Abstract

IL-1 causes a marked increase in the degree of expansion of naïve and memory CD4 T cells in response to challenge with their cognate antigen. The response occurs when only specific CD4 T cells can respond to IL-1β, is not induced by a series of other cytokines and does not depend on IL-6 or CD-28. When WT cells are primed in IL-1R1−/− recipients, IL-1 increases the proportion of cytokine-producing transgenic CD4 T cells, especially IL-17- and IL-4-producing cells, strikingly increases serum IgE levels and serum IgG1 levels. IL-1β enhances antigen-mediated expansion of in vitro primed Th1, Th2, and Th17 cells transferred to IL-1R1−/− recipients. The IL-1 receptor antagonist diminished responses to antigen plus lipopolysaccharide (LPS) by ≈55%. These results indicate that IL-1β signaling in T cells markedly induces robust and durable primary and secondary CD4 responses.

Keywords: cytokines, inflammasome, Th1, Th17, Th2

T cell responses to cognate antigens are minimal in the absence of adjuvants. Adjuvant effects often depend on engagement of Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and/or other microbial sensors in dendritic cells (DCs) and other innate immune cells, leading to the activation of DC (1). In turn, activated DCs provide enhanced stimulation for CD4 T cell responses (1).

Proinflammatory cytokines are often present at elevated levels in the course of inflammatory responses and infections. We queried whether these cytokines, particularly the prototypic proinflammatory cytokine IL-1β (2), might have a direct impact on CD4 T cell expansion.

IL-1 plays a significant role in immune responses to microorganisms as shown by greater and earlier morbidity and mortality to infections by various bacteria and viruses in the absence of IL-1R1 or MyD88 (3–5). In humans, deficiency in IRAK-4, which is involved in IL-1 signal transduction (6), leads to recurrent invasive bacterial infections (7); neutralization of IL-1 signaling by an IL-1 antagonist has caused septicemia in treated individuals (8). IL-1 plays a major role in the induction of Th17 cells in humans (9). Th17 cells have been implicated in protective responses to extracellular bacteria (10, 11), to Toxoplasma gondii (12) and to fungi (13); protective immunity in mice vaccinated with antigens from M. tuberculosis is mediated by IL-17 (14). Humans with hyper IgE syndrome, who have defects in development of IL-17 producing cells, have recurrent infection with extracellular bacteria and fungi (15).

Injection of IL-1α at the time of immunization has been reported to enhance primary responses, although to a relatively modest degree (16, 17). In the latter study, the IL-1 effect was reported to be mediated through the action on antigen presenting cells (APCs) and its effect depended on the expression of CD28 on the part of the responding T cells, implying that it may have mimicked the action of TLR-engaging or inflammasome-activating adjuvants on the ability of APC to mature. Indeed it had been shown that IL-1 plays a role in the regulation of DC activation (18, 19), enabling the production of cytokines and enhancing the differentiation of naïve T cells (19, 20).

We wished to determine whether continuous exposure to IL-1 and other proinflammatory cytokines might have a more robust effect than observed with single injections and might target the responding T cells as well as, or in preference to, DCs and/or other APCs, as might be anticipated from the role of IL-1 in promoting Th17 differentiation (9).

Results

IL-1 Enhances Primary and Secondary CD4 T Cell Responses.

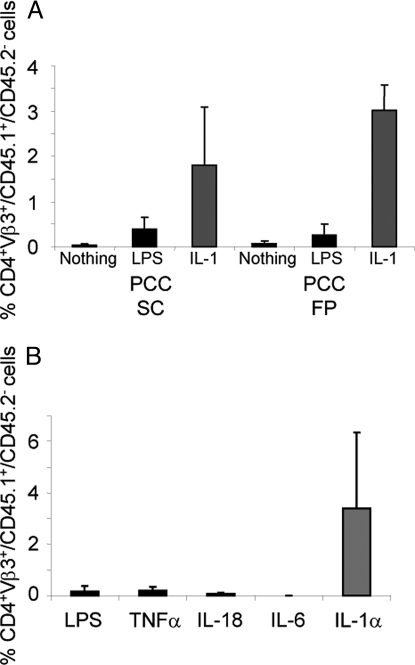

Lymph node cells specific for a cytochrome C peptide/I-Ek complex, from 5C.C7 Rag2−/− CD45.1 donors, were injected into normal CD45.2 B10.A recipients. Recipients were immunized with pigeon cytochrome C (PCC) together with nothing, LPS or IL-1β (administered through a miniosmotic pump). On day 7, mice that received IL-1 had a >4-fold greater increase in the number of 5C.C7 cells among their peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) than mice that received LPS (Fig. 1A). When footpad immunization was used, the IL-1 group had a 12-fold greater response than the LPS group. Comparable results were obtained by analysis of lymph nodes and spleens from immunized mice (Fig. S1A).

Fig. 1.

IL-1 augments primary responses. (A) IL-1 is superior to LPS in augmenting primary immune responses in vivo. The 5C.C7/RAG-2−/−/CD45.1 B10.A lymph node cells (1.5 × 106) were transferred IP into CD45.2 B10.A mice. Ten days later, mice were immunized by s.c. or footpad (FP) injection of 500 μg of PCC only, with 25 μg of LPS or with rIL-1β (10 μg) in a miniosmotic pump. One week after priming, the percentage of CD4+/Vβ3+/CD45.1+/CD45.2− (i.e., 5C.C7) cells (Mean + SEM) among the PBMCs was determined as described in Materials and Methods. (B) IL-1 is superior to LPS and to other proinflammatory cytokines in augmenting primary immune responses in vivo. The 5C.C7/RAG-2−/−/CD45.1 B10.A lymph node (1 × 106) and spleen (2.5 × 106) cells were transferred IP into CD45.2 B10.A mice. Seven days later, mice were immunized by implantation of miniosmotic pumps containing 1 mg of PCC with either rIL-1α (10 μg), rIL-6 (10 μg), rIL-18 (10 μg), rTNFα (10 μg) or LPS (25 μg). One week after priming, the percentage of CD4+/Vβ3+/CD45.1+/CD45.2− cells among the PBMCs was determined as described in Materials and Methods.

Among a series of proinflammatory cytokines tested, including TNFα, IL-6, IL-18 and IL-33, only IL-1 increased the degree of expansion of 5C.C7 cells in response to PCC immunization (Fig. 1B and data not shown). IL-1α and IL-1β displayed similar potency (Fig. S1B).

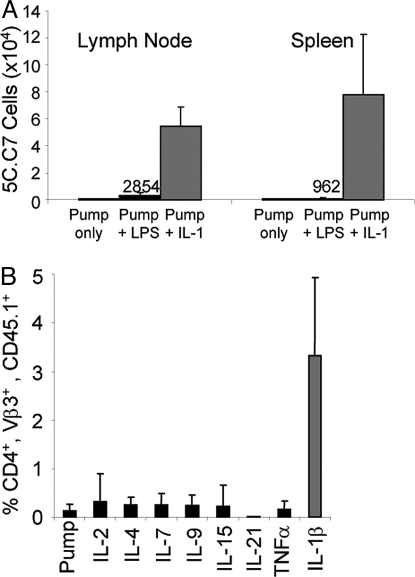

Priming in the presence of IL-1β gave rise to greater persistence of memory cells than did priming in the presence of LPS. Mice that had received 5C.C7 cells were primed with PCC in a miniosmotic pump. Some animals additionally received LPS or IL-1. Sixteen months later, the mice that had received IL-1 had 54,000 5C.C7 in their lymph nodes and 77,000 in their spleens whereas those that had received LPS had barely detectable numbers of 5C.C7 cells and those that had not, undetectable numbers (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

The IL-1 effect persists and IL-1 acts on memory cells. (A) 5C.C7 cells primed in the presence of IL-1 persist. The 5C.C7/RAG-2−/−/CD45.2 B10.A lymph node (1 × 106) and spleen (2 × 106) cells were transferred IP into CD45.1 B10.A mice. Seven days later, mice were immunized by implantation of miniosmotic pumps containing PCC (1 mg) alone or with LPS (25 μg) or IL-1 (10 μg). Sixteen months later, the number of CD4+/Vβ3+/CD45.2+ cells in lymph nodes and spleens was determined. (B) IL-1, but not other cytokines, induces robust secondary responses in vivo. The 5C.C7/RAG-2−/−/CD45.1 B10.A lymph node (1 × 106) and spleen (2 × 106) cells were transferred IP into CD45.2 B10.A mice. Seven days later, mice were immunized by s.c. injection of 1 mg of PCC with 25 μg of LPS. Seven months after priming, the mice were boosted by implantation of miniosmotic pumps containing 1 mg of PCC with either rIL-1β (10 μg), rIL-2 (10 μg), rIL-4 (10 μg), rIL-7 (10 μg), rIL-9 (10 μg), rIL-15 (10 μg), rIL-21 (10 μg), rTNFα (10 μg), or no additional cytokine. One week after the boost, the percentage of CD4+/Vβ3+/CD45.1+ cells among PBMCs was determined.

The response of memory cells was also enhanced by IL-1. Mice received 5C.C7 cells and were primed with PCC administered s.c. with LPS. Seven months later they were challenged with PCC with or without the addition of exogenous cytokines.

IL-1β caused a 26-fold greater expansion of memory cells compared with the expansion caused by antigen alone. No significant increase in antigen-mediated expansion of primed cells was caused by IL-2, IL-4, IL-7, IL-9, IL-15, IL-21 or TNFα (Fig. 2B).

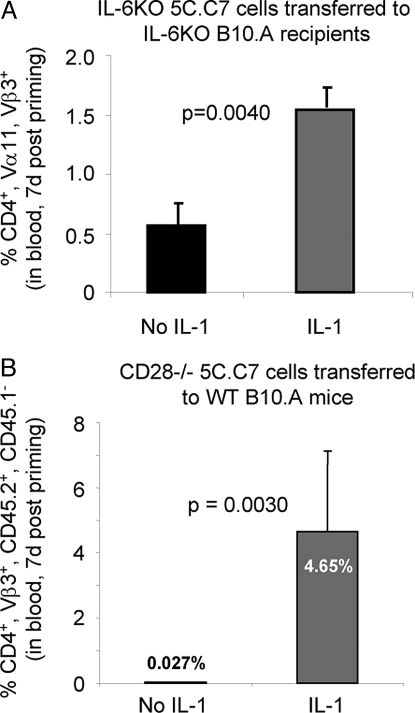

IL-6 or CD28 Are Not Required for the IL-1 Enhanced Response.

CD4 T cells from 5C.C7 donors deficient in IL-6 were transferred into IL-6-deficient B10.A recipients. Administration of IL-1β with antigen caused a 3-fold greater increase in the frequency of 5C.C7 cells than occurred in comparable mice that had not received IL-1 (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Neither IL-6 or CD28 are needed. (A) IL-6 is not essential for the IL-1-mediated enhancement of primary immune responses. The 5C.C7/RAG-2−/−/IL-6−/− B10.A lymph node cells (1.5 × 105) were transferred IP into CD3ε−/−, IL-6−/− B10.A mice. Eight days later, mice were immunized by implantation of miniosmotic pumps containing 1 mg of PCC with or without rIL-1β (10 μg). One week after priming, the percentage of CD4+/Vα11+/Vβ3+ cells among PBMCs was determined as described in Materials and Methods. (B) IL-1 enhances the response of antigen-stimulated CD28−/− 5C.C7 cells. The 5C.C7/RAG-2−/−/CD28−/− CD45.2 B10.A lymph node cells (1 × 106) were transferred IP into normal CD45.1 B10.A mice. Eight days later, mice were immunized by implantation of miniosmotic pumps containing 500 μg of PCC with or without rIL-1β (10 μg). After 7 days, the percentage of CD4+/Vβ3+/CD45.2+/CD45.1− cells among PBMCs was determined as described in Materials and Methods.

When CD28−/− 5C.C7 cells were stimulated in intact B10.A recipients, IL-1 markedly enhanced their response to PCC, indicating that CD28 expression on responding T cells is not essential for the IL-1 effect (Fig. 3B).

IL-1 Enhancement Is Seen in Responses by Polyclonal Cells.

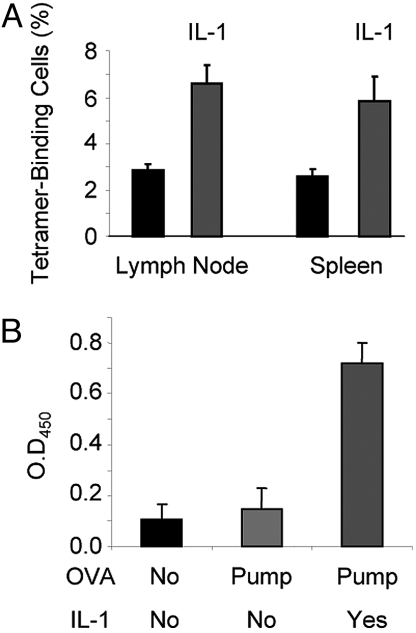

C57BL/6 mice were immunized using a miniosmotic pump with or without IL-1 with a peptide representing positions 61 to 80 of the lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) glycoprotein, the dominant CD4 epitope (21). Seven days later, among CD44bright, Vα2+ CD4 lymph node T cells from mice immunized with peptide and IL-1, 6.6% of the cells bound a tetramer composed of the gp 66–77 peptide bound to the I-Ab class II MHC molecule, compared with 2.9% of comparable cells from mice immunized with peptide without IL-1 (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

IL-1 enhances polyclonal responses. (A) IL-1 increases the frequency of tetramer-binding CD4 cells in mice immunized with an LCMV peptide. C57BL/6 mice were immunized by implantation of miniosmotic pumps containing 100 μg of the gp61–80 LCMV peptide with or without rIL-1β(10 μg). After 7 days, the percentage of cells stained with the gp66–77 tetramer among the CD4+/Vα2+/CD44high population in the lymph nodes and spleens was determined. (B) IL-1 enhances the IgG1 anti-ovalbumin antibody response. C57BL/6 mice were immunized by implantation of miniosmotic pumps containing 1 mg ovalbumin with or without rIL-1β(10 μg). Sera were obtained 14 days after immunization and IgG1 anti-ovalbumin antibodies were determined at a 1:100 dilution by sandwich ELISA.

We also tested the effect of IL-1 on production of anti-ovalbumin (OVA) antibody 14 days after immunization of B6 mice with OVA with or without IL-1. Immunization with OVA in a miniosmotic pump caused only a modest increase in serum antibody titer over that seen in unimmunized mice. By contrast, mice that also received IL-1 showed a striking increase in their ELISA titer of the T cell-dependent IgG1 anti-OVA antibody (Fig. 4B) further indicating that IL-1 enhanced normal CD4 T cell mediated immune responses.

Increased Cell Proliferation Cannot Completely Account for the IL-1 Effect.

The 5C.C7 cells were labeled with 5,6-carboxy-succinimidyl-fluoresceine-ester (CFSE) and transferred to B10.A recipients that were immunized with PCC in a miniosmotic pump with or without IL-1. On days 2, 3 and 4, cells from mice that had received IL-1 showed an increased number of cell divisions ranging from 0.6 to 1.1 (Table S1). Although the increased cell division on day 2 could account for most of the increase in cell number mediated by IL-1 at that time, it could only account for a small portion of the increased expansion in cell number seen on days 3 and 4. On those days, IL-1 caused an ≈9-fold (day 3) or 7- to 8-fold (day 4) greater expansion. Thus, increased survival is the dominant factor in the IL-1-mediated enhancement of expansion at later times.

T Cells Are a Major Target of IL-1.

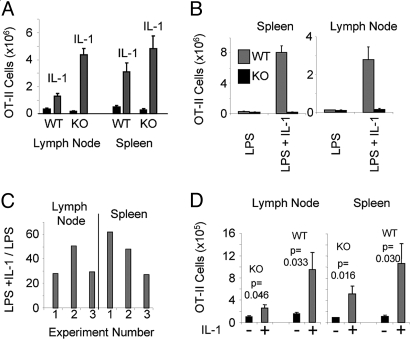

Lymph node CD4 T cells of OT-II mice were transferred into IL-1R1−/− C57BL/6 mice. Upon immunization with OVA plus LPS, the expansion of the OT-II cells was 26.2-fold greater in the lymph node in the presence of IL-1 than in its absence and 17.4-fold greater in the spleen (Fig. 5A). Comparable results was obtained in a second experiment and even more striking IL-1-mediated enhancement in a related set of 3 experiments in which the recipient IL-1R1−/−C57BL/6 mice were on a Rag1−/− background possessed the 5C.C7 TCR transgene (B6 1L-1R1−/− Rag1−/−) (Fig. 5C). The greater expansion observed when WT T cells were transferred to IL-1R1−/− recipients compared with WT T cells transferred to WT recipients may be explained by the higher concentration of serum IL-1 in the IL-1R1−/− recipients (Fig. S2) presumably because of the absence of cells other than responding T cells that can use IL-1.

Fig. 5.

IL-1 acts on T cells. (A) IL-1 enhances responses of WT T cells in IL-1R1−/− recipients. OT-II/RAG1−/− C57BL/6 lymph node cells (5 × 105) enriched for CD4 T cells, were transferred IP into WT or IL-1R1−/− (KO) C57BL/6 mice. Seven days later, mice were immunized by injection of 1 mg of OVA s.c. with LPS (25 μg) with or without rIL-1β (10 μg) in a miniosmotic pump. Seven days after immunization, the number and percentage of CD4+/Vα2+/Vβ5+ cells in the lymph nodes and spleens were determined as described in Materials and Methods. (B) IL-1-induced expansion of antigen-stimulated CD4 cells is cell autonomous. OT-II/RAG1−/− CD45.1 C57BL/6 and IL-1R1−/− OT-II/RAG1−/− C57BL/6 lymph node cells were transferred IP into B6 1L-1R1−/− Rag2−/− mice. Nine days later, mice were immunized by injection of 500 μg of OVA and 25 μg of LPS s.c. with or without rIL-1β (5 μg) administered through a miniosmotic pump. Seven days after immunization, the percentage of CD45.1 and CD45.2 CD4+/Vα2+/Vβ5+ cells in the lymph nodes and spleens was determined as described in Materials and Methods and the number of WT and IL-1R1−/− (KO) OT-II cells in these organs calculated. (C) IL-1 enhances responses of WT T cells in 1L-1R1−/− Rag1−/− recipients. OT-II/RAG1−/− C57BL/6 lymph node cells (5 × 105) that had been enriched for CD4 T cells were transferred IP into B6 1L-1R1−/− Rag1−/− mice. Seven to 9 days later, mice were immunized by injection of 500 μg of OVA s.c. with LPS (25 μg) with or without rIL-1β (5 μg) that was administered in a miniosmotic pump. Seven days after immunization, the number and percentage of CD4+/Vα2+/Vβ5+ cells in the lymph nodes and spleens were determined as described in Materials and Methods. The ratios of OT-II cells in mice immunized with and without IL-1 from 3 independent experiments are presented. (D) IL-1 induces less expansion of antigen-stimulated IL-1R1−/− OT-II cells than of WT OT-II cells in WT recipients. OT-II/RAG1−/− C57BL/6 (WT) or IL-1R1−/− OT-II/RAG1−/− C57BL/6 (KO) lymph node cells were transferred IP into WT C57BL/6 mice. Nine days later, mice were immunized by injection of 500 μg of OVA and 25 μg of LPS s.c. with or without rIL-1β (5 μg) in a miniosmotic pump. Seven days after immunization, the percentage of CD4+/Vα2+/Vβ5+ cells in the lymph nodes and spleens was determined as described in Materials and Methods, and the number of OT-II cells the organs was calculated.

When WT and IL-1R1−/− OT-II cells were cotransferred to Rag 1−/− IL-1R1−/− recipients, IL-1 stimulated a marked increase in the antigen-driven response of the WT OT-II cells but had essentially no effect on the KO OT-II cells (Fig. 5B). Thus, cells responding to IL-1 did not enhance the response of cells of the same specificity that were themselves incapable of responding to IL-1.

When IL-1R1−/− OT-II cells were stimulated in WT B6 recipients in the presence of IL-1 plus LPS, the KO T cells showed a relatively modest IL-1-mediated increase in cell expansion compared with similarly treated WT OT-II cells in WT recipients (Fig. 5D), implying that the major effect of IL-1 was on the responding CD4 T cells.

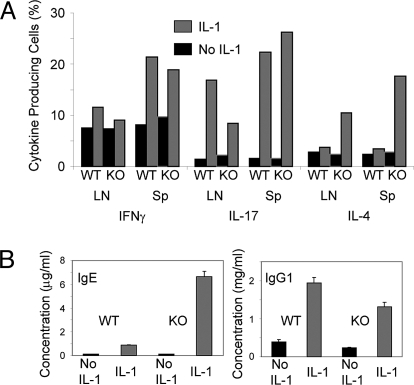

IL-1 Enhances Priming for IL-17 and IL-4 Production by WT T cells Immunized in IL-1R1−/− Recipients.

IL-1 strikingly increased the frequency of IL-17-producing cells, in response to OVA, in both lymph node and spleen among OT-II cells transferred to IL-1R1−/− or WT recipients. IL-1 also increased the frequency of IL-4-producers but only in IL-1R1−/− recipients. The frequency of IFNγ producers was increased as well although more modestly than IL-4- or IL-17-producers (Fig. 6A). A similar analysis was done in the Rag1−/− IL-1R1−/−recipients of OT-II cells. The results were even more dramatic with the IL-1-induced frequency of IL-17 producers in lymph node being ≈20% and of IL-4-producers >40%. In the spleen, IL-17 producers were >40% in the presence of IL-1.

Fig. 6.

IL-1 enhances cytokine, IgE and IgG1 responses. (A) IL-1 augments the differentiation of cytokine-producing cells in OT-II cells primed in IL-1R1−/− recipients. Lymph nodes and spleens from mice of the experiment described in the legend to Fig. 5A were removed 7 days after immunization and the single cell suspensions were stimulated with PMA and ionomycin as described in Materials and Methods. The percentage of IL-4, IFNγ and IL-17-producing cells among the OT-II cells was determined by intracellular staining and FACS analysis of the CD4+, Vα2+, Vβ5+ gated population. (B) IL-1 induces the production of high levels of IgE and IgG1 7 days after priming in IL-1R1−/− mice. Mice from the experiment described in the legend to Fig. 5A were bled 7 days after immunization and the concentrations of serum IgG1, and IgE measured by ELISA.

In IL-1R1−/− recipients of WT OT-II cells immunized with OVA plus LPS, IL-1 caused a >64-fold increase in serum IgE concentration, to 6.6 μg/mL (Fig. 6B), and a 6-fold increase in serum IgG1 concentration.

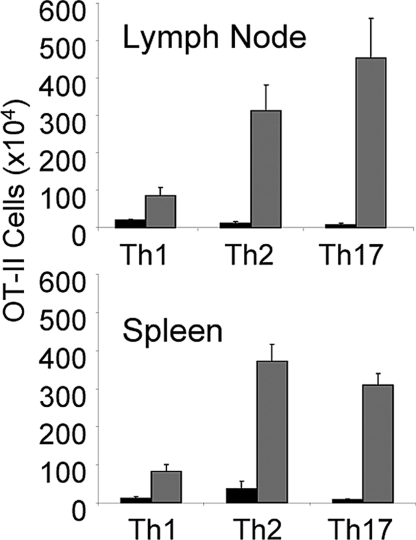

IL-1 Enhances Antigen-Stimulated Proliferation of Th1, Th2 and Th17 Cells.

OT-II cells were primed in vitro under Th1, Th2 and Th17 polarizing conditions and 0.8 (Th17) to 2 × 106 (Th1 and Th2) cells transferred to 1L-1R1−/− Rag1−/− recipients. The mice were then challenged with OVA administered in a miniosmotic pump with or without IL-1.

IL-1 resulted in a markedly greater expansion of the Th2 and Th17 cells. IL-1 also caused an enhanced expansion of Th1 cells (Fig. 7), although the degree of enhancement was less striking than that of the Th2 and Th17 cells. That the cells that did expand under the influence of IL-1 were actually Th1 cells was shown by the finding that 40% or more of these cells produced IFNγ upon stimulation. Thus, IL-1 not only could enhance priming of each cell type but could also enhance response of already differentiated cells.

Fig. 7.

IL-1 enhances the antigen-induced expansion of Th1, Th2, and Th17 cells in vivo. In vitro differentiated Th1, Th2, or Th17 OT-II cells were transferred IP into B6 1L-1R1−/− Rag1−/− mice (0.8 to 2 × 106 per mouse). Seven days later, mice were immunized by implantation of a miniosmotic pump containing 1 mg of ovalbumin and either IL-1β (10 μg) or PBS. After a week, the number of CD4+/Vα2+, Vβ5+ cells in the lymph nodes and spleens was determined as described in Materials and Methods.

IL-1 Accounts for a Portion of the LPS Effect on 5C.C7 Cell Expansion.

B10.A recipients of 5C.C7 cells were challenged with PCC in a miniosmotic pump or s.c. with LPS in the presence or absence of the IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra). In a series of 4 experiments, 5C.C7 cell expansion was diminished to 44% of control by IL-1Ra (95% confidence interval of the estimate was 8% to 70%) (Table 1), indicating that IL-1 is responsible for a large portion of the adjuvant effects of LPS and miniosmotic pumps.

Table 1.

IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra) partially inhibits the adjuvant effects of LPS and miniosmotic pumps

| Exp. | Immuniz. | Tissue | Day after priming | Relative Response in Presence of IL-Ra | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | LPS | Blood | 6 | 0.595 | 0.05 |

| 1 | LPS | Blood | 13 | 0.574 | 0.01 |

| 2 | LPS | Blood | 7 | 0.404 | 0.05 |

| 3 | LPS | LN | 6 | 0.314 | 0.08 |

| 3 | LPS | Spleen | 6 | 0.286 | 0.04 |

| 4 | Pump | LN | 7 | 0.556 | 0.13 |

| 4 | Pump | Spleen | 7 | 0.354 | 0.02 |

| Mean | 0.440 | ||||

| SD | 0.131 | ||||

| 95% | |||||

| Confid. | 0.181 to | ||||

| Interval | 0.699 |

5C.C7/RAG-2−/−/CD45.1 B10.A lymph node cells (5–8 × 105) were transferred IP into B10.A mice. Mice were immunized with PCC (500–1,000 μg) and LPS (25 μg) SC with or without IL-1Ra that was given daily by IP injections for 6–7 days (1.25 mg per injection) or mini-osmotic pumps containing 1 mg PCC with or without IL-1Ra (200 μg) were implanted. Six to 13 days after immunization, the percentage of 5C.C7 cells among the PBMCs or in the lymphoid organs was determined as described in Materials and Methods. The fractional response in the presence of IL-1Ra is shown.

Discussion

IL-1 markedly enhances expansion of T cells stimulated by their cognate antigen. This occurred for primary responses by naïve polyclonal and TCR-transgenic cells, for in vivo-primed TCR transgenic cells and for in vitro-primed Th1, Th2 and Th17 cells. IL-1 also improved the durability of a primary response. No other proinflammatory cytokine we tested (IL-6, TNFα, IL-18 and IL-33) had any significant activity nor did IL-2, IL-4, IL-7, IL-9, IL-15 or IL-21, all known to regulate T cell growth through various mechanisms.

The effect of exogenous IL-1 in increasing CD4 T cell responses to antigenic challenge is particularly notable in view of recent work indicating that alum mediates much of its adjuvant activity through activation of the NLRP3/NALP3 inflammasome with consequent production of IL-1, IL-18 and possibly IL-33 (22). Indeed, antigen-specific antibody responses to immunization with alum as an adjuvant were significantly impaired in mice deficient in NALP3/NLRP3 (22).

In our experiments, the responding T cell was the major target of IL-1 and its response was cell autonomous, in contrast to the report by Khoruts et al. (17). Indeed, CD28−/− OT-II cells showed a robust increase in response to IL-1 plus antigen over that to antigen alone.

IL-1 has been shown to promote the differentiation of naïve CD4 T cells into Th17 cells (9) and to promote expansion of IL-17-secreting memory CD4+ T cells (23). Functional IL-1Rs have been detected on mature Th17 and Th2 cells (24, 25) although their expression on Th1 clones has not been shown (25). It is striking that IL-4 and IL-17 were produced by a significant proportion of WT OT-II cells primed, in the presence of IL-1, in IL-1R1−/− recipients. This result is also in keeping with the known effects of alum in promoting IgE and IgG1 responses (26) and in the very striking increases in IgE and IgG1 we observed 7 days after priming when IL-1 was used in immunizing IL-1R1−/− recipients of WT OT-II cells. This is also consistent with the striking inhibition of these 2 IL-4-dependent Ig classes when antigen is administered in alum to inflammasome-deficient mice (22) and with the important role of IL-1 in regulating Th2 responses during gastrointestinal nematode infection (27). However, IL-1 not only caused a >30-fold increase in expansion of primed Th17 OT-II cells transferred to B6 1L-1R1−/− Rag1−/− recipients upon challenge with OVA and IL-1 and a >10-fold increase in Th2 cells, it also caused a 4–7-fold increase in the expansion of Th1 cells. This is striking in so far as IL-1 receptors have not been detected on Th1 cells (25), although we have observed IL-1 mediated NF-κB activation in Th1 cells.

The continuous administration of IL-1 for 7 days at a dosage that induces blood levels of IL-6 and MCP-1 comparable to those occurring in Listeria monocytogenes infection (unpublished data) may account for the striking effect on CD4 T cells. The substantially lower dose of IL-1 (20-fold) used by Khoruts et al. Because a single IV injection would not produce a sustained blood level (28) and may not have been adequate to provide a direct signal to the responding CD4 T cells throughout the stimulatory process, presumably limiting the IL-1 effect to APC. Furthermore, Snapper and colleagues showed that IL-1R1−/− mice exhibited relatively intact innate cytokine responses and normal T-independent IgM responses to Streptococcus pneumoniae but had deficient CD4 T cell responses (3), suggesting that IL-1 acted directly on CD4 cells.

Although IL-1 induces IL-6 (29) and IL-6 augments the replication and survival of stimulated CD4 T cells both in vitro and in vivo (30), the effect of IL-1 on stimulated CD4 cells does not require IL-6 activity. In a system in which the 5C.C7 donor T cells and the recipients were both IL-6-deficient, an IL-1 effect was obtained.

We failed to detect Foxp3+ cells among naïve OT-II or OT-II IL-1R1−/− cells and the frequency of such cells 2 days after in vivo challenge of OT-II cells, ≈2%, makes it unlikely that IL-1 mediates its function by blocking Tregs.

CFSE analysis indicates that IL-1-mediated increased replication can only account for an ≈2-fold increase in expansion whereas the actual increase in cell expansion was 7- to 8-fold, implying that much of the IL-1 effect must be due to enhanced survival. The precise mechanism by which IL-1 enhances the survival and the proliferation of the stimulated cells is still unknown but activation of MyD88 and of the NF-κB pathway, both of which are engaged by IL-1, promotes proliferation and survival of activated CD4 T cells (31, 32).

IL-1Ra partially inhibited the response of T cells to antigen plus LPS or to antigen delivered by a miniosmotic pump. The failure to obtain complete inhibition may be due to the degree of activity of IL-1Ra and/or its short half life in vivo, but prior reports indicating only partial diminution of immune responses in IL-1 KO mice (5, 33) and upon administration of IL-1Ra into mice with autoimmune diseases (34, 35) imply that IL-1 may play a redundant role in this process. Indeed, NALP3-/NLRP3-deficient mice showed good responses to complete Freund's adjuvant although the adjuvant action of alum was inhibited (22) confirming an earlier observation that anti-IL-1 antibodies inhibited a T cell proliferative response after immunization with an alum adjuvant but not with Freund's complete adjuvant (36).

IL-1's striking proinflammatory effects would seem to preclude its use in most preventive vaccines, particularly in healthy individuals. However, in therapeutic vaccines for tumors or chronic infections, “side effects” might be more easily accepted, suggesting that IL-1 might be used as an adjuvant under controlled conditions. Understanding the molecular basis of IL-1's activity in CD4 T cells will be essential if we are to use T cell-specific members of this pathway as targets of novel adjuvants of limited toxicity or for drugs aimed at suppressing pathological CD4 T cell responses.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

Female mice of the strains specified in SI Materials and Methods were obtained from Taconic Farms and from the Jackson laboratory. Mice were maintained under pathogen-free conditions and were used at 6–8 weeks of age.

Cytokines and Abs.

Recombinant cytokines (as specified in SI Materials and Methods) were purchased from PeproTech and R&D Systems. The gp 61–80 peptide was purchased from American Peptide. Fluorochrome-conjugated Abs (as specified in SI Materials and Methods), were purchased from BD PharMingen. and eBioscience. APC- IAb restricted gp 66–77 tetramer was obtained from the National Institutes of Health Tetramer Core Facility. IL-1Ra (Anakinra) was obtained from the University of Colorado Hospital Pharmacy (Denver, CO).

Generation of Th1, Th2 and Th17 In Vitro.

Lymph node cells from OT-II/RAG-1−/−B6 mice were primed in vitro with irradiated (30 Gy) T-depleted B6 splenocytes and OVA peptide 323–339 under Th1, Th2 or Th17 as specified in the SI Materials and Methods. After 4 days, the cells were washed and rested for a week in IL-2 (100 units/mL) (Th1 and Th2) or in IL-23 (20 ng/mL) (Th17). A second round of identical stimulation and rest period were performed.

Tetramer Staining.

Lymph node or spleen cells (2 × 106) were incubated for 30 min. at 37C in 0.2 mL of culture medium with APC conjugated IAb-restricted gp66–77 tetramer (2 μg/mL) followed by staining at 4C for 30 min. with FITC anti-CD44, PE anti-Vα2 and PE Cy7 anti-CD4. Cells were washed in PBS with 0.1%BSA and analyzed with a BD LSRII, using FlowJo software (Tree Star).

Intracellular Cytokine Staining.

Spleen and lymph node cells were stimulated with ionomycin and phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), fixed, permeabilized and stained as specified in SI Materials and Methods. The stained cells were analyzed with a BD LSRII, using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc).

In Vivo Priming of Adoptively Transferred Transgenic Cells.

Unless otherwise specified, cells (0.5 to 2 × 106) from lymph nodes of transgenic donor mice were injected i.p. (IP) into normal syngeneic B10.A or C57BL/6 mice (3–5 mice for each experimental group). In the experiments, the OT-II lymph node cells were enriched for CD4 cells by passage over T enrichment column (R&D Systems) before transfer to the recipient C57BL/6 mice. In some experiments, mice were immunized 7–10 days later by implantation of miniosmotic pumps (Durect) containing 10–1,000 μg of antigen (PCC or OVA) (Sigma–Aldrich) with or without cytokine (10 μg) in HBSS for 7 days. In other experiments, mice were immunized s.c. or in the foot pads (FP) by injection of 500-1000 μg of antigen (PCC or OVA) with or without 25 μg of LPS (Escherichia coli 0111:B4; InvivoGen). Some of the s.c.- or FP-immunized mice were given IL-1β (10 μg) that was delivered for 7 days by miniosmotic pumps that were implanted in the mice at the day of immunization.

Monitoring Donor CD4 Transgenic Cells.

At specified times, the percentage of 5C.C7 donor cells among the PBMCs in the blood or in the single cell suspensions of the lymphoid organs was determined by staining with FITC-anti-CD45.1, PE-anti-Vβ3, APC- anti-CD45.2 and PE Cy7- anti-CD4 Abs in the presence of anti-FcγRII/III Abs (2.4G2) followed by flow cytometric analysis with a FACSCalibur and CellQuest software and identification of the CD4+/Vβ3+/CD45.1+/CD45.2− cells.

The percentage of the OT-II donor cells in the blood samples and the lymphoid organs of the recipient mice was determined by staining with FITC-anti-Vβ5, PE-anti-Vα2 and APC-anti-CD4 Abs and the identification of the CD4+/Vα2++/Vβ5+ Tg cells. The number of 5C.C7 or OT-II cells in the lymphoid organs was determined by multiplying the cell number in the organ by the fraction of Tg cells in that organ.

Cell Division Analysis.

Lymph node cells from 5C.C7/RAG-2−/−/CD45.1 mice were labeled with CFSE as described in ref. 30. The CFSE labeled cells were injected IP into syngeneic B10.A mice. After 7 days, the recipient mice were implanted with miniosmotic pumps containing PCC (1 mg) with or without IL-1β (10 μg). Two, 3, or 4 days later, lymph nodes and spleens were removed, stained with PE-anti-Vβ3, APC-anti-CD45.1 and PE Cy7-anti-CD4. The percentage of cells in various CFSE peaks among CD4+/Vβ3+/CD45.1+ population was determined by analysis with a FACSCalibur and CellQuest software.

Measurement of Serum OVA-Specific IgG1 Antibodies.

The relative concentration of IgG1 anti-OVA in the sera was determined by sandwich Elisa on OVA coated Immulon plates (Thermo Scientific) with HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG1 Abs (Southern Biotechnology).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Dr. George Punkosdy, Laboratory of Immunology/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, for his generous help with the LCMV peptide immunization and tetramer staining. This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0902745106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Joffre O, Nolte MA, Spörri R, Reis e Sousa C. Inflammatory signals in dendritic cell activation and the induction of adaptive immunity. Immunol Rev. 2009;227:234–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dinarello CA. Interleukin-1 family of ligands and receptors. In: Paul WE, editor. Fundamental Immunology. 6th Ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen Q, Sen G, Snapper CM. Endogenous IL-1R1 signaling is critical for cognate CD4+ T cell help for induction of in vivo type 1 and type 2 antipolysaccharide and antiprotein Ig isotype responses to intact Streptococcus pneumoniae, but not to a soluble pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. J Immunol. 2006;177:6044–6051. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.6044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zwijnenburg PJ, et al. IL-1 receptor type 1 gene-deficient mice demonstrate an impaired host defense against pneumococcal meningitis. J Immunol. 2003;170:4724–4730. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.9.4724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmitz N, Kurrer M, Bachmann MF, Kopf M. Interleukin-1 is responsible for acute lung immunopathology but increases survival of respiratory influenza virus infection. J Virol. 2005;79:6441–6448. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.10.6441-6448.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koziczak-Holbro M, et al. IRAK-4 kinase activity is required for interleukin-1 (IL-1) receptor- and toll-like receptor 7-mediated signaling and gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:13552–13560. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700548200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ku CL, et al. Selective predisposition to bacterial infections in IRAK-4 deficient children: IRAK-4 dependent TLRs are otherwise redundant in protective immunity. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2407–2422. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fleischmann RM, et al. Anakinra, a recombinant human interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (r-metHuIL-1Ra), in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A large, international, multicenter, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:927–934. doi: 10.1002/art.10870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Acosta-Rodriguez EV, Napolitani G, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. Interleukins 1beta and 6 but not transforming growth factor-beta are essential for the differentiation of interleukin 17-producing human T helper cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:942–949. doi: 10.1038/ni1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aujla SJ, et al. IL-22 mediates mucosal host defense against Gram-negative bacterial pneumonia. Nat Med. 2008;14:275–281. doi: 10.1038/nm1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung DR, et al. CD4+ T cells mediate abscess formation in intra-abdominal sepsis by an IL-17-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 2003;170:1958–1963. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.4.1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelly MN, et al. Interleukin-17/interleukin-17 receptor-mediated signaling is important for generation of an optimal polymorphonuclear response against Toxoplasma gondii infection. Infect Immun. 2005;73:617–621. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.1.617-621.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang W, Na L, Fidel PL, Schwarzenberger P. Requirement of interleukin-17A for systemic anti-Candida albicans host defense in mice. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:624–631. doi: 10.1086/422329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khader SA, et al. IL-23 and IL-17 in the establishment of protective pulmonary CD4+ T cell responses after vaccination and during Mycobacterium tuberculosis challenge. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:369–377. doi: 10.1038/ni1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Milner JD, et al. Impaired T(H)17 cell differentiation in subjects with autosomal dominant hyper-IgE syndrome. Nature. 2008;452:773–776. doi: 10.1038/nature06764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pape KA, Khoruts A, Mondino A, Jenkins MK. Inflammatory cytokines enhance the in vivo clonal expansion and differentiation of antigen-activated CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 1997;159:591–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khoruts A, Osness RE, Jenkins MK. IL-1 acts on antigen-presenting cells to enhance the in vivo proliferation of antigen-stimulated naive CD4 T cells via a CD28-dependent mechanism that does not involve increased expression of CD28 ligands. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:1085–1090. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo Z, et al. Fas ligation induces IL-1beta-dependent maturation and IL-1beta-independent survival of dendritic cells: Different roles of ERK and NF-kappaB signaling pathways. Blood. 2003;102:4441–4447. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luft T, et al. IL-1 beta enhances CD40 ligand-mediated cytokine secretion by human dendritic cells (DC): A mechanism for T cell-independent DC activation. J Immunol. 2002;168:713–722. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.2.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wesa A, Galy A Increased production of proinflammatory cytokines and enhanced T cell responses after activation of human dendritic cells with IL-1 and CD40 ligand. BMC Immunol. 2002;3:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-3-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Varga SM, Welsh RM. Detection of a high frequency of virus-specific CD4+ T cells during acute infection with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. J Immunol. 1998;161:3215–3218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eisenbarth SC, et al. Crucial role for the Nalp3 inflammasome in the immunostimulatory properties of aluminium adjuvants. Nature. 2008;453:1122–1126. doi: 10.1038/nature06939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rao DA, Tracey KJ, Pober JS. IL-1α and IL-1β are endogenous mediators linking cell injury to the adaptive alloimmune response. J Immunol. 2007;179:6536–6546. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.10.6536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McKean DJ, et al. Murine T helper cell-2 lymphocytes express type I and type II IL-1 receptors, but only the type I receptor mediates costimulatory activity. J Immunol. 1993;151:3500–3510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor-Robinson AW, Phillips RS. Expression of the IL-1 receptor discriminates Th2 from Th1 cloned CD4+ T cells specific for Plasmodium chabaudi. Immunology. 1994;81:216–221. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lindblad EB. Aluminium compounds for use in vaccines. Immunol Cell Biol. 2004;82:497–505. doi: 10.1111/j.0818-9641.2004.01286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Helmby H, Grencis R. Interleukin 1 plays a major role in the development of Th2-mediated immunity. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:3674–3681. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Newton RC, Uhl J, Covington M, Back O. The distribution and clearance of radiolabeled human interleukin-1 beta in mice. Lymphokine Res. 1988;7:207–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kishimoto T. The biology of interleukin-6. Blood. 1989;74:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rochman I, Paul WE, Ben-Sasson SZ. IL-6 increases primed cell expansion and survival. J Immunol. 2005;174:4761–4767. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.4761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gelman AE, et al. The adaptor molecule MyD88 activates PI-3 kinase signaling in CD4+ T cells and enables CpG oligodeoxynucleotide-mediated costimulation. Immunity. 2006;25:783–793. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khoshnan A, et al. The NF-{kappa}B cascade is important in Bcl-xL expression and for the anti-apoptotic effects of the CD28 receptor in primary human CD4+ lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2000;165:1743–1754. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.4.1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmitz N, Kurrer M, Kopf M. The IL-1 receptor 1 is critical for Th2 cell type airway immune responses in a mild but not in a more severe asthma model. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:991–1000. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Badovinac V, Mostarica-Stojkovic M, Dinarello CA, Stosic-Grujicic S. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist suppresses experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) in rats by influencing the activation and proliferation of encephalitogenic cells. J Neuroimmunol. 1998;85:87–95. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(98)00020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bendele A, et al. Effects of interleukin 1 receptor antagonist alone and in combination with methotrexate in adjuvant arthritic rats. J Rheumatol. 1999;26:1225–1229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grun JL, Maurer PH. Different T helper cell subsets elicited in mice utilizing two different adjuvant vehicles: the role of endogenous interleukin 1 in proliferative responses. Cell Immunol. 1989;121:134–145. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(89)90011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.