Abstract

AIM: To explore the efficacy and safety of herbal medicines (HM) in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

METHODS: A computer-based as well as manual literature search was performed. We reviewed randomized controlled trials on the treatment of IBS with and without HM.

RESULTS: A total of 22 studies with 25 HMs met the inclusion criteria. Four of these studies were of good quality, while the remaining 18 studies involving 17 Chinese herbal medicine (CHM) formulas were of poor quality. Eight of these reports using 9 HMs showed global improvement of IBS symptoms, 4 studies with 3 HMs were efficacious in diarrhea-predominant IBS, and 2 studies with 2 HMs showed improvement in constipation-predominant IBS. Out of a total of 1279 patients, 15 adverse events in 47 subjects were reported with HM. No serious adverse events or abnormal laboratory tests were observed. The incidence of the adverse events was low (2.97%; 95% CI: 2.04%-3.90%).

CONCLUSION: Herbal medicines have therapeutic benefit in IBS, and adverse events are seldom reported in literature. Nevertheless, herbal medicines should be used with caution. It is necessary to conduct rigorous, well-designed clinical trials to evaluate their effectiveness and safety in the treatment of IBS.

Keywords: Irritable bowel syndrome, Herbal medicine, Systematic review

INTRODUCTION

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is associated with a variable combination of chronic or recurrent symptoms such as abdominal pain, bloating, constipation and diarrhea. There is generally no structural or biochemical abnormality detected by conventional laboratory tests. IBS is one of the most common functional gastrointestinal disorders accounting for 3% of all primary consultations[1]. In western countries, the prevalence of IBS is around 10%, depending upon the definition used[2]. Moreover, there is increasing prevalence of IBS in the newly developed Asian countries[3]. The potential etiological factors include stress, anxiety, visceral hypersensitivity, altered bowel motility, neurotransmitter imbalances, and inflammation.

Herbal medicines have been used in Asia for a long time. An increasing number of IBS patients are beginning to receive complementary and alternative medicines in the West, most frequently herbal remedies (43%)[4]. Patients may seek HM for symptomatic relief when conventional medicines (CM) are unsuccessful. In such situations, an important question is whether herbal medicines are effective and safe for IBS patients. In the present study, we systematically reviewed the literature and evaluated the effects of HM as well as their potential adverse events in patients with irritable bowel syndrome.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Search strategy

We carried out a literature search using MEDLINE (1966-2005), EMBASE (1980-2005), Cochrane Database (1992-2005), TCMLARS Database (1984-2005), CJA Full-Text Database (1994-2005), and Chongqing VIP Database (1989-2005) for relevant randomized controlled clinical trials, meta-analysis and systematic reviews published in all languages until October 2005. We used MeSH terms including ‘irritable bowel syndrome, functional colonic disease, drugs, Chinese medicines, traditional medicines, herbal medicines, alternative medicines, complement medicines, plant, oriental traditional medicine’ for the database search.

In addition, a hand search of reference lists, review articles, editorials and abstracts from major meetings was also conducted to supplement the electronic search. We included articles published in all languages. Titles and abstracts of all potentially relevant studies were screened before retrieval of the full articles. However, if the title and the abstract were ambiguous, the full articles were scrutinized. Two independent reviewers (J.S and H-X. L) participated in the literature search. Any disagreements were resolved by discussions in order to reach a consensus.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The following inclusion criteria were used: (1) Diagnostic criteria used for IBS were ROMEI[5] or ROMEII[6] criteria or the 1986 National symposium on chronic diarrhea (Chengdu China) criteria[7]; (2) Study design with randomized controlled clinical trials, irrespective of blinding; (3) Studies using HM alone for treating IBS in the treatment groups; (4) Identification and description of adverse events; (5) The treatment group received orally administered HM; (5) The control groups received placebo, CM or no treatment.

We excluded studies in which HM was used in combination with CMs, in children and in control groups. Administration of HM by other routes such as injections were also excluded.

Information on HM products derived from a single herb, Chinese proprietary medicines, complex extracts of different herb preparations such as decoction, tablet, capsule, pill, powder and plaster were collected. Standardized extracts of whole plants were included, but isolated ‘active’ phytochemical ingredients were excluded as these are generally considered as plant chemical products.

Data extraction

Data was collected independently by the reviewers. Any disagreement between the reviewers was resolved by discussion in order to achieve consensus.

Assessment of study quality

The reviewers also assessed independently the quality of each study by Jadad scale[8] and Cochrane Handbook[9].

Statistical analysis

The relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were calculated using raw data derived from each study. Intention-to-treat analysis was performed if possible. Meta-analyses was performed with either fixed effects model or random effects model according to the presence or absence of heterogeneity when HM was compared with control. Statistical analysis was performed with RevMan 4.2 to detect any bias in studies using the funnel plot.

RESULTS

Our initial search generated 572 citations. After analyzing the titles and abstracts, and reading the full text articles, only 22 studies[10–31] with 25 arms involving 1279 patients and 763 controls met the predefined inclusion criteria. Eighteen of the studies were conducted in China and published in Chinese, four were published in English, one each from Australia[11] and Israel[20], and two from Germany[29,31] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the analysis

| Study ID | Year | n | Mean age | Sex (male %) | Study quality | Herbal medicine | Type of herbs | Control | Length (wk) | Follow-up (wk) |

| Gao[10] | 1992 | 111 | 34 | 39 | L | Lizhong Huoxie decoction | C.F | Oryzanol, Nifedipine | 4 | 52 |

| Bensoussan[11] | 1998 | 116 | 47 | 35 | H | Individualized CHM | C.F | Placebo | 16 | 14 |

| Standard Formula | C.F | |||||||||

| Zhao[12] | 2000 | 233 | 39 | 34 | L | Tongxie Yaofang modified decoction | C.F | Salazosulfapyridine | 3 | n.r |

| Diphenoxylate, Anisodamine, Amitriptyline, Placebo | ||||||||||

| Lei[13] | 2000 | 96 | 39 | 56 | L | Huatan Liqi Tiaofu decoction | C.F | Smecta | 3 | n.r |

| Wang[14] | 2000 | 96 | 39 | 49 | L | Geqin Shujiang Shaocao decoction | C.F | Smecta, vitB | 3 | n.r |

| Ye[15] | 2002 | 80 | 37 | 46 | L | Xianshi Capsule | C.F | Dicetel, Smecta | 8 | n.r |

| Deng[16] | 2002 | 62 | 38 | 35 | L | Huanchang decoction | C.F | Anisodamine, Oryzanol | 3-6 | 52 |

| Zeng[17] | 2002 | 98 | 38 | 46 | L | Congpi Lunzhi Formula | C.F | Bacillus Licheniformis | 6 | n.r |

| Ge[18] | 2002 | 57 | 40 | 44 | L | Xiangsha Liujunzi decoction | C.F | Diazepam, Propantheline, Domperidone | 2 | n.r |

| Zhou[19] | 2002 | 105 | n.r | n.r | L | Shunji mixture | C.F | Bitinal | 4 | n.r |

| Sallon[20] | 2002 | 80 | 47.9 ± 2.11 | 38 | H | Padma Lax (Tibetan herbal formula) | C.E | Placebo | 12 | n.r |

| 46.3 ± 2.93 | ||||||||||

| Ma[21] | 2003 | 204 | 36 | 48 | L | Changkang Capsule | C.F | Amitriptyline | 4 | n.r |

| Wang[22] | 2003 | 104 | 53 | 53 | L | Wuma Simo decoction | C.F | Cisapride | 2 | n.r |

| Liu[23] | 2003 | 77 | 37 | 36 | L | Gegan Qinlian Pellet | C.F | Nifedipine | 3 | n.r |

| Li[24] | 2003 | 101 | 39 | 68 | L | Changning Yin decoction | C.F | Diphenoxylate | 5 | n.r |

| Shen[25] | 2003 | 47 | 41.6 ± 12.81 | 57 | L | Changjitai decoction | C.F | Dicetel | 8 | n.r |

| 42.3 ± 14.73 | ||||||||||

| Zhao[26] | 2004 | 84 | 44 | 44 | L | Liyiting decoction | C.F | Dicetel | 6 | n.r |

| Xiao[27] | 2004 | 167 | 37 | 41 | L | Tongxie Yaofang plus sini san decoction (similar with Tongxie Yaofang modified decoction) | C.F | Salazosulfapyridine Diphenoxylate, Anisodamine, Amitriptyline, Placebo | 2 | n.r |

| Gao[28] | 2004 | 98 | 36 | 35 | L | Tongxie yihao capsule | C.F | Dicetel, Domperidone, Loperamide, Doxepin | 4 | 24 |

| Madisch[29] | 2004 | 208 | 47 | 40 | H | 1 STW5 | C.E | Placebo | 4 | n.r |

| 2 STW5-II | C.E | |||||||||

| 3 Bitter Candytuft | M.E | |||||||||

| Bo[30] | 2004 | 92 | 38.8 ± 1.71 | 41 | L | Jiejing Yiji decoction | C.F | Cerekinon | 2 | 4 |

| 41.3 ± 1.73 | ||||||||||

| Brinkhaus[31] | 2005 | 106 | 47.2 ± 11.71 | 37 | H | 1 Curcama | M.E | Placebo | 18 | n.r |

| 49.5 ± 14.52 | 2 Fumitory | M.E | ||||||||

| 49.0 ± 9.13 |

H: High quality study; L: Low quality study; C.F: Complex formulation of herbs; C.E: Complex extracts of different herbs; M.E: Mono-extract of single herb.

The first treatment group;

The second treatment group;

The control group; n.r: Not reported.

Three studies[11,20,29] used computer software and two[21,25] used random number tables to generate the allocation sequence. Four studies[11,20,29,31] used an adequate concealed allocation method of randomization. Six studies[11,12,20,27,29,31] used placebo as control, four of these studies[11,20,29,31] were considered to be adequate, while two[12,27] demonstrated an inadequate comparison between placebo and CTM decoction; Four studies[11,20,29,31] provided statistical data with intention-to-treat protocol.

Using the Jadad Score and Cochrane handbook, four studies[11,20,29,31] were judged to be of high quality, whereas the remaining reports were of poor quality.

Efficacy of herbal medicines

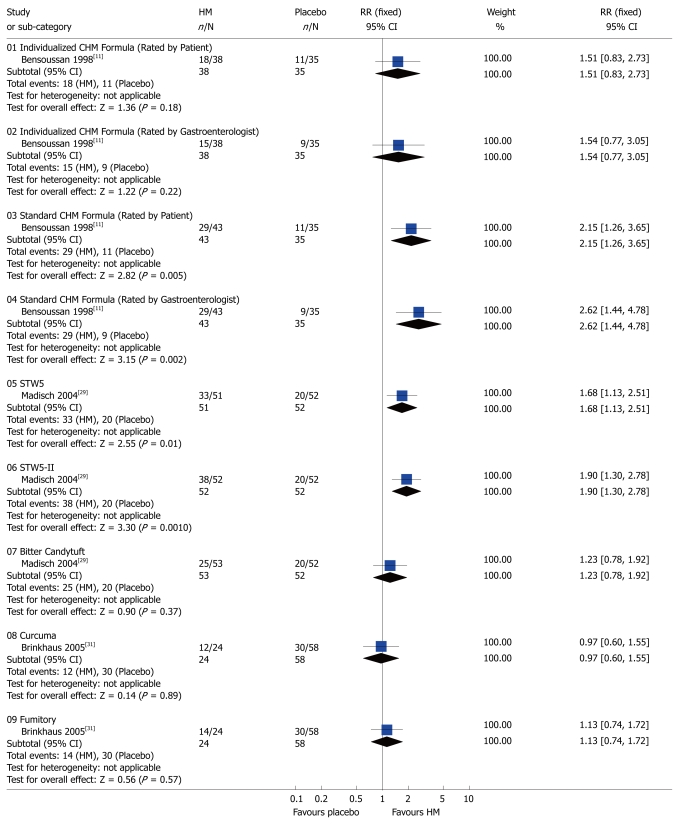

Global symptoms of IBS: Two studies[11,29] with 3 HMs showed significant benefit compared to placebo with respect to the global improvement of IBS symptoms: standard CHM formula[11] (RR 2.15; 95% CI: 1.26-3.65 rated by patient and RR 2.62; 95% CI: 1.44-4.78 assessed by gastroenterologist), STW5[29] (RR 1.68; 95% CI: 1.13-2.51), STW5-II[29] (RR 1.90; 95% CI: 1.30-2.78) (Figure 1). The following seven CHMs using complex herbal formulas appeared to be effective in improving global IBS symptoms compared to CM: Lizhong huoxie decoction[10] (RR 1.40; 95% CI: 1.11-1.76), Huatan Liqi Tiaofu decoction[13] (RR 1.24; 95% CI: 1.05-1.47), Geqin Shujiang Saocao decoction[14] (RR 1.24; 95% CI: 1.05-1.47), Huanchang decoction[16] (RR 1.41; 95% CI: 1.08-1.84), Congpi Lunzhi Formula[17], (RR 1.74; 95% CI: 1.35-2.24), Xiangsha Liujunzi decoction[18] (RR 1.28; 95% CI: 1.00-1.63, P = 0.015), and Shunji mixture[19] (RR 1.23; 95% CI: 1.01-1.49).

Figure 1.

Comparison of herbal medicine and placebo (Outcome: global improvement of symptoms). HM: Herbal medicine; RR: Relative risk; CI: Confidence interval; Fixed: Fixed effects model.

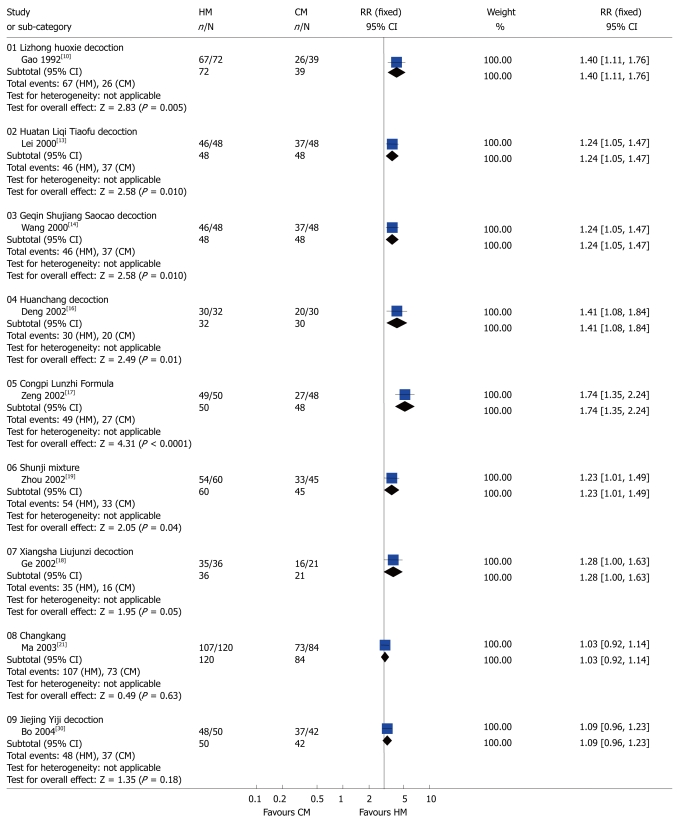

By contrast, the following compounds were not effective in the treatment of global IBS symptoms compared to placebo or CM: Individualized CHM[11] (RR 1.51; 95% CI: 0.83-2.73 assessed by patients and RR 1.54; 95% CI: 0.77-3.05 assessed by gastroenterologist), Bitter candytuft[29] (RR 1.23; 95% CI: 0.78-1.92), Curcuma [31] (RR 0.97; 95% CI: 0.60-1.55), Fumitory[31] (RR 1.13; 95% CI: 0.74-1.72) (Figure 1), Changkang Capsule[21] (RR 1.03; 95% CI: 0.92-1.14), and Jiejing Yiji decoction[30] (RR 1.09; 95% CI: 0.96-1.23) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Comparison of herbal medicine and conventional medicine (Outcome: Global improvement of symptoms). HM: Herbal medicine; CM: Conventional medicine; RR: Relative risk; CI: Confidence interval; Fixed: Fixed effects model.

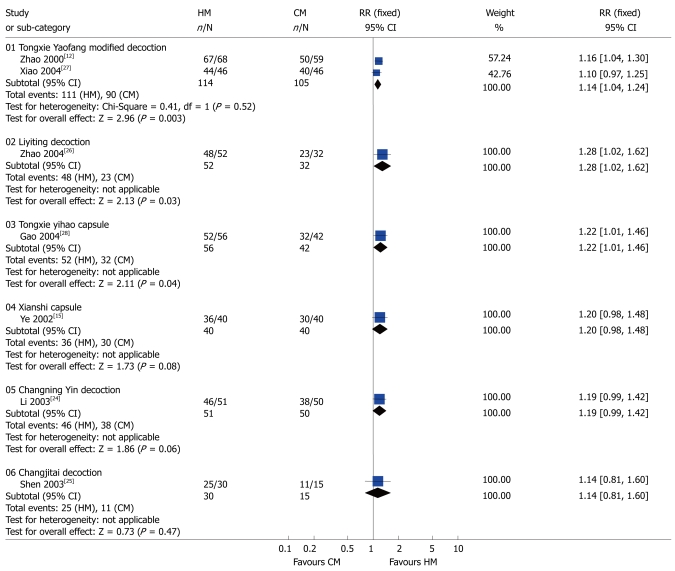

Diarrhea: As shown in Figure 3, a meta-analysis of Tongxie Yaofang modified decoction[12] and Tongxie Yaofang plus Sini San decoction[27] (RR 1.14; 95% CI: 1.04-1.24) showed that compared to CM these products had antidiarrheal effects in patients with diarrhea-predominant IBS patients. We combined the data from these two studies[12,27] since their herbal ingredients and dosages were very similar. Their effects were similar to Liyiting decoction[26] (RR 1.28; 95% CI: 1.02-1.62), and Tongxie yihao capsule[28] (RR 1.22; 95% CI: 1.01-1.46).

Figure 3.

Comparison of herbal medicine and conventional medicine (Outcome: diarrhea). HM: Herbal medicine; CM: Conventional medicine; RR: Relative risk; CI: Confidence interval; Fixed: Fixed effects model.

Three studies demonstrated an insignificant improvement in diarrhea: Xianshi Capsule[15] (RR 1.20; 95% CI: 0.98-1.48), Changning Yin decoction[24] (RR 1.19; 95% CI: 0.99-1.42), Changjitai decoction[25] (RR 1.14; 95% CI: 0.81-1.60) (Figure 3).

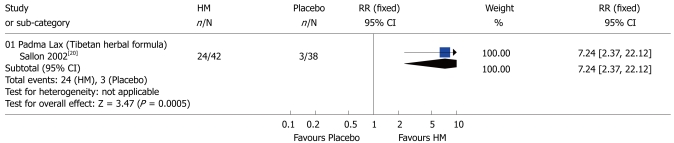

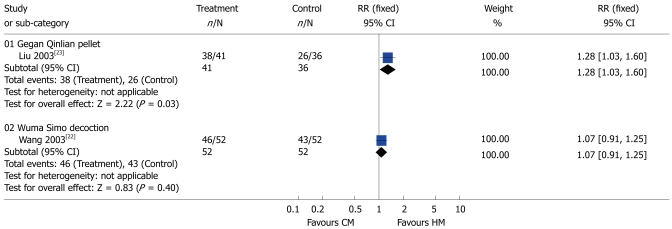

Constipation: One study[20] showed that compared to placebo Padma Lax was more effective in relieving symptoms in patients with constipation-predominant IBS (RR 7.24; 95% CI: 2.37-22.12) (Figure 4). Similarly, another study[23] demonstrated that Gegan Qinlian pellet was therapeutically effective (RR 1.28; 95% CI: 1.03-1.60). By contrast, Wuma Simo decoction[22] had no advantages over CMs in the patients with constipation-predominant IBS (RR 1.07; 95% CI: 0.91-1.25) (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Comparison of herbal medicine and placebo (Outcome: constipation). HM: Herbal medicine; RR: Relative risk; CI: Confidence interval; Fixed: Fixed effects model.

Figure 5.

Comparison of herbal medicine and conventional medicine (Outcome: constipation). HM: Herbal medicine; CM: Conventional medicine; RR: Relative risk; CI: Confidence interval; Fixed: Fixed effects model.

Therapeutic period and follow-up

The duration of treatment was 8 weeks or more in five studies[11,15,20,25,31], and 5 or 6 wk in three studies[17,24,26]. In one study[16] the treatment duration was 3-6 wk, whereas the other studies[10,12–14,19,21,23,28,29] lasted 3 or 4 wk, while the shortest[18,22,27,30] period of the treatment was only 2 wk. Five studies[10,11,16,28,30] reported follow-up assessment after herbal medicine treatment. Two[10,28] reported that the symptom recurrence rates were lower in the treatment group compared to the conventional treatment group (25.5% vs 60%; 23.1% vs 50%, P < 0.01), after one-year and one-half-year respectively, following completion of the treatment. Another study[11] presented the result as bowel symptom scale. There was significant improvement in the individualized group (75%), and standard group (63%) compared with placebo group (32%) after 14 wk of follow-up. One study[16] reported the number of subjects that were lost to follow-up, but the reasons were not provided. Another study[30] reported symptom recurrence in 3 of 48 patients in the treatment group after 2 wk without treatment.

Adverse effects of herbal medicine

In the total study group of 1279 patients, only 15 adverse events in 47 subjects were observed (Table 2). The most common symptoms were abdominal distention, constipation and abdominal pain. None of the subjects developed any serious adverse events or abnormal laboratory tests. The percentage of adverse events associated with HM was 3.67% (95% CI: 2.64-4.71%) in the 1279 patients in the different treatment groups.

Table 2.

The type and frequency of adverse events reported in the 22 studies included in the analysis (n = 1279)

| Adverse events | Number of adverse events | Percentage | 95% CI |

| Distention | 9 | 0.70 | 0.32-1.34 |

| Diarrhea | 8 | 0.63 | 0.27-1.23 |

| Abdominal pain | 6 | 0.47 | 0.17-1.02 |

| Constipation | 5 | 0.39 | 0.13-0.91 |

| Dizziness and sleepiness | 4 | 0.31 | 0.09-0.80 |

| Headaches | 4 | 0.31 | 0.09-0.80 |

| Nausea | 3 | 0.23 | 0.05-0.69 |

| Gastrointestinal discomfort | 1 | 0.08 | 0.002-0.44 |

| Upper gastrointestinal discomfort | 1 | 0.08 | 0.002-0.44 |

| Loss of hair | 1 | 0.08 | 0.002-0.44 |

| Pruritus | 1 | 0.08 | 0.002-0.44 |

| Paraesthesia | 1 | 0.08 | 0.002-0.44 |

| Disturbance | 1 | 0.08 | 0.002-0.44 |

| Hoarseness | 1 | 0.08 | 0.002-0.44 |

| Shortness of breath and chest pain | 1 | 0.08 | 0.002-0.44 |

| Total | 47 | 3.67 | 2.73-4.87 |

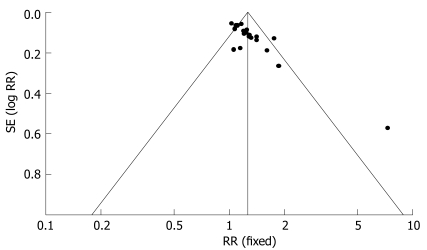

Bias analysis

Funnel plots indicated an asymmetry (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Funnel plot. Fixed: Fixed effects model; RR: Relative risk.

DISCUSSION

In the present review, 3 out of the 4 good quality studies[11,20,31] demonstrated 4 different herbal interventions: one Chinese herbal medicine (standard formula), one Tibetan herbal formula (Padma Lax) and two complex extracts of herbs: STW5 and STW5-II which could potentially relieve abdominal pain, constipation, diarrhea and alternating constipation and diarrhea. Moreover, three[11,29,31] out of these four studies showed that four interventions including one individualized formula and three mono-extracts of single herb (Bitter Candytuft, Curcama and Fumitory) were not effective in IBS. We recognized that some complex herbal formulas may improve IBS symptoms, whereas three mono-extracts of single herbs had no beneficial effect. A possible explanation for these findings is that the therapeutic effect may be enhanced by the synergic actions of compounds in a mixture of different herbs.

Twelve[10,12–14,16–19,23,26–28] out of the 18 poor quality studies showed that some Chinese herbs formulas, such as, Huatan Liqi Tiaofu decoction, Tongxie Yaofang modified and Tongxie Yaofang plus Sini San decoction, Geqin Shujiang Saocao decoction, Huanchang decoction, Congpi Lunzhi Formula, Xiangsha Liujunzi decoction, Shunji mixture, Gegan Qinlian Pellet, and Liyiting decoction were more beneficial than CMs in the treatment of IBS.

However, these studies revealed several methodological flaws. We found that the longest duration of treatment was 18 wk, while the shortest was just 2 wk, and only 5 studies lasted more than 8 wk. The most frequent treatment duration was 3-4 wk. With such a short period of treatment, it is hard to reach the therapeutic goal in IBS. Some studies reported the long-term effects of herbs and the rate of symptom recurrence. Thus, it is necessary to have a relatively long treatment duration with herbal medicines as well as the duration of the follow-up period; Funnel plot of inclusion trials indicated asymmetry, the major interpretation is the presence of publication bias and variable methodological quality. In the studies that we reviewed, 18 out of 22 were conducted in China and published in Chinese. Chinese studies more frequently showed favorable therapeutic results compared to articles in English, particularly those with a high rate of positive outcome (99%)[32]. The large number of poor quality studies is another source of bias. Furthermore, the small size of studies and the variability of the control treatment may cause asymmetry of the funnel plot. We noticed that most of the studies with Chinese herbs were of poor methodological quality and would not provide strong evidence to confirm the efficacy of CHM. However, the lack of good evidence supporting the effectiveness of CHM does not mean that these preparations are not effective in the treatment of IBS, instead we need to improve the methodological quality of trials in order to verify the efficacy of CHM as a therapeutic approach. We agree with the opinion of Liu[33] that the potential beneficial effects of CHM need to be confirmed in rigorous trials with well-designed, randomized, double blinded, placebo controlled studies. A good example is the study performed by Bensoussan and colleague[11].

There is growing interest in placebo response in patients with IBS. A systematic review of RCTs showed that global improvement in IBS symptoms with placebo was 40.2% (range 16%-71.4%)[34].Other investigators have reported placebo response rate of 57% in IBS[35]. Placebo response rate correlated with factors such as frequency of intervention, methodological quality of study, duration of the study, the patient-practitioner interaction and the diagnosis treated[34,36–38]. Since the number of studies using placebo were small, we did not explore the response effect of placebo in the present study.

In the 22 trials that we reviewed, there were only 15 adverse events associated with HM. These were abdominal distention, constipation, abdominal pain, diarrhea, dizziness and hypersomnia, headache and nausea. However, no serious side effects or abnormalities of laboratory parameters such as liver function, renal function or haematological tests were reported with the treatment. Studies conducted in the West reported more adverse events than those from China. It is possible that because of the lack of rigorous monitoring, several adverse effects including serious events may not have been reported. Similarly, because of publication bias, adverse events related to herbal medicine may not be reported properly.

In summary, the use of HM for treating IBS is increasing worldwide. Most of the studies included in our review showed a beneficial effect on IBS symptoms. However, the methodological quality of the studies was variable, with 82% being of poor quality which may have overestimated the effectiveness of treatment. Although adverse events arising from the use of herbs were mild and infrequent, HM should be used with caution because of the reasons discussed above. It is therefore necessary to conduct Level I studies in order to provide evidence for Grade A recommendations[39] and clarify whether Chinese herbal medicines are reliable and safe therapy in IBS.

COMMENTS

Background

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common functional bowel disorder that affects the patient’s quality of life. No single treatment is reliably effective, and an increasing number of patients worldwide are seeking herbal medicines to cure their illness.

Research frontiers

We assessed the efficacy and adverse events of herbal medicines in IBS.

Innovations and breakthroughs

We made a comprehensive search of studies using herbal medicines for the treatment of IBS. The studies were analyzed to determine if herbal medicines are appropriate for IBS patients.

Applications

Based on this evaluation, we concluded that herbal medicines could not be reliably recommended because of methodological flaws in the studies. Further studies of better methodological quality should be carried out to determine the efficacy of herbal medicines in IBS.

Peer review

The authors explored the efficacy and safety of herbal medicines (HM) in the treatment of IBS. It was concluded that herbal medicines have therapeutic benefit in IBS.

Peer reviewer: Christina Surawicz, MD, Harborview Medical Center, 325 9th Ave, #359773, Seattle WA 98104, United States

S- Editor Zhu LH L- Editor Anand BS E- Editor Ma WH

References

- 1.Spiller RC. Irritable bowel syndrome. Br Med Bull. 2004;72:15–29. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldh039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cremonini F, Talley NJ. Irritable bowel syndrome: epidemiology, natural history, health care seeking and emerging risk factors. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2005;34:189–204. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gwee KA. Irritable bowel syndrome in developing countries--a disorder of civilization or colonization? Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2005;17:317–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2005.00627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spanier JA, Howden CW, Jones MP. A systematic review of alternative therapies in the irritable bowel syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:265–274. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.3.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thompson WG, Greed FH, Drossman DA, Heaton KW, Mazzacca G. Functional bowel disorders and functional abdominal pain. Gastroenterology International. 1992;5:75–91. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thompson WG, Longstreth GF, Drossman DA, Heaton KW, Irvine EJ, Muller-Lissner SA. Functional bowel disorders and functional abdominal pain. Gut. 1999;45 Suppl 2:II43–II47. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2008.ii43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Symposium on Chronic Diarrhea. The Diagnostic Criteria for Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Zhonghua Xiaohuabin Zazhi. 1987;7:inside back cover. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynol necessary ds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higgins JPT, Green S.editor. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 4.2.6 [updated September 2006] In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 4, 2006. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Available from: URL: http//www. cochrane.org/resources/handbook:79-87. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao ZJ, Zeng XZ. 72 Cases Clinical Observations on the Treatment of Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Chinese Medicine. Hunan Zhongyi Zazhi. 1992;4:10–11. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bensoussan A, Talley NJ, Hing M, Menzies R, Guo A, Ngu M. Treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with Chinese herbal medicine: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;280:1585–1589. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.18.1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao LJ, Li SL, Song SY, Xu DQ, Qin YS. A Contrastive Observation in Treatment of 223 patients Diarrhea-Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome between Chinese Medicine and Western Medicine. Henan Zhongyi. 2000;20:35. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lei CF, Chu LZ. Treatment Irritable Bowel Syndrome Based on ‘Tang’ in 48 patients. Shandong Zhongyi Zazhi. 2000;19:206. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang ZH. Clinical Effect of Geginshujiangshaocaotang on Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Hebei Zhongyi. 2000;22:738–739. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ye B, Shan ZW. Clinical Study of Xianshi Capsule for Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Nanjing Zhongyiyao Daxue Xuebao. 2002;18:273–274. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dang ZM, Yang Q. Clinical Observation of Huanchang decoction in 32 patents with Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Anhui Zhongyi Linchuang Zazhi. 2002;14:113–114. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zeng BM. Treatment of 50 patients with irritable Bowel Syndrome Based on Pi. Sichuan Zhongyi. 2002;20:39–40. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ge W. Treatment of Irritable Bowel Syndrome with a traditional Chinese Medicine‘Xiangsha Liujunzi decoction’. Hubei Zhongyi Zazhi. 2002;24:34. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou FS, Wu WJ, Huang ZX. Effect of Shunji mixture in Treating Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Guangzhou Zhongyiyao Daxue Xuebao. 2002;19:269–270. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sallon S, Ben-Arye E, Davidson R, Shapiro H, Ginsberg G, Ligumsky M. A novel treatment for constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome using Padma Lax, a Tibetan herbal formula. Digestion. 2002;65:161–171. doi: 10.1159/000064936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma BH, Zhou T. Observation of therapeutic effect of Changkang Capsule for Treatment of 120 patients Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Zhongyiyao Xuekan. 2003;21:1748, 1779. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang JH, Tian XD, Dong SX. Wuma Simo decoction for Treating 52 patients of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Shiyong Yiji Zazhi. 2003;10:686. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Q, Lin Y, Xu LT. Clinical Study on Gegen Qinlian pellet for Irritable Bowel Syndrome Comparing with Nifedipine. Shiyong Zhongxiyi Jiehe Linchuang. 2003;3:9. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li FL, Cao ZC, Zhang YS. Observation of Therapeutic Effect of Changning Yin decoction for Treatment Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Zhongguo Zhongyiyao Keji. 2003;10:334. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shen Y, Cai G, Sun X, Zhao HL. Randomized Controlled Clinical Study on Effect of Chinese Compound Changjitai in Treating Diarrheic Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Zhongguo Zhongxiyi Jiehe Zazhi. 2003;23:823–825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao LY, Chu HM. To Observe the Clinical effects of Liyiting in the Treatment of Irritable Bowel Syndrome of Diarrhea Pattern. Shanghai Zhongyiyao Zazhi. 2004;38:22–23. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xiao L. Traditional Chinese Medicine Integrated with Western Medicine for Diarrhea-Predominant Treating Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Henan Zhigong Yixueyuan Xuebao. 2004;16:386–387. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gao XQ, Lei FY. Curative Effect Observation of Curing Intestines Diarrhea with No.1 Capsule. Zhonghua Shiyong Zhongxiyi Zazhi. 2004;4:1348–1349. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Madisch A, Holtmann G, Plein K, Hotz J. Treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with herbal preparations: results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, multi-centre trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:271–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bo YK, Zhang JB. Jiejing Yiji decoction for Treating 50 Patients of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Zhongyi Zazhi. 2004;45:367–368. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brinkhaus B, Hentschel C, Von Keudell C, Schindler G, Lindner M, Stutzer H, Kohnen R, Willich SN, Lehmacher W, Hahn EG. Herbal medicine with curcuma and fumitory in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:936–943. doi: 10.1080/00365520510023134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vickers A, Goyal N, Harland R, Rees R. Do certain countries produce only positive results? A systematic review of controlled trials. Control Clin Trials. 1998;19:159–166. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(97)00150-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu JP, McIntosh H, Lin H. Chinese medicinal herbs for asymptomatic carriers of hepatitis B virus infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;19:CD002231. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patel SM, Stason WB, Legedza A, Ock SM, Kaptchuk TJ, Conboy L, Canenguez K, Park JK, Kelly E, Jacobson E, et al. The placebo effect in irritable bowel syndrome trials: a meta-analysis. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2005;17:332–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2005.00650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lembo A, Camilleri M. Chronic constipation. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1360–1368. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bernstein CN. The placebo effect for gastroenterology: tool or torment. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1302–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pitz M, Cheang M, Bernstein CN. Defining the predictors of the placebo response in irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:237–247. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00626-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walach H, Sadaghiani C, Dehm C, Bierman D. The therapeutic effect of clinical trials: understanding placebo response rates in clinical trials--a secondary analysis. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005;5:26. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-5-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fennerty MB. Traditional therapies for irritable bowel syndrome: an evidence-based appraisal. Rev Gastroenterol Disord. 2003;3 Suppl 2:S18–S24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]