Abstract

Psychostimulant abuse is a serious social and health problem, for which no effective treatments currently exist. A number of review articles have described predominantly ‘clinic’-based pharmacotherapies for the treatment of psychostimulant addiction, but none have yet been shown to be definitively effective for use in humans. In the present article, we review various ‘hypothesis’- or ‘mechanism’-based pharmacological agents that have been studied at the preclinical level and evaluate their potential use in the treatment of psychostimulant addiction in humans. These compounds target brain neurotransmitter or neuromodulator systems, including dopamine (DA), γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), endocannabinoid, glutamate, opioid and serotonin, which have been shown to be critically involved in drug reward and addiction. For drugs in each category, we first briefly review the role of each neurotransmitter system in psychostimulant actions, and then discuss the mechanistic rationale for each drug’s potential anti-addiction efficacy, major findings with each drug in animal models of psychostimulant addiction, abuse liability and potential problems, and future research directions. We conclude that hypothesis-based medication development strategies could significantly promote medication discovery for the effective treatment of psychostimulant addiction.

Keywords: Psychostimulant, addiction, reward, reinstatement, dopamine, glutamate, GABA, endocannabinoids

1. INTRODUCTION

Psychostimulant abuse is a major medical and social problem. Cocaine, amphetamine, methamphetamine and N-methyl-3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, ecstasy) are the most commonly abused psychostimulants in humans. The acute rewarding effects produced by psychostimulants and craving and relapse after abstinence are the core features of addiction to these drugs [1, 2]. Currently, there are no effective medications available for the treatment of psychostimulant addiction [3–5].

The lack of effective medications has spurred increased research attention. Recently, several review articles have described the progress of a number of pharmacological agents that are believed to be possibly effective in treatment of psychostimulant addiction [3–10]. However, most of these have focused on preliminary clinical findings (or ‘clinical’-based medication discovery), and none of the potentially effective agents described has yet been clearly shown to be effective in humans [4–9]. We have previously argued that knowledge of the underlying brain mechanisms of addiction, garnered from diligent and astute use of preclinical animal models relevant to addiction, provides an alternative – and arguably more rational – approach to the development of effective anti-addiction treatment medications [11, 12]. On this rationale, we focus in the present review on ‘mechanism’-based medication development strategies and we evaluate the pharmacological efficacy in animal models of drug addiction of various novel pharmacological agents possibly effective for the treatment of psychostimulant addiction. Animal models of disease are, by definition, approximations of the corresponding human clinical conditions. Since no single model can fully emulate all aspects of human drug abuse, multiple animal models or paradigms have been developed to reflect different aspects of the human addictive process. Among them, drug self-administration, brain stimulation reward (BSR), conditioned place preference (CPP) and drug discrimination are the most commonly used animal paradigms for studying the acute rewarding effects of drugs of abuse. Reinstatement models of drug-seeking behavior -triggered by the addictive drug itself, drug-paired environmental cues, or stress - are the most commonly used animal paradigms to emulate drug craving and relapse to drug use in humans. Detailed descriptions of each of these animal paradigms have been reported elsewhere [1, 3, 11, 12].

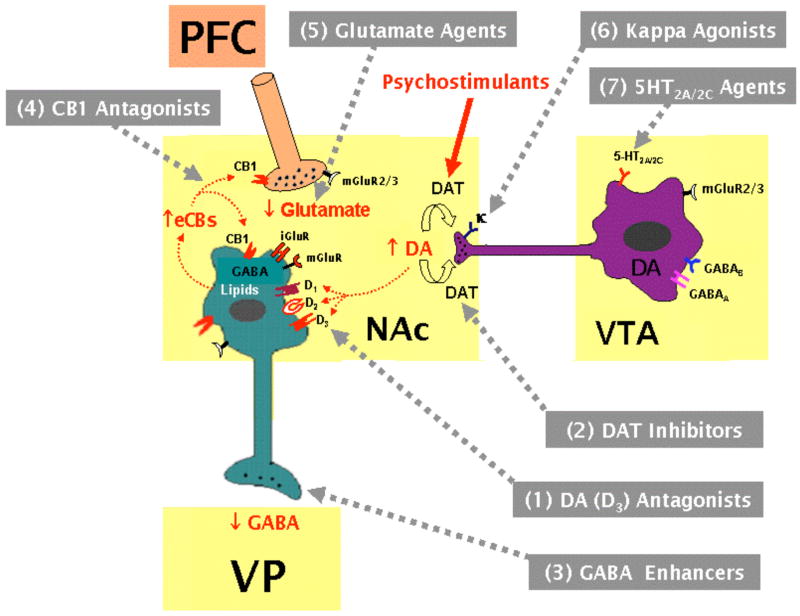

Extensive studies during several decades indicate that the neurotransmitter or neuromodulator systems most critically involved in drug reward and addiction are those involving dopamine (DA), γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), endocannabinoids, glutamate, endogenous opioids, and serotonin [13–19]. Therefore, in the present review article, we first briefly review the functional role of each neurotransmitter in psychostimulant reward and relapse, and then summarize major findings in animal models of psychostimulant addiction produced by 27 pharmacological agents that target these neurotransmitter systems. We then discuss the potential use of these compounds in the clinical treatment of psychostimulant addiction. Recent studies also suggest that acetylcholine, several neuropeptides, and other neuro-signaling systems are involved in psychostimulant addiction [20, 21]. We do not review these systems in the present article because many findings are controversial or inconclusive, or reported elsewhere.

2. DOPAMINE-BASED MEDICATION DISCOVERY – ANTAGONIST STRATEGIES

Mesolimbic DA hypothesis of drug reward

It is well documented that the mesolimbic DA system is critically involved in drug reward and addiction [13–14, 17]. This system originates from the DA neurons in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) in the midbrain and predominantly projects to the NAc, prefrontal cortex (PFC) and amygdala in the forebrain. A great deal of evidence supports the importance of this DA system in drug addiction. First, almost all addictive drugs, including cocaine, amphetamine, opiates, nicotine, marijuana or ethanol, increase extracellular DA in the NAc [13–14, 17, 22]. Second, almost all addictive drugs are self-administered by animals either intravenously or locally into brain DA loci, an effect that can be blocked by either selective lesions of DA terminals or by pharmacological blockade of DA receptors [23, 24]. Third, electrical stimulation of brain DA loci maintains BSR, which is enhanced by drugs of abuse and attenuated by DA receptor antagonists [25, 26]. Cocaine-induced increases in extracellular DA are mediated by blockade of DA reuptake, while amphetamine- or methamphetamine-induced increases in extracellular DA are mediated predominantly by reversal of DA transporters [14, 17, 27]. These increases in synaptic DA levels in forebrain reward loci — especially in the NAc — are thought to underlie the euphoria associated with psychostimulant use [13–14, 17, 28]. Based on these findings, much development of new medications for treatment of psychostimulant addiction has focused on manipulation of DA transmission in the reward circuitry of the brain. Two major pharmacological strategies for manipulating brain DA transmission have emerged as the basis of anti-psychostimulant medication development: one being to modulate brain DA receptors, and the other being to modulate DA transporters. The former strategy has – to date – primarily utilized DA receptor antagonists, while the latter strategy has – to date – primarily utilized indirect DA receptor agonists that can be viewed as pharmacologically substituting for the addictive psychostimulants in a manner analogous to methadone substitution for heroin. Recently, extensive studies have demonstrated that the DA agents summarized in Table 1 appear to be promising for the treatment of psychostimulant addiction.

Table 1.

Pharmacological Actions of DA Receptor Antagonists in Animal Models or Paradigms of Psychostimulant Addiction

| l-THP | BP-897 | SB-277011A | NGB2904 | S33138 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacological Actions | DA (D1, D2, and maybe D3) antagonist | D3 partial agonist | D3 antagonist | D3 antagonist | D3-preferring antagonist |

| Self-Administration (SA) | ↓ Cocaine SA (FR, PR) | ↓ Cocaine SA (PR, 2nd-order, not FR) | ↓ Cocaine SA (PR, 2nd-order, not FR)

↓ METH SA (PR, not FR) |

↓ Cocaine SA (PR, not FR) | ↓ Cocaine SA (PR, not FR) |

| Reinstatement of Drug-Seeking (Relapse) | ↓ Relapse by cocaine | ↓ Relapse by cocaine, by cues | ↓ Relapse by cocaine, cues or stress | ↓ Relapse by cocaine or cues | ↓ Relapse by cocaine |

| Conditioned Place Preference (CPP) | ↓ CPP by cocaine or METH | ↓ CPP by cocaine | ↓ CPP by cocaine | ||

| Enhanced Brain-Stimulation Reward (eBSR) | ↓ eBSR by cocaine | ↓ eBSR by cocaine or METH | ↓ eBSR by cocaine or METH | ↓ eBSR by cocaine or METH | ↓ eBSR by cocaine or METH |

| Psychostimulant-like Discriminative Stimulus Effects (DS) | ↓ DS by cocaine or Amphetamine | ||||

| Behavioral Sensitization (BS) | ↓ BS by cocaine Cue | ||||

| Abuse Liability | No SA by itself | No SA by itself | No SA by itself | No SA by itself | |

| Natural Reward | ↓ Sucrose-taking

↓ Food-taking |

No effect on sucrose-seeking | No effect on food-taking | No effect on sucrose-seeking | ↓ Sucrose-taking |

| Clinical Use or Trials | For pain and insomnia for 40 years | Phase II | No | No | No |

l-THP: Levo-tetrahydropalmantine

FR: Pixed-ratio reinforcement

PR: Progressive-ratio reinforcement

2nd-order: Self-administration under second-order reinforcement

METH: Methamphetamine.

2.1. Levo-tetrahydropalmatine (l-THP)

It is well documented that both D1 and D2 receptors are critically involved in drug reward and addiction [3, 29, 30]. However, clinical trials with D1- or D2-like receptor antagonists have failed because of lack of therapeutic effect with D1-like antagonists or severe side-effects with D2-like antagonists - such as dysphoria, supression of natural reward or abnormal movements [3, 29–32]. In contrast to D1- or D2-like receptor antagonists, l-THP is a non-selective D1 and D2 (and possibly D3) receptor antagonist [33–36], purified from the Chinese herb Stephanie [33]. l-THP has been used in China as a traditional sedative-analgesic agent for more than 40 years for the treatment of chronic pain and anxious insomnia. Recent studies have shown that l-THP significantly inhibits: 1) cocaine- or methamphetamine-induced CPP [37, 38]; 2) cocaine self-administration under fixed-ratio (FR) reinforcement and progressive-ratio (PR) reinforcement schedules [36, 39]; 3) cocaine-enhanced electrical BSR [39]; and 4) cocaine-triggered reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior in rats [36]. Such data support the potential use of l-THP in the treatment of psychostimulant dependence. The attenuation of cocaine’s actions in the above cited animal models of drug addiction are unlikely due to l-THP-induced sedation or locomotor inhibition, because the effective doses for attenuation of cocaine’s actions are much lower (3–10 fold) than those for inhibition of locomotion or sucrose self-administration [39]. In addition, l-THP also inhibits opioid tolerance and withdrawal syndromes in rats [40], as well as locomotor sensitization to oxycodone in mice [41], suggesting an anti-addictive utility broader than just for psychostimulants. A recent clinical trial demonstrates that l-THP significantly attenuates drug craving and relapse in heroin addicts [42].

In vivo microdialysis demonstrates that l-THP modestly elevates extracellular NAc DA by itself, and also dose-dependently potentiates cocaine-augmented DA [39], suggesting an action on presynaptic DA D2/3 receptors. However, such presynaptic action is unlikely to mediate the antagonism by l-THP of cocaine’s actions, suggesting a post-synaptic mechanism underlying the pharmacotherapeutic effects of l-THP. Although l-THP modestly elevates NAc DA, it can not maintain intravenous self-administration behavior in rats previously self-administered cocaine (Xi et al., unpublished data), suggesting that l-THP has no abuse potential by itself. Given that chronic cocaine appears to produce a reduction in basal mesolimbic DA transmision in both humans and experimental animals after withdrawal or abstinence [23, 43–46], the l-THP-induced modest augmentation of extracellular DA may also contribute to its therapeutic anti-cocaine actions by correcting the hypofunctional DA state. Since l-THP is a natural and cost-effective substance purified from Chinese herbs, and is well-tolerated in humans with few side-effects [33], the above pre-clinical findings support the potential use of l-THP for the treatment of cocaine or other pyschostimulant addiction.

2.2. BP-897

Recent research interest in DA D3 receptor-selective compounds in medication discovery for the treatment of psychostimulant addiction is derived from the unique anatomical distribution of D3 receptors in the brain. D3 receptors are preferentially localized in the mesolimbic DA system with the highest receptor densities in the NAc, islands of Calleja and olfactory tubercle [47, 48]. This restricted neuroanatomic localization suggests an important role for D3 receptors in drug reward and addiction [49, 50]. In addition, D3 receptors have the highest affinity for endogenous DA of all known receptors [49, 51], suggesting a crucial role for D3 receptors in the normal functioning of the mesolimbic reward system. Based on these and other considerations, it was hypothesized that pharmacological agents that block brain D3 receptors might be effective in the treatment of psychostimulant dependence [49, 50, 52].

BP-897 [1-(4-(2-naphthoylamino)butyl)-4-(2-methoxyphenyl)-1A-piperazine] is the first developed D3-selective pharmacological agent. It has been claimed to act as a D3 partial agonist [53] or antagonist [54, 55]. It has modest (60–70 fold) selectivity for human D3 versus D2 receptors, and similar (60–70 fold) selectivity over other receptors such as α1-, α2-adrenergic, and 5-HT1A receptors [53]. Several studies have assessed the efficacy of BP-897 in animal models of drug addiction [56, 57]. Briefly, it has been reported that BP-897 produces a significant dose-dependent reduction in: 1) cocaine self-administration under second-order reinforcement [53], but not under FR reinforcement [58]; 2) cocaine- or cocaine-cue-triggered reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior [59–61]; 3) cocaine-induced CPP [62–64]; 4) cocaine’s or amphetamine’s discriminative stimulus properties [65]; and 5) cocaine cue-induced increases in locomotion and behavioral sensitization [66]. These data support the potential use of BP-897 in the treatment of cocaine or other psychostimulant addiction [56, 57, 67, 68].

However, enthusiasm for BP-897 has waned due to recent findings that BP-897 also displays full antagonist properties at both DA D2 and D3 receptors [54, 55, 57]. Given that D2 receptor antagonism usually produces severe unwanted side-effects, such as dysphoria, inhibition of natural reward, and abnormal extrapyramidal movements [3, 29, 30], BP-897’s D2 antagonist properties raise the possibility of unwanted side-effects at the human level. BP-897 has recently entered Phase II clinical studies, but detailed pharmacokinetic and toxicological data have not yet been reported.

2.3. SB-277011A

SB-277011A [trans-N-[4-[2-(6-cyano-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinolin-2-yl)ethyl]cyclohexyl]-4-quinolinecarboxamide] is the most well characterized DA D3 receptor in antagonist to date. SB-277011A has high affinity for the human cloned DA D3 receptor, and the ratio of in vitro D3/D2 affinity of SB-277011A for human and rat is 120 and 80, respectively [69]. SB-277011A has a 100-fold selectivity or better over 180 other receptors, enzymes and ion channels [69]. Recently, we and others have assessed the pharmacological efficacy of SB-277011A in animal models of drug addiction. We found that SB-277011A attenuates: 1) cocaine- or methamphetamine-enhanced BSR [70, 71]; 2) cocaine-induced CPP [70]; 3) cocaine or methamphetamine self-administration under PR or high FR (FR10) reinforcement schedules [72, 73]; 4) cocaine-seeking behavior under second-order reinforcement conditions [74]; 5) cocaine-, cocaine cue- or stress-triggered relapse to cocaine-seeking behavior [59–60, 70, 75]; and 6) incubation of cocaine craving in rats [76]. These data suggest that SB-277011A significantly inhibits the acute rewarding effects of psychostimulants, incubation of cocaine craving, and reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior [57]. However, further development of SB-277011A has been halted by Glaxo-SmithKline Pharmaceuticals, due to unexpectedly poor bioavailability (~2%) and a very short half-life (<20 min) in primates [77, 78]. Therefore, development of other D3-selective antagonists with higher bioavailability and more promising pharmacotherapeutic profiles is required [79].

2.4. NGB 2904

NGB 2904 [N-(4-[4-{2,3-dichlorophenyl}-1-piperazinyl]butyl)-2-fluorenylcarboxamide] is another highly selective D3 receptor antagonist which demonstrates high binding affinities at primate and rat D3 receptors [79–81]. NGB 2904 has been reported to have >150-fold selectivity for primate D3 over D2 receptors, and >800-fold selectivity for rat D3 versus D2 receptors [79, 80]. In addition, it was found to have >5000-fold selectivity over D1, D4, and D5 receptors, 200- to 600-fold selectivity over α1, 5HT2 receptors, and >1000-fold selectivity versus other CNS targets in a 60-receptor Panlabs screen [80]. These in vitro profiles of NGB 2904 suggest it to be a promising D3 antagonist.

Based on this, we recently examined the pharmacological efficacy of NGB 2904 in animal models of psychostimulant addiction. We found that systemic administration of NGB 2904 inhibits: 1) intravenous cocaine self-administration maintained under PR reinforcement [82]; 2) cocaine- or cocaine cue-triggered reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior [60, 82]; and 3) cocaine- or methamphetamine-enhanced BSR [71, 82]. In addition, NGB 2904 inhibits nicotine- and heroin-enhanced BSR [83]. Further, NGB 2904 neither produces a dysphorigenic shift in BSR functions nor substitutes for cocaine in maintenance of self-administration behavior, suggesting that NGB 2904 itself has no addictive liability [83].

The effectiveness of NGB 2904 on PR cocaine self-administration and reinstatement of drug-seeking triggered by cocaine or cocaine-associated cues suggests a clinical therapeutic potential, particularly for relapse to drug-seeking behavior. NGB 2904 is currently not under clinical trial and detailed data regarding bioavailability and pharmacokinetic properties must still be gathered.

2.5. S33138

As described above, the selective D3 receptor antagonists SB-277011A and NGB 2904 are ineffective against intravenous cocaine and methamphetamine (and also nicotine or alcohol) self-administration under low fixed-ratio (FR1, FR2) reinforcement conditions. In addition, NGB 2904’s antagonism of cocaine- and methamphetamine-enhanced BSR displays an obvious “dose-window effect”. That is, only lower doses of NGB 2904 were effective in attenuating cocaine- or methamphetamine-enhanced BSR, and the anti-reward effects could be overcome by increasing the doses of cocaine or methamphetamine [71, 83]. These data suggest that selective D3 receptor antagonists may have limited potential against the direct rewarding effects produced by psychostimulants. Consequently, it was proposed that preferential D3 versus D2 receptor antagonists may be an effective strategy for treating psychostimulant addiction [39, 83–84], based upon the finding that blockade of both D3 and D2 receptors produces additive or synergistic effects in antagonizing drug reward, but produced fewer unwanted side-effects than selective D2 antagonists due to opposite locomotor effects produced by blockade of D3 (facilitation) versus D2 (suppression) receptors [84, 85].

S33138 (N-[4-[2-[(3aS,9bR)-8-cyano-1,3a,4,9b-tetrahydro [1]benzopyrano[3,4-c]pyrrol-2(3H)-yl)-ethyl]phenyl acetamide) is such a preferential D3 versus D2 receptor antagonist [86], displaying 25-fold selectivity for human (h) D3 over hD2 receptors (pKi, 8.7 vs. 7.1 and 7.3). Recently, we carried out a series of experiments to evaluate the efficacy of S33138 in animal models relating to cocaine addiction [87]. We found that systemic administration of S33138 dose-dependently attenuated cocaine-enhanced BSR, but at the highest dose S33138 produced a significant aversive-like shift in BSR reward functions. S33138 produced biphasic effects on cocaine self-administration, i.e., a moderate dose increased, while a high dose inhibited, cocaine self-administration under FR2 reinforcement. We suggest that the increase in cocaine self-administration produced by the moderate dose of S33138 could be a compensatory response to a partial reduction in cocaine reward. In addition, S33138 also dose-dependently inhibited oral sucrose self-administration at high doses. In the reinstatement model of relapse to drug-seeking behavior, S33138 dose-dependently inhibited cocaine-triggered reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior. This reduction in reward-taking/seeking behaviors is unlikely due to impaired locomotor performance, as S33138 decreased neither Ymax levels in the BSR paradigm nor locomotor activity. Finally, S33138, at doses of 0.04–0.36 mg/kg/infusion, is clained to not be self-administered intravenously in rhesus monkeys (France et al., unpublished data). These findings suggest that the preferential D3 versus D2 receptor antagonist S33138 may be useful for the treatment of cocaine addiction, and may even show advantages relative to selective D2 antagonists, although the aversive-like BSR effects and inhibition of natural reward at high doses is a caution. Currently, S33138 is under clinical trial as an anti-psychotic agent [84, 88].

3. DOPAMINE-BASED MEDICATION DISCOVERY – AGONIST SUBSTITUTION STRATEGIES

Agonist Substitution Hypothesis

Agonist substitution as a pharmacotherapy for psychostimulant addiction is based on, first, the success of methadone in the treatment of opiate dependence and the nicotine patch for smoking cessation; second, the finding that the speed with which addictive drugs enter the brain and elevate NAc DA is positively correlated with addictive potential [89, 90], with slow-onset long-acting compounds having lower addictive potential; third, the hypothesis that a compound with low addictive potential may substitute for one with high addictive potential, thereby decreasing the use of the highly addictive drug; and finally, the hypothesis that long-term increases in NAc DA may ameliorate the hypodopaminergic dysfunction believed to exist in human cocaine addicts, thereby minimizing drug craving and relapse [23, 43, 45, 46]. To achieve such DA agonist effects, medication development for anti-addiction purposes has concentrated on the development of DA reuptake or DA transporter (DAT) inhibitors rather than direct DA receptor agonists. Indeed, this strategy has been at the forefront of medication development for the treatment of cocaine addiction for more than a full decade [11, 91]. To date, a wide variety of structural classes have served as chemical templates for the development of slow-onset long-acting DAT inhibitors, including benztropines, mazindol, substituted piperazines, tropanes, indanamines and trans-aminotetralins (Table 2).

Table 2.

Pharmacological Actions of DA or Monoamine Transporter Inhibitors in Animal Models or Paradigms of Psychostimulant Addiction

| GBR12909 | RTI-336 | CTDP30,640 | CTDP31,345 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacological Actions | DA transporter inhibitor | DA transporter inhibitor | Monoamine transporter inhibitor | Monoamine transporter inhibitor |

| Self-Administration (SA) | ↓ Cocaine SA (FR, PR) | ↓ Cocaine SA (FR, 2nd-order) | ↓ Cocaine SA (FR) | ↓ Cocaine SA (FR) |

| Reinstatement of Drug-Seeking (Relapse) | ↓ Relapse by cocaine or cues | No effect on relapse by cocaine | ||

| Enhanced Brain-Stimulation Reward (eBSR) | ↓ eBSR by cocaine | ↑ eBSR by cocaine | ↑ eBSR by cocaine | |

| Psychostimulant-like Discriminative Stimulus Effects (DS) | ↑ DS by cocaine, by METH | |||

| Abuse Liability | SA by itself; Sensitization by itself | SA by itself; DS effect by itself | Sensitization by itself; DS effect by itself | SA by itself |

| Natural Reward | No effect on food-taking | ↓ Food-taking | ↓ Sucrose-taking | |

| Clinical Trials | Phase I/IIa | No | No | No |

3.1. GBR-12909 (Vanoxerine)

GBR-12909, a phenyl-substituted piperazine derivative, is a relatively slow-onset long-acting DAT inhibitor [92]. To date, it is the most extensively studied DAT inhibitor proposed to be beneficial in the treatment of cocaine addiction [93–96]. GBR-12909 binds to the DAT site with high affinity, and selectively inhibits DA re-uptake [97]. GBR-12909 can also compete with psychostimulants at the DAT site, thus blocking cocaine- or amphetamine-induced increases in NAc extracellular DA [98, 99]. Compared with the same doses of cocaine, GBR-12909-induced increases in striatal DA and locomotion are relatively slow-onset (<10 min vs. 10–20 min) and long-lasting (1 hr vs. 3–4 hr) [99, 100]. Pretreatment with GBR-12909 significantly inhibits cocaine self-administration in rats and nonhuman primates at doses that have little or no effect on food self-administration [101–104]. Repeated treatment with low doses of GBR-12909 also sustains the selective suppression of cocaine self-administration versus food self-administration [105]. Further, a single injection of a decanoate ester slow-release formulation of GBR-12909 produced a prolonged (up to one month) suppression of cocaine self-administration in nonhuman primates [92, 106]. These findings support GBR-12909 as a potential candidate for the treatment of cocaine addiction [96]. However, there are significant cautions associated with it. GBR-12909 itself produces cocaine-like augmentment of BSR [107] and cocaine-like discriminative stimulus effects [108]. It is also self-administered and triggers reinstatement of extinguished drug-seeking behavior in both rats and primates [109, 110]. These data suggest that GBR-12909 itself may have abuse potential. Finally, GBR-12909 produced rate-dependent cardiac QTc interval prolongation in five out of five subjects studied in Phase I human trials, prompting discontinuation of the trials [112].

3.2. RTI-336

RTI-336 [3beta-(4-chlorophenyl)-2beta-[3-(4′-methylphenyl)isoxazol-5-yl]tropane] is a novel slow-onset (30 min) long-acting (4 hrs) DAT inhibitor [90, 111]. It has >1000- and >400-fold selectivity for the DAT relative to the serotonin transporter (SERT) and norepinepherine transporter (NET), respectively [113]. Pretreatment with RTI-336 produced dose-dependent reduction in cocaine self-administration in both rats and nonhuman primates [114, 115]. The ED50 dose of RTI-336 for reducing cocaine self-administration resulted in approximately 90% DAT occupancy, suggesting that high levels of DAT occupancy by RTI-336 are required to reduce cocaine self-administration. However, co-administration of the ED50 dose of RTI-336 with the SERT inhibitor fluoxetine or citalopram produced robust reductions in cocaine self-administration in nonhuman primates [115], suggesting that blockade of both DAT and SERT may be more effective in attenuating cocaine’s reinforcement than selective blockade of DAT alone [116]. However, RTI-336, at the doses that effectively suppressed cocaine self-administration, also inhibited food-taking behavior under multiple second-order reinforcement schedules [115]. This is different from the relative selectivity of GBR-12909 in suppressing cocaine self-administration over food-taking behavior, as noted above. As with many other DAT inhibitors, RTI-336 itself reliably maintained self-administration behavior in all non-human primates tested [115], suggesting abuse liability by itself. In addition, RTI-336 itself also produced locomotor stimulating and cocaine-like drug-discrimination effects in mice and rats. However, when compared with cocaine, RTI-336 maintained lower rates of self-administration, produced weaker locomotion and cocaine-like drug discriminative stimulus effects across a broad range of doses, and showed very low locomotor sensitization [113, 117]. These data suggest that RTI-336 may have lower abuse potential than cocaine. So far, there are no human trials with RTI-336 reported.

3.3. CTDP30,640

CTDP30,640 is an indanamine analog with slow-onset and long-acting monoamine re-uptake inhibitor properties [118, 119]. The “CTDP” terminology derives from the “Cocaine Treatment Discovery Program” of the Extramural Program of the U.S. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Our interest in such a non-selective monoamine transporter inhibitor as a potential anti-cocaine medication originally stemmed from the fact that cocaine is also a non-selective monoamine transporter inhibitor. Thus, a monoamine transporter inhibitor with a slow-onset and long-acting profile might constitute a therapeutically useful substitute for cocaine. This possiblity is supported by a recent finding that combined DAT and SERT inhibition appears more effective in suppressing cocaine self-administration than a selective DAT inhibitor (RTI-336) alone, as mentioned above.

CTDP30,640 is a prodrug, which is metabolized to active metabolites by rate-limited N-demethylation to achieve the desired slow-onset long-lasting pharmacological profile. CTDP30,640 itself has little or no activity [118]. We have evaluated the efficacy of CTDP30,640 in preclinical animal paradigms of drug addiction. We found that: 1) CTDP30,640 produced a cocaine like enhancement of locomotor activity, but with a slow-onset (<10 min vs. 20 min) and striking long duration (2h vs 8h) compared with cocaine [118]; 2) CTDP30,640 produced cocaine-like drug-discrimination effects in rats [118]; 3) CTDP30640 produced a cocaine-like enhancement of BSR, but with a marked slow onset and prolonged duration (up to 25–48 hrs after 3–5 mg/kg) relative to cocaine [119]; 4) CTDP30,640 dose-dependently lowered cocaine self-administration, an effect that lasted for up to 28, 50, and 90 hrs after 2.5, 5.0, 10 mg/kg, respectively [119]; and finally, 5) in vivo brain microdialysis demonstrated that CTDP30,640 produced a marked cocaine-like enhancement of NAc DA with a very pronounced slow onset and long duration profile relative to cocaine [119]. These findings suggest that CTDP30,640 has cocaine-like rewarding, psychomotor stimulating and neurochemical properties with slow onset and extralong duration. The prolonged suppression of cocaine self-administration after a single dose of CTDP30,640 suggests the potential use of CTDP30,640 in the treatment of cocaine addiction. However, its strong psychomotor stimulant and stereotypy-inducing effects decrease enthusiasm for its further development [118].

3.4. CTDP31,345

Based on our work with CTDP30,640, we designed, synthesized and tested additional slow-onset long-acting monoamine transporter inhibitors as candidate compounds for the treatment of psychostimulant addiction. CTDP31,345 is a trans-aminotetralin derivative [118, 120]. Like CTDP 30,640, CTDP31,345 is also a prodrug, which is metabolized (N-demethylated) to CTDP31,346, a slow-onset long-acting non-selective monoamine transporter inhibitor. In vitro transporter binding assays demonstrate similar binding affinities of CTDP31,345 to cloned human DAT (Ki = 18 ± 5 nM) and SERT (Ki = 23 ± 7 nM), but a lower affinity to cloned human NET (Ki = 81 ± 10 mM). Functional reuptake assays with cell lines expressing each transporter revealed the IC50 of CTDP31,345 for inhibition of DA, serotonin (5-HT) and NE reuptake to be 330 ± 120, 3.6 ± 0.2 and 120 ± 60 nM, respectively (Froimowitz, unpublished data).

To determine whether CTDP31,345 is superior to CTDP30,640, Froimowitz et al. observed the effects of CTDP31,345 on locomotion and stereotypic behaviors in rats. They found that the locomotor stimulation effects of CTDP31,345 (3–56 mg/kg i.p.) appeared to be mild and not dose-dependent. CTDP31,345, at 10 mg/kg, produced the most robust increase among all the doses (3–56 mg/kg i.p.) tested, with peak effects occurring at 40 min and lasting for about 8 hr. At higher doses, CTDP31,345 lost locomotor stimulating effects in mice. In contrast to CTDP30,640, CTDP31,345 failed to produce stereotypic behaviors in the majority (~80%) of mice tested (Froimowitz and Forster, unpublished data). These data suggest that CTDP31,345 appears superior to CTDP30,640, at least with respect to possible motoric side effects.

Therefore, we went on to assess the actions of CTDP31,345 in animal models of drug addiction. We found that: 1) CTDP31,345 itself has cocaine-like properties in rats. Systemic administration of CTDP31,345 produced slow-onset (20–50 min) and long-lasting (at least 5–7 hrs) increases in locomotion and NAc extracellular DA, and a sustained (>24 hrs) enhancement of BSR in rats [121, 122]; 2) pretreatment with CTDP31,345 dose-dependently inhibited cocaine self-administration in rats, an effect that lasted for at least 24 hrs after a single injection of 20 mg/kg of CTDP31,345; 3) this reduction in cocaine self-administration appeared to be due to CTDP31,345’s substitution effects, because pretreatment with CTDP31,345 produced an enhancement of cocaine’s effects on locomotion, electrical BSR and NAc DA; 4) such enhancing effects of CTDP31,345 on cocaine’s actions are strikingly different from those of methadone on heroin’s actions, in which methadone pretreatment produces a dose-dependent reduction in heroin self-administration, heroin-enhanced BSR and heroin-enhanced NAc DA; and finally 5) CTDP31,345 itself also maintained self-administration at lower rates than cocaine when tested at comparable doses in rats [121, 122].

The potential use of CTDP31,345 in the treatment of cocaine addiction remains to be determined. Although its cocaine-like rewarding effects and potential abuse liability may limit its use, the long-term inhibition of cocaine self-administration after a single dose of CTDP31,345 administration does support its potential utility. In addition, CTDP31,345-induced long-term increases in NAc DA may also be helpful in relieving drug craving and relapse to drug use by restoring reduced synaptic DA function in brain reward circuits [43, 45]. Clearly, more studies are required to determine whether CTDP31,345 or other slow-onset long-acting monoamine transporter inhibitors with different chemical structures will have similar or different pharmacological profiles in animal paradigms of drug addiction, as compared to methadone, a ‘gold standard’ in the treatment of opiate addiction.

4. GABA-BASED MEDICATION DISCOVERY

GABAergic hypothesis of drug reward

As noted above, an increase in mesolimbic DA transmission has been thought to underlie the drug reward produced by addictive drugs. However, how increased NAc DA mediates drug reward remains unclear. It is well documented that the neurotransmitter GABA plays an important role in the mesolimbic DA reward circuit [25, 123]. Anatomically, the majority of neurons in the striatum are medium-spiny GABAergic output neurons, which project predominantly to the dorsal globus pallidus (from the dorsal striatum) and the ventral pallidum (from the ventral striatum, i.e. the NAc) [124–126]. In addition, striatal GABAergic neurons also receive DA projections from the VTA and glutamatergic projections predominantly from the prefrontal cortex (PFC), and regulate striatal DA and glutamate release [28, 127]. Overall, DA produces an inhibitory effect on striatal medium-spiny GABAergic neurons [128–130], predominantly by activation of D2-like DA receptors [131, 132]. Similarly, psychostimulants, such as cocaine or amphetamine, produce an inhibitory effect on VTA GABAergic neurons [133], striatal GABAergic neurons [131, 132, 134–136], and on GABA release in the ventral pallidum (VP) [137–139]. Based on this, the VTA-NAc-VP pathway, particularly the downstream NAc-VP GABAergic projection, has been proposed as a common final pathway underlying psychostimulant reward [13–14, 17]. Thus, it has been hypothesized that any pharmacological strategy that increases GABAergic transmission by either elevating extracellular GABA levels or directly activating GABA receptors within brain reward circuits might directly counteract psychostimulant-induced inhibition of GABAergic neurons, thereby antagonizing psychostimulant abuse [123, 140, 141]. Based on this hypothesis, several GABAergic compounds, which are summarized in Table 3, are being explored as candidate medications for the treatment of psychostimulant addiction.

Table 3.

Pharmacological Actions of GABAergic Agents in Animal Models or Paradigms of Psychostimulant Addiction

| GVG | Gabapentin | Tiagabine | Topiramate | Baclofen | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacological Actions | GABA transaminase inhibitor | GABAmimetic | GABA transporter inhibitor | Positive GABAA receptor modulator | GABAB receptor agonist |

| Self-Administration (SA) | ↓ Cocaine SA (FR, PR) | No effect on cocaine SA | ↓ SA of low dose cocaine | ↓ Cocaine (amphetamine, METH) SA (FR, PR, 2nd-order) | |

| Reinstatement of Drug-Seeking | ↓ Relapse by cocaine | No effect on relapse by cocaine | No effect on relapse by cocaine | ↓ Relapse by cocaine, by amphetamine | |

| Conditioned Place Preference (CPP) | ↓ CPP by Cocaine or amphetamine | ↓ CPP by METH | |||

| Enhanced Brain-Stimulation Reward (eBSR) | ↓ eBSR by cocaine | ↓ eBSR by cocaine | |||

| Psychostimulant-like Discriminative Stimulus Effects (DS) | No effect on DS by cocaine | No effect on DS by cocaine | No effect on DS by cocaine | No effect on DS by cocaine | No effect on DS by cocaine |

| Behavioral Sensitization (BS) | ↓ BS by Cocaine | Conflicting | No effect on cocaine BS | ↓ BS by cocaine, by amphetamine | |

| Abuse Liability | No SA by itself | Cases reported | No cocain-like DS by itself | No cocain-like DS by itself | No SA by itself |

| Natural Reward | ↓ Food-taking

↓ Sucrose-seeking |

↓ Food-taking | ↓ Food-taking | ||

| Clinical Trials | Phase II | Phase I/II | Phase II | Phase II | Phase II |

4.1. Gamma-vinyl GABA (GVG)

GVG is an irreversible GABA transaminase inhibitor [142]. GABA transaminase is the primary enzyme involved in GABA’s metabolic breakdown, and therefore, and its inhibition elevates brain GABA levels. Since many anti-epilepsy and anticonvulsant medications are either direct or indirect GABA agonists, GVG (as an indirect agonist) was initially developed as an anticonvulsant, and has been used for that purpose in many countries for many years. About 10 years ago, Dewey and colleagues first proposed that GVG might be useful in the treatment of psychostimulant addiction by elevating brain GABA levels [140, 143]. So far, findings in their preclinical studies appear to be highly promising [12]. Systemic administration of GVG has been shown to inhibit: 1) cocaine-enhanced electrical BSR, but without significant effects on motor performance [144]; 2) cocaine self-administration under both FR5 and PR reinforcement [145, 146]; 3) cocaine-induced CPP [140]; 4) cocaine-induced behavioral sensitization [147]; and 5) cocaine-triggered reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior [146, 148]. In addition, at higher doses (~300 mg/kg), GVG also inhibits food-taking and sucrose-triggered reinstatement [145, 148, 149], but fails to inhibit the discriminative stimulus effects of cocaine [149].

Regarding the effects of GVG on NAc DA, previous studies by Dewey’s group have shown that GVG significantly inhibits cocaine- or cocaine-associated cue-induced increases in NAc DA in rats [140, 150–152]. However, our recent studies demonstrate that GVG, when given systemically or locally into the NAc, dose-dependently elevates NAc extracellular GABA levels, but fails to alter either basal levels of, or cocaine-enhanced, NAc DA in drug naïve or cocaine-treated rats [148]. The same doses of GVG also fail to inhibit, but rather increase, NAc extracellular glutamate levels (Xi et al., unpublished data). Clearly, these findings conflict with those from Dewey’s group noted above. The reasons for this discrepancy are unclear. It does not appear to be related to GVG dose, GVG pretreatment time or animals’ cocaine experience, but likely to be related to differences in rat strains (Long-Evans vs Sprague-Dawley) and/or brain regions of microdialysis sampling (medial NAc core/shell vs unspecified NAc subdomains) (see more discussion in [148]). Whatever the reasons for this discrepancy, our recent studies have further demonstrated that GVG-induced increases in NAc GABA are derived predominantly from non-neuronal (presumably glial) sources (Xi et al., unpublished data). This new finding provides a reasonable explanation for the ineffectiveness of GVG on NAc DA, i.e., that GVG-enhanced extrasynaptic GABA may not diffuse sufficiently into synaptic clefts to inhibit DA release. This is consistent with previous findings that local NAc perfusion of GABAA or GABAB receptor agonists, but not GABA itself, inhibits NAc DA and glutamate [127, 153, 154], and similarly inhibits cocaine or heroin self-administration and reinstatement of drug-seeking behaviors [154, 155]. GVG’s ineffectiveness on NAc DA suggests that non-DA mechanisms may underlie GVG-induced inhibition of drug-seeking behavior.

We have proposed an alternative mechanistic hypothesis - that GVG-elevated extracellular GABA levels in GABAergic projection loci such as the VP or VTA, may underlie GVG’s effects. That is, GVG-induced GABA elevations may directly counteract cocaine-induced reductions in GABA release, and therefore, may underlie the potential therapeutic effect of GVG on cocaine addiction [148]. This is consistent with our previous studies demonstrating that microinjection of GVG into the NAc failed to inhibit heroin self-administration, while microinjections of GVG into the VTA or VP significantly inhibited heroin self-administration [123].

Whatever the underlying mechanisms, the above-cited evidence strongly supports the potential use of GVG in the treatment of psychostimulant abuse. GVG is currently under double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trials for treatment of cocaine addiction. Preliminary open-label clinical trials demonstrated that GVG appears to manifest clinically-relevant anti-addiction, anti-craving, and anti-relapse properties in humans [156, 157]. The major concern for its use in humans, however, is the potential for visual field defects, which may limit its use.

4.2. Gabapentin

Gabapentin is structurally analogous to GABA but, unlike the latter, it crosses the blood–brain barrier and can be administered systemically [158]. Pharmacologically, gabapentin is a GABAmimetic drug that increases extracellular GABA levels, possibly by increasing the synthesis and nonvesicular release of GABA as well as by preventing GABA catabolism (reviewed in [159]). In addition, gabapentin also inhibits alpha2delta subunit-composed voltage-dependent Ca++ channels [160]. Early studies and small-scale, open-label outpatient trials suggested that gabapentin reduced cocaine craving and use [161–165]. However, this finding was later challenged by larger-scale, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials demonstrating that gabapentin, at doses up to 2400–3200 mg/day for 6–12 weeks, had no effect on abstinence rates, craving or subjective effects of cocaine [166–169].

Recently, we assessed its efficacy in animal models of drug addiction. We found that gabapentin (25–200 mg/kg i.p.) failed to inhibit i.v. cocaine self-administration under FR2 reinforcement or cocaine-triggered reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior in rats [170]. Congruent with our findings, Filip et al. [146] recently reported that lower doses of gabapentin (10–30 mg/kg, i.p.) neither alter cocaine self-administration nor cocaine-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior in rats. In addition, 1–30 mg/kg gabapentin was reported to have no effect on cocaine-induced hyperactivity or cocaine-induced behavioral sensitization [171, 172].

To study possible mechanisms underlying such ineffectiveness of gabapentin on cocaine’s addictive behaviors, we further observed the effects of gabapentin on NAc extracellular GABA, DA and cocaine-enhanced NAc DA in rats. We found that gabapentin, at 100–200 mg/kg, produced a modest increase (maximally ~50 %) in extracellular NAc GABA levels, but failed to alter either basal or cocaine-enhanced NAc DA [170]. This is in striking contrast to our findings with GVG in which we observed a robust and dose-dependent increase (200–400% at 100–300 mg/kg) in NAc extracellular GABA and an inhibition of both cocaine self-administration and cocaine-triggered reinstatement [148]. These data suggest that gabapentin is a weak GABA enhancer and has limited potential in the treatment of psychostimulant addiction.

4.3. Tiagabine

Tiagabine is a selective type 1 GABA transporter (GAT1) inhibitor, approved as an antiepileptic medication that increases synaptic levels of GABA. There are four types of GABA transporter identified, GAT1 being the most abundant, with predominant localization on GABAergic neurons and glial cells [173, 174]. Given the effectiveness of GVG in preclinical animal models of drug addiction, it was proposed that tiagabine may also be effective in attenuating cocaine use in humans [175]. However, the results of clinical trials with tiagabine are conflicting. Two small-scale (45 and 76 subjects, respectively) placebo-controlled clinical trials indicated that tiagabine produced a moderate reduction (~30%) in self-reported and urine-measured cocaine use in methadone-treated cocaine addicts [168, 175]. In contrast to this finding, other studies demonstrated that the same doses of tiagabine neither altered the acute effects of oral cocaine [176], nor significantly lowered cocaine use in human cocaine addicts [177, 178].

Similar conflicting findings are also reported in preclinical animal studies. It was reported that tiagabine produced a dose-dependent reduction in self-administration maintained by a very low dose (0.032 mg/kg) of cocaine under a FR10 schedule of reinforcement in baboons [179]. In contrast, Filip et al. [146] reported that tiagabine significantly inhibited lever responding for cocaine (0.5 mg/kg/infusion) self-administration under FR5 reinforcement, but had no effect on either total cocaine intake during self-administration, cocaine-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior, or cocaine’s discriminative stimulus effects. The reasons for such conflicting findings are unclear. Possibly, tiagabine’s binding properties could play a role. [3H]Tiagabine has highest binding density in frontal cortex and parietal cortex, and lowest binding in NAc and putamen [180]. Overall, present data suggest that tiagabine may have limited potential for the treatment of psychostimulant addiction.

4.4. Topiramate

GABAergic neurotransmission can be increased by drugs that elevate endogenous GABA levels (such as GVG, gabapentin or tiagabine) or by positive modulators at GABAA or GABAB receptors. Topiramate is a positive modulator of GABAA receptors, licensed as an antiepileptic drug. In addition to its enhancement of GABAA receptor-mediated currents at non-benzodiazepine sites on the GABAA receptor, topiramate also has other pharmacological actions in the brain, including antagonism of AMPA/kainate glutamate receptors, inhibition of voltage-gated sodium and calcium channels and inhibition of carbonic anhydrase [181]. Based on this, topiramate was proposed to be able to inhibit cocaine-enhanced NAc DA and cocaine abuse by enhancing GABAA-mediated inhibition and blocking excitatory glutamate activity [181, 182]. In a small preliminary clinical study (6 subjects), topiramate appeared to be effective at producing cessation of cocaine use, and alcohol consumption as well [183]. In another bigger double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial (40 subjects), topiramate significantly increased abstinance rates in patients with low cocaine withdrawal scores when compaired with placebo [184]. In contrast, a recent clinical report indicates that acute dosing with topiramate appears to enhance, rather than attenuate, the positive subjective effects of methamphetamine [185]. These data suggest that more large-scale clinical trials and preclinical mechanistic studies are required to determine whether or not topiramate is truly effective in antagonizing the addictive actions of psychostimulants.

4.5. Baclofen

Baclofen is a selective GABAB receptor agonist, licensed as an antispasmodic for patients with spinal cord injuries or multiple sclerosis. The efficacy of baclofen against cocaine use and relapse has been studied in both humans and animals extensively for many years, and appears promising for the treatment of cocaine addiction [186]. In rodents, pretreatment with baclofen dose-dependently attenuated cocaine-induced increases in NAc DA [187], cocaine-enhanced BSR [188], and cocaine self-administration under FR and PR reinforcement [189–191]. Baclofen also reduced cocaine-taking and cocaine-seeking behavior under second-order reinforcement in rats [192] and cocaine-triggered reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior [193, 194].

In an initial open-label clinical trial, baclofen (20 mg × 3) reduced self-reports of craving and cocaine use in 10 cocaine abusers [195]. In a subsequent 16-week double-blind study in 35 cocaine-dependent subjects, the same doses of baclofen reduced cocaine use and increased the number of cocaine-free urines [196], but did not significantly alter cocaine craving. In a recent placebo-controlled, double-blind study, baclofen (20 mg × 3/day, for 7 days) decreased self-administration of a low dose of smoked cocaine in 10 cocaine addicts, decreased cocaine craving in 7 opioid addicts, attenuated cocaine’s cardiovascular effects, but not cocaine’s subjective effects (‘high,’ ‘stimulated’) in both cocaine- and opioid-dependent subjects [197]. Another similar double-blind controlled study (7 subjects) demonstrated that a single dose of baclofen (10–30 mg/kg, p.o.) had no effect on either subject-rated or cardiovascular effects of intranasal cocaine [198]. Overall, baclofen seems to be well tolerated with no major side effects. The major limitation is its short-duration (3–4 hrs) of action, but slow-release preparations are likely to circumvent this limitation.

5. CANNABINOID-BASED MEDICATION DISCOVERY

Cannabinoid hypothesis of drug reward

Marijuana is the most widely used illicit drug in the United States and many other countries. As with other addictive drugs, cannabinoids produce significant rewarding and psychostimulating effects in both humans and experimental animals [199]. However, the underlying mechanisms are still unclear. The main psychoactive ingredient in marijuana is Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC). Two major types of cannabinoid receptors, CB1 and CB2, have been cloned [200, 201]. CB1 receptors are found primarily in the brain, whereas CB2 receptors are located mainly in peripheral tissues associated with the immune system [202, 203].

As discussed above, a GABAergic mechanism may underlie the rewarding effects of addictive drugs. Here, we propose that a similar cannabinoid-induced inhibition of GABAergic neurons in the mesolimbic system may also underlie the actions of cannabinoids. This is supported by the following evidence: first, previous studies show that Δ9-THC enhances NAc extracellular DA [204, 205], which may inhibit postsynaptic medium-spiny GABAergic neurons; and second, high densities of CB1 receptors are found on medium-spiny GABAergic neurons and glutamatergic terminals in the striatum [203, 206]. Since CB1 receptors are Gi-coupled, activation of CB1 receptors located on GABAergic neurons produces an inhibitory effect on GABAergic neurons. Similarly, activation of CB1 receptors located on glutamatergic terminals decreases glutamate release, thereby decreasing excitatory impact on striatal GABAergic neurons. Growing evidence demonstrates that cocaine, opioids, alcohol and DA significantly increase endocannabinoid release in the striatum [207–210], suggesting that such an increase in endocannabinoids release may contribute to the acute rewarding effects of psychostimulants by increasing endocannabinoid tone on CB1 receptors located on both medium-spiny GABAergic neurons and glutamate terminals. This endocannabinoid hypothesis of drug reward may explain why deletion or pharmacological blockade of CB1 receptors broadly affects almost all addictive drug actions in experimental animals [18, 211]. Based on this hypothesis, the selective CB1 receptor antagonists summarized in Table 4 could be effective in attenuating the rewarding effects and relapse properties of drugs of abuse, including psychostimulants.

Table 4.

Pharmacological Actions of CB1 Receptor Antagonists in Animal Models or Paradigms of Psychostimulant Addiction

| SR141716 | AM251 | |

|---|---|---|

| Pharmacological Actions | Prototypic CB1 receptor antagonist | Novel CB1 receptor antagonist |

| Self-Administration (SA) | Conflicting | ↓ Cocaine SA (PR, not FR)

↓ METH SA (FR) |

| Reinstatement of Drug-Seeking (Relapse) | ↓ Relapse by cocaine, cues, not stress | ↓ Relapse by cocaine |

| Conditioned Place Preference (CPP) | No effect on cocaine CPP | |

| Enhanced Brain-Stimulation Reward (eBSR) | ↓ eBSR by cocaine | ↓ eBSR by cocaine |

| Behavioral Sensitization (BS) | Conflicting | ↓ BS by cocaine |

| Natural Reward | ↓ Food-taking | ↓ Food-taking |

| Clinical Trials | Phase III for nicotine and alcohol, but not psychostimulant, dependence | No |

5.1. SR141716A

SR141716A [N-(piperidin-1-yl-5-(4-chlorophenyl)-1-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)-4-methyl-1H-pyrazole-carboxamide] is the first developed selective CB1 receptor antagonist [212], and has become a considerable focus for research on medication discovery for the treatment of drug abuse. It is well documented that SR141716A appears to be widely effective in attenuating self-administration of heroin, nicotine, or alcohol, and in attenuating reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior produced by these drugs [213–215]. However, the effects of SR141716A on cocaine’s actions have been controversial [216]. The positive findings include: 1) SR141716A (0.3–3.0 mg/kg i.p.) significantly inhibited cocaine- or cocaine-associated environmental cue-, but not footshock stress-, induced reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior [217, 218]; 2) SR141716A (0.3–3.0 mg/kg) dose-dependently lowered the break-point for cocaine self-administration under PR reinforcement conditions in mice [219]; and 3) SR141716 significantly inhibited cocaine-induced phasic increase in NAc DA in rats as assessed by in vivo voltammetry [220]. In contrast to these positive findings, most other studies demonstrate that SR141716A, within the dose range of 0.3–10 mg/kg, has no significant effect on: 1) cocaine self-administration under FR or PR reinforcement conditions in mice, rats or nonhuman primates [139, 217, 221–224]; 2) cocaine-induced CPP [225]; 3) cocaine’s discriminative stimulus effects [223]; 4) cocaine-enhanced BSR in rats [224]; 5) cocaine-induced behavioral sensitization [223, 225]; 6) cocaine-induced increases in NAc DA [139, 219]; and 7) cocaine-induced decreases in extracellular VP GABA levels [139]. These data suggest that SR141716A may have certain therapeutic potential in attenuating drug craving or relapse to drug-seeking behavior, but has limited potential in attenating cocaine’s acute rewarding and neurochemical effects [211, 216]).

5.2. AM251

AM251 [N-(piperidin-1-yl)-5-(4-iodophenyl)-l-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)-4-methyl-l-H-pyrazole-3-carboxamide] is a another CB1 receptor antagonist. Compared with SR141716A, AM 251 is roughly 2-fold more potent (Ki=7.49 vs. 11.5 nM) and more selective (1: 306 vs. 1: 143) than SR141716 for CB1 over CB2 receptors in vitro [226, 227]. The efficacy of AM251 on psychostimulant action has been assessed recently in preclinical animal models. In summary, it was reported that AM 251, within the dose range of 1–10 mg/kg i.p., dose-dependently inhibited: 1) methamphetamine (0.08 mg/kg/infusion) self-administration under FR3 reinforcement in rats [228]; 2) cocaine self-administration under PR, but not under FR2 reinforcement conditions in rats [224]; 3) cocaine-triggered reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior in rats [229]; 4) cocaine-enhanced electrical BSR in rats [224]; 5) cocaine- or amphetamine-induced behavioral sensitization in mice [230]; 6) cocaine-induced increases in NAc glutamate, but not in DA in rats [39]; and 7) cocaine-induced increases in phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase (p-ERK) [230]. In contrast to these positive findings, it was recently reported that, at lower doses (0.032–0.32 mg/kg i.v.), AM251 had no effect on methamphetamine-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior in rats [231].

Together, these data suggest that AM251 appears to be more potent and more effective in attenuating cocaine’s acute rewarding effects than SR141716. This is consistent with their in vitro binding properties noted above. In addition, the non-selective binding of SR141716A to other non-CB1 receptor proteins may also contribute to its relative ineffectiveness in attenuating cocaine’s rewarding efficacy (for more comprehensive review, see [211]).

Our most recent studies further demonstrate that a GABAergic mechanism within the NAc-VP GABAergic pathway appears to underlie AM251’s anti-reward action [211]. This is largely based on our recent finding that systemic cocaine produced a significant and dose-dependent increase in extracellular DA in both the NAc and VP, but a dose-dependent reduction in extracellular GABA levels in the VP. Pretreatment with AM251, when administered systemically or locally into the VP, dose-dependently blocked cocaine-induced reductions in VP GABA levels, but had no effect on cocaine-induced increases in NAc or VP DA levels. In contrast to AM251, SR141716 significantly inhibited cocaine-induced reductions in VP GABA levels when administered locally, but not systemically [211]. In addition to this GABAergic mechanism, a glutamate-mGluR2/3-dependent mechanism may also underlie the antagonism of AM251 or SR141716 on cocaine-triggered reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior [229]. Briefly, CB1 receptor blockade-induced increases in NAc glutamate leads to an increase in glutamate tone on mGluR2/3 auto-receptors on glutamatergic terminals, which subsequently inhibits cocaine-induced increases in NAc glutamate release and cocaine-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking behaviors [211, 229].

Taken together, these data support an important role for CB1 receptors in cocaine reward and relapse. AM251 or other more potent and more selective CB1 receptor antagonists appear promising for the treatment of psychostimulant addiction. The effectiveness of AM251 in attenuating cocaine’s rewarding effects also supports the endocannabinoid hypothesis of drug reward proposed above.

6. GLUTAMATE-BASED MEDICATION DISCOVERY

Glutamate hypothesis of drug reward

L-glutamate is the major excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain and acts through two heterogeneous families of glutamate receptors: ionotropic (iGluR) and metabotropic (mGluR). While iGluRs (i.e. NMDA, AMPA, kainate) are ligand-gated ion channels and responsible for fast excitatory neurotransmission, mGluRs (mGluR1–8) are G-protein coupled receptors linked to intracellular second messenger pathways. The eight subtypes of mGluRs have been classified into three groups on the basis of sequence similarities and pharmacological properties. Group I (mGluR1,5) receptors activate phospholipase C via Gαq/11 proteins, whereas group II (mGluR2,3) and group III (mGluR4,6,7,8) receptors inhibit adenylate cyclase via Gαi/o proteins [232].

The role of NAc glutamate in mediating cocaine’s rewarding effects is controversial. Growing evidence suggests that NAc glutamate transmission is negatively correlated to brain reward function and/or psychostimulant’s rewarding effects. This view is supported by the following evidence: 1) repeated cocaine injections or cocaine self-administration produces long-term depression in basal glutamate transmission in the mouse NAc [233, 234]; 2) chronic cocaine self-administration produces a significant reduction in basal levels of extracellular glutamate in the rat NAc, an effect that persists for 5 days after the extinction of cocaine self-administration [235]; 3) repeated cocaine administration results in a decrease in glutamate immunoreactivity in presynaptic NAc terminals [236, 237]; 4) microinjections of NMDA receptor antagonists (phencyclidine, MK-801) produce an enhancement of electrical BSR in rats [238, 239]; further, NMDA receptor antagonists are self-administered locally into the NAc [240]; 5) systemic administration of MK-801 increases cocaine’s rewarding efficacy, as assessed by an increase in break-point levels for cocaine self-administration under PR reinforcement conditions [241]; 6) activation of presynaptic mGluR2/3 receptors, which inhibits glutamate release, enhances amphetamine reinforcement in amphetamine-sensitized rats [242], while mGluR2/3 antagonists, which facilitate glutamate release, discrupt intra-NAc amphetamine-induced CPP [243]; 7) genetic deletion or pharmacological blockade of mGluR5, which results in an increase in extracellular NAc glutamate, inhibits cocaine self-administration and cocaine-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior [244] (see more discussion in section 6.2. below); and 8) electrical stimulation of PFC, which increases NAc glutamate release, or increased GluR1 expression in the NAc, inhibits cocaine self-administration and cocaine-triggered reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior [245, 246]. These findings suggest that an increase in NAc glutamate transmission may attenuate, while a reduction in glutamate transmission may significantly contribute to, the rewarding effects produced by cocaine or amphetamine.

In contrast to these findings, other studies suggest an important role of enhanced glutamate transmission in mediating cocaine reward (for review, see [247]). The major evidence includes: 1) high doses of cocaine (30 mg/kg) or amphetamine (2 mg/kg) produce an increase in extracellular glutamate in the NAc in drug naïve rats [248, 249]; and 2) activation of NAc AMPA or NMDA receptors appears to enhance cocaine’s rewarding effect as suggested by a compensatory reduction in cocaine self-administration behavior [250], while blockade of AMPA or NMDA receptors attenuate cocaine self-administration and cocaine- or amphetamine-induced CPP [250–253].

Glutamate hypothesis of relapse

It is well documented that drug craving and reinstatement (relapse) of cocaine-seeking behavior are related to repeated cocaine-induced reduction in basal levels of glutamate transmission in the NAc during cocaine withdrawal or abstinence and to enhanced glutamate responses to acute cocaine priming (largely due to a reduction in basal levels of glutamate) [16, 127, 155, 233, 235, 254, 255]. In addition, such glutamate responses also can be seen in the presence of cocaine-associated environmental cues or footshock stress [256–258]. These data suggest that both a reduction in basal glutamate transmission and enhanced glutamate responding may constitute a neurobiological substrate of cocaine-, cocaine-associated cue-, or stress-triggered relapse. Such preclinical findings suggest a number of potential pharmacotherapeutic strategies (summarized in Table 5): first, normalization (increase) of reduced basal glutamate neurotransmission might be helpful in attenuating cocaine reward and relapse; and 2) blockade of enhanced glutamate responses to cocaine priming, cocaine-associated cues, or stress might attenuate reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior evoked by these relapse-triggers.

Table 5.

Pharmacological Actions of Glutamate Agents in Animal Models or Paradigms of Psychostimulant Addiction

| N-Acetylcysteine | MPEP | LY379268 | 2-PMPA | AMN082 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacological Actions | Cystine prodrug, glutathione prodrug | mGluR5 antagonist | mGluR2/3 agonist | NAALADase inhibitor | mGluR7 agonist |

| Self-Administration | No effect on cocaine SA | ↓ Cocaine SA (FR, PR) | ↓ Cocaine SA (FR) | ↓ Cocaine SA (PR, notFR) | ↓ Cocaine SA (FR, PR) |

| Reinstatement of Drug-Seeking | ↓ Relapse by cocaine | ↓ Relapse by cocaine, by cues, but not by stress | ↓ Relapse by cocaine or cues | ↓ Relapse by cocaine | ↓ Relapse by cocaine |

| Conditioned Place Preference (CPP) | ↓ CPP by cocaine, amphetamine or MDMA | ↓ CPP by cocaine | |||

| Enhanced Brain-Stimulation Reward (eBSR) | Conflicting | ↓ eBSR by cocaine | ↓ eBSR by cocaine | ||

| Psychostimulant-like Discriminative Stimulus Effects (DS) | ↓ DS by cocaine | ||||

| Behavioral Sensitization (BS) | ↓ BS by cocaine | ↓ BS by cocaine | ↓ BS by amphetamine | ↓ BS by cocaine | |

| Natural Reward | ↓ Food-taking | ↓ Food-seeking | No effect on CPP for food | No effect on sucrose-taking | |

| Clinical Trials | Phase I | No | No | No | No |

6.1. N-acetylcysteine

N-acetylcysteine is a cystine prodrug. Recently, it was reported that systemic administration of N-acetylcysteine or local perfusion of cystine itself into the NAc restored decreased NAc glutamate levels in chronic cocaine-treated rats by stimulating cystine-glutamate exchange (i.e. exchange of extracellular cystine for intracellular glutamate), and dose-dependently inhibited cocaine-triggered reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior [255, 259]. Although N-acetylcysteine did not inhibit cocaine self-administration or acute cocaine-induced hyperactivity, it inhibited escalation of drug intake and behavioral sensitization seen after repeated administration [259]. In addition, pretreatment with N-acetylcysteine inhibited cocaine-induced increases in NAc glutamate by a mechanism that increased glutamate tone on presynaptic mGluR2/3 receptors [229, 255, 260, 261]. Also of interest is the fact that N-acetylcysteine is also a prodrug for the synthesis of the endogenous antioxidant glutathione, and that N-acetylcysteine pretreatment protected animals from high dose methamphetamine- or amphetamine-induced DA neurotoxicity and behavioral changes by lowering oxidative stress levels [262–265].

N-acetylcysteine is currently under Phase I trial for the treatment of cocaine addiction. So far, N-acetylcysteine appears to be safe and well tolerated as observed in 13 cocaine addicts [266]. An open-label clinical trial demonstrated that N-acetylcysteine, at 2400–3600 mg/day for 4 weeks, significantly reduced cocaine use in 16 of 23 human cocaine-addicted subjects [267]. Similarly, another double-blind, placebo-controlled trial demonstrated that N-acetylcysteine (600 mg/12 h × 4) significantly inhibited desire to use cocaine, interest in cocaine, or cue viewing time triggered by exposure to cocaine-related cues in 15 cocaine-addicted participants during a 3-day hospitalization study [266].

6.2. MPEP

MPEP [2-methyl-6-(phenylethynyl)-pyridine] is a selective group I mGluR5 antagonist. The mGluR5 receptor has become an important target in medication discovery for treatment of psychostimulant addiction, largely because of its relatively selective regional distribution in the NAc [268]. A large body of literature indicates that mGluR5 plays an important role in behavioral responses to psychostimulants [269]. Systemic administration of MPEP significantly attenuated the rewarding effects of psychostimulants, as assessed by: 1) cocaine self-administration under FR or PR reinforcement in mice, rats and nonhuman primates [24, 270–276]; and 2) cocaine-, amphetamine- or MDMA-induced CPP in rats [277, 278]; MPEP also attenuated cocaine- or amphetamine-induced hyperactivity in rats or mice [279–281]. In addition, MPEP pre-treatment inhibited reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior triggered by cocaine in rats and nonhuman primates [271,272,276] or by cocaine-associated cues in rats [282,283], but not by footshock stress [272].

To further determine the site(s) of action of MPEP and the neurochemical mechanisms underlying the antagonism by MPEP of cocaine’s actions described above, we microinjected MPEP into the NAc in conjunction with cocaine-triggered relapse. We found that intra-NAc MPEP (3–10 μg/side) significantly inhibited cocaine-triggered reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior (Xi et al., unpublished data). These data suggest that the NAc is an important site underlying MPEP’s anti-relapse action. Further, in vivo microdialysis studies demonstrated that MPEP itself selectively elevated NAc extracellular glutamate, but not DA levels. Further, pretreatment with MPEP selectively prevented cocaine-induced increases in NAc glutamate, but not in NAc DA [271]. Such increased NAc glutamate produced by MPEP is tetrodotoxin (TTX)-insensitive, suggesting non-vesicular glutamate origins. We believe that this increase in NAc glutamate by MPEP may play an important role in attenuating cocaine reward and relapse, likely by attenuating cocaine-induced reduction in VP GABA release, renormalizing reduced basal levels of glutamate transmission, and potentiating mGluR2/3-mediated inhibition of cocaine-enhanced glutamate responding as discussed above. Taken together, these preclinical data suggest that the mGluR5 antagonist MPEP could be promising in the treatment of psychostimulant addiction. So far, however, no clinical trials with MPEP have been undertaken.

6.3. LY379268

LY379268 [(−)-2-oxa-4-aminobicylco [3.1.0] hexane-4,6-dicarboxylic acid] is a selective and systemically effective group II receptor (mGluR2/3) agonist [284]. Recently, mGluR2/3 receptors have become attractive targets in medication development for the treatment of drug addiction because group II mGluR2/3 receptors function as glutamate autoreceptors, and mGluR2/3 activation inhibits glutamate release from neuronal and/or glial cells [285,286]. In addition, mGluR2/3 activation inhibits the release of other striatal neuro-transmitters, including DA [232,287]. Also, in comparison to other mGluRs, mGluR2/3 are highly expressed in the NAc, hippocampus and PFC [268], suggesting that the mGluR2/3 could be a target on which cocaine acts. Given that cocaine-induced increases in NAc DA and glutamate have been thought to play an important role in drug reward and relapse, it has been proposed that mGluR2/3 agonists could be effective in the treatment of cocaine addiction [285,286,288].

With the recent development and widespread use of LY379268, its efficacy in animal models of drug addiction has been recently studied. It has been reported that: 1) systemic administration of LY379268 significantly inhibits both acute and sensitized locomotor behaviors induced by amphetamine [289,290]; 2) systemic administration of LY379268 inhibits cocaine self-administration and cocaine-associated cue-triggered reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior [291]; 3) systemic administration or microinjection of LY369268 into the NAc core significantly inhibits cocaine- or food-triggered reinstatement of reward-seeking behavior [292]; 4) systemic or local administration of LY379268 into the central amydala inhibits incubation of cocaine craving in rats [293]; and 5) systemic or intra-NAc administration of LY379268 inhibits heroin-associated contextual cue-triggered reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior [294,295]. Together, these data suggest that mGluR2/3 agonists may be promising in the development of anti-cocaine medications.

6.4. 2-PMPA

2-PMPA [2-(Phosphono-methyl)-pentanedioic acid] is a highly potent and selective inhibitor of the enzyme N-acetylated-α-linked acidic dipeptidase (NAALADase), which hydrolyzes N-acetylaspartate-glutamate (NAAG) to N-acetylaspartate (NAA) and glutamate [296]. NAAG is an endogenous mGluR3 agonist, which negatively modulates the release of glutamate and other neurotransmitters [297]. At high concentrations, NAAG may also act as a mixed agonist/antagonist of NMDA receptors [298]. In addition to functioning as an mGluR3 agonist, NAAG may also serve as a glutamate precursor, because it can be hydrolyzed by the enzyme NAALADase to NAA and glutamate. Immunohistochemical studies have shown that NAAG is located in neurons [299,300] and released in a Ca++-dependent manner [301], while NAAL-ADase and its mRNA are located primarily in astrocytes [302, 303]. This suggests that synaptically released NAAG is degraded by NAALADase predominantly located on astrocytic membranes. Thus, NAALADase appears to be a key enzyme regulating extracellular glutamate and neuronal glutamate availability [297]. Given the important role of NAc glutamate in drug reward and relapse, it has been hypothesized that a NAALADase inhibitor, such as 2-PMPA, may be a promising anti-cocaine medication - acting by inhibiting cocaine-induced increases in NAc DA and glutamate via mGluR3 receptors, secondary to an increase in extracellular NAAG levels [304, 305].

Previous studies have shown that systemic administration of 2-PMPA significantly inhibits cocaine-induced CPP [306] and cocaine-induced behavioral sensitization [307]. Recently, we have shown that systemic administration of 2-PMPA, within a low dose window, significantly inhibited: 1) cocaine self-administration under a PR, but not FR2, reinforcement schedule; 2) cocaine-enhanced BSR; and 3) cocaine-triggered reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior [304, 305]. The same doses of 2-PMPA alone had no effect on BSR. These data suggest that inhibition of NAALADase by 2-PMPA produces an inhibitory effect on cocaine’s rewarding effects and cocaine-triggered reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior.

To further determine the neurochemical mechanisms underlying these behavioral effects, we observed the effects of 2-PMPA on NAc DA, glutamate and GABA using in vivo brain microdialysis. We found that systemic administration of 2-PMPA (10–100 mg/kg, i.p.) dose-dependently decreased NAc extracellular DA, glutamate and GABA levels, an effect that was blocked by intra-NAc perfusion of the mGluR2/3 antagonist LY341495 (Xi et al., unpublished data). These data suggest mediation by activation of NAc mGluR3 receptors secondary to an increase in NAAG levels. This is consistent with previous findings that mGluR2/3 activation inhibits the release of DA, glutamate, GABA and many other neurotransmitters in the brain [232]. This nonselective inhibition of neurotransimitter release may explain the “dose-window” effectiveness of 2-PMPA in animal models of drug addiction noted above, and also suggests a potential limitation for the use of 2-PMPA or other mGluR2/3 agonists in the treatment of addictive diseases. So far, no clinical trials with drugs from this receptor-active category have been undertaken.

6.5. AMN082

AMN082 [N,N′-Bis(diphenylmethyl)-1,2-ethanediamine dihydrochloride] is a selective systemically effective mGluR7 agonist [308]. The mGluR7 receptor subtype is of particular interest, because: 1) mGluR7 is the most abundant subtype among group III mGluR receptors in reward-related brain regions such as striatum, hippocampus and olfactory tubercle [268]; 2) mGluR7 is the most highly conserved mGluR subtype across different mammalian species [309], suggesting that selective mGluR7 ligands that are effective in laboratory animals are more likely to be effective in humans; and 3) microinjections of L-AP4, a non-selective brain-impermeable group III mGluR agonist, into the NAc or dorsal striatum inhibit NAc DA and glutamate [287, 310], and cocaine-induced increases in striatal DA and locomotion [311, 312]. These data may imply a potential role for mGluR7 in the modulation of drug-taking and drug-seeking behaviors. However, the role of group III receptors in drug reward and relapse is comparatively unstudied because of lack of selective pharmacological tools.

With the recent availability of the systemically effective mGluR7-selective agonist AMN082, we have assessed AMN082’s actions in animal models of drug addiction. We found that systemic administration of AMN082 (1–20 mg/kg i.p.) dose-dependently inhibits: 1) cocaine self-administration behavior under both FR2 and PR reinforcement schedules; 2) cocaine-enhanced BSR; and 3) cocaine-triggered reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior. In contrast, the same doses of AMN082 had no effect on locomotion or sucrose self-administration behavior. AMN082 alone, at lower doses (1–10 mg/kg), did not alter BSR itself, while a higher dose (20 mg/kg) decreased BSR in an aversive-like manner [313].

To further determine the mechanisms underlying these effects, we observed the action of AMN082 alone or in combination with cocaine on NAc DA, glutamate and GABA using in vivo brain microdialysis. We found that AMN082 significantly lowered NAc extracellular GABA, increased extracellular glutamate, but had no effect on NAc DA levels [314]. Further, pretreatment with AMN082 did not inhibit cocaine-enhanced NAc DA [313], suggesting that a DA-independent mechanism underlies the observed behavioral effects. Consistent with the GABAergic hypothesis of drug reward discussed above, a decrease in NAc GABA and an increase in glutamate would increase NAc medium-spiny GABAergic neuronal activity, thereby counteracting cocaine-induced GABAergic inhibition and cocaine reward. In addition, AMN082-induced increases in NAc glutamate may also restore decreased basal levels of extracellular glutamate, and increase glutamate tone on presynaptic mGluR2/3 receptors, thereby inhibiting cocaine priming-induced increases in NAc glutamate and cocaine-triggered reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior. Together, these preclinical experimental data suggest a potential utility for AMN082, a selective mGluR7 agonist, in the treatment of cocaine or other psychostimulant addiction.

6.6. Modafinil