Abstract

NFAT transcription factors are highly phosphorylated proteins residing in the cytoplasm of resting cells. Upon dephosphorylation by the phosphatase calcineurin, NFAT proteins translocate to the nucleus, where they orchestrate developmental and activation programs in diverse cell types. NFAT is rephosphorylated and inactivated through the concerted action of at least 3 different kinases: CK1, GSK-3, and DYRK. The major docking sites for calcineurin and CK1 are strongly conserved throughout vertebrate evolution, and conversion of either the calcineurin docking site to a high-affinity version or the CK1 docking site to a low-affinity version results in generation of hyperactivable NFAT proteins that are still fully responsive to stimulation. In this study, we generated transgenic mice expressing hyperactivable versions of NFAT1 from the ROSA26 locus. We show that hyperactivable NFAT increases the expression of NFAT-dependent cytokines by differentiated T cells as expected, but exerts unexpected signal-dependent effects during T cell differentiation in the thymus, and is progressively deleterious for the development of B cells from hematopoietic stem cells. Moreover, progressively hyperactivable versions of NFAT1 are increasingly deleterious for embryonic development, particularly when normal embryos are also present in utero. Forced expression of hyperactivable NFAT1 in the developing embryo leads to mosaic expression in many tissues, and the hyperactivable proteins are barely tolerated in organs such as brain, and cardiac and skeletal muscle. Our results highlight the need for balanced Ca/NFAT signaling in hematopoietic stem cells and progenitor cells of the developing embryo, and emphasize the evolutionary importance of kinase and phosphatase docking sites in preventing inappropriate activation of NFAT.

The activities of many signaling proteins and transcription factors are tightly regulated by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. Protein kinases and phosphatases bind to specific docking sites on these intracellular proteins to allow their activation or inactivation at the appropriate location and time. A well-studied example of a transcription factor regulated in this fashion is nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) (1–3). In resting cells, NFAT proteins are highly phosphorylated and reside in the cytoplasm; upon cell activation, they are dephosphorylated by the calcium/calmodulin-dependent phosphatase calcineurin and translocate to the nucleus. NFAT transcription factors play a key role in orchestrating diverse developmental programs, including those of the immune, central nervous, cardiovascular, and musculoskeletal systems (4–11). NFAT also is implicated in maintaining the quiescent state of stem cells in the skin (12).

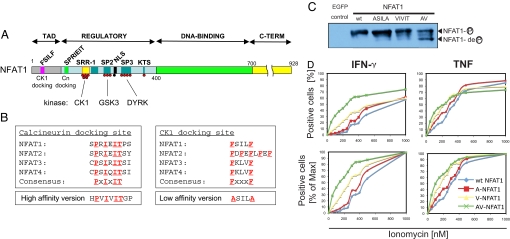

NFAT activation is initiated by dephosphorylation of the NFAT regulatory domain, a conserved 300-amino acid region located N-terminal to the DNA-binding domain (Fig. 1A) (2, 13). The phosphorylated residues (serines) in this domain are distributed among several classes of conserved serine-rich sequence motifs (14, 15), and their phosphorylation status is maintained by the concerted action of at least 3 families of kinases: CK1, GSK3, and DYRK (16–20). We have shown previously that enzyme–substrate docking interactions are required for efficient dephosphorylation of the NFAT1 regulatory domain by calcineurin (21, 22) and for efficient phosphorylation of the SRR-1 motif by CK1 (20). The major docking sites for calcineurin and CK1 are located near the N terminus of NFAT (Fig. 1A), are conserved among NFAT proteins, and fit the consensus sequences PxIxIT and FxxxF, respectively (20–22) (Fig. 1B). Substitution of the calcineurin docking sequence, SPRIEIT, with its high-affinity variant, HPVIVIT, and substitution of the CK1 docking sequence, FxxxF, with a low-affinity version, ASILA, both result in partial nuclear localization of NFAT1 in a manner that is still inhibited by CsA (20, 21). Thus, these mutant NFAT1 proteins are not constitutively (i.e., irreversibly) activated, but are hypereactive relative to wild-type NFAT1 in that they remain responsive to stimulation.

Fig. 1.

Conservation of kinase and phosphatase docking sites on NFAT proteins and analysis of hyperactivable NFAT1 mutants. (A) Schematic overview of NFAT1. TAD indicates transactivation domain; Cn, calcineurin; NLS, nuclear localization signal. (B) Conservation of calcineurin and CK1 docking sites in NFAT proteins. Consensus motifs and modified motifs with altered affinities (in NFAT1) are shown. (C) HEK293 cells were transduced with retroviral expression plasmids encoding EGFP or HA-tagged wild-type (wt) NFAT1, A-NFAT1, V-NFAT1 or AV-NFAT1, and NFAT1 phosphorylation status was assessed by immunoblotting with an anti-HA antibody. (D) CD8 T cells from NFAT1−/− mice were retrovirally transduced to express wt or hyperactivable NFAT1, then left unstimulated or stimulated with PMA and increasing concentrations of ionomycin for 4 h. Results are represented both as the percentage of positive cells (top graphs) and normalized to set the maximum number of positive cells in each series to 100% to show the shift in the dose-response curve more clearly (bottom graphs).

Here, we have examined the effects of increased Ca/NFAT signaling by generating transgenic mice conditionally expressing different hyperactivable mutants of NFAT1 from the ROSA26 (R26) locus. We demonstrate that progressively hyperactivable NFAT1 proteins are increasingly deleterious during early embryonic development and the development of hematopoietic stem cells into T and B cell lineages. We also show that low-level ectopic expression of hyperactivable NFAT1 in the early embryo leads to mosaicism in many tissues and is barely tolerated in organs such as brain, heart, and skeletal muscle, where NFAT function is known to be essential. In contrast, expression of hyperactivable NFAT1 proteins at a late stage of T cell differentiation is well tolerated and leads to a hyperresponsive phenotype in peripheral T cells. Taken together, our data provide strong evidence for the necessity of balanced Ca/NFAT signaling in progenitor cells of the developing embryo as well as in lymphocyte development, and shed new light on the importance of the evolutionary conservation of phosphatase and kinase docking sites in preventing inappropriate activation of the Ca/NFAT signaling pathway.

Results

Mutation of Conserved Docking Sites for Calcineurin and CK1 Makes NFAT Hyperactivable.

To assess the biological consequences of increased NFAT signaling in different tissues, we generated hyperactivable mutants of NFAT1. Previous studies have used NFAT proteins bearing alanine substitutions in phosphorylated serines in the regulatory domain, which are constitutively and irreversibly active (9, 15, 23). Instead, we chose to generate hyperactivable, stimulus-responsive versions of NFAT1 by mutating the CK1 and calcineurin docking sites to lower and higher affinities, respectively. The conserved CK1 docking site (FSILF in NFAT1) was altered to the low-affinity docking version ASILA (20), yielding ASILA-NFAT1 (abbreviated A-NFAT1); the conserved calcineurin docking site (SPRIEITPS in NFAT1) was altered to the high-affinity version HPVIVITGP (22), yielding VIVIT-NFAT1 (abbreviated V-NFAT1); and both mutations were combined to yield a protein expected to be even more responsive to stimulation (ASILA-VIVIT-NFAT1, abbreviated AV-NFAT1). When tested by transient transfection into HEK293 cells, the hyperactivable mutants were increasingly dephosphorylated relative to wild-type NFAT1, in the expected order A-NFAT1 ≈ V-NFAT1 < AV-NFAT1 (Fig. 1C). We confirmed that the mutants were hyperactivable, not constitutively active, by retrovirally expressing them in CD8 T cells from NFAT1−/− mice (24) (Fig. 1D, Fig. S1). When stimulated with PMA plus increasing concentrations of the calcium ionophore ionomycin, T cells expressing the hyperactivable NFAT1 mutants exhibited a clear shift, relative to cells expressing wild-type NFAT1, in their dose–response curve for expression of the cytokines IFN-γ and TNF, with the order of responsiveness being AV > V > A > wild type. Cytokine expression was strictly dependent upon stimulation and was fully inhibited by the calcineurin inhibitor cyclosporine A (CsA).

Hyperactivable NFAT1 Proteins Are Deleterious During Early Embryonic Development.

To examine the effects of expressing the hyperactivable proteins in different cellular lineages in vivo, we generated transgenic mice conditionally expressing V-NFAT1 and AV-NFAT1 from the ROSA26 (R26) locus (25) (Fig. S2). In these mice, one or both alleles of the ROSA26 gene are replaced by a floxed cassette containing a neomycin-resistance (NeoR) gene and 3 tandem transcriptional stop sites (abbreviated STOPflox), followed immediately by the hyperactivable V-NFAT1 or AV-NFAT1 transgene. Expression of the hyperactivable proteins is controlled by Cre-mediated excision of the STOPflox cassette, and it can be monitored at a single-cell level by concomitant expression of EGFP from an internal ribosome entry site (IRES) (26). As a control, we used R26STOPflox-YFP reporter mice (27).

As a first step in the analysis, male mice of all 3 lines were bred to female CMV-Cre transgenic mice (deleter mice) (28). The Cre transgene in this strain is under transcriptional control of a human cytomegalovirus minimal promoter and is expressed transiently during early embryogenesis (before implantation), leading to deletion of loxP-flanked gene segments in all tissues, including germ cells (Fig. S3). Because the Cre transgene in this strain is X-linked (28), female CMV-Cre transgenic mice were used for all crosses; this avoids the problem that the paternal X chromosome is inactivated before implantation, reactivated in blastocysts, and randomly inactivated in somatic tissues thereafter (29–33). In contrast, offspring of female CMV-Cre transgenic mice carry the Cre transgene on their maternal X chromosome, which is consistently active before blastocyst implanation (29, 30).

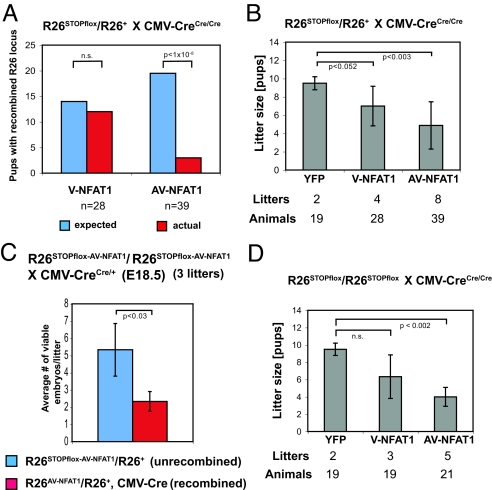

Unexpectedly, we found that widespread expression of AV-NFAT1 in vivo was deleterious to embryonic development, with V-NFAT1 having a lesser effect. We bred heterozygous male R26STOPflox-V-NFAT1/R26+ or R26STOPflox-AV-NFAT1/R26+ mice to homozygous female CMV-CreCre/Cre (deleter) mice. Mendelian genetics predict that 50% of the offspring would have the genotype R26V-NFAT1/R26+, CMV-Cre or R26AV-NFAT1/R26+, CMV-Cre [i.e., possess 1 copy of the wild-type ROSA26 allele (R26+), 1 copy of the expressible version of the hyperactivable NFAT1 in which the NeoR-STOP cassette has been deleted, and 1 copy of the Cre transgene], whereas the other 50% would have the genotype R26+/R26+, CMV-Cre (Fig. S4A). Instead, we observed an increasing competitive disadvantage in utero for pups capable of expressing hyperactivable NFAT1 (Fig. 2 A and B). Instead of the 50% expected, ≈43% of the offspring of R26STOPflox-V-NFAT1/R26+× CMV-CreCre/Cre breedings possessed an R26V-NFAT1 allele, and fewer than 10% of the offspring of R26STOPflox-AV-NFAT1/R26+× CMV-CreCre/Cre breedings possessed an R26AV-NFAT1 allele capable of driving expression of hyperactivable NFAT1 (Fig. 2A). In line with these observations, litter sizes decreased progressively in the offspring of these crosses (R26YFP> R26V-NFAT1 > R26AV-NFAT1; Fig. 2B), emphasizing the dependence of the deleterious effect on the degree of hyperactivability of the transgenic proteins.

Fig. 2.

Expression of hyperactivable NFAT1 is deleterious during embryonic development. (A) Expected and actually detected frequencies of the recombined (NeoR-STOP cassette deleted) R26 transgenes in offspring of different R26STOPflox/R26+ × CMV-CreCre/Cre crosses. P values were determined using a standard χ2 test. n.s., not significant. (B) Litter sizes of different R26STOPflox/R26+ × CMV-CreCre/Cre crosses, P values were determined using a standard Student's t test. (C) Frequency of the unrecombined (R26STOPflox-AV-NFAT1/R26+) and recombined (R26AV-NFAT1/R26+, CMV-Cre) R26 allele at embryonic day 18.5 (E18.5). Male R26STOPflox-AV-NFAT1/R26STOPflox-AV-NFAT1 mice were crossed with female CMV-CreCre/+ mice. Pregnant females were sacrificed on E18.5 and embryos were assessed for viability and genotype. The average values for viable embryos from 3 litters with standard deviations are shown. P values were determined using a standard Student's t test. (D) Litter sizes of different R26STOPflox/R26STOPflox × CMV-CreCre/Cre crosses. P values were determined using a standard Student's t test.

To further delineate the effects of hyperactivable NFAT1 in utero, we performed the crosses in the opposite direction and did timed pregnancy experiments. We bred homozygous male R26STOPflox-AV-NFAT1/R26STOPflox-AV-NFAT1 mice to heterozygous female CMV-CreCre/+ mice and analyzed the offspring of the pregnant females at embryonic day 18.5. Again, 50% of the offspring were expected to express Cre and delete the NeoR-STOP cassette, therefore becoming capable of expressing the hyperactivable NFAT1 (genotype R26AV-NFAT1/R26+). However, the average fraction of viable embryonic day 18.5 embryos carrying the expressible AV-NFAT1 transgene was again significantly lower than expected from Mendelian genetics (50% expected, 30% observed), and multiple dead, involuted embryos were seen (Fig. 2C and S4B). These results indicate that mice globally expressing hyperactivable V-NFAT1 or AV-NFAT1 have a survival disadvantage and are not competitive with their littermate controls in utero. This is not due to deleterious effects of expression of the Cre transgene (34) (see SI Text). We monitored germ line transmission of the hyperactivable NFAT1 alleles by breeding mosaic animals carrying the recombined R26 locus (R26V-NFAT1/R26+, CMV-Cre or R26AV-NFAT1/R26+, CMV-Cre) to wild-type C57BL/6 mice (Fig. S5). The expressed V-NFAT1 transgene was transmitted to offspring at a significantly lower frequency than expected (50% expected, 26% observed), and the recombined AV-NFAT1 allele was never transmitted through the germ line. Thus, there is efficient germ-line selection against hyperactivable NFAT1 proteins in a manner that correlates with their degree of hyperresponsiveness.

Expression of Hyperactivable NFAT1 Leads to Mosaicism in Many Tissues and Is Not Tolerated in Brain, Heart, and Skeletal Muscle.

We attempted to force expression of hyperactivable NFAT1 by breeding homozygous R26V-NFAT1 or R26AV-NFAT1 mice to homozygous CMV-Cre mice. All of the offspring of these crosses are expected to possess the STOPflox cassette-deleted R26V-NFAT1 or R26AV-NFAT1 allele, and so should be capable of expressing the hyperactivable NFAT1. The crosses yielded live offspring that appeared phenotypically normal. Consistent with the deleterious effects documented above, however, litter sizes in these breedings were increasingly compromised compared with litters bearing the expressible R26YFP transgene (Fig. 2D).

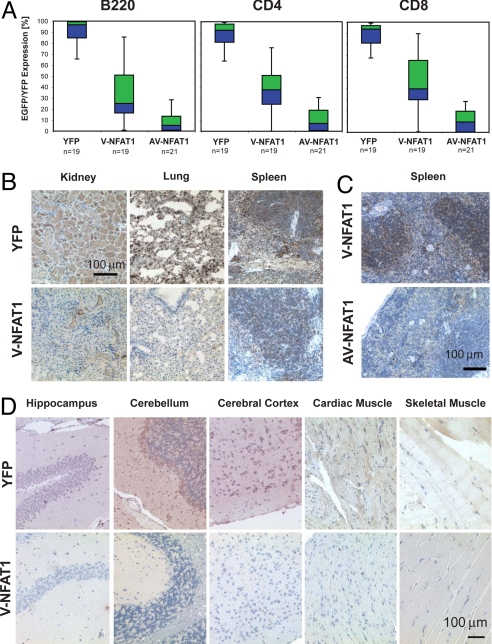

Remarkably, expression of hyperactivable NFAT1 was mosaic in many tissues of surviving R26V- or AV-NFAT1/R26+, CMV-Cre mice, and it seemed not to be tolerated in others. Circulating T and B cells showed increasingly mosaic expression of hyperactivable V-NFAT1 or AV-NFAT1, as judged by expression of the linked EGFP (Fig. 3A; representative primary data are shown in Fig. S6). Breeding of homozygous R26STOPflox-YFP/R26STOPflox-YFP control mice to homozygous CMV-CreCre/Cre mice resulted in stop cassette excision and transgene expression in close to 100% of T and B cells in the vast majority of analyzed R26YFP/R26+, CMV-Cre animals (Fig. 3A, left bars in each graph; median, 92.2–96.7%; n = 19). In contrast, R26V-NFAT1/R26+, CMV-Cre mice were highly mosaic, exhibiting transgene expression in 0.15–89.6% of T and B cells (median, 25.2–39.5%; n = 19), and R26AV-NFAT1/R26+, CMV-Cre mice showed transgene expression in only 0–30.8% of T and B cells (median, 5.3–9.4%; n = 21; Fig. 3A and Fig. S6). Again, therefore, the degree of mosaicism correlated with the degree of hyperactivability of the transgenic NFAT1 proteins.

Fig. 3.

Mosaicism in mice expressing hyperactivable NFAT1 early in embryonic development. (A) Mosaicism in B and T lymphocytes from 8–12 wk old mice expressing different R26 transgenes. Peripheral blood from R26YFP/R26+, CMV-Cre (n = 19); R26V-NFAT1/R26+, CMV-Cre (n = 19) and R26AV-NFAT1/R26+, CMV-Cre (n = 21) transgenic mice was drawn from tail veins and analyzed by flow cytometry. The levels of IRES-EGFP expression in B220+ B lymphocytes, CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes are shown as box-and-whisker diagrams (lower whisker: first quartile, blue box: second quartile, green box: third quartile, upper whisker: fourth quartile, line separating blue and green box: median). (B–D) Immunohistochemistry for EGFP on different tissues from R26YFP/R26+, CMV-Cre; R26V-NFAT1/R26+, CMV-Cre and R26AV-NFAT1/R26+, CMV-Cre transgenic mice. Size bars measure 100 μm as indicated. Tissue sections were counterstained with hematoxylin.

We subsequently assessed the level of transgene expression in different tissues by immunohistochemistry. EGFP expression was detected in kidneys, lung, and spleens of R26V-NFAT1/R26+, CMV-Cre and R26AV-NFAT1/R26+, CMV-Cre mice, with staining generally being more pronounced and involving a larger fraction of cells in V-NFAT1-expressing relative to AV-NFAT1-expressing mice (Fig. 3 B and C). Even in R26V-NFAT1/R26+, CMV-Cre mice, however, there was a notable absence of EGFP staining in brain, heart, and skeletal muscle, suggesting that cells expressing even the less-hyperactivable V-NFAT1 protein were not competitive in populating these organs (Fig. 3D). We confirmed that EGFP expression was tightly linked to expression of hyperactivable NFAT1 from the ROSA26 locus (see SI Text and Fig. S7).

Signal-Dependent Effects of Hyperactivable NFAT1 on T Cell Development in the Thymus.

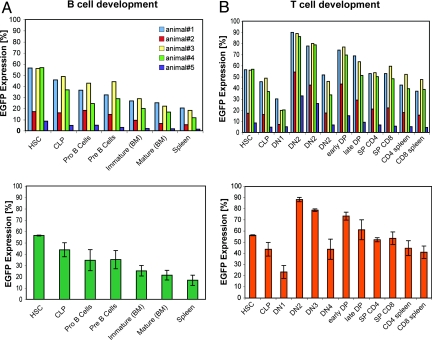

We further investigated the effect of AV-NFAT1 on hematopoietic stem cell differentiation down the T and B cell lineages by monitoring the extent of mosaicism in different precursor populations of R26AV-NFAT1/R26+, CMV-Cre mice. We chose mice expressing different levels of EGFP in peripheral B and T cell populations, then analyzed bone marrow cells and thymocytes by flow cytometry for EGFP expression in hematopoietic stem cells, common lymphocyte precursors, and cells at different stages of B and T cell differentiation. The range of EGFP expression in hematopoietic stem cells was 8.6–56.7% (n = 5). In all animals, the fraction of cells expressing AV-NFAT1 declined gradually from hematopoietic stem cells to mature B lymphocytes in the B cell lineage (Fig. 4A), with expression being ≈3 times higher in the earliest progenitor populations. In contrast, in the T cell lineage, a similar gradual decline of AV-NFAT1 expression was overlaid by peaks corresponding to the expression of the pre-TCR (DN1-to-DN2 transition) and the TCR (DN4-to-DP transition; Fig. 4B) (35). These results strongly suggest that expression of hyperactivable NFAT1 in developing thymocytes modulates the strength of pre-TCR and TCR signaling so as to affect the proliferation and/or survival of T cells making these transitions.

Fig. 4.

Effects of expression of hyperactivable NFAT1 on B and T cell development. (A) (Upper) FACS analysis of different progenitor populations of B cell differentiation for EGFP (AV-NFAT1) expression in 5 different mosaic AV-NFAT1 mice (R26AV-NFAT1/R26+, CMV-Cre). Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), common lymphoid progenitors (CLPs), pro-B cells, pre-B cells, immature B cells, mature B cells (bone marrow), and splenic B cells are shown. (Lower) Mean values and SDs for animals 1, 3, and 4, which exhibited comparable levels of mosaicism. (B) (Upper) HSCs, CLPs, double-negative thymocytes 1 (DN1), DN2, DN3, DN4, early double-positive thymoctes (DPs), late DPs, and single-positives (SPs) are shown. (Lower) Mean values and SDs for animals 1, 3, and 4.

Expression of Hyperactivable NFAT1 at a Late Stage of T Cell Differentiation Is Well Tolerated and Leads to a Hyperresponsive Phenotype.

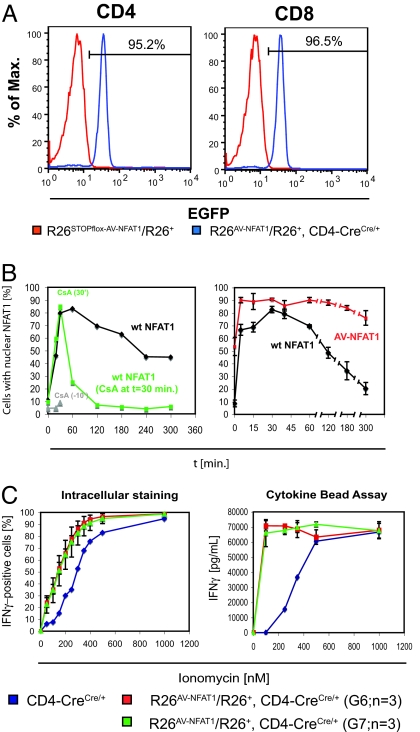

To evaluate the effects of hyperactivable NFAT1 at a late stage of differentiation, we bred the R26-transgenic mice to CD4-Cre mice (36). These mice express the Cre recombinase under control of the CD4 promoter; thus, Cre is expressed beginning at the late “double-positive” stage of thymocyte differentiation, when both CD4 and CD8 are expressed, resulting in efficient excision of floxed DNA segments in all peripheral T cells. More than 95% of peripheral CD4 and CD8 T cells from these mice were EGFP+, indicating that there was no selection against expression of the hyperactivable NFAT1 transgenes at the double-positive stage (Fig. 5A). As expected from earlier retroviral transduction experiments (Fig. 1D), T cells from the mice showed significant hyperresponsiveness to stimulation, as assessed by accelerated nuclear translocation and delayed nuclear export of NFAT (Fig. 5B), as well as substantially increased cytokine expression upon stimulation with low concentrations of stimulus (Fig. 5C). We took advantage of the uniform expression to document that in these T cells, the expression levels of hyperactivable NFAT1 from the ROSA26 locus were substantially lower than those of endogenous NFAT1 (Fig. S8). Thus, the observed effects are due to hyperresponsiveness of the mutant proteins rather than mere overexpression.

Fig. 5.

Effects of expression of hyperactivable NFAT1 at a late stage of T cell differentiation. (A) FACS analysis of CD4 and CD8 T cells from R26AV-NFAT1/R26+, CD4-Cre transgenic mice for EGFP expression (blue line). R26STOPflox-AV-NFAT1/R26+ mice were used as negative controls. (B) NFAT1 translocation assay for endogenous NFAT1 and AV-NFAT1. CD8 T cells were isolated from a C57BL/6 wild-type mouse and an R26AV-NFAT1/R26+, CD4-Cre mouse. Cells were expanded in IL-2, collected on day 5, and stimulated for various time intervals with 10 nM PMA and 1 μM ionomycin (black and red curves; Right). To assess the effects of calcineurin inhibition, 1 μM CsA was added either 10 min before stimulation (gray curve; Left) or 30 min after stimulation (green curve; Left). (C) IFN-γ production in CD8 T cells from R26AV-NFAT1/R26+, CD4-Cre transgenic mice. Cells from 6 R26AV-NFAT1/R26+, CD4-Cre transgenic mice (3 G6, 3 G7; G6 and G7 are 2 different clones of targeted ES cells that have been used for blastocyst injection) were isolated and expanded in IL-2. On day 5, cells were stimulated with 10 nM PMA, and various concentrations of ionomycin and IFN-γ production were assessed by using intracellular cytokine staining and flow cytometry (Left) or using a cytokine bead assay to determine the accumulated IFN-γ in the supernatant (Right) Identically treated CD8 T cells from CD4-Cre mice were used as controls. Each value represents the mean ± SD.

Discussion

To summarize, we have shown that low-level ectopic expression of hyperactivable NFAT1 proteins has severe effects on progenitor cell function during embryonic and hematopoietic development in the mouse. In the first generation, when R26V-NFAT1/R26+ or R26AV-NFAT1/R26+ mice are bred to CMV-CreCre/Cre mice, there is reduced representation of offspring that express the hyperactivable transgene (Fig. 2). If, instead, global expression of hyperactivable NFAT1 is forced by breeding homozygous mice, the tissues of surviving progeny are variably mosaic for transgene expression, implying strong counterselection against developing transgene-positive cells (Fig. 3).

Because Cre expression in the CMV-Cre mouse occurs before implantation (28), the mosaic expression of hyperactivable NFAT1 in adult tissues of the surviving mice implies that Cre expression is transient, and that progenitor cells that escape the early wave of Cre-mediated deletion and therefore lack expression of hyperactivable NFAT1 have a competitive advantage over cells expressing the hyperactivable protein (Fig. S9). Notably, the extent of this advantage correlates with the degree of hyperactivability of the NFAT1 protein. It is striking that the tissues that appear least tolerant of forced expression of hyperactivable NFAT1—brain, heart, and skeletal muscle—are prominent among those in which NFAT is known to be crucial for development and function (4–11). Our results also are consistent with a previous systematic analysis of physiological calcineurin substrates in yeast (37). The docking affinities of these substates for calcineurin ranged from 15 to 250 μM; an engineered inappropriate increase in the affinity of one such substrate, Crz1, improved yeast growth under high-salt conditions but was deleterious under conditions of growth at high pH (37). Likewise, the hyperactivable NFAT1 that we have generated appears to be deleterious during embryogenesis but advantageous in terms of increasing cytokine production by cultured T cells.

During lymphocyte development from hematopoietic stem cells to terminally differentiated B and T cells, we observed a gradual decline of the expression of hyperactivable NFAT1 through different progenitor cell populations. This is most likely due to a mild inability of the AV-NFAT1-expressing cell populations to compete with cells in which the hyperactivable protein is not expressed. These findings are consistent with a previous report showing that as hematopoietic stem cells begin to differentiate, expression of all NFAT family members is downregulated (38, 39); in contrast, hyperactivable NFAT1 proteins expressed from the R26 locus would not be downregulated, and progenitor cells expressing these proteins, even at low levels, would display inappropriately sustained NFAT activity, potentially conferring a competitive disadvantage on those cell populations. NFAT1 has been shown to repress expression of the G0/G1 checkpoint kinase cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (CDK4) (40). Sustained expression of AV-NFAT1 from the R26 locus might thus lead to continuous repression of CDK4, which could at least in part explain the observed inability to compete of the AV-NFAT1-expressing cell populations. This consideration also could account for the peaks observed during T cell development which, remarkably, correspond exactly with the time points when either the pre-TCR or the TCR start to be expressed (35): If hyperactivable NFAT led to a signal-dependent decrease in the rate of cell cycle transit, cells expressing the hyperactivable protein could potentially increase in number relative to nonexpressing cells at the checkpoint just before the pre-TCR/TCR signal was received. Alternatively, the hyperactivable NFAT might confer a signal-specific proliferation or survival advantage at these developmental stages. Microarray and ChIP-chip analyses of enriched cell populations will be needed to distinguish these possibilities.

Our experiments also provide insights into the evolutionary conservation of the docking interactions of NFAT proteins with 2 of their regulatory enzymes, calcineurin and CK1. The SPRIEITPS > HPVIVITGP substitution of V-NFAT1 increases its affinity for calcineurin by 30- to 50-fold compared with the wild-type protein (from 25–30 μM for SPRIEITPS to 0.5–1 μM for HPVIVITGP) (41), indicating that a reasonably small change in binding affinity for calcineurin (<2.5 kcal/mole) results in hyperactivability and heightened activation (and therefore dysregulation) of NFAT1. The decrease in CK1 affinity caused by the FSILF > ASILA substitution has not been accurately measured, but it is likely to be modest, because mutation of a similar sequence in a peptide from β-catenin did not have a significant effect on its efficiency of phosphorylation by CK1 (42). Unexpectedly, even this degree of dysregulation of NFAT signaling led to a change in the “fitness” of cells and embryos that was detectable in a single generation. Expression of hyperactivable NFAT proteins later in development appears less deleterious to cellular fitness, however, suggesting that expressing hyperactivable NFAT at late developmental stages, or acutely in tissues of the adult (by breeding the R26 mice to Cre-ER mice, followed by tamoxifen administration, for instance), will be a valuable strategy for understanding the biological role of NFAT and identifying NFAT target genes in diverse tissues of interest.

Materials and Methods

Transfection of HEK293 Cells and Immunoblotting.

HEK293 cells were transfected with 10 μg of the retroviral constructs KMV-wild-type NFAT1, KMV-ASILA-NFAT1, KMV-VIVIT-NFAT1, and KMV-AV-NFAT1 by using calcium phosphate precipitation. Empty KMV-EGFP was used as a control. A total of 50 μg of protein lysate was resolved by SDS/PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting using the monoclonal mouse anti-HA antibody 12CA5 (1:1,000).

Mice.

CD4-Cre mice were purchsed from Taconic. All mice were on the C57BL/6 genetic background and were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions. All experiments were performed in concordance with protocols approved by the Harvard University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and by the Immune Disease Institute.

T Cell Isolation, Retroviral Transduction, and Differentiation.

T cell isolation, retroviral transduction, and differentiation were performed as described previously (43). A more detailed description is included in the SI Text.

T Cell Stimulation and Measurement of Cytokines.

On day 4 or 5 after isolation, T cells were stimulated with 10 nM PMA and various concentrations of ionomycin (0 nm to 1 μM) for 4 h. Brefeldin A (10 μg/mL; Sigma) was added for the last 2.5 h of stimulation. T cells were subsequently fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde, stained intracellularly for TNF (phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-mouse TNF; eBioscience) and IFN-γ (allophycoerythrin-conjugated anti-mouse IFN-γ; eBioscience), and analyzed by flow cytometry. TNF and IFN-γ concentrations in the cell supernatant were determined by using the BD Cytometric Bead Array (Mouse Th1/Th2 Cytokine Kit; BD Bioscences) according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer.

Conditional Gene Targeting and Genotyping.

The cDNAs encoding for HA-tagged V-NFAT1 and AV-NFAT1 were cloned into a modified version of pROSA26–1 (25), which also contains an frt-flanked IRES-EGFP cassette and a bovine polyadenylation sequence (26) (Fig. S1). B6 ES cells (Artemis Pharmaceuticals) derived from the C57BL/6 mouse strain were transfected, cultured, and selected as described previously (44). Chimeric mice with targeted R26 alleles were generated by blastocyst injection of heterozygous R26STOPflox-V-NFAT1 or R26STOPflox-AV-NFAT1 embryonic stem cell clones. Two targeted clones were injected for each allele. Germ-line transmission of the targeted alleles was achieved by breeding chimeric mice with C57BL/6 albino mice. Genotyping for the unrecombined R26 allele was performed by PCR using the primer pair 5′-CTG CGT GTT CGA ATT CGC CAA TGA-3′ and 5′-GGC AGC TTC TTT AGC AAC AAC CGT-3′. The recombined R26 allele (with the Neo-STOP cassette excised upon Cre recombination) was detected by PCR using the primers 5′-TTG AGG ACA AAC TCT TCG CGG TCT-3′ and 5′-CCC GCA TAG TCA GGA ACA TCG TAT-3′ or by detecting EGFP expression in lympocytes by flow cytometry.

Flow Cytometric Analysis.

For analysis of blood samples, a volume of ≈50 μL of peripheral blood was obtained from mouse tail veins by using heparinized glass capillaries (Drummond). Blood cells were washed twice in FACS buffer, stained with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies, and subsequently analyzed by flow cytometry. A detailed description of the analysis of specific subpopulations is included in the SI Text.

Immunohistochemistry.

Tissues were fixed by immersion in 4% formaldehyde and then dehydrated and embedded in paraffin for sections at 5–6 μm thickness. Sections were deparaffinated and pretreated with 1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0). Antibody incubations were performed with reagents from a DAB/horseradish peroxidase-based staining kit (Dako), including peroxidase-block pretreatment. Primary incubation was with a rabbit polyclonal antiserum to EGFP/YFP (ab290; Abcam). Following development of DAB staining, the sections were counterstained with hematoxylin.

NFAT1 Nuclear Translocation Assay.

NFAT1 translocation was assessed as described previously (45). A detailed description is included in the SI Text.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank D. Ghitza for help with blastocyst injections of ES cells and K. Ketman for help with cell sorting. This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants (to K.R. and A.R.); a T32 training grant (to S.G.), a Deutsche Krebshilfe postdoctoral fellowship (to M.R.M.), a Cancer Research Institute postdoctoral fellowship (to M.R.M.), a Canadian Institutes of Health Research postdoctoral fellowship (to S.S.), and a Leukemia and Lymphoma Society postdoctoral fellowship (to S.S.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0813296106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Crabtree GR, Olson EN. NFAT signaling: Choreographing the social lives of cells. Cell. 2002;109(Suppl):S67–S79. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00699-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hogan PG, Chen L, Nardone J, Rao A. Transcriptional regulation by calcium, calcineurin, and NFAT. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2205–2232. doi: 10.1101/gad.1102703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Macian F. NFAT proteins: Key regulators of T-cell development and function. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:472–484. doi: 10.1038/nri1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de la Pompa JL, et al. Role of the NF-ATc transcription factor in morphogenesis of cardiac valves and septum. Nature. 1998;392:182–186. doi: 10.1038/32419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ranger AM, et al. The transcription factor NF-ATc is essential for cardiac valve formation. Nature. 1998;392:186–190. doi: 10.1038/32426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang CP, et al. A field of myocardial-endocardial NFAT signaling underlies heart valve morphogenesis. Cell. 2004;118:649–663. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Molkentin JD, et al. A calcineurin-dependent transcriptional pathway for cardiac hypertrophy. Cell. 1998;93:215–228. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81573-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chin ER, et al. A calcineurin-dependent transcriptional pathway controls skeletal muscle fiber type. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2499–2509. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.16.2499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winslow MM, et al. Calcineurin/NFAT signaling in osteoblasts regulates bone mass. Dev Cell. 2006;10:771–782. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takayanagi H, et al. Induction and activation of the transcription factor NFATc1 (NFAT2) integrate RANKL signaling in terminal differentiation of osteoclasts. Dev Cell. 2002;3:889–901. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00369-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Graef IA, et al. Neurotrophins and netrins require calcineurin/NFAT signaling to stimulate outgrowth of embryonic axons. Cell. 2003;113:657–670. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00390-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horsley V, Aliprantis AO, Polak L, Glimcher LH, Fuchs E. NFATc1 balances quiescence and proliferation of skin stem cells. Cell. 2008;132:299–310. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graef IA, Gastier JM, Francke U, Crabtree GR. Evolutionary relationships among Rel domains indicate functional diversification by recombination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:5740–5745. doi: 10.1073/pnas.101602398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beals CR, Clipstone NA, Ho SN, Crabtree GR. Nuclear localization of NF-ATc by a calcineurin-dependent, cyclosporin-sensitive intramolecular interaction. Genes Dev. 1997;11:824–834. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.7.824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okamura H, et al. Concerted dephosphorylation of the transcription factor NFAT1 induces a conformational switch that regulates transcriptional activity. Mol Cell. 2000;6:539–550. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beals CR, Sheridan CM, Turck CW, Gardner P, Crabtree GR. Nuclear export of NF-ATc enhanced by glycogen synthase kinase-3. Science. 1997;275:1930–1934. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5308.1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu J, et al. Intramolecular masking of nuclear import signal on NF-AT4 by casein kinase I and MEKK1. Cell. 1998;93:851–861. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81445-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arron JR, et al. NFAT dysregulation by increased dosage of DSCR1 and DYRK1A on chromosome 21. Nature. 2006;441:595–600. doi: 10.1038/nature04678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gwack Y, et al. A genome-wide Drosophila RNAi screen identifies DYRK-family kinases as regulators of NFAT. Nature. 2006;441:646–650. doi: 10.1038/nature04631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okamura H, et al. A conserved docking motif for CK1 binding controls the nuclear localization of NFAT1. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:4184–4195. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.10.4184-4195.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aramburu J, et al. Selective inhibition of NFAT activation by a peptide spanning the calcineurin targeting site of NFAT. Mol Cell. 1998;1:627–637. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aramburu J, et al. Affinity-driven peptide selection of an NFAT inhibitor more selective than cyclosporin A. Science. 1999;285:2129–2133. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5436.2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Macian F, et al. Transcriptional mechanisms underlying lymphocyte tolerance. Cell. 2002;109:719–731. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00767-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xanthoudakis S, et al. An enhanced immune response in mice lacking the transcription factor NFAT1. Science. 1996;272:892–895. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5263.892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zambrowicz BP, et al. Disruption of overlapping transcripts in the ROSA beta geo 26 gene trap strain leads to widespread expression of beta-galactosidase in mouse embryos and hematopoietic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3789–3794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sasaki Y, et al. Canonical NF-kappaB activity, dispensable for B cell development, replaces BAFF-receptor signals and promotes B cell proliferation upon activation. Immunity. 2006;24:729–739. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Srinivas S, et al. Cre reporter strains produced by targeted insertion of EYFP and ECFP into the ROSA26 locus. BMC Dev Biol. 2001;1:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwenk F, Baron U, Rajewsky K. A cre-transgenic mouse strain for the ubiquitous deletion of loxP-flanked gene segments including deletion in germ cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:5080–5081. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.24.5080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huynh KD, Lee JT. Inheritance of a pre-inactivated paternal X chromosome in early mouse embryos. Nature. 2003;426:857–862. doi: 10.1038/nature02222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huynh KD, Lee JT. X-chromosome inactivation: A hypothesis linking ontogeny and phylogeny. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:410–418. doi: 10.1038/nrg1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheng MK, Disteche CM. Silence of the fathers: Early X inactivation. Bioessays. 2004;26:821–824. doi: 10.1002/bies.20082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Okamoto I, Otte AP, Allis CD, Reinberg D, Heard E. Epigenetic dynamics of imprinted X inactivation during early mouse development. Science. 2004;303:644–649. doi: 10.1126/science.1092727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mak W, et al. Reactivation of the paternal X chromosome in early mouse embryos. Science. 2004;303:666–669. doi: 10.1126/science.1092674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmidt-Supprian M, Rajewsky K. Vagaries of conditional gene targetting. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:665–668. doi: 10.1038/ni0707-665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Borowski C, et al. On the brink of becoming a T cell. Curr Opin Immunol. 2002;14:200–206. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(02)00322-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee PP, et al. A critical role for Dnmt1 and DNA methylation in T cell development, function, and survival. Immunity. 2001;15:763–774. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00227-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roy J, Li H, Hogan PG, Cyert MS. A conserved docking site modulates substrate affinity for calcineurin, signaling output, and in vivo function. Mol Cell. 2007;25:889–901. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kiani A, et al. Expression and regulation of NFAT (nuclear factors of activated T cells) in human CD34+ cells: Down-regulation upon myeloid differentiation. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;76:1057–1065. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0404259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kiani A, et al. Expression analysis of nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) during myeloid differentiation of CD34+ cells: Regulation of Fas ligand gene expression in megakaryocytes. Exp Hematol. 2007;35:757–770. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baksh S, et al. NFATc2-mediated repression of cyclin-dependent kinase 4 expression. Mol Cell. 2002;10:1071–1081. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00701-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li H, Zhang L, Rao A, Harrison SC, Hogan PG. Structure of calcineurin in complex with PVIVIT peptide: Portrait of a low-affinity signalling interaction. J Mol Biol. 2007;369:1296–1306. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bustos VH, et al. The first armadillo repeat is involved in the recognition and regulation of beta-catenin phosphorylation by protein kinase CK1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:19725–19730. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609424104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ansel KM, et al. Deletion of a conserved Il4 silencer impairs T helper type 1-mediated immunity. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1251–1259. doi: 10.1038/ni1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schmidt-Supprian M, et al. NEMO/IKK gamma-deficient mice model incontinentia pigmenti. Mol Cell. 2000;5:981–992. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80263-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oh-Hora M, et al. Dual functions for the endoplasmic reticulum calcium sensors STIM1 and STIM2 in T cell activation and tolerance. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:432–443. doi: 10.1038/ni1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.