Abstract

Late referral of patients with chronic kidney disease is associated with increased morbidity and mortality, but the contribution of center-to-center and geographic variability of pre-ESRD nephrology care to mortality of patients with ESRD is unknown. We evaluated the pre-ESRD care of >30,000 incident hemodialysis patients, 5088 (17.8%) of whom died during follow-up (median 365 d). Approximately half (51.3%) of incident patients had received at least 6 mo of pre-ESRD nephrology care, as reported by attending physicians. Pre-ESRD nephrology care was independently associated with survival (odds ratio 1.54; 95% confidence interval 1.45 to 1.64). There was substantial center-to-center variability in pre-ESRD care, which was associated with increased facility-specific death rates. As the proportion of patients who were in a treatment center and receiving pre-ESRD nephrology care increased from lowest to highest quintile, the mortality rate decreased from 19.6 to 16.1% (P = 0.0031). In addition, treatment centers in the lowest quintile of pre-ESRD care were clustered geographically. In conclusion, pre-ESRD nephrology care is highly variable among treatment centers and geographic regions. Targeting these disparities could have substantial clinical impact, because the absence of ≥6 mo of pre-ESRD care by a nephrologist is associated with a higher risk for death.

Nephrology care before starting hemodialysis (HD) is an important determinant of health status of patients with ESRD1,2 and is associated with hypoalbuminemia,3 anemia,4 absence of a functioning arteriovenous vascular access,5 reduced quality of life,6 and decreased kidney transplantation.7 Delayed care is associated with progression of kidney disease8,9 and increased mortality after start of HD.10–13 Early nephrology referral for individuals with chronic kidney disease (CKD) is recommended14,15 for creation of an arteriovenous fistula (AVF) 6 mo before the anticipated start of HD.16

Despite these guidelines, incident patients with ESRD frequently present without antecedent nephrology care.17 Differences between treatment center and geographic areas, similar to variations reported for the care of prevalent patients with ESRD, are possible factors that might contribute to variable pre-ESRD care.17–19 If clinically relevant center-to-center and geographic variations in pre-ESRD care exist, then interventions might be designed to reduce the risk for delayed or absent care. This report describes the variable prevalence and clinical consequences for both individual patients and their treatment center populations of delayed pre-ESRD nephrology care in a large population-based sample of incident patients with ESRD.

RESULTS

We studied 30,327 incident patients and excluded 1198 (3.9%) individuals whose initial dialysis dates were outside the study time frame (June 1, 2005, to May 31, 2006) and 98 (0.8%) individuals whose first treatment modality was other than in-center HD. The characteristics of the remaining 29,031 incident patients are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of incident patients that were independently associated with predialysis nephrology care of >6 moa

| Attribute | n (%) | Recommended Predialysis Care (%)b | OR (95% CI)c |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 28,135 | 14,451 (51.3) | |

| Age (yr) | 62.8 ± 15.3 | ||

| 20 to 44 | 3775 (13.4) | 1642 (43.0) | Reference |

| 45 to 64 | 10,787 (38.3) | 5673 (52.6) | 1.01 (0.89 to 1.15) |

| 65 to 84 | 12,305 (43.7) | 6580 (53.5) | 1.19 (1.06 to 1.33) |

| ≥85 | 1266 (4.5) | 573 (45.3) | 1.14 (1.03 to 1.28) |

| Race | |||

| black | 12,854 (44.3) | 6281 (48.9) | 1.00 (0.95 to 1.06) |

| white | 16,177 (55.7) | 8612 (53.2) | – |

| Gender | |||

| female | 13,485 (46.4) | 7029 (52.1) | 1.08 (1.03 to 1.13) |

| male | 15,546 (53.6) | 7864 (50.6) | – |

| DM-ESRD | 12,657 (43.6) | 73,064 (57.7) | 1.50 (1.43 to 1.56) |

| Comorbidity | |||

| ASCVD | 6304 (21.7) | 3552 (56.4) | 1.14 (1.07 to 1.22) |

| HF | 10,155 (35.0) | 5133 (50.6) | 0.83 (0.79 to 0.88) |

| CVA | 3214 (11.1) | 1676 (52.2) | 1.00 (0.93 to 1.07) |

| PVD | 4322 (14.9) | 2390 (55.3) | 1.06 (0.99 to 1.14) |

| amputation | 1051 (3.5) | 540 (53.2) | 1.00 (0.88 to 1.13) |

| No health insurance | 2543 (8.9) | 785 (30.9) | 0.44 (0.40 to 0.49) |

| Not employed | 5743 (19.8) | 2408 (42.0) | 0.79 (0.74 to 0.84) |

| Not ambulatory | 2044 (7.0) | 873 (42.7) | 0.86 (0.76 to 0.97) |

| Unable to transfer | 893 (3.1) | 339 (38.0) | 0.91 (0.76 to 1.08) |

| Needs ADL assistance | 3294 (11.4) | 1486 (45.1) | 0.88 (0.81 to 0.95) |

| Resident institution | 2248 (7.7) | 800 (35.6) | 0.54 (0.49 to 0.59) |

ADL, activities of daily living; ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; HF, heart failure; PVD, peripheral vascular disease.

Percentage of all patients with the row attribute.

Odds ratio adjusted for all factors in table and accounting for within-center correlation of patients.

Predialysis Care and Patient Characteristics

Pre-ESRD nephrology care was reported by 57.8% of all incident patients, was absent for 33.1%, and was missing for 9.1%. The duration of care was greater than 12 mo in 24.1%, 6 to 12 mo in 27.2%, and <6 mo in 6.4%. Recommended care, defined as ≥6 mo of predialysis care, was reported for 14,893 (51.3%) of patients. Older age, female gender, diabetes as a primary cause of ESRD, and atherosclerotic heart disease were independently associated with increased predialysis care, whereas heart failure, having no health insurance and being unemployed 6 mo before start of dialysis, being unable to ambulate, needing assistance with the activities of daily living, and residing in a nursing home were associated with decreased care (Table 1).

Predialysis Care and Stage 4 CKD Care

Patients who received ≥6 mo of predialysis care were more likely to have an AVF (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 4.00; 95% confidence interval [CI] 3.57 to 4.50) to be treated with an erythropoietin-stimulating agent (ESA), have pretreatment dietary counseling, and to have hemoglobin and albumin guideline–based levels (Table 2).

Table 2.

Association between nephrology care of >6 mo and outcomes of predialysis treatmenta

| Attribute | n (%) | Patients with Pre-ESRD Care (n [%]) | Adjusted OR (95% CI)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Survived | |||

| yes | 23,943 (82.5) | 12,734 (53.2) | 1.50 (1.40 to 1.62) |

| no | 5088 (17.5) | 2159 (42.4) | – |

| AVF | 3381 (11.7) | 2781 (84.5) | 4.00 (3.57 to 4.50) |

| AVG | 1648 (5.7) | 1181 (77.7) | 2.23 (1.96 to 2.53) |

| Catheter | 23,822 (82.6) | 10,795 (45.3) | – |

| Hemoglobin >11 g/dl | 7297 (25.1) | 4350 (59.6 | 1.27 (1.20 to 1.35) |

| Predialysis ESA | 8319 (28.7) | 7014 (84.3) | 5.98 (5.48 to 6.52) |

| BMI | |||

| underweight | 1421 (4.9) | 603 (42.4) | 0.97 (0.86 to 1.10) |

| normal | 9181 (31.6) | 4372 (47.6) | – |

| overweight | 7899 (27.2) | 4104 (52.0) | 1.09 (1.02 to 1.16) |

| obese | 5093 (17.5) | 2749 (54.0) | 1.15 (1.06 to 1.24) |

| clinically obese | 2705 (9.3) | 1525 (56.4) | 1.27 (1.15 to 1.39) |

| morbidly obese | 2732 (9.4) | 1540 (56.4) | 1.32 (1.20 to 1.46) |

| Optimal albuminc | 1618 (5.6) | 1095 (67.7) | 1.54 (1.35 to 1.74) |

| Dietary care | 2420 (8.3) | 2154 (89.0) | 5.32 (4.30 to 6.59) |

Predialysis Care and Individual Mortality

There were 5088 deaths (17.8%) during follow-up. Mean ± SD duration of follow-up was 321 ± 102 d, with a median follow-up of 365.2 d and a range from 0 to 423 d. Among those who received recommended predialysis care, 85.5% survived compared with 79.3% of those who did not receive ≥6 mo of nephrology care (OR 1.54; 95% CI 1.45 to 1.64). The survival advantage associated with pre-ESRD nephrology care persisted (OR 1.50; 95% CI 1.40 to 1.62) after controlling for other risk factors. When we further controlled for incident AVF, hemoglobin and albumin levels, ESA use, body mass index (BMI), and dietary counseling, the survival advantage was attenuated (OR 1.31; 95% CI 1.22 to 1.41).

Treatment Center Variations in Predialysis Care

A total of 1641 treatment centers were included in the analysis with a mean ± SD number of incident patients of 18.1 ± 13.1, a median of 15 and a 25th to 75th interquartile range (IQR) between nine and 24 patients. The mean ± SD proportion of patients within a treatment center who received recommended predialysis nephrology care was 48.7 ± 24.1%, with a 25th to 75th IQR from 33.3 to 64.3%. Treatment centers in the lowest quintile of pre-ESRD nephrology care had lower proportions of patients achieving guideline recommended serum albumin and hemoglobin levels, were less likely to have received an ESA or dietary counseling, and had a lower proportion of incident patients with an AVF (Table 3). For each patient care measure, with the exception of BMI (P = 0.1133), the increases in care were clinically and statistically significant (P < 0.001; Table 3).

Table 3.

Association between HD center variations in recommended predialysis care and outcomes

| Treatment Center Attribute | Treatment Center Quintile of Predialysis Care

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lowest | Second | Third | Fourth | Highest | |

| n | 329 | 327 | 326 | 331 | 328 |

| Pre-ESRD nephrology care | 14.8% | 39.6% | 52.7% | 64.4% | 85.0%a |

| AVF | 7.8% | 9.8% | 11.4% | 14.0% | 17.8%a |

| Hemoglobin >11 g/dl | 21.3% | 23.3% | 24.7% | 26.7% | 29.8%a |

| Predialysis ESA | 13.1% | 24.4% | 27.8% | 35.3% | 42.7%a |

| Predialysis dietary care | 4.4% | 6.5% | 9.2% | 10.0% | 11.6%a |

| Albumin target | 2.8% | 4.8% | 6.4% | 6.0% | 6.9%a |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.8 | 28.7 | 28.9 | 29.3 | 29.1 |

| Deaths | 19.6% | 17.7% | 17.2% | 15.4% | 16.1%a |

| SMR | 1.16 | 1.00 | 0.95 | 0.87 | 0.93a |

P < 0.001.

Treatment Center Mortality Was Associated with Predialysis Care

The mean ± SD facility-specific death rate was 17.2 ± 13.8% of all incident patients and the 25th to 75th IQR was between 8.0 and 25.0% of a facility's patients. As the proportion of patients receiving recommended nephrology care increased from lowest to highest quintile of care, the mean facility unadjusted mortality rate decreased from 19.6 to 16.1% (P < 0.001), a relative reduction of 15% and an absolute reduction of 3.5% (Table 3).

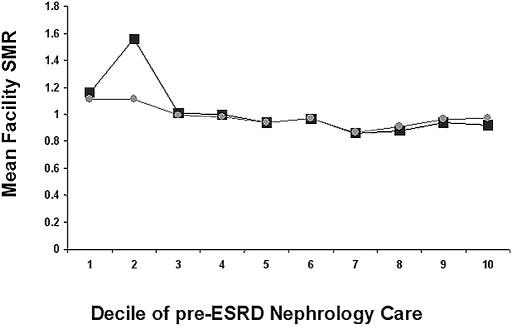

The mean ± SD facility-specific standardized mortality ratio (SMR), the ratio of the actual to predicted deaths in a center, was 0.98 ± 0.79 with a 25th to 75th IQR from 0.50 to 1.36. The mean SMR was higher among treatment centers in the lowest decile of pre-ESRD nephrology care (mean SMR 1.16) and declined in the highest decile of pre-ESRD care (mean SMR 0.92; P = 0.0031; Figure 1). The center-to-center variability risk for death persisted after controlling for patient characteristics and within-center clustering, but, after controlling for incident AVF, hemoglobin and albumin level, BMI at start of therapy, previous ESA use, and dietary consultation, the differences in mean SMR across deciles of care were no longer statistically significant (P = 0.1431; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Facility-specific SMRs by decile of pre-ESRD nephrology care. Squares represent the SMR adjusted for all patient characteristics and circles the SMR adjusted for all patient characteristics and pre-ESRD care (ESA use, incident serum albumin and hemoglobin, BMI, AVF status, and predialysis nutrition consultation).

Geographic Clustering of Treatment Centers with Low Pre-ESRD Care

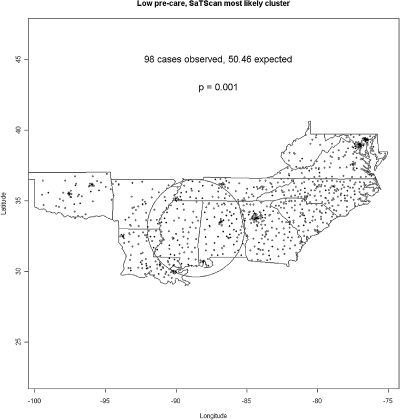

Facilities in ESRD Networks 5, 6, 8, and 11 in the lowest quintiles of pre-ESRD care were not randomly distributed. The map in Figure 2 denotes low pre-ESRD centers as black symbols, and a single, significant circular cluster of low pre-ESRD care centers was located in Alabama and Mississippi. We note that, whereas other clusters are visually apparent, the scan statistic identifies the collection of observed cases least consistent with a null hypothesis of equal risk, even in the presence of a geographically heterogeneous distribution of the at-risk population. The detected circular cluster has a “hole” in the middle with no low-pretreatment centers but a “ring” of high low-pretreatment hospitals around it with one edge seeming to line up with the Mississippi River corridor from New Orleans up to Memphis, the other edge comprising most of the state of Alabama.

Figure 2.

Geographic clustering of low pre-ESRD nephrology care among ESRD treatment centers.

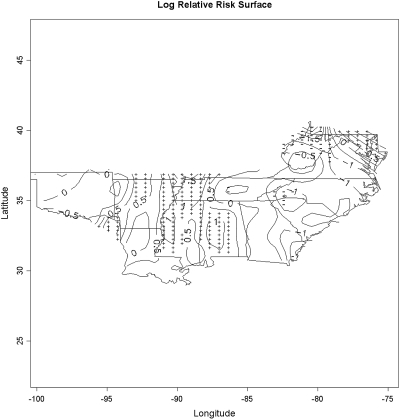

The smoothed relative risk surface in Figure 3 describes the geographic distribution of low-rate centers compared with the rest of the centers. Compared with the results from the circular scan statistic in Figure 2, we observed a ridge of significantly elevated relative risk for low pre-ESRD care centers following the ring noted in the previous paragraph, reaching from western Tennessee with a western “arm” along the Mississippi river corridor and an eastern arm through Alabama.

Figure 3.

Map depicts the contiguous states in ESRD Networks 5, 6, 8, and 13. The map displays the natural logarithm of the estimated relative risk surface for having no predialysis nephrology care. Areas marked by “+” indicate areas significantly increased local prevalence of low pre-ESRD care centers and areas marked by “−” indicate significantly decreased local prevalence of low pre-ESRD centers.

DISCUSSION

Our most important finding was that substantial center-to-center variations in pre-ESRD nephrology care exist and are associated with both increased risk for death for individual patients and increased facility mortality rates. Furthermore, centers with the highest proportions of patients without ≥6 mo of pre-ESRD care are clustered geographically. Although the association between low rates of pre-ESRD nephrology care and increased risk for mortality at the onset of HD has been extensively reported, the nonrandom nature of pre-ESRD nephrology care and its association with treatment center mortality differences has not, and recognition of this variability may be relevant to efforts to improve stage 4 CKD care.

We and others have noted that the increased risk for mortality during the earlier part of the first year of dialysis is associated with pre-ESRD clinical status.20,21 In this study, as the proportion of patients receiving pre-ESRD nephrology decreased, the prevalence of modifiable mortality risk factors at the inception of renal replacement therapy (RRT) increased, with a decrease in proportion of incident patients with an AVF, hemoglobin >11 g/dl, and serum albumin within the target range. Furthermore, these mortality risk factors were increased in prevalence among individual who had received predialysis nephrology care. Thus, it is likely that the relationship among individual patients between first-year mortality after onset of RRT and predialysis care reflects, in part, the admission health status of these patients; however, it is unlikely that all of the increased risk for mortality during the first year of RRT can be attributed to predialysis factors, and variability in ESRD treatment factors, including adequacy of dialysis, changes in vascular access status, hemoglobin levels, and nutritional status, are likely to influence mortality as well. We were unable to account for these latter factors in our analyses.

Factors that might influence the timing of pre-ESRD nephrology care include characteristics of the (1) antecedent kidney disease, (2) patient, (3) physician, and (4) health system where care is delivered.22 Disease-related factors that might account for center-to-center variations in pre-ESRD nephrology care include the prevalence of undetected, asymptomatic CKD in a population, and 15 to 20% of all incident ESRD patients may fall into this pattern of CKD progression.23 Although we are unable to account for our study, the median time spent in stage 3 CKD before ESRD is reported to be >2.5 yr and that in stage 4 CKD >2 yr.24 This suggests that there is ample time before ESRD for detection of CKD and nephrology referral.

Our observations are consistent with previous studies that reported associations between nephrology referral and individual patient characteristics, including cause of kidney disease, comorbidity, and age.25 We extended these observations to include impaired mobility and nursing home residence as factors associated with less pre-ESRD nephrology care. The center-to-center variability in pre-ESRD nephrology care persisted after controlling for patient characteristics (data not shown). Also, the association between pre-ESRD nephrology care and treatment center mortality persisted after accounting for other risk factors.

Physician-related factors might account for the center-to-center variations in care we observed. Winkelmeyer et al.24 found that delayed nephrology care of Medicare and Medicaid patients with CKD was more frequent among general internists. Other physician-related factors that might account for delayed referral include nephrology manpower availability, low detection rates of CKD by primary care physicians among patients with stages 3 and 4 CKD,26 lack of awareness and uncertainty about how to use clinical practice guidelines for CKD,27 and lack of familiarity with high-risk populations for ESRD. Information about these factors is absent from our data.

Health system factors that may influence early nephrology care have largely been considered to govern access to care. Our finding that insurance status and employment 6 mo before the start of dialysis were associated with early referral is consistent with this possibility and with previous studies28–32; however, as with patient characteristics, the center-to-center variability in pre-ESRD nephrology care persisted after controlling for insurance and employment status (data not shown). Another system factor that might account for facility-to-facility variations in pre-ESRD nephrology care is the highly variable compliance among US physicians with guideline-recommended care for chronic diseases. This variability suggests that the variable care we observed may reflect imperfect adoption of guideline recommendations throughout the US health care system.33

Finally, although our results are limited to the geographic extent of our data, the geographic variability in pre-ESRD nephrology care among treatment centers we observed is consistent with extensive reports of geographic variations in care in the US health care system that persist after accounting for patient attributes.34 These variations in care are attributed to misplaced economic incentives, inadequate dissemination of evidence-based practice guidelines, and ambiguities in the state of clinical practice.35 Our analyses do not address the reasons that these variations exist but rather serve to draw attention to their existence and potential relevance to quality improvement interventions for patients with stages 3 and 4 CKD.

Our results suggest that population-based efforts to improve pre-ESRD care might target communities with treatment centers or clusters of centers with low rates of pre-ESRD nephrology care. The ESRD Networks can identify these centers36 and design and implement interventions directed at deficient care.37,38 It is reasonable to suggest that a similar approach to improving pre-ESRD care might be warranted. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) recently awarded contracts to the Medicare Quality Improvement Organizations in 10 states for the period 2008 to 2011 (http://www.cms.hhs.gov/QualityImprovementOrgs) to improve early detection and care of diabetic nephropathy and increasing incident AVF use among Medicare beneficiaries.

The limitations of our report beyond those discussed should be noted. The pre-ESRD care data derived from the CMS 2728 forms are subject to misclassification, have not been validated, and may be entered differentially by poorly performing treatment centers. The strong associations between the reported pre-ESRD care and both health status and subsequent survival of incident patients and that the system uniformly collects mortality data suggest that it is unlikely that individuals lost to follow-up contributed to substantial selection bias. We restricted our analysis to HD patients, and the exclusion of peritoneal and transplant patients may have excluded low-risk patients in some treatment centers. We cannot exclude this possibility but believe that it likely involves a small proportion of incident patients. An additional limitation is that our findings reflect regional variations in overall access to the health care system and patients who did not see a nephrologist were without any health care, confounding the association between nephrologist care. Although we attempted to account for this by controlling for insurance status, it remains possible that residual confounding persists.

In conclusion, pre-ESRD nephrology care among incident patients with ESRD is associated with increased risk for death. Less-than-adequate pre-ESRD care aggregates within treatment centers and geographic regions, which suggests that targeted quality improvement interventions might be warranted in these populations.

CONCISE METHODS

All dialysis treatment centers and patients who were aged ≥20 yr and initiated HD therapy between June 1, 2005, and May 31, 2006 (99.7% of all incident patients) in ESRD Networks 5, 6, 8, 11, and 13 were studied.

Data Collection

De-identified patient information was obtained from the CMS 2728 form, the End Stage Renal Disease Medical Evidence Report Medicare Entitlement and/or Patient Registration form during the years 2005 and 2006. Data used included race, gender, age, BMI, diabetes as primary cause of ESRD, heart failure, atherosclerotic heart disease, peripheral vascular disease, and history of amputation. Individuals were defined as uninsured and unemployed on the basis of their insurance or employment status 6 mo before dialysis.

Predialysis Care

A patient's physician completed CMS 2728 questions on predialysis care. The CMS 2728 form asks, “Before ESRD therapy: Was the patient under the care of a nephrologist?” Responses were “yes” and “no.” Those who replied “yes” then indicated the duration of care as 6 to 12 mo or > 12 mo. We categorized pre-ESRD nephrology care as present when the answer was either 6 to 12 mo or >12 mo” and absent otherwise.

AVF for first HD was defined as a “yes” answer. Additional aspects of pre-ESRD care recorded included pre-ESRD ESA use and dietary consultation. Clinic staff recorded laboratory values for albumin and hemoglobin collected within 45 d before the start of ESRD.

Pre-ESRD albumin status was defined as optimal when the serum albumin was ≥4.0 g/dl by the bromcresol green method or 3.7 g/dl by the bromcresol purple method. When the analytic method for albumin was missing, we used values ≥4.0 g/dl to define optimal albumin. Anemia care was defined as optimal when the reported hemoglobin was ≥11.0 g/dl.

Follow-up

Follow-up by the Network for each patient began on the day of first dialysis and continued until August 2006. Patients were censored at the time of transplantation, transfer from the treatment center, death, or end of the study.

Statistical Analysis

We examined the independent associations between predialysis care and AVF status with mortality using logistic regression, controlling for clustering within treatment centers with generalized estimating equations (GEE). The SAS GENMOD was used to perform the generalized estimating equation regression analysis, which produced clustered robust SEs that correct for within-facility correlation.39

We examined the independent contribution of ESRD treatment centers to the risk for mortality after controlling for fixed patient characteristics using a mixed general linear model in which treatment center was entered as a random effect using SAS GLIMMIX.40

Case mix–adjusted SMRs, the ratio of observed numbers of deaths by predicted numbers of deaths, were computed using patient-specific predicted mortality risk from logistic regression models that did not control for clustering. These analyses were performed using SAS 9.1.

We assessed the geographic clustering of low levels of pre-ESRD nephrology care within the contiguous region defined by ESRD Networks 5, 6, 8, and 13. We examined the clustering of treatment centers in the lowest quintile of pre-ESRD nephrology care via two methods: (1) Spatial scan statistics,41 which identify the most unusual circular clusters of centers with low rates, and (2) spatial relative risk surfaces, which identify more specific areas of statistically significant increases or decreases in the local prevalence of low-rate centers.42

Briefly, spatial scan statistics identify the most unusual collection of cases defined by a local likelihood ratio test statistic comparing the number of cases observed with the number expected (under a hypothesis of constant risk) within circles centered at each CASE LOCATION having radii ranging from the minimum distance between observations up to containing one half of the study population. The approach identifies the collection of cases least consistent with the null hypothesis and evaluates statistical significance via Monte Carlo assignment of case and control status among observation locations.

Spatial relative risk surfaces are defined as the ratio of the spatial density of cases to that of controls. We used kernel density estimation42 to provide the case and control density estimates. Statistical significance is again defined via Monte Carlo assignment of case and control status among observation locations. Unlike the spatial scan statistic, spatial relative risk surfaces can identify clusters of any shape and easily allow identification of multiple “hot” or “cold” spots in the surface.

DISCLOSURES

The analyses on which this publication is based were performed under contract 500-96-P704, entitled “Operation Utilization and Quality Control Peer Review Organization (PRO) for the State of Georgia,” sponsored by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Department of Health and Human Services. The conclusions and opinions expressed and methods used herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services policy. The authors assume full responsibility for the accuracy and completeness of the ideas presented.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a National Institutes of Health Career Development Award K23 DK65634 (H.W.).

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

See related editorial, “Lessons from Geographic Variations in Predialysis Nephrology Care,” on pages 930–932.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ifudu O, Dawood M, Homel P, Friedman EA: Excess morbidity in patients starting uremia therapy without prior care by a nephrologist. Am J Kidney Dis 28: 841–845, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Obrador GT, Pereira BJ: Early referral to the nephrologist and timely initiation of renal replacement therapy: A paradigm shift in the management of patients with chronic renal failure. Am J Kidney Dis 31: 398–417, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goransson LG, Bergrem H: Consequences of late referral of patients with end-stage renal disease. J Intern Med 250: 154–159, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fink J, Blahut S, Reddy M, Light P: Use of erythropoietin before the initiation of dialysis and its impact on mortality. Am J Kidney Dis 37: 348–355, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Avorn J, Winkelmayer WC, Bohn RL, Levin R, Glynn RJ, Levy E, Owen W Jr: Delayed nephrologist referral and inadequate vascular access in patients with advanced chronic kidney failure. J Clin Epidemiol 55: 711–716, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sesso R, Yoshihiro MM: Time of diagnosis of chronic renal failure and assessment of quality of life in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 12: 2111–2116, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Winkelmayer WC, Mehta J, Chandraker A, Owen WF Jr, Avorn J: Predialysis nephrologist care and access to kidney transplantation in the United States. Am J Transplant 7: 872–879, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martinez-Ramirez HR, Jalomo-Martinez B, Cortes-Sanabria L, Rojas-Campos E, Barragan G, Alfaro G, Cueto-Manzano AM: Renal function preservation in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients with early nephropathy: A comparative prospective cohort study between primary health care doctors and a nephrologist. Am J Kidney Dis 47: 78–87, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones C, Roderick P, Harris S, Rogerson M: Decline in kidney function before and after nephrology referral and the effect on survival in moderate to advanced chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 21: 2133–2143, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Innes A, Rowe PA, Burden RP, Morgan AG: Early deaths on renal replacement therapy: The need for early nephrological referral. Nephrol Dial Transplant 7: 467–471, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stack AG: Impact of timing of nephrology referral and pre-ESRD care on mortality risk among new ESRD patients in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis 41: 310–318, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lorenzo V, Martn M, Rufino M, Hernandez D, Torres A, Ayus JC: Predialysis nephrologic care and a functioning arteriovenous fistula at entry are associated with better survival in incident hemodialysis patients: An observational cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis 43: 999–1007, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilbertson DT, Obrador GT, Pereira BJ, Collins AJ: Does predialysis nephrology care influence patient survival after initiation of dialysis? Kidney Int 67: 1038–1046, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Kidney Foundation: K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: Evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis 39[Suppl 1]: S1–S266, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bolton WK, Renal Physicians Association: Renal Physicians Association clinical practice guideline: Appropriate patient preparation for renal replacement therapy—Guideline number 3. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 1406–1410, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Kidney Foundation: NKF-K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for vascular access: Update 2000. Am J Kidney Dis 37[Suppl 1]: S137–S181, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.US Renal Data System: USRDS 2004 Annual Data Report: Atlas of End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States, Bethesda, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2004

- 18.McClellan WM, Soucie JM, Flanders WD: Mortality in end-stage renal disease is associated with facility-to-facility differences in adequacy of hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 1940–1947, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirth RA, Tedeschi PJ, Wheeler JR: Extent and sources of geographic variation in Medicare end-stage renal disease expenditures. Am J Kidney Dis 38: 824–831, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soucie JM, McClellan WM: Early death in dialysis patients: Risk factors and impact on incidence and mortality rates. J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 2169–2175, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bradbury BD, Fissell RB, Albert JM, Anthony MS, Critchlow CW, Pisoni RL, Port FK, Gillespie BW: Predictors of early mortality among incident US hemodialysis patients in the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2: 89–99, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wauters JP, Lameire N, Davison A, Ritz E: Why patients with progressing kidney disease are referred late to the nephrologist: On causes and proposals for improvement. Nephrol Dial Transplant 20: 490–496, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Orlando LA, Owen WF, Matchar DB: Relationship between nephrologist care and progression of chronic kidney disease. N C Med J 68: 9–16, 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Winkelmayer WC, Glynn RJ, Levin R, Owen WF Jr, Avorn J: Determinants of delayed nephrologist referral in patients with chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis 38: 1178–1184, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arora P, Obrador GT, Ruthazer R, Kausz AT, Meyer KB, Jenuleson CS, Pereira BJ: Prevalence, predictors, and consequences of late nephrology referral at a tertiary care center. J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 1281–1286, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coresh J, Byrd-Holt D, Astor BC, Briggs JP, Eggers PW, Lacher DA, Hostetter TH: Chronic kidney disease awareness, prevalence, and trends among U.S. adults, 1999 to 2000. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 180–188, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fox CH, Brooks A, Zayas LE, McClellan W, Murray B: Primary care physicians’ knowledge and practice patterns in the treatment of chronic kidney disease: An Upstate New York Practice-base Research Network (UNYNET) study. J Am Board Fam Med 19: 54–61, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boulware LE, Troll MU, Jaar BG, Myers DI, Powe NR: Identification and referral of patients with progressive CKD: a national study. Am J Kidney Dis 48: 192–204, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McWilliams JM, Zaslavsky AM, Meara E, Ayanian JZ: Impact of Medicare coverage on basic clinical services for previously uninsured adults. JAMA 290: 757–764, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Asch SM, Kerr EA, Keesey J, Adams JL, Setodji CM, Malik S, McGlynn EA: Who is at greatest risk for receiving poor-quality health care? N Engl J Med 354: 1147–1156, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kinchen KS, Sadler J, Fink N, Brookmeyer R, Klag MJ, Levey AS, Powe NR: The timing of specialist evaluation in chronic kidney disease and mortality. Ann Intern Med 137: 479–486, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Obialo CI, Ofili EO, Quarshie A, Martin PC: Ultralate referral and presentation for renal replacement therapy: Socioeconomic implications. Am J Kidney Dis 46: 881–886, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lea JP, McClellan WM, Melcher C, Gladstone E, Hostetter T: CKD risk factors reported by primary care physicians: Do guidelines make a difference? Am J Kidney Dis 47: 72–77, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fisher ES, Wennberg JE: Health care quality, geographic variations, and the challenge of supply-sensitive care. Perspect Biol Med 46: 69–79, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wennberg JA: Practice variations and health care reform: Connecting the dots. Health Aff (Millwood) Suppl Web Exclusives: VAR140–4, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.McClellan WM, Krisher JO: Collecting and using patient and treatment center data to improve care: Adequacy of hemodialysis and end-stage renal disease surveillance. Kidney Int 57[Suppl 74]: S7–S13, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sehgal AR, Leon JB, Siminoff LA, Singer ME, Bunosky LM, Cebul RD: Improving the quality of hemodialysis treatment: A community-based randomized controlled trial to overcome patient-specific barriers. JAMA 287: 1961–1967, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wolfe Wolfe RA, Hulbert-Shearon TE, Ashby VB, Mahadevan S, Port FK: Improvements in dialysis patient mortality are associated with improvements in urea reduction ratio and hematocrit, 1999 to 2002. Am J Kidney Dis 45: 127–135, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kleinbaum DG, Klein M, Pryor ER: Logistic Regression: A Self-Learning Text, 2nd Ed., Springer-Verlag, New York; 2002

- 40.Zhang D: Generalized linear mixed models with varying coefficients for longitudinal data. Biometrics 60: 8–15, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kulldorff M: A spatial scan statistic. Communications in Statistics: Theory and Methods 26: 1487–1496, 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kelsall JE, Diggle PJ: Non-parametric estimation of spatial variation in relative risk. Stat Med 14: 2335–2342, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]