Summary

Background

The most serious complication of subcutaneous fat necrosis (SCFN), a rare condition of the newborn characterized by indurated purple nodules, is hypercalcaemia. However, the mechanism for this hypercalcaemia remains unclear.

Objectives

To determine whether the hypercalcaemia associated with SCFN involves expression of the vitamin D-activating enzyme 25-hydroxyvitamin D3-1α-hydroxylase (1α-hydroxylase) in affected tissue.

Methods

Skin biopsies from two male patients with SCFN and hypercalcaemia were taken. The histological specimens were assessed using a polyclonal antibody against 1α-hydroxylase.

Results

Histology in both cases showed strong expression of 1α-hydroxylase protein (brown staining) within the inflammatory infiltrate associated with SCFN. This was consistent with similar experiments in other granulomatous conditions.

Conclusions

Hypercalcaemia in SCFN appears to be due to abundant levels of 1α-hydroxylase in immune infiltrates associated with tissue lesions. This is consistent with previous observations of extrarenal 1α-hydroxylase in skin from other granulomatous conditions such as sarcoidosis and slack skin disease.

Keywords: hypercalcaemia, subcutaneous fat necrosis, vitamin D

Neonatal subcutaneous fat necrosis (SCFN) is a rare granulomatous condition that occurs after trauma or asphyxia at birth. It is characterized by indurated purple nodules on the face, trunk and proximal extremities. This may be followed by hypercalcaemia, proposed causes of which include increased prostaglandin activity, calcium release from necrotic fat cells and increased production of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 [1,25(OH)2D3]. Although elevated serum levels of 1,25(OH)2D3 have been documented in at least three published reports,1-3 its source has not previously been identified.

In view of the similarities to sarcoidosis, another granulomatous disorder where hypercalcaemia results from extrarenal synthesis of 1,25(OH)2D3 catalysed by the enzyme 25-hydroxyvitamin D3-1α-hydroxylase (1α-hydroxylase), we investigated whether localized expression of 1α-hydroxylase is also a feature of SCFN.

Subjects and methods

The two male infants were born at term by emergency caesarean section for fetal distress. Each had developed an abnormal appearance of the skin of the back within 4 days consisting of extensive deep indurated subcutaneous plaques of a reddish purple colour (Fig. 1). The clinical features of one infant have been described previously.4

Fig 1.

An infant with an area of subcutaneous fat necrosis on the back.

Hypercalcaemia became apparent in each infant 4−8 weeks after birth with evidence of nephrocalcinosis on renal ultrasound. The calcium levels of our subjects reached 4·07 mmol L−1 and 3·41 mmol L−1, well above the normal range (2·15−2·70 mmol L−1). There was no evidence of increased bone turnover as serum levels of phosphate and alkaline phosphatase were within normal limits and that of parathyroid hormone appropriately suppressed. Circulating levels of the substrate for 1α-hydroxylase, 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 (25OHD3) were within the normal range [≤ 25 ng mL−1 (62·5 nmol L−1)], but 1,25(OH)2D3 was not measured at the time of presentation in either infant. They were treated with intravenous fluid rehydration, furosemide and oral corticosteroids with resolution of the hypercalcaemia and skin changes within 4 weeks.

Skin biopsies (5 μm thick) embedded in paraffin for routine histology were later assessed for expression of 1α-hydroxylase. Ethical permission was obtained from the Local Research Ethics Committee (LREC No. RRK2608). Sections were de-waxed, immersed in 0·01 mol L−1 citrate buffer (pH 6·0) and heated in a pressure cooker at 103 kPa for 2 min. Slides were incubated with an in-house polyclonal antibody (1 : 150) against a mouse 1α-hydroxylase amino acid sequence (peptide 266−289) (The Binding Site, Birmingham, U.K.)5,6 in 10% normal swine serum for 45 min at 25 °C. After rinsing with Tris-buffered saline for 15 min, donkey-antisheep-immunoperoxidase (1 : 100) was added to the sections for 45 min. Slides were developed using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (2·5 mg mL−1) (positive staining brown) and were counterstained with Mayer's haematoxylin (blue). Control experiments included omission of primary antibody and use of primary antibody preabsorbed with 100-fold excess of immunizing peptide.

Results

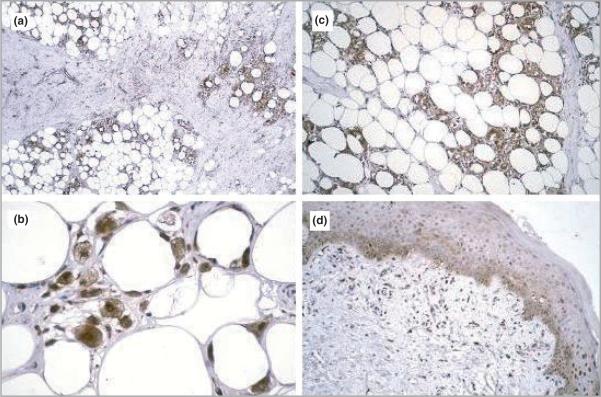

In both cases routine skin histology showed a dense mononuclear cell infiltrate within the subcutaneous fat with needle-shaped clefts typical of SCFN. Both SCFN cases showed strong expression of 1α-hydroxylase protein (brown staining) within the inflammatory infiltrate (Fig. 2a–c) in contrast to normal skin where staining to 1α-hydroxylase is restricted to keratinocytes in the basal layer of the epidermis (Fig. 2d). The staining observed in SCFN skin was similar to that observed in patients with sarcoidosis6 and slack skin disease,7 where expression of 1α-hydroxylase is also characteristic of inflammatory cells.

Fig 2.

Expression of 25-hydoxyvitamin D3-1α-hydroxylase (1α-hydroxylase) protein in skin from two male infants with subcutaneous fat necrosis. Subcutaneous fat with partial fibrosis and dense infiltrate. This dense filtrate of mononuclear cells is stained strongly for 1α-hydroxylase protein (a–c). Original magnification: (a) × 100, (b) × 150, (c) × 300. (d) Normal epidermis with expression of 1α-hydroxylase protein within the stratum basalis.

Discussion

SCFN occurs in the newborn usually following perinatal stress such as trauma, hypothermia or fetal distress, as in the case of our subjects. Both had typical skin lesions and needed treatment with a low-calcium milk diet, intravenous fluid rehydration, furosemide and oral corticosteroids for correction of hypercalcaemia, a complication with significant morbidity. There have been recent reports of treatment of the hypercalcaemia associated with this condition with bisphosphonates such as pamidronate3 and etidronate8 but our observations do not support the hypothesis of increased bone turnover to explain hypercalcaemia. Instead they demonstrate that the hypercalcaemia seen in SCFN is related to aberrant extrarenal production of 1,25(OH)2D3.

This is consistent with observations seen in sarcoidosis6 and slack skin disease7 where hypercalcaemia has been linked to extrarenal expression of 1α-hydroxylase and associated dysregulated synthesis of 1,25(OH)2D3. Ideally we would have liked to have shown elevated levels of 1,25(OH)2D3 in our subjects. However, there was a time lapse of several years between the presentation of the infants and the revaluation of the skin biopsies for the purpose of this study. Elevated levels of this active form of vitamin D have been documented in at least three published reports of this condition as the cause of associated hypercalcaemia.1-3

Precursor 25OHD3 is metabolized to 1,25(OH)2D3 by the enzyme 1α-hydroxylase, which is expressed predominantly by the kidney but is also detectable in cells from extrarenal tissues, notably macrophages, dendritic cells, keratinocytes and placental cells.9 Within the kidney, expression of 1α-hydroxylase is stimulated by parathyroid hormone and hypocalcaemia with inhibition of the enzyme being facilitated through a negative feedback mechanism involving 1,25(OH)2D3 itself. Although extrarenal synthesis of 1,25(OH)2D3 is catalysed by the same 1α-hydroxylase as found in the kidney, the regulation of this enzyme in peripheral tissues has been shown to be distinct from that seen in kidney cells. In particular, the increased expression of 1α-hydroxylase that is observed in cells such as macrophages following immunological challenge10 does not appear to be readily attenuated via classical 1,25(OH)2D3 feedback control. This may explain why localized synthesis of 1,25(OH)2D3 within tissues such as the skin has the potential to accumulate and then spill over into the general circulation. Extrarenal 1α-hydroxylase, unlike the renal version of this enzyme, is also sensitive to steroids. This is consistent with our observations, and those of others, concerning the effects of steroid in babies with SCFN.

Within the skin, expression of 1α-hydroxylase is normally restricted to the basal layer of the epidermis as shown in Figure 2d. In diseases such as psoriasis,6 sarcoidosis6 and slack skin disease,7 this distribution is dysregulated. This is the first time that extrarenal expression of 1α-hydroxylase has been demonstrated in SCFN lesions. In contrast to patients with psoriasis, where aberrant 1α-hydroxylase expression is restricted to the dysregulated epidermal cells,6 the dysregulated enzyme in SCFN appears to be associated with disease-associated immune cells. This may explain the lack of hypercalcaemic complications in psoriasis in contrast to SCFN and other granulomatous diseases.

In summary, we have demonstrated the presence of extrarenal 1α-hydroxylase in immune cells associated with SCFN. We hope that future therapeutic advances in the hypercalcaemia of other granulomatous skin diseases may be extrapolated to SCFN.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Kruse K, Irle U, Uhlig R. Elevated 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D serum concentrations in infants with subcutaneous fat necrosis. J Pediatr. 1993;122:460–3. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)83441-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finne PH, Sanderud J, Aksnes L, et al. Hypercalcaemia with increased and unregulated 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D production in a neonate with subcutaneous fat necrosis. J Pediatr. 1988;112:792–4. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(88)80706-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alos N, Eugene D, Fillion M, et al. Pamidronate: treatment for severe hypercalcemia in neonatal subcutaneous fat necrosis. Horm Res. 2006;65:289–94. doi: 10.1159/000092602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewis HM, Ferryman S, Gatrad AR, Moss C. Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn associated with hypercalcaemia. J Roy Soc Med. 1994;87:482–3. doi: 10.1177/014107689408700819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zehnder D, Bland R, Walker EA, et al. Expression of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3–1α-hydroxylase in the human kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:2465–73. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V10122465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zehnder D, Bland R, Williams MC, et al. Extrarenal expression of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 1α-hydroxylase. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:888–94. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.2.7220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karakelides H, Geller J, Schroeter A, et al. Vitamin D mediated hypercalcemia in slack skin disease: evidence for involvement of extrarenal 25-hydroxyvitamin D 1α-hydroxylase. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:1496–9. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rice AM, Rivkees SA. Etidronate therapy for hypercalcemia in subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn. J Pediatr. 1999;134:349–51. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(99)70462-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hewison M, Zehnder D, Chakraverty R, Adams JS. Vitamin D and barrier function: a novel role for extra-renal 1α-hydroxylase. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2004;215:31–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu PT, Stenger S, Li H, et al. Toll-like receptor triggering of a vitamin D-mediated human antimicrobial response. Science. 2006;311:1770–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1123933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]