Abstract

Over the past decade, a class of small RNA molecules called microRNAs (miRNAs) has been shown to regulate gene expression at the post-transcription stage. While early work focused on the identification of miRNAs using a combination of experimental and computational techniques, subsequent studies have focused on identification of miRNA-target mRNA pairs as each miRNA can have hundreds of mRNA targets. The experimental validation of some miRNAs as oncogenic has provided further motivation for research in this area. In this article we propose an odds-ratio (OR) statistic for identification of regulatory miRNAs. It is based on integrative analysis of matched miRNA and mRNA time-course microarray data. The OR-statistic was used for (i) identification of miRNAs with regulatory potential, (ii) identification of miRNA-target mRNA pairs and (iii) identification of time lags between changes in miRNA expression and those of its target mRNAs. We applied the OR-statistic to a cancer data set and identified a small set of miRNAs that were negatively correlated to mRNAs. A literature survey revealed that some of the miRNAs that were predicted to be regulatory, were indeed oncogenic or tumor suppressors. Finally, some of the predicted miRNA targets have been shown to be experimentally valid.

INTRODUCTION

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are short non-coding RNAs, approximately 20 nucleotides long, that control gene expression by either repressing the translation of mRNA into proteins or directing the cleavage of mRNA in nematodes and higher organisms including humans. miRNAs play an important role in various biological processes e.g. the miRNAs lin-4 and let-7 have been shown to regulate the larval development in Caenorhabditis elegans (1,2). Though some human miRNAs have been shown to be oncogenic or tumor suppressors (3–7), the functions of most human miRNAs are currently unknown. Perhaps one of the reasons for this is the fact that a single miRNA targets possibly hundreds of mRNAs thereby making it hard to determine a miRNA's function without first accurately identifying its target mRNAs. The target identification process commonly involves two steps—(i) identification of miRNA–mRNA pairs using prediction models (8,9) and (ii) experimental validation of the relevant miRNA–mRNA pairs. In addition to target identification, miRNA research has focused on microarray analysis for experimental validation of oncogenic miRNAs (3–7), comparison of miRNA normalization techniques (10) and identification of coexpressed miRNAs (11).

To identify miRNAs that regulate mRNAs, one needs to co-analyze the changes in miRNA and mRNA expressions. Once the expression profiles of miRNAs and mRNAs have been obtained using microarray experiments, statistical methods are required to determine the association between the two expression profiles. Yona et al. (12) evaluated several measures of similarity between expression profiles of genes, e.g. Euclidean distance, Pearson's correlation and Spearman's rank correlation. The authors observed that the best metric varied from one data set to another though Spearman's rank correlation was consistently among the best performers. In our analysis, we used the Spearman's rank correlation as one of the measures for evaluating the association between miRNAs and mRNAs.

An important component of miRNA–mRNA data integration is the knowledge of potential mRNA targets for each miRNA. There are a number of popular target prediction algorithms such as PicTar (9), miRanda (13) [implemented in miRBase (14)] and TargetScanS (8), as well as methods that combine different prediction algorithms, e.g. miRGen (15). Each of these prediction algorithms has its strengths and weaknesses. For example, TargetScanS focuses on identification of target mRNAs by searching for 5′-dominant mRNA sites. Therefore, it is likely to miss targets that contain 3′-compensatory sites. Other algorithms such as miRanda considers both 5′-dominant and 3′-compensatory sites for target identification. While TargetScanS and miRanda focus on identification of targets for each miRNA separately, PicTar considers the combinatorial effect of coexpressed miRNAs for target prediction.

A recent paper (13) showed that TargetScanS, miRanda and PicTar have almost identical sensitivity values, where sensitivity was calculated as ‘true positives/(true positives + false negatives)’. Here, true positives corresponded to the number of experimentally validated miRNA-target mRNA pairs that were predicted by an algorithm and false negatives corresponded to the number of experimentally validated miRNA-target mRNA pairs that were not predicted by the algorithm. However, miRanda predicted nearly double the number of miRNA-target mRNA pairs predicted by the other two algorithms. The number of predicted miRNA-target mRNA pairs could be reduced by considering the intersection of two or more algorithms at the cost of lower sensitivity values. Currently only the intersection of TargetScanS and PicTar has a sensitivity value close to those returned for the individual algorithms (13).

While these predictive algorithms provided a good starting point, they returned a few hundred mRNAs as potential targets. In order to have better biological interpretation, developing statistics to identify miRNA–mRNA pairs that are most likely to be of biological significance is an important goal. To this end, we developed an odds-ratio (OR) statistic for measuring the association between putative miRNA-target mRNA pairs and identifying regulatory miRNAs.

Recently, Huang et al. (16) used a Bayesian model to determine the posterior probability of an mRNA being targeted by a miRNA. Unlike our approach that focuses on the identification of regulatory miRNAs, they focused on filtering the predicted miRNA-target mRNA pairs using an Expectation-Maximization approach. Cheng and Li (17) used the changes in expression profiles of mRNAs and knowledge of predicted miRNA-target mRNA pairs to infer whether a miRNA is regulatory. Our approach is based on the matched analysis of miRNA and mRNA expression data and considers a miRNA to be regulatory if and only if the change in expression profile of a miRNA and its predicted target-mRNAs is correlated.

Time-course studies provide information that could often be missed in a cross-sectional study based on a single time point. Currently, typical microarray time-course data is short with uneven time points and very few replicates [for a detailed review, refer (18)]. Therefore, standard time series analysis methods like Fourier transform are usually not applicable. In this article, we have used moderated t2-statistic (19) and moderated F-statistic (20); methods that have been developed for handling short time-course microarray data.

In this article we propose an integrative analysis of miRNA and mRNA data that incorporates time information to identify (i) miRNAs that are likely to regulate gene expression and (ii) their target mRNAs. We first describe the OR-statistic and later demonstrate the potential value of OR-statistic using a data set obtained from a cancer study.

METHODS

To identify regulatory miRNAs in matched microRNA-mRNA time-course data, we performed a number of distinct steps—(i) data pre-processing, (ii) identification of differentially expressed (DE) miRNAs, (iii) identification of regulatory miRNAs and (iv) identification of mRNAs that were negatively correlated to the relevant miRNAs. Application of an integrative approach to the last two steps is the main focus of this article. We applied the OR-statistic as well as the gene set test (GST)-based methods to a longitudinal time-course cancer dataset to illustrate this approach.

Experimental data

The cancer dataset corresponded to a drug study involving a multiple myeloma cell line U266, consisting of six time points—0, 2 h, 4 h, 8 h, 24 h and 48 h with two biological replicates per time point for both miRNA and mRNA. The same RNA sample for each time-course was hybridized to both the miRNA and mRNA microarrays. The miRNA expression profiles were determined using two-color Exiqon arrays V8.1 and the mRNA expression profiles were determined using Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Affymetrix arrays. Raw expression data from Exiqon array was extracted using the image analysis package Spot (21).

Statistical analysis

Data Pre-processing

miRNA arrays: These two-color arrays were pre-processed using the Bioconductor package limma (22). The background intensities were subtracted (23) followed by a within-array-normalization (24) using the global loess method.

mRNA arrays: These single-color arrays were pre-processed using the Bioconductor package affy (25) with RMA background correction (26) followed by quantile normalization (27) and summarization of gene expressions using the median polish algorithm.

Differentially expressed miRNA (mRNA)

We fit a linear model and tested the null hypothesis that there was no change in expression at any time point x with respect to time point 0, where x = 2, 4, 8, 24, and 48 h. The P-values for the F-test were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the BH correction method (28) and miRNAs with adjusted P-values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant and differentially expressed.

Discretized expression profiles

We obtained t-statistic for the null hypothesis H0: μtg = μ0g versus the alternate hypothesis H1: μtg ≠ μ0g, where μtg is the average expression of mRNA g at time point t and μ0g is the average expression at time point 0. Let Mg = [m1, …, mk]T denote the classification of t-statistic as up-regulated, down-regulated or non-differentially expressed for the g-th mRNA, where k is the number of time points excluding time point 0. In other words, mi takes the values +1, –1 or 0 based on whether the g-th mRNA is up-regulated, down-regulated or non-differentially expressed, respectively, at time point t with respect to time point 0. We will henceforth refer to Mg as the discretized expression profile for the g-th mRNA. Similar discretized expression profiles were obtained from miRNA expression data. It should be noted that the t-statistics were discretized using the limma function decideTests.

Integrative analysis

We propose a few approaches for measuring the strength of association between a miRNA and its predicted target mRNAs.

OR-statistic

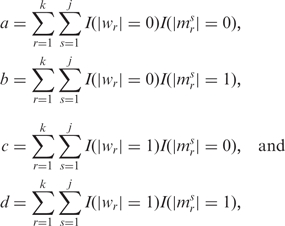

Let W and M denote the discretized expression profiles for miRNA and mRNA, respectively. Let M1, …, Mj denote the discretized expression profiles of the j mRNAs that are predicted as targets of a miRNA. As a first step, we focused on whether there was a change in expression rather than the direction of change. Let

|

where |wr| denotes the absolute value of the r-th element of miRNA vector W, |msr| denotes the r-th element for the s-th target mRNA, and I(x = y) is an indicator function that takes the value 1 if the condition is satisfied and 0, otherwise. The variables a, b, c and d were used to populate a 2 × 2 contingency table (Table 1) and obtain the OR.

Table 1.

An example 2 × 2 contingency table for determining the association between miRNA and mRNA expression change

| Target mRNA |

||

|---|---|---|

| No change | Change | |

| miRNA | ||

| No change | a | b |

| Change | c | d |

Let Odds1 = b/a and Odds2 = d/c. Then, OR = Odds2/Odds1. In other words,

where GmRNA denotes the set of j mRNAs that were predicted as a miRNA's targets.

The null hypothesis H0: OR = 1, i.e. a change in the expression of predicted target mRNAs is independent of a change in the miRNA's expression is tested using a chi-squared test with one degree of freedom. Alternatively, H0 can be tested using a G-test (29) if |Oi – Ei| > Ei for the i-th cell in the 2 × 2 contingency table. Here, Oi denotes the observed value for the i-th cell, Ei denotes the expected value for the i-th cell, and 1 ≤ i ≤ 4.

Since different miRNA-target prediction algorithms return different results for the same miRNA, the OR-statistic is dependent on the prediction algorithm. Therefore, a ranking of miRNAs based on the OR-statistic would vary from one algorithm to another. This problem is similar to many statistical problems in clinical studies that require meta-analysis techniques. In the absence of the ability to determine the optimal prediction algorithm, one solution is to combine the results from several miRNA-target prediction algorithms and determine the overall rank of a miRNA. To this end, we propose the use of Fisher's combined test (30) with the test statistic  , where pi denotes the p-value obtained using the OR-statistic for the i-th algorithm and n denotes the number of algorithms. Here, the χ2-statistic has a chi-squared distribution with 2 × n degrees of freedom. It should be noted that pi values are not independent as the results are obtained for the same data set using miRNA-target prediction algorithms with partial overlap. Therefore, the p-value for the chi-squared test should be treated with caution. In this article, we calculated the χ2-statistic for only those miRNAs that were predicted as regulatory using each of the n miRNA-target prediction algorithms. Although all the ranked miRNAs had regulatory potential, miRNAs that were ranked high by two or more algorithms were ranked high overall and were more likely to be regulatory.

, where pi denotes the p-value obtained using the OR-statistic for the i-th algorithm and n denotes the number of algorithms. Here, the χ2-statistic has a chi-squared distribution with 2 × n degrees of freedom. It should be noted that pi values are not independent as the results are obtained for the same data set using miRNA-target prediction algorithms with partial overlap. Therefore, the p-value for the chi-squared test should be treated with caution. In this article, we calculated the χ2-statistic for only those miRNAs that were predicted as regulatory using each of the n miRNA-target prediction algorithms. Although all the ranked miRNAs had regulatory potential, miRNAs that were ranked high by two or more algorithms were ranked high overall and were more likely to be regulatory.

OR-statistic with time lag

Since a change in miRNA expression may not necessarily produce an instantaneous change in target mRNA's expression, we expanded our previously discussed model to incorporate a delayed change in target mRNA's expression. We considered five different time lags (Table 2) and, for each time lag, performed the following steps:

calculated OR for each miRNA;

tested the null hypothesis that OR = 1 using a chi-squared test; and

obtained miRNAs that had OR > 1 and p-values lower than 0.05 for the chi-squared test.

Table 2.

Different time lags for changes in miRNA and mRNA expressions

| miRNA time points |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 h | 4 h | 8 h | 24 h | 48 h | ||

| mRNA time points | 2 h | 0 | ||||

| 4 h | 1 | 0 | ||||

| 8 h | 2 | 1 | 0 | |||

| 24 h | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | ||

| 48 h | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | |

The numbers correspond to the matched miRNA–mRNA time points for various time lags—(i) 0, time-lag 0; (ii) 1, time-lag 1; (iii) 2, time-lag 2; (iv) 3, time-lag 3; and (iv) 4, time-lag 4.

It should be noted that for each time lag, the vectors W and M corresponded to matched time points. For example, for time-lag 1, W = [w2, w4, w8, w24]T and M = [m4, m8, m24, m48]T, where wi and mi denote the ternary value at time point i h.

Negatively correlated miRNA–mRNA pairs

While it is important to identify regulatory miRNAs, for experimental validation of a miRNA's regulatory effect, it is equally important to determine mRNAs that are negatively correlated to it. Therefore, we identified target mRNAs whose expression levels changed in the opposite direction to that of miRNA.

Let  I(wrmr = −1) and f = m – a. Here, we dropped the superscript s from mr as we considered miRNA–mRNA pairs one at a time. The variables e and f were used to populate Table 3 and obtain the odds of a change in the discretized miRNA's expression profile resulting in a change in the opposite direction in its target mRNA. If the odds-value was greater than one, then the miRNA–mRNA pair could be considered to be negatively correlated.

I(wrmr = −1) and f = m – a. Here, we dropped the superscript s from mr as we considered miRNA–mRNA pairs one at a time. The variables e and f were used to populate Table 3 and obtain the odds of a change in the discretized miRNA's expression profile resulting in a change in the opposite direction in its target mRNA. If the odds-value was greater than one, then the miRNA–mRNA pair could be considered to be negatively correlated.

Table 3.

An example table for calculating the odds of a miRNA being negatively correlated to its target mRNA

| Change in mRNA expression in opposite direction | No change in mRNA expression or change in the same direction as miRNA | |

|---|---|---|

| Change in miRNA expression | e | f |

Gene set test-based methods

In addition to the OR-statistic, we used two GST-based methods for identifying regulatory miRNAs. In principle, the GST-based methods are similar to the gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) (31) that is used to determine whether a group of genes, selected on the basis of a priori biological knowledge, e.g. genes in a biological pathway or belonging to the same gene ontology, has an expression profile different from that for the remaining genes. Here, we determined whether a group of mRNAs, predicted as targets of a particular miRNA, has a change in expression for a change in the relevant miRNA's expression. The two GST-based methods are described below:

Correlation-coefficient-based GST method (CC-GST): We obtained t-statistic for the null hypothesis H0: μtg = μ0g versus the alternate hypothesis H1: μtg ≠ μ0g, where μtg is the average expression of miRNA (mRNA) g at time point t and μ0g is the average expression at time point 0. Next, for a given miRNA, miv, we obtained the Spearman's correlation coefficient for all miv-mRNA pairs using the t-statistic. Let X denote the set of correlation coefficients for those mRNAs that were predicted as targets of miv and let Y denote the set of remaining correlation coefficients. Since changes in miRNA expression are negatively correlated to changes in mRNA expression, we tested the null hypothesis H0: μX = μY versus the alternate hypothesis H1: μX < μY, where μX denotes the average correlation coefficient for set X and μY denotes the average correlation coefficient for set Y. We used the Wilcoxon rank-sum test (32) for testing the null hypothesis and if the P-value (after adjusting for multiple comparisons) was lower than a pre-determined cut-off value, e.g. 0.05, then we considered miv to be statistically significant.

F-statistic-based GST method (F-GST): For each mRNA, we obtained the F-statistic for the null hypothesis that there was no change in expression with respect to time point 0. Next, for a given miRNA, miv, we tested the null hypothesis H0: μX = μY versus the alternate hypothesis H1: μX ≠ μY, where μX denotes the average of F-statistics for mRNAs that were predicted as targets of miv and μY denotes the average of F-statistics for the remaining mRNAs. We used the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for hypothesis testing and if the P-value (after adjusting for multiple comparisons) was lower than a pre-determined cut-off value, e.g. 0.05, then we considered miv to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Data pre-processing

We used standard pre-processing methods for single-color (mRNA) and two-color (miRNA) arrays. However, unlike the usual print-tip loess normalization method (33) for two-color gene expression data, we used global loess normalization. As evident in Table 4, there were too few highly expressed miRNAs to allow for estimation of print-tip based loess lines at highly expressed ‘spots’. The small number of highly expressed miRNAs could be due to the fact that multiple-species miRNAs were placed on the same array and most of ‘spots’ would not have hybridized with miRNAs extracted from cancer patients.

Table 4.

Frequency table of average log2-expression from a typical miRNA expression data

| Frequency bins (log2-expression) | 5.5 | 6.5 | 7.5 | 8.5 | 9.5 | 10.5 | 11.5 | 12.5 | 13.5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Counts | 1 | 299 | 1543 | 377 | 156 | 121 | 30 | 24 | 4 |

Differentially expressed (DE) miRNAs

Using a linear model for the experimental data set, we obtained 726 DE miRNAs, out of which 193 miRNAs corresponded to a known or predicted human miRNA giving a total of 135 unique human miRNAs as DE. As mentioned earlier in the ‘Methods’ section, the DE miRNAs were obtained by testing the null hypothesis that there was no change in miRNA expression at any time point x with respect to time point 0, where x = 2, 4, 8, 24 and 48 h. We denote the set of these 135 miRNAs as U and it would be used later for identifying the regulatory miRNAs.

While miRNAs with adjusted p-values lower than a pre-determined cut-off value may be regulatory, a better method of determining regulatory miRNAs would take into account changes in expressions of both miRNA and mRNA. This is because a miRNA that is regulatory should be (i) differentially expressed over the time course and (ii) associated with changes in its target mRNAs expressions.

We found that the discretized expression profiles were usually vectors of all 0s (Table 5) which was in agreement with the widely known observation that at any given time point, the majority of miRNAs/mRNAs are not DE. It should be noted that the discretized expression profiles were obtained by testing pairwise hypotheses (refer ‘Methods’ section) which is different from the hypothesis used for determining U. Therefore, the two results were slightly different.

Table 5.

miRNAs and mRNAs that were DE at least one time point

| Is miRNA/mRNA DE? |

||

|---|---|---|

| DE | Non-DE | |

| Number of human miRNA probes | 126 | 814 |

| Number of Affymetrix probesets (mRNA) | 18274 | 36401 |

For the cancer study, we considered five different time lags (Table 2) and determined the corresponding 2 × 2 contingency table (see ‘Methods’ section). Since the majority of miRNAs/mRNAs had no change in expression, many of the OR contingency tables (i.e. Table 1) had one or more elements as 0. If even one of the elements was 0, the OR was not calculated and the results in Table 6 are based on only those miRNA for which every element in the OR matrix was strictly greater than 0.

Table 6.

Number of statistically significant miRNAs for time-lag 0 using the OR-statistic

| Is miRNA statistically significant? |

||

|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |

| PicTar | 26 | 20 |

| miRBase | 52 | 54 |

| TargetScanS | 26 | 28 |

| miRGen | 24 | 19 |

Estimating regulatory miRNAs

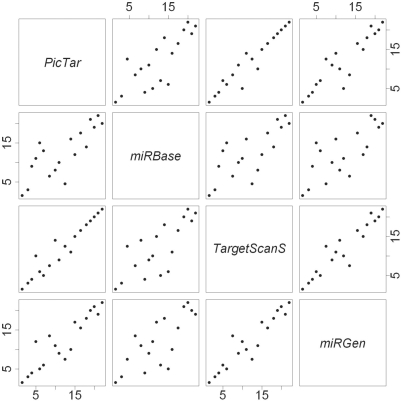

We obtained p-values for the null hypothesis H0: OR = 1 for (i) different miRNA-target prediction algorithms and (ii) different time lags. We considered four different miRNA-target prediction algorithms—(i) PicTar, (ii) TargetScanS, (iii) miRBase and (iv) miRGen (intersection of target mRNAs returned by PicTar (4-way) and TargetScanS). Figure 1 shows the concordance between the miRNA rankings for time-lag 0 using the four different algorithms. The rankings were obtained using the p-values for the OR-statistic such that the miRNA with the lowest p-value was ranked 1. While the rankings obtained using PicTar and TargetScanS were quite similar, they differed from that obtained using miRBase. Since the rankings were not consistent, we used the Fisher's combined test to obtain the overall rank of miRNAs. The G-test and the chi-squared test selected the same miRNAs as regulatory for every combination of miRNA-target prediction algorithm and time-lag. Also, the overall ranks obtained using G-test and chi-squared test were similar with only some of the miRNAs being ranked slightly different. We decided to use only the chi-squared test's results for the rest of the analysis.

Figure 1.

Pair-wise concordance between miRNA rankings obtained for time-lag 0 using PicTar, TargetScanS, miRBase and miRGen. The plot is represented as a 4 × 4 grid with the upper-diagonal cells and the lower diagonal cells being mirror images. For example, while the graph in cell (1, 2) has PicTar rankings on the Y-axis and miRBase rankings on the X-axis, the graph in cell (2, 1) has PicTar rankings on the X-axis and miRBase rankings on the Y-axis.

For a particular time lag, we considered a miRNA to be regulatory if (i) the p-value for the chi-squared test (based on the OR-statistic) was statistically significant, (ii) the OR value was greater than 1, and (iii) the miRNA was DE (i.e. miRNA was found in set U). We obtained 20 miRNAs of interest and some of these were identified as regulatory for more than one time lag, e.g. hsa-miR-16 was found to be regulatory for time-lag 0 and time-lag 1. We obtained 33 miRNA-time lag combinations of interest and hsa-miR-16 was ranked the highest with a time lag of 0. Other top-ranked miRNAs included hsa-miR-30b (time-lag 1), hsa-miR-20a (time-lag 1), hsa-miR-148a (time-lag 2) and hsa-miR-181c (time-lag 2).

It should be noted that since the dataset was longitudinal, considering the miRNA/mRNA expressions at different time points as independent and using the moderated t-statistic to discretize the expression profiles may have resulted in some false positives and false negatives e.g. (34).

Negative correlation between miRNA and mRNA

For each regulatory miRNA, we determined mRNAs that were negatively correlated using matched miRNA–mRNA discretized expression profiles. For example, while considering miRNA–mRNA correlation for time-lag 1 (Table 2), a change in miRNA expression at time point t = 2 h was matched to a change in mRNA expression at time point t = 4 h.

Since a single mRNA maps to i probesets on the Affymetrix chip (i ≥ 1), we obtained the values ei and fi for each miRNA-probeset combination, where ei and fi denote the elements e and f in Table 3 for miRNA-probeseti combination. Next we calculated the odds of negative correlation i.e. the ratio  . For each miRNA-target prediction algorithm, we found a few miRNA–mRNA pairs with odds greater than one and therefore, negatively correlated.

. For each miRNA-target prediction algorithm, we found a few miRNA–mRNA pairs with odds greater than one and therefore, negatively correlated.

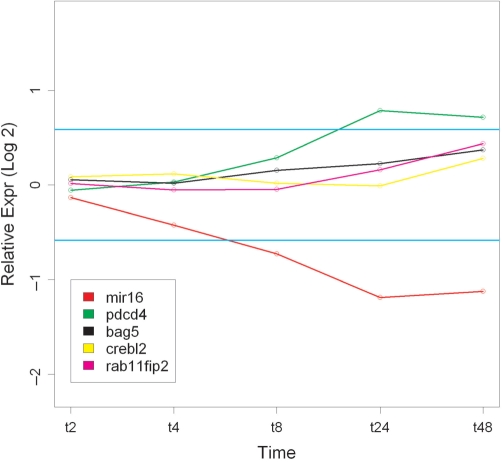

Figure 2 shows the log2-fold change over the time course for hsa-miR-16 and some of the negatively correlated target mRNAs. These target mRNAs were selected as PDCD4, CREBL2 and RAB11FIP2 have been experimentally validated as hsa-miR-16's targets (3). BAG5 was selected as Bcl2 is a known hsa-miR-16 target (3), but it was identified using proteomics and not mRNA microarray data. Perhaps hsa-miR-16 regulates Bcl2 expression via BAG5.

Figure 2.

Log2-fold change values for hsa-miR-16 and some of its targets mRNAs identified using OR-statistic. The horizontal blue lines correspond to 1.5-fold change (log2 value of 0.58).

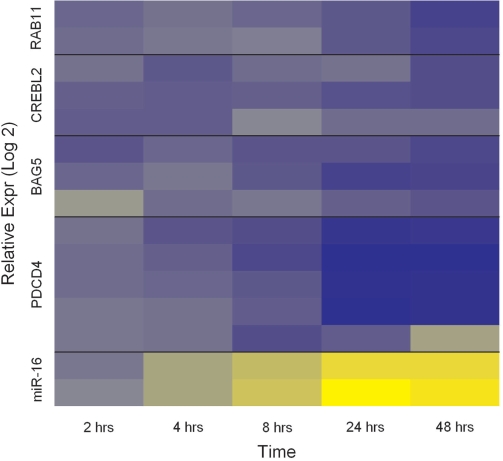

Since each target mRNA maps to multiple probe-sets, the values in Figure 2 represent the median values per time point. For each target mRNA, we observed some variability in fold change values among the probesets and this is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Log2-fold change values per miRNA probe/mRNA probeset. hsa-miR-16 had probes in duplicate and the target mRNAs map to multiple probesets, the number of probesets varying from one mRNA to another. Blue denotes over-expression with respect to time t = 0 and yellow denotes under-expression with respect to time t = 0. RAB11 corresponds to the gene RAB11FIP2.

Concordance with results obtained using GST-based methods

We also obtained regulatory miRNAs using the two GST-based methods as follows:

CC-GST: For time-lag 0, we obtained statistically significant miRNAs for each of the four miRNA-target prediction algorithms. We considered a miRNA to be regulatory if it was statistically significant using CC-GST and DE (i.e. miRNA was found in set U). Unlike the result obtained using OR-statistic, we did not find any miRNA that was common to all the four algorithms.

F-GST: For each miRNA target prediction algorithm, we obtained statistically significant miRNAs for each of the four miRNA-target prediction algorithms. We considered a miRNA to be regulatory if it was statistically significant using F-GST and DE (i.e. miRNA was found in set U). We found 19 miRNAs common to all the four target prediction algorithms. However, only six of these miRNAs were also obtained using the OR-statistic. In fact, hsa-miR-16, the highest ranked miRNA obtained using the OR-statistic, was not found using the F-GST method. Therefore, there was little agreement between the miRNAs returned by the two methods.

DISCUSSIONS

In this article, we propose an OR-statistic for integrating miRNA and mRNA expression profiles using time-course data and obtaining the miRNA–mRNA pairs of interest. Since miRNAs are a part of gene regulatory mechanism, they could be possible targets for drug development.

A literature search revealed that some of the miRNAs identified using the OR-statistic have been shown to be oncogenic or tumor suppressors. For example, hsa-miR-16, the highest ranked miRNA in our analysis, has been linked to chronic lymphocytic leukemia (35) and mantle cell lymphoma (36). Similarly, hsa-miR-20a has been linked to breast cancer and lung cancer (37). hsa-miR-148 has been shown to target DNA methyltransferase 3b (DNMT3b) gene (38) and a reduced expression of DNMT3b has been shown to induce apoptosis of cancer cells (39). Another miRNA, hsa-miR-21 (time-lag 0 and rank 22), has been shown to be oncogenic in multiple myeloma cells (40).

We observed that only 26.6% of the DE miRNAs mapped to known human miRNAs. Although miRNA sequences are highly conserved across species, many miRNAs that are found in species such as mouse, and are likely to have human counterparts, have currently not been validated in humans. Infact only 30.6% of the probes on Exiqon arrays were mapped to a known human miRNA. Another possible reason could be that ∼10% of the probes on Exiqon arrays correspond to computationally predicted or poorly characterized miRNAs. It is likely that some of these miRNAs are present in humans but are currently un-annotated.

The OR-statistic could be extended to incorporate some of the combinatorial effects of miRNA-based gene regulation. Instead of evaluating a miRNA's regulatory potential, one could look at miRNAs that are co-expressed and determine this group's regulatory potential as a unit. However, this would require either a priori knowledge of miRNA modules or a model-based approach to miRNA module identification. Recently Joung et al. (11) used an evolutionary algorithm to identify miRNA-modules and matched them to mRNA-modules but currently their method is not applicable to time-course data.

Due to the nature of short time-course data, the calculation of correlation between miRNA and mRNA based on actual expression values introduces too much noise. Therefore, we chose to discretize the miRNA/mRNA expression profiles into vectors of 0, +1 and –1. Though there could be a loss of information owing to this discretization, we believe that the reduction in noise outweighs this potential problem. Moreover, our approach could be easily adapted to longer time-course data and the OR-statistic could be calculated using Pearson's correlation-coefficient (based on actual expressions) or Spearman's correlation-coefficient (based on moderated t-statistic) with correlation-coefficients above a threshold being discretized to 1 and those below the threshold being discretized to 0.

The OR-statistic, CC-GST, and F-GST are different metrics for identifying regulatory miRNAs. For time-lag 0, we obtained results using not only the OR-statistic but also the GST-based methods. For time-lag 0, the CC-GST method did not return any miRNA that was common to all the four miRNA-target prediction algorithms. This raises concerns about the reliability of correlation-coefficient based methods for short time-course data because a miRNA that is identified by several algorithms is more likely to be regulatory compared to one that is identified by only one algorithm. Unlike the OR-statistic that can be used for all possible time lags (Table 2), the CC-GST can only be used for time-lag 0. For the remaining time lags, there are very few (≤4) data points making it hard to distinguish between genuine correlations and those by chance. However, for a longer time-series data set, this will not be a limitation. We also used the F-GST method to obtain regulatory miRNAs for time-lag 0. The results obtained using the F-GST method and the OR-statistic were not in agreement. The F-GST method returned 19 regulatory miRNAs and the OR-statistic-based method returned 20 regulatory miRNAs but only six miRNAs were common to the two methods. It should be noted that the F-GST method cannot be used to determine the time lag between changes in miRNA expression and mRNA expression. Since the identification of time lag is essential for any experimental validation of results, the F-GST method may be of limited use.

If we had a priori biological knowledge of the miRNAs that were regulatory (i.e. a gold standard), we could have compared the results obtained using F-GST and OR-statistic. We would have preferred the method that had more ‘true’ regulatory miRNAs in the list but currently such a gold standard is unavailable. A literature survey (7) revealed that some of the miRNAs identified using the OR-statistic have been experimentally validated in multiple myeloma patients. However, currently only one of the miRNAs returned by the F-GST method has been experimentally validated. Therefore, the experimental data favor OR-statistic as the method of choice for identifying regulatory miRNAs.

Finally, both OR-statistic and GST-based methods are dependent on the quality of miRNA-target prediction algorithms. Since currently there is no one algorithm that outperforms others in terms of sensitivity and specificity, we used the popular algorithms and obtained miRNAs of interest by combining the various algorithm-specific results. As the accuracy of miRNA-target prediction improves, the accuracy of these methods will also improve. The methods described in this article have been implemented in R (41). The GST-based analysis is a part of the mirGst package and the R scripts related to the integrative analysis are available upon request.

FUNDING

Australian Research Council grant DP0770395 (to Y.Y. and V.J.); St. Vincent's Hospital Haematology Research Fund (to D.M. and M.L.); Arrow Bone Marrow Transplant Foundation (to M.L.) and Sydney Medical Research Foundation (to D.M.); financial support from Arrow BMT Foundation and Sydney Medical Research Foundation (to M.L. and D.M.). Funding for open access charge: School of Mathematics and Statistics' Research Incentive Scheme (University of Sydney).

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr Tiffany Khong and Dr Andrew Spencer of the Myeloma Research Group, Alfred Hospital, Melbourne, Australia for providing the treated cell line samples. The authors would like to thank the two reviewers for their comments and feedback that helped in improving the paper. The authors would like to thank Dr Ru-Fang Yeh for discussions relating to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ambros V. A hierarchy of regulatory genes controls a larva-to-adult developmental switch in C. elegans. Cell. 1989;57:49–57. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90171-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruvkun G, Giusto J. The Caenorhabditis elegans heterochronic gene Lin-14 encodes a nuclear-protein that forms a temporal developmental switch. Nature. 1989;338:313–319. doi: 10.1038/338313a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calin GA, Cimmino A, Fabbri M, Ferracin M, Wojcik SE, Shimizu M, Taccioli C, Zanesi N, Garzon R, Aqeilan RI, et al. MiR-15a and miR-16-1 cluster functions in human leukemia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:5166–5171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800121105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Debernardi S, Skoulakis S, Molloy G, Chaplin T, Dixon-McIver A, Young BD. MicroRNA miR-181a correlates with morphological sub-class of acute myeloid leukaemia and the expression of its target genes in global genome-wide analysis. Leukemia. 2007;21:912–916. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.He L, Thomson JM, Hemann MT, Hernando-Monge E, Mu D, Goodson S, Powers S, Cordon-Cardo C, Lowe SW, Hannon GJ, et al. A microRNA polycistron as a potential human oncogene. Nature. 2005;435:828–833. doi: 10.1038/nature03552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu J, Getz G, Miska EA, Alvarez-Saavedra E, Lamb J, Peck D, Sweet-Cordero A, Ebet BL, Mak RH, Ferrando AA, et al. MicroRNA expression profiles classify human cancers. Nature. 2005;435:834–838. doi: 10.1038/nature03702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pichiorri F, Suh S-S, Ladetto M, Kuehl M, Palumbo T, Drandi D, Taccioli C, Zanesi N, Alder H, Hagan JP, et al. MicroRNAs regulate critical genes associated with multiple myeloma pathogenesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:12885–12890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806202105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell. 2005;120:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krek A, Grun D, Poy MN, Wolf R, Rosenberg L, Epstein EJ, MacMenamin P, da Piedade I, Gunsalus KC, Stoffel M, et al. Combinatorial microRNA target predictions. Nat. Genet. 2005;37:495–500. doi: 10.1038/ng1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rao YL, Lee Y, Jarjoura D, Ruppert AS, Liu CG, Hsu JC, Hagan JP. A comparison of normalization techniques for microRNA microarray data. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2008;7:1–18. doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joung JG, Hwang KB, Nam JW, Kim SJ, Zhang BT. Discovery of microRNA-mRNA modules via population-based probabilistic learning. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:1141–1147. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yona G, Dirks W, Rahman S, Lin DM. Effective similarity measures for expression profiles. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1616–1622. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.John B, Enright AJ, Aravin A, Tuschl T, Sander C, Marks DS. Human microRNA targets (vol 2, pg 1862, 2005) PLos Biol. 2005;3:1328. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Griffiths-Jones S, Grocock RJ, van Dongen S, Bateman A, Enright AJ. miRBase: microRNA sequences, targets and gene nomenclature. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D140–D144. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Megraw M, Sethupathy P, Corda B, Hatzigeorgiou AG. miRGen: a database for the study of animal microRNA genomic organization and function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D149–D155. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang JC, Frey BJ, Morris QD. Comparing sequence and expression for predicting microrna targets using genmir3. Pac. Symp. Biocomput. 2008;13:52–63. doi: 10.1142/9789812776136_0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng C, Li LM. Inferring microrna activities by combining gene expression with microrna target prediction. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1989. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tai YC, Speed TP. In: DNA Microarrays. Nuber U, editor. New York: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tai YC, Speed TP. A multivariate empirical Bayes statistic for replicated microarray time course data. Ann. Stat. 2006;34:2387–2412. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smyth GK. Linear models and empirical bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2004;3 doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1027. Article3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang YH, Buckley MJ, Dudoit S, Speed TP. Comparison of methods for image analysis on cDNA microarray data. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 2002;11:108–36. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smyth GK. Limma: Linear Models for Microarray Data. In: Gentleman R, Carey V, Dudoit S, Irizarry R, Huber W, editors. Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Solutions using R and Bioconductor. New York: Springer; 2005. pp. 397–420. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ritchie ME, Silver J, Oshlack A, Holmes M, Diyagama D, Holloway A, Smyth GK. A comparison of background correction methods for two-colour microarrays. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2700–2707. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smyth GK, Speed T. Normalization of cDNA microarray data. Methods. 2003;31:265–273. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(03)00155-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Irizarry RA, Gautier L, Cope LM. An R Package for Analyses of Affymetrix Oligonucleotide Arrays. In: Parmigiani G, Garrett ES, Irizarry RA, Zeger SL, editors. The Analysis of Gene Expression Data: Methods and Software. New York: Springer; 2003. pp. 102–119. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Irizarry RA, Hobbs B, Collin F, Beazer-Barclay YD, Antonellis KJ, Scherf U, Speed TP. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics. 2003;4:249–264. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/4.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bolstad BM, Irizarry RA, Astrand M, Speed TP. A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:185–193. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate – a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B-Methodol. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sokal RR, Rohlf FJ. Biometry: The Principles and Practice of Statistics in Biological Research. 3rd edn. New York: Freeman; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fisher R. Statistical Methods for Research Workers. London: Oliver and Boyd; 1932. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bauer DF. Constructing confidence sets using rank statistics. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1972;67:687–690. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang YH, Dudoit S, Luu P, Lin DM, Peng V, Ngai J, Speed TP. Normalization for cDNA microarray data: a robust composite method addressing single and multiple slide systematic variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:1–10. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.4.e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tai YC, Speed TP. On gene ranking using replicated microarray time course data. Biometrics. 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2008.01057.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2008.01057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Calin GA, Dumitru CD, Shimizu M, Bichi R, Zupo S, Noch E, Aldler H, Rattan S, Keating M, Rai K, et al. Frequent deletions and down-regulation of micro-RNA genes miR15 and miR16 at 13q14 in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:15524–15529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242606799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen RW, Bemis LT, Amato CM, Myint H, Tran H, Birks DK, Eckhardt SG, Robinson WA. Truncation in CCND1 mRNA alters miR-16-1 regulation in mantle cell lymphoma. Blood. 2008;112:822–829. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-142182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Volinia S, Calin GA, Liu CG, Ambs S, Cimmino A, Petrocca F, Visone R, Iorio M, Roldo C, Ferracin M, et al. A microRNA expression signature of human solid tumors defines cancer gene targets. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:2257–2261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510565103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Duursma AM, Kedde M, Schrier M, Le Sage C, Agami R. miR-148 targets human DNMT3b protein coding region. Rna-a Publ. Rna Soc. 2008;14:872–877. doi: 10.1261/rna.972008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beaulieu N, Morin S, Chute IC, Robert MF, Nguyen H, MacLeod AR. An essential role for DNA methyltransferase DNMT3B in cancer cell survival. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:28176–28181. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204734200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Loffler D, Brocke-Heidrich K, Pfeifer G, Stocsits C, Hackermuller J, Kretzschmar AK, Burger R, Gramatzki M, Blumert C, Bauer K, et al. Inerleukin-6-dependent survival of multiple myeloma cells involves the Stat3-mediated induction of microRNA-21 through a highly conserved enhancer. Blood. 2007;110:1330–1333. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-081133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Team RDC. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Austria: Vienna; 2007. [Google Scholar]