Abstract

The pacemaker current, mediated by hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated (HCN) channels, contributes to the initiation and regulation of cardiac rhythm. Previous experiments creating HCN-based biological pacemakers in vivo found that an engineered HCN2/HCN1 chimeric channel (HCN212) resulted in significantly faster rates than HCN2, interrupted by 1–5 s pauses. To elucidate the mechanisms underlying the differences in HCN212 and HCN2 in vivo functionality as biological pacemakers, we studied newborn rat ventricular myocytes over-expressing either HCN2 or HCN212 channels. The HCN2- and HCN212-over-expressing myocytes manifest similar voltage dependence, current density and sensitivity to saturating cAMP concentrations, but HCN212 has faster activation/deactivation kinetics. Compared with HCN2, myocytes expressing HCN212 exhibit a faster spontaneous rate and greater incidence of irregular rhythms (i.e. periods of rapid spontaneous rate followed by pauses). To explore these rhythm differences further, we imposed consecutive pacing and found that activation kinetics of the two channels are slower at faster pacing frequencies. As a result, time-dependent HCN current flowing during diastole decreases for both constructs during a train of stimuli at a rapid frequency, with the effect more pronounced for HCN2. In addition, the slower deactivation kinetics of HCN2 contributes to more pronounced instantaneous current at a slower frequency. As a result of the frequency dependence of both instantaneous and time-dependent current, HCN2 exhibits more robust negative feedback than HCN212, contributing to the maintenance of a stable pacing rhythm. These results illustrate the benefit of screening HCN constructs in spontaneously active myocyte cultures and may provide the basis for future optimization of HCN-based biological pacemakers.

The pacemaker current (If) plays a major role in the initiation and regulation of cardiac rhythm due to its activation upon hyperpolarization and modulation by direct binding of cAMP (DiFrancesco, 1993). The molecular correlates of If are the hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated (HCN) channels (Biel et al. 1999; Santoro & Tibbs, 1999; Accili et al. 2002). There are four HCN isoforms (HCN1–4) in mammals, and three of these are present in heart. HCN1 shows the fastest kinetics but low sensitivity to intracellular cAMP. Both HCN2 and HCN4 respond strongly to cAMP, but HCN4 has slower kinetics. Recently, HCN-based biological pacemakers have been reported (Qu et al. 2003; Plotnikov et al. 2004, 2008; Xue et al. 2005; Bucchi et al. 2006; Lieu et al. 2008). Because of HCN2's strong cAMP response and moderate kinetics, our group has focused on this isoform as the backbone of a biological pacemaker and has made mutant and chimeric channels in an attempt to optimize HCN2-based biological pacemakers (Bucchi et al. 2006; Plotnikov et al. 2008).

A major focus has been the chimeric channel, HCN212, which incorporates the pore-forming portion of HCN1 and the amino- and carboxy-termini of HCN2. This chimeric channel combines the fast activation kinetics of HCN1 and the more robust cAMP response of HCN2 (Wang et al. 2001). However, HCN212 manifested pacemaker rates in vivo that are too rapid to be desirable and these were interspersed with excessively long pauses. Therefore we embarked on a systematic study to explore which biophysical properties contribute to the difference between HCN2 and HCN212 channels with respect to cardiac pacing.

HCN channels incorporate a slowly time-dependent component (IHCN) and an instantaneous current (Iins) (Proenza et al. 2002; Proenza & Yellen, 2006). Iins can be enhanced by incomplete deactivation and strongly depends on the frequency of hyperpolarizing pulses (Mistrik et al. 2006). In addition, it has been reported that the voltage dependence of HCN channels exhibits hysteresis under non-equilibrium conditions (Azene et al. 2005), and recent allosteric models provide a theoretical framework for this behaviour (DiFrancesco, 1999; Altomare et al. 2001; Wang et al. 2002). During cardiac activity the membrane potential of the myocyte changes dynamically and always is in a non-equilibrium state. Thus, contributions of both the instantaneous and time-dependent components of If to diastole should vary with pacing frequency. We hypothesized that the frequency dependence of HCN2 and HCN212 might differ, contributing to their distinct functionality as biological pacemakers in vivo. We therefore have explored both the equilibrium and non-equilibrium characteristics of HCN2 and HCN212 currents. Further, we conducted these studies in newborn rat ventricular myocytes to provide a cardiac context, because the expression system can affect the functional characteristics of expressed channels (Qu et al. 2002). This also allowed us to study the effect of these constructs on spontaneous activity.

Methods

Ethical approval

Animal handling procedures were reviewed and approved by the local Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Columbia University Medical Center, and conform to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Institutes of Health publication No. 85-23, revised 1996).

Cell culture

Newborn rat ventricular myocyte cultures were prepared as previously described (Protas & Robinson, 1999). Briefly, 1- to 2-day-old Wistar rats (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA, USA) were killed by decapitation and ventricles were dissociated using a standard trypsinization procedure. Myocytes were harvested and incubated in serum-free medium at 37°C, 5% CO2. Action potential studies were conducted on 4 to 6 day monolayer cultures plated directly onto fibronectin-coated 9 mm × 22 mm glass coverslips. For electrophysiology experiments, the cell monolayer was briefly (1–2 min) exposed to 0.1% trypsin, and cells were replated onto fibronectin-coated coverslips at low density, and then studied 2–6 h later.

Adenoviral constructs and expression

Both mHCN2 and mHCN212 were packaged in the pDC515 shuttle vector (AdMax, Microbix Biosystems, Inc., Toronto, Ontario, Canada), then cotransfected with pBHGfrtΔE1, 3FLP vector (AdMax) into E1-complementing HEK 293 cells. Successful recombination of the shuttle plasmid and adenoviral genomic vector resulted in production of the appropriate adenovirus, which was expressed and studied in newborn rat ventricular myocytes as described previously (Qu et al. 2001). Since we find that > 90% of cells exposed to an HCN adenovirus (multiplicity of infection 20) in vitro express pacemaker currents, we did not co-infect with green fluorescent protein (GFP)-expressing adenovirus to identify expressing cells. However, we employed a GFP-expressing adenovirus as our control.

Electrophysiology

The whole-cell patch clamp technique was used to measure HCN currents from newborn rat ventricular myocytes as previously described (Qu et al. 2001). Data were acquired at 10 kHz using an Axopatch 200B amplifier and pCLAMP 9 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Voltage clamp data were analysed off-line using Clampfit 9 (Molecular Devices) and Origin 7 (Origin Lab Corp., Northampton, MA, USA). All recordings were obtained at 35°C. The standard external solution contained (in mmol l−1): NaCl, 140; NaOH, 2.3; MgCl2, 1; KCl, 10; CaCl2, 1; Hepes, 5; glucose, 10; pH 7.4. MnCl2 (2 mmol l−1) and BaCl2 (2 mmol l−1) were added to block other currents during whole-cell patch clamp recording. For action potential recording the blockers were omitted and KCl reduced to 5.4 mmol l−1. The pipette solution contained (in mmol l−1): aspartic acid, 130; KOH, 146; NaCl, 10; CaCl2, 2; EGTA-KOH, 5; Mg-ATP, 2; Hepes-KOH, 10; pH 7.2. The pipette resistance was typically 2–3 MΩ. Current densities were normalized to cell membrane capacitance. Records were not corrected for liquid junction potential, which was previously determined to be 9.8 mV under these recording conditions.

Action potential (AP) recordings were done in whole-cell mode on a monolayer culture. Action potential parameters were measured on four successive APs and averaged to determine the values for each culture plate. We measured maximum diastolic potential (MDP), take-off potential (TOP) and early diastolic depolarization (EDD), all as previously described (Bucchi et al. 2007). Spontaneous rate was determined as the reciprocal of the average cycle length over a 2 s period.

Whole-cell currents were evoked with the following protocols. Protocol 1: To measure the HCN activation relation and activation time constant, hyperpolarizing steps from −25 to −125 mV were applied from a holding potential of −25 mV, followed by a tail current step to −85 mV. The duration of test steps was 3 s. Protocol 2: To measure HCN deactivation, currents were recorded for 5 s with a family of test voltages ranging from −80 to +20 mV preceded by a 1 s prepulse to −120 mV. Protocol 3: We performed an envelope test to illustrate the effect of interpulse interval on HCN channels for a voltage corresponding to typical action potential overshoot. The membrane was stepped from the −30 mV holding potential to −80 mV for 4 s, and then stepped to +20 mV for a variable time interval, after which it was returned to −80 mV for 4 s. Test pulses were repeated every 12 s. Protocol 4: To analyse the effect of the length of a hyperpolarizing prepulse on the activation kinetics of HCN channels, the membrane was stepped from the −30 mV holding potential to −80 mV for different durations and then returned to +20 mV for 150 ms (to approximate typical action potential duration) and stepped again to −80 mV for 6 s. Test pulses were repeated every 12 s. Protocol 5: To explore the effect of consecutive stimuli on HCN channels, a train of square pulses was used to mimic action potentials. The holding potential was −80 mV for a duration long enough (4–6 s) to achieve equilibrium. Subsequently, two protocols were performed by consecutively stepping to +20 mV for 150 ms followed by a step to −80 mV for 150 or 1850 ms to mimic cycle lengths of 300 and 2000 ms, respectively. To minimize the effect of current rundown or drift, the order of the two protocols was alternated in successive cells.

For activation curves, the normalized plot of tail current versus test voltage was fitted to a Boltzmann equation:

in which A1 is the offset of the holding current, A2 is the maximal tail current amplitude, V is the voltage during the hyperpolarizing test pulse,  is the midpoint potential of activation, and s is the slope factor. The normalized data were averaged among different experiments and refitted to the Boltzmann equation with A1= 0 and A2= 1. Kinetics of activation (τact) were determined from the same tracings by a single exponential fit to the early time course of the current activated by hyperpolarization. The initial delay and any late slow activation were ignored. Kinetics of deactivation (τdeact) were determined by a single-exponential fit of the time course of the current trace at each test voltage after activation by a prepulse to −120 mV. For estimating open and close rates, the bell-shaped distribution of averaged τact and τdeact was fitted to:

is the midpoint potential of activation, and s is the slope factor. The normalized data were averaged among different experiments and refitted to the Boltzmann equation with A1= 0 and A2= 1. Kinetics of activation (τact) were determined from the same tracings by a single exponential fit to the early time course of the current activated by hyperpolarization. The initial delay and any late slow activation were ignored. Kinetics of deactivation (τdeact) were determined by a single-exponential fit of the time course of the current trace at each test voltage after activation by a prepulse to −120 mV. For estimating open and close rates, the bell-shaped distribution of averaged τact and τdeact was fitted to:

where α and β reflect the open and close rates at zero voltage, respectively, Vt is the test voltage, and V0 is the voltage at which the rate constants change by e-fold. To obtain information about the biological behaviour of HCN channels under consecutive stimuli, we measured the total Iins and the magnitude of the time-dependent HCN current at the 150 ms time point (IHCN,150 ms). This reflects current that would flow during early diastole.

Computer simulation

We employed the sinoatrial node (SAN) model of Kurata et al. (2002), and fitted models to the experimentally measured activation/deactivation kinetics of expressed HCN2 and HCN212 in the myocyte cultures (see Table 1 and Fig. S1 in the online Supplemental material). The midpoint and slope of the activation curve were also modified to match the experimental data. Since the maximum conductance of pacemaker current in the model was comparable to that of both HCN2 and HCN212 in the cultures, we did not modify that parameter.

Statistical analysis

Pooled data are presented as mean ±s.e.m.; n denotes the number of cells. To minimize the effect of culture-to-culture variability, for each culture cells were prepared expressing each construct and data from at least three separate cultures were pooled for each comparison. Student's paired t test or Fisher's exact test was performed for comparison between two groups, as appropriate. An ANOVA was performed for multiple comparison, followed by a modified t test with Bonferroni correction (SigmaStat, Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). Values of P < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Biophysical properties of HCN2 and HCN212 currents expressed in newborn rat ventricular myocytes

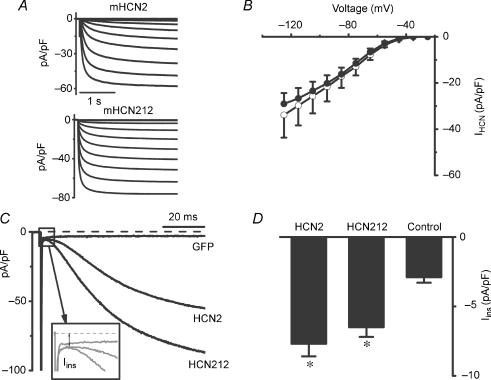

Because the expression level of HCN channels can influence the effect on cardiac pacing (Bucchi et al. 2006), we first compared the expression efficiency of HCN2 and HCN212 channels in myocytes. There was no difference in cell capacitance between HCN2- and HCN212-expressing myocytes (30.0 ± 2.2 pF, n = 26, and 33.0 ± 3.2 pF, n = 22, respectively; P > 0.05). In whole-cell voltage clamp experiments, both HCN2- and HCN212-expressing myocytes gave rise to robust inward currents in response to hyperpolarizing voltages. The HCN212 chimeric channels were well expressed in newborn rat ventricular myocytes, similar to our findings for HCN2 channels (Qu et al. 2001). The percentage of myocytes expressing HCN212 current was not significantly different from that of myocytes expressing HCN2 current (91% and 93% for HCN2 and HCN212, defined as percentage of cells with pacemaker current > 200 pA at −115 mV; n = 33 and 27, respectively). Representative normalized current traces are shown in Fig. 1A. For IHCN, the current density in the two groups at any voltage was not different (Fig. 1B). For example, mean current densities of IHCN2 and IHCN212 at −125 mV were 29.0 ± 4.5 pA pF−1 (n = 8) and 33.9 ± 9.8 pA pF−1 (n = 12, P > 0.05), respectively. We also examined the magnitude of the instantaneous current (Iins) of HCN channels, defined as the difference between the zero current level and the initial current following a voltage step. Since we were interested in differences in this component between constructs (and as a function of frequency, as described below), rather than absolute value, we did not conduct experiments to measure and subtract leak current from these records. As shown in Fig. 1C and D, the mean current densities of Iins,HCN2 and Iins,HCN212 using a single step from −30 mV to −120 mV were 8.2 ± 1.0 pA pF−1 (n = 15) and 6.8 ± 0.7 pA pF−1 (n = 13, P > 0.05), respectively, and both values were larger than that in GFP-expressing myocytes (3.7 ± 0.6 pA pF−1, n = 17, P < 0.001). These observations indicate that HCN2 and HCN212 channel expression is comparable in newborn rat ventricular myocytes and that, under these recording conditions, the two constructs produce equivalent instantaneous and steady-state time-dependent current.

Figure 1. Expression of HCN2 and HCN212 in newborn rat ventricular myocytes.

A, representative whole-cell current tracings of myocytes expressing HCN2 (top) and HCN212 (bottom) channels. Currents were evoked by stepping from a holding potential of −25 mV to different hyperpolarizing voltage steps ranging from −25 to −125 mV in 10 mV increments. B, the mean I –V relationship of HCN2 (n = 8, filled circles) and HCN212 (n = 12, open circles). The HCN current (IHCN) is defined as the time-dependent component at the end of the 3 s test pulse. C, representative instantaneous current Iins, HCN2, Iins,HCN212 and Iins,GFP recorded at a single hyperpolarizing step (−120 mV) from a holding potential of −30 mV. The inset shows how the instantaneous component was measured; it is defined as the difference between the zero current level and the initial current level where the time-dependent current component begins, and includes leak current. D, the instantaneous current density in response to voltage steps to −120 mV in myocytes over-expressing HCN2 (n = 15), HCN212 (n = 13), GFP (n = 17). *P < 0.05 versus GFP.

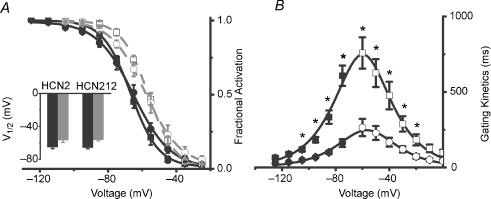

We further analysed the voltage dependence of HCN2 and HCN212 channels heterologously expressed in myocytes under equilibrium recording conditions. HCN2 and HCN212 channels exhibited similar voltage dependence of activation as shown in Fig. 2A. The mean  was −65.9 ± 1.4 mV (n = 8) for HCN2 versus −65.2 ± 1.9 mV (n = 10) for HCN212 (P > 0.05). The corresponding s values were 8.2 ± 0.9 mV and 10.7 ± 1.1 mV respectively (P > 0.05). The similar voltage dependence of HCN2 and HCN212 in newborn myocytes is consistent with data obtained previously in adult myocytes (Plotnikov et al. 2008).

was −65.9 ± 1.4 mV (n = 8) for HCN2 versus −65.2 ± 1.9 mV (n = 10) for HCN212 (P > 0.05). The corresponding s values were 8.2 ± 0.9 mV and 10.7 ± 1.1 mV respectively (P > 0.05). The similar voltage dependence of HCN2 and HCN212 in newborn myocytes is consistent with data obtained previously in adult myocytes (Plotnikov et al. 2008).

Figure 2. Steady-state properties of HCN2 and HCN212 in newborn rat ventricular myocytes.

A, the mean activation–voltage relation of HCN2 and HCN212 in the absence and presence of cAMP. Mean fractional activation curves of HCN2 (squares) and HCN212 (circles) obtained in the absence (black symbols) and in the presence (grey symbols) of 10 μmol l−1 cAMP in the pipette solution. For illustrative purposes, the mean data were fitted to the Boltzmann equation for experiments in the absence (continuous black lines) and in the presence (dashed grey lines) of cAMP. Inset: mean  values without (black) and with (grey) cAMP. B, voltage dependence of activation (filled symbols) and deactivation (open symbols) time constants of HCN2 (squares) and HCN212 (circles). Mean activation values were obtained from 10 cells for both HCN2 and HCN212; mean deactivation time constant values were obtained from 7 and 6 cells for HCN2 and HCN212, respectively. The curves are the fits to the equation

values without (black) and with (grey) cAMP. B, voltage dependence of activation (filled symbols) and deactivation (open symbols) time constants of HCN2 (squares) and HCN212 (circles). Mean activation values were obtained from 10 cells for both HCN2 and HCN212; mean deactivation time constant values were obtained from 7 and 6 cells for HCN2 and HCN212, respectively. The curves are the fits to the equation  . *Voltages differ by multiple comparison (P < 0.05).

. *Voltages differ by multiple comparison (P < 0.05).

An important criterion of an HCN gene-based biological pacemaker is better autonomic responsiveness, resulting from direct binding of cAMP to HCN channels (Bucchi et al. 2006; Robinson et al. 2006). To test whether HCN2 and HCN212 expressed in myocytes exhibited similar cAMP responsiveness, the activation curves were further investigated in the presence of saturating cAMP in the pipette solution (10 μmol l−1). Both channels responded equally to the presence of saturating intracellular cAMP. In the presence of cAMP, calculated values were  and s = 7.8 ± 0.6 mV for HCN2 (n = 6);

and s = 7.8 ± 0.6 mV for HCN2 (n = 6);  and s = 9.9 ± 1.1 mV for HCN212 (n = 7), respectively. For HCN2 and HCN212, control and cAMP relations differ significantly (a 9.5 mV and 8.3 mV shift, respectively). HCN2 and HCN212 curves do not differ from each other under either control conditions or in the presence of cAMP (P > 0.05).

and s = 9.9 ± 1.1 mV for HCN212 (n = 7), respectively. For HCN2 and HCN212, control and cAMP relations differ significantly (a 9.5 mV and 8.3 mV shift, respectively). HCN2 and HCN212 curves do not differ from each other under either control conditions or in the presence of cAMP (P > 0.05).

We next analysed the gating kinetics of HCN channels in myocytes. The representative currents demonstrated that HCN212 channels exhibit faster activation kinetics than HCN2 (Fig. 1A). In addition, when membrane potential was depolarized after stepping to −120 mV to fully activate HCN212 channels, the deactivation kinetics of HCN212 channels were also faster. The complete relationship between gating kinetics (both activation and deactivation) and membrane potential is illustrated in Fig. 2B for HCN212 and HCN2. Plotting these time constants together against the test potential revealed that the voltage dependence of τact and τdeact had a bell-shaped form. α and β derived from this curve were: 1.2 × 10−4 and 0.03498 for HCN212; 3 × 10−5 and 0.01598 for HCN2. Analysis of gating kinetics indicate that the mean activation and deactivation time constants of HCN212 channels are faster than those of HCN2 channels over most of the voltage range analysed, and the relative peaks of the kinetics–voltage relationships are consistent with the previously determined  values.

values.

Thus, under equilibrium conditions HCN2 and HCN212 channels expressed in newborn rat ventricular myocytes have equivalent voltage dependence, current amplitude and responsiveness to saturating cAMP, but HCN212 exhibits faster activation and deactivation kinetics.

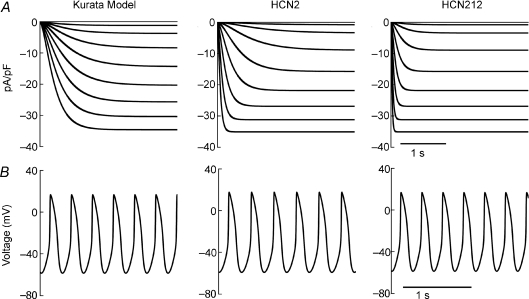

Computer simulation of effect of HCN kinetics on automaticity

To investigate the possible impact of the difference in activation and deactivation kinetics on spontaneous rate, we utilized the Kurata computer model of the SAN (Kurata et al. 2002). Supplemental Fig. S1 shows the voltage dependence of activation gating (panel A) and activation/deactivation time constants (panel B) in the original SAN model and after modification to match experimental data in myocytes expressing HCN2 or HCN212 (as shown in Fig. 2). Compared to If in the original SAN model, expressed HCN2 activation kinetics are faster at negative potentials, but at less negative potentials within the diastolic potential range, activation kinetics are slower in HCN2 channels. In addition, deactivation kinetics are slower at all voltages. HCN212 has faster activation kinetics than SAN If at all voltages, while at potentials positive to −40 mV the deactivation kinetics of HCN212 and SAN If are comparable.

The resulting families of simulated currents in each case are shown in Fig. 3A. Conductance was the same in all three simulations, and the current magnitude for HCN2 and HCN212 in the simulation match the mean experimental values (Fig. 1B). Simulated spontaneous action potentials are shown in Fig. 3B. Using the HCN2 experimental data, the cycle length was longer than that of the SAN model (329 versus 308 ms), reflecting a slower rate as a result of the slower activation kinetics at diastolic potentials. When the HCN2 parameters are replaced by those of HCN212, cycle length shortens (from 329 to 305 ms). To determine if this was entirely due to the faster activation, we also undertook a simulation where we changed only the activation kinetics to match the HCN212 data, leaving deactivation and all other parameters unchanged. In this case cycle length was also shorter than in the pure HCN2 simulation (318 ms), but not as short as in the full HCN212 simulation. Thus both activation and deactivation kinetics can impact spontaneous rate.

Figure 3. Simulated whole-cell current tracing and simulated spontaneous action potentials in the Kurata sinoatrial node (SAN) model with original Kurata If, HCN2 expression and HCN212 expression.

A, currents were evoked by stepping from a holding potential of −25 mV to different hyperpolarizing voltage steps ranging from −25 to −125 mV in 10 mV increments. B, spontaneous action potentials were simulated with each of the pacemaker current configurations – the SAN model with unchanged If (Kurata et al. 2002) is shown on the left, HCN2 in the middle, and HCN212 on the right.

The effect of HCN2 and HCN212 expression on spontaneous beating of newborn myocytes

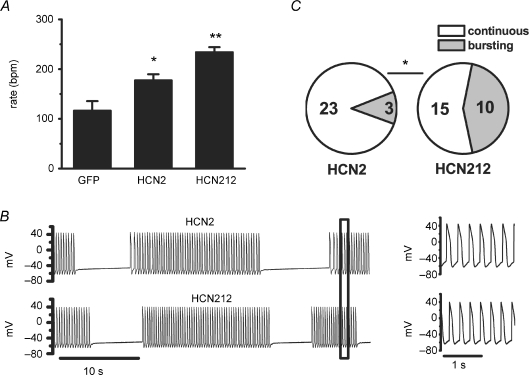

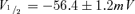

The computer simulations lend validation to the hypothesis that changes to channel kinetics can result in changes in spontaneous rate. We therefore next explored the effect of the two HCN constructs on spontaneous activity of monolayer cultures of newborn rat ventricular myocytes. Spontaneous action potentials (APs) were recorded from a myocyte within the monolayer using a whole-cell patch electrode. As expected from the faster activation kinetics with comparable expression efficiency, and the computer simulation, HCN212 resulted in a faster spontaneous rate than HCN2 channels (234 ± 10 beats min−1, n = 25, and 177 ± 12 beats min−1, n = 26, respectively, P < 0.05), and both groups beat faster than did control cultures expressing GFP (116 ± 19 beats min−1, n = 7, P < 0.05, Fig. 4A).

Figure 4. Effects of HCN2 and HCN212 channel expression on spontaneous activity of newborn rat ventricular myocytes.

A, mean spontaneous beat rate of myocytes expressing GFP, HCN2 and HCN212. *P < 0.05 versus GFP; **P < 0.05 versus HCN2 and GFP. B, representative examples of spontaneous action potentials with bursting behaviour recorded from an HCN2-expressing (top) and HCN212-expressing culture (bottom). At the far right, the portion of each trace indicated by the box is displayed on an expanded time scale. C, the incidence of bursting behaviour in HCN-expressing monolayers. *P < 0.05 versus HCN212.

However, the incidence of bursting behaviour in HCN212-expressing monolayers was significantly greater than that in HCN2 cultures; 40% (10 out of 25) and 11.5% (3 out of 26 cells, P < 0.05, Fig. 4B and C), respectively. In both groups, the rate within the burst was statistically not different from the rate observed in non-bursting cultures (HCN212: 228 ± 16 versus 238 ± 19, P > 0.05; HCN2: 147 ± 24 versus 181 ± 13, P > 0.05, respectively).

We considered that the difference in rhythmicity could be secondary to the effects of one of the constructs on other ionic currents. We first explored this by measuring action potential parameters in each case. The HCN2 and HCN212 cultures (n = 25 each) did not differ with respect to action potential amplitude (94.74 ± 2.24 and 96.76 ± 2.24 mV, respectively; P > 0.05), MDP (−58.76 ± 1.19 and −59.55 ± 1.33 mV, respectively; P > 0.05) or TOP (−51.38 ± 1.32 and −49.31 ± 1.62 mV; P > 0.05), but EDD was significantly greater with HCN212 expression, consistent with the higher rate (0.06 ± 0.01 and 0.14 ± 0.01 V s−1, respectively; P < 0.05). Regression analysis indicated that any differences in action potential duration were secondary to differences in rate (Supplemental Fig. S2). We also investigated other currents that could contribute to excitability and/or automaticity. We measured the inward rectifier current, defined as the current blocked by 1 mm Ba2+. These experiments were done in the presence of 3 × 10−6 mol l−1 ivabradine (Servier Laboratories, Courbevoie, France) to minimize any possible contamination from the large HCN currents. At −80 mV the current magnitudes were 89 ± 19 and 107 ± 22 pA (n = 7–8; P > 0.05) for HCN2 and HCN212, respectively. We also measured inward Na+ current, and found no difference in the peak current, the I –V relation, or the inactivation relation in HCN2- and HCN212-expressing cultures (Supplemental Fig. S3). Finally, we performed Western blot analysis to determine protein expression in HCN2 versus HCN212 cultures of Na+ channels (using a pan-Na+ antibody) and the Kir2.1 component of the inward rectifier; expression was comparable in both cases (Supplemental Fig. S4A). We did find HCN212 expression was greater than that of HCN2; however, when the light sarcolemmal membrane fraction was analysed separately expression was equivalent (Supplemental Fig. S4B).

Thus, neither the difference in spontaneous rate nor the irregularity of rhythm observed with HCN212 can readily be ascribed to secondary effects of one construct on other ionic currents. While the computer simulation suggests that the faster rate can be explained by the altered kinetics, it should be noted that the observation of irregular rhythms with HCN212 was not observed in the simulation, which is based on a Hodgkin–Huxley formulism of the pacemaker channel. Such a model does not replicate the non-equilibrium behaviour of the channel, which requires more complex allosteric modelling. This therefore led us to experimentally explore the non-equilibrium behaviour of the two constructs in greater detail.

Modulation of HCN channels under non-equilibrium conditions

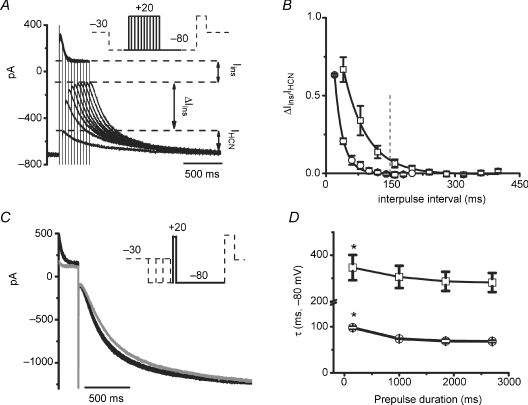

At faster spontaneous rates, myocytes spend more time in a depolarized state. To explore the impact of this on both the instantaneous and time-dependent component of HCN current, we imposed two different double hyperpolarizing protocols. First, we performed protocol 3 (an envelope test, see Methods) with varying interpulse intervals for a step to +20 mV. This was intended to illustrate the effect of AP duration (APD; mimicked with a square pulse to +20 mV of varying duration) on residual Iins. Representative tracings of HCN2 evoked by the protocol are shown in Fig. 5A. As expected, there is a reciprocal relation between the instantaneous and time-dependent components of the current, with the time-dependent component of HCN current (IHCN) becoming smaller as the interpulse interval decreases. The corresponding enhancement of Iins (ΔIins) reflects residual current from incomplete deactivation of HCN channels as a result of the short time at depolarized potentials (Proenza & Yellen, 2006). Plotting ΔIins against the interpulse interval (Fig. 5B) yields the average time course of current deactivation for the test pulse of +20 mV. An exponential fit to these data yields time constants of 52.8 ± 8.3 ms (n = 4) and 21.7 ± 3.3 ms (n = 3) for ΔIins,HCN2 and ΔIins,HCN212, respectively (P < 0.01). As illustrated by the dashed vertical line at 150 ms, for HCN2 the increase in instantaneous current equals 8.4% of the time-dependent current, while for HCN212 the increase at this time represents only 0.2% of the time-dependent current, reflecting the more rapid deactivation of HCN212. Thus, for a typical APD, significantly more HCN2 channels are likely to remain open at the start of diastole compared to HCN212 channels. While the former protocol explored Iins, the next protocol looked at the effect of voltage history on the time-dependent current (protocol 4, see Methods) by imposing varying prepulse durations. The +20 mV interpulse was fixed at 150 ms and the prepulse duration (to a voltage of −80 mV) varied between 150 ms and 2700 ms, in 850 ms increments (Fig. 5C and D). HCN2 channels at the shortest, 150 ms prepulse duration, corresponding to a short diastolic interval, exhibited significantly slower activation kinetics than for the other durations (P < 0.05). Similar to HCN2 channels, in HCN212 channels we also found a significant difference in the activation time constant at the 150 ms prepulse duration (P < 0.01). These results demonstrate that HCN2 and HCN212 channels expressed in myocytes display a prepulse-dependent activity as reported previously for other HCN channels (Wang et al. 2002; Proenza & Yellen, 2006).

Figure 5. Prepulse modulation of HCN channels.

A, representative HCN2 currents elicited by protocol 3. The inset shows the entire protocol, which includes an activating prepulse to −80 mV followed by a step to +20 mV with increasing interpulse interval and an additional activating step to −80 mV; the portion of the protocol not displayed in the current traces is represented by dashed lines. The double arrow labelled Iins represents the constant portion, or minimal, Iins. The double arrow labelled ΔIins indicates the enhancement of the instantaneous current observed at the shortest interpulse interval, reflecting the largest measured ΔIins. IHCN is the time-dependent steady-state current, and its magnitude is labelled for the same current trace. B, dependence of ΔIins,HCN2 (n = 3, squares) and ΔIins,HCN212 (n = 3, circles) on the interpulse interval. ΔIins was normalized to the amplitude of the time-dependent steady-state component of HCN current (ΔIins/IHCN). Data were fitted to a single exponential function; the 150 ms time point is highlighted by the vertical dashed line. C, representive HCN2 currents elicited by protocol 4. The inset shows the full protocol, with the portion omitted from the current traces represented by dashed lines. Prepulses (−80 mV) were evoked for different prepulse lengths (150 ms, 1000 ms, 1850 ms and 2700 ms) and the interpulse interval kept at 150 ms. D, activation time constant of HCN2 (n = 5, squares) and HCN212 (n = 4, circles) during the second −80 mV step. *Statistically significant (P < 0.05) difference from other prepulse durations in same HCN group by multiple comparison.

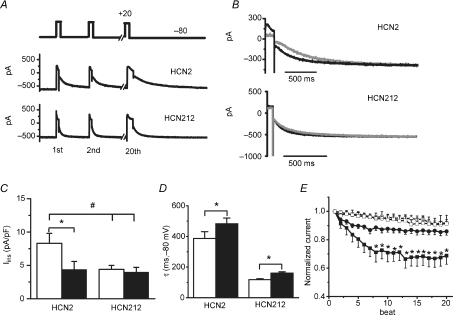

Taken together, Fig. 5D illustrates that for HCN channels both the magnitude of instantaneous and activation kinetics of the time-dependent current can vary for physiologically relevant APDs and diastolic intervals, and that HCN2 and HCN212 may quantitatively differ in this regard. We therefore addressed frequency-dependent modulation of HCN channel activity more directly, using two different protocols to approximate the time course of membrane potential changes in a beating myocyte at heart rates of 0.5 Hz (30 beats min−1) and 3.3 Hz (200 beats min−1), respectively. Figure 6A shows representative HCN currents elicited by a protocol with a depolarizing step to +20 mV lasting 150 ms from a holding potential of −80 mV followed by continuously repeating 20 square voltage pulses at 0.5 Hz. We compared these results to those obtained at 3.3 Hz. HCN currents vary at the two frequencies, particularly for HCN2, as seen when the final voltage steps are superimposed in Fig. 6B. Next, we examined the total instantaneous current (Iins). As shown in Fig. 6C, the magnitude of Iins of HCN2 channels following the 20th pulse at 0.5 Hz was greater than that at 3.3 Hz (8.3 ± 1.5 and 4.4 ± 1.2 pA pF−1, n = 8, P < 0.01). By contrast, the magnitude of Iins of HCN212 channels remained small and constant at 3.3 Hz and 0.5 Hz, 4.4 ± 0.6 pA pF−1 and 4.0 ± 0.7 pA pF−1 (n = 6, P > 0.05), respectively. Thus, compared with HCN212, HCN2 exhibits a large Iins at 0.5 Hz, presumably because a slower rate allows more current to activate during the period at −80 mV, and thus results in more current remaining as a consequence of incomplete deactivation during the pulse to +20 mV. Second, after 20 consecutive square voltage pulses followed by stepping back to −80 mV, the time constant of channel activation was measured by fitting to a single exponential function. As shown in Fig. 6D, both HCN2 and HCN212 channels at 0.5 Hz exhibit faster activation kinetics (smaller τ values) than at 3.3 Hz (for HCN2: 387 ± 44 ms to 483 ± 37 ms, P < 0.05; for HCN212: 118 ± 6 ms to 160 ± 9 ms, P < 0.05). In addition, as evident in Fig. 6B, the HCN2 delay prior to activation of the time-dependent component is decreased at 0.5 Hz (22.3 ± 1.6 ms versus 29.3 ± 2.6 ms at 3.3 Hz, P < 0.05). To assess the impact of the slower activation and longer delay at faster rates, we measured the magnitude of the time-dependent component of HCN currents at the 150 ms time point (IHCN,150 ms) following each of the 20 step pulses (Fig. 6E). The current contribution of both channels remained relatively stable throughout the stimulus train at 0.5 Hz, normalized to IHCN,150 ms of the first stimulus. By contrast, the currents of HCN2 and HCN212 significantly decreased at 3.3 Hz. However, the reduction in HCN2 was significantly greater than that in HCN212, beginning from the 8th stimulus (P < 0.05). These results indicate that the time-dependent component of HCN current present early in diastole decreases at faster pacing, and does so more markedly for HCN2 than for HCN212.

Figure 6. Frequency-dependent modulation of HCN currents in myocytes.

A, representative HCN currents elicited by repetitive steps from −80 mV to +20 mV for 150 ms at 0.5 Hz pacing rates. B, overlapping of the 20th HCN2 current (top) and HCN212 current (bottom) at 0.5 (black) and 3.3 Hz (grey) pacing rates. C, the changes of total Iins in HCN2 (n = 8) and HCN212 (n = 6) at 0.5 (white) and 3.3 Hz (black). *P < 0.05 versus 3.3 Hz by paired test; #P < 0.05 versus HCN212. D, activation time constant of HCN2 and HCN212 during the last −80 mV step at 0.5 (white) and 3.3 Hz (black) pacing rates. *P < 0.05 versus 3.3 Hz by paired test. E, the mean beat-to-beat changes of the time-dependent current of HCN2 (squares) and HCN212 (circles) at the 150 ms time point (IHCN,150 ms) during the 20-pulse train at 0.5 Hz (open symbols) and 3.3 Hz (filled symbols). *P < 0.05 versus HCN212 at 3.3 Hz by multiple comparison.

Discussion

We have over-expressed HCN channels in newborn rat ventricular myocytes with the aim of investigating which characteristics mainly account for the different biological pacemaker behaviour of HCN2 and HCN212 channels in vivo. The results show that: (1) both HCN2 and HCN212 channels expressed in myocytes have similar values of voltage dependence, current density and sensitivity to saturating cAMP, but HCN212 has faster activation and deactivation kinetics; (2) compared with HCN2, myocytes expressing HCN212 have a greater likelihood of exhibiting a faster but less regular rhythm, comparable to what is observed in vivo (Plotnikov et al. 2008); and (3) under non-equilibrium conditions, HCN2 and HCN212 exhibit different behaviour due to their different gating characteristics.

The pacemaker current is thought to play a role in generating and regulating pacemaker activity, but its relative importance is still controversial (DiFrancesco, 1993; Lakatta et al. 2003). However, when over-expressed such that a large current is generated in the diastolic potential range, there is now abundant evidence that the HCN gene family can create biological pacemaker activity (Plotnikov et al. 2004, 2008; Xue et al. 2005; Bucchi et al. 2006). The inward current contributed by If in the diastolic range of potentials is determined by the number of HCN channels opened during diastolic depolarization, which in turn depends on the steady-state open probability at a given potential and the rate at which the channel gating variable approaches the steady-state value (Bucchi et al. 2006). Under equilibrium conditions, HCN2 and HCN212 channels expressed in newborn rat ventricular myocytes have similar voltage dependence, current amplitude and responsiveness to saturating cAMP, but HCN212 exhibits the faster kinetics of HCN1, which have been ascribed, based on an allosteric model, to higher voltage sensor rates and to closed/open transitions having looser voltage-independent interactions (Altomare et al. 2001). HCN212 expression accelerated the spontaneous rate of newborn myocytes more than HCN2, which would be consistent with faster current kinetics as confirmed by the computer simulation. The slower deactivation kinetics of HCN2 contributes to the greater instantaneous current observed at slower rates immediately following a depolarizing/repolarizing step. That this did not result in a less negative MDP than in the case of HCN212 expression suggests that it is largely offset by the more rapid activation of HCN212. It should be noted that the computer simulation fits the macroscopic deactivation kinetics but does not account for the additional dynamic rate-dependent component, and so was not used to explore the basis of rate irregularity.

Interestingly, the irregular rhythm of rapid rates interspersed with pauses, observed with HCN212 in vivo, was also evident in the myocyte cultures. To gain insight into the mechanism underlying the different behaviour of HCN2 and HCN212 in myocytes, we activated the channels using voltage protocols designed to approximate the dynamic conditions that occur during spontaneous activity. As expected, we found that HCN channels were modulated by pacing frequency, but also that there were quantitative differences between HCN2 and HCN212.

If we first consider Iins, we notice that for depolarization periods comparable to typical APD, HCN2 will generate a greater instantaneous current than HCN212 at slow rates, but that the magnitude of Iins will decrease significantly as spontaneous rate increases (Figs 5B and 6C). In the case of HCN2, this would provide a form of negative feedback where the amount of Iins at the beginning of diastole will decrease as rate increases. Consistent with this interpretation, some studies have demonstrated that the current from incomplete deactivation of HCN channels might contribute to the stabilization of pacing rhythm. Analysis of slowly activating HCN4 channels suggested that enhancement of Iins could be facilitated by incomplete deactivation (Mistrik et al. 2006). The deletion of HCN4 in adult mice eliminates most of sinoatrial If and results in a cardiac arrhythmia characterized by recurrent sinus pauses similar to bursting behaviour in our study. Based on the results from a temporally controlled knockout of HCN4, If was proposed to function as a backup mechanism which guarantees stable pacemaking (Herrmann et al. 2007). However, since both activation and deactivation kinetics of HCN212 differ from those of HCN2, we cannot rule out a role of rapid activation in the observed rhythm irregularities.

In addition, the activation kinetics of the two HCN channels were dependent on the length of the hyperpolarizing prepulse (Figs 5C and D, and 6B and D). Compared to slow continuous pacing (long prepulse duration), a significant decrease in the activation kinetics of HCN channels at fast pacing (short prepulse duration) was observed. Further, as previously reported for native pacemaker current (DiFrancesco, 1984), the delay shortens at slower rates (i.e. for a longer negative prepulse), which can both add to the instantaneous component and result in a greater time-dependent component at a fixed but short time point during diastole. As a result of the slower activation and increased delay with faster rates, during a series of 20 simulated action potentials at 3.3 Hz, the time-dependent component of IHCN2 (measured at 150 ms) decreased significantly more than that of IHCN212. This would again be consistent with a more robust negative feedback mechanism for HCN2 than HCN212. Thus, under consecutive pacing at a rapid rate, the negative feedback characteristics of both the instantaneous and time-dependent components of HCN2 channels may favour the maintenance of a stable rhythm. For HCN212, where the kinetics make it less likely for incomplete deactivation to occur, and where activation kinetics are less affected by frequency over the range studied, the negative feedback is less robust. As a result, if spontaneous rate increases for any reason, the exogenous pacemaker current is less able to compensate and restore a slower rate. If the rate becomes fast enough, other mechanisms such as overdrive suppression may come into play, leading to the observed pauses and rhythm irregularities.

Our results provided new insight for designing future HCN constructs for the purpose of creating a biological pacemaker. Myocytes expressing HCN212 with fast activation kinetics have a faster spontaneous rate, which may be a desirable feature. However, the slower kinetics of HCN2 channels means that both the instantaneous and time-dependent components of the current exhibit greater frequency dependence (within the 0.5–3.3 Hz range studied), which serves to stabilize rhythmicity. By this reasoning, an HCN construct with intermediate kinetics between HCN2 and HCN212 might strike a more favourable balance. Alternatively, it might prove fruitful to uncouple activation and deactivation kinetics, such that a construct exhibits the rapid activation kinetics of HCN212 but the slower deactivation kinetics of HCN2. While the separation of activation and deactivation kinetics is not clear-cut, allosteric models suggest they are separable parameters (DiFrancesco, 1999), and detailed insight into the structure and function of HCN channels may provide the required information in the future. For example, using chimeras between HCN2 and HCN4, it was recently reported that the S1–S2 region plays a crucial role in deactivation kinetics (Proenza & Yellen, 2006).

In summary, we propose that frequency-dependent modulation of HCN channels with distinct activation/ deactivation kinetics contributes, at least in part, to the different behaviour of HCN2 and HCN212 observed during in vivo expression. The dynamic, or non-equilibrium, characteristics of HCN constructs should be considered in developing a future HCN-based biological pacemaker. Spontaneously beating cultures of newborn myocytes represent a useful model system for both characterizing the biophysical properties of new constructs and for assessing the effect of these constructs on both rate and rhythm.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs Dario DiFrancesco, Ira Cohen and Michael Rosen for helpful comments on the manuscript. We thank Ms Haejung Chung and Ms Ming Chen for technical support. This study was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute program project grant HL-28958, and the Boston Scientific Corp. X. Zhao was partially supported by the Specialized Research Fund for the “135” Project (RC2003019) from Jiangsu Province of China.

Author's present address

X. Zhao: Division of Cardiology, The first affiliated hospital of Soochow University, Su Zhou, China.

Supplemental material

Online supplemental material for this paper can be accessed at:

http://jp.physoc.org/cgi/content/full/jphysiol.2008.163444v1/DC1

References

- Accili EA, Proenza C, Baruscotti M, DiFrancesco D. From funny current to HCN channels: 20 years of excitation. News Physiol Sci. 2002;17:32–37. doi: 10.1152/physiologyonline.2002.17.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altomare C, Bucchi A, Camatini E, Baruscotti M, Viscomi C, Moroni A, DiFrancesco D. Integrated allosteric model of voltage gating of HCN channels. J Gen Physiol. 2001;117:519–532. doi: 10.1085/jgp.117.6.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azene EM, Xue T, Marban E, Tomaselli GF, Li RA. Non-equilibrium behavior of HCN channels: insights into the role of HCN channels in native and engineered pacemakers. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;67:263–273. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biel M, Ludwig A, Zong X, Hofmann F. Hyperpolarization-activated cation channels: a multi-gene family. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;136:165–181. doi: 10.1007/BFb0032324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucchi A, Baruscotti M, Robinson RB, DiFrancesco D. Modulation of rate by autonomic agonists in SAN cells involves changes in diastolic depolarization and the pacemaker current. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;43:39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucchi A, Plotnikov AN, Shlapakova I, Danilo PJ, Kryukova Y, Qu J, Lu Z, Liu H, Pan Z, Potapova I, KenKnight B, Girouard S, Cohen IS, Brink PR, Robinson RB, Rosen MR. Wild-type and mutant HCN channels in a tandem biological-electronic cardiac pacemaker. Circulation. 2006;114:992–999. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.617613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFrancesco D. Characterization of the pace-maker current kinetics in calf Purkinje fibres. J Physiol. 1984;348:341–367. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFrancesco D. Pacemaker mechanisms in cardiac tissue. Ann Rev Physiol. 1993;55:455–472. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.55.030193.002323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFrancesco D. Dual allosteric modulation of pacemaker (f) channels by cAMP and voltage in rabbit SA node. J Physiol. 1999;515:367–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.367ac.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann S, Stieber J, Stockl G, Hofmann F, Ludwig A. HCN4 provides a ‘depolarization reserve’ and is not required for heart rate acceleration in mice. EMBO J. 2007;26:4423–4432. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurata Y, Hisatome I, Imanishi S, Shibamoto T. Dynamical description of sinoatrial node pacemaking: improved mathematical model for primary pacemaker cell. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H2074–H2101. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00900.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakatta EG, Maltsev VA, Bogdanov KY, Stern MD, Vinogradova TM. Cyclic variation of intracellular calcium: a critical factor for cardiac pacemaker cell dominance. Circ Res. 2003;92:45e–50. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000055920.64384.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieu DK, Chan YC, Lau CP, Tse HF, Siu CW, Li RA. Overexpression of HCN-encoded pacemaker current silences bioartificial pacemakers. Heart Rhythm. 2008. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mistrik P, Pfeifer A, Biel M. The enhancement of HCN channel instantaneous current facilitated by slow deactivation is regulated by intracellular chloride concentration. Pflugers Arch. 2006;452:718–727. doi: 10.1007/s00424-006-0095-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plotnikov AN, Bucchi A, Shlapakova I, Danilo P, Jr, Brink PR, Robinson RB, Cohen IS, Rosen MR. HCN212-channel biological pacemakers manifesting ventricular tachyarrhythmias are responsive to treatment with If blockade. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5:282–288. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2007.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plotnikov AN, Sosunov EA, Qu J, Shlapakova IN, Anyukhovsky EP, Liu L, Janse MJ, Brink PR, Cohen IS, Robinson RB, Danilo PJ, Rosen MR. Biological pacemaker implanted in canine left bundle branch provides ventricular escape rhythms that have physiologically acceptable rates. Circulation. 2004;109:506–512. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000114527.10764.CC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proenza C, Angoli D, Agranovich E, Macri V, Accili EA. Pacemaker channels produce an instantaneous current. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:5101–5109. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106974200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proenza C, Yellen G. Distinct populations of HCN pacemaker channels produce voltage-dependent and voltage-independent currents. J Gen Physiol. 2006;127:183–190. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Protas L, Robinson RB. Neuropeptide Y contributes to innervation-dependent increase in ICa,L via ventricular Y2 receptors. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1999;277:H940–H946. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.3.H940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu J, Altomare C, Bucchi A, DiFrancesco D, Robinson RB. Functional comparison of HCN isoforms expressed in ventricular and HEK 293 cells. Pflugers Arch. 2002;444:597–601. doi: 10.1007/s00424-002-0860-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu J, Barbuti A, Protas L, Santoro B, Cohen IS, Robinson RB. HCN2 over-expression in newborn and adult ventricular myocytes: distinct effects on gating and excitability. Circ Res. 2001;89:e8–e14. doi: 10.1161/hh1301.094395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu J, Plotnikov AN, Danilo PJ, Shlapakova I, Cohen IS, Robinson RB, Rosen MR. Expression and function of a biological pacemaker in canine heart. Circulation. 2003;107:1106–1109. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000059939.97249.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson RB, Brink PR, Cohen IS, Rosen MR. If and the biological pacemaker. Pharmacol Res. 2006;53:407–415. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoro B, Tibbs GR. The HCN gene family: molecular basis of the hyperpolarization-activated pacemaker channels. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;868:741–764. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb11353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Chen S, Nolan MF, Siegelbaum SA. Activity-dependent regulation of HCN pacemaker channels by cyclic AMP: signaling through dynamic allosteric coupling. Neuron. 2002;36:451–461. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00968-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Chen S, Siegelbaum SA. Regulation of hyperpolarization-activated HCN channel gating and cAMP modulation due to interactions of COOH terminus and core transmembrane regions. J Gen Physiol. 2001;118:237–250. doi: 10.1085/jgp.118.3.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue T, Cho HC, Akar FG, Tsang SY, Jones SP, Marban E, Tomaselli GF, Li RA. Functional integration of electrically active cardiac derivatives from genetically engineered human embryonic stem cells with quiescent recipient ventricular cardiomyocytes: insights into the development of cell-based pacemakers. Circulation. 2005;111:11–20. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000151313.18547.A2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.