Abstract

Accurate system modeling in tomographic image reconstruction has been shown to reduce the spatial variance of resolution and improve quantitative accuracy. System modeling can be improved through analytic calculations, Monte Carlo simulations, and physical measurements. This work presents a novel measured system model and incorporates this model into a fully 3-D statistical reconstruction method. Empirical testing of the resolution versus noise benefits reveal a modest improvement in spatial resolution at matched image noise levels. Convergence analysis demonstrate improved resolution and contrast versus noise properties can be achieved with the proposed method with similar computation time as the conventional approach. Images reconstructed with the proposed model contain correlated noise structures which are difficult to characterize with accepted NEMA noise metrics.

Index Terms: fully 3-D reconstruction, system modeling, point spread function, PET

1. INTRODUCTION

This work presents a practical method to improve the system model in fully 3D positron emission tomography (PET) imaging and evaluates the performance of this more accurate system model. Numerous efforts have explored accurate system models for PET reconstruction [1, 2]. In general, the system model for a PET tomograph can be factorized into multiple components such as the geometric projection matrix (basis for all conventional models), attenuation correction factors, detector sensitivity factors, and detector blurring [3]. This work refines the detector blurring component for a clinical whole-body system through measurements of point sources. We simplify this blurring component to a linear operation that can be quickly applied to the current geometric projection matrix.

This work offers several novel developments beyond our previous efforts to improve system modeling. Specifically, here A) we empirically measure the point spread function (PSF), B) match the PSF to the geometric projector, C) apply the PSF to a fully-3D reconstruction method, and D) propose novel evaluation studies. Along with demonstrated modest resolution and contrast improvements, perhaps the most compelling results show that careful attention must be paid to the noise structure in images reconstructed with a PSF model.

2. POINT SPREAD FUNCTION MODEL

We have previously performed Monte Carlo simulations to evaluate the PSF of modern PET tomographs [4]. For fully 3-D PET, the PSF could be described as a seven dimensional function, with 4 dimensions to describe the blurring in the 4-D data space dependent on the source location in 3-D object space. Our simulations demonstrated that the majority of the blurring occurs in the radial dimension because of the parallax error in cylindrical scanners. This error is a result of increasing inter-crystal penetration and scatter towards the edge of the transaxial FOV. Simulations also demonstrated that the detector blurring kernel shape is most dependent on the radial location of the source. To maintain a practical reconstruction computation time, we decided to use a simplified PSF which models these two dominant dimensions.

The PSF was modeled as a 2-D function S which blurs across radial bins and is variant in the radial location. The geometric projection matrix, P̃, which analytically calculates the intersection of each detection line-of-response with voxels, is modified to form the complete system model P as

| (1) |

for a system with N total measurements.

2.1. Measurement of Point Spread Function

We measured the PSF with a 15µCi Na22 point source of size ~0.25mm diameter embedded in Lucite. Our previous work demonstrated that the Na22 positron range is close enough to F18 to perform system response measurements and that non-collimated sources are capable of characterizing radial blur without degradation from azimuthal contributions [5].

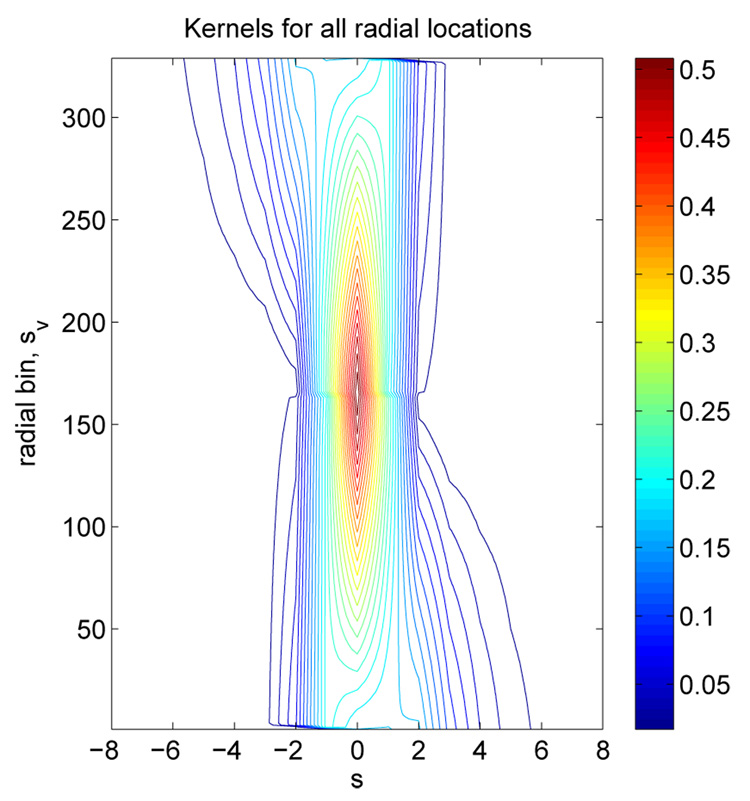

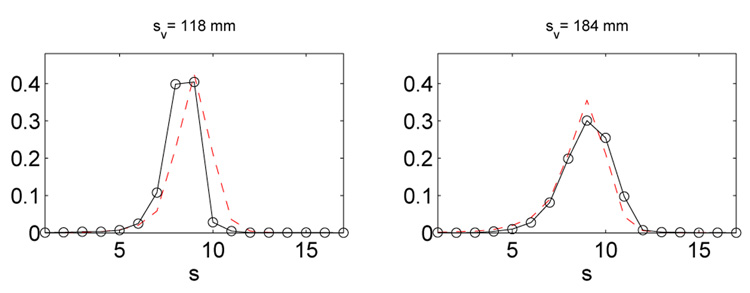

We acquired measurements of the Na22 point source positioned at 14 locations in the FOV on the GE Discovery DSTE PET/CT scanner. The profile through the measured data at a fixed azimuthal angle provided the radial response for a given location. We parameterized the radial response from 12 of these measurements with their discrete cosine transform (DCT) coefficients. The linear fit of these coefficients provided the DCT at all radial positions in the field of view. The inverse DCT at each position provided extrapolated radial blurring kernels. Figure 1 presents the radial blurring kernels which blur in the radial direction s dependent on radial location sv. To provide a independent confirmation of this parameterized model, we compared the model with 2 measured responses which did not contribute to the model. Figure 2 presents independent radial profiles from separate measurements and from the parameterized PSF. The close match provides confidence in the accuracy of the parameterized model. The measured PSF is similar in shape and extent to the 2D PSF we simulated in previous work [4].

Fig. 1.

Radial blurring kernel extrapolated to all radial positions

Fig. 2.

Measured radial profiles (solid) and parameterized radial profiles (dashed) at positions 118mm and 184mm from center of field of view

2.2. Matching Complete System Model with Measurements

The point spread function defining the radial blur of the system at different radial locations was further refined to match the geometric projector. We used an accurate distance-driven projector which models the exact location of the detection lines of response (LOR) [6]. We wanted to ensure that the PSF component when applied to the LOR projector matched actual measurements. We minimized the weighted least squares error of the complete system model and the measurement of the point source at the most extreme radial location. The matched point spread function, Ŝ, was determined as

| (2) |

where yi is a measurement of N total measurements, image x of the point source at a known location, and the forward operation P, which is a function of S. The weights W are defined as the inverse of the variance of measurements; since the data is well modeled as Poisson, Wi = 1/yi, when yi ≠ 0, and Wi = max(y), when yi = 0. Equation(2) was solved with the Newton-Raphson algorithm.

The optimal solution Ŝ was basically identical to the original parameterized S. These results were anticipated considering that our current geometric projector is fairly accurate and requires no radial repositioning interpolation. Geometric projectors which are potentially faster operators at the expense of reduced accuracy might benefit from this weighted least squares refinement step.

We applied the complete system model (1) in a fully 3D ordered subset expectation-maximization (OSEM) reconstruction algorithm. The proposed Ŝ modified the forward and back projection operation during each image update.

3. EVALUATION METHODS

We acquired fully 3D data from 3 phantoms on the GE Discovery STE. For these studies, all corrections were applied to the data inside the iterative loop of OSEM essentially preserving the Poisson statistics of the measurements. We compared OSEM with the accurate line-of-response projector (OSEM+LOR) with our proposed PSF reconstruction (OSEM+LOR+PSF).

3.1. Line Source Phantom

Resolution was evaluated with a custom elliptical phantom (30cm long axis, 22cm short axis, and 18cm deep) with 8 parallel line sources (12cm long, 0.8mm internal diameter). The line sources were filled with F18 and either A) imaged in air or B) imaged with a warm uniform activity concentration background with a roughly 200:1 line to background ratio. The phantom was positioned in the upper half of the scanner bore to evaluate transaxial resolution at radial locations ranging from the center to the edge of the scanner.

3.2. NEMA IQ Phantom

Contrast was evaluated with the NEMA IQ body phantom consisting of a large semi-cylindrical chamber containing six hot spheres with diameters 10, 13, 17, 22, 28, and 37mm. The phantom had an 4:1 sphere to background activity ratio.

4. EVALUATION RESULTS

We present results from volumetric reconstructions with 256×256 voxels per slice using 28 subsets for each iteration. The addition of our PSF model to OSEM+LOR increased the reconstruction time by 3.2%.

4.1. Line Source Phantom

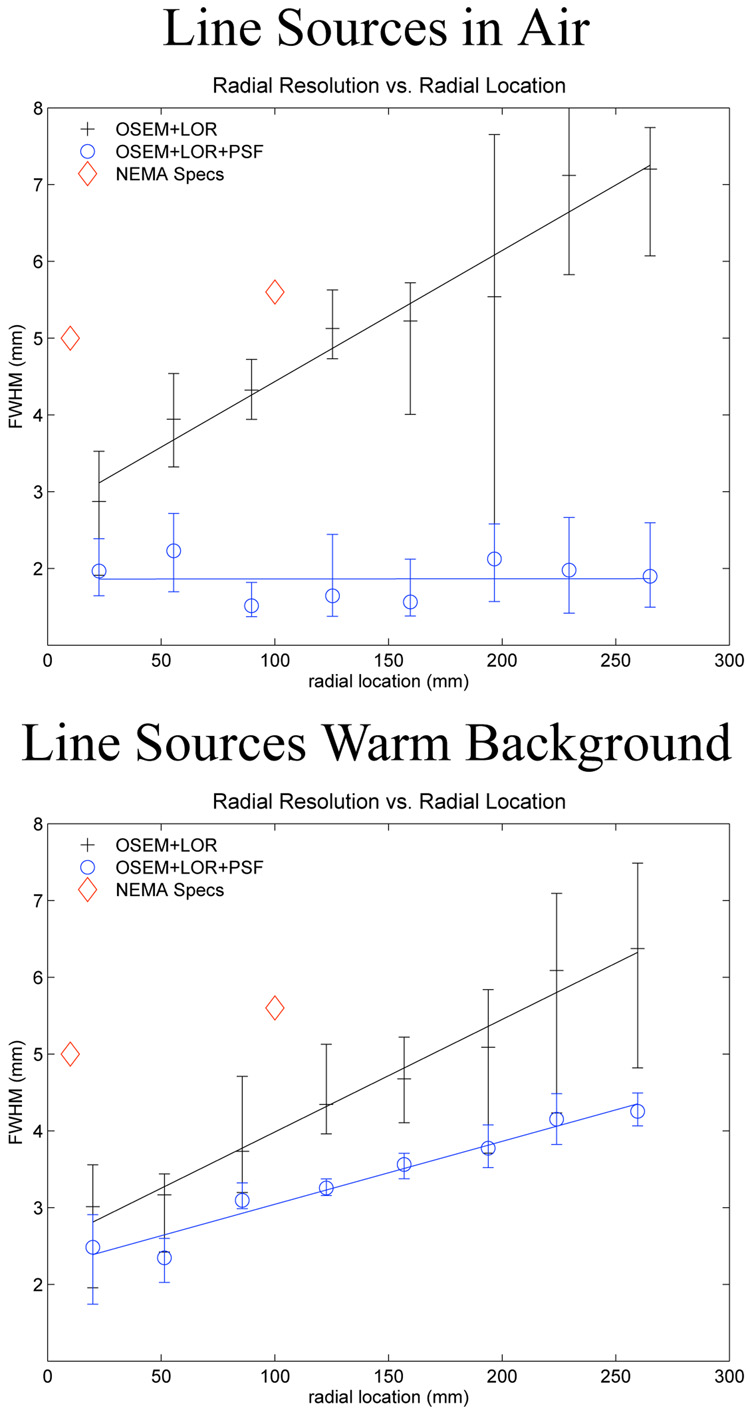

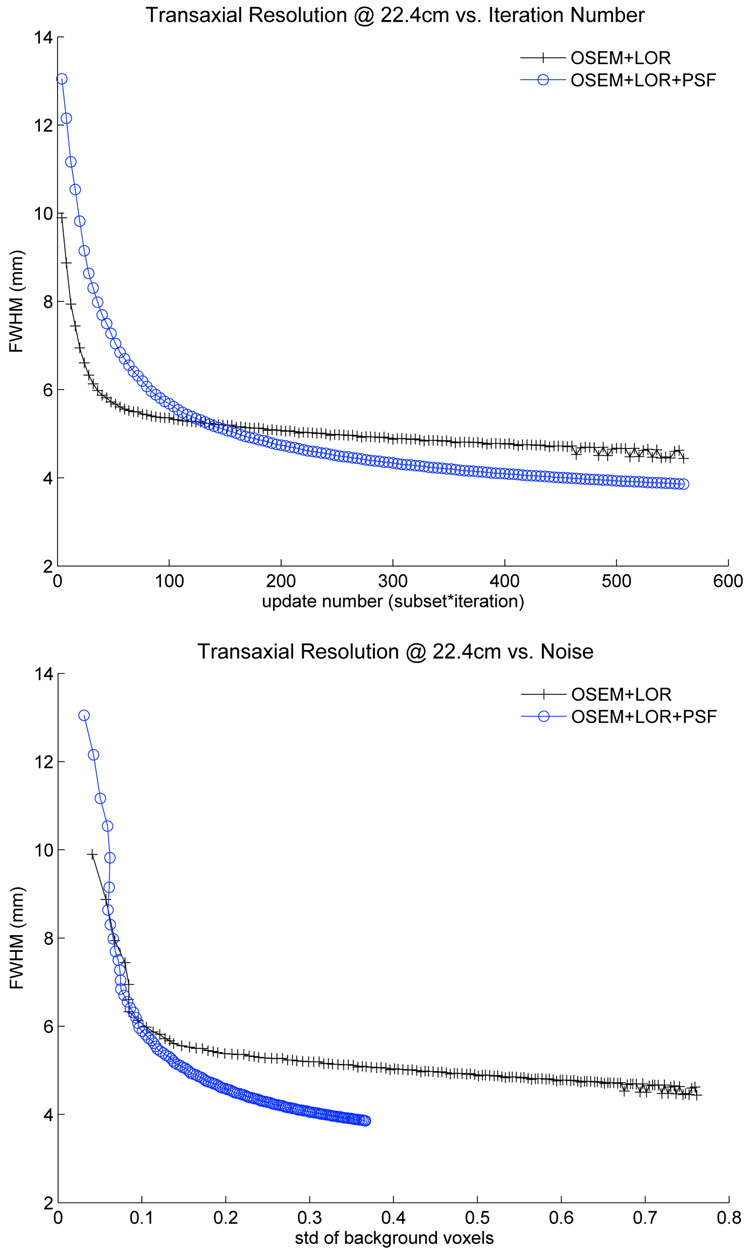

The full width half maximum (FHWM) measured from the line source data appear in figure 3. When the line sources are measured in air, the proposed PSF model resulted in 2mm radial resolution at all locations in the FOV. These results are not reproducible when the line sources are in a more realistic imaging scenario surrounded by a scattering medium and activity. When measured with a warm background, the radial resolution degraded to 2.5mm to 4mm and was dependent on radial location. Increasing the number of iterations to 20 did not dramatically improve the resolution with the PSF and the resolution remained spatially variant (albeit not as spatial variant as OSEM+LOR). It is worth noting that the the line sources in air resolution values are highly dependent on pixel size; the final resolution can be reduced by simply reducing the reconstructed pixel size. Figure 4 presents the resolution metric 22.4cm from the center of transaxial FOV versus image update and versus standard deviation in the background voxels. The FWHM of the PSF method takes longer to converge to a final value than OSEM and appears to have resolution improvements at matched background noise.

Fig. 3.

Radial resolution versus location with first row from line sources in air, second row from line sources in warm background after 10 iterations. Error bars denote the range of FWHM values across 8 neighboring transaxial slices which contribute to mean FWHM.

Fig. 4.

Resolution versus image update and versus standard deviation in background voxels measured from line sources in warm background. All reconstructions updated to 20 iterations, 28 subsets, no post filter and 1.37 mm/pixel.

4.2. NEMA IQ Phantom

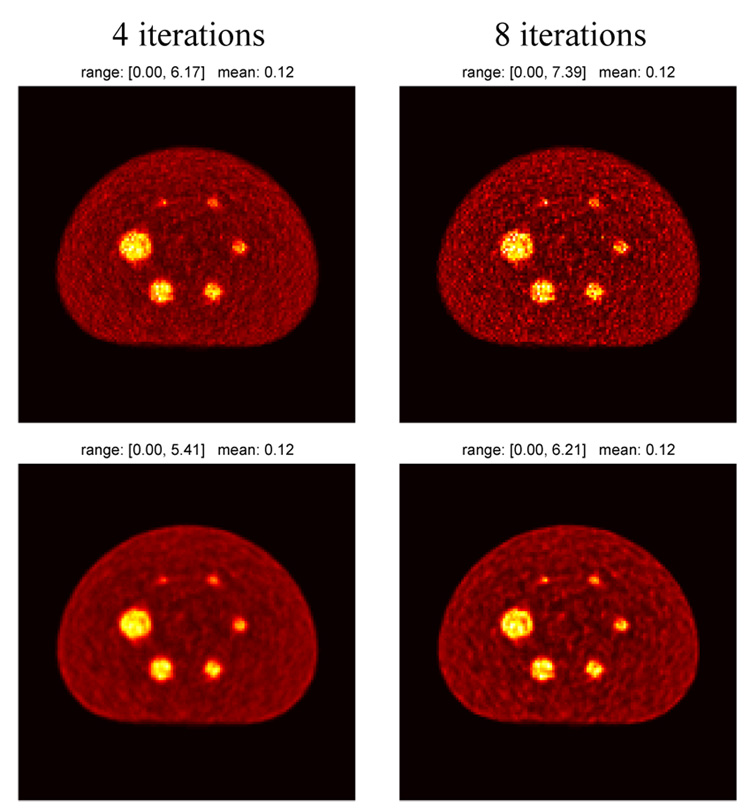

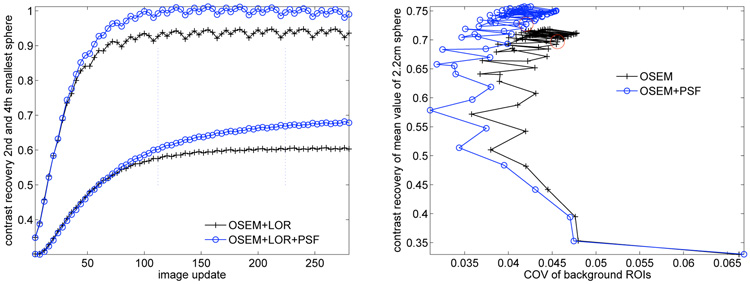

Figure 5 presents images of the NEMA phantom. Visual inspection reveals a different noise structure between the two methods. Figure 6 presents contrast recovery values for images that have been post-filtered with a 2D 7mm FWHM Gaussian filter and a simple triangular axial filter, to mimic a common clinical setting. As with the resolution results, the PSF algorithm appears to require more iterations to reach a final value.

Fig. 5.

NEMA IQ phantom reconstructed with OSEM (first row) and OSEM with PSF (second row). Images are presented after iteration number in headingwith no post-filtering. (2.73 mm/pixel)

Fig. 6.

A) Contrast recovery of maximum value of two spheres versus image update. The vertical lines mark the end of 4 and 8 iterations. B) Contrast recovery of 2.2cm sphere versus coefficient of variation (COV) in background with red circles marking end of 4th iteration.(2.73 mm/pixel, 7mm post-filter).

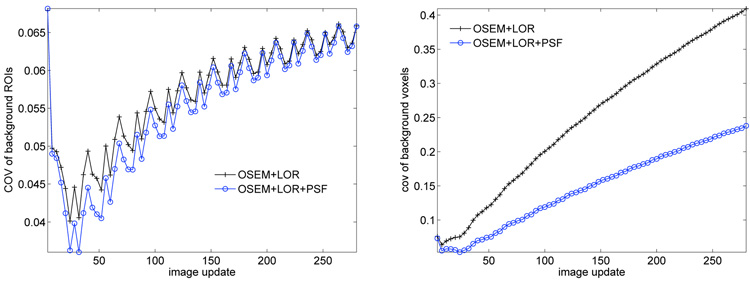

The last row of figure 6 plots the contrast recovery of a sphere versus the coefficient of variation (COV) of the mean value of background regions of interest (ROIs). The COV of background ROIs is computed according to the NEMA standard and provides a sense of the noise level in the image (addresses the quantitative error in the mean value of ROIs). It should be stressed that thorough evaluation of the benefit of a PSF in the reconstruction requires multiple noise metrics. Figure 7 presents the NEMA COV and the COV of all background voxels versus iteration number and highlights that these reconstruction methods have similar “noise” with the first metric and very different noise properties with the second metric.

Fig. 7.

COV in mean value of 60 background ROI’s versus image update and COV in all pixels in background ROI’s versus image update.(2.73 mm/pixel, no post-filter).

5. CONCLUSION

We have measured the PSF of a whole body system and applied the PSF in practical fully-3D reconstruction method. Results from measured phantom studies demonstrate 2mm spatially invariant resolution for the clinically unrealistic scenario of line sources in air. When line sources were positioned in background activity and medium, the proposed method offers modest resolution improvements over conventional OSEM at matched noise levels. Contrast versus noise improvements were demonstrated with the NEMA IQ phantom. Careful assessment of noise properties is required to evaluate these PSF algorithms and future work will explore performance with clinically relevant reconstruction parameters and multiple noise metrics to determine the genuine contrast/resolution versus noise gains of the proposed method.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We are thankful for image reconstruction conversations with S. Ross, C. Stearns, S. Wollenweber, E. Asma and R. Manjeshwar.

Supported by NIH grants HL086713, CA115870, and CA74135 and a grant from GE Healthcare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Liang Zhengrong. Detector response restoration in image reconstruction of high resolution positron emission tomography. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 1994 June;vol. 13(no 2):314–321. doi: 10.1109/42.293924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Staelens Steven, D’Asseler Yves, Vandenberghe Stefaan, Koole Michel, Lemahieu Ignace, Van de Walle Rik. A three-dimensional theoretical model incorporating spatial detection uncertainty in continuous detector PET. Phys Med Biol. 2004;vol. 49(no 11):2337–2350. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/49/11/015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jinyi Qi, Leahy RichardM, Cherry SimonR, Chatziioannou Arion, Farquhar ThomasH. High-resolution 3D Bayesian image reconstruction using the microPET small-animal scanner. Phys Med Biol. 1998;vol. 43(no 4):1001–1013. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/43/4/027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alessio Adam, Kinahan Paul, Lewellen Tom. Modeling and incorporation of system response functions in 3D whole body PET. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2006;vol. 25(no 7):828–837. doi: 10.1109/tmi.2006.873222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alessio A, Kinahan P, Harrison RL, Lewellen TK. Measured spatially variant system response for PET image reconstruction. IEEE Nucl. Sci. Symp. and Med. Imaging Conf.; Puerto Rico. 2005. pp. 1986–1990. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manjeshwar RM, Ross SG, Iatrou M, Deller TW, Stearns CW. Fully 3D PET iterative reconstruction using distance-driven projectors and native scanner geometry. IEEE Nucl Sci Symp Conf Record; 2006. pp. 2804–2807. [Google Scholar]