Abstract

Hybrid hybridomas (quadromas) are derived by fusing at least two hybridomas, each producing a different antibody of predefined specificity. The resulting cell secretes not only the immunoglobulins of both parents but also hybrid molecules manifesting the binding characteristics of the individual fusion partners. Purification of the desired bispecific immunoprobe with high specific activity from a mixture of bispecific and monospecific monoclonal antibodies requires special strategies. Using a dual, sequential affinity chromatography (Protein-G chromatography followed by m-aminophenyleboronic acid agarose column), we have purified bispecific monoclonal antibodies (BsMAb) as a preformed HRPO (Horseradish Peroxidase) complex (BsMAb–HRPO). The quadroma culture supernatant was initially processed on a Protein-G column to isolate all the species of immunoglobulins. This pre-enriched fraction was subsequently passed through the aminophenyleboronic acid column super saturated with HRPO. The column matrix has the ability to bind to proteins such as HRPO with vicinal diols. The enzyme loaded column captures the desired bispecific anti-SARS-CoV × anti-HRPO species with the elimination of the monospecific anti-SARS-CoV MAb to result in a high specific activity diagnostic probe. The presence of anti-HRPO MAb is an acceptable impurity as it will not bind to the target SARS-CoV NP antigen and will get washed out during the ELISA procedure.

Keywords: SARS-CoV, Bispecific monoclonal antibodies, m-Aminophenylboronic acid

1. Introduction

Bispecific monoclonal antibodies (BsMAb) are unique macromolecules functioning as cross-linkers with two different predetermined binding specificities [1]. These antibodies have unique applications in immunodiagnostics [2], [3] and immunotherapy [4], [5]. Since the report of development of bifunctional antibodies from hybrid hybridomas [6], increased attention has been focused on these cross-linking immunoprobes incorporating two different paratopes in a single antibody molecule. Our laboratory has extensively adopted the hybrid hybridoma method [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13] of generating different BsMAbs for diagnostic applications. Antibodies with enzyme tags are used extensively in biochemical and immunochemical applications. Horseradish peroxidise (HRPO) and alkaline phosphatase (AP) are the most widely used enzymes among several described in the literature. Previous work in our laboratory has resulted in the development of several BsMAbs with anti-tumor antigen specificity in one arm and anti-enzyme specificity in, the other arm [8], [9], [10], [11], [14]. Our laboratory has previously purified alkaline phosphatase-labelled BsMAbs using Mimetic Red 3 [10] matrix and the purification of the uncomplexed BsMAb on an HRPO-agarose column [3]. The challenge of obtaining bispecific immunoprobes with high specific activity and purity was circumvented by using benzhydroxamic acid agarose to purify the antibodies [15] tagged with HRPO as a preformed immune complex [15], [16]. Benzhydroxamic acid agarose (BHA-agarose) has been reported to bind at the active site of HRPO [17]. Unfortunately, due to the discontinuation of BHA-agarose production by the vendor, we attempted to develop an alternative affinity chromatography method for the purification of BsMAb with one arm specific to HRPO and the other arm specific to Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome's (SARS-CoV) nucleoprotein (NP) antigen, using novel boronate affinity matrix called m-aminophenylboronic acid agarose (APBA-agarose). Immobilized phenylboronic acid has been utilized selectively to retain carbohydrates, catecholamines, prostaglandins, ribonucleosides, and steroids [18], [19], [20]. Boronic acid can form reversible bonds with 1,2- or 1,3-diols to generate five or six membered cyclic complexes under mild conditions [21], [22]. Immobilized boronic acid derivatives have been reported to form reversible complexes with diol-containing compounds such as nucleotides [23] nucleosides [24], nucleic acids [25] and carbohydrates [26]. Use of immobilized phenylboronic acid derivatives to separate diol-containing nucleotide was first suggested nearly four decades ago [24]. The ability of boron to form specific complexes with cis-diols has also been explored to separate glycoproteins [18]. The utilization of the carbohydrate moiety as the binding site has an advantage since these regions are generally not involved with their biological activities [27]. Therefore, many glycoproteins, including hormones [28], antibodies [29] and enzymes such as horseradish peroxidase, lactamases, hexokinase, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase [30], [31], [32], retain most of their biological activities even when their carbohydrate regions are modified or altered. We speculated that APBA-agarose presaturated with HRPO could purify the BsMAb as HRPO-labelled BsMAb complex. The advantages of BsMAb over monospecific MAb are (1) two non identical paratopes incorporated in a single antibody for efficient cross linking avoiding chemical conjugation, (2) reduces the assay format by one step in turn reducing the time for the assay, (3) and very low signal to noise ratio due to molecular uniformity of BsMAb, (4) the bispecific design can generate the theoretical limit of tracer specific activity with every molecule bound to HRPO, (5) the quadromas can generate abundant BsMAb thus providing the detecting antibody in the total absence of random crosslinking of the enzyme. Here we describe the alternative method for purification of HRPO-labelled BsMAb for application in immunoassays.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

Horseradish peroxidase (Type VI), m-aminophenylboronic acid agarose (binding capacity to HRPO: 8–14 mg/ml of the gel), Protein-G sepharose and Goat anti-mouse IgG HRPO conjugated antibodies, were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Dialysis tubing (12,000 MW cut off) was obtained from BioDesign Inc. (Carmel, NY, USA). ELISA plates were from NUNC and TMB (3,3’,5,5”-tetramethylbenzidine) substrate was obtained from KPL scientific.

2.2. Monoclonal antibodies and cell lines

YP4 is a rat hybridoma secreting (IgG2a) monospecific anti-horseradish peroxidase antibodies obtained from Late Dr. C. Milstein, MRC laboratory of Molecular Biology, Cambridge, UK. The SARS-CoV Nucleocapsid Protein (NP) hybridoma secreting anti-NP monoclonal antibody (IgG1 class) was developed in our laboratory (manuscript in preparation). P143 is a well characterized, BsMAb secreting quadroma developed in our laboratory which binds to HRPO and Nucleocapsid Protein of SARS-CoV in one molecule (manuscript in preparation).

2.3. BsMAb Enzyme Linked Immuno Sorbant Assay (ELISA)

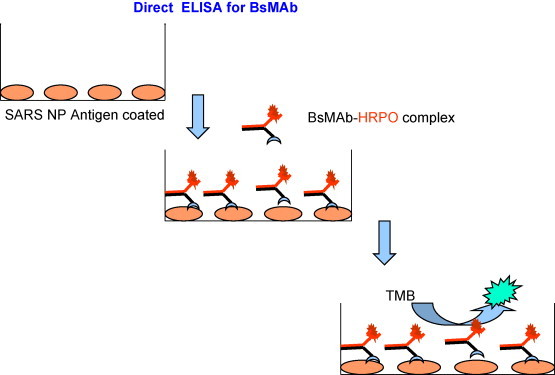

ELISA to detect the P143 bispecific antibodiess (BsMAb) and or HRPO-labeled P143 BsMAb: The plate was coated with 100 μl of SARS-CoV NP antigen (5 μg/ml) and incubated overnight (16 h) at 4 °C. The plate was washed three times with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T) and was incubated with 3% BSA–PBS for 1 h at 37 °C to block the non-specific binding sites. The plate was washed and 100 μl of the various dilutions of the BsMAb crude culture supernatant or Protein-G purified fractions of the culture supernatant were added to the wells and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. The plate was washed and 100 μl of 10 μg/ml HRPO (in 1% BSA–PBS) was added for 1 h at 37 °C. When HRPO-labeled BsMAb was assessed, the step for addition of HRPO was eliminated (Fig. 1 ). The color was developed using 3,3’,5,5”-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate.

Fig. 1.

Direct ELISA format for BsMAb activity. This format was used to detect the presence of HRPO-labelled BsMAb from the APBA-agarose column. The plate was coated with SARS-CoV NP antigen (100 μl of 5 μg/ml) overnight (16 h) at 4 °C and was incubated with 3% BSA–PBS for 1 h at 37 °C to block the non-specific binding sites. A 100 μl aliquot of the various dilutions of the BsMAb crude culture supernatant or Protein-G purified fractions of the culture supernatant were added to the wells and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. The plate was washed with PBS and 100 μl of 10 μg/ml HRPO (in 1% BSA–PBS) was added for 1 h at 37 °C. When HRPO-labelled BsMAb was assessed, the step for addition of HRPO was eliminated. The color was developed using TMB substrate.

2.4. Affinity purification of HRPO with the m-aminophenylboronic acid agarose column

As an initial experiment crude HRPO (Type VI, Sigma Inc. USA) was dissolved in 50 mM potassium phosphate (KH2PO4/K2HPO4, pH 7.4) buffer to a final concentration of 2 mg/ml (5 ml) and loaded on to a column containing 2 ml pre-equilibrated APBA-agarose matrix. The column flow rate was 18 ml/h. The column was washed with 10 column volumes of potassium phosphate buffer pH 7.4 and eluted with phosphate buffer containing 0.1 M sorbitol. Unbound and eluted fractions of 0.5 ml size were collected and analyzed.

2.5. Affinity purification of HRPO labelled bispecific antibodies (BsMAb)

The purification of BsMAbs complexed with HRPO was performed in two steps using a combination of affinity chromatography. In the first step, all the immunoglobulins (both parental monospecific and bispecific monoclonal antibodies) were purified from the supernatant by Protein-G purification and these immunoglobulins were then passed through HRPO saturated (15 mg HRPO/ml of the gel) m-aminophenylboronic acid agarose column. The eluate is expected to be enriched with BsMAb and monospecific anti-HRPO antibodies both complexed with HRPO. The detailed procedure is given below.

2.5.1. Protein-G purification

Supernatant of a 1 L quadroma culture was centrifuged at 4 ̊C at 8000 rpm for 30 min to remove the cells. The crude immunoglobulin supernatant was loaded on to a 10 ml bed volume of Protein-G sepharose column equilibrated with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) pH 7.4. The column was washed until the absorbance at 280 nm of the wash reached zero. The bound immunoglobulins were eluted by 0.1 M glycine, pH 2.8 and the fractions were neutralized with 1 M Tris pH 9.0. The eluted fractions were read at 280 nm. The fractions constituting a peak were pooled and dialyzed against PBS. It was then tested for BsMAb activity by ELISA. The pooled eluate would contain a mixture of anti-NP and anti-HRPO MAbs, and BsMAbs capable of binding to both NP and HRPO antigen. The following procedure will allow anti-HRPO and BsMAb to bind to HRPO already bound to APBA-agarose column which will then get eluted.

2.5.2. Saturation of APBA-agarose with HRPO

The ability of APBA-agarose binding to the carbohydrate moiety of HRPO is exploited for purification of our BsMAb. The APBA-agarose was washed three times with potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. The glycoprotein binding sites of APBA-agarose were saturated with 15 mg of HRPO per ml of bed volume. HRPO was mixed with 2 ml of APBA-agarose and incubated at 4 °C overnight with continuous gentle mixing. The mixture was washed with potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 to remove the unbound HRPO. A 5 ml size column was packed with the HRPO saturated APBA-agarose (HRPO-APBA-agarose matrix) and again equilibrated with potassium phosphate buffer. A mixture of both MAbs and BsMAb obtained from Protein-G purification was then loaded on to the HRPO-APBA-agarose matrix. The column flow rate was 18 ml/h. The unbound eluate is expected to contain the monospecific anti-SARS-CoV antibodies. After loading, the column was washed with 25 column volumes of potassium phosphate buffer and eluted with potassium phosphate buffer containing 0.1 M sorbitol. The unbound and eluted fractions of 1 ml size were collected separately and analyzed for the BsMAb activity. The positive fractions were then pooled and dialyzed against phosphate buffer. The protein was estimated by Biorad protein assay.

3. Results

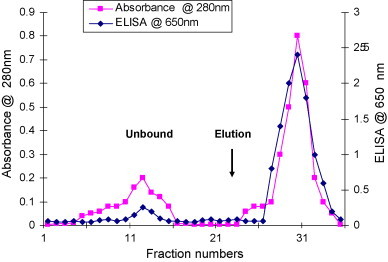

3.1. Affinity purification of HRPO

Initially HRPO was purified alone, in order to test the APBA-agarose column and establish the affinity purification method of peroxidase as described previously [18], [19]. A 3 ml column was packed with 2 ml of gel. The column was first washed with potassium phosphate buffer pH 7.4 (equilibration buffer). Approximately 10 mg of peroxidase was dissolved in equilibration buffer and loaded on the APBA-agarose column. The column was washed subsequently until the absorbance returned to the baseline. Elution was accomplished using 0.1 M sorbitol in equilibration buffer. The absorbance of each collected fraction was recorded and each fraction was tested in an ELISA plate coated with anti-HRPO antibodies in order to assay the activity of peroxidase in each fraction. Protein absorbance was seen in both unbound and eluted fractions. The HRPO activity was much higher in the eluted fraction when compared with the unbound fractions (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Binding of crude HRPO (VI) on m-aminophenyleboronic acid agarose column. Crude HRPO (Type VI, Sigma Inc. USA) was dissolved in 50 mM potassium phosphate (KH2PO4/K2HPO4, pH 7.4) buffer to a final concentration of 2 mg/ml (5 ml) and loaded on to a column containing 2 ml pre-equilibrated APBA matrix. The column flow rate was 18 ml/h. The column was washed with 10 column volumes of potassium phosphate buffer pH 7.4 and eluted with phosphate buffer containing 0.1 M sorbitol. Unbound and eluted fractions of 0.5 ml size were collected and analyzed.

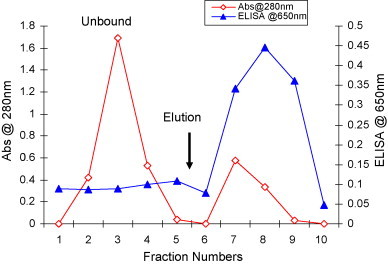

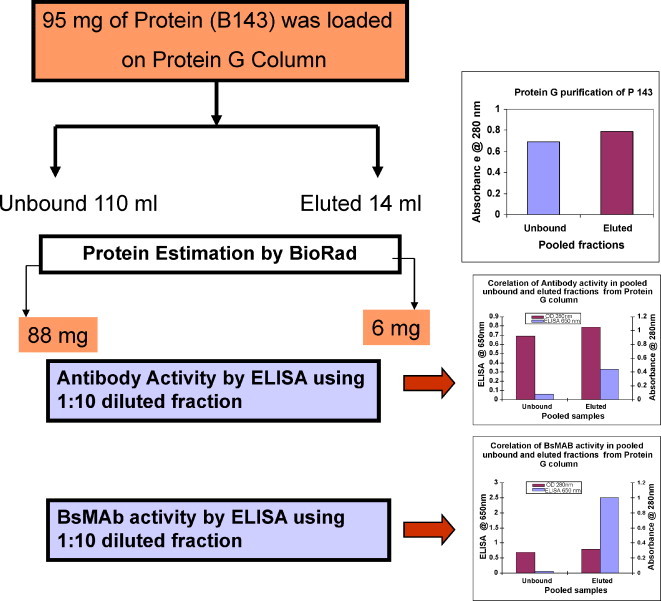

3.2. Affinity purification of immunoglobulins on Protein-G sepharose column

The unbound and eluted fractions of P143 BsMAb were subjected to ELISA for activity of BsMAb activity in an NP antigen coated plate. The chromatographic profile of the Protein-G purified P143 is shown in Fig. 3 . It was observed that a large amount of protein that did not bind (unbound) to the column showed negligible peroxidase activity but higher protein amount as compared to the eluted fractions which showed a small amount of protein but very high peroxidase activity, when the fractions were subjected to the ELISA to detect HRPO-labelled BsMAb. The eluted fractions with high peroxidase activity were pooled and dialyzed against PBS. The yield of purified total IgG was 6 mg as estimated by BioRad assay.

Fig. 3.

Purification profile of BsMab culture supernatant on Protein-G column and BsMAb activity in corresponding fractions. One liter of the quadroma supernatant was processed on a 5 ml Protein-G column and eluted with 0.1 M glycine buffer pH 2.8 to obtain total immunoglobulin. Each fraction was tested for protein and BsMAb activity.

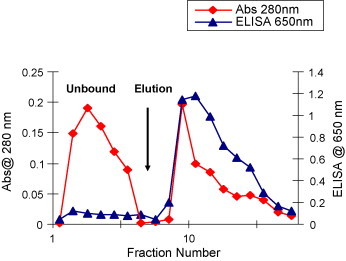

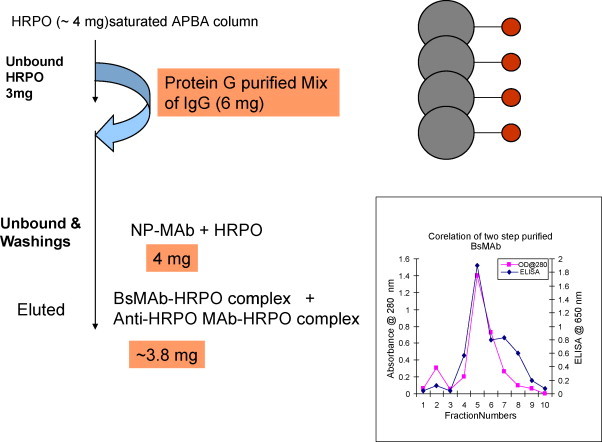

3.3. Affinity co-purification of P143 BsMAbs (anti-SARS-CoV NP × anti-HRPO)

The Protein-G purified P143 antibodies (6 mg, mixture of both parental monospecific anti-HRPO, anti-SARS-CoV and bispecific anti-SARS-CoV × anti-HRPO antibodies) were then loaded on HRPO saturated APBA-agarose column. The purification profile revealed the presence of protein in both unbound and eluted fractions. The analysis of these fractions (both unbound and eluted) by ELISA for HRPO bound antibodies revealed very little or no HRPO activity in unbound fractions, however, a very high HRPO activity was seen in eluted fractions (Fig. 4 ). The A 280 absorbance peak corresponded with single peak of peroxidase activity in eluted fractions. The final yield of purified bispecific antibody–HRPO complex was 3.8 mg. The ELISA values showed that co-purification of the BsMAb–HRPO complex was in the eluted fractions constituting the second peak.

Fig. 4.

Purification of pooled Protein-G eluate on APBA column. BsMAb activity in unbound and eluted fractions was tested by direct ELISA on SARS-CoV NP antigen coated plates. Pooled fractions were dialyzed against 50 mM potassium phosphate (KH2PO4/K2HPO4, pH 7.4) buffer and loaded on to a column containing 2 ml pre-equilibrated APBA-agarose matrix. The column flow rate was 18 ml/h. The column was washed with 10 column volumes of potassium phosphate buffer pH 7.4 and eluted with phosphate buffer containing 0.1 M sorbitol. Unbound and eluted fractions of 0.5 ml size were collected and analyzed.

3.4. SDS-PAGE analysis of crude P143, purified P143, HRPO, and commercial antibodies

An SDS-PAGE analysis was performed to observe the nature of the various fractions. The gel was stained with Coomassie blue to observe proteins. All the samples, including the crude mix of antibodies, Protein-G purified and APBA-agarose purified antibodies were analyzed on SDS-PAGE. A heavy (∼50 kDa Mw) and two light chain bands (∼27 kDa Mw) characteristic of bispecific species [6] were observed (data omitted). A summary of flow chart of yield of antibody at each step is shown in Fig. 5, Fig. 6 .

Fig. 5.

Flow chart summary of Protein-G purification steps corelating with the yield and activity of antibody.

Fig. 6.

Flow chart summary of APBA-agarose purified antibody yield and its activity.

4. Discussion

Monoclonal antibodies (MAb) represent one of the fastest growing areas of new diagnostic and drug development within the pharmaceutical industry. A number of applications using MAb involve chemical manipulation of the antibody to create covalent immunoconjugates with enzymes, drugs, etc. Refinement in chemical conjugation methods, employing heterobifunctional cross-linkers, has mitigated the problem of random conjugations but not entirely eliminated them [33]. BsMAb with intrinsic binding sites to any two antigens has the capability to form uniform, homogenous, and reproducible high specific activity immunoconjugates with one or two entities in predetermined order [2]. The cross-linking ability of BsMAb to any two defined antigens makes them a better alternative to the widely used chemical covalent cross-linking methods, at least in major areas of applied immunology; immunoassays, immunohistochemistry and immunotargeting. A wide range of potential applications employing these probes have been described in literature [7], [11], [12], [13], [16]. One of the major limitations for use of BsMAb produced by hybrid hybridoma is the production of parental monospecific antibodies along with BsMAb. Hence the purification of BsMAb is essential. Our laboratory has exploited the property benzhydroxamic acid agarose (BHA) binding to peroxidase for purifying BsMAb with covalently or non-covalently bound HRPO. Due to the commercial non-availability of BHA (UpFront Chromatography, Copenhagan, Denmark), we attempted to develop an alternative affinity chromatography method for the purification of BsMAb with one arm specific to HRPO and the other arm specific to SARS-CoV nucleoprotein antigen, using a novel boronate affinity gel available as m-aminophenylboronic acid agarose. Because of binding of HRPO to ABPA, purification of BsMAb inevitably yields antibodies which are bound to HRPO and have higher specific activity. It is to be emphasized that when purifying BsMAbs with either BHA or APBA, free HRPO and monospecific anti-HRPO also gets co-purified. However, the presence of monospecific anti-HRPO antibodies complexed with HRPO is not an issue because this will not be able to bind the target NP antigen coated plates and thus will be washed out in the ELISA. The elution conditions of the affinity chromatography are very mild and potassium phosphate buffer containing 0.1 M sorbitol is used which is of routine use in all biological applications. This procedure can be adopted for affinity purification of any protein attached to peroxidase such as chemical conjugates of antibodies. The purified HRPO/anti-HRPO bispecific antibody immune complex could be directly used for in vitro diagnostics or immunohistology, wherein the second arm of the bispecific antibody binds specifically to a target, such as SARS-CoV antigen, or a tumor marker. There is no common purification method for BsMAb. A combination of Protein-A, ion-exchange chromatography, size exclusion chromatographic techniques has been used to purify BsMAb from a mixture of mono and bispecific species. These non-specific methods are subjected to trial and error [34] and can be time consuming. The use of benzhydroxamic acid agarose was an ideal method [16] to quickly and easily purify BsMAb labelled with HRPO.

5. Conclusion

We have developed a novel dual sequential affinity procedure on m-aminophenylboronic acid agarose for a convenient alternative method for purification of BsMAb or a protein conjugated to peroxidase. Using 1 L of BsMAb culture supernatant, we were able to obtain 3.8 mg of high specific activity HRPO-BsMAb complex along with HRPO–anti-HRPO antibody complex (Fig. 5, Fig. 6) which is enough for 40 ELISA plates or 40,000 wells.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by a research grant (5U01AI061233-02) from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, part of the National Institutes of Health, USA.

References

- 1.Milstein C., Cuello A.C. Nature. 1983;305:537. doi: 10.1038/305537a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suresh M.R., Cuello A.C., Milstein C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1986;83:7989. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.20.7989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cao Y., Christian S., Suresh M.R. J. Immunol. Methods. 1998;220:85. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(98)00154-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nolan O., O’Kennedy R. Int. J. Clin. Lab. Res. 1992;22:21. doi: 10.1007/BF02591389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warnaar S.O., De Paus V., Lardenoije R., Machielse B.N., De Graaf J., Bregonje M., Van Haarlem H. Hybridoma. 1994;13:519. doi: 10.1089/hyb.1994.13.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suresh M.R., Cuello A.C., Milstein C. Methods Enzymol. 1986;121:210. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(86)21019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhatnagar P.K., Suresh M.R. J. Tumor Marker Oncol. 2000;15:253. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kreutz F.T., Wishart D.S., Suresh M.R. J. Chromatogr. B Biomed. Sci. Appl. 1998;714:161. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(98)00180-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kreutz F.T., Suresh M.R. Clin. Chem. 1997;43:649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu D., Leveugle B., Kreutz F.T., Suresh M.R. J. Chromatogr. B Biomed. Sci. Appl. 1998;706:217. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(97)00441-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cao Y., Suresh M.R. Bioconjug. Chem. 1998;9:635. doi: 10.1021/bc980044l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Das D., Suresh M.R. Methods Mol. Med. 2005;109:329. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-862-5:329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kreutz F.T., Suresh M.R. J. Tumor Marker Oncol. 1995;10:45. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cao Y., Suresh M.R. J. Drug Target. 2000;8:257. doi: 10.3109/10611860008997904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang X.L., Peppler M.S., Irvin R.T., Suresh M.R. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 2004;11:752. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.11.4.752-757.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Husereau D.R., Suresh M.R. J. Immunol. Methods. 2001;249:33. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(00)00277-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Ropp J.S., Mandal P.K., La Mar G.N. Biochemistry. 1999;38:1077. doi: 10.1021/bi982125a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu X.C., Scouten W.H. J. Mol. Recognit. 1996;9:462. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1352(199634/12)9:5/6<462::aid-jmr283>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu X.C., Scouten W.H. Methods Mol. Biol. 2000;147:119. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-261-2_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu S., Wollenberger U., Halamek J., Leupold E., Stocklein W., Warsinke A., Scheller F.W. Chemistry. 2005;11:4239. doi: 10.1002/chem.200400827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soundararajan S., Badawi M., Kohlrust C.M., Hageman J.H. Anal. Biochem. 1989;178:125. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90367-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strawbridge S., Green S.J., Tucker J.H.R. Chem. Commun. 2000:2393. doi: 10.1039/b510513g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenberg M., Wiebers J.L., Gilham P.T. Biochemistry. 1972;11:3623. doi: 10.1021/bi00769a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weith H.L., Wiebers J.L., Gilham P.T. Biochemistry. 1970;9:4396. doi: 10.1021/bi00824a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pace B., Pace N.R. Anal. Biochem. 1980;107:128. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(80)90502-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yurkevich A.M., Kolodkina I.I., Ivanova E.A., Pichuzhkina E.I. Carbohydr. Res. 1975;43:215. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kas J., Sajdok J., Turkova J., Petkov L. Proc. Eur. Congr. Biotechnol. 1990;2:778. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ingham K.C., Brew S.A. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1981;670:181. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(81)90007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Shannessy D.J., Voorstad P.J., Quarles R.H. Anal. Biochem. 1987;163:204. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90114-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsang V.C., Hancock K., Maddison S.E. J. Immunol. Methods. 1984;70:91. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(84)90393-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams D.G. J. Immunol. Methods. 1984;72:261. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(84)90454-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cartwright S.J., Waley S.G. Biochem. J. 1984;221:505. doi: 10.1042/bj2210505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hermanson G.T. Academic Press; New York: 1996. Bioconjugate Techniques. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gupta S., Suresh M. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods. 2002;51:203. doi: 10.1016/s0165-022x(01)00231-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]