Abstract

Dopamine (DA) is well-recognized for its determinant role in the modulation of various brain functions. DA was also found in in vitro isolated invertebrate preparations to activate per se the central pattern generator for locomotion. However, it is less clear whether such a role as an activator of central neural circuitries exists in vertebrate species. Here, we studied in vivo the effects induced by selective DA receptor agonists and antagonists on hindlimb movement generation in mice completely spinal cord-transected (Tx) at the low-thoracic level (Th9/10). Administration of D1/D5 receptor agonists (0.5–2.5 mg kg−1, i.p.) was found to acutely elicit rhythmic locomotor-like movements (LMs) and non-locomotor movements (NLMs) in untrained and non-sensory stimulated animals. Comparable effects were found in mice lacking the D5 receptor (D5KO) whereas D1/D5 receptor antagonist-pretreated animals (wild-type or D5KO) failed to display D1/D5 agonist-induced LMs. In contrast, administration of broad spectrum or selective D2, D3 or D4 agonists consistently failed to elicit significant hindlimb movements. Overall, the results clearly show in mice the existence of a role for D1 receptors in spinal network activation and corresponding rhythmic movement generation.

Dopamine (DA) is a neuromodulatory transmitter present in both the invertebrate and vertebrate nervous systems. In mammals, DA is produced in several areas of the brain (e.g. substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area) and its actions are mediated by five receptor subtypes – D1-like (D1, D5) and D2-like (D2, D3, D4) (Jaber et al. 1996; Missale et al. 1998). The spinal cord is known to receive dopaminergic projections originating from brain areas including the hypothalamic A11 region and substantia nigra (Bjorklund & Skagerberg, 1979; Commissiong et al. 1979; Hokfelt et al. 1979; Skagerberg & Lindvall, 1985). Corresponding DA terminal immunolabelling (Holstege et al. 1996) and all subtypes of DA receptors (mRNAs and proteins) were reported in the rat and mouse spinal cord (Zhu et al. 2007, Zhu et al.2008).

Although DA in the brain has been shown to contribute to the modulatory control of motivation, learning, addiction and fine motor movement (Girault & Greengard, 2004), it remains largely unclear what roles DA may play in the spinal cord. Evidence suggesting some roles in the modulatory control of nociception (Fleetwood-Walker et al. 1988; Clemens & Hochman, 2004), plasticity (i.e. LTP, Yang et al. 2005) and spinal-mediated reflexes (Carp & Anderson, 1982; Clemens & Hochman, 2004) has been reported. However, additional effects are likely to exist given the extent and widespread distribution of DA receptors found throughout the mammalian spinal cord.

Along this line of evidence, it has been shown in in vitro isolated invertebrate models that DA can potently activate per se central pattern generator (CPG) neurons. For instance, bath application of DA was found to induce stable fictive locomotor rhythms in the isolated pond snail system (Tsyganov & Sakharov, 2000). Comparable results were reported in the in vitro isolated preparations from leeches where bath-applied DA robustly elicited episodes of fictive locomotor-like patterns and rhythms that closely resemble those found in muscles during real locomotion (Puhl & Mesce, 2008). In the crustacean stomatogastric ganglion system (pyloric network), DA was found to modulate motor patterns and to induce pacemaker oscillations in specific subpopulations of neurons (for review, see Harris-Warrick et al. 1998). Further demonstrating a key role in invertebrate motor and locomotor rhythmogenesis, abolition of DA synthesis was found to completely prevent flying in Drosophila (Pendleton et al. 2002).

Studies in vertebrate species such as the newt (Matsunaga et al. 2004), lamprey (Svensson et al. 2003) and zebrafish (Boehmler et al. 2007) have revealed the existence of a dopaminergic modulatory control of spinal locomotor-like activity. In vertebrate species, some CPG-activating effects have been reported. Dopamine and apomorphine (non-selective D1–D5 agonist) were found to display modulatory effects upon fictive locomotor activity in neonatal mice (Jiang et al. 1999; Whelan et al. 2000) and training-induced stepping in adult spinal cord-transected cats (Barbeau & Rossignol, 1991). Also in reduced models, non-physiological, high DA concentrations (millimolar range) were shown to activate CPGs although relatively slow rhythmic (0.05 Hz) activity compared to in vivo locomotion was reported (Kiehn & Kjaerulff, 1996; Barriere et al. 2004). Preliminary evidence of D1-mediated locomotor rhythmogenic effects in vivo was also recently reported following co-administration of D1 and 5-HT1A/7 receptor agonists in spinal cord-transected mice (Lapointe & Guertin, 2008).

The present study aimed at determining the potential existence of a role for DA receptor subtypes in vertebrate motor and locomotor rhythmogenesis. We hypothesized such a role to constitute a well-philogenetically conserved property that may be found also in vertebrate species and which expression and detection may be facilitated in in vivo conditions. To test this, we studied the effects on hindlimb movement elicited by a variety of brain-permeable DA receptor agonists administered intraperitoneally in low-thoracic (Th9/10) spinal cord-transected mice. Selective DA antagonists and knockout animals were also used to further dissect the contribution of each subtype of DA receptors to DA agonist-induced effects. This study is the first to assess and compare the effects of subclasses of DA agonists and antagonists on hindlimb motor/locomotor recovery after SCI. Preliminary results have been reported in abstract form (Lapointe & Guertin, 2005).

Methods

Animal and surgery

This work was performed in accordance with the Canadian Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and all procedures were approved by the Animal Research Committee of the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Quebec (CHUQ). Sixty-three mice (18 males + 45 females, 30–35 g) were used for the first series of experiments in wild-type CD1 mice (Charles River Laboratories, Montreal, QC, Canada). Another series of experiments using 62 mice either C57BL/6 wild-type (WT; N= 31, 25–30 g, 16 males and 15 females) or D5 knockout (D5KO with C57BL/6 background, 16 males and 15 females, N= 31, 25–30 g) mice was also performed. Animals were housed four or five per cage in a controlled-temperature environment maintained under a 12 h light–dark cycle with free access to food (Teklab global 18% protein rodent diet 2018, Harlan Teklab, Madison, WI, USA) and water. Pre-operative care included injections of lactate Ringer solution (1.0 ml, s.c.) and of an analgesic (buprenorphine; 0.1 mg kg−1, s.c.; Schering-Plough, Pointe-Claire, QC, Canada) 30 min prior to surgery. For surgery, mice were completely anaesthetized using isoflurane (2.5%) as described elsewhere (Guertin, 2005; Lapointe et al. 2006; Ung et al. 2007). In brief, the spinal cord transection (Tx) was performed inter-vertebrally using microscissors inserted between the 9th and 10th thoracic vertebrae. To ensure that complete transection was achieved, the inner vertebral walls were entirely scrapped with scissor tips in order to sever all remaining spinal fibres. The corresponding skin area was closed with clips and mice were placed for a few hours on a heating pad. Post-operative care included daily injections of lactate Ringer solution (2 × 1.0 ml, s.c.), buprenorphine (2 × 0.1 mg kg−1, s.c.), and Baytril (5 mg kg−1, s.c.; Bayer, Toronto, ON, Canada) for the 4 days. Bladders were also manually expressed twice a day until testing. Complete transections were confirmed behaviourally (flaccid paralysis of the hindlimbs for 1 week) and histologically (post mortem examination using luxol blue and cresyl violet coloration; Rouleau & Guertin, 2007).

Drug treatments

All tests were performed at 6 days post-Tx to allow reasonable time for animals to recover from surgery before behavioural testing. Six groups of CD1 mice (N= 7 per group) were used to assess the effects induced by each of the following DA receptor agonists (0.5–2.5 mg kg−1, i.p.): a D1-like agonist called cis-(±)-1-(aminomethyl)-3,4-dihydro-3-phenyl- 1H-2-benzopyran-5,6-diol hydrochloride also referred to as A-68930; a D1-like agonist called 6-chloro-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1-phenyl-1H-3-benzazepine hydrobromide also referred to as SKF-81297; a D2-like agonist called (4aR-trans)-4,4a,5,6,7,8,8a,9-octahydro-5-propyl- 1H-pyrazolo[3,4-g]quinoline hydrochloride referred to as quinpirole; a preferred D3 agonist (±)-7-hydroxy-2-dipropylaminotetralin hydrobromide referred to as 7-OH-DPAT; a preferred D4 agonist called N-(methyl-4-(2-cyanophenyl) piperazinyl-3-methylbenzamide maleate referred to as PD168077; and a non-selective DA agonist called (R)-5,6,6a,7-tetrahydro-6-methyl-4H-dibenzo[de,g]quinoline-10,11-diol hydrochloride referred to as apomorphine. Finally, two groups of C57BL/6 mice (9 wild-types and 9 D5 knockouts) were also tested with 0.5–2.5 mg kg−1 SKF-81297. Finally, three groups of mice (7 CD1, 9 C57BL/6 and 9 D5 KO) were instead previously pretreated with 1.0 mg kg−1 SCH23390 (a potent D1-like antagonist) 15 min prior to 0.5–2.5 mg kg−1 SKF-81297 administration.

All drugs listed above within the dose range chosen were shown to display central effects upon systemic delivery (Boulay et al. 1999; Clifford et al. 2001; Chausmer & Katz, 2002; Bernaerts & Tirelli, 2003; Chen et al. 2003; Iancu et al. 2005). The range of doses (e.g. 0.5–2.5 mg kg−1 SKF-81297) administered was equally divided within each group (e.g. in a group of 9 animals, 3 received 0.5 mg kg−1, 3 received 1.5 mg kg−1 and 3 other animals received 2.5 mg kg−1) in order to optimize intra-group detectability while reducing inter-group variability. Apomorphine was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA) whereas all other drugs were from Tocris (Ellisville, MO, USA). All agonists were diluted in sterile water except for SKF-81297, which was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and then diluted in sterile water to obtain a 2% solution (v/v) DMSO in water. Note that such low doses of DMSO had been shown not to affect hindlimb movement induction.

Breeding and identification of D5 knockout mice

Two couples of heterozygotes (D5−/+) were provided by Dr David Sibley from NINDS-NIH Bethesda, MD, USA (see Hollon et al. 1998 and Holmes et al. 2001 for generation and phenotyping identification details). From these couples, 31 D5−/− (knockouts) and 31 D5+/+ WT mice were generated using Southern blot genotyping for identification as follows: By the 21st day post-natal, tail ends (∼1 cm) were collected, kept on ice and then stored at −20°C until use. On the first day of the DNA extraction, pieces (0.5 cm) were ground up with a scalpel and put in RNA-free Eppendorf tubes. Lysis solutions (Tris 1 m, EDTA 0.5 m and SDS 20% (v/v) in RNA free bi-distilled water tris-EDTA (TE)) and proteinase K (20 mg ml−1) were added. Samples were vortexed and placed on a shaking platform at 55°C overnight (O/N). Addition of RNase A (10 mg ml−1) and incubation at 37°C for 45 min were performed. Acetate ammonium (7.5 m) was added and samples were vortexed prior to putting on ice for 10 min. Centrifugation at 13 000 g was performed for 3 min and the supernatant was delicately collected. DNA was washed with cold isopropanol and 70% ethanol (v/v) and re-hydrated in TE (pH 8) O/N at room temperature (RT). Following DNA sample dosage, PCR amplification was performed using Platinum Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen Canada Inc., Burlington, ON, USA) and two different primers to ease heterozygote and homozygote identification. The first primer (D1B1–D1B2-1, 630 bp) was used to amplify DNA from WT and D5−/+ mice whereas the second primer (D1B1–D1B3, 468 bp) was used to amplify DNA from D5−/+ and D5−/− mice (D1B1, ACTCTCTTAATCGTCTGGACCTTG; D1B2-1, GGAGGAGATACGGCGGATCTGAAC; D1B3, TGATCAACTAGTGCCCGGGCGGTA). PCR conditions consisted of an initial denaturation step (94°C for 1 min) followed by ligation (55°C for 2 min) and elongation phases (72°C for 2 min). Thirty more cycles (94°C for 45 s, 55°C for 1 min, 72°C for 1 min) followed by a final cycle (94°C for 1 min, at 55°C for 2 min and at 72°C for 10 min) were performed.

Assessment of drug-induced hindlimb movements

Hindlimb movements were assessed on a motor-driven treadmill moving at relatively low speed (8–10 cm s−1). A harness placed at the hip level was used to maintain animals in front of the camera (placed laterally). We were careful not to provide weight-support assistance with the harness or to use other forms of stimulation (e.g. tail or perineal pinching) during testing in order to avoid non-specific or variable effects. Hindlimb movements were monitored using a digital video-camera system (Sony DCR110, acquisition: 30 frames s−1, shutter speed: 1/4000) during 4 min immediately prior to and 15 min after drug injection. A semi-quantitative method (average combined score or ACOS) designed to assess hindlimb movements in Tx rodents was used (Guertin, 2005; Lapointe et al. 2006; Ung et al. 2007). The latter independently assessed the amplitude, incidence and frequency of non-locomotor and locomotor-like movement (NLM and LM, respectively). A NLM was defined as a unilateral (or non-bilaterally alternating) movement such as fast paw shaking, jerk, twitch or any other types of non-locomotor movements. In turn, a LM corresponded to a flexion followed by an extension (involving one or several articulations) or vice versa alternating in both hindlimbs (i.e. with an out-of-phase relationship). Arbitrary numerical values (either 1 for small or 2 for large) were attributed to assess movement amplitude. Movement incidence was defined as the number of mice displaying LM or NLM among all mice tested in that group. ACOS scores represented the sum of all the assessed values (see above): ACOS =[NLM min−1+ (LM min−1× 2)]× amplitude; see Guertin, 2005; Lapointe et al. 2006; Ung et al. 2007 for details and rationale.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Paired samples t tests were used to compare pre- vs post-injection data. One-way ANOVAs were performed to compare groups followed by a Tukey's post hoc test when significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 11.0 (Chicago, IL, USA). Results were expressed as mean ±s.e.m. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

D1/5 agonist-induced hindlimb movements

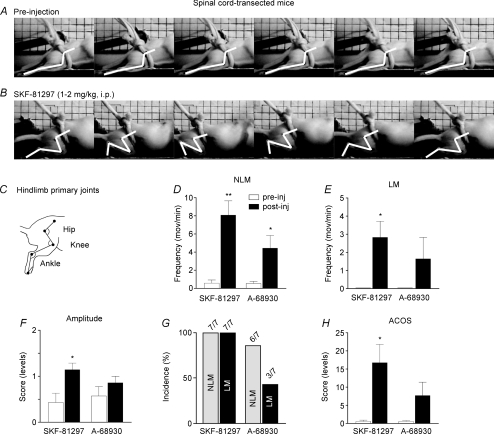

Intraperitoneal administration of D1/D5 agonists (0.5–2.5 mg kg−1) acutely elicited rhythmic movements in the previously immobilized hindlimbs of Tx mice. Figure 1 reveals with video-frames the type and extent of movements found following administration of SKF-81297, a D1/D5 receptor agonist. Prior to injection, no movements were found in that complete paraplegic animal placed on a motor-driven treadmill (Fig. 1A). In contrast, 15 min after drug injection, that same animal displayed clear bilateral flexion–extension movements (LM) resembling crawling (i.e. a typical cycle showed in Fig. 1B). Superimposed white sticks added to ease visualization clearly show that the effects were constituted of small-amplitude LMs (involving ankle and knee joints, see also Fig. 1C) with no weight-bearing. Averaged data from all mice tested report movement frequency, amplitude, incidence and corresponding ACOS values (Fig. 1D–H). NLM frequency (number min−1) significantly (P < 0.01) increased after SKF-81297 administration (8.07 ± 1.58) compared with pre-injection (0.57 ± 0.35, filled vs open bars, respectively Fig. 1D). Indeed, occasional spontaneous NLMs (< 1 movement min−1) can be found in non-treated chronic Tx mice (Guertin, 2005). On the other hand, LMs were also clearly induced by SKF-81297 since 2.82 ± 0.89 LMs min−1 were found after drug administration whereas absolutely no LMs were detected prior to drug administration (corresponding filled and open bars, respectively, Fig. 1E). Comparable effects were found with another D1/D5 agonist, A-68930 (Fig. 1D and E), although movement amplitude (assessed (for both NLM and LM simultaneously), shows significantly (P < 0.05) increased values after SKF-81297 (1.14 ± 0.14) but not A-68930 administration (0.86 ± 0.14, Fig. 1F). For reasons that are not clear, potent effects were induced only with SKF-81297 since LMs were found in all mice tested with SKF-81297 (Fig. 1G, 7/7) but only in some animals tested with A-68930 (i.e. 3/7 mice, Fig. 1G). Corresponding ACOS scores reveal that SKF-81297, and to a lesser extent A-68930 (just below statistical significance), clearly induced (P < 0.05) hindlimb movements in Tx mice (16.79 ± 5.00 and 7.71 ± 3.66, respectively) compared with pre-injection (0.54 ± 0.25) (filled vs open bars, Fig. 1H).

Figure 1. Effects of D1-like receptor agonists on hindlimb movement induction in CD1 mice.

Video images displaying a typical step cycle on a treadmill (or a 4 s bout of recording when no movement was found) prior to drug administration (A) and 15 min after 1–2 mg kg−1 SKF-81297 (B). Stick diagrams apposed on photographs were derived from three primary joints (i.e. hip, knee and ankle). Significant inductions of locomotor-like movements (LM, E; movements per minute (mov/min)), non-locomotor movements (NLM, D), movement amplitude (F), average combined scores (ACOS, H) and incidence (G) in paraplegic CD1 mice. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 compared with pre-injection.

Compared SKF-81297-induced movements in CD1 and C57BL/6 mice

Given the C57BL/6 background of the knockout animals used in this study (D5KO), we examined the effects induced by SKF-81297 in C57BL/6 wild-type animals. This was done also to assess potential strain-dependent effects (e.g. Lapointe et al. 2006).

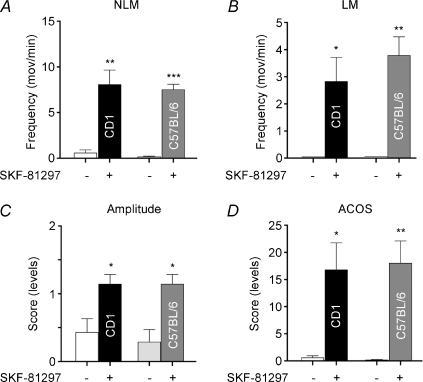

The number of NLM per minute increased significantly (P < 0.001) following SKF-81297 administration in C57BL/6 paraplegic mice (7.50 ± 0.61) compared with pre-injection (0.14 ± 0.09, grey vs open bars, respectively; Fig. 2A). As in CD1s (see also Fig. 1), a significant (P < 0.01) induction of LMs was also found in SKF-81297-treated C57BL/6 mice (3.79 ± 0.69; Fig. 2B). An identical increase (P < 0.05) of drug-induced movement amplitude values was found in C57BL/6 (1.14 ± 0.14) and CD1 (1.14 ± 0.14) animals (Fig. 2C). Corresponding ACOS scores were also largely (18.00 ± 4.11, P < 0.01) increased in C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 2D, grey bar).

Figure 2. SKF-81297-induced movements in CD1 and C57BL/6 mice.

Significant induction of NLMs (A), LMs (B), amplitude (C) and ACOS (D) following administration of 0.5–2.5 mg kg−1 SKF-81297 in paraplegic CD1 and C57BL/6 Tx mice. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 compared with pre-injection.

SKF-81297-induced movements in D5KO mice

Given that SKF-81297 binds to both the D1 and D5 receptor subtypes, we studied its effects in D5KO animals to assess specifically the role of the D1 receptor. We discovered that SKF-81297 induced comparable hindlimb movements in D5KOs as in wild-type paraplegic mice. This is shown in Fig. 3, where 6.06 ± 0.79 NLM min−1 were displayed following SKF-81297 in KO animals (Fig. 3A). We found also 2.44 ± 0.46 LM min−1 (P < 0.001) in SKF-81297-treated knockouts whereas movement amplitude (1.44 ± 0.18, P < 0.01) and ACOS score increases (16.2 ± 2.78, P < 0.001) resembled those found in wild-type animals (Fig. 3vsFig. 2). See also Fig. 4 where the results from wild-type and KO animals are shown side-by-side.

Figure 3. SKF-81297-induced movements in D5KO mice.

Significant induction of LMs, NLMs, amplitude (A) and ACOS (B) following administration of 0.5–2.5 mg kg−1 SKF-81297 in paraplegic D5KO mice. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 compared with pre-injection. Note that right end ordinate scales are used only for movement amplitude (A) and incidence (B) values.

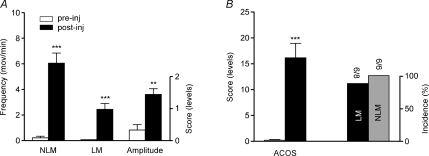

Figure 4. D1/D5 antagonist pretreated vs non-pretreated animals that received SKF-81297.

Significant reductions of NLMs (A), LMs (B), amplitude (C) and ACOS (D) following administration of 0.5–2.5 mg kg−1 SKF-81297 in CD1, C57BL/6 and D5−/− Tx mice previously pre-treated with 1.0 mg kg−1 SCH23390. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001.

D1/5 receptor antagonist-pretreated CD1, C57BL/6 and D5KO Tx mice

This series of experiments was performed to further dissect pharmacologically the role of D1 and D5 receptor subtypes. First, we tested, as a control, the effects of SCH23390 (D1/D5 receptor antagonist) administered separately in CD1, C57BL/6 or D5KO (open bars, Fig. 4). In all three groups (CD1, C57BL/6 and D5KO), no significant NLMs and LMs were found following administration of 1 mg kg−1 SCH23390 (Fig. 4A, B, E, F, I and J). Corresponding ACOS scores were near to zero (< 2 which corresponds to rare small-amplitude twitches as in non-treated animals; see Guertin, 2005; Lapointe et al. 2006; Ung et al. 2007).

Comparable effects were generally found following SKF-81297 administration in SCH23390-pretreated animals (grey bars, Fig. 4). Except for some increased NLMs (4.00 ± 0.95) found in D5KO animals, all groups and strains of mice displayed NLMs (< 3), LMs (none), movement amplitude (< 1) and ACOS values (< 4) that were non-significantly (P > 0.05) different in D1/5 antagonist-treated alone than D1/D5 antagonist-pretreated SKF-81297-treated animals (open vs grey bars, Fig. 4). In contrast, these graphs show that wild-type and KO animals that received only SKF-81297 displayed significantly (P < 0.01) increased NLM, LM and ACOS scores compared with the other groups (SCH23390 only or SCH23390 + SKF-81297). Only amplitude values (near ‘1’ which is considered as small movements) remain non-significantly (P > 0.05) changed between groups and conditions.

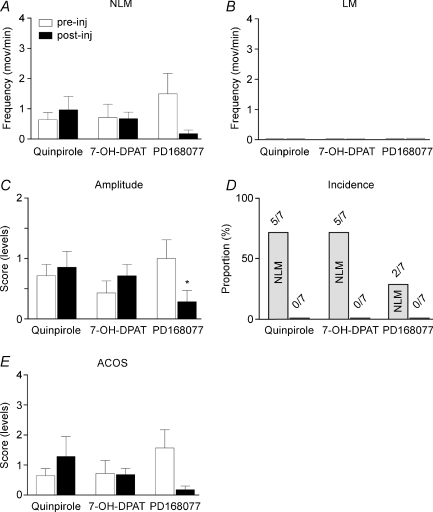

D2, D3 or D4 receptor agonist-induced movements

Additional experiment were performed in Tx animals using other types of agonists to investigate further the potential role of the D2, D3 or D4 receptor subtype in rhythmic movement generation. Overall, we found that activation of D2, D3 or D4 receptors did not induce significant hindlimb movements in Tx mice. Administration of quinpirole (0.5–2.5 mg kg−1, i.p.), a D2/D3 agonist, failed to significantly (P > 0.05) increase NLMs or to induce LMs (Fig. 5A–D). Correspondingly, ACOS scores did not significantly (P > 0.05) increase following quinpirole injection compared with pre-injection (Fig. 5E, filled vs open bars). Comparable results were found with 7-OH-DPAT (preferred D3 agonist; Levesque et al. 1992) or PD168077 (preferred D4 agonist; Glase et al. 1997). Both agonists failed to increase NLMs or to induce LMs in Tx mice as summarized by non-significantly (P > 0.05) changed ACOS scores (Fig. 5E).

Figure 5. D2, D3 and D4 receptor agonist-induced effects.

D2-like receptor agonists (i.e. quinpirole – D2/D3 preferred agonist, 7-OH-DPAT – preferred D3 agonist, and PD168077 – preferred D4 agonist) failed to significantly affect NLMs (A), LMs (B), movement amplitude (C), incidence (D) and ACOS (E) in paraplegic animals. *P < 0.05 compared with pre-injection.

Non-selective DA agonist-induced movements

Finally, we investigated the effects induced by non-selective D1–D5 receptor agonists such as apomorphine in order to examine whether D1-mediated effects remain if D2-like receptor are also activated. The results revealed that administration of 0.5–2.5 mg kg−1 apomorphine generally failed to increase NLMs or to induce LMs (Fig. 6A and B) as reflected also by the lack of significant (P > 0.05) ACOS increase post-injection vs pre-injection (Fig. 6B). Note that apomorphine induced some LMs in one mouse.

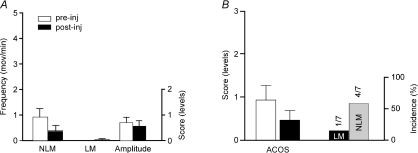

Figure 6. Effects of apomorphine on hindlimb movement induction.

Apomorphine failed to significantly change LMs, NLMs, amplitude (A) or ACOS and incidence (B). Note that right end ordinate scales are used only for movement amplitude (A) and incidence (B) values.

Statistically compared groups

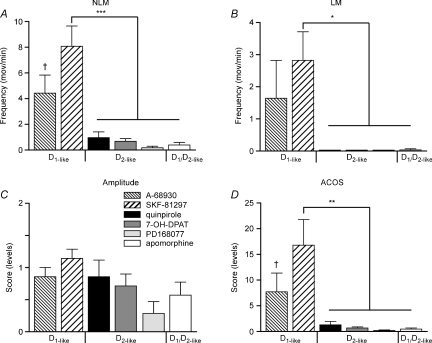

To properly compare results obtained with all these agonists, we performed statistical analyses between groups using post-injection values. Figure 7 clearly shows that compared with D1-like agonists (specifically SKF-81297), none of the D2-like (quinpirole, 7-OH-DPAT, PD168077) or D1/D2-like (apomorphine) agonists significantly increased NLMs or induced LMs in paraplegic CD1 mice (Fig. 7A and B). The analysis shows also that ACOS scores were severalfold (P < 0.01) lower in D2-like or D1/D2-like agonist-treated groups compared with SKF-81297-treated animals (Fig. 7D). In turn, although apparently higher movement amplitude values were found in D1 agonist-treated animals, differences between groups did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 7C).

Figure 7. Group comparisons.

Significant inductions of NLMs (A), LMs (B), movement amplitude (C) and ACOS (D) following administration of 0.5–2.5 mg kg−1 D1-like, D2-like or D1/D2-like agonists in Tx animals. †P < 0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001.

Discussion

One of the main findings is that among all types of DA agonists, only D1/D5 receptor agonists and specifically SKF-81297 acutely elicited rhythmic movements including LMs in untrained, non-assisted (no body-weight support assistance) and non-sensory stimulated (no tail pinching) adult mice completely spinal cord-transected (Th9/10). Moreover, SKF-81297-induced effects remained in D5KO but not in D1/D5 antagonist-pretreated animals (D5KO and wild-type), clearly suggesting specific D1 receptor-mediated effects.

This finding is supported in many ways by results from the literature. Firstly, the existence of dopaminergic projections from specific brain areas to all levels of the spinal cord has been well established (Bjorklund & Skagerberg, 1979; Hokfelt et al. 1979). Secondly, all subtypes of DA receptors, including the D1 subtype, are present in the mammalian spinal cord (e.g. rats, mice, cats and monkeys; see Ridet et al. 1992; Holstege et al. 1996; Zhu et al. 2007). Thirdly, although widely distributed in both the white and gray matters, stronger D1-like and D2-like receptor expression has been reported in the ventral horn and dorsal horn, respectively (Dubois et al. 1986; Fleetwood-Walker et al. 1988) which may suggest a specific role for D1-like receptors (either D1 or D5) in motor control. Fourthly, this wide distribution of immunolabelled D1 receptors is supported by a comparable pattern of mRNA expression recently shown in mice (Zhu et al. 2007), thus confirming in this study D1 expression at the protein level in the murine spinal cord.

On the other hand, DA has been found in the newt (Matsunaga et al. 2004), lamprey (Svensson et al. 2003) and zebrafish (Boehmler et al. 2007) to modulate locomotor-like rhythms induced by other means or compounds, but induced slow rhythms compared to in vivo locomotion in in vitro mouse models (Jiang et al. 1999; Whelan et al. 2000; Barriere et al. 2004).

Another reason why it has become possible here to demonstrate the existence of a role for DA in locomotor rhythm generation may be related to a contribution of endogenous glutamate release. This idea is strongly supported by results showing that 5-HT2 receptor agonist-induced LM critically depends upon endogenous NMDA receptor activation since AP5 completely blocks quipazine-induced air-stepping in Tx mice (Guertin, 2004). Moreover, this spontaneous endogenous release of glutamate found in vivo is somehow replaced in vitro by bath-applied NMDA as part of the cocktail (NMDA + 5-HT + DA) administered to potently trigger stable fictive locomotor activity in freshly prepared spinal cord isolated models (Jiang et al. 1999; Whelan et al. 2000).

It remains unclear as to why D1 but not D5 receptor activation was involved in mediating SKF-81297-induced effects. One explanation may reside in the fact that a close functional relationship has been shown to exist between NMDA and D1 receptors. DA potentiation of NMDA-induced responses (Cepeda et al. 1992, Cepeda et al1993; Levine et al. 1996a) was shown to involve specifically D1 receptors (Levine et al. 1996b). Actions involving several signalling cascades of second messengers were proposed as potential mechanisms for this potentiation. Also, co-immunoprecipitation experiments have revealed that D1 receptor c-terminus and NMDA receptor subunits are capable of direct structural interactions (Lee et al. 2002; Pei et al. 2004). Moreover, increased NMDA-mediated currents were reported after D1 receptor activation in vitro (Flores-Hernandez et al. 2002; Chen et al. 2004; Dunah et al. 2004). Altogether, these mechanisms may well have contributed to mediating SKF-81297-induced movements shown here given the contribution of endogenous glutamate release and NMDA receptor activation in Tx mice (Guertin, 2004).

The lack of large effects with apormophine (wide spectrum DA agonist) found in this study is somehow reminiscent of the results obtained also with the same compound in spinal cord-transected cats. Indeed, Barbeau & Rossignol (1991) had reported a lack of step-inducing effects with apomorphine in untrained paraplegic cats although modulating effects were found in late chronic animals that are capable of training-induced stepping. This lack of activating/inducing effects may perhaps be caused by (1) antagonizing effects mediated by D2 receptor activation or (2) greater binding affinity of apomorphine for D2 than D1 receptors as suggested elsewhere (Millan et al. 2002). In fact, D2-like receptor agonists have been shown to depress spinal cord activity (specifically the monosynaptic stretch reflex) in cats and rats (Carp & Anderson, 1982; Gajendiran et al. 1996). Along this line of evidence, it is generally believed that D1-like receptors stimulate whereas D2-like ones depress neuronal activity in the CNS (through opposing cyclic AMP actions; Bertran-Gonzalez et al. 2008).

It is important also to mention the surprising results found in D5KO animals following SKF-81297 and SCH23390 co-administration (Fig. 4I). While all other aspects of movement (LM, amplitude, ACOS) remained non-significantly changed in this group (Fig. 4J–L, grey bars compared with corresponding open and filled bars), NLM values (Fig. 4I, grey bar) were significantly (P < 0.05) increased in the D5KOs (but not in the wild-types, Fig. 4A and E) suggesting that SKF-81279 elicited some NLMs only in the D5KOs despite a block of D1 and D5 receptors with SCH23390. The reasons remain unclear, but it may be that an increased level of D1 expression has occurred as an adaptive mechanism in the D5KOs (as found sometimes in other KO models; see with 5-HTR1A in 5-HTR7KO, Landry et al. 2006) and that, in this condition, pretreatment with 1 mg kg−1 SCH23390 was insufficient to fully block (or entirely prevent) in D5KO mice all D1-mediated effects and specifically non-locomotor ones (NLM) following SKF-81297 administration.

Finally, providing further evidence of a role for DA in locomotor rhythmogenesis, DA release measured by direct methods in the rat lumbar cord was found to increase significantly during treadmill locomotion (Gerin et al. 1995; Gerin & Privat, 1998). This strongly suggests that the spinal dopaminergic system may play a role in mediating drug-induced locomotor-like movements in SCI subjects as well as normal locomotor behaviours in intact vertebrate species.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that D1/D5 receptors agonists can specifically elicit D1 receptor-mediated motor and locomotor-like rhythmic movements in completely low-thoracic-transected mice. However, in the absence of assistance or other forms of stimulation (e.g. tail pinching, training or weight support), D1 agonist-induced effects did include weight bearing or plantar foot placement (i.e. movements resembling crawling more than full stepping). This strongly supports the idea that incomplete CPG-activating effects were induced by D1-like receptor agonists which, in turn, may suggest that combinatorial approaches using other CPG-activating compounds also (Lapointe & Guertin, 2008) and/or sensory or electrical stimulation (Gerasimenko et al. 2007) could lead to full CPG activation and powerful locomotor movement induction in spinal cord-injured subjects.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the Fonds de Recherche en Sante du Quebec (FRSQ). N.P.L. and R.V.U. were supported by FRSQ.

References

- Barbeau H, Rossignol S. Initiation and modulation of the locomotor pattern in the adult chronic spinal cat by noradrenergic, serotonergic and dopaminergic drugs. Brain Res. 1991;546:250–260. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91489-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barriere G, Mellen N, Cazalets JR. Neuromodulation of the locomotor network by dopamine in the isolated spinal cord of newborn rat. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:1325–1335. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernaerts P, Tirelli E. Facilitatory effect of the dopamine D4 receptor agonist PD168,077 on memory consolidation of an inhibitory avoidance learned response in C57BL/6J mice. Behav Brain Res. 2003;142:41–52. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(02)00371-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertran-Gonzalez J, Bosch C, Maroteaux M, Matamales M, Herve D, Valjent E, Girault JA. Opposing patterns of signaling activation in dopamine D1 and D2 receptor-expressing striatal neurons in response to cocaine and haloperidol. J Neurosci. 2008;28:5671–5685. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1039-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorklund A, Skagerberg G. Evidence for a major spinal cord projection from the diencephalic A11 dopamine cell group in the rat using transmitter-specific fluorescent retrograde tracing. Brain Res. 1979;177:170–175. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90927-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehmler W, Carr T, Thisse C, Thisse B, Canfield VA, Levenson R. D4 dopamine receptor genes of zebrafish and effects of the antipsychotic clozapine on larval swimming behaviour. Genes Brain Behav. 2007;6:155–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2006.00243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulay D, Depoortere R, Perrault G, Borrelli E, Sanger DJ. Dopamine D2 receptor knock-out mice are insensitive to the hypolocomotor and hypothermic effects of dopamine D2/D3 receptor agonists. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:1389–1396. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carp JS, Anderson RJ. Dopamine receptor-mediated depression of spinal monosynaptic transmission. Brain Res. 1982;242:247–254. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90307-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cepeda C, Buchwald NA, Levine MS. Neuromodulatory actions of dopamine in the neostriatum are dependent upon the excitatory amino acid receptor subtypes activated. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:9576–9580. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cepeda C, Radisavljevic Z, Peacock W, Levine MS, Buchwald NA. Differential modulation by dopamine of responses evoked by excitatory amino acids in human cortex. Synapse. 1992;11:330–341. doi: 10.1002/syn.890110408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chausmer AL, Katz JL. Comparison of interactions of D1-like agonists, SKF 81297, SKF 82958 and A-77636, with cocaine: locomotor activity and drug discrimination studies in rodents. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;159:145–153. doi: 10.1007/s002130100896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Greengard P, Yan Z. Potentiation of NMDA receptor currents by dopamine D1 receptors in prefrontal cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:2596–2600. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308618100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JF, Moratalla R, Yu L, Martin AB, Xu K, Bastia E, Hackett E, Alberti I, Schwarzschild MA. Inactivation of adenosine A2A receptors selectively attenuates amphetamine-induced behavioral sensitization. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:1086–1095. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens S, Hochman S. Conversion of the modulatory actions of dopamine on spinal reflexes from depression to facilitation in D3 receptor knock-out mice. J Neurosci. 2004;24:11337–11345. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3698-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifford JJ, Kinsella A, Tighe O, Rubinstein M, Grandy DK, Low MJ, Croke DT, Waddington JL. Comparative, topographically-based evaluation of behavioural phenotype and specification of D1-like:D2 interactions in a line of incipient congenic mice with D2 dopamine receptor ‘knockout’. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25:527–536. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00246-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commissiong JW, Gentleman S, Neff NH. Spinal cord dopaminergic neurons: evidence for an uncrossed nigrospinal pathway. Neuropharmacology. 1979;18:565–568. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(79)90102-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois A, Savasta M, Curet O, Scatton B. Autoradiographic distribution of the D1 agonist [3H]SKF 38393, in the rat brain and spinal cord. Comparison with the distribution of D2 dopamine receptors. Neuroscience. 1986;19:125–137. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(86)90010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunah AW, Sirianni AC, Fienberg AA, Bastia E, Schwarzschild MA, Standaert DG. Dopamine D1-dependent trafficking of striatal N-methyl-D-aspartate glutamate receptors requires Fyn protein tyrosine kinase but not DARPP-32. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65:121–129. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleetwood-Walker SM, Hope PJ, Mitchell R. Antinociceptive actions of descending dopaminergic tracts on cat and rat dorsal horn somatosensory neurones. J Physiol. 1988;399:335–348. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Hernandez J, Cepeda C, Hernandez-Echeagaray E, Calvert CR, Jokel ES, Fienberg AA, Greengard P, Levine MS. Dopamine enhancement of NMDA currents in dissociated medium-sized striatal neurons: role of D1 receptors and DARPP-32. J Neurophysiol. 2002;88:3010–3020. doi: 10.1152/jn.00361.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gajendiran M, Seth P, Ganguly DK. Involvement of the presynaptic dopamine D2 receptor in the depression of spinal reflex by apomorphine. Neuroreport. 1996;7:513–516. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199601310-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerasimenko YP, Ichiyama RM, Lavrov IA, Courtine G, Cai L, Zhong H, Roy RR, Edgerton VR. Epidural spinal cord stimulation plus quipazine administration enable stepping in complete spinal adult rats. J Neurophysiol. 2007;98:2525–2536. doi: 10.1152/jn.00836.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerin C, Becquet D, Privat A. Direct evidence for the link between monoaminergic descending pathways and motor activity. I. A study with microdialysis probes implanted in the ventral funiculus of the spinal cord. Brain Res. 1995;704:191–201. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01111-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerin C, Privat A. Direct evidence for the link between monoaminergic descending pathways and motor activity: II. A study with microdialysis probes implanted in the ventral horn of the spinal cord. Brain Res. 1998;794:169–173. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00278-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glase SA, Akunne HC, Georgic LM, Heffner TG, MacKenzie RG, Manley PJ, Pugsley TA, Wise LD. Substituted [(4-phenylpiperazinyl)-methyl]benzamides: selective dopamine D4 agonists. J Med Chem. 1997;40:1771–1772. doi: 10.1021/jm970021c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girault JA, Greengard P. The neurobiology of dopamine signaling. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:641–644. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.5.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guertin PA. Role of NMDA receptor activation in serotonin agonist-induced air-stepping in paraplegic mice. Spinal Cord. 2004;42:185–190. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guertin PA. Semiquantitative assessment of hindlimb movement recovery without intervention in adult paraplegic mice. Spinal Cord. 2005;43:162–166. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris RM, Johnson BR, Peck JH, Kloppenburg P, Ayali A, Skarbinski J. Distributed effects of dopamine modulation in the crustacean pyloric network. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;860:155–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hokfelt T, Phillipson O, Goldstein M. Evidence for a dopaminergic pathway in the rat descending from the A11 cell group to the spinal cord. Acta Physiol Scand. 1979;107:393–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1979.tb06491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollon TR, Gleason TC, Grinberg A, Ariano MA, Huang SP, Drago J, Dreiling J, Crawley JN, Westphal H, Sibley DR. Generation of D5 dopamine receptor-deficient mice by gene targeting. Abstr Soc Neurosci. 1998;24:594. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes A, Hollon TR, Gleason TC, Liu Z, Dreiling J, Sibley DR, Crawley JN. Behavioral characterization of dopamine D5 receptor null mutant mice. Behav Neurosci. 2001;115:1129–1144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holstege JC, Van Dijken H, Buijs RM, Goedknegt H, Gosens T, Bongers CM. Distribution of dopamine immunoreactivity in the rat, cat and monkey spinal cord. J Comp Neurol. 1996;376:631–652. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19961223)376:4<631::AID-CNE10>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iancu R, Mohapel P, Brundin P, Paul G. Behavioral characterization of a unilateral 6-OHDA-lesion model of Parkinson's disease in mice. Behav Brain Res. 2005;162:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaber M, Robinson SW, Missale C, Caron MG. Dopamine receptors and brain function. Neuropharmacology. 1996;35:1503–1519. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(96)00100-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z, Carlin KP, Brownstone RM. An in vitro functionally mature mouse spinal cord preparation for the study of spinal motor networks. Brain Res. 1999;816:493–499. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)01199-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiehn O, Kjaerulff O. Spatiotemporal characteristics of 5-HT and dopamine-induced rhythmic hindlimb activity in the in vitro neonatal rat. J Neurophysiol. 1996;75:1472–1482. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.75.4.1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry ES, Rouillard C, Levesque D, Guertin PA. Profile of immediate early gene expression in the lumbar spinal cord of low-thoracic paraplegic mice. Behav Neurosci. 2006;120:1384–1388. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.120.6.1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapointe N, Guertin P. Specific dopamine receptor subtypes associated with hindlimb movement generation in early paraplegic mice. Soc Neurosci. 2005:516.10. Abstr. [Google Scholar]

- Lapointe NP, Guertin PA. Synergistic effects of D1/5 and 5-HT1A/7 receptor agonists on locomotor movement induction in complete spinal cord-transected mice. J Neurophysiol. 2008;100:160–168. doi: 10.1152/jn.90339.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapointe NP, Ung RV, Bergeron M, Cote M, Guertin PA. Strain-dependent recovery of spontaneous hindlimb movement in spinal cord transected mice (CD1, C57BL/6, BALB/c) Behav Neurosci. 2006;120:826–834. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.120.4.826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee FJ, Xue S, Pei L, Vukusic B, Chery N, Wang Y, Wang YT, Niznik HB, Yu XM, Liu F. Dual regulation of NMDA receptor functions by direct protein-protein interactions with the dopamine D1 receptor. Cell. 2002;111:219–230. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00962-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque D, Diaz J, Pilon C, Martres MP, Giros B, Souil E, Schott D, Morgat JL, Schwartz JC, Sokoloff P. Identification, characterization, and localization of the dopamine D3 receptor in rat brain using 7-[3H]hydroxy-N,N-di-n-propyl-2-aminotetralin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:8155–8159. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.17.8155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine MS, Li Z, Cepeda C, Cromwell HC, Altemus KL. Neuromodulatory actions of dopamine on synaptically-evoked neostriatal responses in slices. Synapse. 1996a;24:65–78. doi: 10.1002/syn.890240102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine MS, Altemus KL, Cepeda C, Cromwell HC, Crawford C, Ariano MA, Drago J, Sibley DR, Westphal H. Modulatory actions of dopamine on NMDA receptor-mediated responses are reduced in D1A-deficient mutant mice. J Neurosci. 1996b;16:5870–5882. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-18-05870.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga M, Ukena K, Baulieu EE, Tsutsui K. 7α-Hydroxypregnenolone acts as a neuronal activator to stimulate locomotor activity of breeding newts by means of the dopaminergic system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:17282–17287. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407176101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millan MJ, Maiofiss L, Cussac D, Audinot V, Boutin JA, Newman-Tancredi A. Differential actions of antiparkinson agents at multiple classes of monoaminergic receptor. I. A multivariate analysis of the binding profiles of 14 drugs at 21 native and cloned human receptor subtypes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;303:791–804. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.039867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missale C, Nash SR, Robinson SW, Jaber M, Caron MG. Dopamine receptors: from structure to function. Physiol Rev. 1998;78:189–225. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.1.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei L, Lee FJ, Moszczynska A, Vukusic B, Liu F. Regulation of dopamine D1 receptor function by physical interaction with the NMDA receptors. J Neurosci. 2004;24:1149–1158. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3922-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pendleton RG, Rasheed A, Sardina T, Tully T, Hillman R. Effects of tyrosine hydroxylase mutants on locomotor activity in Drosophila: a study in functional genomics. Behav Genet. 2002;32:89–94. doi: 10.1023/a:1015279221600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puhl JG, Mesce KA. Dopamine activates the motor pattern for crawling in the medicinal leech. J Neurosci. 2008;28:4192–4200. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0136-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridet JL, Sandillon F, Rajaofetra N, Geffard M, Privat A. Spinal dopaminergic system of the rat: light and electron microscopic study using an antiserum against dopamine, with particular emphasis on synaptic incidence. Brain Res. 1992;598:233–241. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90188-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouleau P, Guertin PA. Early changes in deep vein diameter and biochemical markers associated with thrombi formation after spinal cord injury in mice. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24:1406–1414. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.0260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skagerberg G, Lindvall O. Organization of diencephalic dopamine neurones projecting to the spinal cord in the rat. Brain Res. 1985;342:340–351. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)91134-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson E, Woolley J, Wikstrom M, Grillner S. Endogenous dopaminergic modulation of the lamprey spinal locomotor network. Brain Res. 2003;970:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)04216-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsyganov VV, Sakharov DA. Locomotor rhythms in the pond snail Lymnaea stagnalis: site of origin and neurotransmitter requirements. Acta Biol Hung. 2000;51:189–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ung RV, Lapointe NP, Tremblay C, Larouche A, Guertin PA. Spontaneous recovery of hindlimb movement in completely spinal cord transected mice: a comparison of assessment methods and conditions. Spinal Cord. 2007;45:367–379. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whelan P, Bonnot A, O'Donovan MJ. Properties of rhythmic activity generated by the isolated spinal cord of the neonatal mouse. J Neurophysiol. 2000;84:2821–2833. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.6.2821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang HW, Zhou LJ, Hu NW, Xin WJ, Liu XG. Activation of spinal d1/d5 receptors induces late-phase LTP of C-fiber-evoked field potentials in rat spinal dorsal horn. J Neurophysiol. 2005;94:961–967. doi: 10.1152/jn.01324.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, Clemens S, Sawchuk M, Hochman S. Expression and distribution of all dopamine receptor subtypes (D1-D5) in the mouse lumbar spinal cord: a real-time polymerase chain reaction and non-autoradiographic in situ hybridization study. Neuroscience. 2007;149:885–897. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.07.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, Clemens S, Sawchuk M, Hochman S. Unaltered D1, D2, D4, and D5 dopamine receptor mRNA expression and distribution in the spinal cord of the D3 receptor knockout mouse. J Comp Physiol A Neuroethol Sens Neural Behav Physiol. 2008;194:957–962. doi: 10.1007/s00359-008-0368-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]