Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Since the fall of 1999, a new endemic focus of Cryptococcus gattii serotype B infection has emerged on Vancouver Island (Victoria, British Columbia), with infections occurring in both animals and humans. In the human cases, symptoms have manifested as pulmonary nodules, meningitis or both. This organism has added a new nonmalignant cause of pulmonary nodules to the literature, resulting in a change in the management of these nodules by health care professionals.

METHODS:

A search of the number of cases recorded and treated in hospitals of the Vancouver Island Health Authority, along with a review of the literature regarding this emerging organism, was undertaken. The pathology, epidemiology and clinical course of this previously uncommon fungus was determined, and representative cases were chosen for illustration.

RESULTS:

More than 130 cases were recorded in the six-year period from late 1999 to mid-July 2006. The number of cases increased steadily over this period, but appears to be levelling off. Representative cases with medical imaging, along with photos of the pathology, are included. Recommendations for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up are outlined.

CONCLUSIONS:

The emergence of cryptococcal lung and central nervous system lesions on Vancouver Island have made it important to include travel to or residence of the island as part of the history in patients with pulmonary nodules. A registry of patients from Vancouver Island has been established, and it may be of value to include nonisland patients who are found to be infected with this organism.

Keywords: Benign lesions, Infection, Lung, Pathology

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

Depuis l’automne 1999, un nouveau foyer d’endémie par le sérotype B du Cryptococcus gattii a émergé sur l’île de Vancouver (Victoria, Colombie-Britannique), des infections faisant leur apparition chez les animaux et chez les humains. Dans le cas des humains, les symptômes se sont manifestés sous forme de nodules pulmonaires, de méningite ou des deux. Avec cet organisme s’ajoute une cause non maligne de nodules pulmonaires dans les publications médicales, ce qui entraîne un changement de la prise en charge de ces nodules par les professionnels de la santé.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Les auteurs ont entrepris une recherche du nombre de cas enregistrés et traités dans les hôpitaux de la région sanitaire de l’île de Vancouver, de même qu’une analyse bibliographique au sujet de cet organisme émergent. Ils ont déterminé la pathologie, l’épidémiologie et l’évolution clinique de ce champignon auparavant peu commun et choisi des cas représentatifs pour des besoins d’illustration.

RÉSULTATS :

Plus de 130 cas ont été enregistrés pendant la période de six ans s’étalant entre la fin de 1999 et la mi-juillet 2006. Le nombre de cas a augmenté régulièrement au cours de cette période, mais semble plafonner. Les auteurs incluent les cas représentatifs, accompagnés d’imagerie médicale et de photos de la pathologie. Ils exposent les recommandations relatives au diagnostic, au traitement et au suivi.

CONCLUSIONS :

Sur l’île de Vancouver, en raison de l’émergence de lésions cryptococcales des poumons et du système nerveux central, il est devenu important d’inclure les passages ou la résidence sur l’île dans l’anamnèse des patients atteints de nodules pulmonaires. Un registre des patients provenant de l’île de Vancouver a été créé, et il peut être utile d’y inclure les patients de l’extérieur de l’île qui sont infectés par cet organisme.

Since the fall of 1999, a new endemic focus of Cryptococcus gattii serotype B (formerly Cryptococcus neoformans var gattii) infection has emerged on Vancouver Island, British Columbia, causing both animal and human disease (some fatal) (1–4). The affected region is along the south-central part of the coast of Vancouver Island. The organism has been cultured from trees and air samples; it appears to grow on the bark of trees, releasing infectious propagules into the air (2). Air concentrations of propagules increase during long dry summers and decrease during rainy winters (KH Bartlett, personal communication). This new focus of infection may be attributed to a recent recombination event. Unlike most isolates, which are of both a and alpha mating types but predominantly sterile, the majority of the Vancouver Island, British Columbia, outbreak strains are exclusively of the alpha mating type and the majority are fertile (4). From the fall of 1999 to the present, more than 130 human cases have been encountered. Most of the patients have been residents of the island, but a few cases have arisen in persons who visited the island only briefly. Pets that visited the island have also become infected. Most patients presented with asymptomatic pulmonary nodules or opacities. The range of cases included pulmonary nodules (single or multiple), meningitis or combined lesions. No cutaneous lesions were recorded. Animals, domestic and wild, terrestrial and aquatic that have been infected include Dall’s porpoises, domestic cats, dogs, ferrets and other animals, including exotics such as a tapir (1,2). Animals presented with head or neck nodules, lymphadenopathy, and nasal or pneumonic signs. The porpoises were washed up on the shoreline dead.

A diagnosis was determined mainly by cytology. Some of the animals were followed with cryptococcal antigen titres during treatment with fluconazole. Unlike the human cases, some of the animals had predisposing conditions that may have lowered their immunity. Many, but not all, of the animals had travelled to the central island (Parksville-Nanaimo area).

Travellers to the San Joaquin (California, USA) valley may acquire Coccidioides immitis lung lesions, and travellers to the St Lawrence River (Massachusetts, USA) and Mississippi River (Minnesota, USA) valleys may acquire similar lesions from Histoplasma capsulatum infection. It is now evident that travellers to Vancouver Island may acquire C gattii lung and central nervous system (CNS) lesions. Enquiry regarding travel to or previous residence in these areas is an important part of patient history when evaluating lung lesions.

On Vancouver Island, the sudden emergence of this new organism has added to the differential diagnosis of lung lesions. Formerly, most lesions found on chest x-ray and/or computed tomography (CT) scan in this region, unless obviously a granuloma or hamartoma, were considered malignant unless proven otherwise by fine needle aspiration biopsy, by surgical excision, or by following the clinical course for two years or longer.

The present article outlines representative pulmonary case studies of cryptococcal infection. It also discusses the epidemiology, microbiology and radiological features, in addition to the pathological appearances, of the disease. The accumulated local experience and management of the outbreak are discussed.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

A retrospective review of patient discharges from acute care hospitals of Vancouver Island from April 1, 1999, to March 31, 2006, was conducted. Initially, only data from the Victoria hospitals (Royal Jubilee Hospital and Victoria General Hospital) of British Columbia were available for the first fiscal year (April 1, 1999 to March 30, 2000). However, when the medical records from all of the island hospitals were consolidated, data were available for the entire geographic area (Vancouver Island). Any discharge with a principal diagnosis of cryptococcal infection was included in the present study (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Data from the Vancouver Island Health Authority on the number of inpatient cases with any diagnosis of cryptococcal infection, from April 1, 1999, to March 31, 2006

| Fiscal year | Pulmonary cryptococcus | Cerebral cryptococcus | Disseminated cryptococcus | Other specified forms of cryptococcus | Unspecified cryptococcus | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999–2000* | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 2000–2001 | 7 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 11 |

| 2001–2002 | 9 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 17 |

| 2002–2003 | 14 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 23 |

| 2003–2004 | 13 | 13 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 27 |

| 2004–2005 | 16 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 22 |

| 2005–2006 | 14 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 26 |

| 2006† | 4 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| Total | 79 | 49 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 139 |

Central and North Vancouver Island Health Authority data were not available;

Data presented are from April 1 to July 13, 2006

It was apparent that there were more patients being diagnosed each year, but levelling in 2006. With increased awareness of this lesion as a possible differential diagnosis, fewer surgical excisional biopsies were being performed in favour of diagnosis by bronchoscopy or transthoracic fine needle aspiration.

Representative cases outlining the presentation of the disease, particularly with reference to pulmonary medicine, surgery, radiology and pathology practices, have been chosen for illustration.

Case 1

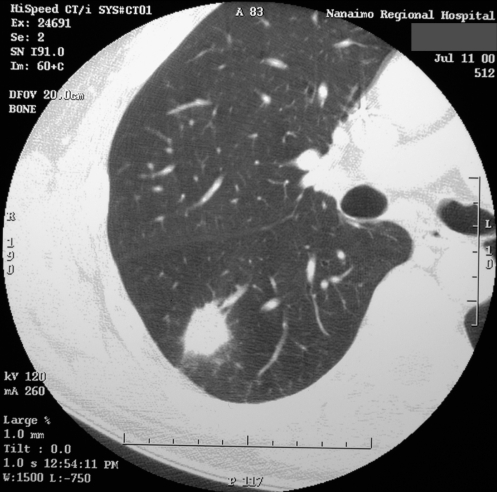

A 54-year-old man was found to have an asymptomatic opacity in the superior segment of the right lower lobe when he was admitted for an acute myocardial infarction (MI). He presented with mild, atypical cardiac symptoms three days after onset and was not a candidate for thrombolysis or angioplasty. He required a pacemaker for bradycardia. After recovery from the MI, a CT scan was performed, demonstrating a 3 cm lesion in the superior segment of the right lower lobe with no adenopathy (Figure 1). He had a 40 pack-year smoking history. There was no other significant medical history. Flexible bronchoscopy showed no endobronchial lesions, and biopsies and washings were nondiagnostic. CT-guided biopsy was negative and did not provide any other nonmalignant diagnosis. He underwent cardiology evaluation preoperatively and was considered to be at reasonable operative risk. Four-and-a-half months after his MI, he underwent an attempted right thoracoscopic wedge resection, which had to be converted to a limited thoracotomy. Excisional wedge biopsy revealed a granuloma, which on permanent sections was found to be a cryptococcal granuloma. He had an uneventful recovery with no cardiac sequelae, and he was discharged in satisfactory condition. No further treatment was advised other than radiological surveillance.

Figure 1).

Case 1. Computed tomography scan of the chest showing a 3 cm lesion in the superior segment of the right lower lobe

Case 2

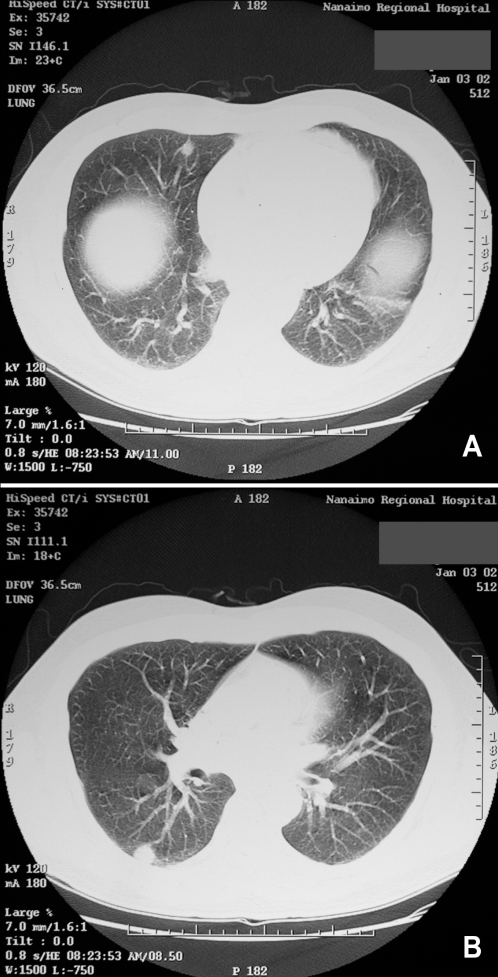

A 62-year-old man presented with right posterior chest pain. Chest x-ray revealed an irregular opacity in the right mid-zone of the lung. He had an 18 pack-year smoking history, but quit 30 years previously. CT scan demonstrated two nodules in the right lung, and possibly a third nodule in the left lung (Figures 2A and 2B). The largest nodule was 1.8 cm in the superior segment of the right lower lobe and was suggestive of malignancy. Tuberculosis (TB) testing was negative, and bronchoscopy revealed no endobronchial lesions. Washings and brushings were negative for malignancy. Cryptococcal serology (antigen latex agglutination test) was nonreactive. He was asymptomatic at the time of surgery. At thoracoscopy, the right lower lobe nodule was completely resected, and the frozen section showed a necrotic granuloma, suspicious for Cryptococcus species. Permanent sections confirmed a cryptococcal lesion. There was no fungal growth from swabs of the lung nodule.

Figure 2).

Case 2. A,B Computed tomography scans of the lungs showing multiple nodules

Case 3

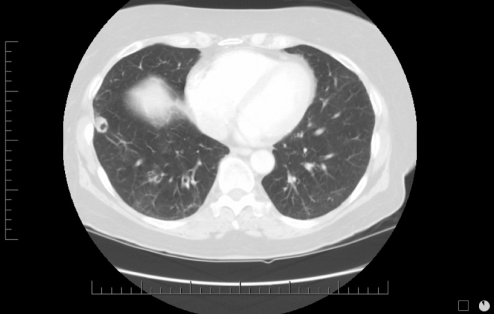

A 69-year-old woman presented with a harsh cough and shortness of breath. She had a 35 pack-year smoking history, but quit 20 years previously. She was exposed to TB working as a nurses’ aide. She had a past history of ulcerative colitis, requiring a total colectomy, but was not receiving immunosuppressive therapy at the time of presentation. Chest x-ray demonstrated a lesion in the right lower lung zone, and CT scan revealed a 1.6 cm cavitating lesion in the anterior segment of the right lower lobe (Figure 3). Flexible bronchoscopy and percutaneous needle biopsy were noncontributory. TB skin testing was equivocal. At thoracoscopy, an excisional wedge biopsy revealed cryptococcal organisms on frozen section, and was confirmed on permanent section. There was no fungal growth from swabs of the lesion taken at the time of surgery. No antifungal therapy was instituted but surveillance by periodic chest x-ray was advised.

Figure 3).

Case 3. Computed tomography scan of the lungs showing a 1.6 cm cavitating lesion in the anterior segment of the right lower lobe

Case 4

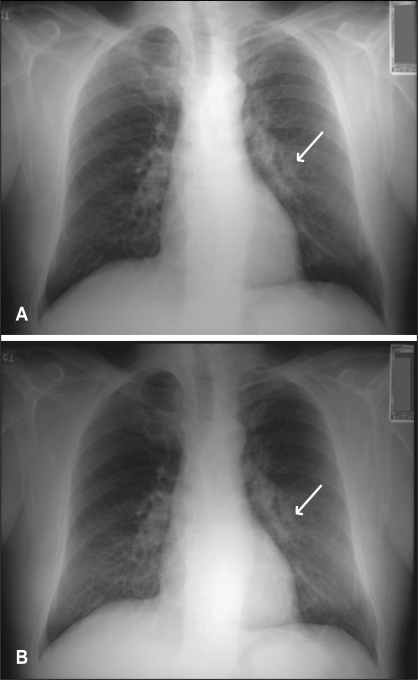

A 65-year-old man was referred with mild recurrent hemoptysis. He was otherwise healthy. He had a 45 pack-year smoking history, but quit 15 years previously. He worked as a painter. Chest x-ray revealed a left hilar opacity, likely in the anterior segment of the left upper lobe (Figure 4A). Flexible bronchoscopy was carried out. No endobronchial lesions were seen. Washings were done, and material was sent for cytology and culture. The patient left for a holiday in Germany the next day against medical advice. A result of cryptococcal infection was reported within a week. In the meantime, the patient had become ill in Germany and was admitted to a German hospital with a diagnosis of meningitis. The results of the bronchoscopy was transmitted to the German physicians, and treatment with fluconazole was instituted. The patient made a full recovery within two weeks and returned to Canada. He was maintained on fluconazole for several months, and the opacity in the left upper lobe was resolving (Figure 4B). At follow-up seven months later, the patient was asymptomatic and his chest x-ray was normal.

Figure 4).

Case 4. A Chest x-ray showing a left hilar opacity (arrow). B Chest x-ray after six months of antifungal therapy, showing resolution of the opacity (arrow)

DISCUSSION

Cryptococci are encapsulated basidiomycetous yeasts that are important opportunistic human pathogens. Transmission is by exposure to an aerosolized inoculum, the infectious propagule being either the basidiospore of the perfect (sexual) form (Filobasidiella neoformans) or the dessicated yeast (5–7). C neoformans is a ubiquitous yeast, whereas C gattii, recently identified as a distinct species (8), and formerly called C neoformans var gatti, has a restricted geographic distribution with a capacity to infect immunocompetent individuals. The main endemic zone of C gattii is in subtropical regions of Australia, where it is strongly associated with eucalyptus trees and produces disease in both koala bears and humans (9). The organism proliferates in decaying eucalyptus wood and has been grown from eucalyptus trees planted in other continents (10). More recently, isolated cases have been found in India, Singapore, Greece, Brazil and Columbia (11–14).

A recent report from Vancouver regarding cryptococcal infections at Vancouver Hospital included three immunocompetent patients who had travelled to Vancouver Island (15).

Local experience supports the suggestion that C gattii is a more virulent organism than C neoformans, infecting immunocompetent hosts and being somewhat resistant to antifungal therapy (16–19).

The emergence of this outbreak of pulmonary lesions due to C gattii has caused many health care professionals to revise their approach to the investigation and management of these lesions. In Canada, most pulmonary lesions, symptomatic or not, are considered neoplastic until proven otherwise. Travel history is important to determine the possibility of coccidiomas or histoplasmomas. Now, travel to Vancouver Island, a popular destination for Canadian, American (approximately 1.2 million tourists annually), European and Japanese tourists, will be important for diagnosing people living elsewhere who develop single or multiple lung opacities, or cryptococcal meningitis.

Although there are no specific imaging characteristics of cryptococcal pulmonary nodules, they have been found to vary in number from one to more than 10. The nodules are usually 6 mm to 20 mm in diameter, and are homogeneous on CT without low attenuation, calcification and, rarely, cavitation (20). Serology is of little value.

Cryptococcus organisms have highly characteristic morphology, including a mucicarmine-positive capsule, and are detected on percutaneous fine needle aspirates, in bronchial washings or occasionally in transbronchial biopsies. Distinction between C neoformans and C gattii cannot be made by morphology or by immunohistochemistry, but depends on serotyping. The excisional lung biopsies contained one or more firm nodules with a whitish or yellow-brown cut surface (sometimes mucoid). The diagnosis was often established by a scrape smear or imprint. Histologically, all of the nodules showed a central necrotic zone (or zones) in which the ghosted outlines of alveoli were discernible. Organisms were usually readily visible in the necrotic zone, but not always numerous. The organisms were usually confined to the necrotic zone (Figures 5A and 5B). The necrotic zone was delineated by macrophages that were sometimes palisaded and sometimes foamy. Most cases showed a palisade of eosinophilic macrophages surrounding the necrotic area, and a further thin layer containing a mixture of lymphocytes, plasma cells and fibroblasts. Foamy histiocytes were present in 11 of 17 open lung biopsies. In these samples, the foamy histiocytes were abundant in five cases (29%), forming collections outside the granuloma and filling the air spaces.

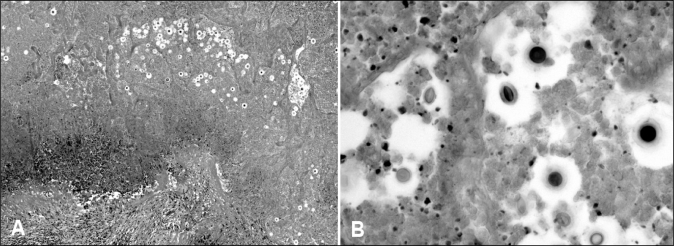

Figure 5).

A Photomicrograph of a necrotic lung nodule containing multiple cryptococci with haloes in the necrotic debris. The granulomatous border of the nodule is visible on the lower left-hand side (hematoxylin and eosin stain). B Photomicrograph of cryptococci within the necrotic debris. Some organisms are round and some are oval. The mucinous capsules are clearly seen in the organisms on the lower right-hand side of the image (hematoxylin and eosin stain, original magnification ×400)

On frozen section, the abundant foamy macrophages were misdiagnosed once as clear cell carcinoma, and on other occasions, raised the question of a clear cell carcinoma, particularly when the necrotic zone was not included in the section. One case, likely an early or recent infection of C gattii infection, showed several tiny foci of necrosis and a mixed response of macrophages, eosinophils, lymphocytes and plasma cells. The fungi in that case were not localized to the centre of the lesion but were scattered throughout the macrophages. One case of C gattii infection occurred coincidentally with a bronchioloalveolar cell carcinoma. Another case had metastatic colon cancer to the lung with a coincidental cryptococcal lung lesion. This concurrence makes ongoing monitoring very important when there are multiple lung opacities on imaging. Also, if immunosuppressive chemotherapy is given as in the latter case, then careful surveillance and perhaps antifungal pro-phylaxis may be required. All excised lesions are cultured to determine whether there are any viable organisms in the lesions, but cultures often fail to grow. This information may help decide whether to offer the patient antifungal therapy postresection. In the case of a fully resected solitary lesion or asymptomatic multiple nodules where organisms are found but fail to grow, antifungal therapy is generally not recommended. Careful evaluation for any CNS symptoms must be performed, and spinal fluid tested if CNS involvement is suspected. If a lesion is fully resected and the patient is otherwise at no particular risk, then only periodical surveillance is necessary. To date, no cases of recurrent lesions have been reported once successfully treated. Because we are seeing more cases of these lesions, fewer thoracoscopic or open biopsies are required to establish a diagnosis.

The emergence of cryptococcal lung and CNS lesions on Vancouver Island have made it important to include travel to or residence of the island as part of the history when evaluating patients with pulmonary nodules. A registry of patients from Vancouver Island has been established, and it may be of value to include nonisland patients who are found to be infected by this organism.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stephen C, Lester S, Black W, Fyfe M, Raverty S. Multispecies outbreak of cryptococcosis on southern Vancouver Island, British Columbia. Can Vet J. 2002;43:792–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lester SJ, Kowalewich NJ, Bartlett KH, Krockenberger MB, Fairfax TM, Malik R. Clinicopathologic features of an unusual outbreak of cryptococcosis in dogs, cats, ferrets, and a bird: 38 cases (January to July 2003) J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2004;225:1716–22. doi: 10.2460/javma.2004.225.1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kidd SE, Hagen F, Tscharke RL, et al. A rare genotype of Cryptococcus gattii caused the cryptococcosis outbreak on Vancouver Island (British Columbia, Canada) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:17258–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402981101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fraser JA, Subaran RL, Nichols CB, Heitman J. Recapitulation of the sexual cycle of the primary fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii: Implications for an outbreak on Vancouver Island, Canada. Eukaryot Cell. 2003;2:1036–45. doi: 10.1128/EC.2.5.1036-1045.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen J, Perfect JR, Durack DT. Cryptococcosis and the basidiospore. Lancet. 1982;1:1301. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)92861-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ellis DH, Pfeiffer TJ. Ecology, life cycle, and infectious propagule of Cryptococcus neoformans. Lancet. 1990;336:923–5. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)92283-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sorrell TC. Cryptococcus neoformans variety gattii. Med Mycol. 2001;39:155–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kwon-Chung KJ, Boekhout T, Fell JW, Diaz M. Proposal to conserve the name Cryptococcus gattii against C. hondurianus and C. bacillisporus (Basidiomycota, Hymenomycetes, Tremellomycetidae) Taxon. 2002;51:804–6. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krockenberger MB, Canfield PJ, Malik R. Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii in the koala (Phascolarctos cinereus): A review of 43 cases of cryptococcosis. Med Mycol. 2003;41:225–34. doi: 10.1080/369378031000137242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vilcins I, Krockenberger M, Agus H, Carter D. Environmental sampling for Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii from the Blue Mountains National Park, Sydney, Australia. Med Mycol. 2002;40:53–60. doi: 10.1080/mmy.40.1.53.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Banerjee U, Datta K, Majumdar T, Gupta K. Cryptococcosis in India: The awakening of a giant? Med Mycol. 2001;39:51–67. doi: 10.1080/mmy.39.1.51.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor MB, Chadwick D, Barkham T. First reported isolation of Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii from a patient in Singapore. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:3098–9. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.8.3098-3099.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Velegraki A, Kiosses VG, Pitsouni H, Toukas D, Daniilidis VD, Legakis NJ. First report of Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii serotype B from Greece. Med Mycol. 2001;39:419–22. doi: 10.1080/mmy.39.5.419.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Callejas A, Ordoñez N, Rodriguez MC, Castañeda E. First isolation of Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii, serotype C, from the environment in Colombia. Med Mycol. 1998;36:341–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoang LM, Maguire JA, Doyle P, Fyfe M, Roscoe DL. Cryptococcus neoformans infections at Vancouver Hospital and Health Sciences Centre (1997–2002): Epidemiology, microbiology and histopathology. J Med Microbiol. 2004;53:935–40. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.05427-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peachey PR, Gubbins PO, Martin RE. The association between cryptococcal variety and immunocompetent and immunocompromised hosts. Pharmacotherapy. 1998;18:255–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fisher D, Burrow J, Lo D, Currie B. Cryptococcus neoformans in tropical northern Australia: Predominantly variant gattii with good outcomes. Aust N Z J Med. 1993;23:678–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1993.tb04726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lehmann PF, Morgan RJ, Freimer EH. Infection with Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii leading to pulmonary cryptococcoma and meningitis. J Infect. 1984;9:301–6. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(84)90772-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lui G, Lee N, Ip M, et al. Cryptococcosis in apparently immunocompetent patients. QJM. 2006;99:143–51. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcl014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zinck SE, Leung AN, Frost M, Berry GJ, Müller NL. Pulmonary cryptococcosis: CT and pathologic findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2002;26:330–4. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200205000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]