Abstract

Background and Purpose

Familial aggregation of intracranial aneurysms (IA) strongly suggests a genetic contribution to pathogenesis. However, genetic risk factors have yet to be defined. For families affected by aortic aneurysms, specific gene variants have been identified, many affecting the receptors to transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β). In recent work, we found that aortic and intracranial aneurysms may share a common genetic basis in some families. We hypothesized, therefore, that mutations in TGF-β receptors might also play a role in IA pathogenesis.

Methods

To identify genetic variants in TGF-β and its receptors, TGFB1, TGFBR1, TGFBR2, ACVR1, TGFBR3 and ENG were directly sequenced in 44 unrelated patients with familial IA. Novel variants were confirmed by restriction digestion analyses, and allele frequencies were analyzed in cases versus individuals without known intracranial disease. Similarly, allele frequencies of a subset of known SNPs in each gene were also analyzed for association with IA.

Results

No mutations were found in TGFB1, TGFBR1, TGFBR2 or ACVR1. Novel variants identified in ENG (p.A60E) and TGFBR3 (p.W112R) were not detected in at least 892 reference chromosomes. ENG p.A60E showed significant association with familial IA in case-control studies (P = 0.0080). No association with IA could be found for any of the known polymorphisms tested.

Conclusions

Mutations in TGF-β receptor genes are not a major cause of IA. However, we identified rare variants in ENG and TGFBR3 that may be important for IA pathogenesis in a subset of families.

Keywords: aneurysm, endoglin, betaglycan, TGFBR1, TGFBR2

Introduction

Familial aggregation of saccular intracranial aneurysms (IA) indicates a genetic role in the pathogenesis of disease 1. Up to 20% of IA patients have a positive family history 2–5 and the risk of IA rupture is seven-fold higher among first-degree relatives compared to second-degree relatives 6. Affected pairs of monozygotic twins have been identified 7.

Although more than 500 families affected by IA have been described to date, no single gene variant has been conclusively shown to cause IA formation or rupture, neither in a single family nor a subpopulation of patients. The clinical features of IA have made genetic analyses difficult. Many affected relatives die due to the catastrophic nature of rupture of an IA, therefore making the collection of DNA samples difficult. Aneurysms typically arise late in life, even in the sixth and seventh decades, making the characterization of unaffected relatives uncertain. Most importantly, there is significant genetic heterogeneity associated with this condition, in which different genes or genetic mechanisms may demonstrate variable expression in terms of age of onset or disease penetrance. Several patterns of inheritance have been observed in families with IA and a single Mendelian model of inheritance has not been established 8.

Although many loci have been linked to familial IA risk, disease-causing genetic variants have not been identified in these intervals 1. Similarly, association studies involving candidate genes, such as elastin, collagen, and matrix metalloproteinases, have not shown definitive results 1.

In some families, the formation of IA may share a genetic predisposition with aortic aneurysms (AA). Kim et al. have reported that in a group of 274 IA patients, 10% had a family history of AA9. Furthermore, pedigree analyses suggested that an autosomal dominant inheritance with decreased penetrance and variable expression was likely in some families. Conversely, several families with AA have been described in which some family members were diagnosed with IA10, 11. Sharing common risk factors such as hypertension and smoking, IA and AA display similar pathologies including degeneration of the extracellular matrix, destruction of elastic lamina and loss of media. Both show increased activity of matrix metalloproteinases12, 13, apoptosis14, 15 and inflammatory cell infiltration16, 17.

Based on these data, we hypothesized that formation of IA and AA might share common genetic mechanisms. Gene mutations leading to thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections (TAAD) have been characterized. TAAD can be inherited in isolation (familial TAAD) or in association with genetic syndromes such as Marfan syndrome (MFS) and Loeys-Dietz syndrome (LDS). Heterozygous mutations in TGF-β receptor genes, TGFBR1 and TGFBR2, have been reported in familial TAAD, MFS and LDS18–21. The gene that is responsible for most cases of MFS, the FBN1 gene encoding fibrillin-1, is required for effective TGF-β activation. These suggest that dysregulation of TGF-β signaling might be involved in TAAD pathogenesis. Accordingly, the expression of genes normally stimulated by TGF-β, such as collagen and connective tissue growth factor, was upregulated in tissue of LDS patients. Furthermore, aneurysms that develop in an accepted mouse model of MFS (fbn1C139G/+) are associated with increased TGF-β signaling and can be prevented by TGF-β antagonists22.

TGF-β is a polypeptide that plays diverse roles in cell proliferation and differentiation, apoptosis, and extracellular matrix formation23, 24. TGF-β transduces its signals via types I and II receptors, encoded by TGFBR1 and TGFBR2. The ligand-bound type-II receptor phosphorylates the glycine/serine-rich domain of the type-I receptor, which activates signal transduction.

To test our hypothesis that dysregulation of TGF-β signaling may be common to both TAAD and IA, we sequenced the coding region of TGFBR1 and TGFBR2 in 44 unrelated IA patients. We also sequenced genes encoding the TGF-β1 ligand, another TGF-β receptor (ACVR1), and co-receptors endoglin (ENG) and betaglycan (TGFBR3). We report the absence of mutations in TGFBR1 and TGFBR2 and the identification of novel variants in ENG and TGFBR3.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

Between July 2000 and December 2002, 378 patients with saccular IA treated by the senior author (DHK) were eligible for enrollment. Excluded were 56 patients with dissecting or fusiform aneurysms, or patients with associated abnormalities such as an arteriovenous malformation. Enrollment was completed in 274 patients (85%). This cohort does not represent a population-based study and referral bias is a possibility because the patient population was referred to a single surgeon.

Among the study participants were 73.5% female and 26.5% male. The ethnic background was Caucasian in 61.5%, African-American in 18.9%, and Hispanic in 16.4%. The average age of the patients was 53.7 years. There was no difference in the age of presentation between men and women (52.1 and 54.3 years, respectively) or between ethnic groups.

When a patient had a first-degree relative with either an IA or AA, that family was identified as having a possible familial aneurysm (defined as two or more affected first degree relatives). In such families, all relatives were also approached to participate in the study.

If family members reported an aneurysm or a history suggestive for aneurysm such as “stroke” or “sudden death,” the diagnosis was confirmed with medical records, death certificates, or autopsy reports before a positive finding was noted. When the aneurysm history could not be confirmed, the family member was not noted as having an aneurysm. Patients with infundibular enlargements were not classified as having IAs.

Of the 274 patients enrolled, 79 patients (28.8%) had a family history of aneurysms (familial cases) and the remaining 195 (71.2%) did not have any family history of aneurysms (sporadic cases). Of the familial cases, 50 patients (18.2%) had a family history of IA only, while 29 (10.6%) had a family history of both IA and AA. Of the 50 patients with family history of IA only, 6 had polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), known to increase the risk of IA development.

Families with history of both AA and IA, and families affected by ADPKD (where the gene defects are known), were excluded from our studies. Hence, our study population consisted of 44 probands from families with history of IA only (70.5% Caucasian, 18.2% African-American, 6.8% Hispanic 4.5% and Asian; ages 28–92 years, average of 55 years; 75% female, 25% male). Ninety-two randomly-selected sporadic patients were also analyzed (100% Caucasian; age 24–84 years, average of 54 years; 67% female, 33% male).

For the evaluation of allele frequencies of novel variants in the general population, we used a group of 492 unrelated individuals (we termed “General Population I”) without known intracranial disease (42.7% Caucasian, 21.7% African-American, 3.9% Hispanic, 1.6% Asian, and 30.1% unknown). Of the 492 individuals, 192 specified their age (16–95, average of 50 years) and 396 specified their gender (52.5% female, 47.5% male). No diagnostic tests were performed on these individuals to exclude the presence of IA.

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston and the Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. All information gathered was coded and confidentiality maintained.

DNA Sequencing

Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood or buccal cells using DNA purification kits (PureGene and Oragene). DNA amplifications were done using intron-based, exon-specific primers (Table 1) using the following conditions: 95°C for 10 min; 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 sec, 60°C for 30 sec and 72°C for 1 min, and a final 72°C for 10 min. For most reactions, the forward M13 universal primer tag was appended to the 5’ end of the forward primer, and the reverse M13 primer tag to the 5’ end of the reverse primer, allowing all forward and reverse sequencing reactions to be performed using the forward and reverse M13 primers, respectively. Sequencing reactions were performed using Big Dye chemistry under the following conditions: 96°C, 10 sec; 50°C, 5 sec; 60°C, 4 min. The products were purified using CleanSEQ magnetic beads (Agencourt) and analyzed on the ABI3100 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). Mutation analyses were done by visual inspection of aligned sequences in comparison with published genomic DNA sequences using Sequence Manager 6.1 (DNA Star) and Mutation Surveyor. The NCBI SNP database (dbSNP; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/) was used as reference for identifying known polymorphisms.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Forward primers (5' -> 3') | Reverse primers (5' -> 3') | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| A. Oligonucleotides used for sequencing of coding regions | |||

| TGFB1 | Exon 1 | GAGGACCTCAGCTTTCCCTC | GCCAGTTTCTTCTGCCAGTC |

| Exon 2 | TCAGAGACTGACTCCACCCC | TTCAGGGACCATCTAGGTGG | |

| Exon 3 | TTTTTCTCCACCCCTCCTCT | ATCACTCAGGTTTCCATGCC | |

| Exon 4–5 | AGAGAGCTGCAGTGAGAGGG | AGCCCTCCAAGCTAAAGGAG | |

| Exon 6 | AGGGAGACCCAGATGGAGAT | CCCTCTCTAGCTTCCTGCCT | |

| Exon 7 | CGAATTGGAGATGGGAAGAG | ATCAGAGTCCCTGCATCTCA | |

| TGFBR1 | Exon 1 | CCTCCGAGCAGTTACAAAGG | GCGCCATGTTTGAGAAAGAG |

| Exon 2 | TGCTACATTTCCTTGGGCTT | AACACATACCCAGGAGGCAG | |

| Exon 3 | CTGACAGAGCTGGTGTGCAT | GGAGCTGACTTATTGATTCGC | |

| Exon 4 | CCCTCTAGCAGGAGTTTCTGG | AGGAATGCTATCAAGAGTCAAGA | |

| Exon 5 | TTGCAGTGTGTGACTCAGGA | GATGCGGTTTTGTCATGTTG | |

| Exon 6 | GTGGGCTGAAATGCTTTGAT | ATTTTCTGGAAGGGCAACCT | |

| Exon 7 | AGATCATGAGGCAGATAGTGTG | GCCTTTGTTTTCTCTGGCAC | |

| Exon 8 | GGAAGTGGCTTGTGGATACAG | AAAGGCCACTGCAAATGTTC | |

| Exon 9 | TCTTTGTCCACCTGCTTTCC | AGTGCACAGAAAGGACCCAC | |

| TGFBR2 | Exon 1 | GGACTCCTG TGCAGCTTCC | CACAATCCCTGCAGCTACG |

| Exon 1a | AACTTTGAAGAAAACATATTGACCA | AAGCAGTGAGGGAGCATGAC | |

| Exon 2 | TGAAATTGCATAACATCTTCAGG | GGAAAGGGAAATGGAACAGG | |

| Exon 3 | CAGATTGCCTTTCTGTCTGGA | CCACAGGAGGAATGTGCTCT | |

| Exon 4a | GCACTTGCATCCCTGAAATAA | ACCTCAGCAAAGCGACCTT | |

| Exon 4b | GGAAGATGACCGCTCTGACA | ACTGTGGAGGTGAGCAATCC | |

| Exon 4c | GGGGAAACAATACTGGCTGA | TTCCCTAGACCAGTG TCCAGA | |

| Exon 5 | AGGGGCCACCATCAGCTA | CCCTGGAATAATGCTCGAAG | |

| Exon 6 | AGCCAGGCATCTCACCAT | CAGGGCCATAGAACACAATG | |

| Exon 7 | GACCCTGCTTGCACTCACTA | TCTGCTTATCCCCACAGCTT | |

| TGFBR3 | Exon 1 | TTTGAAAATTGCAAGGAGGG | CATGCTAGGAGGCCAAGAAG |

| Exon 2 | GCAGTGGTTTGATCACCCTT | AAGTTGCCCAATCCAGACAG | |

| Exon 3 | TTCTTTGGCAGGGAGCTAAA | AAGCTCAGGCCACACAGAGT | |

| Exon 4 | GAATCCGCTGCTTAAAAACG | GTGATTCCTTGCCCTAACCA | |

| Exon 5 | GTCAATAGGCGGTCACTGGT | GATGAAGCACACCTGAAGCA | |

| Exon 6 | TGAAGACTTGGAAGAGGGGA | GGGTTCAGAGAGGTTAGGGG | |

| Exon 7 | TCATCGTTCTTAGCCCAAGG | CTGGAAAAGCTTCATTTGGG | |

| Exon 8 | ACACCTGCCCATTCTATGCT | GTAGGCCCATCCAACTGAGA | |

| Exon 9 | GAATTTCCAAGGCCAACAGA | TTGACAGTGCAGCCTTTGTC | |

| Exon 10–11 | GCAGAACCAAACACACATGG | GGTCTGTGAGGTAGGACAGGA | |

| Exon 12 | AAAGCAGCGTGTCATCTGAA | GGGCAGTTCCAAAACAAAAA | |

| Exon 13 | AGGTAGAGCTGGTGAAGGCA | GAATGCAAGGGAGAGTGACC | |

| Exon 14 | AGTTTAGGTGTTTGCCTTCA | CTACCTTCCCATTCAAGCCA | |

| Exon 15 | GAATCTTCATTGCATTCTCCG | TTCACCAACATCACAATCGC | |

| Exon 16 | AGTTAAAATGGCAAATGCGG | TCATGTTTATACTAGCCCTGGG | |

| ENG | Exon 1 | TCCCTGTGTCCACTTCTCCT | CCGAGGCTTTCTTTCAACAC |

| Exon 2 | TAAGGTGGCTGTGATGATGC | TCAGCTCTTCCCACCTGAGT | |

| Exon 3 | TGGAAGCATCCAAATCATCA | CATCAACCTGACTCCCACCT | |

| Exon 4 | GGCTGATCTGACTGCTAGGG | GATATTTGGTGGAGGAGCCA | |

| Exon 5 | CCACCACTATCTTTGGCTGT | GGCTTTATAAGGGACCGGAG | |

| Exon 6 | CTCCGGTCCCTTATAAAGCC | CCTTGCCCAAGCTCACA | |

| Exon 7 | AACCCAAACTCCCAACCTCT | ATCTTGGCTCACTGCAACCT | |

| Exon 8 | GGGCACACAGTGATCACACA | CCACATCTTACTGTGCCACG | |

| Exon 9–10 | CTGGGTTGTGGTCAGTCCTT | CATTCCAGACACACATGGCT | |

| Exon 11 | GAGTCAGGCAACTCCACAGG | AAGAGTTCCCACCCCTGAGT | |

| Exon 12 | TGCTCAGGGACACTGACAAG | AGGCCACATGCCTGATTAAG | |

| Exon 13 | AGTGTTCACAAGGGTGAGGG | CTAGGCTGCTATGGCTCTGG | |

| Exon 14–15 | TTCAGAGAAGTCGAGGGTCC | TGAGTTCACACCAGTGCTCC | |

| ACVR1 | Exon 1 | TGAATGGCAGTTTGAAGGTG | CTCCCAAAGTGCTGGGATTA |

| Exon 2 | TCATGGTTGATGGTGATGCT | CCAGGGTGACCTTCCTTGTA | |

| Exon 3 | TGTGTGGTCAGGATCAGGAG | GGGAAGACTACACAGGTGCC | |

| Exon 4 | GGTTGCAGTGAACCCAGATT | TCTCTCATCATCCCAAAGGG | |

| Exon 5 | GGGCAGCTTCCACCTTATTT | CAAAACGGAGAGAGCAAAGG | |

| Exon 6 | CCTCTTAGGGCAATTGGTCA | AACATGTTGTGGGGGAGAGA | |

| Exon 7 | AGTGACCCTGGATCCACAAG | AATGGCTGGTCTCTTCCAGA | |

| Exon 8 | ATTGCCTTTTTCTCCCACCT | AGATCCACGGGACAGATCAC | |

| Exon 9 | CCAATCTGGCCTATGTCGTT | AGCGAGGTTAGGGTGGTTTT | |

| B. Oligonucleotides used for restriction digestion analysis | |||

| TGFBR3 | Exon 3 | TCTGTTGATAGTGAGTTGCAAAAA | ACACCCGGTAGCCAGTTACA |

| Exon 14 | AGTTTAGGTGTTTGCCTTCA | CTACCTTCCCATTCAAGCCA | |

| Exon 15 | TCTTCATTGCATTCTCCGATT | TTTTGTGAAACCCAATTTATACCA | |

| ENG | Exon 1 | GCGTCCCTGTGTCCACTT | CCGAGGCTTTCTTTCAACAC |

| Exon 2 | AATCCATGGAACGAATATAATGA | AGACCCTGCCCCTAGAAATG | |

| Exon 14 | AGGCCTTGGCTGTGATGAG | GCTGCTCAGTCTCTCCTGCT | |

Restriction Digestion Analysis

For probands containing novel variants, amplified exons were digested with restriction enzymes. DNA samples from General Population I were used as negative control. PCR reactions were performed using rTth polymerase system (GeneAmpXL Kit, Applied Biosystems). The following conditions were used to amplify the TGFBR3 exon 4: 96°C, 2 min; 35 cycles of 95°C, 20 sec; 60°C, 30 sec; 72°C, 30 sec; and a final 72°C, 5 min. The same conditions were used for the other exons, except that annealing temperatures were at 55°C for TGFBR3 exon 16; and 55°C and 65°C for ENG exons 2 and 14, respectively. PCR products were digested with Hph I (TGFBR3 exon 4), Bsr DI (TGFBR3 exon 16), Mwo I (ENG exon 2) or Stu I (ENG exon 14) (New England Biolabs). Digestion products were visualized in agarose gels. To confirm ENG p.R205W and p.R232W which did not alter a restriction site, independent re-sequencing reactions were performed.

Testing association of Novel Variants with IA

To test the association of novel variants with IA, allelic frequencies were analyzed in cases (familial or sporadic groups) versus individuals from General Population I. Variants were genotyped by sequencing, restriction digestion or by using a MassARRAY genotyping system (Sequenom). Variants detected by restriction digestion were verified by sequencing. P-values were calculated with Fisher’s exact test with Bonferroni correction.

Testing association of previously identified SNPs with IA

To further test the association of TGF-β pathway genes with IA, allelic frequencies of selected known SNPs in TGFB1, TGFBR1, TGFBR2, ACVR1, TGFBR3 or ENG were compared between cases and reference populations. To avoid population stratification issues, only Caucasian subjects were included in the analyses. We compared a case group of 31 familial probands from the original 44 (77% female and 23% male; ages 28–92 years, average 58 years) against two reference groups, one with 150 Caucasian individuals from General Population I (54% female and 46% male; unknown ages) and the other with 60 unrelated Caucasian HapMap subjects from the International HapMap Project (http://www.hapmap.org/) (50% female and 50% male; unknown ages). These HapMap samples were derived from U.S. residents with northern and western European ancestry collected by the Centre d'Etude du Polymorphisme Humain (CEPH). Genotyping and association testing were done as described above.

Alignment of protein sequences

Information on endoglin and betaglycan protein sequences in humans and in mouse, rat, dog, cow, chicken, zebrafish, pig and orangutan was obtained from the NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) and ENSEMBL (http://www.ensembl.org/index.html) genome browsers. Protein sequences were aligned using the MegAlign program.

Results

TGFB1, TGFBR1, TGFBR2, ACVR1, TGFBR3 and ENG were directly sequenced in 44 familial IA patients using intron-based, exon-specific primers. A total of 85 variants, including single nucleotide substitutions, deletions and insertions were identified, mostly located in closely-flanking intronic regions (Appendix Table).

Seven novel coding region variants were identified, two of which were silent amino acid substitutions in TGFB1 and ACVR1. The remaining 5 were non-synonymous substitutions in ENG and TGFBR3 (Table 2). No novel variant was detected in TGFBR1 or TGFBR2. Furthermore, none of the TGFBR1 or TGFBR2 mutations previously reported MFS, LDS or TAAD was detected in these patients.

Table 2.

Novel Variants in Familial IA Patients

| DNA Sequence Trace | Minor Allele Frequency |

Fisher’s Exact P-value† |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Ex* | Variant | Codon Change |

Patient ID |

Control | Variant | Fam IA (nm/nchr)* |

Spor IA (nm/nchr)* |

GPI (nm/nchr)* |

Fam IA vs GPI* |

Spor IA vs GPI* |

| ENG | 2 | c.179– 180CC>AA (p.A60E) |

GCC- GAA |

MG02961 MG03052 |

0.023 (2/88) |

0.000 (0/182) |

0.000 (0/892) |

0.0080 | |||

| 5 | c.613C>T (p.R205W) |

CGG- TGG |

MG02707 | 0.011 (1/88) |

0.000 (0/184) |

0.000 (0/482) |

0.1544 | ||||

| 14 | c.1759C>T (p.L587F) |

CTC- TTC |

MG02637 | 0.011 (1/88) |

0.000 (0/182) |

0.001 (1/892) |

0.1716 | ||||

| TGFBR3 | 4 | c.334T>A (p.W112R) |

TGG- AGG |

MG02982 | 0.011 (1/88) |

0.000 (0/184) |

0.000 (0/900) |

0.0891 | |||

| 16 | c.2368A>T (p.I790F) |

ATT- TTT |

MG03371 | 0.011 (1/88) |

0.005 (1/184) |

0.003 (3/872) |

0.3197 | 0.1423 | |||

Ex, exon; Fam, familial; Spor, sporadic; GPI, general population I; nm, occurrence of minor allele; nchr, number of chromosomes

Significant P-value after Bonferroni correction < 0.010

Novel non-synonymous variants were genotyped in a group of individuals without known intracranial disease. ENG p.L587F and TGFBR3 p.I790F were found in 1/892 and 3/872 chromosomes, respectively, whereas ENG p.A60E, ENG p.R205W and TGFBR3 p.W112R were not detected in these individuals (Table 2). These variants were also genotyped in 92 sporadic IA patients, where TGFBR3 p.I790F was detected in 1/184 chromosomes. Allele frequency data suggest that p.A60E is significantly associated with IA in familial cases but not with IA in sporadic cases.

Sequence analyses of ENG and TGFBR3 in sporadic cases revealed another novel variant in ENG, p.R232W, which was detected in one case (0.55% allele frequency). However, it was also detected in 3 of 480 control chromosomes (0.63%).

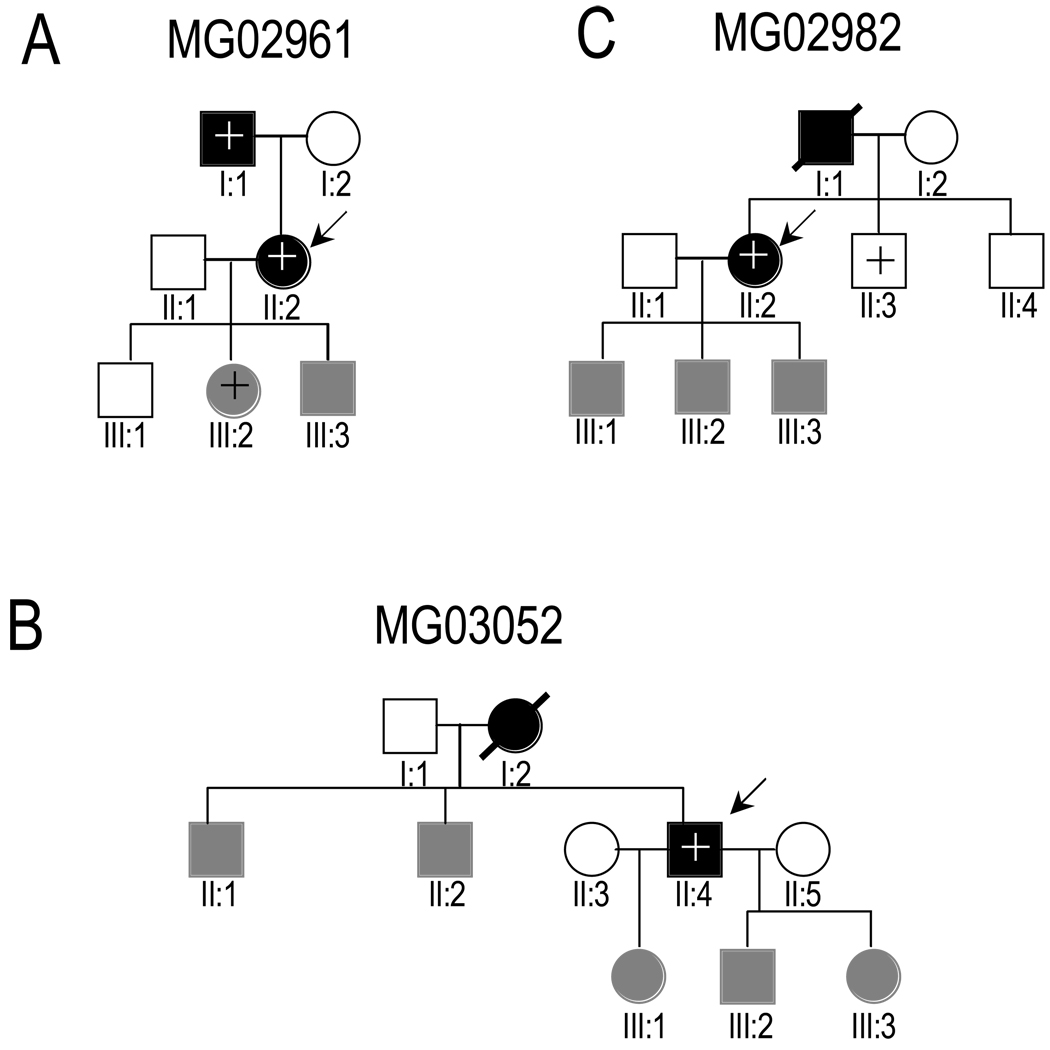

Families with p.A60E, p.R205W or p.W112R were genotyped and clinically screened for IA. In pedigree MG02707, p.R205W was absent in the proband’s affected son, and is, therefore, not disease-causing (data not shown). Unfortunately, we are unable to show whether p.A60E or p.W112R co-segregates with the IA phenotype due to the limited number of affected individuals and family members who are willing to participate (Figure 1A–C).

Figure 1.

Pedigrees of families with ENG p.A60E (A and B) or TGFBR3 p.W112R (C). Arrows indicate probands. IA-affected, unaffected and clinically unscreened individuals are indicated by blackened, open and grayed symbols, respectively. Presence or absence of the variant, determined by sequencing or restriction digestion analysis, is indicated by + or −, respectively.

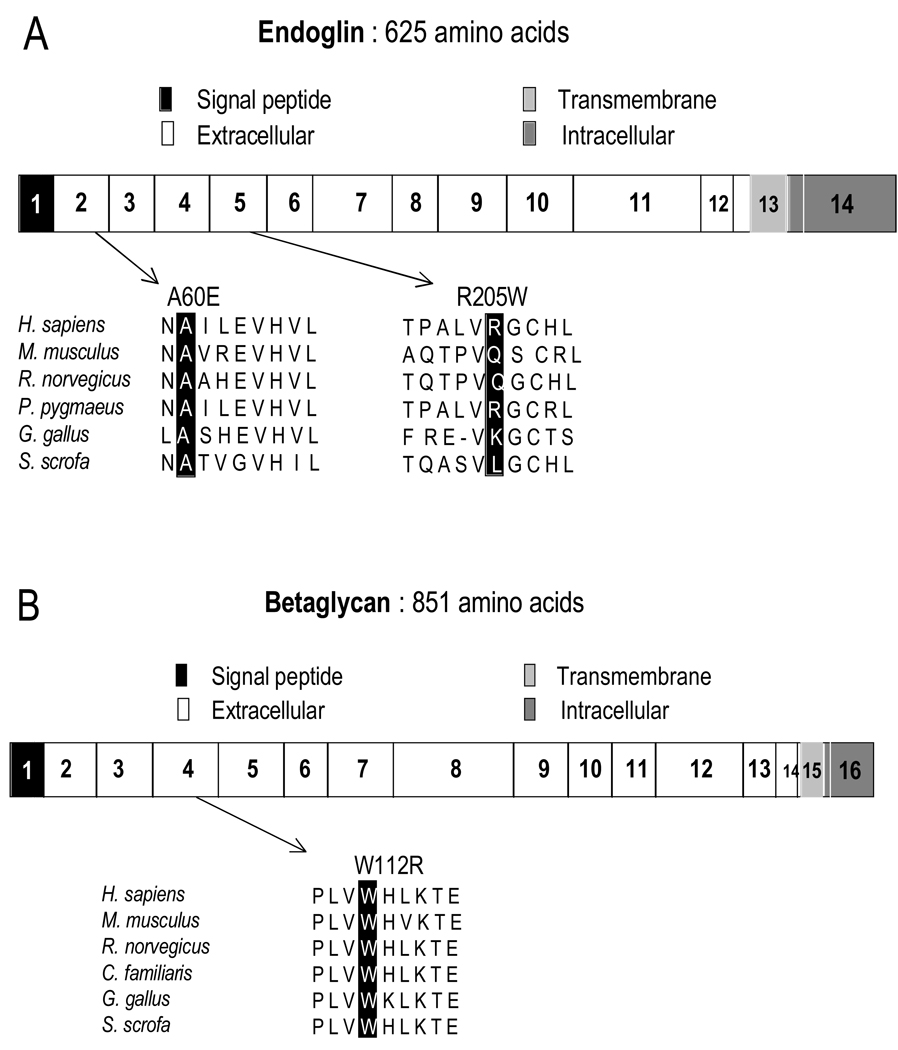

Sequence analyses of human ENG/endoglin and TGFBR3/betaglycan proteins showed that alanine 60 in endoglin is evolutionarily conserved and is located in the N-terminal region of the protein’s extracellular domain (Figure 2A). In p.A60E, a neutral alanine is replaced by a larger, highly-charged glutamate residue. Similarly, tryptophan 112 in betaglycan is highly conserved and is located in this protein’s extracellular domain, particularly in a characterized TGF-β binding site (Figure 2B). In p.W112R, a hydrophobic tryptophan is replaced by a hydrophilic arginine residue. To assess the effect of ENG p.A60E and TGFBR3 p.W112R, we applied the web-based tool Polyphen (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph/), which was developed to predict whether a missense variant is likely to affect protein structure and function. Based on sequence annotation and alignment, p.A60E was predicted as “possibly damaging” (PSIC score difference: 1.623) and p.W112R as “probably damaging” (PSIC score difference: 3.543).

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of human endoglin (A) and betaglycan (B) genes. Variants are shown in relation to exons (numbered) and domain organization. Accession numbers, Endoglin: H.sapiens NP_000109; M.musculus, NP_031958; R.norvegicus, NP001010968; P.pygmaeus, CAH92389; G.gallus, AAT84715; S.scrofa, NP_999196. Betaglycan: H.sapiens, NP_003234; M.musculus, AAC28564; R.norvegicus, NP_058952; C.familiaris, XP_547284; G.gallus, NP_989670; S.scrofa, NP_999437.

Allele frequencies of a subset of previously identified SNPs in TGFB1, TGFBR1, TGFBR2, ACVR1, TGFBR3 and ENG were analyzed in cases versus individuals without known intracranial disease (Table 3). P-values less than 0.05 were obtained for rs1155705 (TGFBR2) and rs1146031 (ACVR1). However, after applying Bonferroni correction, P-values were not statistical significant.

Table 3.

Allele Frequencies of Known SNPs in IA patients versus the General Population

| Minor Allele Frequency | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | SNP ID | Location | Variation M/m* |

Familial IA (nm/nchr)† |

Reference Population (nm/nchr)† |

Fisher’s Exact P-value |

| A. Using General Population I as reference population‡ | ||||||

| TGFBR1 | rs7861780 | EX 6 | A/C | 0.015 (1/66) | 0.000 (0/296) | 0.1823 |

| TGFBR2 | rs11466512 | INT 4 | T/A | 0.288 (19/66) | 0.279 (83/298) | 0.8804 |

| rs2228048 | EX 5 | C/T | 0.045 (3/66) | 0.017 (5/298) | 0.1614 | |

| TGFBR3 | rs1805109 | 5’UTR | G/A | 0.106 (7/66) | 0.065 (19/294) | 0.2891 |

| rs17881268 | INT 2 | C/T | 0.000 (0/66) | 0.034 (10/298) | 0.2190 | |

| rs1805113 | EX 13 | T/C | 0.439 (29/66) | 0.393 (117/298) | 0.4908 | |

| rs284878 | EX 14 | C/T | 0.045 (3/66) | 0.047 (14/300) | 1.0000 | |

| rs17882828 | EX 15 | G/C | 0.030 (2/66) | 0.003 (1/298) | 0.0859 | |

| ENG | rs7847860 | INT 2 | G/T | 0.076 (5/66) | 0.064 (19/298) | 0.7834 |

| Ref 32 | INT 7 | -/GGGGGA | 0.242 (16/66) | 0.168 (49/292) | 0.1602 | |

| rs3739817 | EX 8 | C/T | 0.091 (6/66) | 0.070 (21/298) | 0.6031 | |

| rs1800956 | EX 8 | G/C | 0.000 (0/66) | 0.003 (1/298) | 1.0000 | |

| ACVR1 | rs2227861 | EX 5 | T/C | 0.212 (14/66) | 0.253 (75/296) | 0.5307 |

| B. Using CEPH-derived HapMap Samples as reference population§ | ||||||

| TGFB1 | rs8179181 | INT 5 | C/T | 0.242 (15/62) | 0.339 (40/118) | 0.2333 |

| TGFBR1 | rs334354 | INT 7 | G/A | 0.258 (16/62) | 0.217 (26/120) | 0.5793 |

| rs868 | 3’UTR | A/G | 0.258 (16/62) | 0.217 (26/120) | 0.5793 | |

| TGFBR2 | rs1155705 | INT 3 | A/G | 0.172 (10/58) | 0.317 (38/120) | 0.0482 |

| TGFBR3 | rs1805109 | 5’UTR | G/A | 0.097 (6/62) | 0.085 (10/118) | 0.7880 |

| rs1805110 | EX 2 | C/T | 0.097 (6/62) | 0.092 (11/120) | 1.0000 | |

| rs2810904 | EX 3 | G/A | 0.274 (17/62) | 0.336 (39/116) | 0.4983 | |

| rs4658261 | INT 10 | G/A | 0.145 (9/62) | 0.178 (21/118) | 0.6761 | |

| rs4658260 | INT 10 | C/T | 0.145 (9/62) | 0.175 (21/120) | 0.6776 | |

| rs1805113 | EX 13 | T/C | 0.435 (27/62) | 0.508 (60/118) | 0.4328 | |

| rs2296621 | INT 14 | C/A | 0.210 (13/62) | 0.250 (30/120) | 0.5856 | |

| rs1805115 | 3’UTR | G/A | 0.177 (11/62) | 0.217 (26/120) | 0.5669 | |

| ENG | rs3739817 | EX 8 | C/T | 0.097 (6/62) | 0.075 (9/120) | 0.5845 |

| rs1330684 | INT 12 | G/A | 0.387 (24/62) | 0.325 (39/120) | 0.4157 | |

| rs10760503 | INT 14 | T/C | 0.435 (27/62) | 0.379 (44/116) | 0.5216 | |

| ACVR1 | rs1146031 | EX 8 | A/G | 0.113 (7/62) | 0.017 (2/120) | 0.0080 |

M, major allele; m, minor allele

nm, occurrence of minor allele;. nchr, number of chromosomes

Significant P-value after Bonferroni correction < 0.003846

Significant P-value after Bonferroni correction < 0.003125

Discussion

Mutations in TGF-β receptors, TGFBR1 and TGFBR2, are associated with thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections (TAADs). Previously, we reported that IA and AA segregate in a subset of families and are likely inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion. In this study, we tested the hypothesis that IA and AA share a common genetic basis in some families. Specifically, we hypothesized that mutations affecting TGF-β signaling might also play a role in IA pathogenesis. We sequenced 44 familial IA patients to identify variants in the TGFB1 ligand, signaling receptors and co-receptors. No novel missense variants were found in TGFBR1 and TGFBR2. Furthermore, none of the previously identified mutations associated with TAAD were detected, suggesting that mutations in TGFBR1 and TGFBR2 are not a major cause of IA development. However, novel variants were identified in ENG/endoglin and TGFBR3/betaglycan in a small subset of patients.

Endoglin and betaglycan are transmembrane proteins that modulate TGF-β-mediated cellular responses. They have large extracellular domains and serine/threonine-rich cytoplasmic regions. The importance of endoglin in vessel wall structural development has been demonstrated by defective vasculature and lethality in an endoglin knockout mouse model. In humans, endoglin mutations are associated with hemorrhagic telangiectasia 1 (HHT1), an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by altered vascular development resulting to capillary telangiectasias and arteriovenous malformations of the skin, lung, liver, gastrointestinal tract and brain. With the recognized role of endoglin in TGF-β signaling, it is thought that abnormal vessel development in HHT1 is due to abnormal TGF signaling during vascular development25. At present, there are more than one hundred endoglin mutations identified in HHT1 patients, all involving the extracellular domain, including deletions (∼33%), missense (20%), insertions (∼16%), nonsense (∼15%), splice site mutations (∼13%), and indels (∼3%)26. In most cases, these mutations lead to unstable transcripts and reduced levels of functional mutant proteins, suggesting that haploinsufficiency is the major underlying mechanism for HHT126. In some HHT cases, additional vascular complications may arise, such as aneurysms in various organs, including the brain27. In our study, we identified a novel ENG variant (p.A60E) that has not been described in HHT.

Betaglycan has been implicated in various developmental processes. Knockout mouse models demonstrate a defect in coronary vasculogenesis 28 and in heart and liver development 29. In humans, betaglycan has been implicated in tumor suppression and ovarian function regulation30, 31. The novel betaglycan variant we noted, p.W112R, has not been described previously. Both betaglycan p.W112R and endoglin p.A60E affect highly conserved residues and were absent in hundreds of reference samples tested, suggesting their importance in protein function. However, studies involving additional affected families and functional analyses are needed to elucidate their role in specific role IA pathogenesis.

The role of endoglin in IA susceptibility has been tested by other investigators and conflicting results have been reported. A 6-base insertion polymorphism in endoglin showed association with IA in a Japanese population 32, but this result could not be replicated in a Caucasian, Korean and another Japanese population 33–35. SNP rs1800956 showed association with IA in a Korean population35, but not in a Japanese population34. In our study, both polymorphisms failed to associate with IA. These results suggest that endoglin, like TGFBR1 and TGFBR2, is not a major IA susceptibility gene. However, it is possible that elucidation of the effects of variants can shed light on the pathogenetic mechanisms underlying IA formation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (7K23RR016186 to D.H.K.).

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

None

References

- 1.Ruigrok YM, Rinkel GJ. Genetics of intracranial aneurysms. Stroke. 2008;39:1049–1055. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.497305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim DH, Van Ginhoven G, Milewicz DM. Incidence of familial intracranial aneurysms in 200 patients: Comparison among caucasian, african-american, and hispanic populations. Neurosurgery. 2003;53:302–308. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000073418.34609.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wills S, Ronkainen A, van der Voet M, Kuivaniemi H, Helin K, Leinonen E, Frosen J, Niemela M, Jaaskelainen J, Hernesniemi J, Tromp G. Familial intracranial aneurysms: An analysis of 346 multiplex finnish families. Stroke. 2003;34:1370–1374. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000072822.35605.8B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ronkainen A, Hernesniemi J, Ryynanen M. Familial subarachnoid hemorrhage in east finland, 1977–1990. Neurosurgery. 1993;33:787–796. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199311000-00001. discussion 796–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kojima M, Nagasawa S, Lee YE, Takeichi Y, Tsuda E, Mabuchi N. Asymptomatic familial cerebral aneurysms. Neurosurgery. 1998;43:776–781. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199810000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bromberg JE, Rinkel GJ, Algra A, Greebe P, van Duyn CM, Hasan D, Limburg M, ter Berg HW, Wijdicks EF, van Gijn J. Subarachnoid haemorrhage in first and second degree relatives of patients with subarachnoid haemorrhage. Bmj. 1995;311:288–289. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7000.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakajima H, Kishi H, Yasui T, Komiyama M, Iwai Y, Yamanaka K, Nishikawa M. Intracranial aneurysms in identical twins. Surg Neurol. 1998;49:306–308. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(97)00184-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schievink WI, Schaid DJ, Rogers HM, Piepgras DG, Michels VV. On the inheritance of intracranial aneurysms. Stroke. 1994;25:2028–2037. doi: 10.1161/01.str.25.10.2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim DH, Van Ginhoven G, Milewicz DM. Familial aggregation of both aortic and cerebral aneurysms: Evidence for a common genetic basis in a subset of families. Neurosurgery. 2005;56:655–661. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000156787.55281.53. discussion 655–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Milewicz DM, Chen H, Park ES, Petty EM, Zaghi H, Shashidhar G, Willing M, Patel V. Reduced penetrance and variable expressivity of familial thoracic aortic aneurysms/dissections. Am J Cardiol. 1998;82:474–479. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00364-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Norrgard O, Angqvist KA, Fodstad H, Forssell A, Lindberg M. Co-existence of abdominal aortic aneurysms and intracranial aneurysms. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1987;87:34–39. doi: 10.1007/BF02076012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barbour JR, Spinale FG, Ikonomidis JS. Proteinase systems and thoracic aortic aneurysm progression. J Surg Res. 2007;139:292–307. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2006.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bruno G, Todor R, Lewis I, Chyatte D. Vascular extracellular matrix remodeling in cerebral aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 1998;89:431–440. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.89.3.0431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hara A, Yoshimi N, Mori H. Evidence for apoptosis in human intracranial aneurysms. Neurol Res. 1998;20:127–130. doi: 10.1080/01616412.1998.11740494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thompson RW, Liao S, Curci JA. Vascular smooth muscle cell apoptosis in abdominal aortic aneurysms. Coron Artery Dis. 1997;8:623–631. doi: 10.1097/00019501-199710000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chyatte D, Bruno G, Desai S, Todor DR. Inflammation and intracranial aneurysms. Neurosurgery. 1999;45:1137–1146. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199911000-00024. discussion 1146–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He R, Guo DC, Estrera AL, Safi HJ, Huynh TT, Yin Z, Cao SN, Lin J, Kurian T, Buja LM, Geng YJ, Milewicz DM. Characterization of the inflammatory and apoptotic cells in the aortas of patients with ascending thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;131:671–678. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loeys BL, Schwarze U, Holm T, Callewaert BL, Thomas GH, Pannu H, De Backer JF, Oswald GL, Symoens S, Manouvrier S, Roberts AE, Faravelli F, Greco MA, Pyeritz RE, Milewicz DM, Coucke PJ, Cameron DE, Braverman AC, Byers PH, De Paepe AM, Dietz HC. Aneurysm syndromes caused by mutations in the tgf-beta receptor. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:788–798. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mizuguchi T, Collod-Beroud G, Akiyama T, Abifadel M, Harada N, Morisaki T, Allard D, Varret M, Claustres M, Morisaki H, Ihara M, Kinoshita A, Yoshiura K, Junien C, Kajii T, Jondeau G, Ohta T, Kishino T, Furukawa Y, Nakamura Y, Niikawa N, Boileau C, Matsumoto N. Heterozygous tgfbr2 mutations in marfan syndrome. Nat Genet. 2004;36:855–860. doi: 10.1038/ng1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pannu H, Fadulu VT, Chang J, Lafont A, Hasham SN, Sparks E, Giampietro PF, Zaleski C, Estrera AL, Safi HJ, Shete S, Willing MC, Raman CS, Milewicz DM. Mutations in transforming growth factor-beta receptor type ii cause familial thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections. Circulation. 2005;112:513–520. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.537340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh KK, Rommel K, Mishra A, Karck M, Haverich A, Schmidtke J, Arslan-Kirchner M. Tgfbr1 and tgfbr2 mutations in patients with features of marfan syndrome and loeys-dietz syndrome. Hum Mutat. 2006;27:770–777. doi: 10.1002/humu.20354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Habashi JP, Judge DP, Holm TM, Cohn RD, Loeys BL, Cooper TK, Myers L, Klein EC, Liu G, Calvi C, Podowski M, Neptune ER, Halushka MK, Bedja D, Gabrielson K, Rifkin DB, Carta L, Ramirez F, Huso DL, Dietz HC. Losartan, an at1 antagonist, prevents aortic aneurysm in a mouse model of marfan syndrome. Science. 2006;312:117–121. doi: 10.1126/science.1124287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen MM., Jr Tgf beta/smad signaling system and its pathologic correlates. Am J Med Genet A. 2003;116A:1–10. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.10750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ignotz RA, Massague J. Transforming growth factor-beta stimulates the expression of fibronectin and collagen and their incorporation into the extracellular matrix. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:4337–4345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Begbie ME, Wallace GM, Shovlin CL. Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (osler-weber-rendu syndrome): A view from the 21st century. Postgrad Med J. 2003;79:18–24. doi: 10.1136/pmj.79.927.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abdalla SA, Letarte M. Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia: Current views on genetics and mechanisms of disease. J Med Genet. 2006;43:97–110. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.030833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kamiyama K, Okada H, Niizuma H, Higuchi H. [a case report: Osler-weber-rendu disease with cerebral aneurysm, cerebral arteriovenous malformation and pulmonary arteriovenous fistula (author's transl)] No Shinkei Geka. 1981;9:67–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Compton LA, Potash DA, Brown CB, Barnett JV. Coronary vessel development is dependent on the type iii transforming growth factor beta receptor. Circ Res. 2007;101:784–791. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.152082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stenvers KL, Tursky ML, Harder KW, Kountouri N, Amatayakul-Chantler S, Grail D, Small C, Weinberg RA, Sizeland AM, Zhu HJ. Heart and liver defects and reduced transforming growth factor beta2 sensitivity in transforming growth factor beta type iii receptor-deficient embryos. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:4371–4385. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.12.4371-4385.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chand AL, Robertson DM, Shelling AN, Harrison CA. Mutational analysis of betaglycan/tgf-betariii in premature ovarian failure. Fertil Steril. 2007;87:210–212. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.05.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Finger EC, Turley RS, Dong M, How T, Fields TA, Blobe GC. Tbetariii suppresses non-small cell lung cancer invasiveness and tumorigenicity. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:528–535. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takenaka K, Sakai H, Yamakawa H, Yoshimura S, Kumagai M, Nakashima S, Nozawa Y, Sakai N. Polymorphism of the endoglin gene in patients with intracranial saccular aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 1999;90:935–938. doi: 10.3171/jns.1999.90.5.0935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krex D, Ziegler A, Schackert HK, Schackert G. Lack of association between endoglin intron 7 insertion polymorphism and intracranial aneurysms in a white population: Evidence of racial/ethnic differences. Stroke. 2001;32:2689–2694. doi: 10.1161/hs1101.098660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Onda H, Kasuya H, Yoneyama T, Hori T, Nakajima T, Inoue I. Endoglin is not a major susceptibility gene for intracranial aneurysm among japanese. Stroke. 2003;34:1640–1644. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000075770.70554.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Joo SP, Lee JK, Kim TS, Kim MK, Lee IK, Seo BR, Kim JH, Kim SH, Oh CW. A polymorphic variant of the endoglin gene is associated with increased risk for intracranial aneurysms in a korean population. Surg Neurol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2008.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]