Abstract

Few studies have examined predictors of weight regain after significant weight losses. This prospective study examined behavioral and psychological predictors of weight regain in 261 individuals who had lost an average of 18.2 ± 7.4 % of their initial body weight and completed an 18-month randomized, controlled trial of weight regain prevention comparing a newsletter control condition with self-regulation interventions delivered either face-to-face or via the Internet. Linear mixed effect models were used to examine behavioral and psychological predictors of weight regain, both as main effects and as interactions with treatment group. These analyses showed that decreases in physical activity were related to weight regain across all three groups, and that increased frequency of self-weighing was equally protective in the two intervention groups, but not in the control. Changes in psychological parameters, including increases in depressive symptoms, disinhibition, and hunger, were also related to weight regain in all groups. Although the impact of changes in restraint was greatest in the Internet group and weakest in face-to-face, the face-to-face group was the only group with increases (rather than decreases) in restraint over time, and consequent decreases in their magnitude of weight regain. Future programs for weight loss maintenance should focus on maintaining physical activity and frequent self-weighing, and include stronger components to modify psychological parameters.

Keywords: behavioral predictors, psychological predictors, weight regain prevention, weight loss maintenance

Long-term maintenance of weight loss is a major problem in the treatment of obesity. Although initial weight losses have improved over time (Wadden, Butryn, & Byrne, 2004), participants still regain significant amounts of weight. To date, most of the research analyzing predictors of weight regain has been done in the context of behavioral weight control programs, where weight losses average 10 kg at 6 months with approximately 55% losing ≥ 5% and 29 % losing ≥ 10% of their initial body weight (Wadden et al., 2005).

Fewer studies have addressed predictors of weight regain after more significant weight losses. A recent analysis using the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) database included 1310 individuals who had lost at least 10% of their body weight (Weiss, Galuska, Khan, Gillespie, & Serdula, 2007). Weight regain of > 5% over the next year (vs. weight loss or weight maintenance) was associated with Mexican American ethnicity, losing a greater percentage of maximum weight, having fewer years since reaching maximum weight, reporting greater daily screen time, attempting to control weight, and being sedentary or not meeting the public health recommendations for physical activity. The National Weight Control Registry (NWCR) had examined weight regain in individuals (sample ranging from N = 714 to N = 3003) who reported an initial weight loss of at least 30 lb (mean = 67 lb) and kept it off for at least one year (mean = 5.7 years) (Butryn, Phelan, Hill, & Wing, 2007; McGuire, Wing, Klem, Lang, & Hill, 1999; Raynor, Phelan, Hill, & Wing, 2006). Key predictors of weight regain in this sample included the following variables: larger initial percent weight loss, shorter duration of weight loss maintenance, psychological variables (baseline levels of disinhibition and depressive symptoms, and changes in restraint, hunger and disinhibition) and behavioral variables (changes in physical activity, dietary fat intake, self-weighing, TV viewing) (Butryn et al., 2007; McGuire et al., 1999; Raynor et al., 2006). Since these prior studies are limited by the use of self-report measures of body weight, further research assessing a comprehensive set of variables that might be associated with objectively measured weight regain in those who have lost a substantial amount of weight is clearly needed.

STOP Regain was an 18-month controlled trial involving individuals who had lost at least 10% of their body weight (mean = 20%) within the past 2 years (Wing, Tate, Gorin, Raynor, & Fava, 2006). These participants were randomly assigned to either a control group or to a self-regulation intervention delivered face-to-face or via the Internet. We have reported that the face-to-face intervention was effective in reducing the magnitude of weight regain and that both the face-to-face and Internet program reduced the proportion of individuals who regained > 5 lb over the 18 months (Wing et al., 2006). In the present paper, we examined the association between baseline, 6, 12 and 18 month behavioral and psychological factors and magnitude of weight regain and sought to determine whether the variables associated with success differed by treatment group.

METHOD

Subjects

Participants in STOP Regain were required to have lost ≥ 10% of their body weight within the past 2 years using any non-surgical approach. Subjects were recruited through newspaper advertisements, brochures, and contact with commercial and research weight-control programs in the Rhode Island area. The magnitude and timing of weight loss was verified in writing by a physician, friend, or weight loss counselor. Exclusion criteria included serious medical or psychological disorders, pregnancy, or a planned move. A total of 314 participants entered the trial. Although 18-month weight data was obtained on 291 of these participants, full questionnaires were available on 261 (83%) who form the sample for the present analysis. These 261 study completers were predominantly female (82%) and Caucasian (98%), with an average age of 51.2 ± 10.2 years. They had lost an average of 18.2 ± 7.4% (17.9 ± 10.4 kg) of body weight from their lifetime maximum weight, and had a current body mass index (BMI) of 28.5 ± 4.8 kg/m2. They did not differ from the remaining 53 subjects on any of the baseline variables, including BMI (28.5 ± 4.8 vs 29.5 ± 4.4 kg/m2; p = .16), with one exception: noncompleters were heavier at baseline (81.9 ± 16.9 vs. 76.8 ± 15.8 kg; p = .04).

Study Design

Participants were stratified according to the amount of weight loss they achieved prior to the study (10 – 20% vs. > 20% of body weight) and were then randomized to a control group that received quarterly newsletters or to an Internet or face-to-face intervention group. Participants were assessed at baseline, 6, 12, and 18 months and paid $25 for attending the 6 and 12-month sessions and $50 at 18 months. The protocol was approved by the Miriam Hospital Institutional Review Board.

Intervention

The face-to-face and Internet intervention included identical content, differing only in the mode of presentation (Wing et al., 2006). The interventions were based on self-regulation theory (Kanfer & Goldstein, 1975) and included 4 initial weekly meetings followed by monthly meetings for the remainder of the 18 months. Both groups were taught to weigh themselves daily and to use the information from the scale to determine if changes in eating and exercise behaviors were needed. Participants submitted their weight weekly (via phone or web-based form) and were provided with monthly token reinforcers if they were within 1.4 kg of starting weight. If weight gains of 1.4 – 2.2 kg were experienced, participants were taught to problem solve, and for weight gains ≥ 2.3 kg to restart weight loss efforts. Those who gained ≥ 2.3 kg were also offered additional counseling (via email for Internet group and in person or by phone for face-to-face group). Lessons were presented by the same staff across the two conditions either in face-to-face classes or Internet chat rooms. The lessons focused on issues related to maintenance of weight loss and recommended strategies that had been used successfully by NWCR members to maintain their weight loss, including exercising 60 minutes per day.

Assessments

Assessments were completed by blinded staff and included the following:

Weight/height

Weight was assessed using a calibrated scale with the participants dressed in light street clothes. Height was measured at baseline using a stadiometer and was used to compute body mass index (BMI).

Paffenbarger Questionnaire

The Paffenbarger questionnaire (Paffenbarger, Wing, & Hyde, 1978) was completed to indicate the number of stairs climbed, blocks walked, and sports activity during the previous week. This questionnaire is scored to determine total energy expenditure (kcal/week expended) and has been shown to relate to weight loss maintenance in a variety of prior studies (Jeffery & French, 1999; Jeffery, Wing, Sherwood, & Tate, 2003; McGuire et al., 1999).

Block Food Frequency Questionnaire

The Block Food Frequency Questionnaire asks about portion size and frequency of consumption of commonly consumed food items and is scored to indicate total calories and percent of calories from fat, protein and carbohydrates (Block et al., 1986).

Eating Inventory

Restraint (degree of conscious control over eating), disinhibition (susceptibility to loss of control over eating), and hunger (susceptibility to eat in response to hunger) were assessed using the Eating Inventory (Stunkard & Messick, 1985).

Depressive Symptomology

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) was used to assess depressive symptomology (Beck & Steer, 1987).

Frequency of Weighing

Subjects were asked to indicate on a 7-point scale how frequently they had weighed themselves during the past several months ranging from several times a day to never and recoded with higher numbers representing more frequent self-weighing. (1 = never; 2 = less than once per month; 3 = less than once per week; 4 = one time per week; 5 = several times per week; 6 = one time each day; 7 = several times per day).

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using Linear Mixed Effects (LME) models, as implemented in Splus 8.2 (Insightful Corporation, 2007). Longitudinal weight change trajectories in particular were estimated by jointly analyzing all three follow-ups (6-month, 12-month, and 18-month data) using a random intercept model to accommodate within-subject correlation across time. Weight change at follow-up was regressed upon its own baseline, time, treatment arm, demographic information, and baseline values of behavioral and psychological variables. Baseline demographic variables were retained in the model irrespective of the statistical significance of the respective regression coefficients, in order to allow estimation of longitudinal trajectories tailored to these particular participant characteristics. Possible interactions of time with time-invariant covariates (e.g., treatment group, demographics, baseline values of behavioral and psychological variables) were examined using forward selection. Subsequently, main effects of time-varying covariates (e.g., change in behavioral and psychological variables) and their interactions with treatment arm were added to the model, in order to determine which variables were related to successful weight loss maintenance.

All continuous variables were standardized by subtracting off their baseline mean and dividing by their baseline standard deviation, using values listed in Table 1. Therefore, effect sizes in the original measurement scale can be obtained by multiplying the standardized regression coefficients reported in Tables 2 and 3 by the baseline standard deviations listed in Table 1. Study group (N=Newsletter, F=Face-to-Face, I=Internet) was coded with the control arm N as the reference group, and contrasts given by (F-I)/2, i.e. the difference between the active treatment arms, and (F+I)/2-N, i.e. the difference of the average of the two active treatment arms from the control arm. Time was coded as 0, 1, 2 respectively at the 6-month, 12-month, and 18-month follow-ups, and gender was coded as a binary indicator (Female=0, Male=1). In this parameterization, the intercept represents weight regain among typical female newsletter recipients during the first 6 months of follow-up, while terms involving time represent either the rate of weight regain from 6 to 18 months (time slope) or time-varying effects of baseline covariates upon weight regain rates (time by covariate interactions). Similarly, terms involving treatment effects represent between-arm differences in either the overall intercept (group main effects) or in the slope of time-varying covariates (group by covariate interactions). Once the statistical significance of particular between-group differences was established, these differences were further evaluated by constructing group-specific estimates of the respective regression coefficients. Given our choice of treatment contrasts, these were constructed from the model output depicted in Table 2, using the relations F=N+[(F+I)/2-N]+(F-I)/2, and I=N+[(F+I)/2-N]-(F-I)/2. Results are shown in Table 3.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics at Baseline (N=261).

| Variable | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 51.16 | 10.19 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.46 | 4.83 |

| Months duration of >10% Weight Change | 13.25 | 7.61 |

| % Below Maximum Weight | 18.17 | 7.36 |

| Total Exercise Expenditure (kcal/week) | 2042 | 1450 |

| Caloric Intake (kcal/day) | 1638 | 638 |

| % Calories from Fat | 34.47 | 8.74 |

| Weighing Frequency a | 5.06 | 1.29 |

| Beck Depression Inventory | 3.91 | 3.88 |

| Eating Inventory – Hunger | 5.33 | 3.39 |

| Eating Inventory – Disinhibition | 8.31 | 3.49 |

| Eating Inventory – Restraint | 15.01 | 3.32 |

| Weight (kg) | 76.84 | 15.82 |

NOTE: BMI = Body Mass Index; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory (Beck & Steer, 1987); EI = Eating Inventory (Stunkard & Messick, 1985).

1 = never; 2 = less than once per month; 3 = less than once per week; 4 = one time per week; 5 = several times per week; 6 = one time each day; 7 = several times per day.

Table 2.

Longitudinal regression model predicting weight change since baseline at the 6-month, 12-month, and 18-month follow-up.

| Variable | Value | SE | DF | t | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline to 6 months | |||||

| Intercept | .0649 | .0321 | 472 | 2.0254 | .0434 |

| Group (Face-to-Face vs Internet) | -.0416 | .0238 | 253 | -1.7470 | .0818 |

| Group (Active Interventions vs. Control) | .0039 | .0238 | 253 | .1006 | .9200 |

| Baseline Weight | .0054 | .0201 | 253 | 0.2685 | .7885 |

| % Below Maximum Weight | .0166 | .0186 | 253 | .8916 | .3735 |

| Time since onset of >10% weight change (months) | -.0117 | .0167 | 253 | -.7009 | .4840 |

| Male | .0067 | .0482 | 253 | .1382 | .8902 |

| Age | .0113 | .0165 | 253 | .6852 | .4939 |

| 6 to 18 months | |||||

| Time | .0985 | .0129 | 472 | 7.6615 | <.0001 |

| Time * Group (Face-to-Face vs Internet) | -.0051 | .0096 | 472 | -.5387 | .5903 |

| Time * Group (Active Interventions vs. Control) | -.0339 | .0160 | 472 | -2.1163 | .0348 |

| Time * Baseline Weight | .0270 | .0076 | 472 | 3.5609 | .0004 |

| Time * % Below Maximum Weight | .0459 | .0076 | 472 | 6.0715 | <.0001 |

| Change in Behavior and Psychological Variables | |||||

| Change in Total Energy Expenditure | -.0353 | .0101 | 472 | -3.5154 | .0005 |

| Change in Caloric Intake | .0105 | .0129 | 472 | .8182 | .4136 |

| Change in % Calories from Fat | .0014 | .0124 | 472 | .1111 | .9115 |

| Change in Weighing Frequency | -.0099 | .0180 | 472 | -.5486 | .5835 |

| Change in Weighing Frequency * Group (Face-to-Face vs Internet) | .0186 | .0142 | 472 | 1.3103 | .1907 |

| Change in Weighing Frequency * Group (Active Interventions vs. Control) | -.0800 | .0229 | 472 | -3.5006 | .0005 |

| Change in BDI | .0600 | .0088 | 472 | 6.8411 | <.0001 |

| Change in Hunger | .0412 | .0136 | 472 | 3.0164 | .0027 |

| Change in Disinhibition | .0679 | .0153 | 472 | 4.4320 | <.0001 |

| Change in Restraint | -.0558 | .0170 | 472 | -3.2883 | .0011 |

| Change in Restraint * Group (Face-to-Face vs Internet) | .0479 | .0127 | 472 | 3.7642 | .0002 |

| Change in Restraint * Group (Active Interventions vs. Control) | -.0212 | .0210 | 472 | -1.0111 | .3125 |

NOTE: Time has been coded as 0, 1, 2 respectively at the 6-month, 12-month, and 18-month follow-up. All other continuous variables have been standardized by subtracting off their baseline mean and dividing by their baseline standard deviation, using values listed in Table 1. Study group has been coded with the control arm (N=Newsletter) as the reference group. Treatment contrasts are given by a) the difference between the two active treatment arms (F=Face-to-Face, I=Internet), and b) the difference of their average of the two active treatment arms from the control arm.

Table 3.

Point estimates and 95% confidence intervals of standardized group-specific intercepts and slopes in longitudinal regression model predicting weight change since baseline at the 6-month, 12-month, and 18-month follow-up.

| Variable | Group | Value | Lower Confidence Interval | Upper Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | Newsletter | .0649 | .0019 | .1279 |

| Internet | .1104 | .0406 | .1803 | |

| Face-to-Face | .0273 | -.0402 | .0948 | |

| Slope: Time | Newsletter | .0985 | .0733 | .1238 |

| Internet | .0698 | .0427 | .0969 | |

| Face-to-Face | .0595 | .0334 | .0856 | |

| Slope: Change in Weighing Frequency | Newsletter | -.0099 | -.0452 | .0255 |

| Internet | -.1085 | -.1438 | -.0732 | |

| Face-to-Face | -.0713 | -.1146 | -.0280 | |

| Slope: Change in Restraint | Newsletter | -.0558 | -.0891 | -.0224 |

| Internet | -.1249 | -.1577 | -.0921 | |

| Face-to-Face | -.0291 | -.0688 | .0106 |

NOTE: Time has been coded as 0, 1, 2 respectively at the 6-month, 12-month, and 18-month follow-up. All other continuous variables have been standardized by subtracting off their baseline mean and dividing by their baseline standard deviation, using values listed in Table 1. Study group has been coded with the control arm (N=Newsletter) as the reference group. Treatment contrasts are given by a) the difference between the two active treatment arms (F=Face-to-Face, I=Internet), and b) the difference of their average of the two active treatment arms from the control arm.

RESULTS

Baseline Variables as Predictors

None of the baseline values of the behavioral or psychological variables of interest were predictive of outcome at any follow-up point and, thus, they were dropped from the model. Moreover, the demographic (age, gender) and weight-related variables at baseline (baseline weight, percent weight loss from maximum, and time since onset of >10% weight change) were not related to rates of weight regain from 0 to 6 months. However, weight regain from 6 to 18 months was greater in those who were heavier at baseline (p=.0004) and those who had lost more weight before entering the program (p<.0001).

Changes in Behavioral Variables

Changes in physical activity were strongly associated with weight change (p=.0005). The Internet and newsletter groups reported decreases in activity over time, while exercise remained more consistent in the face-to-face group. Results from Tables 2 and 3 show that a decrease of 500 kcal/week in total energy expenditure was associated with greater weight regain of .19 kg (95% CI = .084, .301). In contrast, changes in the number of calories consumed (p=.41) or in the percent of calories from fat (p=.91) were not related to weight regain.

The other behavioral variable associated with weight regain was change in self-weighing frequency, whose effect showed significant between-group variation (F(2,472)=7.089, p=.0009). Based upon the parameterization employed in Table 2, changes in self-weighing frequency were unrelated to weight regain in the control arm (p=.58), but were strongly associated with weight changes within the two intervention arms (p=.0005), with a non-significant difference between them (p=.19). For the combined interventions, a one unit increase in self-weighing frequency (e.g. from several times a week to once daily) was associated with .98 kg (95% CI = .431, 1.532) less weight regain among intervention subjects relative to control subjects who reported the same changes on this behavioral measure.

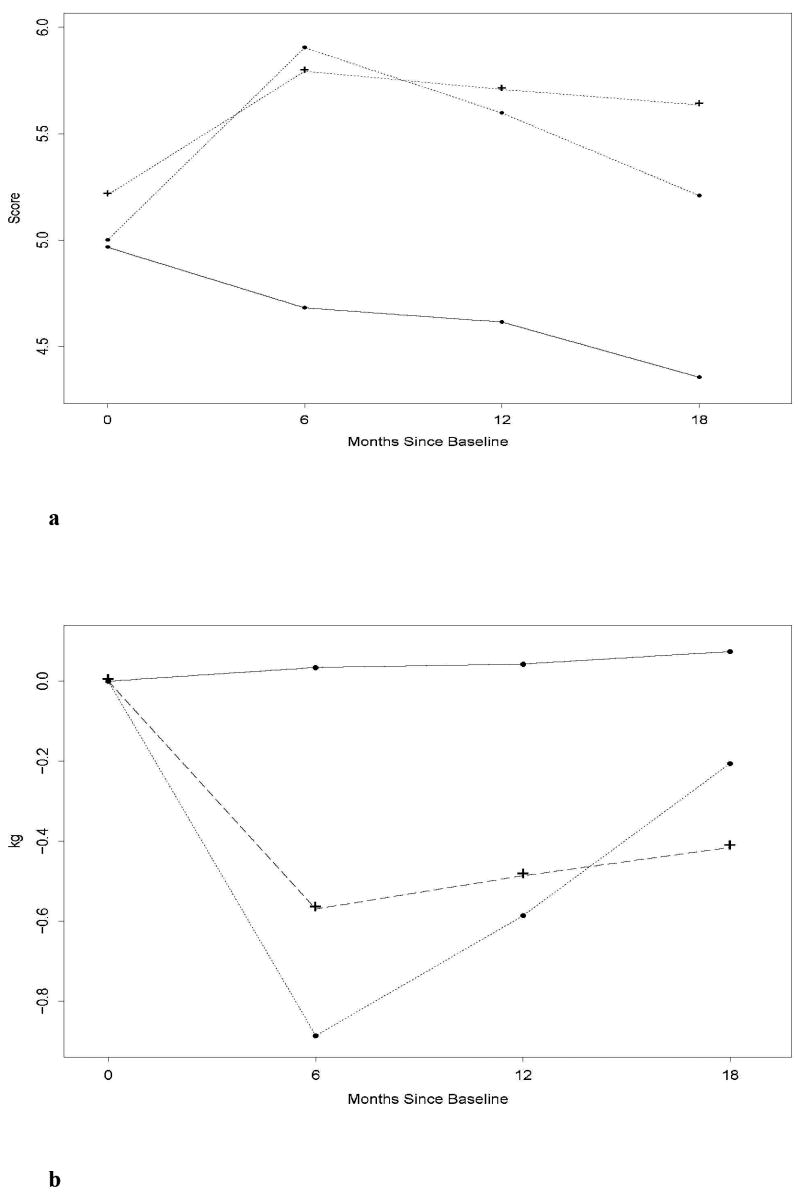

While Tables 2 and 3 present regression coefficients indicating what would occur if self-weighing frequency changed by the same amount across all three groups, Figure 1a shows the actual change in self-weighing frequency within each group, and Figure 1b shows the effect of these changes upon realized weight regain. The Internet group increased their self-weighing frequency by a full unit and the face-to-face group increased by about half a unit, compared with a slight decline in the control group. As shown in Figure 1b, these increases in weighing frequency resulted in a blunting of weight regain in the intervention groups relative to the control.

Figure 1.

a and b. Frequency of self-weighing reported by participants in the Newsletter (—), Internet (--•--), and Face-to-Face (--+--) groups at 0, 6, 12, and 18 months, and the corresponding effect on weight regain.

Changes in Psychological Variables

Change in psychological predictors was also associated with weight regain. Increases in depressive symptoms were associated with weight regain (p<.0001); an increase in BDI scores at follow-up of 3.88 units was associated with .95 kg (95% CI = .676, 1.222) greater weight gain. Likewise, increases in both hunger (p=.003) and disinhibition (p<.0001) were related to greater weight regain: a standard unit increase in hunger resulted in .65 kg (95% CI = .230, 1.073) greater weight regain, whereas the effect of a standard unit increase in disinhibition was almost twice as large at 1.07 kg (95% CI = .600, 1.549).

The entries of Tables 2 and 3 indicate that changes in restraint and changes in weight were negatively associated across all three groups. However, the impact of changes in restraint differed between the two active treatment arms (p=.0002). In particular, the Internet group was quite sensitive to changes in restraint, with a standard unit decrease in restraint associated with additional weight regain of 1.98 kg (95% CI = 1.457, 2.495). The effect of a corresponding change in restraint was attenuated in the newsletter arm (weight change modified by .88 kg; 95% CI = .354, 1.410), and appeared weakest in the face-to-face arm (weight change modified by .46 kg; 95% CI = -.168, 1.088).

While Tables 2 and 3 describe the effects of a hypothetical standard unit change in restraint across all three study groups, Figures 2a and 2b show, respectively, the actual changes in restraint reported in these groups, and their estimated impact on realized weight regain. Despite an initial drop in restraint at the 6-month follow-up that appeared common across groups, the face-to-face group recovered and eventually experienced large increases in restraint, especially in the later months of the program, whereas the newsletter and Internet groups reported continuing decreases in restraint throughout the 18-month study period. Thus, even though the face-to-face group was relatively insensitive to changes in restraint, it was the only one to experience a blunting in weight regain related to this variable.

Figure 2.

a and b. Dietary restraint scores reported by participants in the Newsletter (—), Internet (--•--), and Face-to-Face (--+--) groups at 0, 6, 12, and 18 months and the corresponding effect on weight regain.

Residual Treatment Arm Effects

After adjusting for all other variables in the model, weight regain over the first 6 months was somewhat greater in the Internet group than in the face-to-face group (p=.08), but the average of the two interventions did not differ significantly (p=.92) from the control group. In contrast, during months 6-18, the difference between the two active interventions was not significant (p =.59), while the rate of weight regain accelerated in the newsletter group resulting in a significant difference between the combined intervention groups and the newsletter control (p=.03).

DISCUSSION

STOP Regain provides a unique opportunity to examine predictors of weight regain among a group of successful weight losers. We found that few baseline variables were associated with weight regain; however, changes in both behaviors and psychosocial variables were strongly associated with weight regain over the 18 month program. Among the behaviors, we found that changes in frequency of self-weighing and changes in physical activity had the strongest independent effects on weight regain. However, changes in the psychological variables (depressive symptoms, disinhibition, hunger, and restraint) also exerted strong effects on outcome.

The effect of physical activity on weight regain has been consistently observed in prior studies (Phelan, Wyatt, O’ Hill, & Wing, 2006; Schoeller, Shay, & Kushner, 1997; Weiss et al., 2007). Individuals who maintain higher levels of physical activity achieve larger weight losses at 18 or 30-month assessments in standard behavioral weight loss programs (Tate, Jeffery, Sherwood, & Wing, 2007). Decreases in physical activity have also been found to predict weight regain in the NWCR (McGuire et al., 1999; Raynor et al., 2006).

There has been less research on frequency of self-weighing. In the current analysis, this behavior was a strong predictor of weight regain within the intervention groups but not in the control group. This finding may be due to the fact that daily self-weighing was emphasized in the STOP Regain interventions (Wing et al., 2006), leading to significant increases in the frequency of self-weighing (from several times a week to once daily), and also to the fact that participants in the intervention arms were taught to use the information from the scale to make adjustments in eating and exercise behaviors, thus resulting in strong associations between changes in self-weighing frequency and weight change. In contrast, the control group reported little change in self-weighing frequency; moreover, changes in self-weighing, even if they did occur, had little impact on weight change since these participants had not been taught strategies for modifying their behaviors in response to the scale. Linde et al. (Linde, Jeffery, French, Pronk, & Boyle, 2005) reported that increases in frequency of self-weighing were related to weight loss and weight gain prevention, and changes in frequency of self-weighing were also related to weight regain in the NWCR (Butryn et al., 2007). Although some have been concerned about negative psychological effects of frequent (including daily) self-weighing, a detailed analysis of this issue in STOP Regain found no evidence of a negative effect (Wing, Tate, Gorin, Raynor, Fava, & Machan, 2007).

It is of note that the dietary measures had very little association with weight regain. Difficulties in assessing dietary intake may account for this finding. Other studies have also found that changes in diet account for little of the variance in weight regain (Jeffery et al., 2003; Leermakers, Perri, Shigaki, & Fuller, 1999; McGuire et al., 1999; Wadden, Vogt, Foster, & Anderson, 1998).

In this study, changes in psychological parameters were also strongly associated with weight regain. Increases in depressive symptoms, disinhibition, and hunger were all related to greater weight regain, with particularly strong associations between increases in disinhibition and weight regain. Although the BDI scores in this study were very low at baseline, and even those who gained weight had relatively small increases on this scale, these findings suggest that negative affect and tendencies to uncontrolled eating may be associated with problems in the long term maintenance of weight loss. Behavioral weight control programs teach participants to identify and try to change negative thoughts and to plan ahead to prevent lapses from becoming relapses. Those individuals who practice these skills may be better able to deal effectively with periods of overeating or slips from the program. Higher baseline levels of depressive symptoms and increases in disinhibition have both been associated with weight regain in the NWCR (McGuire et al., 1999) and in other weight loss studies (Niemeier, Phelan, Fava, & Wing, 2007; Vogels, Diepvens, & Westerterp-Plantenga, 2005).

The Restraint scale on the Eating Inventory includes items asking about concerns about weight regain and conscious control of caloric intake. These items relate quite well to the skills taught in the STOP Regain program, e.g. take action if weight gain occurs; use your weight to determine if and when changes in caloric intake are needed. Thus, participants who were able to learn these skills may have been best equipped to maintain their weight losses over the 18-month trial. The finding that the face-to-face group was the only one to show increases in restraint over time suggests that these skills may have been better communicated in this format than in the Internet approach.

The primary finding from STOP Regain reported previously (Wing et al., 2006) was that the face-to-face group experienced less weight regain than the Internet or control group. The current analysis shows that after adjusting for all of the behavioral and psychological variables, the Internet group had slightly (but not significantly) greater initial rates of regain (0-6 months) than face-to-face, but the two intervention groups experienced comparable rates of weight regain between 6 and 18 months which were significantly lower than in the control group. The difference that remains between the two active interventions and the control group after adjusting for changes in the behavioral and psychological variables reflects the effect of unmeasured variables, possibly differences in treatment contact.

Strengths of this study include the ability to comprehensively examine predictors of weight regain in a large sample of highly successful weight losers. Whereas all participants in this trial had been successful in weight loss, and were trying to maintain weight losses of approximately 18% of initial body weight (mean= 18 kg), in the typical analysis of predictors of weight gain following a standard behavioral program many of the participants have never achieved weight loss and the mean weight loss is usually less than half that of STOP Regain participants. In addition, this study allowed us to obtain objective measures of weight, whereas the NWCR data are based only on self-report.

Limitations of the study include the fact that this sample was self-selected and included disproportionate numbers of women and very few minority participants, consequently limiting the generalizabililty of the findings. Moreover, these participants had lost an average of 18 % of their initial body weight; it is not clear whether the findings can be applied to those who experience smaller weight losses. In addition, about one sixth of those who entered the study did not complete all of the 18-month questionnaire measures and were excluded from this analysis. As noted previously, 93% of the participants were weighed at 18 months, but not all of these individuals were also willing to complete the large questionnaire packet. However, our 83% completion rate exceeds that of many weight loss trials. Moreover, we found that those who completed the questionnaires did not differ from non-completers on any variables at baseline except that completers weighed less at baseline.

In conclusion, we found that increases in two behaviors (frequency of self-weighing and physical activity) along with increases in dietary restraint and decreases in disinhibition, hunger, and depressive symptomatology were associated with improved weight loss maintenance. These findings suggest that future programs for weight loss maintenance should focus on modifying these behavioral and psychological variables.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (DK 057413).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at http://www.apa.org/journals/ccp/

References

- Beck AT, Steer RA. Beck Depression Inventory. 1993. San Antonio: Harcourt Brace & Company; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Block G, Hartman AM, Dresser CM, Carroll MD, Gannon J, Gardner L. A data-based approach to diet questionnaire design and testing. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1986;124:453–469. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butryn ML, Phelan S, Hill JO, Wing RR. Consistent self-monitoring of weight: a key component of successful weight loss maintenance. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15(12):3091–3096. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insightful Corporation. S-Plus 8 for Unix User’s Guide. Seattle, WA: Insightful Corporation; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery R, French S. Preventing weight gain in adults: the pound of prevention study. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89(5):747–751. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.5.747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery RW, Wing RR, Sherwood NE, Tate DF. Physical activity and weight loss: does prescribing higher physical activity goals improve outcome? Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78(4):684–689. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.4.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanfer FH, Goldstein AP. Helping people change. New York: Pergamon Press, Inc; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Leermakers EA, Perri MG, Shigaki CL, Fuller PR. Effects of exercise-focussed versus weight focussed maintenance programs on the management of obesity. Addictive Behaviors. 1999;24(2):219–227. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00090-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linde JA, Jeffery RW, French SA, Pronk NP, Boyle RG. Self-weighing in weight gain prevention and weight loss trials. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2005;30(3):210–216. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3003_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire MT, Wing RR, Klem ML, Lang W, Hill JO. What predicts weight regain in a group of successful weight losers? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67(2):177–185. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.2.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niemeier HM, Phelan S, Fava JL, Wing RR. Internal disinhibition predicts weight regain following weight loss and weight loss maintenance. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15(10):2485–2494. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paffenbarger RS, Wing AL, Hyde RT. Physical activity as an index of heart attack risk in college alumni. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1978;108:161–175. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan S, Wyatt HR, O’ Hill J, Wing RR. Are the eating and exercise habits of successful weight losers changing? Obesity. 2006;14:710–716. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raynor DA, Phelan S, Hill JO, Wing RR. Television viewing and long-term weight maintenance: Results from the National Weight Control Registry. Obesity. 2006;14:1816–1824. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoeller DA, Shay K, Kushner RF. How much physical activity is needed to minimize weight gain in previously obese women? American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1997;66:551–556. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/66.3.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stunkard AJ, Messick S. The Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire to measure dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1985;29:71–83. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(85)90010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tate DF, Jeffery RW, Sherwood NE, Wing RR. Long-term weight losses associated with prescription of higher physical activity goals. Are higher levels of physical activity protective against weight regain? Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85(4):954–959. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.4.954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogels N, Diepvens K, Westerterp-Plantenga MS. Predictors of long-term weight maintenance. Obes Res. 2005;13(12):2162–2168. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadden TA, Berkowitz RI, Womble LG, Sarwer DB, Phelan S, Cato RK, et al. Randomized trial of lifestyle modification and pharmacotherapy for obesity. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;353(20):2111–2120. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadden TA, Butryn ML, Byrne KJ. Efficacy of lifestyle modification for long-term weight control. Obes Res. 2004;12(Suppl):151S–162S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadden TA, Vogt RA, Foster GD, Anderson DA. Exercise and the maintenance of weight loss: 1-year follow-up of a controlled clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66(2):429–433. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.2.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss EC, Galuska DA, Kettel Khan L, Gillespie C, Serdula MK. Weight regain in U.S. adults who experienced substantial weight loss, 1999-2002. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(1):34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing RR, Tate DF, Gorin AA, Raynor HA, Fava JL. A self-regulation program for maintenance of weight loss. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(15):1563–1571. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing RR, Tate DF, Gorin AA, Raynor HA, Fava JL, Machan J. “STOP regain”: Are there negative effects of daily weighing? J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75(4):652–656. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]