INTRODUCTION

Catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation (AF) is a useful treatment option for this common arrhythmia, reducing morbidity compared to drug therapy1. Methods and technology have improved in recent years, and it is has even been offered as first-line therapy in a few experienced centers2. Despite the promise of catheter ablation, a variety of serious complications have been reported, including pulmonary vein stenosis, cardiac perforation, thromboembolism, vascular complications, and phrenic nerve injury. Atrioesophageal fistula, thought to result from thermal injury of the esophagus due to its close apposition to the posterior left atrial (LA) wall3, is a rare but often fatal complication of catheter ablation for AF4.

Several methods have been proposed for detecting and avoiding esophageal injury during left atrial catheter ablation, including fluoroscopic contrast visualization of the esophagus during the procedure5, which provides a rough guide but may underestimate the size of the esophagus6. Temperature monitoring also offers a means of detecting intraprocedural esophageal heating so radiofrequency application at that site can be discontinued7, 8. However, only a few active techniques for esophageal protection have been proposed, including mechanical deflection of the esophagus9 and active esophageal cooling10. These have not been widely used during ablation procedures; most experts advise simply limiting energy delivery near the esophagus and monitoring for heating. Our group has previously used an intra-pericardial balloon to protect the phrenic nerve during a catheter ablation procedure11. In the current communication, we demonstrate a novel technique, inflating an intra-pericardial balloon between the left atrium and esophagus to prevent esophageal injury during ablation of the posterior LA wall.

CASE REPORT

A 57-year-old male with history of highly symptomatic paroxysmal AF, refractory to amiodarone and propafenone therapy, was referred for consideration of catheter ablation. The patient had a structurally normal heart, with past medical history significant only for Graves Disease, controlled with propylthiouracil. He previously had undergone circumferential pulmonary vein (PV) ablation 18 months earlier, but complete PV isolation could not be achieved due to the position of the esophagus, which was directly adjacent to the left-sided pulmonary veins as seen by esophageal contrast imaging. During the first procedure, care was taken to avoid radiofrequency application near the esophagus, and there were no complications. The patient had some improvement in symptoms following this procedure, but about 12 months later had recurrence of palpitations and fatigue and was found to have frequent episodes of atrial fibrillation despite another trial of antiarrhythmic medication. Repeat MRI showed normal left ventricular function and mild left atrial enlargement. The esophagus was seen to lie directly adjacent to the ostium of the left inferior PV (Figure 1). The patient was referred for a second radiofrequency catheter ablation procedure, this time with epicardial access to attempt more complete PV isolation and protect the esophagus if necessary.

Figure 1. Pre-procedural magnetic resonance imaging.

showing close approximation of posterior left atrial wall and esophagus in axial (A) and sagittal (B) views. The lack of separation between atrium and esophagus precluded adequate RF energy delivery to isolate the left inferior pulmonary vein during the first ablation procedure.

After induction of general anesthesia, standard multipolar electrophysiology catheters were advanced through the femoral veins to the right atrium, right ventricular septum, and His bundle. A coronary sinus catheter was placed using the internal jugular vein. Epicardial access was obtained via subxiphoid puncture and an 8 French SL0 sheath (St. Jude Medical) was advanced into the pericardial space. A double transseptal puncture was performed to pass two 8 French SL0 sheaths into the left atrium. Intravenous heparin was given to maintain activated clotting time over 300 seconds. Liquid barium suspension was delivered by orogastric tube to allow fluoroscopic visualization of the esophagus, and a probe was advanced into the esophagus for continuous temperature monitoring during the ablation procedure. A Lasso circular multipolar catheter (Biosense Webster, Diamond Bar, CA) was used for mapping the pulmonary veins, and a Celsius Thermocool 3.5-mm irrigated tip catheter (Biosense Webster, Diamond Bar, CA) was used for circumferential pulmonary vein ablation. Power during RF delivery was limited to 30 Watts (25 Watts near the esophagus). No difficulty was encountered in mapping and isolating the left superior, right superior and right inferior pulmonary veins. However, the medial antral region of the left inferior pulmonary vein (LIPV) was immediately adjacent to the esophagus on multiple fluoroscopic views. This vein could not be isolated due to concern about thermal esophageal injury.

In order to safely ablate near the LIPV, a Meditech 18-mm × 4-cm balloon catheter (Meditech, Boston Scientific) was advanced through the pericardial space over a guidewire, to the oblique sinus immediately adjacent to the posterior left atrium. When it was positioned between the left atrium and the esophagus, the balloon was inflated, deflecting the LIPV and its antrum laterally and away from the esophagus (Figure 2).

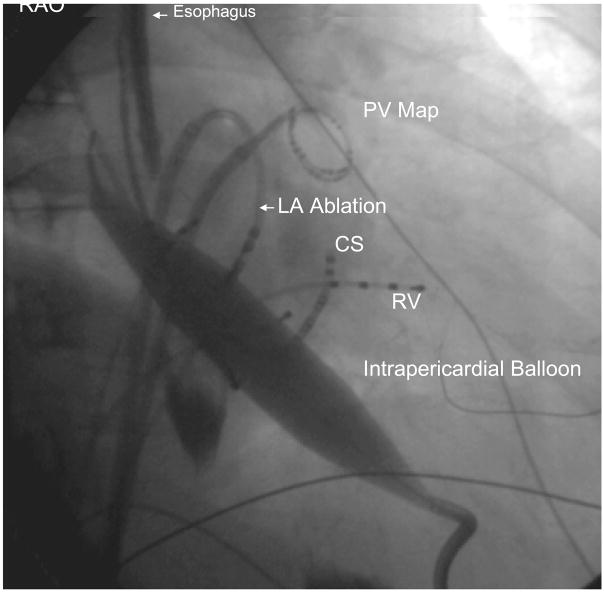

Figure 2. (A) Left anterior oblique (LAO) and 2 (B) Right Anterior Oblique (RAO) images of catheter and balloon position during isolation of left inferior pulmonary vein.

Epicardial access to the oblique sinus allowed positioning of an intra-pericardial balloon over a guidewire. After the balloon was manipulated to lie between the left atrium and esophagus at the site of intended endocardial ablation, it was inflated to increase the separation between esophagus and ablation catheter, which was positioned near the ostium of the left inferior pulmonary vein. PV Map = pulmonary vein mapping catheter, LSPV = left superior pulmonary vein, RA = right atrial catheter, RV = right ventricular catheter, ICE = intracardiac echocardiography catheter, His = His bundle catheter, CS = coronary sinus catheter.

Figure 2 B. Right Anterior Oblique (RAO) image

Full balloon inflation was confirmed based on the balloon’s profile in the RAO and LAO views (Figure 2A and 2B). Despite position of the balloon directly posterior to the LA, there was no appreciable hemodynamic effect during or after balloon inflation, perhaps due to pericardial compliance or lack of cardiac compression. Electroanatomic mapping (EnSite system, St. Jude Medical, St. Paul, Minnesota) was used to measure the distance from an ablation catheter near the LIPV antrum and a quadripolar electrophysiology catheter in the esophagus, before and after balloon inflation (Figure 3). With both increased separation and the intervening balloon catheter to protect the esophagus, endocardial antral isolation could be completed safely. The distance between the catheter in the esophagus and the PV before balloon inflation was 9 mm, which increased to 22 mm during balloon inflation. No heating of the esophagus was observed, and electrical isolation of the vein was successful. At the conclusion of the procedure, a pericardial drain was left in place due to blood-stained fluid return from the pericardial space. There was no evidence of tamponade and the drain was removed the following day. The patient did not require transfusion. He was discharged home on the second post-procedure day. He had one episode of AF in the hospital on the day following the procedure. At 5 months of follow-up he has had no esophageal complication and is free of arrhythmia symptoms.

Figure 3.

Three-dimensional electroanatomic image of the left atrium and pulmonary veins, right posterior oblique view. During balloon inflation, within the oblique sinus, the left inferior pulmonary vein was moved upward and laterally, away from the esophagus. LAA = Left atrial appendage, LSPV = Left superior PV, LIPV = Left inferior PV, RSPV = Right superior PV, RIPV = Right inferior PV, ESO = esophagus.

DISCUSSION

In this case we describe a novel method for preventing esophageal injury during catheter ablation of the posterior left atrium for atrial fibrillation, increasing separation of left atrium and esophagus by inflation of an intra-pericardial balloon. For those cases in which the position of the esophagus prevents creation of lesions, the technique could offer an opportunity to improve both the safety and efficacy of the catheter ablation procedure. It remains to be seen how it compares to other techniques such as esophageal deflection or cooling, or the use of alternative energy sources such as cryotherapy, in preventing atrioesophageal fistula.

Catheter ablation holds promise in the treatment of atrial fibrillation, an arrhythmia poorly controlled with medical therapy alone. However, both safety and efficacy must be improved before ablation can be widely recommended as first-line therapy. Since this procedure is currently intended to reduce symptoms rather than save lives, the need to limit serious and life-threatening complications is obvious. While several methods of preventing atrioesophageal fistula have been proposed, most rely on avoiding energy delivery near the esophagus, or detecting esophageal heating after it has occurred, rather than actively protecting the esophagus. In certain cases such as the one described here, the site of desired radiofrequency application is directly adjacent to the esophagus. Achieving a favorable procedural outcome requires taking steps to prevent esophageal injury.

LIMITATIONS

Some important limitations of this method should be noted. First, it requires epicardial access, which is not performed in all ablation centers and carries its own inherent risks. Second, this is a report of a single case without long-term follow-up, and should be viewed only as a demonstration of feasibility. To show safety and efficacy of approaches such as intra-pericardial balloon deflection for preventing esophageal injury, a prospective study including more patients will be required.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the NHLBI, R01HL084261 (Dr. Shivkumar)

The authors thank Ms. Michelle Betwarda for assistance with the collation of this manuscript

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Pappone C, Rosanio S, Augello G, et al. Mortality, morbidity, and quality of life after circumferential pulmonary vein ablation for atrial fibrillation: outcomes from a controlled nonrandomized long-term study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:185–197. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00577-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verma A, Natale A. Should atrial fibrillation ablation be considered first-line therapy for some patients? Why atrial fibrillation ablation should be considered first-line therapy for some patients. Circulation. 2005;112:1214–1222. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.478263. discussion 1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lemola K, Sneider M, Desjardins B, et al. Computed tomographic analysis of the anatomy of the left atrium and the esophagus: implications for left atrial catheter ablation. Circulation. 2004;110:3655–3660. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000149714.31471.FD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cummings JE, Schweikert RA, Saliba WI, et al. Brief communication: atrial-esophageal fistulas after radiofrequency ablation. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:572–574. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-8-200604180-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamane T, Matsuo S, Date T, et al. Visualization of the esophagus throughout left atrial catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006;17:105. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2005.00286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gula LJ, Skanes AC, Posan E, et al. Images in cardiovascular medicine. Gastroesophageal reflux facilitates esophageal imaging during pulmonary vein ablation. Circulation. 2006;114:e235–236. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.614735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Redfearn DP, Trim GM, Skanes AC, et al. Esophageal temperature monitoring during radiofrequency ablation of atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2005;16:589–593. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2005.40825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cummings JE, Schweikert RA, Saliba WI, et al. Assessment of temperature, proximity, and course of the esophagus during radiofrequency ablation within the left atrium. Circulation. 2005;112:459–464. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.509612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herweg B, Johnson N, Postler G, et al. Mechanical esophageal deflection during ablation of atrial fibrillation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2006;29:957–961. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2006.00470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsuchiya T, Ashikaga K, Nakagawa S, et al. Atrial fibrillation ablation with esophageal cooling with a cooled water-irrigated intraesophageal balloon: a pilot study. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2007;18:145–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buch E, Vaseghi M, Cesario DA, et al. A novel method for preventing phrenic nerve injury during catheter ablation. Heart Rhythm. 2007;4:95–98. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]