Abstract

We describe a microfluidic immunoassay device that permits sensitive and quantitative multiplexed protein measurements on nanoliter-scale samples. The device exploits the combined power of integrated microfluidics and optically encoded microspheres to create an array of approximately 100 μm2 sensors functionalized with capture antibodies directed against distinct targets. This strategy overcomes the need for performing biochemical coupling of affinity reagents to the device substrate, permits multiple proteins to be detected in a nanoliter-scale sample, is scalable to large numbers of samples, and has the required sensitivity to measure the abundance of proteins derived from single mammalian cells. The sensitivity of the device is sufficient to detect 1000 copies of TNF in a volume of 4.7 nL.

Keywords: microfluidics, immunoassay

Introduction

Immunoassays are one of the most commonly used biochemical techniques for measuring protein abundance in both research and clinical settings. The high selectivity of antibody capture reagents allows for direct and quantitative measurements of protein abundance from complex samples including serum. The fundamental limit to the achievable sensitivity of immunoassays is determined by the binding affinity of the capture reagents and is typically in the nM range [1]. Conventional 96-well microtiter-plate format assay volumes are in the 10–100 μL range and have sensitivities approaching ~10 pg/mL. For a typical cytokine (e.g. TNF, MW ~26 kD) secreted at a copy number of ~105 per cell, this corresponds to a detection sensitivity of 2×107 molecules, requiring a culture of ~200 cells. Detecting the cytokine output from a single cell requires an increase in sensitivity of two orders of magnitude.

Microfluidic systems that allow for the facile manipulation of cells and reagents in nanoliter volumes have enormous potential for enabling measurements of proteins secreted from isolated single cells. The 4–5 orders of magnitude reduction in sample volume (from 10–100 μL to nL volumes) should cause a commensurate reciprocal increase in analyte concentration, such that protein expression by single cells should be easily detectable.

Single cell analysis is becoming more critical as investigators in a wide variety of fields are becoming increasingly aware and concerned about cellular heterogeneity. Two examples from immunology are illustrative. First, intercellular communication between rare leukocytes is critical for a complete understanding of autoimmunity. Second, molecular fingerprints of individual responding immune cells are critical in defining correlates of protective immunity during vaccination. In both cases a comprehensive analysis of single cells is necessary. While flow cytometry has been useful in identifying and measuring cell surface markers, no scalable methodology exists that can analyze multiple analytes secreted by individual live cells. Beyond single cell applications, miniaturization and parallelization of immunoassays within a microfluidic format offers obvious advantages in the consumption of reagents, automation, and reproducibility.

The recent development of fabrication techniques using polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), especially the dense integration of active microvalves [2], has solved many of the miniaturization and automation challenges of microfluidic immunoassays. Although PDMS provides excellent mechanical and optical properties, it presents challenges to implementing robust surface functionalization for the attachment of biomolecules. One obstacle to achieving the full potential of PDMS immunoassay devices is the need for the development of stable and robust capture reagents that are compatible with the fabrication processes. While there have been numerous surface chemistries developed for PDMS, the majority of these require an activation step (typically exposure to oxygen plasma) that is both difficult to control and degrades over time, making subsequent attachment of antibodies irreproducible and inefficient. In addition, previous work has shown that the surface of a sample of cured PDMS is chemically labile resulting in the effective loss of surface bound molecules [3; 4].

Challenges in surface functionalization of microfluidic devices are further aggravated in cases where multiplexed protein detection is desired due to the requirement that multiple distinct capture antibodies be spatially separated on the solid support over as small an area as possible to minimize sample volume. Most microfluidic immunoassay devices demonstrated to date use the fluidic network itself to distribute and isolate different species of capture antibodies using independent channels or microvalves [5; 6; 7; 8]. The antibodies are then coupled to the surface of the channels either covalently or by passive adsorption [5]. In addition to requiring plumbing dedicated exclusively to functionalization, the size of the surface functionalized, and therefore the area over which a single protein species is subsequently captured, is constrained by the dimensions of the microfluidic channel. Pin-spotting [9; 10], piezo-jet [11], and laser-jet[12] print technologies can generate spots with diameters comparable to the typical size of a microfluidic channel (50–100 μm) but require that the microfluidic device subsequently be aligned and bonded to the spotted substrate, typically using baking steps at elevated temperatures that are likely to denature spotted proteins. Devices in which the capture antibodies are patterned at the time of fabrication cannot be reconfigured to measure alternate analytes. This limitation is often inconvenient in a research setting.

Microparticle solution for microfluidic immunoassays

Recently, numerous types of functionalizable, optically distinguishable microparticles have been developed to facilitate high-throughput biochemical assays [13; 14]. The possibility of combining this technology with microfluidic sample handling was recently reviewed by Derveaux et al [15]. We have developed a multiplexed protein detection strategy using pre-functionalized microparticles that offers an easy and flexible approach to multiplex detection and eliminates the difficulties in directly functionalizing PDMS microfluidic devices. The critical element in our approach is the use of a set of optically distinguishable microparticles, each of which is functionalized with an antibody against a protein of interest. Because these particles are significantly smaller (5.6 μm diameter) than the typical size of a microfluidic channel (100 μm), a collection of different beads, each bearing a unique capture antibody, can be flowed into a channel, trapped within an isolated chamber at high density, and then incubated with the sample. The particles do not need to be precisely positioned within the chamber since their identity (and hence the identity of the captured target material) is determined by imaging after the assay is complete.

This approach offers several advantages over microfluidic immunoassay devices that have been demonstrated to date. The number of measurements possible on a nanoliter sized sample (106 cubic microns) is dramatically increased because tens or even hundreds of different particles could be loaded into a single chamber, each with an affinity-capture reagent against a different target molecule. In this format, the multiplexing capacity is limited by the availability of capture reagents. The approach is flexible and efficient as the collection of microparticles loaded (and hence targets assayed) can be varied by each user depending on the particular application and only requires the use of those capture antibodies which are essential to the experiment. The attachment of the antibodies to the beads is performed in bulk before the beads are loaded into the device, avoiding the need to perform surface chemistry on PDMS or the need to design additional plumbing to handle construction of the array. Because the fluorescently labeled analyte is concentrated on the surface of the bead (~100 μm2) rather than being spread over the entire surface of the fluidic chamber (~104 μm2), detection sensitivity, which is generally limited by autofluorescent background, is significantly increased. The sample volume is precisely defined by the closed geometry of the microfluidic channels in contrast to “flow-through” designs which perfuse the sample continuously over the detection volume to increase sensitivity and therefore require precise control of the sample flow-rate to ensure accurate quantification.

Experimental Section

Device Design

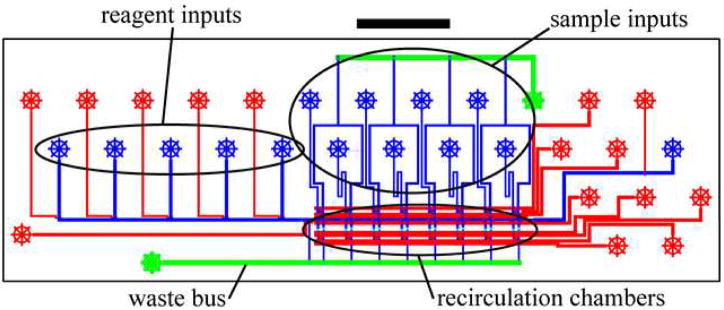

The chip design is shown in Figure 1. The device incorporates eight independent sample chambers (4.7 nL volume each) which are loaded and operated in parallel. Uniform loading and washing is accomplished by delivering all samples through equal length input lines and by delivering wash solution through a high-volume (65 μm × 200 μm) “fluidic bus”. Each sample chamber consists of a recirculating ring (13 μm channel height) divided by two sets of three “trap channels” (2.5 μm channel height) that prevent the passage of 5.6 μm diameter capture microspheres while allowing passage of fluid (Figure 1B). The width of the trap channels was reduced to 30 μm in order to maintain an approximately 12:1 (width:height) aspect ratio and prevent collapse during fabrication. Three trap channels are placed in parallel in order to achieve sufficient fluid flow through the recirculating ring. Capture microspheres, as well as reagents for the sandwich immunoassay are delivered through a common input line to all of the sample chambers.

Figure 1. Chip design.

A) Overview of immunoassay chip. Control channels are shown in red (23 μm height); flow channels are shown in blue (13 μm height) or green (65 μm height). The scale bar shown is 5 mm. B) Detail of one recirculating sample chamber. Control channels are shown in red (100 μm width); flow channels are show in blue (13 μm height) or light blue (2.5 μm height). The three valves forming the recirculating peristaltic pump are labeled p1, p2, and p3. The total volume of the recirculating chamber is 4.7 nL. Sample is loaded into a 2.7 nL segment of this chamber.

Three valves (labeled p1, p2, and p3 in Figure 1B.) permit pumping of the sample and the immunoassay reagents over the beads, significantly improving capture efficiency through enhanced sample interaction with the sensing elements and greatly reducing the assay time over that which would be possible by diffusive mixing alone. We found that blockages due to inadvertent trapping of beads in partially constricted channels could be eliminated by avoiding control-layer “cross-overs” of channels in the fluidic network that carry capture microspheres.

Device Fabrication

The PDMS microfluidic device was fabricated using multi-layer soft-lithography [2; 16]. Complete fabrication details are given in the Supplementary Information.

Device Control

Pressure to the pneumatic control lines was switched between 0 and 24 psi by microsolenoid valves (Fluidigm) that were driven by a custom 32-channel breakout box and via a DIO-32HS board (National Instruments) with software written in LabVIEW (National Instruments).

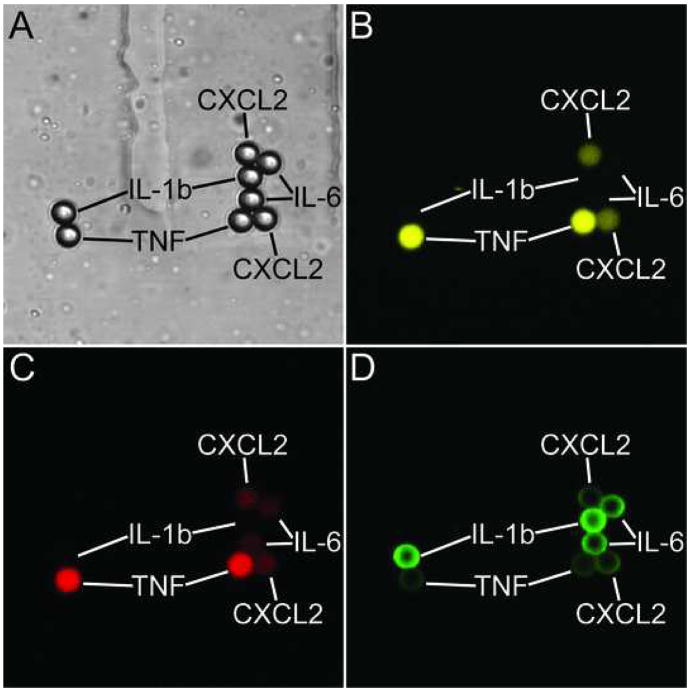

Device Operation

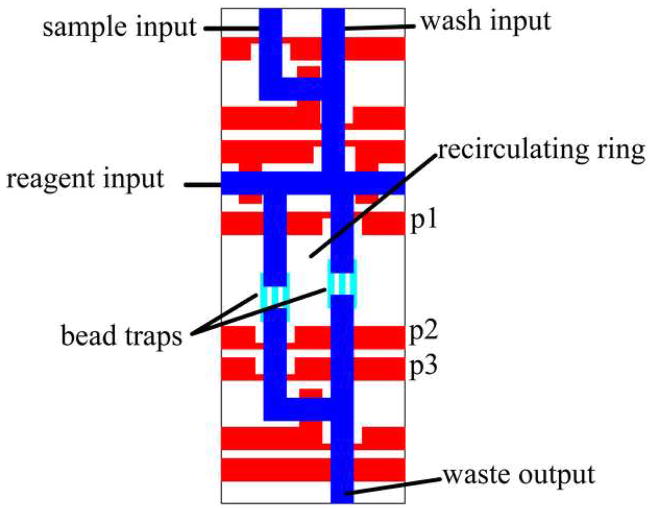

Fluorinert FC-40 (Sigma) was used to fill the control lines. All of the active regions were incubated with blocking solution (see Reagents below) and subsequently washed before detection microspheres and sample were loaded into the chip. Two detection microspheres for each of four analytes (TNF, CXCL2, IL-6, and IL-1b) were then individually loaded into the recirculating sample chambers, positioned against the traps by peristaltic pumping, and the number in each chamber verified by inspection. We found that diluting the microspheres to approximately 0.01 nL−1 significantly reduced the presence of clumps and allowed for precise control of the loading process. A precise volume of sample, defined by the geometry of the fluidic network (2.7 nL), was then loaded into half of the recirculation chamber on the side opposite to the trapped beads. The sample loading time was short enough (approximately one second) that diffusion of protein analytes beyond the loading volume was insignificant. An active valve located behind the microsphere trapping region prevented backflow and loss of beads into the common input line as the PDMS channels expanded and contracted with fluid pressure changes during operation. The recirculating ring was pressurized to 5 psi and the peristaltic pumps activated to pass the sample over the detection beads for 2 hours. Pressurization of the recirculating ring increases the achievable pumping speed by increasing the restoring force on each of the valves used as elements of the peristaltic pump. Using 1 μm diameter microsheres as tracers, the flow rate around the recirculating ring was measured to be approximately 1.5 nL/s. The recirculating chamber was then washed, the pooled biotinylated secondary-antibody mixture introduced into the common input line, and the pump activated again for 1 hour. The recirculating chamber was then washed again, the streptavidin-Alexa-488 labeling reagent introduced into the common input line, and the pump activated for 30 minutes. Finally, both sides of the ring were washed, and each detection chamber imaged by confocal microscopy to identify each detection bead and quantify the amount of each protein present in the sample. A schematic of the assay procedure is depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Device operation.

A) Detection microspheres (5.6 μm diameter) localized in a 13 μm high channel (dark blue overlay) by 2.5 μm high trap channels (light blue overlay). Illustration of various fluid handling steps for performing an immunoassay. Closed valves are indicated with a (×) while valves operating as elements of a peristaltic pump are indicated with a (●). Microspheres and labeling reagents (green) are loaded into the top of the recirculating ring (B) and distributed by peristaltic pumping (C). Wash solution (pink) is introduced independently into each side of the ring (D,E), exchanging the volume approximately 10 times during each wash cycle. Sample is introduced into the right side of the recirculating ring (F) and flowed over the detection microspheres by peristaltic pumping (G).

Reagents

Purified recombinant murine protein standards were purchased from R&D Systems and combined at the following concentrations: TNF, 4.9 ng/mL; CXCL2, 7.0 ng/mL; IL-6, 15 ng/mL; IL-1b, 35 ng/mL. This mixture was diluted with 1% BSA in PBS (pH 7.3) (Diluent Solution) to create the test samples. The active parts of the chip were blocked with a solution of 1% BSA (Pierce) and 5% FBS (Hyclone) in PBS (Blocking Solution) to minimize non-specific binding of both protein analytes and microspheres. The active parts of the device were washed between each step with 0.05% Tween 20 (Acros) in PBS (Wash Solution). Microspheres functionalized with capture antibodies against murine TNF, CXCL2, IL-6, and IL-1b were purchased as individual kits (R&D Systems) and diluted 1:10 (v/v) with 0.1% BSA in PBS before being loaded into the chip. The TNF, IL-6, and IL-1b antibodies were monoclonal while the CXCL2 antibody was polyclonal. The biotinylated secondary antibodies from each kit were combined in Diluent Solution to a final dilution of 1:10 (v/v). Streptavidin conjugated to Alexa-488 (Invitrogen) was diluted 1:10 (v/v) in Diluent Solution, and used to label the biotinylated secondary antibodies. All reagents, except the microspheres, were passed through a 0.22 μm filter before being introduced into the device.

Imaging

Each chamber on the chip was imaged on a Leica TCS-SP2 confocal microscope to determine the identity of each capture bead and quantify the amount of captured protein. Images were acquired using a 40× NA = 0.55 objective with the diameter of the output confocal pinhole adjusted to 600 μm. With these settings, the full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) of the point-spread-function on the z-direction was ~10 μm, ensuring that quantification of fluorescence emission from the 5.6 μm detection beads was relatively insensitive to focus position. The emission intensity in each channel was digitized at 8-bit resolution. The embedded “coding fluorophores” in each bead were excited at 633 nm using a He-Ne laser and the emission intensity in two passbands (649–679 nm and 711–741 nm) was used to identify each of the four beads types and thereby the capture antibody coupled to each of their surfaces. Simultaneously, in order to quantify the amount of protein captured, the beads were illuminated at 488nm using an Argon-ion laser to excite the Alexa-488 fluorophore conjugated to the streptavidin detection reagent, and the emission was measured in a third passband (500–560nm).

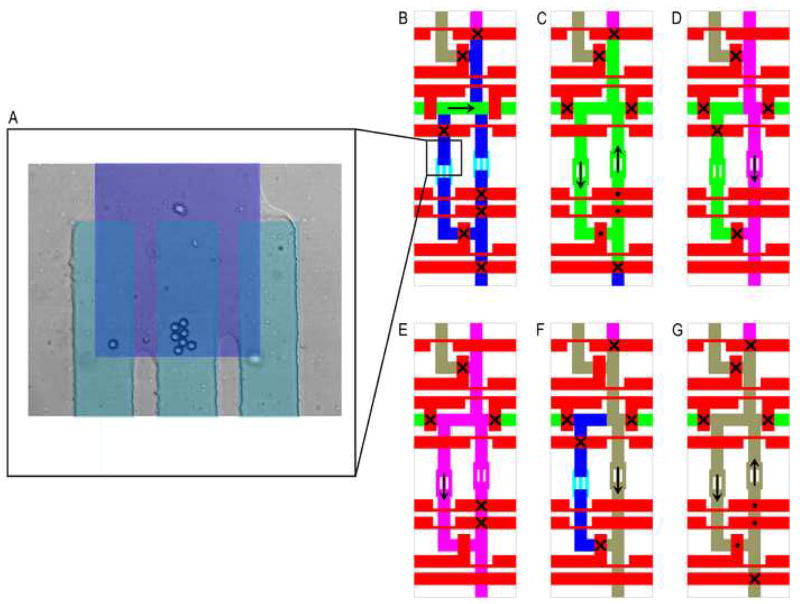

Image Analysis

Images of each detection chamber were quantified using ImageJ (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/). The background level in each image was determined by averaging the mean pixel intensities in five 5.5 μm circular aperture (1162 pixels total area) selected manually to be free of any objects. The fluorescent intensity of each bead in each channel was determined by measuring the total intensity in a 5.5 μm circular aperture and subtracting the background level of the image. The aperture size was chosen to be slightly smaller than the diameter of the beads in order to minimize cross-talk between beads that were touching. Image analysis was straightforward as the beads were confined by the channels to a single plane and do not overlap (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Detection microspheres after completion of sandwich immunoassay.

A) Transmitted light image showing detection beads and trapping channels. False-color fluorescent images: B) “coding channel 1” (633 nm excitation, 649–679 nm emission) C) “coding channel 2” 633 nm excitation, (711–741 nm emission); D) “detection channel” (488 nm excitation, 500–560 nm emission). Emission in the 649–679 nm and 711–741 nm passbands (which arises from fluorophores impregnated into the plastic microspheres) was used to identify the species of capture antibody attached to the surface of each bead, and thereby the species of captured protein. Emission in the 500–560 nm passband (Steptavidin-Alexa-488 labeling reagent) is used to quantify the amount of target protein on the surface of each bead.

Results and Discussion

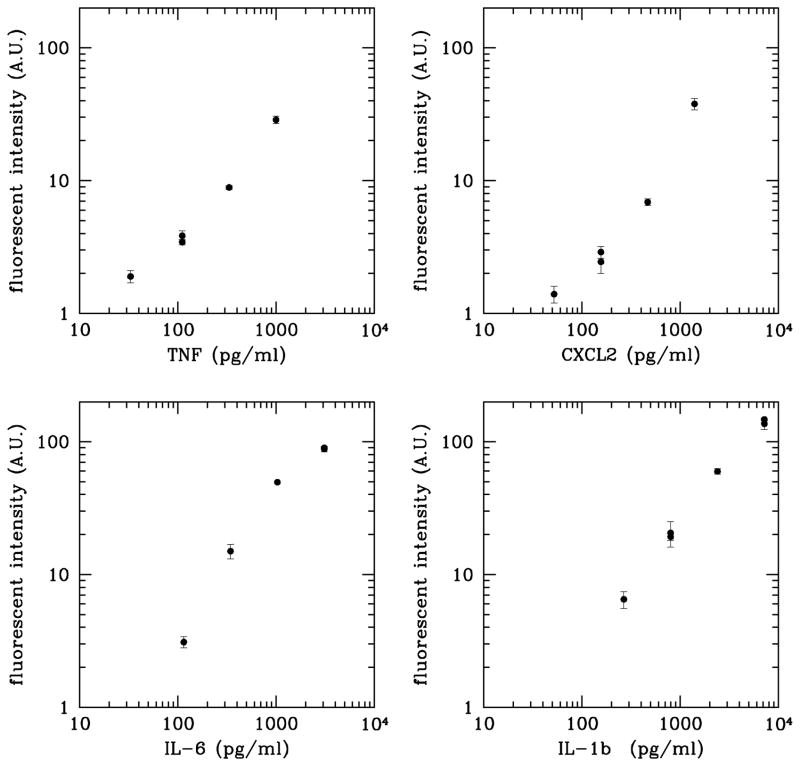

We tested the sensitivity and reproducibility of the device using a mixture of four recombinant murine protein standards (TNF, CXCL2, IL-6, and IL-1b). Two of the concentrations were assayed in duplicate using independent chambers on the chip. The range of concentrations (~pg to ~ng/ml) was chosen to match those expected to be secreted by murine bone-marrow-derived macrophages maintained in culture at a typical cell density. All four proteins were detected down to concentrations approaching ~100 pg/ml and TNF was detected at 33 pg/ml (0.6 pM) in the 2.7 nL sample volume (Figure 4). This corresponds to detecting the presence of ~1000 molecules (~2 zeptomoles) of TNF in the recirculating chamber, although we cannot directly measure the actual number of molecules bound to the surface of the beads. CXCL2 was detected at similar levels. A negative control, consisting of diluent solution with none of the recombinant proteins present yielded no measurable signal on any species of detection microsphere.

Figure 4. Detection of four proteins in a 4.7 nL chamber.

A mixture of TNF, CXCL2, IL-6, and IL-1b was serially diluted, introduced into the device, and processed as described in the text. Error bars indicate the spread in intensity between two identical beads in the same chamber. Duplicate points for the same protein plotted at the same concentration represent measurements taken in distinct chambers.

In this device, the ultimate sensitivity is limited by fluorescence of the plastic itself as well as from the red “coding fluorophores” impregnated within each microsphere. The set of commercially available microspheres (Luminex100 system) used in our device consists of 100 different mixtures of two labeling dyes. Each code differs in brightness by a factor of two from the nearest code. These intensity differences are more than sufficient to uniquely identify the code on each bead by imaging. The sensitivity of detection would be enhanced by using beads with the lowest intensity codes in order to minimize cross-talk from the coding fluorophores into the detection channel.

The small numbers of target molecules typically present in nanoliter-scale samples place stringent requirements on detection sensitivity. The optical path-length through the samples (10–100 microns) are generally too short to make absorptive dyes effective and therefore most devices demonstrated to date have used fluorescent detection. Detection of small numbers of surface-bound fluorescent molecules is typically limited by the autofluorescence of the substrate itself. It is therefore advantageous to localize the capture antibodies over as small an area as possible. In addition, the large surface-area to volume ratio in microfluidic channels compared to microtiter plates requires stringent control of non-specific binding both to reduce background and to limit sample loss. The rate of analyte capture by surface-bound antibodies can be very slow as flow in microfluidic devices is almost always laminar and mixing occurs only by diffusion.

Conclusion

Several other groups have used functionalized microparticles to perform immunoassays in micrfluidic devices. Murakami et al described a device with sufficient sensitivity to detect a single analyte, FK506, at 10 pg/mL in 5 μL, corresponding to ~50fg.[17] Klostranec et al employed quantum dot labeled microparticles to perform multiplexed protein detection of pM concentrations using relatively large (100 μL) sample volumes [18]. Using a single channel and a membrane filter etched into a silicon substrate to trap functionalized microspheres, Liu et al achieved a sensitivity of 22 ng/mL for SGIV virus particles in a 100 μL) sample [19]. We have demonstrated a microfluidic device that can simultaneously measure multiple proteins at pg/mL concentrations in nanoliter rather than microliter volumes. This corresponds to an absolute sensitivity of ~0.09 fg (~2 zeptomoles) of TNF. To our knowledge, this exceeds by several orders of magnitude the sensitivity of any previously published bead-based microfluidic immunoassay device. The ability to achieve this sensitivity in such small volumes will be critical for applications that require detection of the protein content of individual cells.

By using optically identifiable microparticles, functionalized off-chip with affinity reagents, we have eliminated the need to perform chemical coupling to PDMS in the device, thereby decoupling the device fabrication process from the surface chemistry required to functionalize the detection elements. Although the present design uses antibody-coupled polystyrene microspheres that are labeled with embedded fluorophores, the concept can be applied to any type of microparticles which are optically distinguishable and can be localized by mechanical, electrical, or magnetic forces applied within a fluidic network. Our device architecture is ultimately scalable to several hundred chambers per square centimeter that can be operated in a highly parallel fashion, making it well-suited for automated protein quantification of multiple samples. Achieving very high levels of integration will require further development of methods for distributing functionalized particles to each detection volume. Optical tweezers, hydrodynamic trapping or addressable microfluidic arrays with upstream sorting fluidics [20] may provide a solution to this challenge, although integrated microfluidic particle handling on this scale has not been demonstrated. The method presented here has the sensitivity to measure proteins at absolute copy numbers that are typically expressed or secreted from single cells. When integrated with additional fluidics for single cell handling we anticipate that this technology will find broad applicability.

Supplemental Materials

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Caltech Microfluidics Foundry for access to the equipment required for device fabrication. The authors also thank Stephen Quake for thoughtful comments and suggestions on the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH AI063007, NIH R01 AI25032, NIH R01 AI32972, NIH P50 GM076547, NIH U54 CA119347.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information Available

Additional information as noted in text. This material is available online.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Wark KL, Hudson PJ. Latest technologies for the enhancement of antibody affinity. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2006;58:657–70. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2006.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Unger MA, Chou HP, Thorsen T, Scherer A, Quake SR. Monolithic microfabricated valves and pumps by multilayer soft lithography. Science. 2000;288:113–6. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5463.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ren X, Bachman M, Sims C, Li GP, Allbritton N. Electroosmotic properties of microfluidic channels composed of poly(dimethylsiloxane) J Chromatogr B Biomed Sci Appl. 2001;762:117–25. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(01)00327-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang B, Abdulali-Kanji Z, Dodwell E, Horton JH, Oleschuk RD. Surface characterization using chemical force microscopy and the flow performance of modified polydimethylsiloxane for microfluidic device applications. Electrophoresis. 2003;24:1442–50. doi: 10.1002/elps.200390186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bange A, Halsall HB, Heineman WR. Microfluidic immunosensor systems. Biosens Bioelectron. 2005;20:2488–503. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2004.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kartalov EP, Zhong JF, Scherer A, Quake SR, Taylor CR, Anderson WF. High-throughput multi-antigen microfluidic fluorescence immunoassays. Biotechniques. 2006;40:85–90. doi: 10.2144/000112071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dodge A, Fluri K, Verpoorte E, de Rooij NF. Electrokinetically driven microfluidic chips with surface-modified chambers for heterogeneous immunoassays. Anal Chem. 2001;73:3400–9. doi: 10.1021/ac0015366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yakovleva J, Davidsson R, Lobanova A, Bengtsson M, Eremin S, Laurell T, Emneus J. Microfluidic enzyme immunoassay using silicon microchip with immobilized antibodies and chemiluminescence detection. Anal Chem. 2002;74:2994–3004. doi: 10.1021/ac015645b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reese MO, van Dam RM, Scherer A, Quake SR. Microfabricated fountain pens for high-density DNA arrays. Genome Res. 2003;13:2348–52. doi: 10.1101/gr.623903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Auburn RP, Kreil DP, Meadows LA, Fischer B, Matilla SS, Russell S. Robotic spotting of cDNA and oligonucleotide microarrays. Trends Biotechnol. 2005;23:374–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lausted C, Dahl T, Warren C, King K, Smith K, Johnson M, Saleem R, Aitchison J, Hood L, Lasky SR. POSaM: a fast, flexible, open-source, inkjet oligonucleotide synthesizer and microarrayer. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R58. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-8-r58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barron JA, Young HD, Dlott DD, Darfler MM, Krizman DB, Ringeisen BR. Printing of protein microarrays via a capillary-free fluid jetting mechanism. Proteomics. 2005;5:4138–44. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Braeckmans K, De Smedt SC, Leblans M, Pauwels R, Demeester J. Encoding microcarriers: present and future technologies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2002;1:447–56. doi: 10.1038/nrd817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finkel NH, Lou X, Wang C, He L. Barcoding the microworld. Anal Chem. 2004;76:352A–359A. doi: 10.1021/ac0416463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Derveaux S, Stubbe BG, Braeckmans K, Roelant C, Sato K, Demeester J, De Smedt SC. Synergism between particle-based multiplexing and microfluidics technologies may bring diagnostics closer to the patient. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2008;391:2453–67. doi: 10.1007/s00216-008-2062-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thorsen T, Maerkl SJ, Quake SR. Microfluidic large-scale integration. Science. 2002;298:580–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1076996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murakami Y, Endo T, Yamamura S, Nagatani N, Takamura Y, Tamiya E. On-chip micro-flow polystyrene bead-based immunoassay for quantitative detection of tacrolimus (FK506) Anal Biochem. 2004;334:111–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klostranec JM, Xiang Q, Farcas GA, Lee JA, Rhee A, Lafferty EI, Perrault SD, Kain KC, Chan WC. Convergence of quantum dot barcodes with microfluidics and signal processing for multiplexed high-throughput infectious disease diagnostics. Nano Lett. 2007;7:2812–8. doi: 10.1021/nl071415m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu WT, Zhu L, Qin QW, Zhang Q, Feng H, Ang S. Microfluidic device as a new platform for immunofluorescent detection of viruses. Lab Chip. 2005;5:1327–30. doi: 10.1039/b509086e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fu AY, Chou HP, Spence C, Arnold FH, Quake SR. An integrated microfabricated cell sorter. Anal Chem. 2002;74:2451–7. doi: 10.1021/ac0255330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.