Abstract

UVB induced DNA damage is the major aetiological agent in NMSC development, but mounting evidence suggests a role for human papillomaviruses (HPV) from genus beta, including HPV 5 and HPV 8, in the development of NMSC on sun exposed body sites. We have previously shown that UVB activates Bak, an apoptogenic mitochondrial factor that, following an apoptotic stimulus, undergoes a conformational change that leads to pore formation in the mitochondrial membrane that releases apoptotic factors. The HPV E6 protein effectively inhibits UVB-induced apoptosis and targets Bak for proteolytic degradation. We have now identified the regions of the HPV5 E6 that are required to mediate Bak proteolysis and contribute toward the antiapoptotic activity of the protein. Interestingly, while wild-type HPV5 E6 does not bind or target p53 for proteolysis, we have isolated specific HPV5 E6 mutants that switch target specificity from Bak to p53 in a p53 codon 72 isoform-dependent manner. Furthermore, we demonstrate that the ability of wild-type HPV5 E6 to target Bak or specific E6 mutants to target p53 for proteolysis is not dependent on the E6-AP ubiquitin ligase.

Keywords: skin cancer, HPV, Bak, E6, UV, light

Chronic exposure to solar UV irradiation has been identified as the primary causative agent in the development of nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC).1 The formation of “sunburn cells” frequently observed in epidermis treated with UVB display apoptotic characteristic such as condensed nuclei,2,3 and the response to UVB radiation is in part dependent upon the expression of p53.4 This p53-driven response, often termed “cellular proofreading”, eliminates rather than repairs severely damaged cells, however p53-independent pathways have also been described.5-7 However, studies indicate that Li Fraumeni patients, who have only one copy of p53, and patients with regions of mutated p53 on sun-exposed sites, are not predisposed to tumour development8,9 indicating that p53-independent mechanisms also play an important role in eliminating damaged cells.

Studies on Epidermodysplasia Verruciformis (EV) patients have identified a link between extensive wart infection and the development of skin tumours on sun-exposed sites.10 Epidemiological studies also invoke a role for HPV in NMSC development in both immunocompromised organ transplant recipients and immunocompetent individuals.11,12 There is increasing evidence that β-HPV types facilitate the persistence of DNA-damaged cells within the epithelium, following UVB-exposure, chiefly through interfering with DNA damage responses and inhibiting apoptotic pathways, reviewed by Akgül et al.13

The Bak protein is a key apoptogenic factor located in the outer mitochondrial membrane.14 Following UV exposure, Bak is activated and stabilized in a p53-independent manner7 by BH3 domain-containing proteins.15,16 Bak activation involves a change in conformation at the N-terminus of the prote in17 leading to Bak multimerization,18-20 that is believed to form pores in the mitochondrial membrane that allows the release of cytochrome c and other proapoptotic factors into the cytoplasm.21 We have previously shown that the HPV E6 protein of β-HPV types targets Bak for ubiquitin mediated degradation,7 an E6 activity that prevents release of proapoptotic mitochondrial factors thereby maintaining mitochondrial integrity and function.22 In marked difference to anogenital HPVs, β-type viruses such as HPV8 do not target p53 for proteolysis and do not interact with the E6-AP ubiquitin ligase utilized by anogenital HPV E6 proteins to signal p53 destruction.23 Analysis of NMSC biopsies has also revealed that HPV-negative tumours have both a high apoptotic and proliferation rate compared to HPV-positive tumours that are also highly proliferative, but in contrast have a low apoptotic rate, in addition to significantly reduced levels of Bak.24

Recently the solution structure of the HPV16 E6 protein has been determined from which a model of the full length protein has been proposed. These studies suggested that the protein is divided into two similar domains termed E6N and E6C, which each consist of a α/β zinc binding fold. Each of these domains contains a three-stranded β-sheet (S1, S2 and S3) and two short helices (H1 and H2). Two loops (L1 and L2) connect S1 to H1 and H1 and H2 to a further helix H3, respectively.25 Analysis of the predicted surface residues of anogenital HPV E6 proteins has revealed that these are more hydrophilic, in comparison to cutaneous HPV E6 proteins, which are more hydrophobic. This suggests that E6 proteins expressed by anogenital and cutaneous HPVs are likely to target different cellular proteins, resulting in varying effects on, for example, cell cycle regulation and apoptosis. This structural information suggests that many of the previous studies utilising E6 mutants might have indirectly altered its function in assays, including p53 degradation studies performed in reticulocyte lysates. Using a ligase-dead E6-AP, these authors showed different E6 surface residues were involved in the ability of E6 to promote p53 degradation in vivo to those previously implicated.

We have undertaken studies to determine the regions of the HPV5 E6 protein that are important for the antiapoptotic activity of the protein and to investigate the molecular basis for cutaneous E6 proteins targeting only Bak and not p53 for proteolysis. Our results demonstrate that the E6 antiapoptotic activity is sensitive to point mutations in the protein that affect the ability of E6 to inhibit Bak activation and target the protein for degradation. Interestingly, specific HPV5 E6 mutants that had lost activity toward Bak were able to target p53 for proteolysis that was dependent on the p53 codon 72 isoform status. In addition, we provide evidence that the proteolytic targeting of Bak by HPV5 E6, or p53 by the HPV5 E6 mutants, is independent of the E6-AP ubiquitin ligase.

Material and methods

Cloning

HPV5 E6, p53-Pro or p53-Arg were each cloned into a pcDNA3.1 vector containing HA or FLAG tags.26 E6 sequences were amplified by PCR from the viral and human genome using a Pfu PCR system (Promega, Southampton, UK). Primers (Sigma, Gillingham, UK) were designed with 5′ BamHI and 3′ XhoI restriction sites and amplified sequences were ligated into digested pcDNA3.1 (New England Biolabs, Hitchin, UK). Similarly, E6 sequences were amplified by PCR and inserted between the BamHI and EcoRI sites for pGEX2T to generate GST fusion constructs. All clones were confirmed by direct sequencing using the ABI Big Dye Terminator v3.0 cycle sequencing kit. Site-directed mutagenesis of HPV5 E6 was performed using the QuickChange system (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The pGEM-E6-AP plasmid used for in vitro translation of full length E6-AP was a gift from M. Ditzel and the HA-tagged Bak construct was from T. Chittenden.

Cell culture and transfections

HT1080, Saos2, C33I and MEF cells were maintained at 37°C/10% CO2 in Dulbecco’s modified MEM (DMEM), supplemented with 10% FCS and l-glutamine. Stable cell lines expressing HPV5 E6 mutants (derived from HT1080) were selected using G418. Protein degradation assays were performed by transfecting Saos2 cells with HPV5 E6-HA mutants with either pcDNA 3.1-p53-Pro, p53-Arg or Bak and harvesting after 24 hr. MG132 (10 μM) was added 4 hr posttransfection to inhibit proteaseome activity.

Flow cytometry

Cell lines stably expressing HPV5 E6-HA mutants (derived from HT1080) were UVB irradiated at 1 m J cm−2 and harvested after 24 hr as described. Apoptosis assay cells were removed using trypsin and handled on ice. Samples were incubated at room temperature for 15 min with 1× Annexin buffer containing 1:100 anti-Annexin V-Alexa 647 (Cambridge Biosciences, Cambridge, UK). Five microliter iodide was added to each sample and samples maintained on ice. To quantify levels of activated Bak and to measure apoptosis, samples were analyzed by flow cytometry (LSR, Becton Dickinson, Oxford, UK) where detection of Annexin V was used as a marker for early apoptotic cells, and double labeled Annexin V/propidium iodide cells represented late apoptotic cells.

Western blotting

Saos2 cells were were washed once with ice-cold PBS and lysed on ice for 20 min in RIPA lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 1% Nonidet-P40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1% SDS) supplemented with 1× cocktail protease inhibitors (Roche). The resultant extracts were sonicated on ice and the protein concentration determined using Bio-Rad Protein Assay (Bio-Rad). Extracts were diluted in 5× Laemmli buffer and boiled at 100°C for 3 min. Ten microgram protein from each sample was separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred overnight to a PVDF membrane according to standard methods. Membranes were probed with primary antibodies to p53 DO1 1:1000 (Cancer Research UK), HA-tag 1:1000 (Covance, Harrogate, UK) and GAPDH 1:4000 (AbCam) and rabbit anti-mouse-hrp conjugate 1:1000 (Dako) in PBS/0.1% Tween 20/10% skimmed milk. Proteins were developed using an ECL+ detection kit (GE Healthcare, Chalfont St. Giles, UK).

GST-pulldown

C33-I cells were cotransfected with pBC-E6AP C843A and one of pcDNA 3.1-5E6-HA, 18E6-HA or vector alone. After 30 hr, cells were rinsed in ice-cold PBS and lysed on ice for 20 min in lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris pH 8, 1% Nonidet-P40, 2 mM dithiothreitol) supplemented with 1× cocktail protease inhibitors (Roche). Cell lysates was cleared by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 20 min at 4°C, and incubated with 100 μl of a 50% slurry of glutathione-agarose beads in binding buffer (as lysis buffer, except 0.1% Nonidet-P40) overnight at 4°C with rotation. Beads were washed three times with 1 ml ice-cold PBS, boiled in 50 μl 2× Laemmli buffer for 5 min and separated by SDS-PAGE. GST fusion proteins were produced in bacteria and isolated using glutathione agarose beads by standard techniques. HPV E6 genes were cloned into the pGEX2T vector. In vitro translated proteins were produced using a coupled transcription/translation system (Promega) and radiolabeled with 35S cysteine. Bound proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE, then imaged and quantified using a Storm phosphoimager and ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics, GE Healthcare, Chalfont St. Giles, UK). Westerns blots were performed as described above.

Results

Identification of regions of HPV5 E6 involved in Bak degradation

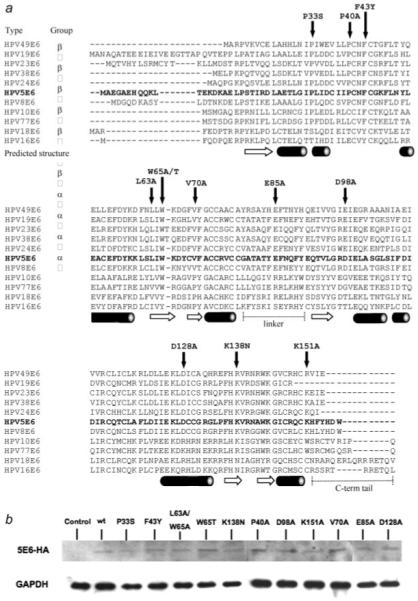

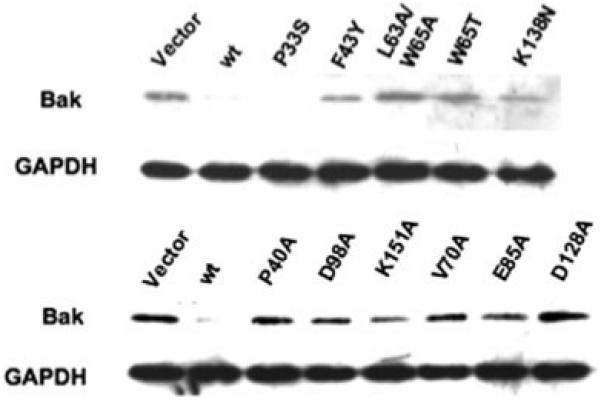

At present, little is known of the structure/function relationships of the cutaneous E6 proteins and the regions of the molecule that are important in interacting with cellular targets. We hypothesized that specific residues in HPV5 E6 may direct the protein to target Bak but not p53 for proteolysis. To ascertain regions of the E6 protein involved in the degradation of Bak, point mutants were induced across multiple domains of the HPV5 E6 protein (Figure 1a). Three different classes of mutants were generated in residues that: (i) were conserved amongst α and β cutaneous viruses that were different from anogenital E6 proteins, such as P33S; (ii) were conserved only amongst β-types, for example P40A or D98A and (iii) where an amino acid in a β-type was changed to that found in anogenital α-types, such as K138N. These mutations were constructed before the structural information of E6 was available, and some of the mutated residues are not predicted to be on the surface. This includes amino acid position 65, where mutation W65A may disrupt the fold of the E6 N-terminal domain. Similarly, L63A may also disrupt the protein fold, but alternatively could make the protein less stable, whereas V70A may have a conserved structure. However, expression of the mutants was confirmed in HT1080 cells using HA-tagged proteins, which showed that none of the mutant proteins were inherently unstable (Fig. 1b). Three of the HPV5 E6 mutations changed charged residues to alanine thereby altering the overall net charge of wild-type HPV5 E6 that is calculated to be −4, with a concomitant alteration in the theoretical pI from 5.56 of the wild type protein to 5.80 for the E85A, D98A and D128A mutants (calculated using the ExPASY ProtParam tool). Interestingly, the E6 model of Nomine et al.,25 predicts that β-type HPVs such as HPV5 have a negative surface charge, in marked contrast to α-type viruses such as HPV16 E6, and hence the mutants generated here would not be predicted to affect the overall negatively charged nature of the HPV5 E6 surface. Following UVB exposure, Bak undergoes an N-terminal conformational change to a primed or active form, which can then multimerize and facilitate pore formation in the outer mitochondrial membrane, leading to the release of various proapoptotic factors.16 To investigate whether any of the point mutants affected the ability of E6 to promote Bak degradation, we performed Western blotting of Bak from cells transfected with either the wild-type HPV5 E6 or the individual point mutants. These experiments indicated that of all the mutants tested, only P33S retained the capacity to promote Bak proteolysis to a similar degree to the wild-type HPV5 E6 protein. All the other mutants tested displayed an impaired ability to promote Bak proteolysis, implying that this E6 function is very sensitive to small point mutations in different parts of the molecule (Fig. 2). Although cutaneous HPV E6 can promote Bak proteolysis in human keratinocytes, the cells used in these experiments are not the natural host for the virus, however, previous studies have shown that the ability of E6 to target the apoptotic machinery is not dependent upon cell type or p53 status.7,27

Figure 1.

Location of point mutants in conserved regions of HPV 5 E6. (a) Sequence alignment of the α and β-HPV types showing point mutations in conserved regions of the protein. The predicted secondary structure is shown below the primary amino acid sequence where cylinders represent α-helix and arrows β-sheet, with the N- and C-terminal domains separated by a linker (derived from Ref. 25). (b) Detection of HA-tagged HPV5 E6 mutants in HT1080 cells by Western blot with HA antibody indicated that each of the mutants was able to express a stable E6 protein. The blot is representative of cell lines derived from two separate transfections. Extended detection times both contribute toward the high background of the blot and suggest that the E6 proteins are expressed at low levels.

Figure 2.

Effect of HPV5 E6 mutants on Bak degradation. Saos2 cells were transfected with an HPV5 E6 plasmid or the specified mutant together with HA-tagged Bak. Empty vector that lacked E6 sequences was used as a control. Mutant P33S was able to promote Bak degradation in similar fashion to the wild-type HPV5 E6, however, all other mutants showed some degree of impairment in the ability of the protein to promote Bak degradation.

Mutations in HPV5 E6 can influence target specificity

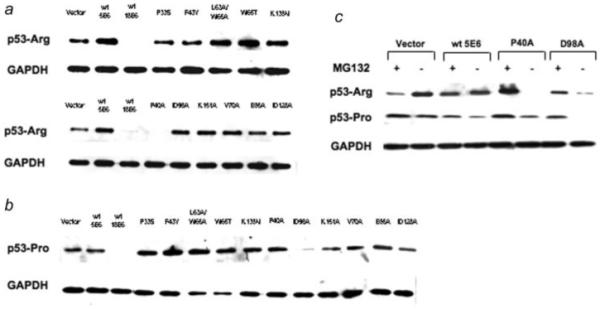

Having shown that the integrity of multiple regions of HPV5 E6 is required in order to target Bak for proteolysis, we were interested to determine whether any of the mutations affected the ability of E6 to target other proteins for degradation, in particular p53, as previous studies had shown that only anogential but not cutaneous HPV E6 proteins target p53 for proteolysis. As part of this analysis we compared the degradation profile of both the Arg and Pro variants of p53 against the HPV5 E6 mutants, as previous work had shown that HPV18 E6 may affect differently the proteolysis of p53 isoforms. The HPV 18 E6 protein, which signals strongly the degradation p53, was used as a control. Wild-type HPV5 E6 did not target either p53Arg or Pro for ubiquitin-mediated degradation, as previously reported. Strikingly however, the P40A mutant displayed a similar degradation profile to HPV18 E6, in that it strongly degraded the p53Arg isoform, but surprisingly failed to promote proteolysis of the p53 Pro isoform (Fig. 3a). All the other mutants had little effect on p53Arg, displaying a similar phenotype to the wild-type. Conversely, the D98A mutant caused a reduction of p53Pro levels, but this was not as strong as the HPV18 E6 activity (Fig. 3b). Interestingly the P40A and D98A mutants, while able to each promote the degradation of one p53 isoform, were unable to promote the degradation of the other p53 form, suggesting that the p53 conformation also plays a role in determining the target specificity of the mutants. Moreover, the mutants P40A and D98A had lost the capacity to promote Bak degradation, indicating a switch in target specificity caused by mutation of these residues. The addition of the proteosome inhibitor MG132 caused a rescue of P40A and D98A associated degradation of p53Arg and Pro forms respectively by the two E6 mutants, and had no effect on the wild-type HPV5 E6 which did not target p53 for degradation (Fig. 3c).

Figure 3.

Specific HPV5 E6 mutants are able to target p53 for degradation. Saos2 cells were transfected with HPV5 E6 or mutants plasmids together with either the p53-Arg (a) or p53-Pro (b) variants. While the wild-type HPV5 E6 was unable to promote p53 degradation and HPV18 E6 is able to signal proteolysis of both isoforms, P40A and D98A both acquired an HPV18-like phenotype by being able to promote p53-Arg [for P40A, see (a)] or p53-Pro (for D98A, see (b) degradation, respectively. (c) As in (b) above, except that incubation of the cells with 10 μM of the proteasome inhibitor MG132 prior to harvesting rescued p53-Arg and p53-Pro from degradation by P40A or D98A, respectively.

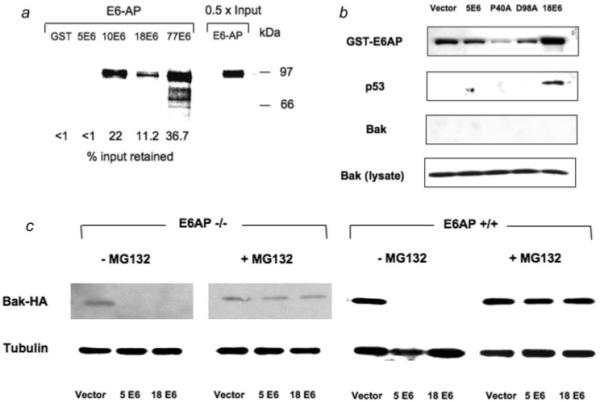

HPV5 E6-mediated Bak degradation does not require E6AP

The ability of anogenital E6 proteins to target p53, and possibly Bak, for ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis requires the E3 ubiquitin ligase E6AP.28-32 We therefore investigated whether HPV5 E6 required E6AP to promote Bak degradation in our system. First, we tested whether E6 proteins of cutaneous HPV types that can promote Bak degradation interacted with E6AP in pull-down assays using GST-E6 and in vitro translated E6AP. HPV5 E6 differed from the other E6 proteins tested in that it failed to bind GST-E6AP (Fig. 4a), observations in agreement with previous studies using HPV8 E6,23 while HPV10 and HPV77 E6 proteins bound more E6AP than HPV18 E6 in these assays. Thus, it appears that the ability of a particular HPV E6 type to interact with E6-AP in vitro does not imply that that E6 type may promote p53 degradation. To extend these complex formation assays, a GST-E6AP C843A construct that was devoid of ubiquitin ligase activity,25 was used in an in vivo pull-down assay in combination with HPV5 and 18 E6 to further investigate potential protein interactions. The use of the ligase-dead E6-AP allows analysis of the E6:E6-AP:p53 complex to be performed more readily. The HPV18 E6 protein interacted with p53 in the presence of GST-E6AP as expected, however neither the HPV5 E6 P40A nor D98A mutants, that had acquired the ability to promote p53 degradation, pulled down p53 using the ligase-dead GST-E6AP as bait. Additionally, none of the E6 proteins were able to pull down Bak under these experimental conditions (Fig. 4b).

Figure 4.

HPV5 E6-mediated Bak degradation does not require E6AP. (a) HPV5 E6 does not interact with E6AP in vitro. Equal amounts (2 μg) of either GST or GST-E6 proteins immobilized on GST agarose beads (not shown) were incubated with 35S labeled E6-AP. After washing the beads the bound radiolabeled E6-AP was eluted, fractionated by SDS-PAGE and quantified by phosphorimaging. While HPV5 E6 showed no interaction with E6-AP under these conditions, E6 proteins from other cutaneous HPVs (HPV10 and 77) bound E6-AP. (b) HPV5 E6 does not interact with E6-AP in vivo. C33-I cells that express high levels of p53 were transfected with a ligase dead GST-E6AP C843A expressing plasmid together with an HPV E6 and Bak plasmids as indicated. Cells were harvested and protein extracts incubated with GST agarose. After washing, bound proteins were eluted and subjected to western blotting to determine whether p53 or Bak were bound. As expected, in cells containing HPV18 E6 p53 was recovered from cells by the GST-E6AP construct. Neither wild-type HPV5 E6 or the P40A or D98A mutants that were able to promote the degradation of specific p53 isoforms were able to direct the binding of p53 to E6-AP under these conditions. (c) E6AP−/−33 or E6AP+/+ MEFs were transfected with either HPV5 or HPV18 E6 plasmids together with HA-tagged Bak construct and protein extracts were western blotted to investigate Bak levels. Degradation of Bak occurred in both E6AP−/− and E6AP+/+ cells that were transfected with either HPV5 or HPV18 E6 plasmids. Inclusion of the proteasome inhibitor MG132 restored Bak levels in E6AP−/− cells suggesting that an ubiquitin ligase other than E6-AP was involved in Bak degradation by the E6 proteins.

To test further the requirement of E6-AP to promote Bak proteolysis we performed similar experiments to those described earlier in Saos2 cells in E6AP−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Western blotting of protein extracts from cells transfected with either HPV 5 and 18 E6 constructs showed that either protein was able to promote Bak degradation in the absence of E6AP, and that this degradation was rescued by MG132 addition (Fig. 4c) indicating a proteasomal involvement. These data together suggest that HPV5 E6 recruits a different ubiquitin ligase to degrade Bak, and that while HPV5 E6 target specificity can be changed so that the protein now promotes p53 proteolysis, E6AP is not likely to be involved in this activity.

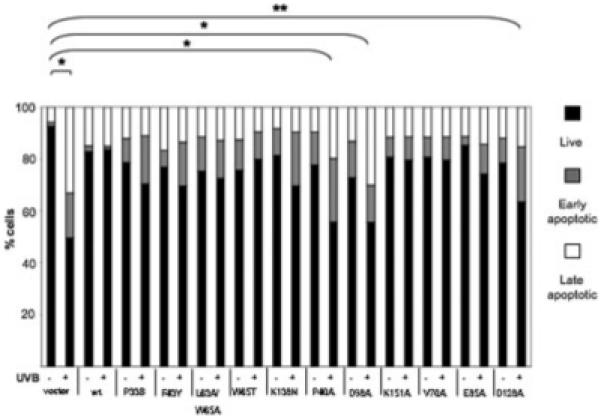

Mutations in HPV 5 E6 inhibit the antiapoptotic properties of the protein

A critical step in the pathogenesis of HPV is thought to be the prevention of host cell elimination following genotoxic stress, such as UVB exposure, and the expression of the E6 protein is fundamental in this process [reviewed in Ref. 13]. We have previously reported that at doses of UVB that are sufficient to initiate apoptosis in HT1080 cells, the HPV5 E6 protein is sufficient to overcome the apoptotic response. In stable cell lines expressing the pcDNA vector, exposure to UVB, caused a 38% reduction in the live cell population after 24 hr, but no reduction was observed in cells expressing HPV5 E6. We examined whether specific mutations in the E6 protein, which affected both Bak degradation and activation, also affected the ability of the protein to prevent apoptosis in UVB-exposed cells in similar assays (Fig. 5). Mutants P40A, D98A, V70A, D128A and K138N differed from the wild-type (p = < 0.02) in that they partially lost the ability to prevent apoptosis following UVB exposure, with a reduction in the live cell population by 22, 17, both 15 and 11%, respectively, such that the cells expressing the P40A and D98A mutants had a live cell fraction similar to cells transfected with vector alone. The other mutants exhibited a varying propensity to inhibit apoptosis, with the percentage of live cells remaining similar before and after UVB exposure, but at levels lower than the wild-type HPV5 E6. These mutants also differed from the wild-type in that there was an increase in the number of cells entering early apoptosis following UVB exposure, suggesting a defect in activity. It is interesting that the majority of the mutants showed some degree of apoptotic inhibition, despite variations in their ability to promote Bak degradation. The P40A, V70A, L63A/W65A, D98A and D128A mutants that had lost completely all activity toward Bak yet still partially inhibited apoptosis, suggesting that there may be further proapoptotic targets of E6 involved in UVB-induced apoptosis.

Figure 5.

HPV5 E6 mutations inhibit antiapoptotic activity. Stable cell lines expressing the HPV 5 E6 mutants (derived from HT1080) were exposed to 1 m J cm-2 UVB (+) or not irradiated (−) and harvested 24 hr later and the levels of apoptosis analyzed by FACS. As reported previously, wild-type HPV5 E6 inhibited UVB-induced apoptosis. The HPV5 E6 mutants showed varying degrees of apoptotic inhibition. Apoptotic levels in cells expressing either the P40A or D98A mutant conferred the least protection from apoptosis. Experiments were repeated three times for statistical analysis. *p ≤ 0.02, ** p ≤ 0.05.

Discussion

In this article we have identified a number of mutations in the HPV5 E6 protein that influence its ability to promote Bak degradation and inhibit apoptosis. In addition, two gain of function mutants were isolated that were able to promote p53 degradation. The activities of the mutants can be divided broadly into two distinct classes those that: (i) had impaired ability to promote Bak proteolysis and (ii) those that had lost activity toward Bak but gained the ability to promote p53 degradation. The overall results are summarized in Table I. The diverse locations of these mutations within E6, some of which exhibit similar characteristics in terms of the ability of the E6 protein to promote Bak degradation, indicates that multiple regions of the protein are critical in the interaction with specific cellular targets. The antiapoptotic activity of the protein was also found to be sensitive to mutations introduced throughout the molecule, irrespective of whether Bak degradation was affected. At present, the functional roles of the cutaneous E6 domains remain to be defined fully, so it is possible that these mutations may affect protein-protein interactions by variations in charge and hydrophobicity or by structural alterations, either directly or indirectly. This work has demonstrated the significance of the residues in mutants P40A and D98A, that are predicted to be at the surface according to the current model of E6 structure,25 in that these were able to degrade either the Arg and Pro forms of p53, respectively. Both P40A and D98A mutants belong to class (ii) in our nomenclature, that is, the positions were conserved only amongst β-types. An exposed nature of the amino acids at positions 40 and 98 may imply that both loops are important in the direct interaction of E6 with p53, or that one or both residues have a structural role in maintaining the integrity of a separate p53 binding domain. It is possible that both mutations could cause significant structural change, with the replacement of a proline, which may facilitate loop L2 turn formation in the zinc binding site, and a charged aspartic acid, to an uncharged alanine in residues 40 and 98, respectively. Interestingly, the P40A and D98A mutants also showed the greatest defect in the ability to inhibit apoptosis, suggesting that the ability of E6 to target Bak but not p53 was more important for the antiapoptotic activity in these assays.

TABLE I.

SUMMARY OF HPV5 E6 MUTANT ACTIVITY

| Promotes Bak proteolysis | Promotes p53 degradation | Inhibition of apoptosis | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | +++ | N | +++ |

| P33S | +++ | N | ++ |

| F43Y | + | N | ++ |

| L63A/W65A | − | N | ++ |

| W65T | + | N | ++ |

| K138N | + | N | ++ |

| P40A | − | Y (Arg) | + |

| D98A | − | Y (Pro) | + |

| K151A | + | N | ++ |

| V70A | − | N | ++ |

| E85A | + | N | ++ |

| D128A | − | N | + |

When compared to the wild-type protein only the P33S mutant was able to promote Bak degradation to a comparable degree, all other mutants showed an impaired Bak degradation activity. We have used an arbitrary classification to indicate broadly the relative activities for each of the activities investigated: +++ = strong, ++ = intermediate activity, + = weak activity, − = no detectable activity. Surprisingly, two mutants displayed a gain of function in that they were able to promote p53 degradation. The p53 degradation was dependent upon the p53 isoform, whereby P40A was able to promote p53-Arg but not p53-Pro degradation, and conversely D98A promoted p53-Pro but not p53-Arg degradation. All mutants were not as effective as the wild-type protein at inhibiting apoptosis in response to UVB, with mutants P40A, D98A and D128A having the least activity.

The switch in target specificity from Bak to p53, caused by a single amino acid change at two different positions, suggests that this phenotype could easily occur naturally. However, variants of HPV 5 E6 that can degrade p53 have not been described so far,34 suggesting that the removal of p53 from the host cell is not essential for the survival of the virus and that Bak, which initiates apoptosis at the mitochondria, may be a more significant target in this respect. It is also noteworthy that a proportion of activated p53 also translocates to the mitochondria during apoptosis where it interacts with Bak. Thus, by targeting Bak for proteolysis the virus also eliminates this apoptotic p53 activity.35 Recently the crystal structure of Bak has been solved revealing that the BH3 domain, that is required for apoptosis, is occluded in the structure.36 Additionally, following DNA damage, it was reported that Bak undergoes a conformational change that temporarily exposes the BH3 domain that is then inserted into a groove of another Bak monomer that was essential to initiate Bak oligomerization.37 Although early reports implicated the extreme C-terminal region of Bak as being important of association with HPV18 E6 and that the BH3 region was dispensable for the association.31 However, the fact that the ΔC Bak mutant used in these studies deletes the transmembrane domain of Bak that is required the mitochondrial localization of the protein, and as such would be inaccessible to E6, suggests that other more accessible regions of Bak mediate the association with E6. If HPV E6 proteins were to target Bak only after an apoptotic signal, then this would suggest that conformational changes in Bak may be important for E6 to recognize activated forms of Bak.

With respect to Bak proteolysis, we present strong evidence that a different ubiquitin ligase other than E6-AP can be used by HPV5 E6 to target Bak for destruction. We were unable to detect any interaction between HPV5 E6 and E6AP using GST pull-down assays in vitro, or in vivo using a ligase dead GST-E6AP, HPV5 E6 and Bak. We also showed that E6 was capable of promoting Bak degradation in the absence of E6AP in E6AP−/− MEFs. In addition, no E6-AP binding activity was noted for the P40A and D98A mutants that were able to target p53 for proteolysis. Interestingly, recent studies have also shown that in the absence of E6-AP, HPV16 or 18 E6 can still promote p53 proteolysis in a proteasome-dependent manner,38 suggesting that E6 proteins may interact with different ubiquitin ligases to target specific proteins.

Current evidence indicates that skin tumour development requires UV-induced mutations to occur and suggests that HPVs have a cofactorial role in this process, highlighted by EV and immunosuppressed patients, which cannot effectively clear the virus. It has already been demonstrated, in terms of potential tumour initiation, that HPV5 E6 interferes with the repair of UVB-induced thymine dimers.39 Our data show that amino acids from different regions of the HPV5 E6 make important contributions toward the inactivation of Bak and that these play a important role in the antiapoptotic activity of the protein. Further studies are required to identify the ubiquitin ligase other than E6-AP that can be used by HPV5 E6 to degrade Bak that will not only further our understanding of the role of β-HPVs in NMSC development, but may also represent a novel target for intervention in HPV-associated disease.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Professor A.L. Beaudet for the gift of the E6AP−/− MEFs and Dr. G. Trave for the GST-E6AP ligase-dead construct and helpful discussions regarding the impact of the mutations on the structure of HPV5 E6.

Grant sponsor: Cancer Research UK.

References

- 1.Karagas MR, Nelson HH, Sehr P, Waterboer T, Stukel TA, Andrew A, Green AC, Bavinck JN, Perry A, Spencer S, Rees JR, Mott LA, et al. Human papillomavirus infection and incidence of squamous cell and basal cell carcinomas of the skin. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:389–95. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwarz A, Bhardwaj R, Aragane Y, Mahnke K, Riemann H, Metze D, Luger TA, Schwarz T. Ultraviolet-B-induced apoptosis of keratinocytes: evidence for partial involvement of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in the formation of sunburn cells. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;104:922–7. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12606202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young AR. The sunburn cell. Photodermatology. 1987;4:127–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ziegler A, Jonason AS, Leffell DJ, Simon JA, Sharma HW, Kimmelman J, Remington L, Jacks T, Brash DE. Sunburn and p53 in the onset of skin cancer. Nature. 1994;372:773–6. doi: 10.1038/372773a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allday MJ, Inman GJ, Crawford DH, Farrell PJ. DNA damage in human B cells can induce apoptosis, proceeding from G1/S when p53 is transactivation competent and G2/M when it is transactivation defective. Embo J. 1995;14:4994–5005. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00182.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gniadecki R, Hansen M, Wulf HC. Two pathways for induction of apoptosis by ultraviolet radiation in cultured human keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 1997;109:163–9. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12319216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jackson S, Harwood C, Thomas M, Banks L, Storey A. Role of Bak in UV-induced apoptosis in skin cancer and abrogation by HPV E6 proteins. Genes Dev. 2000;14:3065–73. doi: 10.1101/gad.182100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malkin D, Li FP, Strong LC, Fraumeni JF, Nelson CE, Kim DH, Kassel J, Gryka MA, Bischoff FZ, Tainsky MA, Friend SH. Germ line p53 mutations in a familial syndrome of breast cancer, sarcomas, and other neoplasms. Science. 1990;250:1233–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1978757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ren ZP, Hedrum A, Ponten F, Nister M, Ahmadian A, Lundeberg J, Uhlen M, Ponten J. Human epidermal cancer and accompanying pre-cursors have identical p53 mutations different from p53 mutations in adjacent areas of clonally expanded non-neoplastic keratinocytes. Oncogene. 1996;12:765–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Termorshuizen F, Feltkamp MC, Struijk L, de Gruijl FR, Bavinck JN, van Loveren H. Sunlight exposure and (sero)prevalence of epidermodysplasia verruciformis-associated human papillomavirus. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122:1456–62. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.22617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harwood CA, Proby CM, McGregor JM, Sheaff MT, Leigh IM, Cerio R. Clinicopathologic features of skin cancer in organ transplant recipients: a retrospective case-control series. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:290–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harwood CA, Surentheran T, Sasieni P, Proby CM, Bordea C, Leigh IM, Wojnarowska F, Breuer J, McGregor JM. Increased risk of skin cancer associated with the presence of epidermodysplasia verruciformis human papillomavirus types in normal skin. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:949–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.05847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akgüul B, Cooke JC, Storey A. HPV-associated skin disease. J Pathol. 2006;208:165–75. doi: 10.1002/path.1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karbowski M, Norris KL, Cleland MM, Jeong SY, Youle RJ. Role of Bax and Bak in mitochondrial morphogenesis. Nature. 2006;443:658–62. doi: 10.1038/nature05111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Willis SN, Chen L, Dewson G, Wei A, Naik E, Fletcher JI, Adams JM, Huang DC. Proapoptotic Bak is sequestered by Mcl-1 and Bcl-xL, but not Bcl-2, until displaced by BH3-only proteins. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1294–305. doi: 10.1101/gad.1304105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Willis SN, Fletcher JI, Kaufmann T, van Delft MF, Chen L, Czabotar PE, Ierino H, Lee EF, Fairlie WD, Bouillet P, Strasser A, Kluck RM, et al. Apoptosis initiated when BH3 ligands engage multiple Bcl-2 homologs, not Bax or Bak. Science. 2007;315:856–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1133289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Griffiths GJ, Dubrez L, Morgan CP, Jones NA, Whitehouse J, Corfe BM, Dive C, Hickman JA. Cell damage-induced conformational changes of the pro-apoptotic protein Bak in vivo precede the onset of apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:903–14. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.5.903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Korsmeyer SJ, Wei MC, Saito M, Weiler S, Oh KJ, Schlesinger PH. Pro-apoptotic cascade activates BID, which oligomerizes BAK or BAX into pores that result in the release of cytochrome c. Cell Death Differ. 2000;7:1166–73. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wei MC, Lindsten T, Mootha VK, Weiler S, Gross A, Ashiya M, Thompson CB, Korsmeyer SJ. tBID, a membrane-targeted death ligand, oligomerizes BAK to release cytochrome c. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2060–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wei MC, Zong WX, Cheng EH, Lindsten T, Panoutsakopoulou V, Ross AJ, Roth KA, MacGregor GR, Thompson CB, Korsmeyer SJ. Proapoptotic BAX and BAK: a requisite gateway to mitochondrial dysfunction and death. Science. 2001;292:727–30. doi: 10.1126/science.1059108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hacker G, Weber A. BH3-only proteins trigger cytochrome c release, but how? Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;462:150–5. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2006.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leverrier S, Bergamaschi D, Ghali L, Ola A, Warnes G, Akgul B, Blight K, Garcia-Escudero R, Penna A, Eddaoudi A, Storey A. Role of HPV E6 proteins in preventing UVB-induced release of proapoptotic factors from the mitochondria. Apoptosis. 2007;12:549–60. doi: 10.1007/s10495-006-0004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steger G, Pfister H. In vitro expressed HPV 8 E6 protein does not bind p53. Arch Virol. 1992;125:355–60. doi: 10.1007/BF01309654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jackson S, Ghali L, Harwood C, Storey A. Reduced apoptotic levels in squamous but not basal cell carcinomas correlates with detection of cutaneous human papillomavirus. Br J Cancer. 2002;87:319–23. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nomine Y, Masson M, Charbonnier S, Zanier K, Ristriani T, Deryckere F, Sibler AP, Desplancq D, Atkinson RA, Weiss E, Orfanoudakis G, Kieffer B, et al. Structural and functional analysis of E6 oncoprotein: insights in the molecular pathways of human papillomavirus-mediated pathogenesis. Mol Cell. 2006;21:665–78. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giampieri S, Garcia-Escudero R, Green J, Storey A. Human papillomavirus type 77 E6 protein selectively inhibits p53-dependent transcription of proapoptotic genes following UV-B irradiation. Oncogene. 2004;23:5864–70. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jackson S, Storey A. E6 proteins from diverse cutaneous HPV types inhibit apoptosis in response to UV damage. Oncogene. 2000;19:592–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hengstermann A, Linares LK, Ciechanover A, Whitaker NJ, Scheffner M. Complete switch from Mdm2 to human papillomavirus E6-mediated degradation of p53 in cervical cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:1218–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.031470698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huibregtse JM, Scheffner M, Howley PM. A cellular protein mediates association of p53 with the E6 oncoprotein of human papillomavirus types 16 or 18. Embo J. 1991;10:4129–35. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04990.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scheffner M, Huibregtse JM, Vierstra RD, Howley PM. The HPV-16 E6 and E6-AP complex functions as a ubiquitin-protein ligase in the ubiquitination of p53. Cell. 1993;75:495–505. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90384-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomas M, Banks L. Inhibition of Bak-induced apoptosis by HPV-18 E6. Oncogene. 1998;17:2943–54. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomas M, Banks L. Human papillomavirus (HPV) E6 interactions with Bak are conserved amongst E6 proteins from high and low risk HPV types. J Gen Virol. 1999;80(Part 6):1513–7. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-6-1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang YH, Armstrong D, Albrecht U, Atkins CM, Noebels JL, Eichele G, Sweatt JD, Beaudet AL. Mutation of the Angelman ubiquitin ligase in mice causes increased cytoplasmic p53 and deficits of contextual learning and long-term potentiation. Neuron. 1998;21:799–811. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80596-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deau MC, Favre M, Jablonska S, Rueda LA, Orth G. Genetic heterogeneity of oncogenic human papillomavirus type 5 (HPV5) and phylogeny of HPV5 variants associated with epidermodysplasia verruciformis. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2918–26. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.11.2918-2926.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leu JI, Dumont P, Hafey M, Murphy ME, George DL. Mitochondrial p53 activates Bak and causes disruption of a Bak-Mcl1 complex. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:443–50. doi: 10.1038/ncb1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moldoveanu T, Liu Q, Tocilj A, Watson M, Shore G, Gehring K. The X-ray structure of a BAK homodimer reveals an inhibitory zinc binding site. Mol Cell. 2006;24:677–88. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dewson G, Kratina T, Sim HW, Puthalakath H, Adams JM, Colman PM, Kluck RM. To trigger apoptosis. Bak exposes its. BH3 domain and homodimerizes via. BH3:groove interactions. Mol Cell. 2008;30:369–80. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Massimi P, Shai A, Lambert P, Banks L. HPV E6 degradation of p53 and PDZ containing substrates in an E6AP null background. Oncogene. 2008;27:1800–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Giampieri S, Storey A. Repair of UV-induced thymine dimers is compromised in cells expressing the E6 protein from human papillomaviruses types 5 and 18. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:2203–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]