Abstract

Objective

Environmental chemicals are readily measured in human milk. Although it is imperative to conduct studies on frequency of detection and effects of exposures to environmental chemicals in human milk, the potential impact of reporting individual test results to lactating women is poorly understood. The purpose of this study was to determine if mothers want to know if chemicals are in their breastmilk and if knowing the results would alter their breastfeeding practices.

Methods

We surveyed 381 mothers who were participating in a longitudinal birth cohort about whether they wanted to receive individual test results for environmental chemicals in their milk and whether they would alter their breastfeeding patterns if they were told that their milk contained “low” or “high” levels of phthalates.

Results

Among the women who breastfed, 68% said that they wanted to know if there were chemicals in their breastmilk. Of breastfeeding women, 78% and 93% of mothers reported that they would either discontinue breastfeeding sooner than intended or pump and discard their milk if they were told they had “low” or “high” levels of phthalates in their milk, respectively. African American women were significantly more likely than Caucasian women to report that they would immediately wean if told of phthalates in their milk.

Conclusions

Concern about environmental chemicals in breastmilk may lead to early termination of breastfeeding. Chemical manufacturers and researchers should recognize the potential implications of isolating and reporting environmental chemicals in breastmilk.

Background

Over 70,000 manufactured chemicals are approved for use in the United States, with approximately 1,500 more chemicals added to this list annually.1 Unregulated use of chemicals and their metabolites can result in widespread human exposure via ingestion, inhalation, and dermal contact, as well as bioaccumulation in food sources. Nonionized, highly persistent chemicals of low molecular weight easily traverse biological membranes, and the high fat content of human milk is an efficient vehicle for lipophilic agents.2–4 For many persistent chemicals, breastmilk removal can be a major route of elimination of these substances.2 Breastfed infants are at the top of the human food chain and potentially are at highest risk for detrimental consequences from exposure to harmful, accumulated chemicals.5

Detectable levels of chemicals in the breastmilk of women in the United States have been reported since the 1950s.6 Since then, numerous chemicals have been detected in human milk throughout the world.7, 8 Although efforts to standardize research methodology and understand the human health effects of newborns exposed to environmental chemicals in human milk have been proposed,9 the health effects of exposure to the vast majority of these chemicals are largely unknown.10, 11 There are increasing efforts to study the impacts of human exposures to environmental contaminants in breastmilk and conduct surveillance to quantify human exposure to environmental contaminants, but it remains unclear whether to report individual test results to study participants. Some investigators and ethicists believe that study participants have the right to receive individual test results.12–14 Others have argued results that are not clinically meaningful can lead to undue alarm and unanticipated consequences, such as labeling effect15 and abrupt cessation of breastfeeding.16

There is a paucity of research on the impact of reporting individual test results of environmental chemicals in breastmilk to individual lactating women. The only published description of mothers' reactions to being told that they have environmental chemicals in their breastmilk is derived from a cohort of 97 women exposed to polybrominated biphenyl (PBB) in the 1970s via contaminated cow feed.17 Ninety-six percent of breastmilk samples from a representative population of lactating women in the geographical area of exposure showed detectable levels of PBB.18 Despite considerable public health education efforts at the time, only 28% of the subjects reported that they had a “good” understanding of how to interpret what they were told to make an informed decision on whether to continue breastfeeding upon receiving the result of their PBB level.17 Thirty-one percent of the mothers surveyed said that their result ultimately did have some bearing on their decision to continue breastfeeding; 77% reported that they would advise other women to get their milk tested. While this study was conducted with subjects with a well-recognized exposure to contaminated foods, it is unknown what women would do if they were informed of lower-level exposures to environmental chemicals. The purpose of our study was to determine if breastfeeding women want to be informed of the levels of environmental chemicals in their milk and whether they would alter their breastfeeding patterns if they were told that their milk contained “low” or “high” levels of phthalates.

Design and Methods

We conducted a survey of breastfeeding mothers who were participating in a Cincinnati Children's Environmental Health Center research project entitled the “Study of Prevalent Neurotoxicants in Children.” The purpose of this prospective, longitudinal cohort study is to examine environmental exposures of pregnant women and their children and investigate developmental outcomes throughout early childhood.

We obtained a representative sample of pregnant women in our area by obtaining lists of new obstetrical patients from eight participating offices in the Cincinnati Metropolitan Area. Letters were mailed to women in the sampling frame describing the study and offering them an opportunity to find out more information. Potential participants were able to decline contact by returning a postcard or calling the staff by telephone. Subsequently, study coordinators contacted the women who did not actively decline participation to determine their eligibility. Eligibility was based on: maternal age greater than 18 years; estimated infant gestational age of 16–19 weeks; having a home address within the designated five Ohio counties surrounding the medical center where the study was to be conducted; intention to continue prenatal and postpartum care with participating obstetrical practices or hospitals; no plans to move from the five-county area; able to understand the English language; and no existing medical condition that would interfere with participation (i.e., human immunodeficiency virus infection, cancer, diabetes, or mental health disorder requiring antipsychotic medication).

Of 8,878 women in the original sampling frame, we screened 5,512 women from March 2003 through February 2006. Of these women, 1,263 (23%) were eligible to participate in the study. Of the eligible women, 468 (37%) agreed to participate. Following verbal consent, the prospective participant was mailed the consent form. During the next prenatal visit, a trained study coordinator reviewed the consent form, verified that each woman understood the main points of the study using a check list, and obtained consent. The cohort assembly, data collection, and analyses were approved by the institutional review boards at the Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, the three local maternity hospitals where mothers delivered, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A Waiver of Authorization under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act through the Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center Institutional Review Board was obtained prior to performing the initial screening.19

We included questions about the mother's concerns regarding chemicals in their breastmilk at the 12-month post-partum survey. Because it was not feasible to ask mothers about their concerns about multiple environmental chemicals, we asked them whether they would alter their patterns of breastfeeding if they were informed that their breastmilk contained “low” or “high” levels of phthalates. Phthalates are chemicals found in many household items, including plastics, toys, cosmetics, and fragrances. Although mothers may or may not have heard about phthalates previously, they were likely to come in contact with these items on a daily basis. The following three questions and response choices were asked to the breastfeeding mothers:

-

The American Academy of Pediatrics states that breastmilk is the ideal nutrition for infants even though some mothers' milk has been shown to contain environmental chemicals. At this time, doctors do not know what potential problems, if any, may arise if a mother has environmental chemicals in her breastmilk. With which of the following statements do you most agree?

I think that mothers should be told what environmental toxins are in their breastmilk EVEN THOUGH DOCTORS ARE NOT ABLE to advise mothers about what to do with this information.

I think that mothers should be told what environmental toxins are in their breastmilk ONLY AFTER DOCTORS ARE ABLE to advise mothers about what to do with this information.

Don't know

Refusee. Not applicable

-

While you were feeding breastmilk to (infant's name inserted here), which of the following best describes what you would have done if you were told that your breastmilk had LOW levels of phthalates, a group of chemicals that is used to make plastic more flexible?

Immediately quit feeding my child breastmilk

Feed my child breastmilk for a little longer, but wean earlier than if I did not know that my breastmilk had contaminants

Not change my behavior based on the information

Pump my milk but throw it away and feed my child formula

Not applicable

Refuse

Don't know

-

While you were feeding breastmilk to (infant's name inserted here), which of the following best describes what you would have done if you were told that your breastmilk had HIGH levels of phthalates, a group of chemicals that is used to make plastic more flexible?

Immediately quit feeding my child breastmilk

Feed my child breastmilk for a little longer, but wean earlier than if I did not know that my breastmilk had contaminants

Not change my behavior based on the information

Pump my milk but throw it away and feed my child formula

Not applicable

Refuse

Don't know

Data were analyzed using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). We compared descriptive characteristics of the mothers who ever breastfed and those who did not using χ2 analysis for categorical variables and Student's t test for continuous variables. We calculated the frequencies of breastfeeding among the different racial and sociodemographic backgrounds. We compared the descriptive characteristics of the breastfeeding mothers who wanted to know the results of chemicals in their milk with those who did not using χ2 and Student's t tests. Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to compare the responses of the group that wanted to know of the results to the group that did not. The following independent variables were included in the initial model: race, education, marital status, annual household income, tobacco smoke exposure, and insecticide use. A backward elimination approach was used, and then variables were re-entered into the model to examine the effect on the remaining independent variable(s). Lastly, we compared the behavioral choices of Caucasian and African American mothers when told that they had “low” or “high” levels of phthalates in their milk using χ2. Since the group of non-Caucasian, non-African American mothers was a small, relatively heterogeneous subset, we removed them from this final analysis.

Results

Of the 468 women who initially agreed to participate, 67 (14%) dropped out before their infants were born. The primary reason for leaving the study was the time commitment required. Three hundred ninety-eight of the remaining 401 women delivered live-born infants, nine of which were sets of twins. Six mothers dropped out immediately after delivery, and 11 never answered the infant feeding questions. We utilized responses of the remaining 381 of the potentially eligible 398 women in the cohort (96%).

The demographic responses of the participants are shown in Table 1. Of this group, 81% (310 of 381) fed the index child at least some breastmilk. Breastfeeding was initiated by 87% (211 of 242) of Caucasian, non-Hispanic mothers, 67% (76 of 114) of African American, non-Hispanic mothers, and 92% (23 of 25) of mothers in the “other categories,” including Hispanic, Asian/Pacific, and American Indian women. The value for overall median weeks of breastfeeding and interquartile range was 23 (7, 48) weeks. Consistent with national breastfeeding trends, mothers in this study were more likely to breastfeed if they were not African American, older, married, and nonsmokers and had a higher annual household income. Use of insecticides in the home, a potential marker of awareness of environmental chemical exposure, was not significantly different between those who did and did not breastfeed.

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of Participants Based on Having Ever Breastfed

| Ever breastfed (n = 310) | Never breastfed (n = 71) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race | |||

| Caucasian, non-Hispanic | 211 (68%) | 31 (44%) | |

| African American, non-Hispanic | 76 (25%) | 38 (54%) | <0.0001 |

| Other | 23 (7%) | 2 (3%) | |

| Education | |||

| <High school | 18 (6%) | 20 (28%) | |

| High school graduate or GED | 32 (10%) | 17 (24%) | |

| Some college/technical | 80 (26%) | 17 (24%) | <0.0001 |

| College graduate | 100 (32%) | 13 (18%) | |

| Postgraduate | 80 (26%) | 4 (6%) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 228 (74%) | 25 (35%) | |

| Not married, live-in partner | 35 (11%) | 15 (21%) | <0.0001 |

| Not married, live alone | 47 (15%) | 31 (44%) | |

| Annual household income | |||

| ≤$25,000 | 60 (19%) | 36 (51%) | <0.0001 |

| $25,000–50,000 | 67 (22%) | 14 (20%) | |

| $50,000–80,000 | 81 (26%) | 11 (15%) | |

| >$80,000 | 95 (31%) | 9 (13%) | |

| Age at last menstruation (years) | 29 ± 5.6 | 27 ± 6.4 | 0.002 |

| Ever smoked | |||

| Yes | 90 (29%) | 71 (45%) | 0.01 |

| No | 220 (71%) | 39 (55%) | |

| Reported insecticide use | |||

| Yes | 237 (76%) | 58 (82%) | |

| No | 73 (24%) | 13 (18%) | 0.34 |

| Never | 178 (57%) | 48 (68%) | |

Race, education, marital status, income, smoking status, and insecticide use are presented as n (%). Age at last menstruation is reported as mean ± SD.

Of the 310 breastfeeding mothers, 288 (93%) completed the 12-month infant feeding questionnaire that contained the environmental health questions. At the time of the survey, there had not been testing of any breastmilk samples. Although we informed the participants that doctors may not be able help interpret the results, 68% (196 of 288) of women responded that they wanted to know if there were chemicals in their breastmilk (Table 2). The only significant characteristic that distinguished women who wanted to know if there were chemicals in their breastmilk versus those who did not was race: A greater percentage of non-Caucasian mothers wanted to know if there were contaminants in their milk compared with Caucasian mothers. Using logistic regression that included variables in the model related to breastfeeding (race, education, marital status, household income, maternal age, tobacco smoke exposure, insecticide use, and duration of breastfeeding), race was the only variable significantly associated with wanting to know results of breastmilk chemical levels (p = 0.005).

Table 2.

Descriptive Characteristics of Participants Based on Wanting to Know of Chemicals in Their Breastmilk

| Want to know of chemicals (n = 196) | Don't want to know of chemicals (n = 92) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race | |||

| Caucasian, non-Hispanic | 126 (64%) | 78 (85%) | |

| African American, non-Hispanic | 52 (26%) | 12 (13%) | 0.001 |

| Other | 18 (9%) | 2 (2%) | |

| Education | |||

| <High school | 18 (6%) | 20 (28%) | |

| High school graduate or GED | 32 (10%) | 17 (24%) | 0.43 |

| Some college/technical | 80 (26%) | 17 (24%) | |

| College graduate | 100 (32%) | 13 (18%) | |

| Postgraduate | 80 (26%) | 4 (6%) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 142 (72%) | 77 (84%) | |

| Not married, live-in partner | 28 (12%) | 8 (9%) | 0.10 |

| Not married, live alone | 30 (15%) | 7 (8%) | |

| Annual household income | |||

| ≤$25,000 | 40 (20%) | 9 (10%) | |

| $25,000–50,000 | 41 (21%) | 24 (26%) | 0.11 |

| $50,000–80,000 | 48 (24%) | 29 (32%) | |

| >$80,000 | 63 (32%) | 29 (32%) | |

| Age at last menstruation (years) | 29 ± 5.8 | 30 ± 5.0 | 0.17 |

| Ever smoked | |||

| Yes | 61 (31%) | 19 (21%) | 0.25 |

| No | 135 (69%) | 73 (79%) | |

| Reported insecticide use | |||

| Yes | 146 (74%) | 73 (79%) | |

| No | 50 (26%) | 19 (21%) | 0.37 |

| Never | 120 (61%) | 45 (49%) | |

| Duration of breastfeeding | 23 (7, 49) | 31 (12, 51) | 0.53 |

Race, education, marital status, income, smoking status, and insecticide use are presented as n (%). Age at last menstruation is reported as mean ± SD. Duration of breastfeeding is reported as median weeks with interquartile range.

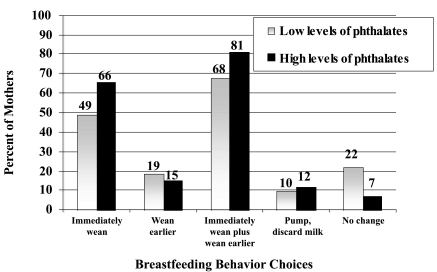

For the 196 mothers who wanted to know if they had chemicals in their milk, 49% and 66% said that they would immediately wean if they were told that their breastmilk contained “low” or “high” amounts of phthalates, respectively (Fig. 1). When the number of mothers who said that they would wean earlier than expected compared with those who would wean immediately was included, 68% and 81%, respectively, said that they would stop breastfeeding. Only 22% of mothers in the study said that at “low” levels of phthalates they would not change their breastfeeding practices, and 7% of mothers said that they would not change their practices when told of “high” levels of phthalates.

FIG. 1.

Breastfeeding behavior choices of all breastfeeding mothers in the study when told they have low and high levels of phthalates in their breastmilk (n = 196).

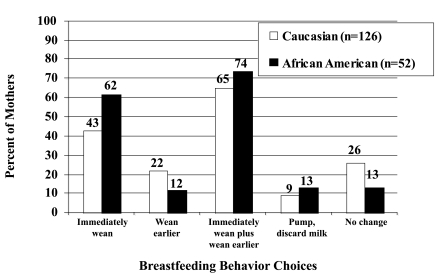

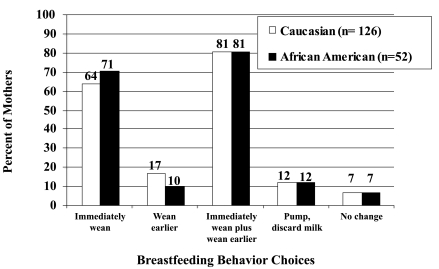

African American women were more likely to report that they would wean if they were informed their breastmilk contained “low-level” phthalates compared with Caucasian women (62% vs. 43%) (Fig. 2). Over two-thirds of both groups would wean earlier than intended for “low” levels. For “high” levels, 81% of both groups said that they would wean earlier than intended (Fig. 3). Although we provided no descriptions regarding any specific characteristics of phthalates, their safety profile, or potential outcomes, fewer than 10% of both Caucasian and African American indicated that they would not change their breastfeeding practice when told of “high levels” of chemicals in their milk.

FIG. 2.

Breastfeeding behavior of Caucasian versus African American mothers when told they have low levels of phthalates in their breastmilk (n = 178).

FIG. 3.

Breastfeeding behavior of Caucasian versus African American mothers when told they have high levels of phthalates in their breastmilk (n = 178).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to determine if breastfeeding women want to be informed about environmental chemicals in their milk and what they would do if they knew these results. Although previously reported descriptive studies cite a wide variety of chemicals found in breastmilk, to our knowledge, participants are rarely asked whether they would alter their breastfeeding patterns if they knew their individual test results. Phthalates, which were used as a hypothetical chemical for this study, are ubiquitous in the environment.20 Although the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that breastfeeding should not be discontinued when there is “everyday” exposure to environmental chemicals,21 over two-thirds of mothers in our study said that they would stop breastfeeding before they originally intended due to the contamination of their breastmilk. Mothers indicated that they would stop breastfeeding despite being given no clear guidelines of potential detrimental outcomes to their infants associated with this chemical group.

African American mothers in this study were more likely to request the individual test results for chemicals in their breastmilk than Caucasian mothers. African American mothers also reported that they would be more likely to wean than Caucasian mothers at lower phthalate exposures. Although we did not specifically ask each woman her reasons for wanting to know her individual test results, African American women have been shown to have higher serum and urine levels of a variety of environmental contaminants than Caucasians, have a disproportionate exposure to environmental hazards based on their location of residence and occupations, and often have fewer resources to change their circumstances.22–25 These results are especially worrisome because African American women in the United States already have lower breastfeeding rates than Caucasian women.26 Reporting of individual test results for environmental contaminants in breastmilk to African American women may therefore result in a disproportionate number of African American children being unnecessarily weaned from the breast. Still, it is unclear whether it is appropriate to withhold such information from study participants, especially vulnerable populations.

The primary limitation of this study is that the results may not be generalizable to other groups. The women who agreed to participate in the parent study did so knowing that it was specifically designed to examine health impacts of environmental contaminants on children. For example, the mothers participated in extensive interviews that may have led them to learn more about the chemicals being studied, they had prenatal care, and they were told upon enrollment that they would receive free breast pump equipment (about a $45 retail value) at the 1-month visit if they were still breastfeeding. Participants in this study had a higher breastfeeding initiation rate (81%) than has been observed for the geographic area where they were selected (65.0 ± 6.6).27

This study also was limited by the fact that we only asked mothers about “high” and “low” levels of phthalates. We cannot determine if a mother would wean if given an exact quantification of the phthalates in her milk. Indeed, detection of phthalates in breastmilk may be particularly challenging; a recent study of 42 women showed that phthalates were below the level of detection in the majority of human milk samples, despite reporting measurable quantities in urine.28 We also do not know if participants would wean if they were told that they had more than one chemical in their milk or if they would choose not to breastfeed during subsequent lactation cycles if they were ever told their milk contained chemicals. Future studies on women's choices about breastfeeding and environmental chemical exposure need to include non-breastfeeding mothers to discern if potential exposure to environmental contaminants is one reason that women choose not to breastfeed in the first place.

What our study did show, however, was that informing mothers about contamination of breastmilk with environmental chemicals has the potential to reduce the duration of breastfeeding. It is imperative that chemical manufacturers and researchers recognize the potential consequences of environmental contamination in breastmilk. As it is currently done for medications in breastmilk, chemical manufacturers should actively participate in better definition of a breastfed infant's potential exposure to environmental chemicals. These activities should include further descriptive studies of chemicals found in breastmilk, determination of a “relative infant dose” based on amount of maternal exposure, surveys to identify whether the public is willing to accept uncertainties of exposures, and dissemination of this information to the public. Researchers conducting human studies of exposures to environmental chemicals need to balance research subjects' right to receive individual test results with potential unintended consequences, such as premature weaning. Women and their healthcare providers need to be able to make informed decisions about whether the benefits of breastfeeding outweigh the risk of infant exposure.

Conclusions

The goal of this study was to better understand whether women would alter their breastfeeding patterns if they were informed about environmental chemicals in their milk. Two-thirds of the women in this study said that they would want to know if their breastmilk contained chemicals, and over three-fourths reported that they would wean earlier than intended if they had phthalates in their breastmilk. African American women reported that they would wean more often than Caucasian women. Chemical manufacturers should provide a risk assessment of exposure for the breastfed infant. Researchers need to balance subjects' right to receive results with potential unintended consequences. If women's knowledge about the presence of environmental chemicals in breastmilk can lead to early termination of breastfeeding, it is imperative that we find ways to reduce these exposures or determine that they are innocuous.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants P01ES011261 and K23ES014691 from the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Chemical testing and information home page. http://www.epa.gov/opptintr/chemtest/index.htm. [May 1;2008 ]. http://www.epa.gov/opptintr/chemtest/index.htm

- 2.Gallenberg LA. Vodicnik MJ. Transfer of persistent chemicals in milk. Drug Metab Rev. 1989;21:277–317. doi: 10.3109/03602538909029943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berlin CM., Jr Kacew S. Lawrence R, et al. Criteria for chemical selection for programs on human milk surveillance and research for environmental chemicals. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2002;65:1839–1851. doi: 10.1080/00984100290071748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Transfer of drugs and other chemicals into human milk. Pediatrics. 2001;108:776–789. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.3.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rogan WJ. Pollutants in breast milk. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1996;150:981–990. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170340095018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laug EP. Kunze FM. Prickett CS. Occurrence of DDT in human fat and milk. Arch Ind Hyg Occup Med. 1951;3:245–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.LaKind JS. Berlin CM. Naiman DQ. Infant exposure to chemicals in breast milk in the United States: What we need to learn from a breast milk monitoring program. Environ Health Perspect. 2001;109:75–88. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0110975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sim MR. McNeil JJ. Monitoring chemical exposure using breast milk: A methodological review. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;136:1–11. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.LaKind JS. Preface: Workshop on human milk surveillance and research on environmental chemicals in the United States. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2005;68:1681. doi: 10.1080/15287390500225534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Claudio L. NIEHS investigates links between children, the environment, and neurotoxicity. Environ Health Perspect. 2001;109:A258–A261. doi: 10.1289/ehp.109-a258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lanphear BP. Vorhees CV. Bellinger DC. Protecting children from environmental toxins. PLoS Med. 2005;2(3):e61. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bunin GR. Kazak AE. Mitelman O. Informing subjects of epidemiologic study results. Children's Cancer Group. Pediatrics. 1996;97:486–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernandez CV. Kodish E. Weijer C. Informing study participants of research results: An ethical imperative. IRB. 2003;25(3):12–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Partridge AH. Winer EP. Informing clinical trial participants about study results. JAMA. 2002;288:363–365. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Research Involving Human Biological Materials: Ethical Issues Policy Guidance. National Bioethics Advisory Commission; Rockville, MD: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berlin CM., Jr LaKind JS. Sonawane BR, et al. Conclusions, research needs, and recommendations of the expert panel: Technical workshop on human milk surveillance and research for environmental chemicals in the United States. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2002;65:1929–1935. doi: 10.1080/00984100290071801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hatcher SL. The psychological experience of nursing mothers upon learning of a toxic substance in their breast milk. Psychiatry. 1982;45:172–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brilliant LB. Wilcox K. Van Amburg G, et al. Breast-milk monitoring to measure Michigan's contamination with poly-brominated biphenyls. Lancet. 1978;2:643–646. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)92758-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Office of Human Research Protection. Code of Federal Regulations. Title 45, Part 46. Protection of human subjects. http://oshr.od.nih.gov/guidelines/45cfr46.html. [May 1;2008 ]. http://oshr.od.nih.gov/guidelines/45cfr46.html

- 20.Staples CA. Peterson DR. Parkerton TF, et al. The environmental fate of phthalate esters: A literature review. Chemosphere. 1997;35:667–749. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gartner LM. Morton J. Lawrence RA, et al. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2005;115:496–506. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Disease Control Prevention. Second National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals. National Center for Environmental Health; Atlanta: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frumkin H. Walker ED. Friedman-Jimenez G. Minority workers and communities. Occup Med. 1999;14:495–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maantay J. Zoning, equity, and public health. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1033–1041. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.7.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Powell DL. Stewart V. Children. The unwitting target of environmental injustices. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2001;48:1291–1305. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70375-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li R. Darling N. Maurice E, et al. Breastfeeding rates in the United States by characteristics of the child, mother, or family: The 2002 National Immunization Survey. Pediatrics. 2005;115:e31–e37. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Breastfeeding Practices—Results from the National Immunization Survey. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta: 2005. [Jul 1;2008 ]. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hogberg J. Hanberg A. Berglund M, et al. Phthalate diesters and their metabolites in human breast milk, blood or serum, and urine as biomarkers of exposure in vulnerable populations. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:334–339. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]