Abstract

Background

Temperature affects essentially every aspect of the biology of poikilothermic animals including the energy and mass budgets, activity, growth, and reproduction. While thermal effects in ecologically important groups such as daphnids have been intensively studied at the ecosystem level and at least partly at the organismic level, much less is known about the molecular mechanisms underlying the acclimation to different temperatures. By using 2D gel electrophoresis and mass spectrometry, the present study identified the major elements of the temperature-induced subset of the proteome from differently acclimated Daphnia pulex.

Results

Specific sets of proteins were found to be differentially expressed in 10°C or 20°C acclimated D. pulex. Most cold-repressed proteins comprised secretory enzymes which are involved in protein digestion (trypsins, chymotrypsins, astacin, carboxypeptidases). The cold-induced sets of proteins included several vitellogenin and actin isoforms (cytoplasmic and muscle-specific), and an AAA+ ATPase. Carbohydrate-modifying enzymes were constitutively expressed or down-regulated in the cold.

Conclusion

Specific sets of cold-repressed and cold-induced proteins in D. pulex can be related to changes in the cellular demand for amino acids or to the compensatory control of physiological processes. The increase of proteolytic enzyme concentration and the decrease of vitellogenin, actin and total protein concentration between 10°C and 20°C acclimated animals reflect the increased amino-acids demand and the reduced protein reserves in the animal's body. Conversely, the increase of actin concentration in cold-acclimated animals may contribute to a compensatory mechanism which ensures the relative constancy of muscular performance. The sheer number of peptidase genes (serine-peptidase-like: > 200, astacin-like: 36, carboxypeptidase-like: 30) in the D. pulex genome suggests large-scaled gene family expansions that might reflect specific adaptations to the lifestyle of a planktonic filter feeder in a highly variable aquatic environment.

Background

Planktonic crustaceans of the genus Daphnia experience pronounced variations in ambient parameters such as oxygen concentration and temperature in the field and show plastic adaptive responses to these environmental changes. Differential regulation of gene expression provides specific sets of proteins for the maintenance of cellular function under altered ambient conditions. The recent release of the Daphnia pulex genome sequence [1,2] offers the opportunity to relate proteomic adjustments to the differentially regulated genes.

Temperature affects the performance of poikilothermic animals at all levels of biological organization ranging from biochemical reactions via physiological processes to organismic properties such as fecundity and reproductive success. Acute changes in water temperature, for example, have a strong effect on systemic parameters such as heart and ventilation rate of Daphnia spp. (e.g. [3]). However, such physiological perturbations can be damped by acclimatory processes. Previous studies [3-6] have shown that the metabolic rates, heart and ventilation rates, and muscular performances of several Daphnia species at 10°C and 20°C are not as different as expected from the Q10 rule, provided the animals have the chance to acclimate to the temperature at which they were tested. Such a type of compensatory control (metabolic cold adaptation) is primarily based on adjustments in enzyme concentration [7]. Nevertheless, a more or less reduced metabolic rate in the cold decreases the nutritive requirements [8] and causes also a retardation in somatic growth and development [9-11]. To mechanistically explain the role of temperature acclimation for the control of physiological processes, it is essential to know the adjustments which occur at the proteomic level.

The present study analyzed the protein expression patterns of 10°C and 20°C acclimated animals of Daphnia pulex under normoxic conditions. Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and mass spectrometry were employed to identify the major elements of the temperature-induced subset of the proteome. Based on their putative functions, the probable physiological role of these sets of proteins are discussed.

Results

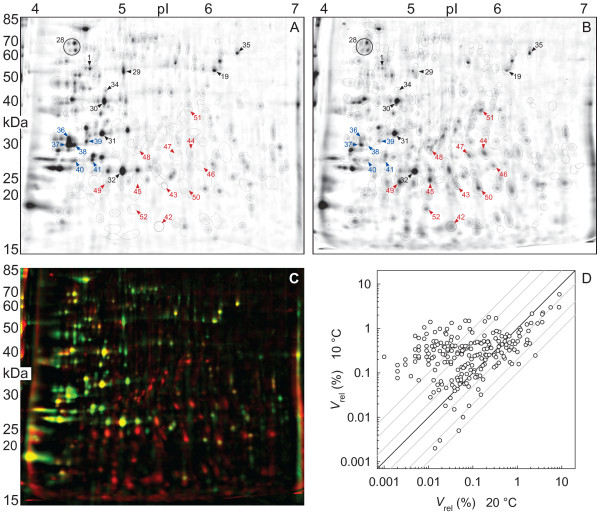

Two-dimensional gels were prepared from total soluble proteins extracted from 10°C or 20°C acclimated cultures of Daphnia pulex kept under normoxia (oxygen partial pressure: 20 kPa). A total of 224 spots were detected in representative fusion images for each acclimation condition (Figure 1A, B; encircled spots). The dual-channel representation of both fusion gels revealed a large set of cold-induced proteins of low molecular weight (Mr < 40 kDa) in the lower right diagonal half of the gel (Figure 1C; red-colored spots). Proteins of reduced expression in the cold were mainly confined to the low-pI range (pI = 4–5) in the upper left diagonal half of the gel (green-colored spots).

Figure 1.

2D protein gels from Daphnia pulex acclimated at 20°C (A) and 10°C (B). Gel images represent fusion (average) images from a set of three (A) or two (B) biological replicates. Consensus spots used for comparison in (D) are encircled. Blue and red numbers indicate cold-repressed and cold-induced protein spots that were picked from the 2D gels for mass-spectrometric analysis. Black numbers indicate previously identified proteins [12]. (C) Dual-channel representation of the gel images shown in (A) and (B). Protein spots of similar expression intensity appear in yellow. Green indicates that spots are much stronger or unique on the gel from 20°C-acclimated animals, whereas red means that spots are much stronger or unique in the gel from 10°C-acclimated D. pulex. (D) Scatter plot showing the comparison of expression levels in the two fusion images (Vrel: relative spot volume).

A total number of 17 spots comprising cold-repressed proteins (36–41, Figure 1A) and cold-induced proteins (spots 42–52, Figure 1B) were successfully identified by mass spectrometry (Tables 1, see Table 2 for corresponding protein IDs and gen models). Additionally included into the inter-gel comparison was a set of spots (1, 19–22, 28–32, 34–35), the identity of which was already known from a previous study [12]. These spots showed either constitutive or temperature-dependent expressions.

Table 1.

Identified proteins from Daphnia pulex acclimated to 10°C or 20°C

| Spot no. | Specificity N10: N20 | Matched peptide sequences | Sequence coveragea) | Mascot scoreb) | Mrgel/Mrpredicted | pI gel/pI predicted | SP Length | PP Length | Putative function (symbolic name) |

| Proteolytic enzymes | |||||||||

| 36 | 0.3* | 1. VVAGEHSLR 2. SVDVPVVDDDTCNR |

8.9% | 149 | 30/26–29 | 4.4/4.4–4.8 | 15 | 27 | Trypsin (TRY5L) |

| 1. LTAAEEPTRVEIR 2. IRNDVALIK |

7.5% | 80 | 30/25–30 | 4.4/4.5–5.3 | 18 | 48 | Chymotrypsin (CHY1A) | ||

| 37 | 0.2* | 1. GVTDLTIFR 2. VVAGEHSLR 3. VVAGEHSLRTDSGLEQNR |

9.8% | 159 | 29/26–29 | 4.4/4.4–4.8 | 15 | 27 | Trypsin (TRY5F) |

| 1. VVAGEHSLR 2. SVDVPVVDDDTCNR |

8.9% | 149 | 29/26–29 | 4.4/4.4–4.8 | 15 | 27 | Trypsin (TRY5L) | ||

| 38 | 0.5* | 1. GLADADIAVFK 2. LIWMGQYNR 3. YYRDELAGK |

10.7% | 123 | 29/30 | 4.5/4.5 | 19 | Endoribonuclease-like protein (ERNA) | |

| 1. GLADADIAVFK 2. LIWMGQYNR 3. YYRDELAGK |

8.0% | 123 | 29/39 | 4.5/4.6 | 20 | Endoribonuclease-like protein (ERNB) | |||

| 1. VVAGEHSLR 2. SVDVPVVDDDTCNR |

8.9% | 149 | 29/26–29 | 4.5/4.4–4.8 | 15 | 27 | Trypsin (TRY5L) | ||

| 1. GVTDLTIFR 2. VVAGEHSLR |

6.5% | 80 | 29/26–29 | 4.5/4.4–4.8 | 15 | 27 | Trypsin (TRY5F) | ||

| 39 | 0.4* | 1. VVAGEHSLR 2. SVDVPVVDDDTCNR |

8.9% | 149 | 29/26–29 | 4.6/4.4–4.8 | 15 | 27 | Trypsin (TRY5L) |

| 1. GVTDLTIFR 2. VVAGEHSLR |

6.5% | 120 | 29/26–29 | 4.6/4.4–4.8 | 15 | 27 | Trypsin (TRY5F) | ||

| 40 | 0.6* | 1. TTEEYYVSVQK 2. TGGGCYSYIGR |

6.5% | 112 | 25/23–27 | 4.5/4.7–4.6 | ? | 39 ? | Astacin (ACN2) |

| 1. GVTDLTIFR 2. VVAGEHSLR |

6.5% | 109 | 25/26–29 | 4.5/4.4–4.8 | 15 | 27 | Trypsin (TRY5F) | ||

| 41 | 0.4* | 1. LTAAEEPTR 2. LTAAEEPTRVEVR 3. IINDVALIK |

9.1% | 141 | 25/25–30 | 4.7/4.4–5.0 | 18 | 47 | Chymotrypsin (CHY1C) |

| 28 | 1.2 | see [12] | Peptidase M13 Peptidase M2 Carboxylesterase, type B Sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase Sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase |

||||||

| 31 | 0.6 | see [12] | 30/34–45 30/35–46 29/26–29 |

4.8/4.9–4.8 4.8/5.1–4.9 4.4/4.4–4.8 |

16 16 15 |

92 93 27 |

Carboxypeptidase A (CPA1A) Carboxypeptidase A (CPA1B) Trypsin (TRY5F) |

||

| 32 | 0.3 | see [12] | 23/24–27 | 5.0/5.2–5.4 | 17 | 24 | Trypsin (TRY4B) | ||

| Egg yolk proteins & precursors | |||||||||

| 43 | 7.3* | see Figure 2 | /190–220 | /6.4–6.7 | 17–20 | Vitellogenin (VTG1, VTG2, VTG4) | |||

| 44 | 7.1* | see Figure 3 see Figure 2 |

15.7% 2.8% |

271 | 25/42 25/220 |

5.8/5.3 5.8/6.7 |

17 17 |

Actin Vitellogenin (VTG1) |

|

| 45 | 5.9* | see Figure 2 | 2.2% | 132 | 21/190 | 5.2/6.4 | 20 | Vitellogenin (VTG4) | |

| 46 | 5.2* | see Figure 2 | 2.9% | 361 | 21/220 | 5.9/6.7 | 17 | Vitellogenin (VTG1) | |

| 47 | 4.9* | see Figure 3 see Figure 2 |

9.6% 2.0% |

25/42 25/220 |

5.6/5.3 5.6/6.7 |

17 | Actin Vitellogenin (VTG1, VTG2) |

||

| 1. EDQMDYLEEK 2. LLVEKER 3. YSVDEELNK |

3.6% | 25/83 | 5.6/4.7 | HSP90 | |||||

| 49 | 4.4* | see Figure 2 | ?.?% | ??? | 21/190–220 | 4.8/6.4–6.7 | 17–20 | Vitellogenin (VTG1, VTG2, VTG4) | |

| 50 | 4.2* | see Figure 2 | 2.2% | 163 | 20/220 | 5.7/6.7 | 17 | Vitellogenin (VTG1) | |

| 52 | 3.7 | see Figure 2 | 3.0% | 344 | 18/220 | 5.1/6.7 | 17 | Vitellogenin (VTG1, VTG2) | |

| Cytoskeleton & muscle proteins | |||||||||

| 48 | 4.5* | see Figure 2 see Figure 3 |

?.?% | ??? | 27/42 | 5.2/5.3 | Actin Vitellogenin (VTG4) |

||

| 1. EQLDEESEAK 2. AEELEDAKR 3. ATVLANQMEK |

27/220 | 5.2/5.9 | Myosin heavy chain (MHC-1) | ||||||

| 1. LTTDPAFLEK 2. NAAAVHEIR 3. GDLGIEIPPEK |

27/?? | 5.2/? | Pyruvate kinase | ||||||

| 51 | 3.6* | see Figure 3 | ?.?% | ??? | 36/42 | 5.7/5.3 | Actin | ||

| ATPase | |||||||||

| 42 | 9.8* | 2. GNEDLSTAILK 3. MDELQLFK 4. GDIFIVR 5. KQLALIK 6. EMVELPLR |

5.1% | 214 | 16/89 | 5.3/5.0 | AAA+ ATPase | ||

| Carbohydrate-modifying enzymes | |||||||||

| 35 | 1.2 | see [12] | α-Amylase (AMY) | ||||||

| 34 | 1.0 | see [12] | Exo-β-1,3-Glucanase (EXG5) | ||||||

| 1 | 0.4 | see [12] | Cellubiohydrolase (CEL7A) | ||||||

| 29 | 0.3 | see [12] | Endo-β-1,4-Glucanase (CEL9A) Paramyosin (PMY) |

||||||

| 30 | 0.6 | see [12] | Endo-β-1,4-Mannanase (MAN5A) β-1,3-Glucan-binding protein |

||||||

| 19 | 0.6 | see [12] | Enolase (ENO) | ||||||

Identification was based on 2D gel electrophoresis and nano-HPLC-ESI-MS/MS analysis of trypsin-digested proteins matched against the "Frozen Gene Catalog" of the D. pulex protein database [2]. The compiled information includes the spot number (Figure 1A, B), the 10-to-20°C expression ratio, the number and sequences of matched peptides, the sequence coverage, the Mascot score as a statistical measure of identification probability, the experimental and theoretical molecular weight (Mr) and isolectric point (pI) of the mature protein (without signal peptide), the predicted length of the N-terminal signal peptide (SP) in secretory proteins, as well as the putative function and symbolic name of the protein. The length of the putative pro-peptide (PP) is additionally provided for proteolytic enzymes that are secrected as inactive precursors (zymogens). The predicted Mr and pI values of zymogens and the mature enzymes are given as value ranges. The amino acid sequences of the identified proteins were derived from the gene models listed in Table 2. a)percentage of predicted protein sequence covered by matched peptides. b)Probability-based MOWSE score: -10*Log(P), where P is the probability that the observed match is a random event. Scores >38 indicate identity or extensive homology (p < 0.05). Protein scores are derived from ions scores as a non-probabilistic basis for ranking protein hits. The Mascot-score calculation was performed using whole-protein sequence (including the N-terminal signal peptide in case of extracellular proteins). *p < 0.05 (t-Test).

Table 2.

List of referred proteins and gene models

| Putative function | Symbol | Model name | Protein ID | Reference ID |

| Trypsin | TRY1 | PIR_PASA_GEN_1500076 | 347826 | 301879 |

| Trypsin | TRY2 | PIR_PASA_GEN_5300037 | 347779 | 306771 |

| Trypsin | TRY3 | PIR_PASA_GEN_6100026 | 347764 | 307264 |

| Trypsin | TRY4A | PIR_fgenesh1_pg.C_scaffold_23000179 | 347804 | 102943 |

| Trypsin | TRY4B | PIR_estExt_fgenesh1_kg.C_230008 | 347242 | 230885 |

| Trypsin | TRY5A | PIR_PASA_GEN_4200081 | 347777 | 305924 |

| Trypsin | TRY5B | PIR_NCBI_GNO_4200123 | 347775 | 321745 |

| Trypsin | TRY5C | PIR_NCBI_GNO_4200124 | 347774 | 106429 |

| Trypsin | TRY5D | PIR_estExt_fgenesh1_kg.C_420021 | 347772 | 231151 |

| Trypsin | TRY5E | PIR_NCBI_GNO_4200126 | 347773 | 321748 |

| Trypsin | TRY5F | PIR_SNAP_00016212 | 347771 | 231152 |

| Trypsin | TRY5G | PIR_NCBI_GNO_4200130 | 347770 | 248155 |

| Trypsin | TRY5H | PIR_PASA_GEN_4200082 | 347769 | 305925 |

| Trypsin | TRY5I | PIR_PASA_GEN_4200034 | 347768 | 305886 |

| Trypsin | TRY5J | PIR_PASA_GEN_4200035 | 347765 | 305887 |

| Trypsin | TRY5K | PIR_estExt_fgenesh1_kg.C_850001 | 347782 | 231482 |

| Trypsin | TRY5L | PIR_NCBI_GNO_8500013 | 347781 | 59836 |

| Trypsin | TRY5M | PIR_NCBI_GNO_24500018 | 347780 | 65745 |

| Chymotrypsin | CHY1A | PIR_PASA_GEN_2900126 | 347760 | 304512 |

| Chymotrypsin | CHY1B | PIR_NCBI_GNO_2900206 | 347750 | 319507 |

| Chymotrypsin | CHY1C | PIR_NCBI_GNO_2900207 | 347751 | 52244 |

| Chymotrypsin | CHY1D | PIR_PASA_GEN_2900062 | 347749 | 52244 |

| Chymotrypsin | CHY1E | PIR_PASA_GEN_2900063 | 347752 | 304463 |

| Chymotrypsin | CHY1F | PIR_NCBI_GNO_2900210 | 347753 | 26258 |

| Chymotrypsin | CHY1G | PIR_PASA_GEN_2900130 | 347754 | 304515 |

| Chymotrypsin | CHY1H | PIR_estExt_fgenesh1_kg.C_290019 | 347757 | 231027 |

| Endoribonuclease | ERNA | PIR_PASA_GEN_12200001 | 347694 | 301221 |

| Endoribonuclease | ERNB | PIR_PASA_GEN_6000032 | 347697 | 307196 |

| Astacin | ACN2 | PIR_NCBI_GNO_18200007 | 347841 | 93694 |

| Peptidase M13 | estExt_Genewise1Plus.C_750105 | 200882 | 200882 | |

| Peptidase M2 | PASA_GEN_6000071 | 307230 | 307230 | |

| Carboxylesterase, type B | PASA_GEN_25200006 | 304160 | 304160 | |

| Sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase | PASA_GEN_2900053 | 304453 | 304453 | |

| Sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase | PASA_GEN_13800028 | 301526 | 301526 | |

| Carboxypeptidase A | CPA1A | estExt_Genewise1Plus.C_150058 | 195011 | 195011 |

| Carboxypeptidase A | CPA1B | NCBI_GNO_1500041 | 315693 | 315693 |

| Vitellogenin | VTG1 | BDE_estExt_Genewise1.C_9580001 | 299677 | 219769 |

| Vitellogenin | VTG2 | PIR_estExt_fgenesh1_pg.C_9580001 | 347667 | 229959 |

| Vitellogenin | VTG2 | PIR_estExt_fgenesh1_pg.C_470029 | 347678 | 226075 |

| Vitellogenin | VTG3 | estExt_fgenesh1_pg.C_470021 | 226068 | 226068 |

| Vitellogenin | VTG4 | PASA_GEN_8300068 | 308693 | 308693 |

| Actin | ACT1A | PIR_PASA_GEN_0400163 | 347740 | 305550 |

| Actin | ACT1B | estExt_fgenesh1_pg.C_1190006 | 228751 | 301040 |

| Actin | ACT1C | PIR_PASA_GEN_0500107 | 347742 | 306442 |

| Actin | ACT1D | PIR_fgenesh1_pm.C_scaffold_66000006 | 347743 | 129328 |

| Actin | ACT2A | PIR_PASA_GEN_0100278 | 347739 | 300012 |

| Actin | ACT2B | PIR_estExt_Genewise1Plus.C_20413 | 347736 | 190689 |

| Actin | ACT2C | PIR_e_gw1.2.692.1 | 347703 | 40361 |

| Myosin | MHC-1 | PIR_7_PIR_NCBI_GNO_0600448 | 347733 | 192727 |

| Myosin | PMY | PIR_estExt_Genewise1.C_2380001 | 347700 | 219409 |

| HSP90 | PASA_GEN_17300027 | 302452 | 302452 | |

| Pyruvate kinase | NCBI_GNO_29900007 | 334106 | 334106 | |

| AAA+ ATPase | PASA_GEN_8000045 | 308570 | 308570 | |

| α-Amylase | AMY | FRA_PASA_GEN_2100059 | 347603 | 303445 |

| Exo-β-1,3-glucanase | EXG5 | PIR_PASA_GEN_1000289 | 347606 | 300436 |

| Cellubiohydrolase | CEL7A | PIR_PASA_GEN_1000209 | 347598 | 300366 |

| Endo-β-1,4-glucanase | CEL9A | PIR_estExt_fgenesh1_kg.C_70001 | 347602 | 230437 |

| β-1,3-glucan-binding protein | PASA_GEN_0200102 | 303036 | 303036 | |

| Endo-β-1,4-mannanase | MAN5A | PIR_PASA_GEN_8600009 | 347627 | 308762 |

| Enolase | ENO | PIR_PASA_GEN_1500033 | 347595 | 301844 |

Putative functions and symbolic names of identified proteins are given in relation to gene model names and protein identification numbers of those loci which were referred to in the present study. DappuDraft protein IDs in bold type indicate manually curated gene models that may differ from those contained in the 'Filtered Models v1.1' set (released by the Joint Genome Institute in July 2007). The Reference DappuDraft gene ID can be used to retrieve the corresponding models from the Filtered Models set.

It is conspicuous, that a separation of cold-induced and cold-repressed proteins by Mr/pI leads to protein groups of similar classification. Almost all of the identified proteins with a reduced expression in the cold (expression reduction by 40–80%) were secretory enzymes involved in protein digestion (spots 31–32 and 36–41, Table 1). These include three trypsins (TRY4B, TRY5F, TRY5L), two chymotrypsins (CHY1A, CHY1C), one astacin (ACN2), and two carboxypeptidases (CPA1A, CPA1B). All these proteins are synthesized as pro-enzymes (zymogens), which are activated by the removal of an N-terminal propeptide (3–11 kDa). Owing to the similarities in their Mr/pI values, these proteins were multiply identified among the analysed spots. In addition, the multiple occurrence of TRY5F and CHY1C in spots with assigned Mr values of 25 and ≈ 30 kDa may be explained by the possible co-presence of pro-enzymes and enzymes. The only non-proteolytic proteins identified among these spots were two secretory proteins (ERNA, ERNB) carrying the characteristic domain of the EndoU/XendoU family of endoribonucleases [13,14]. The spot region 28, which was excised and analyzed in a previous study [12], contained a mixture of enzymes (including peptidases of the family M2 and M13), which made an expression evaluation impossible.

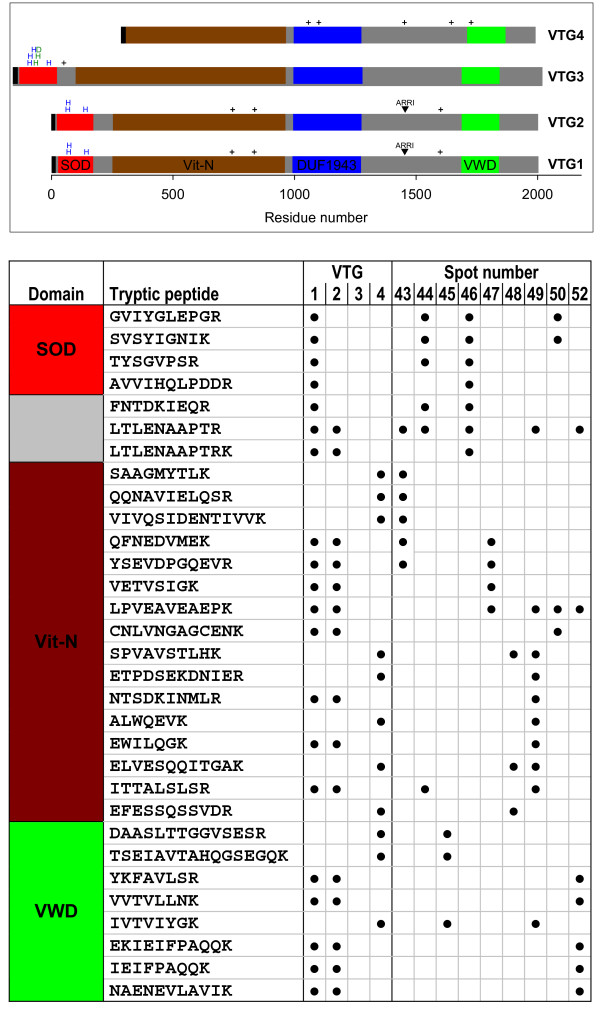

Most dominant among the identified cold-induced proteins were the vitellogenins (VTGs) and actins. These proteins showed a 4–7-fold induction and were detected in ten spots (43–52). The multiple detection of these proteins and the large discrepancies between the experimental (15–40 kDa) and predicted Mr values (actins: 42 kDa, VTGs: 190–220 kDa) indicate that the main share of the cold-induced protein spots in the lower right diagonal half of the gel (Figure 1C; red-colored spots) were proteolytic cleavage fragments. However, it is important to note that VTG cleavage fragments of 65–155 kDa may naturally occur in developing Daphnia embryos (see discussion). The tryptic peptides used for the identification of VTGs covered a large part of the VTG sequences including the superoxide dismutase-like domain (SOD), the large-lipid-transfer module (Vit-N), and the von Willebrand-factor type-D domain (VWD) (Figure 2). None of the tryptic peptides could be allocated to the domain of unkown function (DUF1943) and to the interdomain regions. Based on the high sequence coverage by trypic fragment analysis, two vitellogenins (VTG1, VTG4) could be identified (Figure 2, lower part). Although the present study did not yield any tryptic peptides for the N-terminal SOD-like domain of VTG2, the presence of VTG2 among the analyzed spots cannot be excluded because of the very large sequence identity of VTG2 and VTG1 (98% identity when excluding the SOD-like domain).

Figure 2.

Assignment of protein spots to the vitellogenins of Daphnia pulex. Daphnia vitellogenins (VTGs) are generally composed of an N-terminal large-lipid-transfer-module (Vit-N), a domain of unkown function (DUF1943), and a C-terminal von Willebrand-factor type-D domain (VWD). Of the muliple VTGs of D. pulex, only four are shown in respect to their domain composition (top). Note that VTG1, VTG2 and VTG3 additionally contain a superoxide dismutase-like domain (SOD) at the N-terminus. Interdomain regions are shown in gray, the signal peptide in black. Conserved residues of the SOD for Cu2+ and Zn2+ binding are indicated by blue (histidines) and green characters (histidines, aspartic acid), respectively. Potential N-linked glycosylation sites are indicated by plus signs. 'ARRI' indicates primary cleavage sites between two arginine residues. The lower part lists the tryptic peptides in the order of their appearance in the VTG sequences and in the analyzed spots.

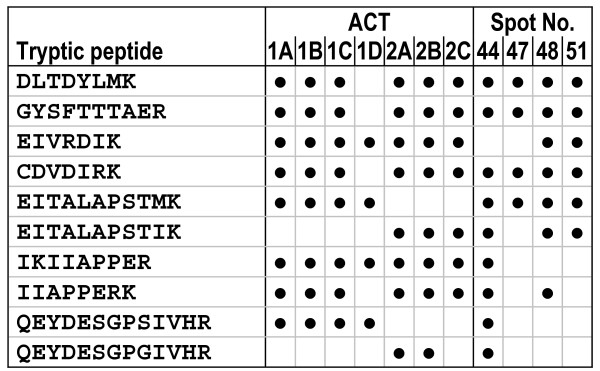

Actins were detected in four spots (44, 47, 48, 51). The tryptic peptides used for the identification of actins (Figure 3) covered only the C-terminal half of the 42-kDa proteins, suggesting that the N-terminal half was proteolytically cleaved during the preparation of whole-animal extracts. Proteolytic cleavage is additionally indicated by the discrepancy between experimental (25–36 kDa) and predicted Mr values (42 kDa). Owing to the high sequence identity (≈ 97%), it was impossible to discriminate the expression of cytoplasmic isoforms (ACT1A-D) and muscle-specific isoforms (ACT2A-C). The lower number of tryptic-peptide assignments and the complete lack of EST evidences for ACT1D and ACT2C, however, suggests that these two actins were probably not expressed.

Figure 3.

Assignment of protein spots to the actin sequences of Daphnia pulex. The D. pulex genome contains seven actin genes which code for cytoplasmic (ACT1A-D) and muscle-specific isoforms (ACT2A-C). The tryptic peptides identified in mass spectrometry are listed in the order of their appearance in the sequence of gene products and gel spots.

A ten-fold up-regulation in the cold was found for an AAA+ adenosine triphosphatase (ATPase associated with diverse cellular activities; [15]), a fragment of which was detected in spot 42. Additional identifications comprised proteolytic cleavage fragments of a molecular chaperone (HSP90, spot 47), the heavy chain of myosin (MHC-1) and a pyruvate kinase (both in spot 48). Since the latter three proteins were co-identified with actins and VTGs in the same spots, it was impossible to assess their induction states.

Among the remaining identifications was a group of carbohydrate-modifying enzymes with a constitutive or reduced expression in the cold. Constitutive expressions showed the exo-β-1,3-glucanase EXG5 (spot 34) and the α-amylase AMY (spot 35). The cold-repressed proteins included a cellubiohydrolase (CEL7A, spot 1), an endo-β-1,4-glucanase (CEL9A, co-localized with paramyosin in spot 19), an endo-β-1,4-mannanase (MAN5A, co-localized with a β-1,3-glucan-binding protein in spot 30), and the enolase ENO (spot 19).

Discussion

As a companion study to a previous investigation of acclimatory adjustments of the Daphnia pulex proteome to hypoxia [12], the effects of two different acclimation temperatures (10°C and 20°C) on the Daphnia pulex proteome were analyzed by 2D gel electrophoresis and mass spectrometry. Temperature acclimation mostly affected the expression of sets of proteins different from those identified under variable oxygen conditions. Several proteins constitutively expressed or subjected to hypoxic induction were also detected in the 2D gels presented here. The specific sets of proteins up- or down-regulated in the cold (10°C) were identified here for the first time.

Cold-induced protein sets I: Egg yolk proteins and precursors

The most dominant group among the cold-induced proteins in D. pulex were the vitellogenins (Table 1). Vitellogenin (VTG) is a precursor of the yolk protein vitellin. It is a lipoglycoprotein that is employed as a vehicle to provide the developing embryo with proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, and other essential resources. In many oviparous animals such as insects and non-mammalian vertebrates, VTG is synthesized in extraovarian tissues (e.g. fat body or liver) and is then transported via the blood/hemolymph to the developing oocytes [16,17]. An exception are the decapod crustaceans which show, in addition to the extraovarian synthesis in the hepatopancreas, an intraovarian synthesis of yolk proteins [18]. Since the VTGs of the branchiopod crustacean Daphnia spp. are more closely related to insect VTGs than to the yolk protein precursors of decapods [19-21], it is reasonable to postulate a vitellogenic tissue that is homologous to the VTG-synthesizing fat body of insects. Although there are some cytological indications for an endogenous synthesis of yolk proteins in amphigonic oocytes [22], the main site of VTG synthesis in Daphnia appears to be the highly polyploid fat cells, which exhibit periodic variations in lipid and glycogen content, cell size and ultrastructure in relation to the parthenogenetic reproduction cycle [22-24].

The screening of the D. pulex genome database suggests 19 loci with VTG-like coding sequences. Two gene products, VTG1 and VTG4, were identified in the present study (Figure 2). The additional expression of VTG2, however, which shares a high sequence similarity with VTG1, cannot be excluded. VTG1 and VTG2 are homologous to the vitellogenins DmagVTG1 and DmagVTG2 of D.magna [25]. As in D. magna, the VTG1 and VTG2 genes are arranged in a tandem array in a back-to-back orientation, which might enable a coordinated hormonal regulation of their transcription [25]. DmagVTG1 and (probably) DmagVTG2 are the most abundant polypeptides in D.magna parthenogenetic eggs at initial stages of development [19]. At least one of the primary cleavage sites is present in VTG1 and VTG2 of D. pulex (Figure 2, top: 'ARRI'). Given the high sequence identity (88–90%) between the corresponding VTGs of both Daphnia species, it is likely that primary cleavage fragments of similar size occur in the developing eggs of D. pulex as well. However, none of these primary cleavage fragments could be detected in full length (65–155 kDa) among the analyzed spots, which contained only smaller VTG fragments of 18–27 kDa, possibly as a consequence of a residual proteolytic activity during the preparation of whole-animal extracts. Alternatively, smaller-than-expected fragments may have arisen prior to extract preparation by an advanced cleavage of yolk material during embryonic development.

The 4–7-fold up-regulation of VTGs in 10°C acclimated D. pulex (Table 1) was an unexpected finding. About 50–100 adult daphnids were randomly sampled irrespective of their reproductive states for single protein extractions. The protein extracts consequently contained contributions from parthenogenetic eggs and embryos in the brood chamber as well as from maternal tissues. A greater share of vitellogenin in the protein extracts from 10°C acclimated animals may therefore result from a greater amount of eggs in the ovaries and the brood pouch or from an increased vitellogenin concentration in the synthesizing tissues, ovaries, eggs and embryos. An inspection of both acclimation groups did not reveal any differences in clutch size or in the share of animals carrying eggs and embryos. Previous findings on the impact of temperature on clutch sizes in Daphnia are ambiguous: there were reports on lowered [9], unchanged [11] or increased [26] clutch sizes in D. magna at lower temperatures. In this study, the protein concentration in the extracts was quantified and the extracts were appropriately diluted to guarantee the application of identical amounts of protein (142 μg protein) per 2D gel. Compared to the extracts from 20°C acclimated animals, the extracts from 10°C acclimated animals had a 50% higher protein concentration. The slower growth and development of D. pulex in the cold may possibly result in a higher concentration of whole-body protein with the VTGs particularly contributing to this effect.

A striking feature of VTG1-VTG3 is the presence of an N-terminal superoxide dismutase (SOD)-like domain (Figure 2), which is related to the Cu/Zn SODs of prokaryotes [25]. The catalytic activity of this class of SODs depends on Zn2+ and Cu2+ ions, which are coordinated by six histidine residues and one aspartic residue [27]. These residues are still present in VTG3. VTG1 and VTG2 have lost all Zn-binding residues and one of the four histidine residues involved in Cu2+ binding. Functional studies on the purified yolk-protein complexes of D. magna revealed some residual SOD activity per constituent VTG chain (≈ 1%, in comparison to the activity of a bovine Cu/Zn SOD) [19]. Because of the great number of VTG loci in the D. pulex genome and the presence of an apparently intact SOD-like domain in VTG3 (for which EST evidence is available), it is difficult to analyze any (residual) detoxifying capacity of VTG1 and VTG2. Future experimental studies will be necessary to evaluate the suggested implications of the SOD-like domains of the Daphnia VTGs in superoxide detoxification [19] and copper binding/transportation [25].

Cold-induced protein sets II: Cytoskeleton and muscle proteins

Actins were the second large set of proteins up-regulated in the cold (Table 1). Although actins were often co-identified with VTGs during the proteomic analysis, the identification of only actin in spot 51 indicates the manifold induction of these proteins. Actin is a highly conserved protein. As major building block of the cytoskeleton and the thin filaments of myofibrils, it is involved in many important cell functions including cell motility, muscle contraction and intracellular transport. Actin generally occurs in multiple isoforms which are expressed in a tissue- and development-specific manner [28]. Compared to the genomes of human, mouse, and fly, which contain six actin loci [29], seven actin loci are present in the genome of D. pulex (Figure 3). Four of the predicted amino acid sequences (ACT1A, ACT1B, ACT1C, ACT1D) of D. pulex are related to cytoplasmic actin isoforms (5C, 42A) of Drosophila melanogaster [28,30] The other three D. pulex sequences (ACT2A, ACT2B, ACT2C) are similar to the muscle-specific actin isoforms (57B, 79B, 87E, 88F) of Drosophila. The ACT2C gene is very likely a pseudogene as it lacks about 50% of the actin sequence information. Among the putative cytoplasmic actins of D.pulex, ACT1D possesses less conserved sequence characteristics. The complete lack of EST support for ACT1D and ACT2C suggests that only three cytoplasmic and two muscle-specific actin isoforms are expressed in D. pulex. Because of high sequence identity, a discrimination between these isoforms was not possible in the present study.

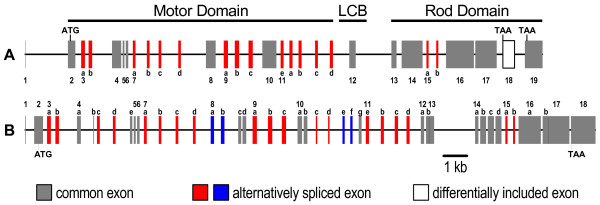

Two additional muscle proteins, the heavy chain(s) of muscle myosin (e.g. MHC-1) and a paramyosin (PMY), were identified on the 2D gels (Table 1). These proteins were detected in separate spots together with other proteins, which make an assessment of induction state difficult. The MHC gene of D. pulex deserves special attention as it shares interesting features with the MHC gene of Drosophila melanogaster (Figure 4) [58]. In contrast to many complex organisms with physiologically distinct muscle types, in which MHC isoforms are encoded by multiple genes, at least 15 muscle MHC isoforms are expressed in Drosophila from a single-copy gene by alternative splicing. Many of these isoforms show tissue- or development-specific expression [29,31,32] The D. pulex genome also contains a single-copy muscle MHC gene, whose exon structure shows similarity to the MHC gene structure of Drosophila. Given the complexity of the MHC gene and the, at present, only scarcely available transcript information, no conclusions can be drawn about the number and identity of MHC isoforms in D. pulex.

Figure 4.

Myosin genes of Drosophila melanogaster and Daphnia pulex. (A) The myosin heavy chain (MHC) gene of D. melanogaster (FlyBase annotation ID:CG17927) showing the common and alternatively spliced exons (LCB, light chain-binding domain) [31,32,58] (B) Putative architecture of the muscle MHC gene of D. pulex (scaffold_6: 2047569–2071828). ATG and TAA indicate the start of translation and the stop codon, respectively. In the Drosophila MHC transcripts, the sequence of the terminal exon can be replaced by that of the 'differentially included exon'.

In general, a reduction of ambient temperature is immediately responded by a decrease of muscular performance in Daphnia. For example, the limb beating rate decreases which in turn reduces the uptake of oxygen and food. Likewise, the heart rate decreases with the consequence of a reduced hemolymph transport of substrates [3,5,8,11]. However, the heart and limb beating rates were frequently not much different in Daphnia species at identical ambient and acclimation temperatures of 10–12°C or 18–20°C [3,5]. In addition, maximum swimming activity of 10°C acclimated D. magna was found to be similar to that of 20°C acclimated animals [6]. In poikilothermic animals, the concentration of enzymes involved in cellular metabolism frequently increases with decreasing acclimation temperatures to prevent a too strong depression of metabolic rate (metabolic cold adaptation) [7]. Such a type of long-term compensatory control may apply as well to the cytoskeletal or muscular proteins to maintain a similar level of muscular performance at lower acclimation temperatures.

Cold-repressed protein sets: Proteolytic enzymes

In the cold, different classes of enzymes mainly involved in extracellular digestion were down-regulated. In other words, the capacity for the digestion of proteins increased with acclimation temperature (Table 1). The identification comprised serine peptidases of the chymotrypsin family S1, metallo peptidases of the astacin/adamalysin family M12, and the carboxypeptidase A family M14 (classification according to the MEROPS database) [33]. A screening of the D. pulex genome database revealed more than 200 loci with coding sequences for serine-peptidase domains, 36 loci with astacin-like coding sequences, and 30 loci coding for carboxypeptidase-like domains. However, not all predicted gene products are involved in digestive processes. Serine proteases of the chymotrypsin family, for example, are involved in multiple physiological functions such as digestion, degradation, blood clotting, immunity, and development [34]. Nevertheless, the sheer number of peptidase genes in the D. pulex genome indicates large-scaled gene family expansions that might reflect specific adaptations to the lifestyle of a planktonic filter feeder in a highly variable aquatic environment [35].

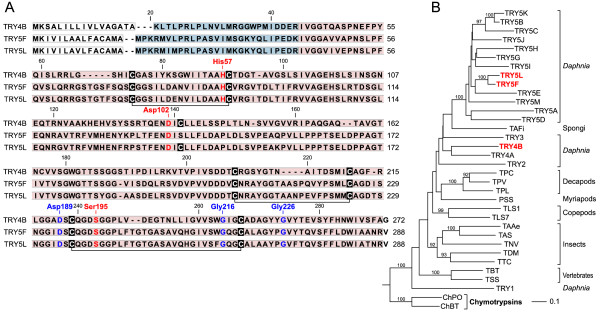

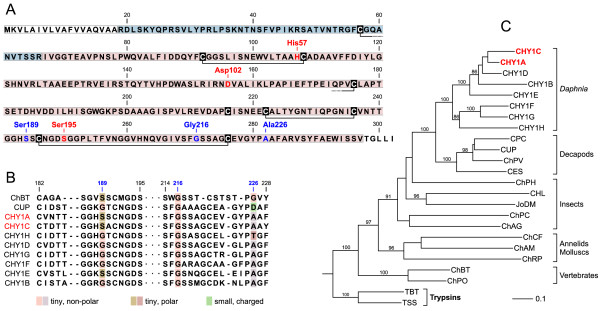

The identified serine peptidases comprised three trypsin-like proteins (TRY4B, TRY5F, TRY5L) and two chymotrypsin-like proteins (CHY1A, CHY1C). The presence of N-terminal signal and propeptide sequences classifies these candidates as secretory proteins that are synthesized as inactive pro-enzymes (zymogens). All sequences contain the characteristic residues of the catalytic triade (His57, Asp102, Ser195; Figures 5A and 6A) [59]. Substrate specificity is usually determined by three residues at the S1 site which is a pocket adjacent to Ser195 [36]. The S1-site residues of trypsin are Asp189, Gly216 and Gly226 [37]. All three residues are present in the detected trypsins of D. pulex (Figure 5A). Multiple-sequence alignment (Additional Files 1, 2) and phylogenetic-tree analysis of serine peptidase sequences from the D. pulex genome database revealed many other trypsin-like proteins. Two of them (TRY5F, TRY5L) together with 11 other sequences from D.pulex form a monophyletic cluster (Figure 5B). In CHY1A and CHY1C, the primary specificity residues comprise Ser189, Gly216 and Ala226 (Figure 6B). The first two residues are the same as in bovine chymotrypsin [37]. At the third position, Ala226 replaces the typical Gly226. These two residues are similar in shape and electrostatic character, suggesting that substrate specificity is not significantly altered by this replacement. CHY1A and CHY1C together with six additional chymotrypsin-like proteins from D. pulex form a monophyletic cluster (Figure 6C). D. pulex chymotrypsins are closely related to the C-type brachyurins (MEROPS classification: S01.122), which include the decapod chymotrypsins and collagenolytic proteases [38-42] C-type brachyurins are characterized by a broad substrate specificity [41]. Among the D.pulex chymotrypsins, an even enlarged range of substrate specificity may be assumed because of the sporadic replacements of Ser189 and Gly226 by residues of different electrostatic properties (Figure 6B).

Figure 5.

Trypsin-like proteins of Daphnia pulex. (A) Derived amino-acid sequence and domain structure of three trypsin genes (TRY4B, TRY5F, and TRY5L) from D. pulex. Predicted domain characteristics include the N-terminal signal peptide (white frame), the propeptide (blue), the chymotrypsin-like domain (red), the conserved disulfide bridges (connected cysteine residues), the catalytic triade (red characters), and substrate-specificity residues (blue characters). Residues numbering was taken from bovine chymotrypsinogen [59]. (B) Phylogenetic tree for selected trypsin-like sequences based on a multiple-sequence alignment of the trypsin-like domain including three adjacent propeptide residues (see Additional file 1). Proteins detected in the present study are labeled in red. The tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining algorithm and was rooted with chymotrypsin sequences. Bootstrap analysis was performed with 100 replicates (boostrap values <80 are omitted). Abbreviations and NCBI accession numbers: TRY1-TRY5M, Daphnia pulex; TAFi, trypsin from Aplysina fistularis (AAO12215); TPC, trypsin from Paralithodes camtschaticus (AAL67442); TPV, trypsin from Litopenaeus vannamei (CAA75311); TPL, trypsin from Pacifastacus leniusculus (CAA10915); PSS, plasminogen activator from Scolopendra subspinipes (AAD00320); TLS1 and TLS7, trypsin from Lepeophtheirus salmonis (CAH61270, AAP55755); TAAe, trypsin from Aedes aegypti (P29787); TAS, trypsin from Anopheles stephensi (AAB66878); TNV, trypsin from Nasonia vitripennis (XP_001599779); TDM, trypsin from Drosophila melanogaster (P04814); TTC, trypsin from Tribolium castaneum (XP_967332); TBT, trypsin precursor from Bos taurus (Q29463); TSS, trypsin-1 precursor from Salmo salar (P35031); ChPO, chymotrypsinogen 2 from Paralichthys olivaceus (Q9W7Q3); ChBT, chymotrypsinogen A from Bos taurus (P00766).

Figure 6.

Chymotrypsin-like proteins of Daphnia pulex. (A) Derived amino-acid sequence and domain structure of the CHY1A gene from D. pulex. Predicted domain characteristics include the N-terminal signal peptide (white frame), the propeptide (blue), the chymotrypsin-like domain (red), the conserved disulfide bridges (connected cysteine residues), the catalytic triade (red characters), and substrate-specificity residues (blue characters). (B) Sequence alignment of chymotrypsin-like enzymes showing the substrate recognition site with the primary specificity (S1) residues at 189, 216 and 226 (numbering system of bovine chymotrypsinogen; [59]). The shape (tiny, small) and electrostatic character (non-polar, polar, charged) of S1 residues is indicated by color shading. (C) Phylogenetic tree for selected chymotrypsin-like sequences based on a multiple-sequence alignment of the chymotrypsin-like domain including four adjacent propeptide residues (see Additional file 2). Proteins detected in the present study are labeled in red (CHY1A and CHY1C). The tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining algorithm and was rooted with trypsin sequences. Bootstrap analysis was performed with 100 replicates (boostrap values <80 are omitted). Abbreviations and NCBI accession numbers: CHY1A-H, Daphnia pulex; CPC, collagenolytic protease from Paralithodes camtschaticus (AAL67441); CUP, collagenolytic protease from Celuca pugilator (P00771); ChPV, chymotrypsin BII from Litopenaeus vannamei (CAA71673); CES, protease from Euphausia superba [39]; ChPH, protease from Pediculus humanus corporis (AAV68346); CHL, collagenase precursor from Hypoderma lineatum (P08897); JoDM, Jonah 43E from Drosophila melanogaster (NP_724699); ChPC, chymotrypsin precursor from Phaedon cochleariae (O97398); ChAG, protease from Anopheles gambiae (AGAP005663-PA); ChCF, protease from Chlamys farreri (ABB89132); ChAM, chymotrypsinogen from Arenicola marina (CAA64472); ChRP, serine peptidase 2 from Radix peregra (ABL67951); ChBT, chymotrypsinogen A from Bos taurus (P00766); ChPO, chymotrypsinogen 2 from Paralichthys olivaceus (Q9W7Q3); TBT, trypsin precursor from Bos taurus (Q29463); TSS, trypsin-1 precursor from Salmo salar (P35031).

The MS analysis could identify and assign only those tryptic peptides which were specific for mature proteolytic enzymes. No support was obtained for the N-terminal signal peptides, which direct the nascent proteins to the secretory pathway, and for the pro-peptides, which shield the active sites in the immature trypsinogens or chymotrypsinogens (Figure 5 and 6). Therefore, it can be assumed that the proteases originated from the gut lumen, which (in D. magna) contain the major share of proteases [43]. During the preparation of whole-animal extracts for the present study, intestinal proteins such as proteases are included along with those from other tissues. The presence of high amounts of proteases causes methodical problems [12], resulting in a contribution of proteolytic fragments to the observed protein spots. On the other hand, the high concentration of proteases being present in the whole-animal extracts documents a high digestive capacity for nutritional protein resources which increases with acclimation temperature. The marked induction of proteases between 10°C and 20°C acclimated animals probably reflects a higher rate of protein turnover at the higher temperature. Between identical ambient and acclimation temperatures of 10 and 20°C, the oxygen consumption rate of D. magna increased by 30% [4] and that of D. pulex by 60% (unpublished results). Accordingly, the observed induction of proteolytic capacity by a factor of 2–5 (Table 1: trypsin, chymotrypsin) may reflect at least in parts the temperature effect on metabolic rate in acclimated D. pulex. In addition, higher needs for proteins may arise at higher temperatures due to modifications in the allocation and/or requirement of nutrient resources (e.g. enlarged protein needs for growth and reproduction). Previous reports on the impact of temperature on clutch sizes in Daphnia were ambiguous; however, a reduction of vitellogenin and protein concentration was detected in this study between 10°C and 20°C acclimation (see Discussion above). At 20°C acclimation (in comparison to 10°C acclimation), the higher growth rate (and possibly a higher reproduction rate) of D. pulex and/or a faster passage of nutrients through the digestive tract with possibly incomplete nutrient digestion and reduced assimilation efficiency goes hand in hand with a reduced concentration of total protein and vitellogenin in the animals. These relationships at least indicate higher demands for proteins at 20°C acclimation, which may explain the induction of intestinal proteases.

Miscellaneous proteins

Among the miscellaneous proteins with an unambiguous (one spot-one protein) identification were several carbohydrate-modifying enzymes, which were either down-regulated in the cold (cellubiohydrolase, enolase) or remained constitutively expressed (α-amylase, exo-β-1,3-glucanase), and an AAA+ ATPase, which was strongly up-regulated under cold conditions. AAA+ ATPases are molecular machines that are involved in a variety of cellular functions including vesicle transport, organelle assembly, membrane dynamics and protein unfolding [15]. They contribute to the non-destructive recycling of proteins, play an important role in protein quality control (e.g. chaperone function), and can act as microtubule motor proteins or microtubule-severing enzymes [15].

Conclusion

Major sets of proteins (egg yolk proteins and precursors, cytoskeleton and muscle proteins, proteolytic enzymes) were differentially expressed in 10°C and 20°C acclimated D. pulex. Compared to 10°C, the acclimation to 20°C was associated with a decrease of vitellogenins, actins and even total protein concentration, as well as with an increase of proteases. The increase of proteolytic enzymes probably reflects a higher cellular demand for amino acids, which may result from higher growth and reproduction rates and/or from a lower efficiency of intestinal protein digestion/assimilation. The decrease of protein reserves (vitellogenins, actins or total protein) also indicates an increasing bottle-neck in the amino acid supply of cells. Conversely, the acclimation to cold conditions induced an increase in protein concentration which may be related to metabolic cold adaptation, a phenomenon for which multiple physiological support exists. Metabolic cold adaptation is a compensatory mechanism which ensures a relative constancy of metabolic rate and muscular performance. Particularly, the increase of actins in the cold maybe related to a compensatory control of muscular proteins to establish a relative constancy of muscular activity and performance.

Methods

Acclimation conditions

Water fleas, Daphnia pulex, were raised in the laboratory as described previously [12]. The animals were acclimated at least for three weeks (mostly months) to 10°C or 20°C at normoxic conditions (100% air saturation; oxygen partial pressure: 20 kPa), which was obtained by mild aeration using an aquarium pump. To guarantee an adequate nutrient supply at each acclimation temperature, animals were fed with green algae (Desmodesmus subspicatus) ad libitum (>1 mg C L-1) every second day. Only adult females were used for protein extraction.

Proteomics

Protein extraction, two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and statistical analysis of protein expression were carried out as described previously [12]. Spots showing a sufficient size and staining intensity (relative spot volume, Vrel > 0.1%) and differential expression between 10°C or 20°C acclimation, were excised from representative gels and subjected to in-gel digestion using trypsin and mass spectrometric analysis (nano-HPLC-ESI-MS/MS) [12]. Ratios of relative spot volumes at both temperatures were considered as induction factors. Several spots of high but constitutive expression were also included in the analysis.

Identification and characterization of proteins

Proteins were identified by correlating the ESI-MS/MS spectra with the "Frozen Gene Catalog" of the D. pulex v1.1 gene builds (July, 2007) [2] using the MOWSE-algorithm as implemented in the MS search engine MASCOT (Matrix Science Ltd., London, UK) [44]. The "Frozen Gene Catalog" contains all manual curations as of July 3, 2007 as well as automatically annotated models chosen from the "Filtered Models" v1.1 set. "Filtered Models" is the filtered set of models representing the best gene model for each locus. The putative function of identified proteins was inferred by sequence homology either from the automated blastp search provided by Joint Genome Institute [2] or from a manual blastp search provided by NCBI. Derived protein sequences were checked for the presence of N-terminal signal sequences using the SignalP V3.0 server [45-47]. The theoretical molecular weight (Mr) and isolectric point (pI) of mature proteins (without N-terminal signal peptide) was calculated using the ExPASy Proteomics tool "Compute pI/MW" [48-50]. Characteristic domains of protein families were identified using the conserved domain database (CDD) and search engine v2.13 at NCBI [51,52]. Putative N-glycosylation sites in vitellogenins were predicted using the NetNGlyc 1.0 Server [53].

Sequence alignments and phylogenetic analysis

Multiple-sequence alignments were performed using the T-Coffee algorithm [54-56]. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using the neighbor-joining algorithm [57] and a bootstrap analysis with 100 replicates.

Abbreviations

Mr: molecular weight; pI: isolectric point; Vrel: relative spot volume.

Authors' contributions

SS and MK were involved in the culturing of animals and performed the protein extraction as well as the 2D-PAGE. 2D-gel image analysis was carried out by TL, BZ and RP. JM and CF were responsible for mass spectrometry and protein identification. RP and SS retrieved the information contained in Table 1. Figures were designed by RP. The annotation and manual curation of identified genes, the sequence alignments and phylogenetic analysis were performed by RP. BZ, RJP, RP and SS conceived and coordinated the study, and prepared the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Multiple sequence alignment of trypsin-like sequences. The multiple-sequence alignment was performed using the T-Coffee algorithm [54]. NCBI accession numbers for the symbolic sequence names are listed in the Figure legend 5.

Multiple sequence alignment of chymotrypsin-like sequences. The multiple-sequence alignment was performed using the T-Coffee algorithm [54]. NCBI accession numbers for the symbolic sequence names are listed in the Figure legend 6.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Simone König from the Integrated Functional Genomics (University of Münster), and Marco Matthes (at that time at the Technical University Dresden) for providing the animals used for the clonal culture. We are also grateful for support from DECODON GmbH (BioTechnikum Greifswald). The Proteom Centrum Tübingen is supported by the Ministerium für Wissenschaft und Kunst, Landesregierung Baden-Württemberg.

The sequencing and portions of the analyses were performed at the DOE Joint Genome Institute under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science, Biological and Environmental Research Program, and by the University of California, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory under Contract No. W-7405-Eng-48, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231, Los Alamos National Laboratory under Contract No. W-7405-ENG-36 and in collaboration with the Daphnia Genomics Consortium, DGC http://daphnia.cgb.indiana.edu. Additional analyses were performed by wFleaBase, developed at the Genome Informatics Lab of Indiana University with support to Don Gilbert from the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health. Coordination infrastructure for the DGC is provided by The Center for Genomics and Bioinformatics at Indiana University, which is supported in part by the METACyt Initiative of Indiana University, funded in part through a major grant from the Lilly Endowment, Inc. Our work benefits from, and contributes to the Daphnia Genomics Consortium.

Contributor Information

Susanne Schwerin, Email: susanne.schwerin@freenet.de.

Bettina Zeis, Email: zeis@uni-muenster.de.

Tobias Lamkemeyer, Email: tobias.lamkemeyer@uni-tuebingen.de.

Rüdiger J Paul, Email: paulr@uni-muenster.de.

Marita Koch, Email: marita@uni-muenster.de.

Johannes Madlung, Email: johannes.madlung@uni-tuebingen.de.

Claudia Fladerer, Email: claudia.fladerer@uni-tuebingen.de.

Ralph Pirow, Email: pirow@uni-muenster.de.

References

- wFleaBase Daphnia waterflea genome database http://wFleaBase.org

- JGI Joint Genome Institute http://www.jgi.doe.gov/Daphnia/

- Pinkhaus O, Schwerin S, Pirow R, Zeis B, Buchen I, Gigengack U, Koch M, Horn W, Paul RJ. Temporal environmental change, clonal physiology and the genetic structure of a Daphnia assemblage (D. galeata-hyalina hybrid species complex) Freshwater Biol. 2007;52:1537–1554. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2427.2007.01786.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lamkemeyer T, Zeis B, Paul RJ. Temperature acclimation influences temperature-related behaviour as well as oxygen-transport physiology and biochemistry in the water flea Daphnia magna. Can J Zool. 2003;81:237–249. doi: 10.1139/z03-001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paul RJ, Lamkemeyer T, Maurer J, Pinkhaus O, Pirow R, Seidl M, Zeis B. Thermal acclimation in the microcrustacean Daphnia: a survey of behavioural, physiological and biochemical mechanisms. J Therm Biol. 2004;29:655–662. doi: 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2004.08.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zeis B, Maurer J, Pinkhaus O, Bongartz E, Paul RJ. A swimming activity assay shows that the thermal tolerance of Daphnia magna is influenced by temperature acclimation. Can J Zool. 2004;82:1605–1613. doi: 10.1139/z04-141. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hochachka PW, Somero GN. Biochemical adaptation: Mechanism and process in physiological evolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lampert W. Feeding and nutrition in Daphnia. In: Peters RH, DeBernardi R, editor. Memorie dell'Istituto Italiano di Idrobiologia, Daphnia. Vol. 45. Pallanza: Istituto Italiano di Idrobiologia; 1987. pp. 143–192. [Google Scholar]

- Goss LB, Bunting DL. Daphnia development and reproduction – responses to temperature. J Therm Biol. 1983;8:375–380. doi: 10.1016/0306-4565(83)90025-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lampert W, Trubetskova I. Juvenile growth rate as a measure of fitness in Daphnia. Funct Ecol. 1996;10:631–635. doi: 10.2307/2390173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giebelhausen B, Lampert W. Temperature reaction norms of Daphnia magna: the effect of food concentration. Freshwater Biol. 2001;46:281–289. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2427.2001.00630.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zeis B, Lamkemeyer T, Paul RJ, Nunes F, Schwerin S, Koch M, Schütz W, Madlung J, Fladerer C, Pirow R. Acclimatory responses of the Daphnia pulex proteome to environmental changes. I. Chronic exposure to hypoxia affects the oxygen transport system and carbohydrate metabolism. BMC Physiol. 2009;9:7. doi: 10.1186/1472-6793-9-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renzi F, Caffarelli E, Laneve P, Bozzoni I, Brunori M, Vallone B. The structure of the endoribonuclease XendoU: From small nuclear RNA processing to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:12365–12370. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602426103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worrall JAR, Luisi BF. Information available at cut rates: structure and mechanism of ribonucleases. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2007;17:128–137. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roehl White S, Lauring B. AAA+ ATPases: Achieving diversity of function with conserved machinery. Traffic. 2007;8:1657–1667. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sappington TW, Raikhel AS. Molecular characteristics of insect vitellogenins and vitellogenin receptors. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 1998;28:277–300. doi: 10.1016/S0965-1748(97)00110-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano M, Rosanova P, Anteo C, Limatola E. Vertebrate yolk proteins: a review. Mol Reprod Dev. 2004;69:109–116. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avarre J-C, Michelis R, Tietz A, Lubzens E. Relationship between vitellogenin and vitellin in a marine shrimp (Penaeus semisulcatus) and molecular characterization of vitellogenin complementary DNAs. Biol Reprod. 2003;69:355–364. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.011627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato Y, Tokishita S, Ohta T, Yamagata H. A vitellogenin chain containing a superoxide dismutase-like domain is the major component of yolk proteins in cladoceran crustacean Daphnia magna. Gene. 2004;334:157–165. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smolenaars MMW, Madsen O, Rodenburg KW, Horst DJ Van der. Molecular diversity and evolution of the large lipid transfer protein superfamily. J Lipid Res. 2006;48:489–502. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R600028-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avarre J-C, Lubzens E, Babin PJ. Apolipocrustacein, formerly vitellogenin, is the major egg yolk precursor in decapod crustaceans and is homologous to insect apolipophorin II/I and vertebrate apolipoprotein B. BMC Evol Biol. 2007;7:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaffagnini F, Zeni C. Considerations on some cytological and ultrastructural observations on fat cells in Daphnia (Crustacea, Cladocera) Boll Zool. 1986;53:33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Jäger G. Ueber den Fettkörper von Daphnia magna. Z Zellforsch. 1935;22:89–131. doi: 10.1007/BF00387983. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sterba G. Zytologische Untersuchungen an grosskernigen Fettzellen von Daphnia pulex unter besonderer Berücksichtigung des Mitochondrien-Formwechsels. Z Zellforsch. 1956;44:456–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokishita S, Kato Y, Kobayashi T, Nakamura S, Ohta T, Yamagata H. Organization and repression by juvenile hormone of a vitellogenin gene cluster in the crustacean, Daphnia magna. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;345:362–370. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.04.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee D, Ebert D. The interactive effects of temperature, food level and maternal phenotype on offspring size in Daphnia magna. Oecologia. 1996;107:189–196. doi: 10.1007/BF00327902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordo D, Djinovic K, Bolognesi M. Conserved patterns in the Cu, Zn superoxide dismutase family. J Mol Biol. 1994;238:366–386. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Röper K, Mao Y, Brown NH. Contribution of sequence variation in Drosophila actins to their incorporation into actin-based structures in vivo. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:3937–3948. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper SI, Thuma JB. Invertebrate muscles: muscle specific genes and peptides. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:1001–1060. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00019.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyrberg EA, Fyrberg CC, Biggs JR, Saville D, Beall CJ, Ketchum A. Functional nonequivalence of Drosophila actin isoforms. Biochem Genet. 1998;36:271–287. doi: 10.1023/A:1018785127079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George E, Ober MB, Emerson CP. Functional domains of the Drosophila melanogaster muscle myosin heavy-chain gene are encoded by alternatively spliced exons. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:2957–2974. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.7.2957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swank DM, Wells L, Kronert WA, Morrill GE, Bernstein SI. Determining structure/function relationships for sarcomeric myosin heavy chain by genetic and transgenic manipulation of Drosophila. Microsc Res Techniq. 2000;50:430–442. doi: 10.1002/1097-0029(20000915)50:6<430::AID-JEMT2>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawlings ND, Morton FR, Barrett AJ. MEROPS: the peptidase database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D270–D272. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krem MM, Rose T, Di Cera E. Sequence determinants of function and evolution in serine proteases. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2000;10:171–176. doi: 10.1016/S1050-1738(00)00068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colbourne JK, Eads BD, Shaw J, Bohuski E, Bauer DJ, Andrews J. Sampling Daphnia's expressed genes: preservation, expansion and invention of crustacean genes with reference to insect. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:217. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedstrom L. Serine protease mechanism and specificity. Chem Rev. 2002;102:4501–4523. doi: 10.1021/cr000033x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perona JJ, Craik CS. Structural basis of substrate specificity in the serine proteases. Protein Sci. 1995;4:337–360. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560040301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin DC, Kristjánsdóttir S, Gudmundsdóttir Á. Increasing the thermal stability of euphauserase. A cold-active and multifunctional serine protease from antarctic krill. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:131. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.01857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristjánsdóttir S, Gudmundsdóttir Á. Propeptide dependent activation of the antarctic krill euphauserase precursor produced in yeast. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:2632–2639. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudmundsdóttir Á. Cold-adapted and mesophilic brachyurins. Biol Chem. 2002;383:1125–1131. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudenskaya GN. Brachyurins, serine collagenolytic enzymes from crabs. Rus J Bioorg Chem. 2003;29:101–111. doi: 10.1023/A:1023248113184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudenskaya GN, Kislitsin YA, Rebrikov DV. Collagenolytic serine protease PC and trypsin PC from king crab Paralithodes camtschaticus: cDNA cloning and primary structure of the enzymes. BMC Struct Biol. 2004;4:2. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Elert E, Agrawal MK, Gebauer C, Jaensch H, Bauer U, Zitt A. Protease activity in gut of Daphnia magna: evidence for trypsin and chymotrypsin enzymes. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;137:287–296. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2003.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins DN, Pappin DJC, Creasy DM, Cottrell JS. Probability-based protein identification by searching sequence data bases using mass spectrometric data. Electrophoresis. 1999;20:3551–3567. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(19991201)20:18<3551::AID-ELPS3551>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SignalP 3.0 http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/

- Bendtsen JD, Nielsen H, von Heijne G, Brunak S. Improved prediction of signal peptides: SignalP 3.0. J Mol Biol. 2004;340:783–795. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuelsson O, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. Locating proteins in the cell using TargetP, SignalP, and related tools. Nature Protocols. 2007;2:953–971. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compute pI/Mw tool http://www.expasy.ch/tools/pi_tool.html

- Bjellqvist B, Basse B, Olsen E, Celis JE. Reference points for comparisons of two-dimensional maps of proteins from different human cell types defined in a pH scale where isoelectric points correlate with polypeptide compositions. Electrophoresis. 1994;15:529–539. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150150171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasteiger E, Hoogland C, Duvaud S, Wilkins MR, Appel RD, Bairoch A. Protein Identification and Analysis Tools on the ExPASy Server. In: Walker JM, editor. The Proteomics Protocols Handbook. Totowa: Humana Press; 2005. pp. 571–607. [Google Scholar]

- CDD a Conserved Domain Database and Search Service http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/cdd.shtml

- Marchler-Bauer A, Anderson JB, Derbyshire MK, DeWeese-Scott C, Gonzales NR, Gwadz M, Hao L, He S, Hurwitz DI, Jackson JD, Ke Z, Krylov D, Lanczycki CI, Liebert CA, Liu C, Lu F, Lu S, Marchler GH, Mullokandov M, Song JS, Thanki N, Yamashita RA, Yin JJ, Zhang D, Bryant SH. CDD: a conserved domain database for interactive domain family analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;35:D237–D240. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NetNGlyc 1.0 Server http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/NetNGlyc/

- TCoffee http://www.tcoffee.org/

- Notredame C, Higgins DG, Heringa J. T-Coffee: a novel method for fast and accurate multiple sequence aligment. J Mol Biol. 2000;302:205–217. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poirot O, O'Toole E, Notredame C. Tcoffee@igs: a web server for computing, evaluating and combining multiple sequence alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3503–3506. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method – a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polyák E, Standiford DM, Yakopson V, Emerson CP, Franzini-Armstrong C. Contribution of myosin rod protein to structural organization of adult and embryonic muscles in Drosophila. J Mol Biol. 2003;331:1077–1091. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00827-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer J. Comparative modeling methods: Application to the family of the mammalian serine proteases. Proteins Struct Funct Genet. 1990;7:317–334. doi: 10.1002/prot.340070404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Multiple sequence alignment of trypsin-like sequences. The multiple-sequence alignment was performed using the T-Coffee algorithm [54]. NCBI accession numbers for the symbolic sequence names are listed in the Figure legend 5.

Multiple sequence alignment of chymotrypsin-like sequences. The multiple-sequence alignment was performed using the T-Coffee algorithm [54]. NCBI accession numbers for the symbolic sequence names are listed in the Figure legend 6.