Abstract

Herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1) represents a significant obstacle for vaccine designers, despite decades of investigation. The virus primarily infects the host at vulnerable mucosal surfaces that progresses to lesion development, latency in nervous tissue, and possible reactivation. Therefore, protection at the site of infection is crucial. Mucosal adjuvants are critical for the development of an effective vaccine approach and heat-shock protein 70 (Hsp70) represents an attractive candidate for this purpose. This study demonstrates that Hsp70 coupled to gB498-505 from HSV-1 induced mucosal and systemic priming of CD8+ T cells capable of protecting C57BL/6 mice against a lethal vaginal challenge. Elevated gB-specific cytotoxicity was observed in the spleen of mice immunized with conjugated Hsp70 and gB498-505. In addition, both vaginal IFNγ levels and viral clearance were enhanced in mice mucosally immunized with Hsp70 and gB peptide versus peptide only control mice or mice receiving Hsp70 and a control peptide. These studies demonstrate that Hsp70 can be used as an effective mucosal adjuvant capable of generating a protective cell-mediated immune response against HSV-1.

Keywords: mucosal immunity, herpes simplex virus, heat shock protein, CD8+ T cell, vaccine

Introduction

Despite decades of research and development, effective vaccines against a number of viral pathogens, such as HIV and a number of human herpesviruses, are still lacking. It appears that T cell immunity, including both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, are crucial for controlling and eliminating these chronic viral infections. Despite decades of attempts, no licensed vaccine strategy has proved effective against herpes simplex virus (HSV) in human trials. Therefore, additional, novel approaches are necessary and warrant investigation. A number of vaccine approaches, both systemic and mucosal, have been investigated against HSV.1,2 Some examples include DNA vaccines along with various cytokine and chemokine adjuvants,3–5 CpG oligonucleotide motifs along with peptide,6,7 heat-shock protein/peptide complexes,8–10 recombinant vaccinia virus expressing HSV glycoproteins11 and many others. Moreover, it appears that heat shock protein 70 (hsp70) coupled to viral peptides may prove useful as vaccine candidates for HSV. Hsp70 has been demonstrated to induce the maturation and migration of dendritic cells (DC),12 leading to the upregulation of costimulatory molecules and the secretion of strong proinflammatory cytokines as well as Th1 associated chemokines.13–16 Recent studies from our group demonstrated that when hsp70 was coupled to gB498-505, the dominant CD8+ T cell epitope in C57BL/6 mice against HSV-1, it induced potent acute responses marked by enhanced levels of IFNγ secreting cells and strong cytotoxic T cell (CTL) activity. Unfortunately, these responses were not durable, as mice challenged in the memory phase gradually lost resistance to viral challenge in comparison to groups that were immunized with UV-inactivated HSV-1 or a recombinant vaccinia virus encoding gB498-505 as a minigene.8 This decrease was attributable to the lack of CD4+ T cell help during the priming phase. Therefore, additional studies including cognate CD4+ T cell help increased long-term effectiveness and memory responses.9

HSV is primarily transmitted via mucosal surfaces, such as the oral and genital mucosae. Therefore, efficient immune responses are critical for protection at these vulnerable sites, and development of vaccine approaches to enhance mucosal immunity against HSV is a major goal.17,18 The respiratory tract is an attractive route of administration to induce protective immune responses to mucosal pathogens, especially since immune cells primed at the primary mucosal site appear to migrate to distal mucosal sites, such as the vaginal mucosa. This process has been referred to as the common mucosal concept.19 Several effective mucosal adjuvants have been tested in HSV vaccine trials, and one of the more potent of these in clinical trials in humans was 3-O-deacylated monophosphoryl lipid A given along with recombinant HSV-2 glycoprotein D in aluminum hydroxide.20 Unfortunately, the vaccine was only effective in women seronegative for both HSV-1 and HSV-2. Other bacterial toxins, such as cholera toxin and E. coli enterotoxin, are strong mucosal adjuvants, but significant side effects prevent their practical use in humans.21 Another possible mucosal adjuvant, CpG motifs, has also been investigated in mucosal HSV vaccine studies by the Rosenthal group.7 Mucosal CpG administration along with recombinant protein from HSV was an effective approach, generating high levels of CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses as well as HSV-specific antibody responses. Even CpG alone was surprisingly effective at preventing vaginal HSV infection for a short period, presumably because of enhanced stimulation of innate immunity.22 In this study we evaluate the potential use of hsp70 as a mucosal adjuvant. It should be noted that another group has also explored mucosal immunization (vaginal and rectal administration of macaques) using hsp70 and HIV peptides with some success.23 In our studies mice were given hsp70 bound to gB498-505 intranasally (i.n.) or intraperitoneally (i.p.) and the resulting systemic CTL response was measured. Resistance to vaginal challenge with HSV-1, vaginal cytokine production, and clearance of virus were also examined. Our results indicate systemic responses to gB498-505, increased vaginal IFNγ levels, enhanced viral clearance rates, and resistance to vaginal challenge in mice that received hsp70 bound to gB498-505 either i.n or i.p.

Results

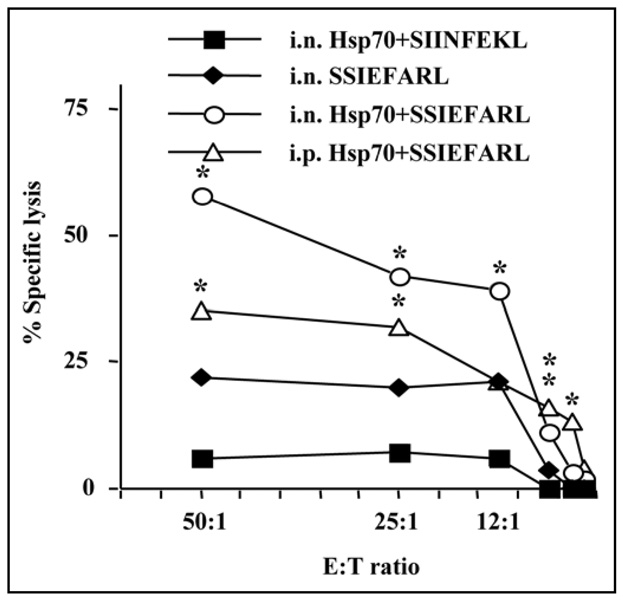

Mucosal immunization with hsp70 and gB peptide results in systemic gB-specific cytotoxic T cell responses

A standard cytotoxic T cell assay was used to examine the level of systemic CTL activity that was generated in each experimental group. Mice were immunized a total of three times i.n or i.p. with hsp70 and gB peptide as previously described. Five days after the final boost the spleen was removed and pooled splenocytes were restimulated for five days in the presence of irradiated syngeneic splenocytes loaded with gB peptide. A standard Cr51 release assay was then performed to assess cytotoxic function. As seen in Figure 1, both groups that received hsp70 coupled to gB peptide mounted enhanced CTL responses in comparison to control groups immunized with hsp70 and control peptide or gB peptide alone. Differences at E:T ratios from 3:1 to 50:1 were statistically significant between experimental and control groups (except the E:T of 12:1 for the i.p. imuunized hsp70 + SSIEFARL). At the highest effector to target ratio (50:1) mice i.n. immunized with hsp70 and gB peptide yielded a specific lysis of over 60%, while control mice given gB peptide alone showed less than 20% lysis. It is interesting to note that mice receiving i.n. hsp70 and SSIEFARL mounted slightly higher CTL activity in comparison to i.p. administered mice (60% versus 34% specific lysis). Mice given hsp70 and ova peptide yielded minimal killing (less than 10%), regardless of the route of administration.

Figure 1.

Spleen CTL activity following systemic or mucosal Hsp70 + SSIEFARL immunization 7 d after the final boost using a standard 4 h 51Cr release assay reveals increased cytotoxicity in hsp70 mucosally immunized mice. Various E:T ratios were performed using MC38 target cells loaded with gB498-505. Data are from pooled samples of six mice per group. Results are representative of two independent experiments. *p < 0.05 (Hsp70 + SSIEFARL i.n or i.p. versus either control group).

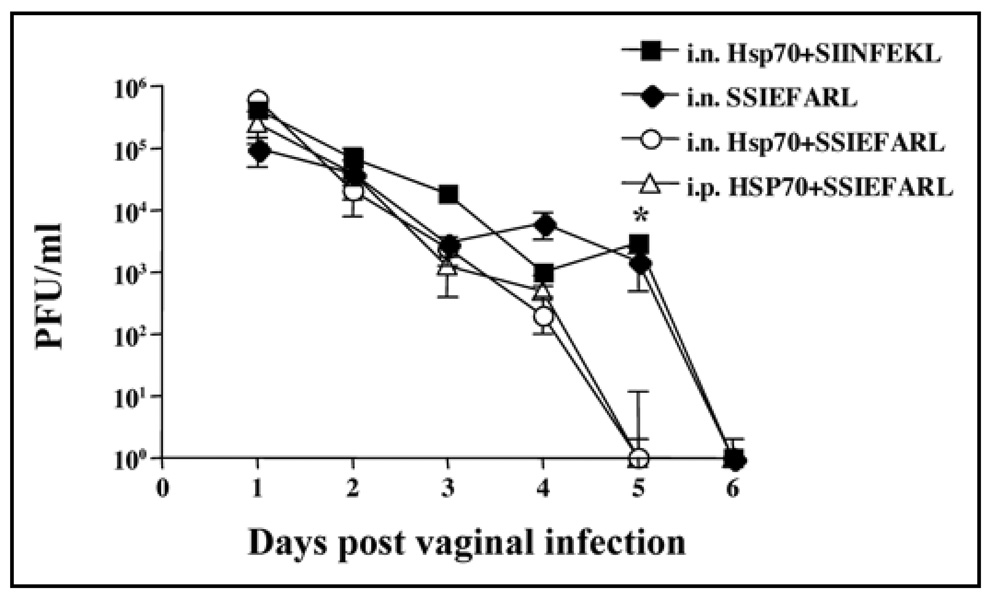

Mucosal immunization with hsp70 and gB peptide results in an enhanced viral clearance rate

We next set out to determine if such enhanced CD8+ T cell responses were capable of affecting the rate of viral clearance following a high dose mucosal vaginal challenge with HSV-1 McKrae. Mice were synchronized with Depo-Provera as before and challenged with HSV-1 on day 4 after the final booster. Vaginal washings were then taken on each day to determine viral titres. As seen in Figure 2, mice that were previously immunized either i.n. or i.p. with hsp70 and gB peptide were able to clear virus from the vagina at a slightly faster rate than control groups. In addition, groups receiving hsp70 and gB peptide, both i.n and i.p., were able to completely clear virus one day earlier than control groups (4 days versus 5 days for control groups). In addition, this day 5 difference was statistically significant. This suggests that viral clearance rate is enhanced moderately following either mucosal immunization or systemic immunization with hsp70 and gB peptide in comparison to hsp70 and control peptide or gB peptide alone.

Figure 2.

Mice receiving hsp70 + SSIEFARL either i.p. or i.n. clear HSV-1 one day sooner than control groups. Mice were infected five days after the final immunization and vaginal titres were measured by plaque assay. Results are representative of three independent experiments of six mice per group. *p < 0.05 (Hsp70 + SSIEFARL i.n or i.p. versus either control group).

Mice immunized mucosally with hsp70 and gB peptide secrete elevated amounts of IFNγ in vaginal washings following challenge with HSV-1

Throughout the challenge with HSV-1 McKrae daily vaginal washings were collected to examine IFNγ levels throughout the course of infection. Figure 3 shows that mice that received hsp70 and gB peptide i.n. demonstrated higher initial levels (two-fold enhancement) of IFNγ early on during infection and also mounted a delayed, statistically significant production of IFNγ (400 +/− 153 pg/ml) observed on day 4 p.i., which was completely absent in all other groups. This delayed production of IFNγ is most likely attributable to infiltrating memory CD8+ T cells. The early enhanced IFNγ response in mice i.n. immunized with hsp70 and gB498-505 is most likely due to a combination of tissue residing effector memory CD8+ T cells or an elevated NK cell response in relation to the other groups.

Figure 3.

Elevated amounts of IFNγ are secreted in response to HSV-1 McKrae vaginal infection from mice mucosally immunized with hsp70 and SSIEFARL. Data were obtained from vaginal washings performed every 24 h with PBS followed by ELISA for detection of IFNγ. Results are representative of three independent experiments of six mice per group. *p < 0.05 (Hsp70 + SSIEFARL i.n or i.p. versus either control group).

Mucosal immunization with hsp70 and gB peptide grants protection against a lethal vaginal challenge with HSV-1

Immunized mice were subjected to a lethal challenge (106 pfu) with HSV-1 McKrae, a highly virulent strain that often results in paralysis and death in unimmunized mice, in an effort to test if mucosal immunization with hsp70 and gB peptide was effective at controlling or preventing a vaginal HSV-1 infection. Mice were immunized as previously described and then synchronized as described in the materials and methods prior to challenge. According to previous studies, synchronization of the estrous cycle is an important factor for susceptibility to vaginal infection with HSV-1.24,25 Mice were vaginally challenged and scored for disease as described in materials and methods. As evident in Figure 4, only mice that were immunized i.n with hsp70 and gB peptide were significantly protected from disease and death. Mice that received hsp70 and SSIEFARL i.p. demonstrated a reduced disease course and moderate resistance to encephalitis and death, as 66% of the mice fully recovered. Mice that received hsp70 and control ova peptide or those that received gB peptide alone developed severe disease, and most, if not all, succumbed to infection.

Figure 4.

Mice that receive mucosal administration of hsp70 and SSIEFARL are resistant to vaginal challenge with HSV-1 during the acute phase response. Mice were vaginally challenged with HSV-1 McKrae strain (106 pfu) five days after the final hsp70 + peptide immunization. Grading was performed daily as follows: (1) mild vaginal inflammation, (2) moderate inflammation and swelling, (3) severe inflammation, ulceration and hair loss, (4) paralysis and (5) death. Results are representative of three independent experiments of six mice per group. *p < 0.05 (Hsp70 + SSIEFARL i.n versus either control group).

Discussion

The present study assesses the efficacy of mucosal immunization with hsp70 in conjunction with the immunodominant CD8 epitope found in C57BL/6 mice from HSV-1, gB 498–505. In addition, the mucosal route of administration was compared to another systemic route, i.p. administration. These two vaccination approaches were then compared in their ability to generate systemic CTL activity, increase resistance to vaginal challenge, enhance vaginal cytokine levels, and enhance viral clearance rate. Hsp70 coupled to gB498-505, regardless as to the route of administration, primed a systemic response in the spleen as measured by a standard Cr51 release assay. In addition, it appears that i.n. administration of hsp70 and gB498-505 lead to enhanced IFNγ levels in the vaginal lumen, faster clearance of virus, and elevated resistance to vaginal challenge. Enhanced levels of vaginal IFNγ may be a critical factor for the observed resistance to disease, and this has been carefully documented before.26 It is also interesting to speculate upon the source of the enhanced early levels of IFNγ in vaginal washings (24 h). The source is most likely NK cells, which have shown to play a critical role in the early control of HSV,27 or effector memory CD8 T cells. More interesting, it appears that mucosal administration of hsp70 and gB498-505 is more effective than i.p. administration in reference to the ability of each regimen to protect against vaginal challenge.

Several reports have demonstrated the efficacy of hsp70 and peptide to act as an effective vaccine against viral infection in mice, most notably in the LCMV system by the Welsh group and studies in our own lab.8,28 However, all murine hsp70 strategies to date have utilized either i.p., intradermal (i.d.), or s.c. immunization routes. Our own group has demonstrated that i.p. immunization with hsp70 and gB498-505 generates potent acute responses, but these responses decay over time in comparison to groups immunized with a recombinant vaccinia virus expressing gB498-505.8 This difference was most likely attributable to a lack of CD4+ T cell help during priming in the hsp70 groups, and additional work showed that the addition of cognate CD4+ T cell help was sufficient to greatly improve long-term responses.9 In addition, studies from our own lab using CpG and gB498-505 also demonstrated a lack of long-term durability, as mice challenged in the memory phase showed reduced resistance to viral challenge.6 It is likely that long-term protection would also diminish in mice mucosally immunized with hsp70 and peptide, much like that observed in earlier studies. Clearly, additional work is needed including possible CD4 epitopes, such as adding recombinant full-length gB, to possibly enhance the acute as well as long-term memory response. Other possibilities for improvement include the use of hsp70 and peptide as either a priming or boosting agent along with recombinant vaccinia virus expressing gB or plasmid DNA encoding gB. Prime-boost mucosal vaccination against HSV-1, as previously demonstrated, was more effective when the recombinant vaccinia virus rather than plasmid DNA was used during the priming step rather than the boost.29 Perhaps hsp70 and peptide approaches would also be more effective as a booster immunogen, especially since CD4+ T cell help may not be as essential during the booster stage. This concept is currently under investigation. In addition, further work is warranted to determine the effects upon maturation and migration that hsp70 exposure may exert upon respiratory DC, which are typically resistant to maturation signals in comparison to other tissue compartments such as the spleen.30 Therefore, this approach would likely only attenuate disease course at best in a long-term situation.

Overall, this study is the first to investigate the possible use of hsp70 as a mucosal adjuvant capable of priming protective CD8+ T cell responses against HSV. In humans it has been demonstrated that CD8 T cell responses are closely linked to HSV control and clearance. Therefore, approaches stimulating immunity may prove beneficial in a clinical setting, especially since many HSV peptide epitopes for several common HLA Class I haplotypes have been discovered in recent years.1,2 We demonstrate that hsp70 is a potential mucosal adjuvant capable of inducing elevated IFNγ in the vagina in response to infection, increased viral clearance, as well as elevated systemic CTL activity and overall protection from disease. Additional work fully characterizing the nature and level of the CD8+ T cell response within mucosal tissues should add further support for this approach.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Four- to five-week-old C57BL/6 (H-2b) mice were purchased from Harlan Sprague-Dawley (Indianapolis, IN). In conducting the research described in this work we adhered to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals as proposed by the committee on care of Laboratory Animal Resources Commission on Life Sciences of the National Research Council. The facilities are fully accredited by the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care.

Peptides

The HSV gB (amino acids 498 to 505) peptide SSIEFARL and the chicken ovalbumin (aa 257 to 264) peptide SIINFEKL were synthesized and supplied by Research Genetics (Huntsville, AL)

Viruses

HSV-1 McKrae strain was grown on Vero cells (ATCC catalog no. CCL81), titrated, and stored in aliquots at −80°C until use. Viral titrations were performed on Vero cell monolayers and PFU/ml was calculated.

Recombinant hsp70 protein preparation

The murine hsp70 gene was amplified using high-fidelity PCR from the hsp70.1 gene from a plasmid kindly provided by S. Calderwood.31 It was then inserted into the pET-22b+ expression vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) using an engineered 5′ NdeI site and a 3′ BamHI site. The insert was then sequenced for confirmation. Recombinant protein was then produced in transformed BL21 (DE3) E. coli (Invitrogen) and purified as previously described.32 In brief, the bacteria were lysed using a french press following a 4 hour isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactoside (IPTG) induction and then dialyzed in binding buffer. The dialyzed lysate was then purified using ATP-agarose affinity chromatography, dialyzed in binding buffer, and then further purified by ion exchange chromatography to remove any contaminating DnaK (Q sepharose was used rather than POROS HQ). The final elute was then dialyzed in PBS. Western blot analysis demonstrated a single band at approximately 70 kD. Limulus amebocyte lysate testing (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, MD) revealed that the final protein product contained only trace levels of endotoxin (3 EU/ml).

Cell lines

Vero (African green monkey kidney cell line) was used for growing of viral stocks and MC38 was used as a target cell (C57BL/6 adenocarcinoma, H-2b). All cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modification of Eagle’s medium (Mediatech, VA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 5 mg/L of gentamicin sulfate and 2 mM L-glutamine. T cell stimulation assays were carried out in 25 mM Hepes buffered RPMI-1640 media (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 5 mg/L of gentamicin sulfate, 0.05 mM 2-ME and 2 mM L-glutamine.

Hsp70 and peptide binding

SSIEFARL and SIINFEKL peptides were loaded onto hsp70 according to a previously described procedure.28 Briefly, peptides were incubated with hsp70 in binding buffer (phosphate-buffered saline with 2 mM MgCl2) at 37°C for 60 min (10 µg each in 50 µl total vol, 75:1 molar ratio). ADP was then added to 0.5 mM (Sigma) and the incubation was continued for another 60 min.

Immunizations

C57BL/6 mice were immunized either i.n. or i.p. with either 10 µg of SSIEFARL or SIINFEKL coupled to 10 µg of hsp70 in binding buffer for a total volume of 20 µl (i.n.) or 100 µl (i.p.). Some groups received only SSIEFARL peptide. Immunizations were performed on d0, d7 and d21. Spleen responses were then assessed 5 d after the final boost.

CTL assay

The CTL assay was performed as described earlier.6 Briefly, pooled effector cells generated after a 5 d in vitro expansion (with SSIEFARL-loaded, irradiated splenocytes) were analyzed for their ability to kill major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-matched antigen-presenting targets. The cells were mixed with the target at various ratios and incubated for 4 h. The targets included 51Cr-pulsed MHC-matched SSIEFARL-pulsed as well as control SIINFEKL-pulsed MC38 target cells. Percent specific lysis was then calculated according to the following formula:

ELISA

ELISA was performed as previously described to determine cytokine levels (IFNγ) in vaginal washings.6 Briefly, 96-well EIA/RIA plates were coated with capture antibody for IFNγ (RA-6A2) (BD Pharmingen) ON @ 4°C (2 µg/ml) in 1 M Na2HPO4. The wells were then washed with PBS-Tween and vaginal washings taken every 24 h with PBS were incubated ON @ 4°C. For detection wells were washed with PBS-Tween and biotin anti-mouse IFNγ (XMG1.2) (BD Pharmingen) (1 µg/ml in PBS 3% BSA) was then added to each well and incubated for 1 h @ RT Wells were then washed with PBS-Tween and streptavidin-conjugated peroxidase (Jackson Laboratories, ME) in PBS 3% BSA was added to each well (1 µg/ml) for 30 min @ RT. Plates were then washed and developed using 2,2′-Azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)diammonium salt (ABTS) (Sigma). ELISA readings were taken on an automated ELISA reader (SpectraMAX 340, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Virus challenge

Since mice are irregularly susceptible to genital infection with HSV-1 unless they are synchronized into diestrous, mice were injected subcutaneously with 2 mg of Depo-Provera (medroxyprogesterone) (Pharmacia and Upjohn, Kalamazoo, MI) to synchronize the ovarian cycle.24,25 Five days later each mouse was anesthetized with avertin and infected intravaginally with 106 PFU of HSV-1 McKrae strain. Every 24 h a genital lavage specimen (washing with 200 µl PBS) was collected for viral titration and cytokine analysis. Mice were monitored daily for clinical disease and pathology and graded according to the following: (0) no apparent infection; (1) mild inflammation of the external genitalia; (2) redness and swelling of external genitals; (3) severe redness, inflammation, and genital ulceration with loss of hair; (4) hind limb paralysis; (5) death.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed by using a 2-tailed, unpaired, unequal variance student’s t test, and p < 0.05 were deemed significant.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant RO1 AI 4646 201.

Abbreviations

- ABTS

2,2′-Azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) diammonium salt

- CTL

cytotoxic T lymphocyte

- DC

dendritic cell

- gB

glycoprotein B

- HSV-1

herpes simplex virus-1

- Hsp70

heat-shock protein 70

- IFNγ

interferon gamma

- i.d.

intradermal

- i.n.

intranasal

- i.p.

intraperitoneal

- IPTG

isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactoside

- LCMV

lymphocytic choreomeningitis virus

- ON

overnight

- PFU

plaque forming units

- RT

room temperature

- s.c.

subcutaneous

References

- 1.Koelle DM. Vaccines for herpes simplex virus infections. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2006;7:136–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koelle DM, Corey L. Recent progress in herpes simplex virus immunobiology and vaccine research. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16:96–113. doi: 10.1128/CMR.16.1.96-113.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sin J, Kim JJ, Pachuk C, Satishchandran C, Weiner DB. DNA vaccines encoding interleukin-8 and RANTES enhance antigen-specific Th1-type CD4(+) T-cell-mediated protective immunity against herpes simplex virus type 2 in vivo. J Virol. 2000;74:11173–11180. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.23.11173-11180.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sin JI, Kim JJ, Arnold RL, Shroff KE, McCallus D, Pachuk C, McElhiney SP, Wolf MW, Pompa-de Bruin SJ, Higgins TJ, Ciccarelli RB, Weiner DB. IL-12 gene as a DNA vaccine adjuvant in a herpes mouse model: IL-12 enhances Th1-type CD4+ T cell-mediated protective immunity against herpes simplex virus-2 challenge. J Immunol. 1999;162:2912–2921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eo SK, Lee S, Kumaraguru U, Rouse BT. Immunopotentiation of DNA vaccine against herpes simplex virus via co-delivery of plasmid DNA expressing CCR7 ligands. Vaccine. 2001;19:4685–4693. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(01)00241-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gierynska M, Kumaraguru U, Eo SK, Lee S, Krieg A, Rouse BT. Induction of CD8 T-cell-specific systemic and mucosal immunity against herpes simplex virus with CpG-peptide complexes. J Virol. 2002;76:6568–6576. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.13.6568-6576.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gallichan WS, Woolstencroft RN, Guarasci T, McCluskie MJ, Davis HL, Rosenthal KL. Intranasal immunization with CpG oligodeoxynucleotides as an adjuvant dramatically increases IgA and protection against herpes simplex virus-2 in the genital tract. J Immunol. 2001;166:3451–3457. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.5.3451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumaraguru U, Gierynska M, Norman S, Bruce BD, Rouse BT. Immunization with chaperone-peptide complex induces low-avidity cytotoxic T lymphocytes providing transient protection against herpes simplex virus infection. J Virol. 2002;76:136–141. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.1.136-141.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumaraguru U, Suvas S, Biswas PS, Azkur AK, Rouse BT. Concomitant helper response rescues otherwise low avidity CD8+ memory CTLs to become efficient effectors in vivo. J Immunol. 2004;172:3719–3724. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.6.3719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pack CD, Kumaraguru U, Suvas S, Rouse BT. Heat-shock protein 70 acts as an effective adjuvant in neonatal mice and confers protection against challenge with herpes simplex virus. Vaccine. 2005;23:3526–3534. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.01.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Willey DE, Cantin EM, Hill LR, Moss B, Notkins AL, Openshaw H. Herpes simplex virus type 1-vaccinia virus recombinant expressing glycoprotein B: protection from acute and latent infection. J Infect Dis. 1988;158:1382–1386. doi: 10.1093/infdis/158.6.1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Binder RJ, Anderson KM, Basu S, Srivastava PK. Cutting edge: heat shock protein gp96 induces maturation and migration of CD11c+ cells in vivo. J Immunol. 2000;165:6029–6035. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.11.6029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Asea A, Kraeft SK, Kurt Jones EA, Stevenson MA, Chen LB, Finberg RW, Koo GC, Calderwood SK. HSP70 stimulates cytokine production through a CD14-dependant pathway, demonstrating its dual role as a chaperone and cytokine. Nat Med. 2000;6:435–442. doi: 10.1038/74697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Srivastava P. Roles of heat-shock proteins in innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:185–194. doi: 10.1038/nri749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Y, Kelly CG, Singh M, McGowan EG, Carrara AS, Bergmeier LA, Lehner T. Stimulation of Th1-polarizing cytokines, C-C chemokines, maturation of dendritic cells, and adjuvant function by the peptide binding fragment of heat shock protein 70. J Immunol. 2002;169:2422–2429. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.5.2422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Y, Kelly CG, Karttunen JT, Whittall T, Lehner PJ, Duncan L, MacAry P, Younson JS, Singh M, Oehlmann W, Cheng G, Bergmeier L, Lehner T. CD40 is a cellular receptor mediating mycobacterial heat shock protein 70 stimulation of CC-chemokines. Immunity. 2001;15:971–983. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00242-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parr MB, Parr EL. Vaginal immunity in the HSV-2 mouse model. Int Rev Immunol. 2003;22:43–63. doi: 10.1080/08830180305228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuklin NA, Daheshia M, Chun S, Rouse BT. Role of mucosal immunity in herpes simplex virus infection. J Immunol. 1998;160:5998–6003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hiroi T, Yanagita M, Ohta N, Sakaue G, Kiyono H. IL-15 and IL-15 receptor selectively regulate differentiation of common mucosal immune system-independent B-1 cells for IgA responses. J Immunol. 2000;165:4329–4337. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.8.4329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stanberry LR, Spruance SL, Cunningham AL, Bernstein DI, Mindel A, Sacks S, Tyring S, Aoki FY, Slaoui M, Denis M, Vandepapeliere P, Dubin G. Glycoprotein-D-adjuvant vaccine to prevent genital herpes. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1652–1661. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Drew MD, Estrada-Correa A, Underdown BJ, McDermott MR. Vaccination by cholera toxin conjugated to a herpes simplex virus type 2 glycoprotein D peptide. J Gen Virol. 1992;73:2357–2366. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-9-2357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sajic D, Ashkar AA, Patrick AJ, McCluskie MJ, Davis HL, Levine KL, Holl R, Rosenthal KL. Parameters of CpG oligodeoxynucleotide-induced protection against intravaginal HSV-2 challenge. J Med Virol. 2003;71:561–568. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lehner T, Bergmeier LA, Wang Y, Tao L, Sing M, Spallek R, van der Zee R. Heat shock proteins generate beta-chemokines which function as innate adjuvants enhancing adaptive immunity. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:594–603. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200002)30:2<594::AID-IMMU594>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaushic C, Ashkar AA, Reid LA, Rosenthal KL. Progesterone increases susceptibility and decreases immune responses to genital herpes infection. J Virol. 2003;77:4558–4565. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.8.4558-4565.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gillgrass AE, Ashkar AA, Rosenthal KL, Kaushic C. Prolonged exposure to progesterone prevents induction of protective mucosal responses following intravaginal immunization with attenuated herpes simplex virus type 2. J Virol. 2003;77:9845–9851. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.18.9845-9851.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Milligan GN, Bernstein DI. Interferon-gamma enhances resolution of herpes simplex virus type 2 infection of the murine genital tract. Virology. 1997;229:259–268. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adler H, Beland JL, Del-Pan NC, Kobzik L, Sobel RA, Rimm IJ. In the absence of T cells, natural killer cells protect from mortality due to HSV-1 encephalitis. J Neuroimmunol. 1999;93:208–213. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(98)00236-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ciupitu AM, Petersson M, O’Donnell CL, Williams K, Jindal S, Kiessling R, Welsh RM. Immunization with a lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus peptide mixed with heat shock protein 70 results in protective antiviral immunity and specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1998;187:685–691. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.5.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eo SK, Gierynska M, Kamar AA, Rouse BT. Prime-boost immunization with DNA vaccine: mucosal route of administration changes the rules. J Immunol. 2001;166:5473–5479. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.9.5473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Legge KL, Braciale TJ. Accelerated migration of respiratory dendritic cells to the regional lymph nodes is limited to the early phase of pulmonary infection. Immunity. 2003;18:265–277. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00023-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hunt C, Calderwood S. Characterization and sequence of a mouse hsp70 gene and its expression in mouse cell lines. Gene. 1990;87:199–204. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90302-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jindal S, Murray P, Rosenberg S, Young RA, Williams KP. Human stress protein hsp70: overexpression in E. coli, purification and characterization. Biotechnology (NY) 1995;13:1105–1109. doi: 10.1038/nbt1095-1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]