Abstract

Objectives

This study attempted to evaluate whether impulsive sensation seeking mediated the relationship between parental alcohol problems and offspring alcohol and tobacco use.

Methods

Participants were Connecticut high school students (n = 2733) completing a survey of high-risk behaviors. Variables of interest included past month alcohol use, past month binge alcohol use, frequency of past month alcohol use, past month tobacco use, having a biological parent with an alcohol problem, and score on the impulsive sensation seeking (ImpSS) scale from the Zuckerman-Kuhlman Personality Questionnaire – Form III.

Results

ImpSS scores were elevated in past month users of alcohol, binge users of alcohol, users of both tobacco and alcohol, and they increased with increasing frequency of past month alcohol use. Also, parental history of alcohol use increased the likelihood of past month alcohol use, binge use, use of both tobacco and alcohol, and higher levels of past month alcohol use. Mediational analyses did not appear to support the hypothesis that impulsive sensation seeking mediates the relationship between parental history of alcohol problems and alcohol and tobacco use in offspring.

Conclusions

Impulsive sensation seeking and parental history of alcohol problems appear to be independent factors that contribute to the co-occurrence of alcohol and tobacco use in adolescents. These findings can inform prevention and treatment efforts.

Keywords: Alcohol, tobacco, adolescent, impulsive behavior, sensation seeking

Impulsivity and sensation seeking are personality traits that appear to influence risk-taking generally, and substance use processes more specifically. Moeller and colleagues1 have defined impulsivity as a tendency to act quickly without thinking ahead about consequences; Zuckerman2 has defined sensation seeking as a tendency to take risks in order to seek out novel, stimulating experiences. Both impulsivity and sensation seeking are positively correlated with current alcohol use and current heavy episodic alcohol use among adults and adolescents,3–6 and both traits have been hypothesized to play a role in the initiation of alcohol use and in alcohol use disorder (AUD) development.7, 8

Among adolescents, higher sensation seeking levels have been associated with regular alcohol use in a large cross-national sample,9 and appear to predict longitudinal increases in alcohol use over a three year period.10 Furthermore, it appears that interventions that target sensation seeking in adolescents can delay the onset and progression of alcohol use and binge use.11 In all, sensation seeking appears to exert direct and indirect promotional effects on alcohol use,3, 12, 13 and a meta-analysis using 61 pooled studies found that sensation seeking had a small to moderate effect size on promoting alcohol use.14

Examinations of impulsivity have also found that it is associated with elevated or problem alcohol use in different populations. To illustrate, adolescents with AUDs have higher levels of trait impulsivity,15 and hazardous drinkers appear to be more impulsive than social drinkers.16 Impulsivity has been associated with trajectories of higher binge alcohol use in college students,17 and individuals who began alcohol use in adolescence have higher levels of impulsive responding on a behavioral task than those who began use at 21 years of age or older.18 Finally, a prospective study of the relationship between impulsivity and alcohol or tobacco use found that impulsivity was related to both alcohol and tobacco use at baseline and that increasing baseline levels of impulsivity predicted increases in both alcohol and tobacco use.19

Another characteristic that has been associated with an elevated risk for alcohol problems is the presence of a parental history of alcoholism. Specifically, children of parents with a history of alcohol problems have greater numbers of problem drinking symptoms20 and are more likely to be on a problem drinking trajectory,21 consume alcohol in a binge fashion22 and have an AUD23, 24 than individuals with no family history of alcohol problems. Sher25 estimated that children of alcoholic parents were between two and ten times more likely to develop alcoholism than children of parents without alcohol problems. Children of alcoholics also have higher rates of tobacco use and dependence than those without a parental history,26–28 and they appear to have an elevated risk for comorbid alcohol and tobacco dependence.27

Furthermore, individuals with a family history of alcoholism also appear to have elevated levels of sensation seeking.29–31 Elkins and collaborators32 found that certain personality traits that may raise the risk for problem alcohol use are present in children of alcoholics who have not developed alcohol problems, and Swendsen and colleagues33 found evidence that personality traits may compose a portion of the risk inherited by children of alcoholics. While neither study examined sensation seeking specifically, both lend evidence to the possibility that personality traits may mediate the relationship between parental alcohol problems and later alcohol problems among offspring. Sensation seeking could function in that fashion by mediating the effects of having a parental history of alcohol problems on adolescent alcohol use.

Indeed, Schuckit and collaborators34 found that disinhibition (as a component of sensation seeking) was an important mediating factor between family history and drinking status by increasing the likelihood of associating with peers who consumed alcohol and by increasing positive expectations for alcohol.34 Alternatively, Gruzca and coauthors35 found that novelty seeking, which is related to sensation seeking, moderated the relationship between a history of alcohol problems in a sibling and index alcohol problems. Probands with an alcohol dependent sibling who have high novelty seeking are at higher risk for alcohol dependence, whereas low novelty seeking may be protective in those with alcohol dependent siblings. Thus, while sensation seeking traits appear to promote alcohol use and problem use among those with a familial history of alcohol problems, it is unclear whether sensation seeking mediates this relationship.

Proceeding from the findings of Schuckit et al.,34 Gruzca et al.,35 and others,32, 33 this study attempted to examine whether impulsive sensation seeking, as assessed by the Impulsive Sensation Seeking scale (ImpSS) from the Zuckerman-Kuhlman Personality Questionnaire,36 mediated the relationship between parental history of alcohol problems and frequency of alcohol use, binge alcohol use, and concomitant alcohol and tobacco use. Given that the roles of impulsivity and sensation seeking in the progression of alcohol use in adolescents and in mediating the relationship between parental history of alcohol problems and proband alcohol use are still unclear, we chose to use a combined variable (ImpSS), as opposed to variables for impulsivity and sensation seeking separately. As the ImpSS has subscales for both impulsivity and sensation seeking, separate testing of each component could occur if the overall scale is a significant mediating variable. The ImpSS scale has been used to evaluate alcohol use and other risk behaviors among adolescents,5 and it appears to be a valid assessment of these traits.

In order to evaluate the relationships between these variables, data from a cross-sectional survey of high-risk behaviors conducted in ten Connecticut high schools were used. The sample of older adolescents was chosen based on a desire to measure the relationships between alcohol use, parental history of alcohol use and impulsive sensation seeking as, developmentally speaking, alcohol use increases. That said, it was expected that any confounding sequelae of heavy alcohol use (e.g., increased impulsivity or sensation seeking) would be limited in this age group, and we believed it was important to assess these relationships in a population where early intervention was still possible. Finally, we included current tobacco use given its common concurrent use with alcohol in adolescents and the public health importance of concurrent use in this population.37–39

We had four hypotheses: 1) ImpSS scores would be positively associated with frequency of alcohol use, binge use, and concomitant alcohol and tobacco use; 2) both parental history of alcohol problems would be associated significantly with the alcohol use variables and concomitant alcohol-tobacco use; 3) ImpSS scores would be elevated in adolescents with a parental history of alcohol problems, as compared to those without a parental history; and, 4) impulsive sensation seeking would mediate a portion of the relationship between parental history of alcohol problems and the four alcohol and tobacco use outcome variables: frequency of alcohol use, binge alcohol use, and concomitant alcohol and tobacco use.

Methods

Study Procedures and Sampling

The study team sent invitation letters by mail to all public four-year and non-vocational or special education high schools in the state of Connecticut. These letters were followed by phone calls to all principals of schools receiving a letter to assess the school’s interest in participating in the survey. In order to encourage participation, all schools were offered a report following data collection that outlined the prevalence of the queried risk behaviors in that school. Schools that expressed an interest were contacted to begin the process of obtaining permission from School Boards and/or school system superintendents, if this was needed. In many cases, the process of obtaining permission required the presentation of a specific proposal to the School Board at a regularly scheduled meeting of the board.

After the initial round of letters was mailed, the response from schools was not yet sufficient to ensure that all regions of the state were sufficiently represented. Therefore, targeted contacts were made to schools that were in geographically underrepresented areas to ensure that the sample was representative of the state. The final survey contains schools from each geographical region of the state of Connecticut, and it contains schools from each of the three tiers of the state’s district reference groups (DRGs). DRGs are groupings of schools based on the socioeconomic status of the families in the school district. Sampling from each of the three tiers of the DRGs was intended to create a more socioeconomically representative sample. Although this was not a random sample of public high school students in CT, the sample obtained in this study is similar in demographics to the sample of CT residents enumerated in the 2000 Census ages 14–18.

Once permission was obtained from the necessary parties in each school, a passive consent procedure was developed. Letters were sent through the school to parents informing them about the study and outlining the procedure by which they could deny permission for their child to participate in the survey if they wished their child to be excluded. In most cases, parents were instructed to call the main office of their child’s high school to deny permission for their child’s participation. From these phone calls, a list of students who were not eligible to participate was compiled for use on the survey administration day. If no message was received from a parent, parental permission was assumed. The passive consent procedure was approved by all participating schools and by the Institutional Review Board of the Yale University School of Medicine.

In most cases, the entire student body was targeted for administration of the survey. Some schools conducted an assembly where surveys were administered, while others had students complete the survey in every health or English class throughout the day. In each case, the school was visited on a single day by a number of research staff who explained the study, distributed the surveys, answered questions, and collected the surveys. Students were told that participation was voluntary and that they could refuse to complete the survey if they wished, and were also reminded to keep surveys anonymous by not writing their name or other identifying information anywhere on the survey. Students were given a pen for participating. If a student was not eligible to participate because a parent had denied permission, this student worked quietly on other schoolwork while the other students completed the survey. Data were double-entered from the paper surveys into an electronic database. Data cleaning procedures were performed to ensure that data were not out of range. In addition, random spot checks of the completed surveys were performed to ensure the accuracy of data entry.

Measures

The survey consisted of 153 questions concerning demographic characteristics, substance use, other risk behaviors, and the impulsive sensation seeking scale (ImpSS) from the Zuckerman-Kuhlman Personality Questionnaire.36 For these analyses, questions assessing alcohol and cigarette use behaviors, family history of alcohol problems and the ImpSS scale were used. To assess alcohol use, participants were asked if they had ever had a “full” drink of alcohol; students who responded yes were asked a series of questions about their current alcohol use patterns. The variables chosen from the set on alcohol use behaviors were the number of days the students consumed alcohol in the past month (recoded into groups of 0 days, 1 or 2 days, 3 to 9 days and 10 or more days of alcohol use) and whether the participant had any alcohol binge use episodes in the past month (a binge was defined as “5 or more drinks of alcohol in a row” or five or more drinks “within a couple of hours”). Tobacco use was assessed as any past month use; for the combined assessment of concomitant alcohol and tobacco use, participants could be classified as using neither substance (non-users), users of alcohol only, users of tobacco only, or users of both.

Parental alcohol problem history was assessed through the following question: “Has anyone in the family you live with ever had an alcohol problem? Check ALL that apply.” Responses were put in the following categories: biological parent, adoptive or step-parent, brother or sister, grandparent or some other family member. Given that all of the other categories allowed for family members that may not have been genetically related to the participant, students were grouped according to their response as to whether a biological parent had a history of alcohol problems. Slutske and collaborators40 found that a similar single-measure item assessing parental alcohol problems had good to excellent interrater reliability in a sample of twin pairs, and Cuijpers and Smit41 found that a very similar single item assessment of alcohol problems had strong concurrent validity with a larger measure, the FH-RDC. Finally, the ImpSS scale is a 19 question true-false scale assessing various personality characteristics and behaviors related to impulsivity and sensation seeking, and it is scored by summing the items that are consistent with impulsivity or sensation seeking. Thus, scores for this scale range from 0 to 19. The ImpSS scale has good internal validity, face validity and concurrent validity with other measures of personality such as the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire-Revised.36

Data Analysis

Distribution characteristics of all variables were examined. Only participants with complete data (including a complete ImpSS scale) were included in analyses. Also, baseline demographic data was evaluated for differences between those with complete data and those without complete data using t-tests for parametric data and Mann-Whitney U tests for nonparametric data. Primary analyses were conducted in four parts to evaluate the relationships between impulsive sensation seeking, parental history of alcohol problems and current use of alcohol and/or tobacco. First, the relationships of impulsive sensation seeking and the alcohol use variables and the concomitant alcohol-tobacco use variable were evaluated using univariate general linear model (GLM) analyses. To illustrate group differences in impulsive sensation seeking based on frequency of alcohol use, Bonferonni-corrected post hoc comparisons were used. Second, the relationships of parental alcohol problems and the alcohol use variables and the concomitant alcohol-tobacco use variable were tested using regression models. For the past month binge use variable, a logistic regression was performed; for the frequency of past month alcohol use and the concomitant alcohol-tobacco use variable, multinomial regressions were performed.

After establishing that each independent variable (i.e., impulsive sensation seeking and parental history of alcohol problems) was related to the outcome variables, the two independent variables must be related in order to establish mediation. To examine this possibility, the relationship of impulsive sensation seeking and parental history of alcohol problems was evaluated using univariate GLM analysis. Finally, the possibility of mediation was tested by examining the relationship of parental history of alcohol problems and alcohol use variables and the concomitant alcohol-tobacco use variable while controlling for impulsive sensation seeking levels. Logistic or multinomial regressions were used for these analyses, as appropriate. Significance level was set at p < .01 for all analyses. A more conservative level (than p < .05) was chosen because of the large sample available for analyses and the desire to avoid type I error.

Results

Demographic Characteristics

The demographic characteristics of the entire survey sample, and the characteristics of the sample split into those with complete data and those without complete data are summarized in Table 1. Of the 4523 adolescents who participated in the survey, 2733 (60.4%) had complete data for the analyses conducted here. Of those 1790 adolescents with missing data, 624 (34.9% of those with missing data) were only missing data on current alcohol use patterns, 880 (49.2% of those with missing data) were missing data from the impulsive sensation seeking scale and 286 (16.0% of those with missing data) were missing data from both. Comparisons of subjects with complete data and those without complete data revealed that students with complete data were more likely to be female, slightly older, in a later grade (i.e., 11th or 12th grades), of medium or higher income, and of Caucasian ethnicity and were less likely to be of Hispanic/Latino, African-American or “Other” descent. These data are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics for Completers and Non-Completers

| All Participants | Participants with Complete Data | Participants without Complete Data | Significance Testing | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 52.5% female | 54.5% female | 49.3% female | Z = −3.38; p = .001 |

| Age | 15.87 (mean), 1.27 (SD) | 15.93 (mean), 1.23 (SD) | 15.78 (mean), 1.33 (SD) | t = −3.75; p < .001 |

| Grade in School | Z = −6.50; p < .001 | |||

| 9th | 30.7% | 27.4% | 35.5% | |

| 10th | 27.6% | 27.0% | 28.3% | |

| 11th | 25.7% | 28.5% | 21.5% | |

| 12th | 16.0% | 17.1% | 14.4% | |

| Average Grades | Mostly B’s (median) | Mostly B’s (median) | Mostly B’s (median) | Z = −1.39; p = .166 |

| Ethnicity* | ||||

| Caucasian | 74.4% | 78.4% | 68.2% | Z = −6.71; p < .001 |

| African-American | 11.1% | 8.6% | 15.0% | Z = −7.71; p < .001 |

| Asian | 4.1% | 4.0% | 4.2% | Z = −0.43; p = .669 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 15.0% | 13.2% | 17.9% | Z = −4.24; p < .001 |

| Other Ethnicity | 14.3% | 13.4% | 18.2% | Z = −4.40; p < .001 |

= Ethnicity categories are non-exclusive (i.e., students were asked to select as many ethnic categories as applied to them); totals do not add up to 100%

In terms of current alcohol and tobacco use patterns among the adolescent participants, 1120 (41.0%) adolescents used neither alcohol nor tobacco, 82 used tobacco only (3.0%), 974 used alcohol only (35.6%), and 557 (20.4%) used both substances. Analyses indicated differences in age, grade in school, median grades in classes, ethnicity and parental tobacco use between participants in the four use groups. Users of both substances appeared to be older, more likely to be female, of higher incomes, and Caucasian than users of either substance. Given the potential confounding influence of these differences, all analyses controlled for age and median academic performance. Grade in school was not controlled for, given its correspondence to age and ethnicity was not controlled for due to the difficulty in accounting for membership in multiple racial or ethnic groups. These data are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographic Characteristics by Alcohol-Tobacco Use Group

| Non-Users (n = 1120) | Users of Tobacco Only (n = 82) | Users of Alcohol Only (n = 974) | Users of Both (n = 557) | Significance Testing | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 53.2% female | 52.4% female | 53.4% female | 59.4% female | χ2 = 6.62, p = .085 |

| Mean Age | 14.97 ± 0.88 (SD) | 14.75 ± 1.04 (SD) | 14.61 ± 0.72 (SD) | 15.05 ± 0.97 (SD) | F = 21.71, p < .001 |

| Grade in School | χ2 = 71.83, p < .001 | ||||

| 9th | 34.1% | 30.5% | 23.1% | 21.0% | |

| 10th | 28.1% | 20.7% | 27.1% | 25.5% | |

| 11th | 25.9% | 31.7% | 29.3% | 31.8% | |

| 12th | 11.9% | 17.1% | 20.5% | 21.7% | |

| Median Grades | Mostly B’s | Mostly C’s | Mostly B’s | B’s and C’s | χ2 = 186.3, p < .001 |

| Ethnicity* | |||||

| Caucasian | 73.2% | 70.7% | 81.0% | 85.6% | χ2 = 41.8, p < .001 |

| African-American | 11.6% | 7.3% | 7.5% | 4.5% | χ2 = 26.7, p < .001 |

| Asian | 5.2% | 9.8% | 2.5% | 3.4% | χ2 = 17.7, p = .001 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 12.6% | 15.4% | 12.8% | 14.7% | χ2 = 1.80, p = .614 |

| Other Ethnicity | 14.3% | 19.5% | 12.8% | 11.7% | χ2 = 5.11, p = .164 |

| Familial Tobacco Use | 59.7% | 81.7% | 62.7% | 78.5% | χ2 = 70.4, p < .001 |

| Parental Use | 30.0% | 57.3% | 32.1% | 54.9% | χ2 = 125.2, p < .001 |

= Ethnicity categories are non-exclusive (i.e., students were asked to select as many ethnic categories as applied to them); totals do not add up to 100%

Impulsive Sensation Seeking, Alcohol Use and Concomitant Alcohol-Tobacco Use

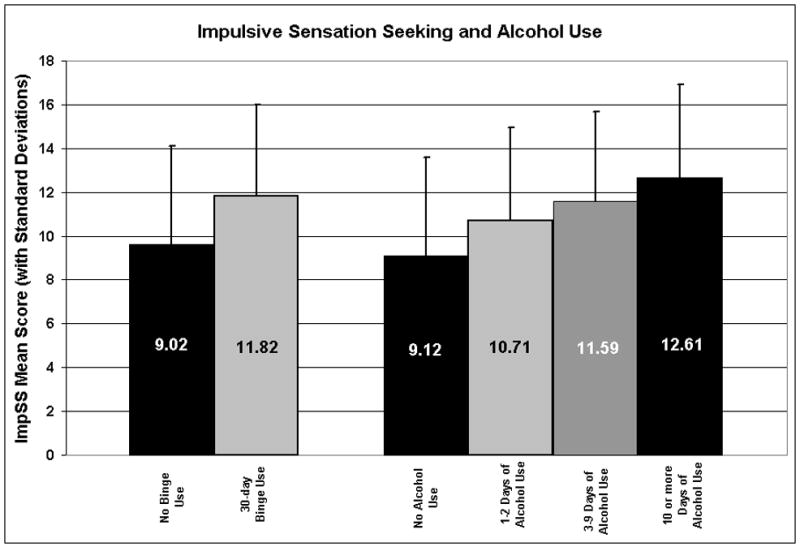

The omnibus GLM model examining the relationship of ImpSS scores and frequency of past month alcohol use indicated a significant association (F(3, 2729) = 76.32, p < .001, partial ε2 = .079). Bonferonni-corrected post hoc comparisons indicated that ImpSS scores increased in line with increasing frequency of alcohol consumption, with all groups significantly different (p = .01). Those who consumed alcohol on 10 or more days had the highest ImpSS scores (EMM = 12.61 ± 4.298), followed by those who consumed on three to nine days (EMM = 11.59 ± 4.070). Those who used alcohol on one or two days had the third-highest ImpSS scores (EMM = 10.71 ± 4.224), and adolescents who did not use had the lowest ImpSS scores (EMM = 9.12 ± 4.484). Adolescents who had consumed alcohol in a binge fashion (11.82 ± 4.172) had higher impulsive sensation seeking scores as compared to those who did not binge (9.61 ± 4.490; F(1, 2718) = 157.69, p < .001, partial ε2 = .056). These analyses are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Impulsive Sensation Seeking and Alcohol Use

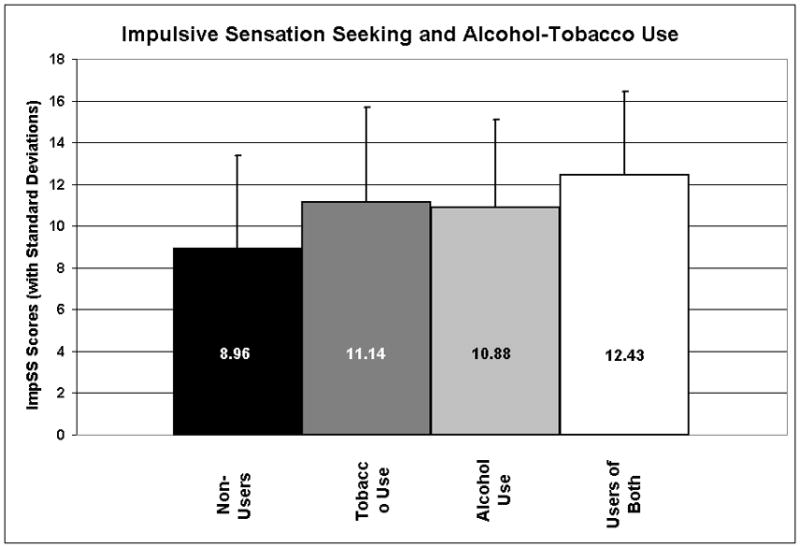

In examining concomitant alcohol and tobacco use, the omnibus GLM analysis revealed between-group differences in ImpSS scores (F(3, 2729) = 84.31, p < .001, partial ε2 = .087). Post hoc analyses indicated that two sets of significant differences existed: users of both alcohol and tobacco (12.43 ± 4.033) were more impulsive than users of only alcohol (10.88 ± 4.220), and all other groups had higher ImpSS scores than nonusers (8.96 ± 4.429; ps < .01). Users of alcohol only were not significantly different from users of tobacco only (11.14 ± 4.534; p = .825). Also, users of both did not significantly differ on ImpSS score from users of tobacco only (p = .062). These outcomes are summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Impulsive Sensation Seeking and Alcohol-Tobacco Use

History of Parental Alcohol Problems, Alcohol Use and Concomitant Alcohol-Tobacco Use

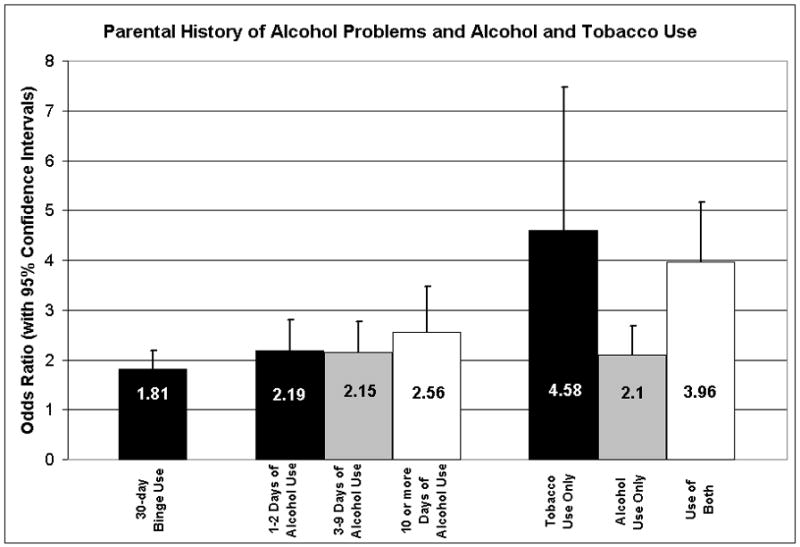

Logistic regression analyses indicated that a parental history of alcohol problems was associated with a greater likelihood of consuming alcohol on one or two days (OR = 2.19, 95% CI = 1.71–2.81), three to nine days (OR = 2.15, 95% CI = 1.67–2.76) and 10 days or more (OR = 2.56, 95% CI = 1.89–3.48) in the past month. Also, adolescents with a parental history of alcohol problems were more likely to have used alcohol in a binge fashion in the past month (OR = 1.81, 95% CI = 1.49–2.18).

For the analyses of concomitant alcohol and tobacco use, having a biological parent with an alcohol problem was associated significantly with increased likelihood of use of tobacco only (OR = 4.58, 95% CI = 2.80–7.48), use of alcohol only (OR = 2.10, 95% CI = 1.65–2.68) and use of both (OR = 3.96, 95% CI = 3.04–5.17) by adolescents, when compared to non-users. These data are captured in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Parental History of Alcohol Problems and Alcohol and Tobacco Use (Reference group is non-users or non-binge users)

Impulsive Sensation Seeking and History of Parental Alcohol Problems

Univariate GLM analyses were used to examine the relationship of the two independent variables: ImpSS scores and parental history of alcohol problems. As mentioned in the Methods section, establishing a significant relationship is needed to establish potential mediation between parental history of alcohol problems and current alcohol and tobacco use by impulsive sensation seeking. GLM analysis indicated that adolescents with a parental history of alcohol problems (11.35 ± 4.404) had higher ImpSS scores than adolescents with no parental history of alcohol problems (10.17 ± 4.511; F(1, 2731) = 31.83, p < .001, partial ε2 = .012).

Mediation Analyses

Having established the preconditions for potential mediation of the relationship between parental history of alcohol problems and current alcohol use and concomitant alcohol and tobacco use by impulsive sensation seeking, mediation was examined further. After controlling for the effects of ImpSS score, having a parental history of alcohol problems remained associated with a greater likelihood of consuming alcohol on one or two days (OR = 2.05, 95% CI = 1.59–2.64), three to nine days (OR = 1.94, 95% CI = 1.50–2.51) and 10 days or more (OR = 2.24, 95% CI = 1.63–3.07). Controlling for impulsive sensation seeking did not seem to impact the likelihood of consuming alcohol on one to two days (controlling for ImpSS: 2.05, not controlling: 2.19), three to nine days (controlling for ImpSS: 1.94, not controlling: 2.15), or 10 days or more (controlling for ImpSS: 2.24, not controlling: 2.56). Furthermore, the 95% confidence intervals for controlled and non-controlled analyses involving frequency of alcohol use overlapped, again suggesting no statistically significant differences.

In addition, having a biological parent with an alcohol problem was still significantly associated with binge use of alcohol in the past month after controlling for impulsive sensation seeking level (OR = 1.58, 95% CI = 1.29–1.92). The odds ratio for past month binge alcohol use (controlling for ImpSS: 1.58, not controlling: 1.81) was similar to the odds ratio when not controlling for impulsive sensation seeking. Despite the reduction in odds ratio value after controlling for ImpSS score, there was overlap in the 95% confidence intervals between the controlled and non-controlled odds ratio for past month binge alcohol use, suggesting no statistically significant difference.

Finally, having a biological parent with a history of an alcohol problem remained associated with past month concomitant alcohol-tobacco use after controlling for ImpSS score. Adolescents with a biological parent with an alcohol problem use history were more likely to have used tobacco only (OR = 4.24, 95%CI = 2.59–6.96), alcohol only (OR = 1.96, 95%CI = 1.53–2.52), or used both substances in the past month (OR = 3.57, 95%CI = 2.71–4.70), when compared to non-users. Controlling for ImpSS score only slightly altered the odds ratio for use of both alcohol and tobacco (controlling for ImpSS: 3.57, not controlling: 3.96), alcohol use only (controlling for ImpSS: 1.96, not controlling: 2.10), and tobacco use only (controlling for ImpSS: 4.24, not controlling: 4.58). As with the above analyses, the confidence intervals between the controlled and non-controlled analyses overlapped, suggesting no difference in outcomes. Data from the mediational analyses are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Parental History of Alcohol Problems, Impulsive Sensation Seeking and Alcohol and Tobacco Use

| Outcome | Non-Mediated (parental history only) | Mediated by ImpSS Score | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | |

| 1–2 days of Alcohol Use | 2.19 | 1.71–2.81 | 2.05 | 1.59–2.64 |

| 3–9 days of Alcohol Use | 2.15 | 1.67–2.76 | 1.94 | 1.50–2.51 |

| 10 or more days of Alcohol Use | 2.56 | 1.89–3.48 | 2.24 | 1.63–3.07 |

| 30-day Binge Use | 1.81 | 1.49–2.18 | 1.58 | 1.29–1.92 |

| Tobacco Use Only | 4.58 | 2.80–7.48 | 4.25 | 2.59–6.96 |

| Alcohol Use Only | 2.10 | 1.65–2.68 | 1.96 | 1.53–2.52 |

| Concomitant Use | 3.96 | 3.04–5.17 | 3.57 | 2.71–4.70 |

Discussion

These findings suggest that impulsive sensation seeking and a parental history of alcohol problems operate largely independently with respect to frequency of current alcohol use, current binge alcohol use, and concomitant alcohol-tobacco use. While both impulsive sensation seeking and parental history of alcohol problems were associated with the alcohol use variables and current alcohol-tobacco use, impulsive sensation seeking did not appear to mediate the relationship between parental history and current use. Overall, our results suggest that impulsivity and sensation seeking are not directly related to the psychosocial traits that transmit the risk for greater alcohol use and concomitant alcohol-tobacco use inherent in parental history of alcohol problems.

While the hypothesis that impulsive sensation seeking would mediate a portion of the relationship between parental history of alcohol problems and current alcohol use and current concomitant alcohol-tobacco use was not confirmed, the three other hypotheses appeared supported by these data. As expected, all alcohol use variables and concomitant alcohol-tobacco use were significantly associated with higher ImpSS scores. Also, parental history was associated with current use in a similar fashion, as those with a parental history were more likely to use alcohol more often, binge on alcohol, and use both alcohol and tobacco. Finally, adolescents with a parental history of alcohol problems had significantly higher impulsive sensation seeking scores than those who had no parental history.

It is important to note the limitations of the current study. As this study contained only one assessment point, true mediation could not be assessed. Also, many adolescents did not complete the survey, which left missing data for these analyses. Male participants, younger adolescents and those of non-Caucasian and non-Asian descent were less likely to have complete data, which could have influenced the results. This missing data could have introduced some degree of selection bias, which must be considered when interpreting the results. Much of the data in this report were categorical in nature, which limits the variability by collapsing continuous data. This was particularly true for the variables on any past 30-day cigarette use and any past 30-day binge alcohol use.

Another limitation was that parental history of alcohol problems was assessed only through a single question that relied on the adolescent’s perception of the alcohol use history of his or her parents. Despite evidence that this measure of parental alcohol problems has validity,40, 41 reliance on this measure could have resulted in misidentification of parental status because of a lack of awareness of problems by the adolescent or because of misinterpretation of the phrase “alcohol problem”. Thus, it is possible that some parents with a history of alcohol problems were not coded as such and that some parents were included in this group despite a lack of a genuine alcohol problem history, and interpretation of these findings must be tempered by recognition of this possibility. In addition, these data do not allow for analysis of the differential effects of biologically inherited traits and environmental influences as a result of having a parent with an alcohol problem history. Also, the use of a combined measure of impulsivity and sensation seeking (the ImpSS scale) may be less informative than separate measures of impulsivity and sensation seeking. Finally, there did appear to be some differences between the members of four alcohol-tobacco use groups on whether a parent or other family member smoked cigarettes. Because we did not capture lifetime parental or familial tobacco use, we could not control for this influence. It is possible that not controlling for familial tobacco use influenced the results, particularly for analyses involving concomitant alcohol and tobacco use. Future investigations can expand on our findings by addressing some of these limitations to further evaluate the relationships of impulsivity, sensation seeking, parental alcohol problems and current alcohol and tobacco use.

These findings suggest several important directions for future research. First, these results need to be replicated, preferably in a longitudinal sample where true mediation can be assessed (as opposed to this cross-sectional sample). If these results are independently supported, then it would be important to establish the relative contributions of impulsive sensation seeking and parental history, perhaps via structural equation modeling. This would also allow for the inclusion of other relevant variables (e.g., externalizing psychopathology, level of response to alcohol) and would illustrate both the paths through which alcohol use and concomitant alcohol-tobacco use develop in adolescents and the relative strengths of associations. Second, the literature would benefit from further exploration of which neurocognitive or psychosocial traits associated with parental history of alcohol problems serve as the mechanisms of the risk imparted by parental history. While there is a clear relationship between parental history and greater likelihood of later alcohol use, later problem alcohol use and later concurrent alcohol-tobacco use, it is unclear what traits actually transmit the risk in this relationship.

Conclusions

In all, these findings indicate that parental history of alcohol problems and impulsive sensation seeking operate largely independently in adolescents to increase the likelihood of more frequent alcohol consumption, current binge alcohol use, and concomitant alcohol and tobacco use. These findings suggest that psychosocial and other neurocognitive traits besides impulsivity and sensation seeking conferred by a parental history of alcohol problems influence alcohol and tobacco use in adolescents. Furthermore, it is important to assess both impulsive sensation seeking levels and presence or absence of a parental history of alcohol problems in adolescents, especially those otherwise at risk for alcohol use. It is hoped that future investigations will identify the specific neurocognitive or psychosocial traits associated with a parental history of alcohol problems that serve as the mechanisms by which parental history confers risk for elevated alcohol use and use this information to advance prevention and treatment strategies for adolescent alcohol and tobacco use.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this manuscript was supported by NIH grants P50 AA15632, P50 DA09421, P50 DA016556, RL1 AA017539, R01 DA019039, and T32 DA07238. Funding was also provided by the State of Connecticut.

Sources of Support

Preparation of this manuscript was supported by NIH grants P50 AA15632, P50 DA09421, P50 DA016556, RL1 AA017539, R01 DA019039, and T32 DA07238. Funding was also provided by the State of Connecticut.

References

- 1.Moeller FG, Barratt ES, Dougherty DM, et al. Psychiatric aspects of impulsivity. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1783–1793. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zuckerman M. Sensation Seeking And Risky Behavior. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yanovitzky I. Sensation seeking and alcohol use by college students: examining multiple pathways of effects. J Health Commun. 2006;11:269–280. doi: 10.1080/10810730600613856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D’Alessio M, Baiocco R, Laghi F. The problem of binge drinking among Italian university students: a preliminary investigation. Addict Behav. 2006;31:2328–2333. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robbins RN, Bryan A. Relationships Between Future Orientation, Impulsive Sensation Seeking, and Risk Behavior Among Adjudicated Adolescents. J Adolesc Res. 2004;19:428–445. doi: 10.1177/0743558403258860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simons JS, Carey KB, Gaher RM. Lability and impulsivity synergistically increase risk for alcohol-related problems. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2004;30:685–694. doi: 10.1081/ada-200032338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kreek MJ, Nielsen DA, Butelman ER, et al. Genetic influences on impulsivity, risk taking, stress responsivity and vulnerability to drug abuse and addiction. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1450–1457. doi: 10.1038/nn1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finn PR. Motivation, working memory, and decision making: a cognitive-motivational theory of personality vulnerability to alcoholism. Behav Cogn Neurosci Rev. 2002;1:183–205. doi: 10.1177/1534582302001003001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beyers JM, Toumbourou JW, Catalano RF, et al. A cross-national comparison of risk and protective factors for adolescent substance use: the United States and Australia. J Adolesc Health. 2004;35:3–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crawford AM, Pentz MA, Chou CP, et al. Parallel developmental trajectories of sensation seeking and regular substance use in adolescents. Psychol Addict Behav. 2003;17:179–192. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.17.3.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conrod PJ, Castellanos N, Mackie C. Personality-targeted interventions delay the growth of adolescent drinking and binge drinking. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49:181–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Magid V, MacLean MG, Colder CR. Differentiating between sensation seeking and impulsivity through their mediated relations with alcohol use and problems. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2046–2061. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kahler CW, Read JP, Wood MD, et al. Social environmental selection as a mediator of gender, ethnic, and personality effects on college student drinking. Psychol Addict Behav. 2003;17:226–234. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.17.3.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hittner JB, Swickert R. Sensation seeking and alcohol use: a meta-analytic review. Addict Behav. 2006;31:1383–1401. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soloff PH, Lynch KG, Moss HB. Serotonin, impulsivity, and alcohol use disorders in the older adolescent: a psychobiological study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:1609–1619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mackillop J, Mattson RE, Anderson Mackillop EJ, et al. Multidimensional assessment of impulsivity in undergraduate hazardous drinkers and controls. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2007;68:785–788. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goudriaan AE, Grekin ER, Sher KJ. Decision making and binge drinking: a longitudinal study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:928–938. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00378.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dougherty DM, Mathias CW, Tester ML, et al. Age at first drink relates to behavioral measures of impulsivity: the immediate and delayed memory tasks. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:408–414. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000117834.53719.a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grano N, Virtanen M, Vahtera J, et al. Impulsivity as a predictor of smoking and alcohol consumption. Personality and Individual Differences. 2004;37:1693–1700. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Conway KP, Swendsen JD, Merikangas KR. Alcohol expectancies, alcohol consumption, and problem drinking: the moderating role of family history. Addict Behav. 2003;28:823–836. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00265-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warner LA, White HR, Johnson V. Alcohol initiation experiences and family history of alcoholism as predictors of problem-drinking trajectories. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2007;68:56–65. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Volicer L, Volicer BJ, D’Angelo N. Relationship of family history of alcoholism to patterns of drinking and physical dependence in male alcoholics. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1984;13:215–223. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(84)90062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng AT, Gau SF, Chen TH, et al. A 4-year longitudinal study on risk factors for alcoholism. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:184–191. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grant BF. The impact of a family history of alcoholism on the relationship between age at onset of alcohol use and DSM-IV alcohol dependence: results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. Alcohol Health Res World. 1998;22:144–147. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sher KJ. Psychological characteristics of children of alcoholics. Alcohol Health Res World. 1997;21:247–254. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jackson KM, Sher KJ, Wood PK. Prospective analysis of comorbidity: tobacco and alcohol use disorders. J Abnorm Psychol. 2000;109:679–694. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.109.4.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jackson KM, Sher KJ, Wood PK. Trajectories of concurrent substance use disorders: a developmental, typological approach to comorbidity. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:902–913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nurnberger JI, Jr, Wiegand R, Bucholz K, et al. A family study of alcohol dependence: coaggregation of multiple disorders in relatives of alcohol-dependent probands. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:1246–1256. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.12.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Finn PR, Earleywine M, Pihl RO. Sensation seeking, stress reactivity, and alcohol dampening discriminate the density of a family history of alcoholism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1992;16:585–590. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1992.tb01421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ratsma JE, van der Stelt O, Schoffelmeer AN, et al. P3 event-related potential, dopamine D2 receptor A1 allele, and sensation-seeking in adult children of alcoholics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:960–967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schweinsburg AD, Paulus MP, Barlett VC, et al. An FMRI study of response inhibition in youths with a family history of alcoholism. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1021:391–394. doi: 10.1196/annals.1308.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elkins IJ, McGue M, Malone S, et al. The effect of parental alcohol and drug disorders on adolescent personality. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:670–676. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.4.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Swendsen JD, Conway KP, Rounsaville BJ, et al. Are personality traits familial risk factors for substance use disorders? Results of a controlled family study. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1760–1766. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.10.1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schuckit MA, Smith TL, Pierson J, et al. Patterns and correlates of drinking in offspring from the San Diego Prospective Study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:1681–1691. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grucza RA, Robert Cloninger C, Bucholz KK, et al. Novelty seeking as a moderator of familial risk for alcohol dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:1176–1183. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zuckerman M, Kuhlman DM, Joireman J, et al. A Comparison of 3 Structural Models for Personality - the Big 3, the Big 5, and the Alternative 5. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;65:757–768. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmid B, Hohm E, Blomeyer D, et al. Concurrent alcohol and tobacco use during early adolescence characterizes a group at risk. Alcohol Alcohol. 2007;42:219–225. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agm024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Orlando M, Tucker JS, Ellickson PL, et al. Concurrent use of alcohol and cigarettes from adolescence to young adulthood: an examination of developmental trajectories and outcomes. Subst Use Misuse. 2005;40:1051–1069. doi: 10.1081/JA-200030789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Best D, Rawaf S, Rowley J, et al. Drinking and smoking as concurrent predictors of illicit drug use and positive drug attitudes in adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;60:319–321. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Slutske WS, Heath AC, Madden PA, et al. Reliability and reporting biases for perceived parental history of alcohol-related problems: agreement between twins and differences between discordant pairs. J Stud Alcohol. 1996;57:387–395. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cuijpers P, Smit F. Assessing parental alcoholism: a comparison of the family history research diagnostic criteria versus a single-question method. Addict Behav. 2001;26:741–748. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00155-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]