Abstract

The hippocampal formation plays a key role in novelty detection, but the mechanisms remain unknown. Novelty detection aids the encoding of new information into memory - a processes thought to depend on the hippocampal formation (HF) and to be modulated by the theta rhythm of EEG. We examined EEG recorded in the HF of rats foraging for food within a novel environment, as it became familiar over trials the next five days, and in two more novel environments unexpectedly experienced in trials interspersed with familiar trials over three more days. We found that environmental novelty produces a sharp reduction in the theta frequency of foraging rats, that this reduction is greater for an unexpected environment than for a completely novel one, and that it slowly disappears with increasing familiarity. Our results suggest that the septo-hippocampal system signals unexpected environmental change via a reduction in theta frequency. In addition, they provide evidence in support of a cholinergically-mediated mechanism for novelty detection, have important implications for our understanding of oscillatory coding within memory and the interpretation of event-related potentials, and provide indirect support for the oscillatory interference model of grid cell firing in medial entorhinal cortex.

Keywords: Hippocampus, EEG, acetylcholine, exploration, rat, associative mismatch

Introduction

Detection of novelty is crucial to the everyday life of all mammals, and is a pre-requisite for the efficient encoding of events into memory. The hippocampal formation (HF) has long been linked with novelty detection, especially where experience differs from expectation given the experimental context or other stimuli (a.k.a., “contextual” or “relational” novelty, “associative mismatch” or “comparator” processing) (Sokolov , 1963; Vinogradova, 2001; Gray & McNaughton, 2000; Honey, Watt, & Good, 1998; Aggleton & Brown, 1999; Strange, Fletcher, Henson, Friston, & Dolan, 1999; Hasselmo, Wyble, & Wallenstein, 1996; Lisman & Otmakhova, 2001; Kumaran & Maguire, 2006; Kohler, Danckert, Gati, & Menon, 2005), consistent with its role in context-dependent episodic/ declarative memory (Cohen & Eichenbaum, 1993; Squire & Zola-Morgan, 1991; O’Keefe & Nadel, 1978). The electrophysiological correlates of contextual novelty detection have been the focus of extensive experimental investigation (Knight, 1996; Grunwald, Lehnertz, Heinze, Helmstaedter, & Elger, 1998; Grunwald & Kurthen, 2006; Halgren et al., 1980; Rugg & Coles, 1995; Fried, MacDonald, & Wilson, 1997; Rutishauser, Mamelak, & Schuman, 2006; Axmacher, Mormann, Fernandez, Elger, & Fell, 2006), paralleled by intense theoretical speculation regarding the underlying electrophysiological and neuropharmacological mechanisms (Lisman & Otmakhova, 2001; Hasselmo, 2006; Gray & McNaughton, 2000; Yu & Dayan, 2005; Ranganath & Rainer, 2003; Myers et al., 1996). However, the precise mechanism of novelty detection in the HF remains elusive.

Environmental novelty is a particularly salient form of contextual novelty for foraging mammals, and the HF both represents environmental layout, via the firing of ‘place cells’ (O’Keefe & Nadel, 1978; Muller, 1996) and directs exploration of spatial alterations to environmental layout – i.e., of unexpected rearrangement or absence of objects, but not replacement of an object by a new one – (O’Keefe & Nadel, 1978; Save, Poucet, Foreman, & Buhot, 1992; Save, Buhot, Foreman, & Thinus-Blanc, 1992; Lee, Hunsaker, & Kesner, 2005). This exploration is thought to enable environmental representations to be updated (O’Keefe & Nadel, 1978), and seems to result from discrepancy between current experience and a stored (spatial) representation rather than the absolute novelty of individual stimuli. Indeed, some place cells (‘misplace’ cells) specifically fire at the location of an unexpectedly displaced or missing object (O’Keefe, 1976; Fyhn, Molden, Hollup, Moser, & Moser, 2002; Lenck-Santini, Rivard, Muller, & Poucet, 2005), but not when an object is replaced by a new one “mirroring the effects of lesions; ” (Lenck-Santini et al., 2005). In addition, a sufficiently changed environment induces rapid global ‘remapping’ of the entire place cell representation (Bostock, Muller, & Kubie, 1991; Wills, Lever, Cacucci, Burgess, & O’Keefe, 2005; Fyhn, Hafting, Treves, Moser, & Moser, 2007): producing a new attractor state in memory (Wills et al., 2005; Nakazawa et al., 2002; Leutgeb et al., 2005).

Here we examine the electroencephalogram (EEG) of rats during their initial foraging in a novel environmental setting, as it subsequently became familiar, and finally in two new environments unexpectedly encountered within the now-familiar setting. The most prominent feature of the hippocampal electroencephalogram (EEG) of foraging rats is the 7-11 Hz ‘movement-related theta’ rhythm (Vanderwolf, 1969; Kramis, Vanderwolf, & Bland, 1975). This rhythm is generated in the HF under the influence of cholinergic and GABAergic innervation from the medial septum, see (Buzsaki, 2002; O’Keefe, 2006) for reviews, and the involvement of the cholinergic septo-hippocampal system in spatial memory has long been known (Givens & Olton, 1995). In addition, empirical studies have demonstrated the importance of theta oscillations for efficient memory operations (Sederberg, Kahana, Howard, Donner, & Madsen, 2003; Jacobs, Hwang, Curran, & Kahana, 2006; Ekstrom et al., 2005; Osipova et al., 2006; Rizzuto, Madsen, Bromfield, Schulze-Bonhage, & Kahana, 2006; Mormann et al., 2005; Fell et al., 2004; McCartney, Johnson, Weil, & Givens, 2004) and there has been theoretical interest in the possible role of the theta rhythm in controlling memory encoding and retrieval, see e.g. (Lisman & Otmakhova, 2001; Hasselmo, 2006; Gray & McNaughton, 2000; Meeter, Murre, & Talamini, 2004; Borisyuk, Denham, Hoppensteadt, Kazanovich, & Vinogradova, 2001; Myers et al., 1996; Hasselmo, Bodelon, & Wyble, 2002). Accordingly we sought to examine the link between environmental novelty and theta, and we specifically set out to test the prediction of a recent model of neural firing patterns in the HF: that environmental novelty might be signaled by a drop in theta frequency (Burgess, Barry, & O’Keefe, 2007).

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Four male Lister Hooded rats, weighing 315-390g at time of surgery, were used as subjects. They were maintained on a 12:12 hour light:dark schedule (with lights off at 15:00). Food deprivation was maintained such that subjects weighed 85-90% of free feeding weight.

Electrode implantation

The surgical procedures used in this study were as previously described (Cacucci, Lever, Wills, Burgess, & O’Keefe, 2004). Briefly, rats were chronically implanted with 2 microdrives under deep anaesthesia. These microdrives allowed 4 variously-spaced tetrodes to be vertically lowered through the brain after surgery. Tetrodes were constructed from 25 μm HM-L coated platinum-iridium wire (90% / 10%, California fine wire), and were aimed at CA1 or subiculum. Coordinates for the CA1 target insertion zone were: 3.0-3.1mm posterior to bregma, 1.8-2.0 mm lateral to the midline.

Electrophysiological recording and data acquisition

Rats were allowed a week to recover post-operatively before screening sessions began. Microelectrodes were lowered towards hippocampal regions over days/weeks, and then left to stabilize before recording commenced. Electrophysiological recording techniques have been previously described(Cacucci et al., 2004). Briefly, the electrode wires were AC-coupled to unity-gain buffer amplifiers (headstage). Lightweight wires (3 meters) connected the headstage to a pre-amplifier (gain 1000). The outputs of the pre-amplifier passed through a switching matrix, and then to the filters and amplifiers of the recording system (Axona, UK). Electrodes used for EEG were located as follows; Rats 1&2, CA1 throughout; Rat 3, CA1 (days 1-4) and subiculum (thereafter); Rat 4, CA1 (days 1-3) and dentate (thereafter). (We note that theta frequency does not vary with recording location within the hippocampal formation, unlike amplitude and phase (Bullock, Buzsaki, & McClune, 1990))

EEG signals were amplified 10,000-20,000 times, band-pass filtered at 0.34-125 Hz and sampled at 250 Hz. Two arrays of small, infrared light-emitting diodes (LEDs), one array brighter and more widely projecting than the other, were attached to the rat’s head to track head position and orientation, using a video camera and tracking hardware/software (DACQ2, Axona, UK). The two arrays were positioned such that the halfway position between the two arrays was centred above the rat’s skull. Offline analysis defined this halfway position as the position of the rat (TINT, Axona, UK). Positions were sampled at 50Hz.

Screening and training procedures before the test trials

Before the period of formal recording of the test trial series, rats were screened and acclimatised to recording apparatus and rice-foraging, in a room separate from both the home cage room and the testing lab. Electrode activity was monitored over a 2-5 week period. During screening, the rat rested on a square holding platform (39 cm sides, 5 cm high ridges) containing sawdust. Rats were pre-trained in this screening room to forage for rice on a black square platform (94 cm sides, 2 cm high ridges). Each rat was given a few sessions (10-20 minutes long) of training until it had acquired the random foraging task such that it spent most of its time moving over all areas of the platform. These training procedures were done so that, as far as possible, the novelty afforded by the first exposures to Environment ‘a’ did not include non-environmental novelty associated with rice-related cues/contingencies, continuously locomoting with the headstage, and so on. Once electrodes were appropriately positioned and acclimatization complete, the rat was brought to the testing lab, and placed on a holding platform (similar to the one in the screening room), see Figure 1a. All the rats had two to three hours of exposure to the holding platform in the testing lab over one to two days before beginning the test trial series.

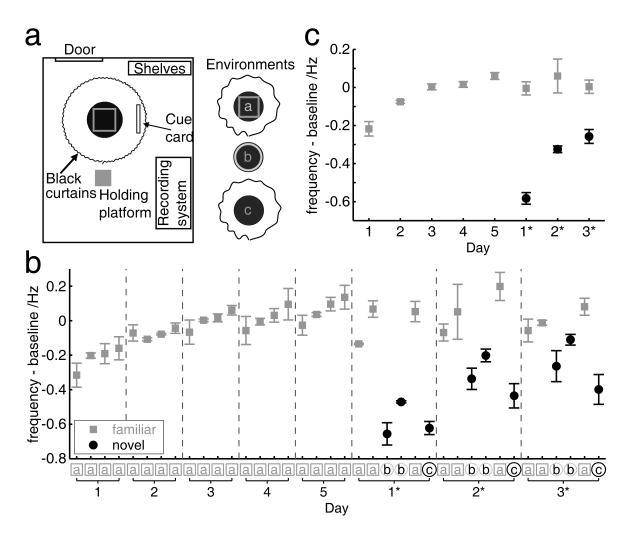

Figure 1.

Effect of novelty on theta frequency. a) Experimental set-up. b) Theta frequency increases with days of experience in environment ‘a’ (days 1-5), and change to an environment within a common setting produces an even greater initial decrease in frequency than first exposure to environment ‘a’ (cf. frequency in environments ‘b’ and ‘c’ on days 1*-3*, black points, to frequency in environment ‘a’ on days 1-3, grey points). The difference in theta frequency from ‘baseline’ (i.e. the mean frequency over days 2-5 for a given rat) is shown for each trial. c) The novelty effect is shown most clearly when each day’s trials within familiar environment ‘a’ (grey points) or novel environments ‘b’ and ‘c’ are averaged (black points). Points show the mean across rats, error bars show s.e.m.

Test trial series

A diagram of the environments used and order of testing in the test trial series is shown in Figure 1a, b. Experiments were conducted within a black-curtained circular testing arena 2.3m in diameter (except that the curtains were opened for environment ‘b’, as described below). The centre of each testing environment had the same location relative to the arena. An external white cue card (102 cm high, 77 cm wide) which was prominent in the testing arena provided directional constancy throughout the test trial series, as did standardized procedures for translating the rat and placing it into the box, and various background cues. For every trial, the rat was passively displaced, facing ‘lab north’, about 2 metres in the ‘lab north’ direction, and placed at the centre of the given environment. During trials the rat searched for grains of sweetened rice randomly thrown into the box about every 30 seconds. At the end of each trial, the rat was removed from the given recording environment, and placed back on the holding platform. Rats were kept on a holding platform outside the arena before and after every trial. The inter-trial interval was 20 minutes.

Three environments were used in the test trial series. Environment ‘a’ was a square ‘morph’ box, as previously described (Lever, Wills, Cacucci, Burgess, & O’Keefe, 2002), with 62 cm sides. The black curtains were fully drawn so as to surround environment ‘a’. Environment ‘b’ was a circular-walled, wooden light-grey enclosure, 79 cm in diameter, with ‘lab-north’ and ‘lab-south’ seams. For Environment ‘b’, the black curtains were opened, such that various extra-arena cues were visible. The ‘floor’ of Environments ‘a’ and ‘b’ was a circular black platform, raised 27 cm above the actual floor of the testing arena. Environment ‘c’ consisted simply of this circular open platform, which was 90cm in diameter, with the arena curtains fully drawn as for Environment ‘a’. The platform was thus the floor for all three environments, and was cleaned before every trial.

During the habituation phase (Days 1-5) there were 4 trials per day, all in Environment ‘a’. This was followed by the manipulation phase, on days 6, 8 and 10 (referred to as Days 1*, 2* and 3* respectively, where the asterisk indicates day within the manipulation phase). No testing was performed on days 7 and 9. There were 6 trials on Days 1*-3*, organised as follows. Trials 1, 2 and 5 were conducted in Environment ‘a’, trials 3 and 4 in Environment ‘b’, and trial 6 in Environment ‘c’. The black curtains were opened 90 seconds before the beginning of trial 3, and closed 90 seconds after the end of trial 4. We took care that testing time was similar for all rats, and similar across the test trial series for a given rat. Across all days and all rats, the starting time of the day’s first trial ranged from 2.25 pm to 4.25pm.

Recording sites and Histology

Details of EEG electrode recording sites were reconstructed using records of electrode movement, physiological markers and post-mortem histology. The rats were given an overdose of sodium pentobarbital (Lethobarb; 10 mg) and perfused transcardially with saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. The brain was sliced coronally into 40 μm thick sections, which were mounted and Cresyl-Violet Nissl-stained for visualisation of the electrode tracks/tips. See Figure 2. Physiological markers included the presence of ripple/sharp wave activity, and complex spike cell firing.

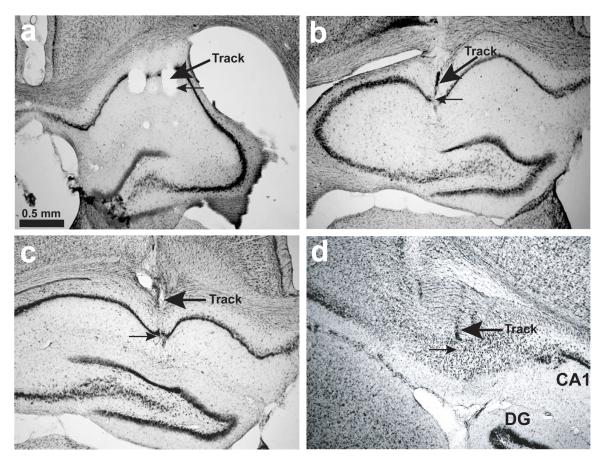

Figure 2.

Examples of EEG-electrode recording sites in anterodorsal CA1 (a, b, c) and dorsal subiculum (d), showing photomicrographs for specific rats (see Figures 3a and 4a). Thick arrows point to tissue damage and other indicators of the track made by a given tetrode. Thin arrows point to likely recording locations. The scale bar in A applies to all photomicrographs, and does not take into account tissue shrinkage. a) Location of electrode used in Rat 1 (throughout the experiment; CA1 stratum radiatum). b) Location of electrode used in Rat 2 (CA1 in/around pyramidal layer). c) Location of electrode used in Rat 3 (Days 1-4; CA1 in/around pyramidal layer). d) Location of electrode used in Rat 3 (Days 5, 1*-3*; deep subiculum).

Analysis

To restrict analysis to movement-related theta, avoiding potential behavioural confounds such as rearing, EEG data were filtered to admit only portions of EEG where the rat spent ≥ 0.5 seconds at speeds above 5 cm/s. We also re-filtered the data with an additional constraint: that the median speed in each trial was constant and equal to the median speed of the rat across all trials in the experiment k. Thus, speed limits s1 > 5 cm/s and s2 < ∞ were chosen such that the length of ordered data was symmetric (and maximal) about k. After filtering approximately half to three-quarters of the data remained for analysis.

Power spectra were calculated by finding the fast Fourier transform of the concatenated filtered data, where the square-modulus of each Fourier frequency coefficient represents the signal power at that frequency. Finally the power spectrum was smoothed using a Gaussian kernel with standard deviation 0.375Hz. Results were robust to variations in kernel size and shape. Theta frequency was taken as the frequency with peak power in the theta band (5–11Hz). All analysis was conducted using MatLab R12.1, (The MathWorks, Inc.).

To visualize systematic variation in theta frequency across rats we defined for each rat a baseline theta frequency as the mean of theta over trials in habituation days 2-5. This was subtracted from the frequency per trial in Figures 1b, 1c, 3b and 4a.

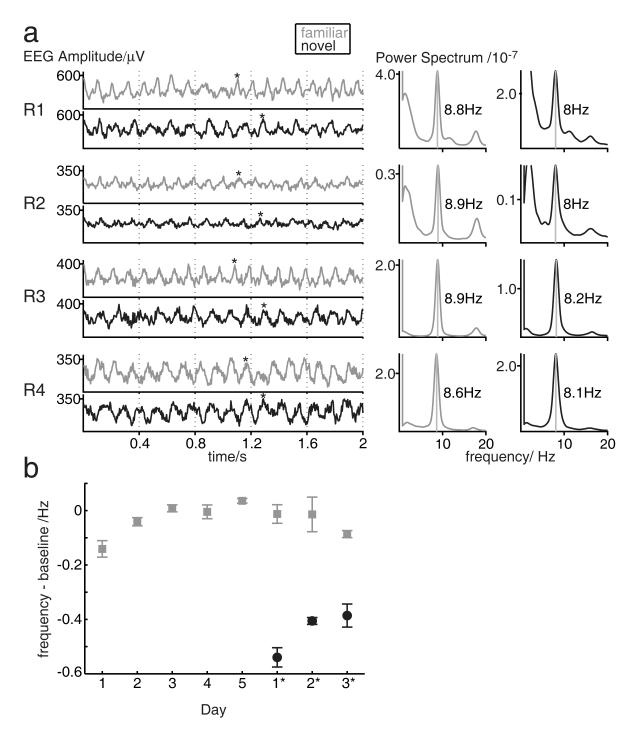

Figure 3.

Effect of novelty on theta frequency, no effect of running speed. a) Theta is visibly faster in novel environment ‘b’ (trial 3, black lines) than familiar environment ‘a’ (trial 2, grey lines) on day 1*: individual traces from each rat (left, asterisk marks 10th cycle); power spectra for whole trial (right). b) The effect of novelty on theta frequency does not reflect variations in running speed. Data from each trial were sub-sampled to remove any differences in median speed across trials in the sub-sampled data. Mean theta frequency is shown versus days of experience in familiar environment ‘a’ (grey points) or novel environments ‘b’ and ‘c’ (black points) in sub-sampled data for which median speed is constant across trials. Points show the mean across rats, error bars show s.e.m. See Supplementary Online Material for details.

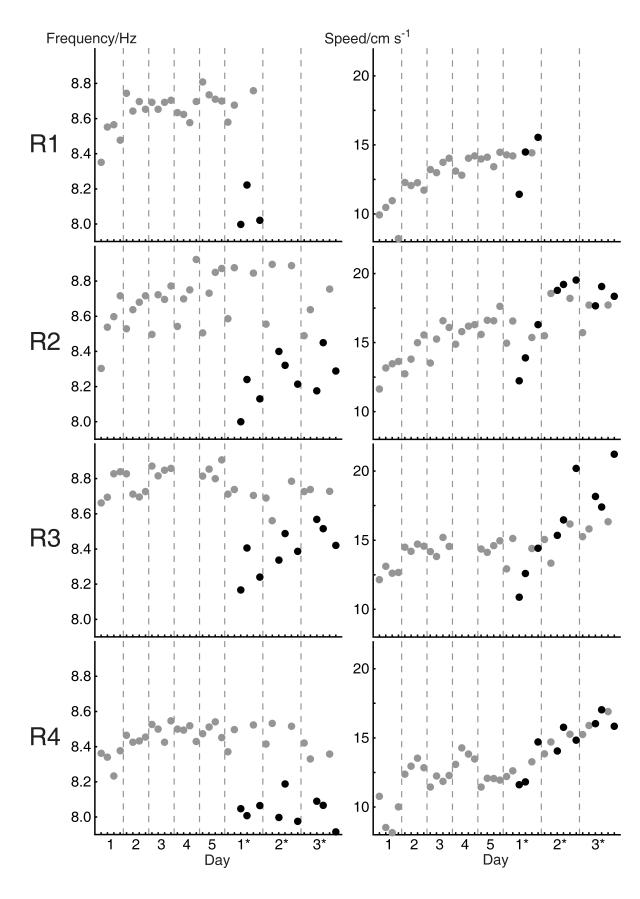

Figure 4.

Theta frequency (a) and median running speed (b) for individual rats and trials. Data from the familiar environment ‘a’ shown in grey, data from the unexpected novel environments ‘b’ and ‘c’ shown in black. See Figure 1 for details of the environments used in each trial.

Due to technical problems, EEG data were unavailable for Rat 3 on day 4. Missing values for these trials were replaced by the average over the same trials on days 2, 3 and 5 (day 1 was not included, since theta frequency was much lower on this day compared to the others). Hence, four rats were included in the ANOVA showing the effect of familiarity in days 1-5 see below. (The significant effect of day in this ANOVA remains significant if data from Rat 3 are excluded.) In addition, the test trial series for Rat 1 was terminated at the end of change day 1*, thus data for days 2* and 3* are missing for this rat. As a result, all ANOVAs involving effects over days 1*-3* only include data from the remaining 3 rats. See Figure 4 for all data.

Results

During the first 5 days of foraging in the brown square we found a progressive increase in theta frequency with increasing familiarity across days of experience (day (1-5) × trial (1-4) repeated measures ANOVA, effect of day: F4,12=24.82, p<0.001; effect of trial: n.s., p=0.26; day × trial interaction n.s., p=0.39), see Figure 1. There was a non-significant hint of an increase in theta frequency across trials within a day (Figure 1b) due largely to a strong effect in one of the rats (see Figure 4, Rat 2). In the second phase of the experiment (days 1*,2*,3*, see Figure 1), during trials in which new environments ‘b’ and ‘c’ were substituted for the expected brown square, there was a sharp decrease in theta frequency in the new environments which lessened over days (environment (new/old) × day (1*-3*) ANOVA, effect of environment: F1,2=62.10, p=0.016; effect of day: n.s., F2,4=6.51, p=0.055; day × environment interaction: F2,,4=10.27, p=0.027). The rate at which theta approached baseline in the new environments was significantly greater than that associated with the first ever trials in the brown square, with theta frequency increasing with days of exposure in both the initial environment ‘a’ and the new one ‘b’, but more so in ‘b’ (environment (b vs a) × day (1*-3* in b, 1-3 in a) × trial (1-2) ANOVA, effect of environment: F1,2=30.00, p=0.032; effect of day: F2,4=38.94, p=0.002; effect of trial n.s., p=0.147; environment × day interaction: F2,4=9.00, p=0.033).

Thus the effect of unexpectedly experiencing environments ‘b’ or ‘c’ in place of environment ‘a’ produced a greater reduction than the initial exposure to environment ‘a’, when compared to baseline, and the interaction indicates attenuation of this differential effect over days (see fig. 1b). This may reflect the need for a stronger contextual novelty signal when existing environmental representations need to be changed, i.e. when a prior expectation is violated, as compared to the effect of absolute novelty, when an environmental representation needs to be set up for the first time. Although not the focus of this paper, CA1 place cell responses were recorded from 3 of the rats on the manipulation days 1*-3*, and showed complete remapping caused by the transition from environment ‘a’ to environments ‘b’ and ‘c’, consistent with previous reports of remapping when such large changes are made to the rat’s environment (Wills et al., 2005; Fyhn et al., 2007).

The effect of environmental novelty on change days 1*-3* was visible in the raw EEG traces and immediately apparent in comparing power spectra from trials in new and familiar environments, Figure 3a (see also Figure 4). We only included EEG recorded while rats were actively foraging (moving faster than five cm/s), but our results might still reflect novelty-related changes in running speed (which has occasionally been reported to affect theta frequency, and which increases across the experiment, see Figure 4b). To test for any indirect effects of the average running speed in a trial on theta frequency, such as might be mediated by body temperature (Whishaw & Vanderwolf, 1971), we regressed median speed per trial against frequency across the entire dataset for each rat. We found non-significant effects of speed on frequency of variable strength across rats (r2 = 0.006-0.097; p=0.06-0.65 see Table 1 for details). To control for any potential effects of running speed in our analysis of the effect of novelty, we subtracted the linear effect of speed on frequency indicated by the regression analysis, and repeated the above ANOVAs on the residuals. The effect of days of experience over days 1-5 (F4,12=28.82, p<0.001) and of environmental novelty on days 1*-3* (F1,2=61.35, p=0.016) remained effectively unchanged. The greater effect of unexpected environment ‘b’ on days 1*-3* compared to novel environment ‘a’ on days 1-3 increased slightly and attenuated more slowly over days (effect of environment: F1,2=145.01, p=0.007; effect of day: F2,4=12.44, p=0.019; Environment × Day interaction: F2,4=2.56, p=0.193; effect of Trial: n.s., p=0.101).

We also calculated the theta frequency in subsets of data from each trial, chosen so that the median running speed was constant in each trial for a given rat (see Materials and Methods for more details), to control for any immediate effects of running speed on the concurrent theta frequency. These sub-sampled data are shown in Figure 3b. Similarly to the above analysis, the effect of days of experience over days 1-5 (F4,12=12.44, p<0.001), and of environmental novelty on days 1*-3* (F1,2=73.00; p=0.013) remained, with the effect of initial novelty in environment ‘a’ being slightly reduced, and the greater effect of unexpected environment ‘b’ on days 1*-3* slightly increased (F1,2=124.83, p=0.008) and showing less attenuation over days (Environment × Day interaction: F2,4=0.33, p=0.738; effect of Trial: n.s., p=0.30; no other significant interactions).

Overall, controlling for variation in running speed slightly weakened the increase in theta frequency seen over days-of-experience within a given environment and slightly strengthened the theta frequency reduction on encountering the unexpected environments on change days 1*-3*. Stress has been also reported to affect theta frequency, but tends to increase it (Fontani, Farabollini, & Carli, 1984), consistent with the effects of anxiolytics in decreasing theta frequency (Gray & McNaughton, 2000), so that any novelty-induced stress could only have weakened the novelty-related decrease in frequency effects reported here.

Discussion

Our results suggest that environmental novelty is signaled by a reduced HF theta frequency (compared to that in a familiar environment), with unexpected change to a familiar environment within a common arena setting causing a greater reduction than first exposure to an entirely novel setting. As well as suggesting a new mechanism for signaling novelty, our results support the suggestion that the hippocampus performs a comparator function in detecting where experience (in this case, environmental layout) differs from expectation, rather than detecting absolute novelty per se (Sokolov , 1963; Vinogradova, 2001; Gray & McNaughton, 2000; Honey et al., 1998; Aggleton & Brown, 1999; Strange et al., 1999; Hasselmo et al., 1996; Lisman & Otmakhova, 2001; Kumaran & Maguire, 2006; Kohler et al., 2005). The specific mechanism found, theta frequency reduction, has significant implications for understanding the oscillatory coding found within the hippocampal system (O’Keefe & Recce, 1993; Lisman & Otmakhova, 2001; Hasselmo, 2006; Harris et al., 2002; Mehta, Lee, & Wilson, 2002; Huxter, Burgess, & O’Keefe, 2003; Skaggs, McNaughton, Wilson, & Barnes, 1996). In this context, we note that, although theta phase can vary with location across the HF, theta frequency is constant within HF (Buzsaki, 2002) and thus suitable for mediating a generic signal such as contextual novelty. Since gamma power is higher during theta-associated behaviours, relates to hippocampal memory function, is strongly modulated by theta phase in the HF and neocortex in rats and humans, and theta frequency and gamma frequency covary (Bragin et al., 1995; Chrobak & Buzsaki, 1998; Canolty et al., 2006; Jensen & Colgin, 2007; Montgomery & Buzsaki, 2007) our findings have implications for models of oscillatory encoding in memory in both the theta and gamma ranges (Lisman & Otmakhova, 2001; Mormann et al., 2005; Sederberg et al., 2003; Jacobs et al., 2006; Osipova et al., 2006; Rizzuto et al., 2006; Lisman & Idiart, 1995).

We can only speculate as to the mechanism for the theta frequency reduction, however there appear to be two components to HF theta: the movement-related cholinergically independent theta with frequency 8-9Hz, and a lower frequency atropine-sensitive (i.e. cholinergically mediated) frequency of around 6Hz (Klink & Alonso, 1997; Kramis et al., 1975). The medial septum sets the pace of HF theta and provides both GABAergic and cholinergic inputs, see (Buzsaki, 2002; O’Keefe, 2006) for reviews. Increase in cholinergic input to the hippocampus, as seen during exploration of a novel environment (Giovannini et al., 2001; Thiel, Huston, & Schwarting, 1998), results in a reduction of hippocampal theta frequency (Givens & Olton, 1995). Our results support the idea that the GABAergic input sets baseline theta frequency during motion, with increased cholinergic input mediating a reduction in overall frequency in response to novelty. This would be consistent with the rapid and slow synaptic actions of GABA and acetylcholine respectively, and with the proposed involvement of acetylcholine in signaling novelty (Hasselmo, 2006; Meeter et al., 2004; Carlton, 1968; Hasselmo, Schnell, & Barkai, 1995). This interpretation is less obviously consistent with a proposed role of acetylcholine in ‘expected uncertainty’, as compared with ‘unexpected uncertainty’ (Yu & Dayan, 2005), but our random foraging task precludes any direct correspondence to this proposal. The trigger for increased cholinergic innervation from the medial septum might arise from the HF itself, on the basis of the comparison of the stored representation of an environment with the altered input (Sokolov , 1963; Vinogradova, 2001; O’Keefe & Nadel, 1978; Lisman & Otmakhova, 2001; Gray & McNaughton, 2000; Hasselmo et al., 1996; Borisyuk et al., 2001; Meeter et al., 2004; Myers et al., 1996).

An electrophysiological signature of contextual novelty has been identified in the human hippocampus (e.g., the ’MTL-P300 Knight, 1996; Grunwald et al., 1998; Grunwald & Kurthen, 2006; Halgren et al., 1980; Rugg & Coles, 1995). The cause of these event-related potentials is the subject of much speculation: as well as synaptic/neuronal activity triggered by the novel event, further suggested contributions include non-time-locked ‘induced’ activity, event-triggered phase alignment of ongoing oscillations and increased power at specific frequencies (Makeig et al., 2002; Duzel, Neufang, & Heinze, 2005; Fell et al., 2004; Rizzuto et al., 2003; McCartney et al., 2004; Axmacher et al., 2006). Our results imply that a fourth mechanism may play a role: namely stimulus-induced changes in characteristic frequencies such as theta.

The proposed relationship between novelty and theta frequency has implications for, but is not necessarily incompatible with, current models in which theta provides separate phases for encoding and retrieval (Hasselmo, 2006; Meeter et al., 2004; Borisyuk et al., 2001; Hasselmo et al., 2002), interacts with gamma frequency oscillations to organize memory for sequences (Lisman & Otmakhova, 2001; Lisman & Idiart, 1995; Jensen & Colgin, 2007), or provides a clock signal against which information is encoded by firing phase in hippocampus (O’Keefe & Recce, 1993; Skaggs et al., 1996) or entorhinal cortex (Burgess et al., 2007). More specifically, our results support the oscillatory interference model (Burgess et al., 2007) of the firing of medial entorhinal grid cells (Hafting, Fyhn, Molden, Moser, & Moser, 2005), which predicts that a change in the frequency of movement-related theta underlies the increase in the spatial scale of the firing pattern of grid cells seen in novel environments (Fyhn, Hafting, Treves, Moser, & Moser, 2006). This in turn might contribute to changes in place cell firing when the rat experiences a novel environment (‘remapping’ (Bostock et al., 1991)), by causing a mismatch between the grid cells’ inputs to place cells and environmental sensory information from lateral entorhinal cortex (Burgess et al., 2007). This model requires further experimental investigation to determine its relationship to mechanisms supporting the effects of novelty, e.g., the potential roles acetylcholine and atropine-sensitive theta, but predicted the result presented here and suggests a new mechanism by which environmental novelty might trigger the formation of new hippocampal representations.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated a new potential mechanism for signaling of environmental novelty: a reduction in the theta frequency generated by hippocampal formation. Our results have important implications for the interpretation of event-related potentials, and support the idea that the hippocampal formation plays a greater role in ‘contextual novelty’ or ‘comparator’ processing than absolute novelty per se. In addition, they support the hypothesis of a cholinergically-mediated mechanism for novelty detection, and provide indirect support for the oscillatory interference model of grid cell firing.

Acknowledgements

Supported by the Wellcome Trust and MRC, U.K. The authors would like to thank C. Barry, C. Bird, P. Cairns, C. Doeller, C. Frost, J.A. King, K. Jeffery and A. McClelland for useful discussions. Work was conducted according to institutional and national ethical guidelines as outlined in the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act, 1986.

Reference List

- Aggleton JP, Brown MW. Episodic memory, amnesia, and the hippocampal-anterior thalamic axis. Behavioural Brain Sci. 1999;22:425–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axmacher N, Mormann F, Fernandez G, Elger CE, Fell J. Memory formation by neuronal synchronization. Brain Res.Rev. 2006;52:170–182. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borisyuk R, Denham M, Hoppensteadt F, Kazanovich Y, Vinogradova O. Oscillatory model of novelty detection. Network. 2001;12:1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostock E, Muller RU, Kubie JL. Experience-dependent modifications of hippocampal place cell firing. Hippocampus. 1991;1:193–205. doi: 10.1002/hipo.450010207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bragin A, Jando G, Nadasdy Z, Hetke J, Wise K, Buzsaki G. Gamma (40-100 Hz) oscillation in the hippocampus of the behaving rat. J.Neurosci. 1995;15:47–60. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-01-00047.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock TH, Buzsaki G, McClune MC. Coherence of compound field potentials reveals discontinuities in the CA1-subiculum of the hippocampus in freely-moving rats. Neuroscience. 1990;38:609–619. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90055-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess N, Barry C, O’Keefe J. An oscillatory interference model of grid cell firing. Hippocampus. 2007;17:801–812. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzsaki G. Theta oscillations in the hippocampus. Neuron. 2002;33:325–340. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00586-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacucci F, Lever C, Wills TJ, Burgess N, O’Keefe J. Theta-modulated place-by-direction cells in the hippocampal formation in the rat. J Neurosci. 2004;24:8265–8277. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2635-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canolty RT, Edwards E, Dalal SS, Soltani M, Nagarajan SS, Kirsch HE, et al. High gamma power is phase-locked to theta oscillations in human neocortex. Science. 2006;313:1626–1628. doi: 10.1126/science.1128115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlton PL. Brain acetylcholine and habituation. Prog.Brain Res. 1968;28:48–60. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)64542-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrobak JJ, Buzsaki G. Gamma oscillations in the entorhinal cortex of the freely behaving rat. J.Neurosci. 1998;18:388–398. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-01-00388.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen NJ, Eichenbaum H. Memory, amnesisa and the hippocampal system. Cambridge Massachusettes: MIT Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Duzel E, Neufang M, Heinze HJ. The oscillatory dynamics of recognition memory and its relationship to event-related responses. Cereb.Cortex. 2005;15:1992–2002. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrom AD, Caplan JB, Ho E, Shattuck K, Fried I, Kahana MJ. Human hippocampal theta activity during virtual navigation. Hippocampus. 2005;15:881–889. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fell J, Dietl T, Grunwald T, Kurthen M, Klaver P, Trautner P, et al. Neural bases of cognitive ERPs: more than phase reset. J Cogn Neurosci. 2004;16:1595–1604. doi: 10.1162/0898929042568514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontani G, Farabollini F, Carli G. Hippocampal electrical activity and behavior in the presence of novel environmental stimuli in rabbits. Behav Brain Res. 1984;13:231–240. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(84)90165-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried I, MacDonald KA, Wilson CL. Single neuron activity in human hippocampus and amygdala during recognition of faces and objects. Neuron. 1997;18:753–765. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80315-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyhn M, Hafting T, Treves A, Moser EI, Moser MB. Coherence in ensembles of entorhinal grid cells. Soc.Neurosci.Abstr. 2006 68.9/BB17. [Google Scholar]

- Fyhn M, Hafting T, Treves A, Moser MB, Moser EI. Hippocampal remapping and grid realignment in entorhinal cortex. Nature. 2007;446:190–194. doi: 10.1038/nature05601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyhn M, Molden S, Hollup S, Moser MB, Moser E. Hippocampal neurons responding to first-time dislocation of a target object. Neuron. 2002;35:555–566. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00784-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovannini MG, Rakovska A, Benton RS, Pazzagli M, Bianchi L, Pepeu G. Effects of novelty and habituation on acetylcholine, GABA, and glutamate release from the frontal cortex and hippocampus of freely moving rats. Neuroscience. 2001;106:43–53. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00266-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Givens B, Olton DS. Bidirectional modulation of scopolamine-induced working memory impairments by muscarinic activation of the medial septal area. Neurobiol.Learn.Mem. 1995;63:269–276. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1995.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA, McNaughton N. The neuropsychology of anxiety. 2nd ed Oxford: O.U.P.; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Grunwald T, Kurthen M. Novelty detection and encoding for declarative memory within the human hippocampus. Clin.EEG.Neurosci. 2006;37:309–314. doi: 10.1177/155005940603700408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunwald T, Lehnertz K, Heinze HJ, Helmstaedter C, Elger CE. Verbal novelty detection within the human hippocampus proper. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:3193–3197. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafting T, Fyhn M, Molden S, Moser MB, Moser EI. Microstructure of a spatial map in the entorhinal cortex. Nature. 2005;436:801–806. doi: 10.1038/nature03721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halgren E, Squires NK, Wilson CL, Rohrbaugh JW, Babb TL, Crandall PH. Endogenous potentials generated in the human hippocampal formation and amygdala by infrequent events. Science. 1980;210:803–805. doi: 10.1126/science.7434000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KD, Henze DA, Hirase H, Leinekugel X, Dragoi G, Czurko A, et al. Spike train dynamics predicts theta-related phase precession in hippocampal pyramidal cells. Nature. 2002;417:738–741. doi: 10.1038/nature00808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselmo ME. The role of acetylcholine in learning and memory. Curr Opin.Neurobiol. 2006;16:710–715. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselmo ME, Bodelon C, Wyble BP. A proposed function for hippocampal theta rhythm: separate phases of encoding and retrieval enhance reversal of prior learning. Neural Comput. 2002;14:793–817. doi: 10.1162/089976602317318965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselmo ME, Schnell E, Barkai E. Dynamics of learning and recall at excitatory recurrent synapses and cholinergic modulation in rat hippocampal region CA3. J.Neurosci. 1995;15:5249–5262. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-07-05249.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselmo ME, Wyble BP, Wallenstein GV. Encoding and retrieval of episodic memories: role of cholinergic and GABAergic modulation in the hippocampus. Hippocampus. 1996;6:693–708. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1996)6:6<693::AID-HIPO12>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honey RC, Watt A, Good M. Hippocampal lesions disrupt an associative mismatch process. J.Neurosci. 1998;18:2226–2230. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-06-02226.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxter J, Burgess N, O’Keefe J. Independent rate and temporal coding in hippocampal pyramidal cells. Nature. 2003;425:828–832. doi: 10.1038/nature02058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs J, Hwang G, Curran T, Kahana MJ. EEG oscillations and recognition memory: theta correlates of memory retrieval and decision making. Neuroimage. 2006;32:978–987. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen O, Colgin LL. Cross-frequency coupling between neuronal oscillations. Trends Cogn Sci. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klink R, Alonso A. Muscarinic modulation of the oscillatory and repetitive firing properties of entorhinal cortex layer II neurons. J.Neurophysiol. 1997;77:1813–1828. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.4.1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight R. Contribution of human hippocampal region to novelty detection. Nature. 1996;383:256–259. doi: 10.1038/383256a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler S, Danckert S, Gati JS, Menon RS. Novelty responses to relational and non-relational information in the hippocampus and the parahippocampal region: a comparison based on event-related fMRI. Hippocampus. 2005;15:763–774. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramis R, Vanderwolf CH, Bland BH. Two types of hippocampal rhythmical slow activity in both the rabbit and the rat: relations to behavior and effects of atropine, diethyl ether, urethane, and pentobarbital. Exp.Neurol. 1975;49:58–85. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(75)90195-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumaran D, Maguire EA. An unexpected sequence of events: mismatch detection in the human hippocampus. PLoS.Biol. 2006;4:e424. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenck-Santini PP, Rivard B, Muller RU, Poucet B. Study of CA1 place cell activity and exploratory behavior following spatial and nonspatial changes in the environment. Hippocampus. 2005;15:356–369. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leutgeb JK, Leutgeb S, Treves A, Meyer R, Barnes CA, McNaughton BL, et al. Progressive transformation of hippocampal neuronal representations in “morphed” environments. Neuron. 2005;48:345–358. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lever C, Wills T, Cacucci F, Burgess N, O’Keefe J. Long-term plasticity in hippocampal place-cell representation of environmental geometry. Nature. 2002;416:90–94. doi: 10.1038/416090a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisman JE, Idiart MA. Storage of 7 +/-2 short-term memories in oscillatory subcycles. Science. 1995;267:1512–1515. doi: 10.1126/science.7878473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisman JE, Otmakhova NA. Storage, recall, and novelty detection of sequences by the hippocampus: elaborating on the SOCRATIC model to account for normal and aberrant effects of dopamine. Hippocampus. 2001;11:551–568. doi: 10.1002/hipo.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makeig S, Westerfield M, Jung TP, Enghoff S, Townsend J, Courchesne E, et al. Dynamic brain sources of visual evoked responses. Science. 2002;295:690–694. doi: 10.1126/science.1066168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCartney H, Johnson AD, Weil ZM, Givens B. Theta reset produces optimal conditions for long-term potentiation. Hippocampus. 2004;14:684–687. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeter M, Murre JM, Talamini LM. Mode shifting between storage and recall based on novelty detection in oscillating hippocampal circuits. Hippocampus. 2004;14:722–741. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta MR, Lee AK, Wilson MA. Role of experience and oscillations in transforming a rate code into a temporal code. Nature. 2002;417:741–746. doi: 10.1038/nature00807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery SM, Buzsaki G. Gamma oscillations dynamically couple hippocampal CA3 and CA1 regions during memory task performance. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2007;104:14495–14500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701826104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mormann F, Fell J, Axmacher N, Weber B, Lehnertz K, Elger CE, et al. Phase/amplitude reset and theta-gamma interaction in the human medial temporal lobe during a continuous word recognition memory task. Hippocampus. 2005;15:890–900. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller R. A quarter of a century of place cells. Neuron. 1996;17:813–822. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80214-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers CE, Ermita BR, Harris K, Hasselmo M, Solomon P, Gluck MA. A computational model of cholinergic disruption of septohippocampal activity in classical eyeblink conditioning. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 1996;66:51–66. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1996.0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakazawa K, Quirk MC, Chitwood RA, Watanabe M, Yeckel MF, Sun LD, et al. Requirement for hippocampal CA3 NMDA receptors in associative memory recall. Science. 2002;297:211–218. doi: 10.1126/science.1071795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe J. Hippocampal neurophysiology in the behaving animal. In: Andersen P, Morris RGM, Amaral DG, Bliss TVP, O’Keefe J, editors. The Hippocampus Book. Oxford: Oxford Neuroscience; 2006. pp. 475–548. [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe J. Place units in the hippocampus of the freely moving rat. Exp.Neurol. 1976;51:78–109. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(76)90055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe J, Nadel L. The hippocampus as a cognitive map. Oxford University Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe J, Recce ML. Phase relationship between hippocampal place units and the EEG theta rhythm. Hippocampus. 1993;3:317–330. doi: 10.1002/hipo.450030307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osipova D, Takashima A, Oostenveld R, Fernandez G, Maris E, Jensen O. Theta and gamma oscillations predict encoding and retrieval of declarative memory. J.Neurosci. 2006;26:7523–7531. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1948-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganath C, Rainer G. Neural mechanisms for detecting and remembering novel events. Nat.Rev.Neurosci. 2003;4:193–202. doi: 10.1038/nrn1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzuto DS, Madsen JR, Bromfield EB, Schulze-Bonhage A, Kahana MJ. Human neocortical oscillations exhibit theta phase differences between encoding and retrieval. Neuroimage. 2006;31:1352–1358. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzuto DS, Madsen JR, Bromfield EB, Schulze-Bonhage A, Seelig D, Aschenbrenner-Scheibe R, et al. Reset of human neocortical oscillations during a working memory task. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:7931–7936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0732061100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rugg MD, Coles MG. Electrophysiology of Mind: Event-Related Potentials and Cognition. Oxford: O.U.P.; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Rutishauser U, Mamelak AN, Schuman EM. Single-trial learning of novel stimuli by individual neurons of the human hippocampus-amygdala complex. Neuron. 2006;49:805–813. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sederberg PB, Kahana MJ, Howard MW, Donner EJ, Madsen JR. Theta and gamma oscillations during encoding predict subsequent recall. J Neurosci. 2003;23:10809–10814. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-34-10809.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skaggs WE, McNaughton BL, Wilson MA, Barnes CA. Theta phase precession in hippocampal neuronal populations and the compression of temporal sequences. Hippocampus. 1996;6:149–172. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1996)6:2<149::AID-HIPO6>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokolov EN. Higher nervous functions; the orienting reflex. Annu.Rev.Physiol. 1963;25:545–580. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.25.030163.002553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squire LR, Zola-Morgan S. The medial temporal lobe memory system. Science. 1991;253:1380–1386. doi: 10.1126/science.1896849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strange BA, Fletcher PC, Henson RN, Friston KJ, Dolan RJ. Segregating the functions of human hippocampus. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 1999;96:4034–4039. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.4034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiel CM, Huston JP, Schwarting RK. Hippocampal acetylcholine and habituation learning. Neuroscience. 1998;85:1253–1262. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00030-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderwolf CH. Hippocampal electrical activity and voluntary movement in the rat. Electroencephalogr.Clin.Neurophysiol. 1969;26:407–418. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(69)90092-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinogradova OS. Hippocampus as comparator: role of the two input and two output systems of the hippocampus in selection and registration of information. Hippocampus. 2001;11:578–598. doi: 10.1002/hipo.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whishaw IQ, Vanderwolf CH. Hippocampal EEG and behavior: effects of variation in body temperature and relation of EEG to vibrissae movement, swimming and shivering. Physiol Behav. 1971;6:391–397. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(71)90172-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills T, Lever C, Cacucci F, Burgess N, O’Keefe J. Attractor Dynamics in the Hippocampal Representation of the Local Environment. Science. 2005;308:873–876. doi: 10.1126/science.1108905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu AJ, Dayan P. Uncertainty, neuromodulation, and attention. Neuron. 2005;46:681–692. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]