Summary

Leishmania chagasi, transmitted mainly by Lutzomyia longipalpis sand flies, causes visceral leishmaniasis and atypical cutaneous leishmaniasis in Latin America. Successful vector control depends upon determining vectorial capacity and understanding Leishmania transmission by sand flies. As microscopic detection of Leishmania in dissected sand fly guts is laborious and time-consuming, highly specific, sensitive, rapid and robust Leishmania PCR assays have attracted epidemiologists’ attention. Real-time PCR is faster than qualitative PCR and yields quantitative data amenable to statistical analyses. A highly reproducible Leishmania DNA polymerase gene-based TaqMan real-time PCR assay was adapted to quantify Leishmania in sand flies, showing intra-assay and inter-assay coefficient variations lower than 1 and 1.7%, respectively, and sensitivity to 10 pg Leishmania DNA (∼120 parasites) in as much as 100 ng sand fly DNA. Data obtained for experimentally infected sand flies yielded parasite loads within the range of counts obtained by microscopy for the same sand fly cohort or that were around five times higher than microscopy counts, depending on the method used for data analysis. These results highlight the potential of quantitative PCR for Leishmania transmission studies, and the need to understand factors affecting its sensitivity and specificity.

Keywords: Leishmania, Sand fly, PCR, Sensitivity and specificity, Transmission, Epidemiology

1. Introduction

The leishmaniases are a set of diseases caused by Leishmania parasites, which affect more than 2 million people in over 88 tropical and Mediterranean countries. Resistance to first- and second-line chemotherapy, particularly in regions of intense Leishmania transmission, has been reported (Mittal et al., 2007). Leishmania parasites are transmitted to sylvatic or peridomestic mammalian reservoir hosts and to humans by blood-feeding female sand flies.

Leishmania real-time PCR assays for estimating relative loads within vertebrate hosts have been developed, based upon Leishmania small ribosomal subunit, DNA polymerase or glucose-6 phosphatase genes (Bossolasco et al., 2003, Bretagne et al., 2001, Mary et al., 2004, Nicolas et al., 2002, Wortmann et al., 2001). These PCR studies have indicated that Leishmania load influences clinical outcome and that low levels of parasitaemia or clearance are associated with either cure or fewer relapses in HIV–Leishmania co-infection. In canine leishmaniasis, the quantity of Leishmania DNA correlates with parasite density in the bone marrow, blood, skin or urine, and often with severity of clinical symptoms (Manna et al., 2006, Solano-Gallego et al., 2007). Furthermore, Svodová et al. (2003) demonstrated Le. tropica transmission to its Phlebotomus sergenti sand fly vector from asymptomatic ‘reservoir’ black rats using quantitative PCR. Thus, real-time PCR offers a feasible approach to follow Leishmania infection time course, parasite clearance and tissue tropism.

Natural infection rates in sand flies are traditionally estimated by microscopic identification of Leishmania within dissected sand fly guts and/or parasite isolation from dissected sand flies in vitro or in vivo. However, these methods are time- and labour-consuming, especially when considering the low infection prevalence found in most endemic foci (Ashford et al., 1991). A number of Leishmania-DNA-based PCR assays, with differing sensitivities and specificities, have been applied to studies of sand fly natural infection rates (Aransay et al., 2000, Córdoba-Lanús et al., 2006). Leishmania species typing through RFLPs, hybridisation or sequencing of amplified Leishmania DNA, with species-specific PCR primers, has also been reported (Azizi et al., 2006, Garcia et al., 2007, Jorquera et al., 2005, Martin-Sánchez et al., 2006).

Two drawbacks of end-point, compared with real-time, PCR are that the former is only qualitative and that it is still time-consuming, as PCR cycling time adds to the time required for visualisation of PCR products run in agarose gels. In real-time PCR assays, the PCR products are ‘visualised’ in real time and are also quantifiable, allowing statistical testing of the reproducibility and significance of results obtained. Furthermore, although initially more costly (i.e. for equipment and reagents), than end-point PCR, real-time PCR is significantly less time-demanding, reducing the overall research cost in the long term.

It is important to quantify Leishmania in sand flies to evaluate relative Leishmania development efficiencies between different sand fly species that transmit the same parasite species. These differences may account for vectorial capacity differences, which in turn could contribute to observed epidemiological differences between visceral leishmaniasis foci (Montoya-Lerma et al., 2003). It is also recognised that one major difference between natural and experimental infections is that the true parasite infective dose probably consists of 1–1000 metacyclics in natural conditions but several million in experimental infections (Rogers et al., 2004, Warburg and Schlein, 1986). Consequently, real-time PCR would allow more accurate determination of natural infection doses. Numerous reports have established that effective parasite dose egested at the vertebrate host biting site determines antigen concentration and distribution, and these in turn influence the timing and type of immune responses and hence clinical outcome (Lira et al., 2000). However, to date there are no published studies in which Leishmania load has been estimated within sand flies using as accurate a method as real-time PCR (Gómez-Saladín et al., 2005). This article reports the application of a TaqMan real-time PCR assay to quantify Leishmania within sand flies based on the Le. infantum single copy DNA polymerase α and the Lutzomyia longipalpis periodicity genes.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Leishmania and sand fly maintenance

Lutzomyia longipalpis sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) from Jacobina, Bahia State, Brazil, were reared at 22–27 °C, 60–70% relative humidity and 12:12 (L:D) photoperiod, as described by Modi and Tesh (1983). Newly emerged flies were fed on 70% (w/v) sucrose solution ad libitum before processing for DNA extraction. Leishmania infantum (MHOM/BE/67/ITMAP263), a reference strain used in other PCR assay development studies (Noyes et al., 1996), was selected to develop the real-time PCR assay within sand flies. Promastigotes were cultured in HOMEM at 26 °C as described (Berens et al., 1976).

2.2. Sand fly experimental infection

Female Lu. longipalpis sand flies (∼125 flies in a cage, 5 d after mating) were fed on fresh rabbit blood seeded with Le. infantum amastigotes (2 × 106/ml) through a chick skin membrane feeding apparatus (Rogers et al., 2002). Amastigotes were obtained from Le. infantum-infected BALB/c mouse spleen homogenates in M199 medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, B and E vitamins (Gibco, Invitrogen Corp., Paisley, UK) and 25 μg/ml gentamycin sulphate (Sigma-Aldrich Co., Cambridge, UK) at pH 7.2. To prevent premature mortality, flies were allowed to defecate onto filter paper inside the cage but were prevented from laying eggs by continuous saturated sucrose feeding and by withdrawing oviposition substrates. Twelve infected flies [13 d post-infection to allow metacyclogenesis (Rogers and Bates, 2007)] were dissected and parasite numbers were estimated by microscopic examination of gut homogenates using a haemocytometer, as detailed by Rogers et al. (2002). Six infected flies from the same infection cohort were individually stored in 2 ml 96% (v/v) ethanol at room temperature, and were used for Leishmania quantitation by real-time PCR.

2.3. DNA isolation

Cultured Leishmania promastigotes (108) were washed in buffered saline before DNA isolation, as described by Campos-Ponce et al. (2005). Individual female sand flies were placed onto 3MM Whatmann filter paper to allow the ethanol to evaporate for a few minutes before DNA extraction. An SDS-potassium acetate method (Collins et al., 1987) was used (average yield per fly obtained: 2040 ng DNA). DNA concentrations and enrichment relative to protein were determined at 260/280 nm in a Biophotometer (Eppendorf UK, Cambridge, UK). Sand fly samples were tested for amplification with microsatellite LIST MS6-001 PCR primers (GenBank accession no. AF411613; see Table 1), before storage at 4 °C.

Table 1.

Qualitative and quantitative PCR primers and conditions

| Target | Forward primera | Reverse primera | Probea | Conditions | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leishmania | KDNA 120 bp | CCTATTTTACACCAACCCCCAGT | GGGTAGGGGCGTTCTGCGAAA | End-point PCR | 1.25 mmol/l MgCl2; 1 min, 94 °C; 40 cycles – 30 s, 94 °C + 30 s, 58 °C + 30 s, 72 °C | Nicolas et al., 2002 |

| DNA polymerase α 90 bp | TGTCGCTTGCAGACCAGATG | GCATCGCAGGTGTGAGCAC | 5′-FAMCAGCAACAACTTCGAGCCTGGCACC-3′-TAMRA | 3 mmol/l MgCl2; 5 min, 95 °C; 50 cycles – 15 s, 95 °C + 1 min, 65 °C | Bretagne et al., 2001 | |

| Lu. longipalpis | MSLIST6001 150 bp | AAAGGGTGCGAAGTTATTGC | GGGTGGGTTGGACATTCTAC | End-point PCR | 2.5 mmol/l MgCl2; 1 min, 95 °C; 6 cycles – 30 s, 95 °C + 30 s, 53 °C + 45 s, 72 °C; 26 cycles – 30 s, 92 °C + 30 s, 53 °C + 55 s, 72 °C; 30 min, 72 °C | Watts et al., 2001 |

| periodicity 80 bp | ATTTCTTTTCCTTAGGACCATCGA | TAGGACATCTTCGGAAAATTGTTG | 5′-AMTCCTCASAGTCTTTGCATCCACGTTGGTT-3′-TAMRA | 3 mmol/l MgCl2; 5 min, 95 °C; 50 cycles – 15 s, 95 °C + 1 min, 65 °C | Bauzer et al., 2002 | |

DNA sequences are given in the standard 5′–3′ direction.

2.4. Qualitative PCR

End-point PCR was visualised on ethidium-bromide-stained 1.75% (w/v) wide range agarose (50–1000 bp; Sigma-Aldrich) gels to test whether isolated DNA was amplifiable and to determine the robustness, specificity, relative amplification efficiencies and lack of cross-inhibition of real-time PCR primers. Serial dilutions of Leishmania and/or sand fly DNA (100 ng–1 pg), were amplified with 100 pm PCR primers in 75 mmol/l Tris-HCl (pH 8 at 25 °C), 20 mmol/l (NH4)2SO4, 0.01% (v/v) Tween-20, 200 μM each deoxynucleotide triphosphate (dNTP), 1.25 units Thermoprime plus DNA Polymerase (Reddymix, ABgene, Epsom, UK) and optimum MgCl2 concentration in a final volume of 10 μl.

PCR primers suitable for TaqMan probe real-time PCR based on the Lu. longipalpis periodicity (per) gene sequence (GenBank accession no. AF446142; Bauzer et al., 2002) were designed using the Primer Express 2.0 software (Perkin-Elmer, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Other sand fly and Leishmania PCR primers used with PCR/cycle conditions, amplicon sizes and sources are listed in Table 1.

2.5. Quantitative real-time PCR

Leishmania DNA polymerase primers described by Bretagne et al. (2001) and newly designed sand fly per primers were independently optimised for relative primer and magnesium concentration using 100 ng Le. infantum DNA and 250 nmol/l Leishmania TaqMan probe or sand fly per TaqMan probe, respectively, in an Applied Biosystems ABIPRISM 7000 amplification and fluorescence detection system. Optimised 20 μl PCR reactions contained 900 nmol/l each of the appropriate forward/reverse primer pair, 250 nmol/l Leishmania or sand fly TaqMan probe, 10 μl Universal TaqMan master mix (catalog 4304437, Applied Biosystems), and either 10-fold serial dilutions (100 ng–1 pg) of Leishmania DNA or sand fly DNA, 10-fold dilutions Leishmania DNA spiked over a fixed amount of sand fly DNA (100 ng) or DNA (average 130 ng per fly) from an experimentally infected sand fly. Reactions were pre-incubated at 50 °C for 2 min for uracyl-N-glycosylase activation, followed by denaturation/DNA polymerase activation at 95 °C for 10 min, and 40 amplification cycles, each of 15 s at 95 °C plus 1 min at 60 °C. Four independent assays were run on different days, each consisting of Leishmania DNA polymerase and Lu. longipalpis triplicate samples separately amplified in a single PCR plate. Negative (no template) controls, cross-amplification controls (Leishmania primers on 100 ng sand fly DNA and sand fly primers on 100 ng Leishmania DNA), and positive controls (100 ng Leishmania or Lu. longipalpis DNA), were included in each reaction plate.

2.6. Data analysis and statistical methods

The real-time PCR detection threshold was set at 10 times the standard deviation above the mean baseline fluorescence calculated from 2–12 cycles in the exponential phase. For each sample, mean fractional cycle numbers corresponding to the first amplification above the threshold value (threshold cycle, Ct) were used to obtain separate standard negative linear regression curves. Mean Ct values were plotted against the logarithm (base 10) of the DNA quantity of Le. infantum DNA polymerase and Lu. longipalpis per genes.

Input Leishmania DNA polymerase gene copy numbers were obtained using the absolute quantification method by interpolation of sample mean Ct values in the Leishmania DNA polymerase amplification standard curve. Reproducibility of the results was assessed through estimations of mean values, SDs and intra-assay and inter-assay variation coefficients (from raw Ct values) for four (Leishmania DNA polymerase) or five (sand fly per) independent repeat runs. One of the samples consisting of equal amounts of sand fly and Leishmania DNA (corresponding to 100 ng of each DNA) was used as control in a comparative method that related Leishmania DNA polymerase PCR signals to Lu. longipalpis per gene PCR signals (as reference) taking into account the efficiencies of both PCR primer sets. The following equation for obtaining the ratio relative to the amount of Leishmania DNA in the control (R) was used:

where E is the amplification efficiency obtained from the linear regression standard curve using E = 10−1/slope (Pfaffl, 2001).

Conversion of DNA amounts to Leishmania parasites, based on the size of the sequenced Leishmania major haploid genome (33.6 MB, 72.5 fg for its diploid genome) plus an estimated ∼15% kDNA (∼10.9 fg) yielded ∼83.4 fg total DNA for a single parasite. Based on these considerations, 10 pg Leishmania DNA represents ∼120 Leishmania parasites in this report.

3. Results

3.1. Specificity, sensitivity and reproducibility of the assays

Despite copy number differences, when tested by qualitative PCR, Leishmania DNA polymerase and kinetoplast origin primers (listed in Table 1) displayed similar sensitivity and specificity in amplifying an expected single product only in the presence of Leishmania DNA (10 pg to 100 ng) (Supplementary Figure 1). Lutzomyia longipalpis DNA (100 ng) did not interfere with Leishmania DNA polymerase gene amplification (water or sand fly DNA alone were negative) (Supplementary Figure 2A). Lutzomyia longipalpis per primers also showed similar specificity and sensitivity, producing the expected 80 bp product when tested by end-point PCR (Supplementary Figure 2B; data not shown).

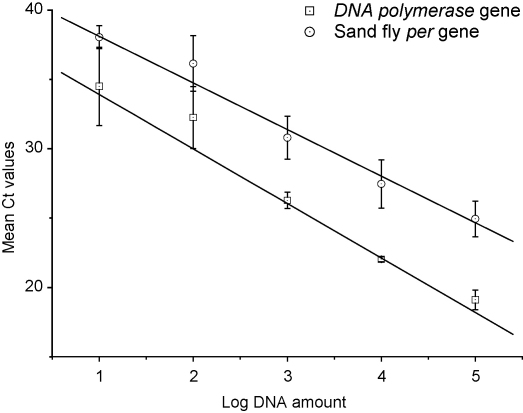

Figure 1 shows the sensitivity of the real-time PCR assays (10 pg, 105 range), defined as the lowest DNA amount yielding amplification signals in all three replicates. This sensitivity was similar to that shown by qualitative PCR when tested using serial dilutions of Leishmania or Lu. longipalpis DNA of known concentrations determined by spectrophotometry (compare Figure 1 with Supplementary Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Standard curves for quantification of Leishmania DNA polymerase and Lutzomyia longipalpis periodicity gene input copies. ( ) Mean Leishmania DNA polymerase Ct values ± 1 SD from independent experiments of three replicates of 10-fold serial dilutions of Le. infantum DNA in molecular biology grade (MBG) water, tested on different days, were plotted against the logarithm of the DNA amount (100 ng to 10 pg per reaction). Slope = –4.101; intercept = 39.139; r2 = 0.9821; efficiency = 10−1/slope = 1.7533. (

) Mean Leishmania DNA polymerase Ct values ± 1 SD from independent experiments of three replicates of 10-fold serial dilutions of Le. infantum DNA in molecular biology grade (MBG) water, tested on different days, were plotted against the logarithm of the DNA amount (100 ng to 10 pg per reaction). Slope = –4.101; intercept = 39.139; r2 = 0.9821; efficiency = 10−1/slope = 1.7533. ( ) Mean Lu. longipalpis per Ct values ± 1 SD from five independent experiments of three replicates of 10-fold serial dilutions of sand fly DNA in MBG water, tested on different days, were plotted against the logarithm of the DNA amount (100 ng to 10 pg per reaction). Slope = –3.486; intercept = 41.936; r2 = 0.9799; efficiency = 10−1/slope = 1.93581. Ct: the cycle number at which fluorescence rises significantly above the background fluorescence.

) Mean Lu. longipalpis per Ct values ± 1 SD from five independent experiments of three replicates of 10-fold serial dilutions of sand fly DNA in MBG water, tested on different days, were plotted against the logarithm of the DNA amount (100 ng to 10 pg per reaction). Slope = –3.486; intercept = 41.936; r2 = 0.9799; efficiency = 10−1/slope = 1.93581. Ct: the cycle number at which fluorescence rises significantly above the background fluorescence.

The reproducibility of both real-time PCR assays was tested running triplicate samples with standard curve dilutions, and controls on the same plate and on different days. The SDs obtained for the standard curves (per gene 0.83–2.01; DNA polymerase gene 0.18–2.82) are shown in Figure 1. Table 2 lists the inter-assay variation coefficients (0.01–0.11%) for Leishmania detection in the presence and absence of sand fly DNA. High amounts of sand fly and Leishmania DNA (100 ng each; see Table 2) appeared to inhibit amplification, whereas highly diluted Leishmania/sand fly DNA samples (10–100 pg; see Table 2) resulted, mostly, in Leishmania DNA overestimations, (especially for Leishmania/sand fly mixed samples). Determinations within the Leishmania 10–10 000 pg range in Leishmania-spiked 100 ng sand fly DNA samples were more consistent with optical-density-derived Leishmania DNA amounts than those for Leishmania/sand fly mixed DNA samples (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Reproducibility of quantification of Leishmania in sand fly DNA samples

| Le. infantum DNA/pga | Mean Ct ± SD |

Inter-assay variation coefficient | Estimated Leishmania DNA (pg)e |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leishmaniab | Leishmania-spiked sand fly DNAc | Leishmania–sand fly mixed DNAd | Leishmania-spiked sand fly DNA | Leishmania–sand fly mixed DNA | ||

| 10 | 34.50 ± 2.82 | 33.67 ± 0.20 | 29.83 ± 0.20 | 0.08 | 22 | 186 |

| 100 | 32.26 ± 2.23 | 32.45 ± 0.33 | 26.65 ± 0.12 | 0.11 | 43 | 1110 |

| 1000 | 26.28 ± 0.58 | 25.89 ± 0.10 | 24.48 ± 0.15 | 0.04 | 1700 | 3750 |

| 10 000 | 22.03 ± 0.18 | 21.67 ± 0.08 | 21.78 ± 0.62 | 0.01 | 18 200 | 17 100 |

| 100 000 | 19.11 ± 0.70 | 19.33 ± 0.11 | 20.28 ± 0.41 | 0.03 | 67 700 | 39 700 |

Ct: threshold cycle value, the cycle corresponding to the first noticeable fluorescence rise above the background fluorescence.

DNA amount in 10-fold serial dilutions from a 100 ng/μl stock determined by spectrophotometry.

Mean Ct values from four independent runs each of triplicate samples of 10-fold serially diluted DNA in molecular biology grade (MBG) water.

Mean Ct values from one run of triplicate samples of 10-fold serially diluted DNA spiked onto 100 ng sand fly DNA samples.

Mean Ct values from one run of triplicate samples of 10-fold serially diluted solution containing equal amounts of Leishmania and sand fly DNA.

Mean Ct values (columns c and d) were related to a standard curve constructed with the mean Ct values for Leishmania DNA serially diluted in MBG water (Figure 1).

3.2. Estimation of Leishmania parasite loads in experimentally infected sand flies

Results obtained by real-time PCR using both the standard curve absolute quantification method and a relative quantification method to estimate the number of Leishmania parasites in experimentally infected sand flies are shown in Table 3. Low intra-assay variation coefficients were estimated for the sand fly per (0.0003–0.001%) and the Leishmania DNA polymerase (0.0004–0.005%) genes (see Table 3). Parasite number estimates based on the standard curve (see Figure 1) for the Leishmania DNA polymerase gene (six flies; mean 103 642; range 25 739–167 306) were three times higher than those obtained by microscopic examination of dissected gut homogenates of separate sand flies from four similarly infected cohorts (12 flies; mean 75 435; range 600–330 330) (Supplementary Table 1). Leishmania loads per fly calculated by the Pfaffl (2001) relative quantification method were five times higher than those obtained using the absolute standard curve method (six flies; mean 574 547; range 130 694–1 497 239) (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Quantification of Leishmania in experimentally infected Lutzomyia longipalpis sand flies

| Sand fly number | Sand fly periodicitya |

Leishmania DNA polymeraseb |

Leishmania parasites/flyc |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Ct ± SD | Intra-assay variation coefficient | Mean Ct ± SD | Intra-assay variation coefficient | Absolute methodd | Relative methode | |

| 1 | 26.59 ± 0.03 | 0.001 | 27.10 ± 0.06 | 0.002 | 160 778 | 1 497 239 |

| 2 | 25.67 ± 0.06 | 0.002 | 30.36 ± 0.02 | 0.0004 | 25 739 | 130 694 |

| 3 | 25.38 ± 0.06 | 0.002 | 28.11 ± 0.03 | 0.0008 | 91 207 | 381 810 |

| 4 | 25.61 ± 0.01 | 0.0003 | 28.78 ± 0.17 | 0.005 | 62 670 | 305 078 |

| 5 | 25.32 ± 0.06 | 0.002 | 27.71 ± 0.10 | 0.003 | 114 149 | 459 405 |

| 6 | 25.32 ± 0.03 | 0.002 | 27.03 ± 0.02 | 0.0007 | 167 306 | 673 054 |

Ct: threshold cycle value, the cycle corresponding to the first noticeable fluorescence rise above the background fluorescence.

Lu. longipalpis per gene real-time PCR.

Le. infantum DNA polymerase α gene real-time PCR.

It was estimated that one parasite contained ∼83.4 fg total DNA.

Mean Ct values for Leishmania DNA polymerase amplification in infected flies (b), were related to the mean Ct values (four independent experiments) obtained for 10-fold serially diluted Leishmania DNA in molecular biology grade (MBG) water (Figure 1).

The method developed by Pfaffl (2001) was used. Mean Ct values for Leishmania DNA polymerase gene amplification in infected flies (b) were related to mean Ct values for sand fly per gene (a), and to the Leishmania DNA polymerase and sand fly per PCR signals obtained for a sample containing 100 ng sand fly and 100 ng Leishmania DNA used as control.

4. Discussion

Leishmania quantification by PCR yields copies of the target template input that the researcher can relate to parasite counts based on: (1) the number of target gene copies present in the Leishmania genome; (2) the accuracy of determination of Leishmania DNA or parasite numbers by an independent method; (3) sample factors, including total and target DNA concentration and presence of inhibitors; and (4) the assumed DNA amount per Leishmania parasite. The Leishmania assay used in the present study simplifies the stoichiometry between Leishmania parasite numbers and copies of target gene input to 1:1 as it is based on the single copy DNA polymerase α gene. In addition, amplification measurements based on hybridisation of an internal TaqMan probe provided assay specificity. Prior to quantitative PCR, PCR primers including the newly designed reference Lu. longipalpis periodicity primers for relative quantification were optimised by qualitative end-point PCR for efficiency, specificity and sensitivity.

The present assay showed intra- and inter-assay variation coefficients either lower than or comparable to Leishmania PCR assays reported (Bretagne et al., 2001, Manna et al., 2006, Nicolas et al., 2002, Wortmann et al., 2001). Indeed, high reproducibility was maintained despite the relatively poor accuracy of DNA amount estimates for low DNA concentrations determined by optical density and PCR depression observed at high sample DNA concentrations. Owing to different PCR protocols and DNA per parasite estimations, sensitivities reported for the different Leishmania quantitative assays are generally not directly comparable. For example, Nicolas et al. (2002) reported detection of 0.1 parasite based on the assumption of 1 ng total DNA per Leishmania parasite, whereas it equates to less than 0.1 ng (∼84.3 fg) in the present study.

Mean Leishmania parasite numbers obtained by the absolute quantification method were consistent with parasite counts obtained by standard microscopic counting methods for infected sand flies from the same cohort. Parasite counts ∼8-fold higher than those observed by light microscopy were obtained using the Pfaffl (2001) relative quantification method based on the Lu. longipalpis per gene. However, it should be acknowledged that: (1) comparison between quantitative PCR and microscopy estimates for the same individual fly would have been more accurate; (2) further real-time replicate infected sand fly samples would increase the reliability of the assay; and (3) the efficiencies of Leishmania DNA polymerase and Lu. longipalpis per primers were not strictly comparable, precluding the use of the relatively simpler comparative, 2−ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). This indicates that other Leishmania/sand fly gene pairs should be explored, with emphasis on polymorphic single copy non-repetitive genes that could be also used for species identification. Further refinement of relative Leishmania quantification is worthwhile, because in contrast to the absolute quantification method, comparative methods are independent from the amount of sand fly DNA, optical density DNA concentration inaccuracies and the presence of PCR inhibitors.

Quantification of Leishmania live parasites in vertebrate host tissues using an18S rRNA-based quantitative PCR assay (QT-NASBA) with a chemiluminescent internal probe has been reported (Van der Meide et al., 2005). However, Leishmania DNA-based quantitative PCR appears to detect live parasites according to a recent multi-target real-time PCR study (Prina et al., 2007). Although the Leishmania DNA assay used in this study did not distinguish between Leishmania species or among differentiation stages within sand flies, intra-fly parasite densities obtained were consistent with those determined by other methods (Rogers et al., 2004, Warburg and Schlein, 1986). In the future, the development of a Leishmania stage-specific PCR assay would separately quantify the number of mammal-infective metacyclic and other non-infective stages within sand flies and in sand fly infective egested inoculum at the biting site. This is valuable information on the proportion of infective sand flies at any given time and on the influence of the infective inoculum size and composition on the vertebrate host's immune response. As effective parasite dose egested by sand flies at the bite site is likely to be determined by the co-evolutionary adaptive biochemistry of the association between Leishmania and sand fly genotypes, the method here described represents a first step towards the accurate estimation of metacyclogenesis rates when comparing relative vectorial efficiencies between different sibling sand fly species and in studies on Leishmania transmission mechanisms (Maingon et al., 2007, Montoya-Lerma et al., 2003, Rogers et al., 2004).

In conclusion, a highly reproducible quantitative PCR assay is described for estimating Leishmania numbers in sand flies, with intra-assay and inter-assay coefficient variations lower than 1 and 1.7%, respectively, and sensitivity down to 10 pg Leishmania DNA (∼120 parasites) in as much as 100 ng of sand fly DNA. Furthermore, estimated parasite loads within experimentally infected sand flies were within the range of counts obtained by microscopy for the same sand fly cohort or ∼five times higher than microscopy counts, depending on the method used for data analysis. These results highlight the potential of quantitative PCR and the need to further refine this powerful method for the study of natural sand fly infection rates and Leishmania transmission mechanisms.

Funding

MER and PAB were supported by the Wellcome Trust (project grants 064945 and 078937).

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Ethical approval

Not required.

Authors’ note

Results herein reported are part of the thesis on ‘Chemical and molecular studies on Leishmania manipulation of Lutzomyia longipalpis blood feeding behaviour’ submitted by SR for the award of MPhil degree by Keele University, Staffordshire, UK. SR's research was co-supervised by JGCH and RDCM.

Authors’ contributions

RDCM contributed to the experimental design and experimental work; SR produced all of the experimental work; MER and PAB contributed to the laboratory sand fly infection design and parasite counts; JGCH, MER and PAB provided experimental guidance; RDCM and SR analysed and interpreted the data; RDCM drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to and read and approved the final manuscript. RDCM, SR and JGCH are guarantors of the paper.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr Pam Taylor (Keele University) and Ms Davina Moor (Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine) for sand fly rearing. We gratefully acknowledge Dr Harry Noyes (Liverpool University), for suggesting real-time PCR comparative quantification methods and for useful discussions. The authors thank Prof. Richard Ward (Keele University) for his support to SR and helpful critique of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.04.003.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Sensitivity of (A) Leishmania kDNA and (B) DNA polymerase α gene primers. Ethidium-bromide-stained PCR products separated on 1.75% (w/v) wide range agarose gels in Tris-acetate buffer for serial 10-fold dilutions of Le. infantum DNA (lanes 2–10) using (A) kDNA or (B) DNA polymerase primers. Lane 1: 50 bp DNA ladder (MBI Fermentas); lane 2: 100 ng; lane 3: 10 ng; lane 4: 1 ng; lane 5: 100 pg; lane 6: 10 pg; lane 7: 1 pg; lane 8: 100 fg; lane 9: 10 fg; lane 10: 1 fg; lane 11: molecular biology grade (MBG) water instead of Leishmania DNA. Sizes of marker fragments in base pairs are indicated on the left. The size estimated for the major PCR band is shown by an arrow on the right.

Specificity of (A) Leishmania DNA polymerase α and (B) Lutzomyia longipalpis periodicity gene primers. Ethidium-bromide-stained PCR products separated on 1.75% (w/v) wide range agarose gels in Tris-acetate buffer alongside a 50 bp DNA ladder (Fermentas); lane 1 in both panels. (A) PCR with Leishmania DNA polymerase primers. Lanes 2–11: serial 10-fold dilutions of Le. infantum DNA (100 ng to 0.1 fg, respectively; each serial dilution contained 100 ng sand fly DNA); lane 12: molecular biology grade (MBG) water instead of Leishmania DNA; lane 13: 100 ng sand fly DNA. (B) PCR with Lu. longipalpis per primers. Lane 2: 100 ng sand fly DNA; lane 4: 100 ng Leishmania DNA; lane 5: 100 ng each Leishmania and sand fly DNA; lane 6: MBG water no template control; lane 3: 100 ng sand fly DNA with MS 6-001 primers. Sizes of marker fragments in base pairs are indicated on the left. The size estimated for the major PCR band is shown by an arrow on the right.

References

- Aransay A.M., Scoulica E., Tselentis Y. Detection and identification of Leishmania DNA within naturally infected sand flies by seminested PCR on minicircle kinetoplastic DNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000;66:1933–1938. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.5.1933-1938.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashford R.W., Desjeux P., de Raadt P. Estimation of population at risk of infection with leishmaniasis. Immunol. Today. 1991;8:104–105. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(92)90249-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azizi K., Rassi Y., Javadian E., Motazedian M.H., Rafizadeh S., Yaghoobi E.M.R., Mohebali M. Phlebotomus (Paraphlebotomus) alexandri: a probable vector of Leishmania infantum in Iran. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 2006;100:63–68. doi: 10.1179/136485906X78454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauzer L.G., Souza N.A., Ward R.D., Kyriacou C.P., Peixoto A.A. The period gene and genetic differentiation between three Brazilian populations of Lutzomyia longipalpis. Insect Mol. Biol. 2002;11:315–323. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2002.00340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berens R.L., Brun R., Krassner S.M. A simple monophasic medium for axenic culture of hemoflagellates. J. Parasitol. 1976;62:360–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossolasco S., Gaiera G., Olchini D., Gulletta M., Martello L., Bestetti A., Bossi L., Germagnoli L., Lazzarin A., Uberti-Foppa C., Cinque P. Real-time PCR assay for clinical management of human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with visceral leishmaniasis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003;41:5080–5084. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.11.5080-5084.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretagne S., Durand R., Olivi M., Garin J.-F., Sulahian A., Rivollet D., Vidaud M., Deniau M. Real-time PCR as a new tool for quantifying Leishmania infantum in liver in infected mice. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 2001;8:828–831. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.8.4.828-831.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos-Ponce M., Ponce C., Ponce E., Maingon R.D.C. Leishmania chagasi/infantum: further investigations on Leishmania tropisms in atypical cutaneous and visceral leishmaniasis foci in Central America. Exp. Parasitol. 2005;109:209–216. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2004.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins F.H., Mendez M.A., Rasmussen M.O., Mehaffey P.C., Besansky N.J., Finnerty V. A ribosomal RNA probe differentiates member species of the Anopheles gambiae complex. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1987;37:37–41. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1987.37.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Córdoba-Lanús E., Lizarralde de Grosso M., Piñero J.E., Valladares B., Salomón O.D. Natural infection of Lutzomyia neivai with Leishmania spp. in North Western Argentina. Acta Trop. 2006;98:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia A.L., Tellez T., Parrado R., Rojas E., Bermudez H., Dujardin J.C. Epidemiological monitoring of American tegumentary leishmaniasis: molecular characterization of a periodomestic transmission cycle in the Amazonian lowlands of Bolivia. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2007;101:1208–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Saladín E., Doud C.W., Maroli M. Short report: surveillance of Leishmania spp. among sand flies in Sicily (Italy) using a fluorogenic real-time polymerase chain reaction. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2005;72:138–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorquera A., González R., Marchán-Marcano E., Oviedo M., Matos M. Multiplex-PCR for detection of natural Leishmania infection in Lutzomyia spp. captured in an endemic region for cutaneous leishmaniasis in State of Sucre, Venezuela. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 2005;100:45–48. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762005000100008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lira R., Doherty M., Modi G., Sacks D. Evolution of lesion formation, parasite load, immune response, and reservoir potential in C57BL/6 mice following high- and low-dose challenge with Leishmania major. Infect. Immun. 2000;68:5176–5182. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.9.5176-5182.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K.J., Schmittgen T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCt method. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maingon R.D.C., Ward R.D., Gordon J., Hamilton C., Bauzer L.G., Peixoto A.A. The Lutzomyia longipalpis species complex: does population sub-structure matter to Leishmania transmission? Trends Parasitol. 2007;24:12–17. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna L., Reale S., Viola E., Vitale F., Manzillo V.F., Michele P.L., Caracappa S., Gravino A.E. Leishmania DNA load and cytokine expression levels in asymptomatic naturally infected dogs. Vet. Parasitol. 2006;142:271–280. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Sánchez J., Gállego M., Barón S., Castillejo S., Morillas-Marquez F. Pool screen PCR for estimating the prevalence of Leishmania infantum infection in sandflies (Diptera: Nematocera, Phlebotomidae) Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2006;100:527–532. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mary C., Faraut F., Lascombe L., Dumon H. Quantification of Leishmania infantum DNA by a real-time PCR assay with high sensitivity. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004;42:5249–5255. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.11.5249-5255.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal M.K., Rai S., Ashutosh, Ravinder, Gupta S., Sundar S., Goyal N. Characterization of natural antimony resistance in Leishmania donovani isolates. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2007;76:681–688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modi G.B., Tesh R.B. A simple technique for mass rearing Lutzomyia longipalpis and Phlebotomus papatasi (Diptera: Psychodidae) in the laboratory. J. Med. Entomol. 1983;20:568–569. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/20.5.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montoya-Lerma J., Cadena H., Oviedo M., Ready P.D., Barazarte R., Travi B.L., Lane R.P. Comparative vectorial efficiency of Lutzomyia evansi and Lu. longipalpis for trnasmitting Leishmania chagasi. Acta Trop. 2003;85:19–29. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(02)00189-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolas L., Prina E., Lang T., Milon G. Real-time PCR for detection and quantitation of Leishmania in mouse tissues. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2002;40:1666–1669. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.5.1666-1669.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noyes H.A., Belli A.A., Maingon R. Appraisal of various random amplified polymorphic DNA-polymerase chain reaction primers for Leishmania identification. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1996;55:98–105. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.55.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl M.W. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:2002–2007. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prina E., Roux E., Mattei D., Milon G. Leishmania DNA is rapidly degraded following parasite death: an analysis by microscopy and real-time PCR. Microbes Infect. 2007;9:1307–1315. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers M.E., Bates P.A. Leishmania manipulation of sand fly feeding behavior results in enhanced transmission. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e91. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers M.E., Chance M.L., Bates P.A. The role of the promastigote secretory gel in the origin and transmission of the infective stage of Leishmania mexicana by the sand fly Lutzomyia longipalpis. Parasitology. 2002;124:495–507. doi: 10.1017/s0031182002001439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers M.E., Ilg T., Nikolaev A.V., Fergusson M.A., Bates P.A. Transmission of cutaneous leishmaniasis by sand flies is enhanced by regurgitation of fPPG. Nature. 2004;430:463–467. doi: 10.1038/nature02675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solano-Gallego L., Rodriguez-Cortes A., Trotta M., Zampieron C., Razia L., Furlanello T., Caldin M., Roura X., Arberola J. Detection of Leishmania infantum DNA by FRET-based real-time PCR in urine from dogs with natural clinical leishmaniosis. Vet. Parasitol. 2007;147:315–319. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2007.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svodová M., Votýpka J., Nicolas L., Wolf P. Leishmania tropica in the black rat (Rattus rattus): persistence and transmission from asymptomatic host to sand fly vector Phlebotomus sergenti. Microbes Infect. 2003;5:361–364. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(03)00046-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Meide W.F., Schoone G.J., Faber W.R., Zeegelaar J.E., de Vries H.J., Özbel Y., Lai A., Fat R.F., Coelho L.I., Kassi M., Schallig H.D. Quantitative nucleic acid sequence-based assay as a new molecular tool for detection and quantification of Leishmania parasites in skin biopsy samples. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005;43:5560–5566. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.11.5560-5566.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warburg A., Schlein Y. The effect of post-blood-meal nutrition of Phlebotomus papatasi on the transmission of Leishmania major. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1986;35:926–930. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1986.35.926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts P.C., Boyland E., Noyes H.A., Maingon R.D.C., Kemp S.J. Polymorphic dinucleotide microsatellite loci in the sand fly Lutzomyia longipalpis (Diptera: Phlebotominae) Mol. Ecol. 2001:60–61. Notes 2. [Google Scholar]

- Wortmann G., Sweeney C., Houng H.S., Aronson N., Stiteler J., Jackson J., Ockenhouse C. Rapid diagnosis of leishmaniasis by fluorogenic polymerase chain reaction. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2001;65:583–587. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2001.65.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Sensitivity of (A) Leishmania kDNA and (B) DNA polymerase α gene primers. Ethidium-bromide-stained PCR products separated on 1.75% (w/v) wide range agarose gels in Tris-acetate buffer for serial 10-fold dilutions of Le. infantum DNA (lanes 2–10) using (A) kDNA or (B) DNA polymerase primers. Lane 1: 50 bp DNA ladder (MBI Fermentas); lane 2: 100 ng; lane 3: 10 ng; lane 4: 1 ng; lane 5: 100 pg; lane 6: 10 pg; lane 7: 1 pg; lane 8: 100 fg; lane 9: 10 fg; lane 10: 1 fg; lane 11: molecular biology grade (MBG) water instead of Leishmania DNA. Sizes of marker fragments in base pairs are indicated on the left. The size estimated for the major PCR band is shown by an arrow on the right.

Specificity of (A) Leishmania DNA polymerase α and (B) Lutzomyia longipalpis periodicity gene primers. Ethidium-bromide-stained PCR products separated on 1.75% (w/v) wide range agarose gels in Tris-acetate buffer alongside a 50 bp DNA ladder (Fermentas); lane 1 in both panels. (A) PCR with Leishmania DNA polymerase primers. Lanes 2–11: serial 10-fold dilutions of Le. infantum DNA (100 ng to 0.1 fg, respectively; each serial dilution contained 100 ng sand fly DNA); lane 12: molecular biology grade (MBG) water instead of Leishmania DNA; lane 13: 100 ng sand fly DNA. (B) PCR with Lu. longipalpis per primers. Lane 2: 100 ng sand fly DNA; lane 4: 100 ng Leishmania DNA; lane 5: 100 ng each Leishmania and sand fly DNA; lane 6: MBG water no template control; lane 3: 100 ng sand fly DNA with MS 6-001 primers. Sizes of marker fragments in base pairs are indicated on the left. The size estimated for the major PCR band is shown by an arrow on the right.