi-eidetic) images, which he would subsequently transcribe at speed and with a certain graceful nonchalance. The fact that Sir Hugh Casson, a renowned architect and one-time president of the Royal Academy, became a sponsor of the boy's talent meant that there arose a specific public identification of Wiltshire as an architectural artist. This has led to a prolific output of publications containing drawings of famous cities across the world, to which Wiltshire has been systematically transported. I am impressed by the technical competence of these drawings, but have reservations about their coolness and stylistic sameness. These may be the outcome of external pressure to conform to the expectations of others, or else are simply the result of a particularly well-tuned copying mechanism. At all events, it could be argued that Wiltshire's marked preference for drawing actual buildings distances his pictorial world from that of the imaginative Outsider artist, who creates a coherent and original world of his own. (A useful contrast could be drawn between Wiltshire's art and that of another talented autistic creator, Gilles Tréhin, who, in the course of some 20 years, has produced dozens of drawings to illustrate his fantasy of an island metropolis called Urville. These drawings constitute an accomplished pictorial guide to an entirely chimerical, yet seductively coherent, private world. Accompanied by the artist's own architectural, cultural and pseudo-historical notes, they have seen print as Tréhin (2006).)

James Castle (1900–1977), who lived for much of his life on a lonely farm in rural Idaho, seems never to have been fully examined by the medical profession, although a diagnosis of autism has been ventured a posteriori (Yau 2002; Trusky 2008). His drawings are remarkable, not least in terms of their material constitution, for he favoured a pigment made of soot scraped from a wood stove, mixed with water or saliva and applied to paper or cardboard, usually with a sharpened piece of wood (figure 3). This primitivism of means carries its own pathos and tends to appeal to the Outsider Art connoisseur as confirmation of creative independence. It also represents an involuntary crossover with certain manifestations of twentieth-century avant-gardism whereby minimal marks produced with unsuitable materials have come to be prized within an aesthetic of minimalism. (I am thinking especially of Arte povera, the Italian movement, which delighted in rough surfaces and clumsy scrawls, and of the graffiti-like work of contemporary artists such as Cy Twombly).

Figure 3.

James Castle, untitled drawing in soot and saliva (artist's workplace). Courtesy J. Crist Gallery, Boise, Idaho.

Castle's achievements as a draughtsman are especially noteworthy given the severe constraints on his sensibility. He was thought to have been born deaf (though no proper test was made during his early years), and was deemed to be retarded by many who knew him. As a teenager, he attended the Idaho School for the Deaf and the Blind, but failed to acquire any communication skills and was finally sent home as ‘uneducable’. Thereafter he spent practically all his days loitering about the family farm, never undertaking any work. He might have emerged as a mere idiot observer of circumstance were it not that his images of agricultural buildings and farm paraphernalia possess a conviction, even an aura, that lifts them above the level of crude delineation. Castle seems to be making a deliberate statement about his environment, and his drawings do establish a distinct and recognizable locale. Within it, he seems to have discerned some half-defined quality—something one might love—a quality of recognizable realness, which equally partakes of the unreal, even the surreal. Perhaps it is also the tininess of his work which seduces us; for the drawings are small, almost negligible, and too modestly presented to be assertive. In fact, they were virtually never ‘presented’ to an audience beyond the immediate family. Such discreetness can be compared to the widespread secretiveness of Outsider artists, who often produce prolific work without anyone knowing.

Further aspects of Castle's output reveal considerable inventiveness in both materials and themes. There are hundreds of small ‘artist's books’—pattern books, scrapbooks, stamp albums with home-made stamps, calendars, an illustrated autobiography, codebooks full of secret writing (much of it purely nonsensical, since Castle could barely read), not to mention loose collections of matchboxes and cigarette packs. The model he presents of the restless discoverer and inventor echoes that of such Outsiders as the Swiss schizophrenic Adolf Wölfli (1864–1930), who used collage and drawing to construct a multilayered and preposterous autobiography in image and text; or of another schizophrenic patient, Jean Mar (1831–1911), who penned his gnomic thoughts and unexplained drawings on tiny slips of paper that he hid in small containers.

Roy Wenzel (b. 1959) is a Dutch artist (see Rhodes 2000b). Since the age of 25, he has lived at home in a southern town in Holland, cared for by his brother and sister. He suffered from severe eczema throughout his childhood and was diagnosed as autistic at the age of approximately 11. During therapy sessions in hospital, he began drawing and apparently achieved some remarkable results. Although this early output has not been saved, his adult work has long since entered the art market and been shown in commercial galleries as well as at international exhibitions of Outsider Art. (He was runner-up in the competitive section of the international triennale of Outsider & Naive Art held at the Slovak National Gallery in Bratislava in 2004.) Wenzel's images are highly assertive and gestural. His pictorial scheme tends to imply a traditional perspectival space, albeit his semi-transparent figures are often set across the background in an overlaying technique which suggests an undivided interest both in what is close to and what is far off. The scenes are mainly urban, with rows of houses with rooftops and repetitive rows of windows; we also see buses, cars, trains and ships. The dominant human figure is a large female whose high-heeled boots, huge crimson lips and ample bosom relay a powerful erotic fixation. This figure would easily win an ugliness contest, so that we may choose to celebrate Wenzel as an artist of excess, perhaps placing him in a Netherlandish tradition of Bosch-like grotesquerie.

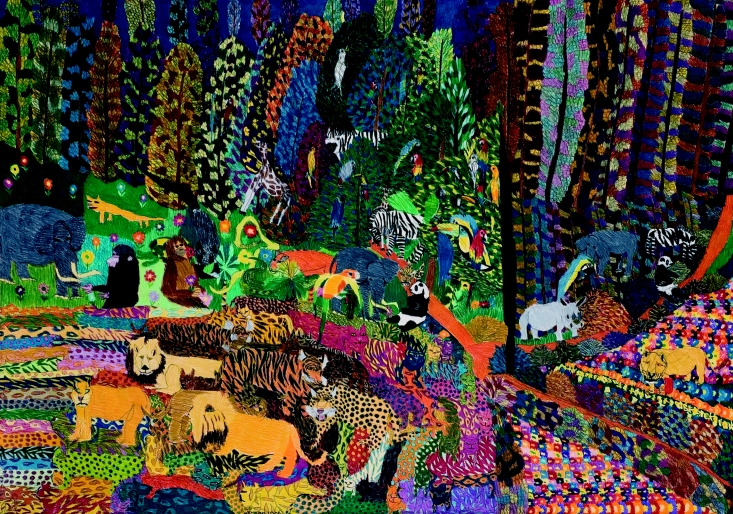

Jeroen Pomp (b. 1985) is another Dutch creator (see Gronert 2008). He makes his pictures in an art workshop located in Rotterdam: the Atelier Herenplaats. Many similar organizations have arisen in the past couple of decades which are dedicated to the fostering of creativity among persons who are physically challenged or have learning difficulties: some of these tend to coax the individual into producing artwork of standard prettiness, following a therapeutic ethos whereby a satisfying picture is the one which deviates the least from a certain norm, never precisely defined yet clearly involving some notion of a desirable standard of technical competence and visual appeal. Pomp, by contrast, operates in an institution whose ethos is radically opposed to any restriction on inspiration. I am told there is neither advice nor tutoring at the Herenplaats, its policy resting on the argument that creativity can only acquire a therapeutic dimension if it is allowed the fullest freedom. Left to his own devices, Pomp has developed an astonishingly colourful style in which objects such as plants and animals proliferate immeasurably (figure 4). (I gather that he is keen on botany and can point out dozens of different plants in some of his pictures.) It must be said, however, that our immediate impression of the work is likely to be one of illegibility. Yet to treat his images purely as puzzles in which clear outlines have been perversely obliterated is to miss the point. It seems to me that there is a palpable zestfulness about the teeming spaces Pomp brings to life. Here is physical and emotional energy made visible: we are looking into a vivid interior reality. And I would argue that the surest sign of an Outsider artist working at full stretch is that we are affected by the bustling dynamism and coherence of a visual (perhaps even a visionary) system, orchestrated by the individual performer. Pomp's private realm may not always be easily legible, but its splendour and wilful momentum are sufficient to induce a positive response—we are privileged to contemplate a strange and thrilling beauty.

Figure 4.

Jeroen Pomp, untitled painting (zoo). Courtesy Hamer Gallery, Amsterdam.

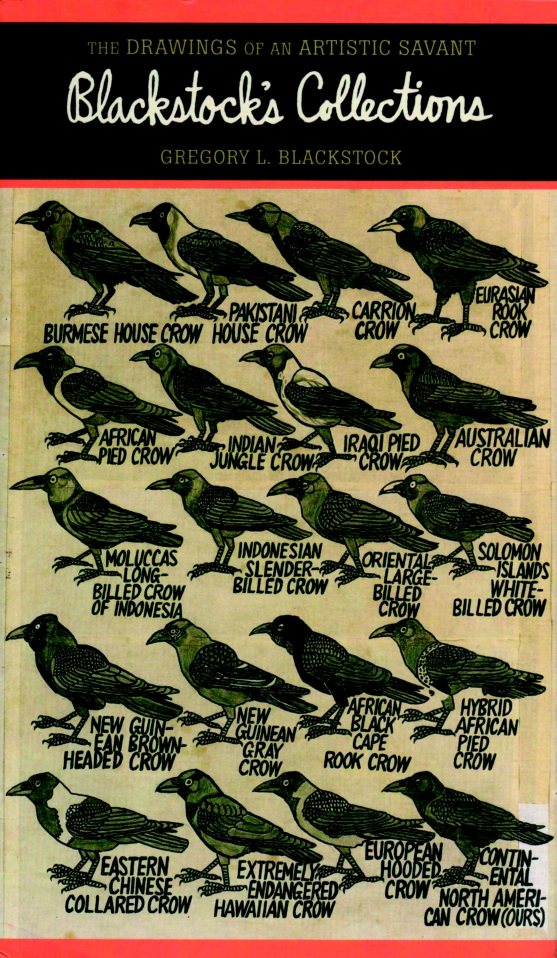

The American artist Gregory Blackstock (b. 1946) has a highly strung personality that keeps him permanently on the qui vive. He was first diagnosed as suffering from paranoid schizophrenia, but this was later amended to autism; today he is situated on the spectrum as a savant. He is reported to be able to speak a dozen languages, and can play from memory on the accordion hundreds of tunes picked up from records. He has prodigious powers of recollection and can cite the names of all the children from his schooldays. One of his party tricks is to inform you of the correct time in Vladivostok or Beijing. He has led quite an unexceptional life, having worked for 25 years as a dishwasher at an athletics club in Seattle; latterly, he has developed a secondary career as a performing musician. Above all, he is a fanatical draughtsman.

Blackstock had his first exhibition in a Seattle gallery at the age of 58. His artistic production began with sketches for the club newsletter, and expanded in relation to his obsessive interest in inventories and taxonomies. He is a great reader of encyclopedias and also visits hardware shops to do sketches of utensils and tools. His work culminated in a published book called Blackstock's Collections and subtitled The Drawings of an Artistic Savant (Blackstock 2006; See also Harmon 2007). Here, we can glimpse something of the man's prodigious appetite for detail and delight in precision and completeness. The individual drawings are diagrammatic, each item being presented plain and simple as the variant of a general type: thus, four dozen kinds of saw are squeezed into a single page, catering to a desire for symmetry as well as completeness. Blackstock's collections include displays of industrial tools (drills, files, saws and trowels), animal life (crows, eagles, ants, owls, wasps and bees, and ‘monsters of the deep’), plant life (berries and tropical fruits), types of vehicle (freight trains and automobiles), buildings (barns, castles and jailhouses), not to mention stringed instruments and mariners' knots (figure 5).

Figure 5.

Gregory Blackstock, cover of his book Blackstock's Collections (2006). Courtesy Princeton Architectural Press, New York.

Here we confront the reproduction of objects that bear witness not so much to the proliferation of things in the actual world, as to the artist's alertness in noticing and documenting all the aspects of difference that distinguish them. This is in fact an instance of autistic repetition in the subtler mode of infinite differentiation. As a species of virtual or theoretical collector, Blackstock is a keen encyclopedist, an ardent completist. His work represents a kind of stocktaking, the reflection of a yearning for order and perhaps ultimately of a longing for mastery over the unthinkable subtleties of our shared world—a desire for supremacy as chief overseer of reality's infinite variations.

Another autistic artist, George Widener (b. 1962), rounds off my brief survey (see Cardinal 2005). Here is another case of amazing savant ‘high functioning’, for Widener can provide swift answers to arithmetical calculations of great complexity. I have listened to him reciting the doubling sequence ‘1-2-4-8-16-32-64-128-256-512...’ at remarkable speed. His party piece is to ask for a person's birthdate and then, within a few seconds, to come up with the day of the week when it fell.

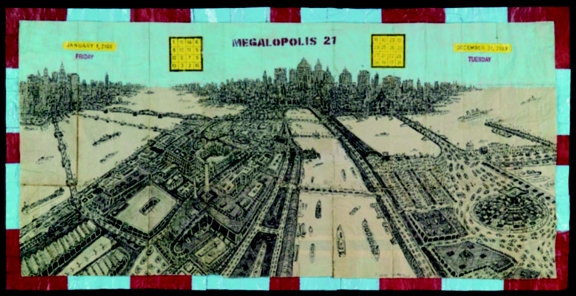

Widener's case history follows a familiar pattern of misdiagnosis—for some time he was thought to be a depressive schizophrenic—and many wretched years of non-alignment with social norms. He was in his thirties when he was admitted to a special university education programme and diagnosed as suffering from Asperger's syndrome. Widener is now classed as a savant. His adaptation to external life is hampered by a certain sluggishness, yet his mental life is hyperactive. Having by now been tested, interviewed and filmed a good many times, he has settled into a routine in which he will trot out a well-rehearsed statement about his early life, his mental condition and the range of his talents: his ease with others is notably at odds with the customary expectations of autism. Widener's passions include numerals and specific historical dates, usually those of catastrophic events, such as the sinking of the Titanic. His passion is for making up calendars which foreground the coincidences arising between various dates and days across history. These home-made time charts represent a form of conceptual art making, based on calculations, symbols and ciphers and incorporating rigorous listings and diagrams. Widener's calendars conform to patterns of association too complex for others to follow, but are seemingly in keeping with a fundamental faith in the efficacy of the numerical system. He is particularly fond of magic squares. I suspect that it is the numerals that give Widener access to a vision of the chaotic prolixity of experience, and numerals again, which allow him to measure and contain that chaos.

Whereas Widener's numerical and taxonomic obsessions are, in effect, extrapolations from objective data (albeit envisaged from a subjective perspective), his pictures of giant cities spring from a more obviously creative area of mental activity. His imagining of a vast and unreal megalopolis must surely be counted an original invention, the summoning-up of a distinctive ‘world’, one which is in perfect accord with the autonomous worlds or cosmologies of Outsider artistry. His compositions often stretch to a metre and more in width, a dramatic scale which seems to belie any idea of secrecy or privacy: I think Widener really does want us to gaze into his personal world. His carefully inscribed marks appear to confirm a network of highly regulated structures, including streets, buildings, towers, bridges and canals. We might note that no people are to be seen in this unreal city, although incessant activity seems implicit. A number of vessels lie at anchor, as if to intimate that his megalopolis lies at the heart of a wider network of ports and unseen continents. I think it is a visionary achievement of considerable finesse and imaginative daring (figure 6).

Figure 6.

George Widener, Megalopolis 21, mixed media drawing. Courtesy Henry Boxer Gallery, Richmond, London.

3. The overlap between autistic art and Outsider Art

Of course, the apparently spontaneous inventions of the untrained creators I have introduced here might serve as objects of medical analysis, in so far as they are construed as direct traces of the autistic condition itself, i.e. they could be read as symptoms. Perhaps we might even envisage them as metaphorical descriptions of autism—attempts at showing, by virtue of a sort of projection from within, what it feels like to be autistic, or again how the world appears when one views it through the autistic window. (There exists, by the way, a rich literature on the forms of psychopathological art, seen as symptomatic of mental disease. And there have been attempts to tie recurrent stylistic traits to specific mental aberrations (see for instance Rennert 1966; Kraft 2005)).

Alternatively—I contend—these works deserve respect as meaningful and intentional artistic compositions. They may not appear communicative, yet they do articulate something, and that something may well be saturated with hidden affect. They are also formal constructs whose properties are sufficiently inventive and engaging as to widen our aesthetic experience in interesting ways. How are we to appreciate and respond to such work?

Let us consider the potential value of a drawing which happens to show us something we recognize as part of the world we inhabit, such as one of Stephen Wiltshire's sketches of County Hall in London or Gregory Blackstock's rendering of a European Hooded Crow. I would suggest that our sense of recognition is in itself a pretty undeveloped or minimal reaction. The approximation of an appearance is not necessarily the highest aim of the creative act, and a skilful copier of reality is arguably somewhat less than an inspired and imaginative artist. In considering the art of autistic persons, we might wish to find something more dramatic or more poignant than the mechanical replication of visual impressions. We would like to find more in the way of emotional or spiritual substance within the image—not just an inert snapshot of the real but an elaboration upon impressions both objective and subjective, an exploration and an extrapolation that go beyond the mimetic minimum.

Since I have no objective proof that autistic persons at large are more creative than other socially or psychologically defined groups, I would not hazard the claim that autism directly encourages inventive drawing. Nevertheless, I do find striking qualities in the work of the autistic creators I have chosen, enough to embolden me to suggest that a special form of aesthetic pleasure might ensue if we attend carefully to their artistry. One of the criteria for the identification of Outsider Art is the sense of its strangeness, its idiosyncrasy; and I have hinted that this strangeness is nothing less than the mark of a coherent private world conjured up in the sweep of imagery of an individual creator. Provided we as viewers can entertain the fantasy of travelling into that world—in the same way that we might travel into a foreign country with no knowledge of its language or customs—we are in a position to savour the extreme experience of otherness, in the form of a seductive exoticism that produces an inarticulate yet intense pleasure. Such a pleasure may be judged strictly irrelevant to any medical concerns, and might even seem to have something of selfish hedonism about it. Nevertheless, I suggest that the images I have invoked do not deserve to be treated simply as confirmations of a diagnosis (one which is in any case confirmed by other behavioural data); and that they implicitly ask us to treat them as intentional statements worthy of serious and responsible consideration.

Here is where autistic artistry may be said to coincide with Outsider artistry. As I have said, not all autistic persons can be Outsiders, but those who merit inclusion in the latter category will exercise the same fascination and stimulate the same level of excitement in the responsive viewer. It is all a matter of comparative intensity and richness. Similar to Outsider Art, autistic art can exercise a magnetism which transcends the simple communication of an appearance or an idea. In the end, it is not that Gregory Blackstock is saying ‘folks, here is a Straight Double-Edge Pruning Saw’, as if that were the priority; but that he is communicating the fact of difference, and the wider fact of the continuum of diversity in the world. Similarly, Nadia's horseman transcends the simple stage of being recognized as a man on horseback and becomes an utterly poignant icon steeped in non-verbalized emotion. James Castle's painstaking reproduction of scenes on his farm—I'm tempted to compare them to the painfully long exposures of the early years of photography—conveys not just a disposition of inanimate roofs, fences and telegraph poles, but an intimate relationship, an act of recognition and homage on the part of an individual who is asserting his links to the narrow domain of the homestead—or rather the wider domain of his imagination. Jeroen Pomp's crammed locales may well be derived from some similar cramming within his invisible inner life, and we can inch closer to appreciating them by first digesting the very fact of our bemusement or claustrophobia. Might our hesitancy about interpreting such pictures be analogous to the hesitancies of classic autism as a state of distrust and confusion regarding the outer world? As for Asperger's and its bewildering communicative excesses, there is again an opportunity for us to move beyond the ticking-off of simple facts and to engage with the dynamic thrust of mental systems unlike our own, in an effort to participate in that alien enthusiasm. At some point, we might catch a glimpse of the inner joy of a Gregory Blackstock or a George Widener when the one completes a particular bout of categorial collecting or the other sees a magic square emerging from an abstruse and extended computation in one of his calendars. Their self-engrossed pleasure in their own mastery can become our secondary pleasure as witnesses thereof, and encourage us to attempt further acts of empathetic response. These should lead us beyond selfish indulgence, for in due course we will find that aesthetic pleasure has begun to coincide with our poignant engagement with another sensibility, another personality; at which point art appreciation is revealed not as a peripheral supplement to human experience but as a privileged medium of human contact itself.

Footnotes

One contribution of 18 to a Discussion Meeting Issue ‘Autism and talent’.

References

- Blackstock G.L. Princeton Architectural Press; New York, NY: 2006. Blackstock's collections. The drawings of an artistic savant. [Google Scholar]

- Cardinal, R. 1972 Outsider Art London, UK: Studio Vista; New York, NY: Praeger.

- Cardinal R. Drawing without words: the case of Nadia. Comparison. 1979;10:3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Cardinal, R. 1987 Ars sub rosa In The Champernowne Trust. Papers presented at the Annual Forum Axbridge, UK: The Axbridge Bookshop, pp. 22–28.

- Cardinal R. The calendars of George Widener. Raw Vision. 2005;51:42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Danchin L. Gallimard; Paris, France: 2006. Art brut. L'Instinct créateur. [Google Scholar]

- Dubuffet J. Gallimard; Paris, France: 1973. L'Homme du commun à l'ouvrage. [Google Scholar]

- Gronert, F. 2008 Jeroen Pomp. In Stendhal Syndrome. Art that makes you go crazy Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Atelier Herenplaats, pp. 255–277.

- Harmon K. The taxonomist: Gregory L. Blackstock. Folk Art. 2007;XXXII:68–75. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey N. Cave art, autism, and the evolution of the human mind. Camb. Archaeol. J. 1998;VIII:165–191. doi:10.1017/S0959774300001827 [Google Scholar]

- Kraft H. Deutscher Ärzte-Verlag; Cologne, Germany: 2005. Grenzgänger zwischen Kunst und Psychiatrie. [Google Scholar]

- Peiry, L. 1997 L'Art brut (transl. Art brut. The origins of outsider art, Flammarion, Paris, 2001). Paris, France: Flammarion.

- Prinzhorn H. Springer; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; New York, NY: 1968. Bildnerei der Geisteskranken. Ein Beitrag zur Psychologie und Psychopathologie der Gestaltung [1922] (transl. by E. von Brockdorff (1972) as Artistry of the mentally ill, Springer, New York, NY) [Google Scholar]

- Rennert H. G. Fischer; Jena, Germany: 1966. Die Merkmale schizophrener Malerei. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes C. Thames & Hudson; London, UK; New York, NY: 2000a. Outsider Art. Spontaneous alternatives. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes C. De Stadshof; Zwolle, The Netherlands: 2000b. Roy Wenzel. Works on paper. [Google Scholar]

- Sacks, O. 1995 Stephen Wiltshire, ‘Prodigies’. In An anthropologist on Mars. Seven paradoxical tales, pp. 179–232. London, UK: Picador.

- Selfe L. Academic Press; London, UK: 1977. Nadia. A case of extraordinary drawing ability in an autistic child. [Google Scholar]

- Tréhin G. Jesssica Kingsley Publishers; London, UK; Philadelphia, PA: 2006. Urville. [Google Scholar]

- Trusky T. Boise State University; Boise, Idaho: 2008. James Castle. His life and art. [Google Scholar]

- Yau J. Knoedler & Co; New York, NY: 2002. James Castle. The common place. [Google Scholar]