Abstract

Proton beam is useful to target tumor tissue sparing normal cells by allowing precise dose only into tumor cells. However, the cellular and molecular mechanisms by which proton beam induces tumor cell death are still undefined. We irradiated three different tumor cells (LLC, HepG2, and Molt-4) with low energy proton beam (35 MeV) with spread out Bragg peak (SOBP) in vitro, and investigated cell death by MTT or CCK-8 assay at 24 h after irradiation. LLC and HepG2 cells were sensitive to proton beam at over 10 Gy to induce apoptosis whereas Molt-4 showed rather low sensitivity. Relative biological effectiveness (RBE) values for the death rate relative to γ-ray were ranged from 1.1 to 2.3 in LLC and HepG2 but from 0.3 to 0.7 in Molt-4 at 11 d after irradiation by colony formation assay. The typical apoptotic nuclear DNA morphological pattern was observed by staining with 4'-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Tiny fragmented DNA was observed in HepG2 but not in Molt-4 by the treatment of proton in apoptotic DNA fragment assay. By FACS analysis after stained with FITC-Annexin-V, early as well as median apoptotic fractions were clearly increased by proton treatment. Proton beam-irradiated tumor cells induced a cleavage of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1) and procaspases-3 and -9. Activity of caspases was highly enhanced after proton beam irradiation. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) were significantly increased and N-acetyl cysteine pretreatment restored the apoptotic cell death induced by proton beam. Furthermore, p38 and JNK but not ERK were activated by proton and dominant negative mutants of p38 and JNK revived proton-induced apoptosis, suggesting that p38 and JNK pathway may be activated through ROS to activate apoptosis. In conclusion, our data clearly showed that single treatment of low energy proton beam with SOBP increased ROS and induced cell death of solid tumor cells (LLC and HepG2) in an apoptotic cell death program by the induction of caspases activities.

Keywords: alpha particles; apoptosis; caspases; neoplasms; radiation, ionizing; reactive oxygen species

Introduction

The use of proton beam in radiation therapy has increased considerably in the past few years (Levin et al., 2005; MacDonald et al., 2006). When charged particles enter the patient's body their specific energy per unit of length deposited along the track (linear energy transfer, LET) increases with decreasing particle velocity, giving rise to a sharp maximum in ionization near the end of the range (the Bragg peak). Optimization of the doses to induce the cell death of various cancer cells at the Bragg peak is very important to reduce the side effects and maximize the therapy (Belli et al., 2000; Bettega et al., 2000). In the spread-out Bragg peak (SOBP), particles have a broad spectrum of energy with covering sample depth and the SOBP has a higher LET than the entrance beam. The relative biological effectiveness (RBE) of protons for cell survival varies with LET. Actual RBE value is important for the determination of the effective dose to the tumor region. When irradiated with low energy proton, RBE is increased in non-human cell line (Belli et al., 1989, 1998). RBE values for proton beam therapy with SOBP relative to γ-ray are evaluated in vitro and in vivo system; for various cells ranging from 0.7 to 2.1 (Paganetti et al., 2002).

The mitochondria are central organelle for both caspase-dependent and -independent death pathway (reviewed in Tsujimoto, 2003). In a death inducing signaling pathway, procaspase-8 undergoes auto-proteolytic activation in which proapoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins are induced. This can lead to triggering of the enzymatic activity of downstream effectors, such as caspase-3 and -7 (extrinsic pathway). In different death stimuli from death receptor signal, such as ROS or increased intracellular calcium concentration, mitochondrial cytochrome c is released from mitochondria into cytosol, where it binds to apaf-1. Apaf-1 and cytochrome c complex recruit and activate caspase-9 in the presence of ATP (Igney and Krammer, 2002). Inhibitors of apoptosis (IAPs) prohibit caspase-3 activation by caspase-9 (intrinsic pathway). In caspase-independent pathway, mitochondria release factors including apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) and endonuclease G (EndoG). When mitochondrial permeability transition is induced following an apoptotic stimulus, soluble factor such as AIF and EndoG translocate into nucleus to induce chromatin condensation in a caspase-independent manner (Cregan et al., 2004).

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) regulates a broad array of signal transduction pathways that regulate various biological processes including gene expression, cell growth, differentiation, and apoptosis. ROS caused by various stressors such as high glucose, angiotensin II, TNF-α and irradiation enhance apoptosis of various tumor cells (Engel and Evens, 2006). Activation of p38 and JNK MAPKs has been reported to contribute to ROS-induced apoptosis (Fuchs et al., 1998; Benhar et al., 2002; Samuni et al., 2005; Bubici et al., 2006). By the γ irradiation, p53, caspase-3 and JNK/SAPK are reported to be associated with cell cycle arrest and apoptosis (Samuni et al., 2005). It is well identified that ROS may be involved in γ irradiation-induced apoptosis of cancer cells as well as normal cells (Mishra, 2004). The activation of p53 is typically induced by DNA damaging stresses, and in ROS-induced apoptosis ROS appears to be generated downstream of p53-induced caspase activation (Ueda et al., 2002).

Cell death induced by proton beam is identified as apoptosis (Di Pietro et al., 2006). The study investigated that genes involved in various phases of apoptosis are checked by RT-PCR and used LET instead of SOBP of proton beam. Because apoptosis is the process tightly regulated by various functional proteins in physiological cell death program it is necessary to check the protein level and functional protein activity as well as cellular and molecular events in proton (with SOBP)-induced apoptosis.

In present study, we investigated whether proton beam induced tumor cell death in several cancer cell lines in vitro with a specific strategy to fit the beam energy at cell surface with SOBP and lose the energy just after the cells were located and compared the sensitivity of cancer cells with γ ray. In addition, we identified that the proton-induced cancer cell death was through apoptotic pathway and the molecular mechanism by which proton induced apoptosis of tumor cells with a single treatment in a short term period.

Materials and Methods

Cell cultures

Lewis lung carcinoma cells (LLC), HepG2 human hepatocellular carcinoma cells and Molt-4 human leukemia cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS (heat inactivated, Hyclone, Logan, UT) and 1 × antibiotics (100 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin, all from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) at 37℃ in a humidified atmosphere incubator containing 5% CO2.

Proton beam irradiation and dosimetry

On a day after plating, cells were irradiated with proton beam. At the MC50 Cyclotron (Scanditronix, Sweden) at the Korea Cancer Center Hospital, Seoul, Korea, 35 MeV protons were produced at the Bragg peak. A 12.5 cm2 flask or 96-well plate was used to fit beam geometry, on which the cells were plated. The beam was extracted for SOBP with which the high LET was repeated at broad region as a function of depth of flask or plate and media on which the cells were plated (Figure 1). It was assumed that the thickness of the cell monolayer was between 3-6 µm and that of the media was 2 cm. Just before the irradiation, the flask or 96-well plate was fixed vertically with a tape, facing the horizontal beam. Cells were irradiated at the chosen position at single dose level of 1, 2, 5, 10, 50, 100, and 200 Gy. The average dose rate was 2.31 Gy/s. We used radiochromic film (GAF-MD55) for an in situ measuring tool of the dose at each beam irradiation. Irradiation of cancer cells with γ-rays were performed using 137Cs in IBL 437C γ-irradiator (CIS Bio International, France) at Kyungpook National University Hospital in Daegu. The average dose rate was 1 Gy/min. All cell irradiations were performed in air at room temperature. RBE values were calculated with the ratio of death rates of proton beam irradiated cells versus those of γ-irradiated cells in each dose at the same time points.

Figure 1.

Measured dose in culture plate versus distance from the sample stage for the 35 MeV proton beam produced at the Cyclotron at the Korea Cancer Center Hospital. Sample stage was located vertically to the direction of beam exposure and culture dishes were adhered closely onto the stage in the bottom in which cells were plated. The distance 0 was estimated the entrance point to the plastic plate on which cells were plated. Thus distance from the stage 4.5 mm within SOBP in highest LET should be enough to cover all cells plated in the area (5 × 5 cm; height × width of sample located within plates).

Cell viability assays

Cells were plated at 1 × 104 cells per well in a 96-well plate and incubated for one day at 37℃ in a CO2 incubator. Cell viability was measured with MTT. Viable cells were formed crystal dye which was solubilized with DMSO and measured the absorbance at 540 nm using a microplate reader (Lab system, Multiscan MS). For floating cells, leukemia cells, viable cells were measured by Cell Counting Kit-8 (Dojindo Molecular Tech, Kumamoto, Japan), using [2-(2-methoxy-4-nitrophenyl)-3-(4-nitrophenyl)-5-(2,4-disulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium, monosodium salt] at 450 nm at 1 or 3 days after proton beam irradiation. Each condition was tested in quadruplicate, the mean ± SD was calculated, and the fold induction compared to the control cells was determined.

Soft agar colony formation

A soft agar colony formation assay was done using CytoSelect 96-well Cell Transformation Assay kit (Cell Biolabs, San Diego, CA). Each well contained 50 µl of 0.6% agar in a complete medium as the bottom and feeder layer, and 75 µl of 0.4% agar in a complete medium with 2,000 cells as the top layer. On next day cells were irradiated with proton beam or γ-ray and cultured for 11 days. The number and morphology of colonies were determined with an inverted phase-contrast microscope (Olympus, Japan). Colonies were lysed with lysis buffer and detected with CyQuant GR dye for the quantification of anchorage-independent growth and measured the fluorescence with fluorometer using 485/520 filter set (Wallac Victor3 1420 mutilabel counter, PE). The data are means ± SD of three independent experiments at 11 days after the cell seeding.

Western blot analysis

Cells were treated with proton beam and harvested in a lysis buffer (iNtRon Biotech, SeongNam, Korea), and an equal amount of cellular proteins was subjected to SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membrane and blots were probed with anti-PARP-1 (Santa Cruz Biotech, Santa Cruz, CA), anti-caspase-3, -7, -8 (Stessgen, Ann Arbor MI), anti-Bcl-2, anti-Bax (Cell signaling, Danvers, MA), anti-XIAP (Stressgen), anti-survivin (Stressgen), phospho-p38, phospho-JNK/SAPK, phospho-ERK1/2 and phospho-Akt (Cell Signaling) antibodies.

DNA fragmentation assay

To determine the degradation of chromosomal DNA into nucleosome-sized fragments, a 500 µl aliquot of the lysis buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.5, EDTA, 0.2 M NaCl, 0.2% SDS, and 0.2 mg/ml proteinase K) was added to the cell pellet (2 × 105 cells) and incubated at 37℃ overnight. DNA was precipitated by ethanol, separated in a 0.8% agarose gel, and visualized under UV light.

Caspases activity analysis

Cells were lysed with a lysis buffer (iNtron Biotech). The cell lysate was incubated with caspase substrate, Ac-DEVE-pNA (Caspase-3 substrate 1, Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) at 37℃ and measured an absorbance every 10 min at 405 nm in spectrophotometer. Caspase-3 activity was determined as an average slop of increasing absorbance plot within an early time (within 60 min) using a linear regression with duplicate experiments.

FITC-Annexin V/PI staining

Apoptosis-mediated cell death of tumor cell was examined using a double staining method with FITC-labeled Annexin V (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA)/propidium iodide (PI, Sigma-Aldrich). Briefly, PBS washed cells were incubated with HEPES buffer (140 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 10 mM HEPES, pH7.4) containing 1 µg/ml Annexin V and 1 µg/ml PI at RT for 30 min. After then, cells were washed with PBS and the scatter signals of 10,000 cells were analyzed with FACS, Coulter Elite ESP Cell Sorter (Beckman).

ROS measurement

Cells were collected 4 h after proton beam irradiation and stained with 10 µM H2DCFDA for 10 min at 37℃ and then observed under a fluorescent microscope (Axiovert 200, Carl Zeiss). Intracellular ROS production was measured using an oxidant-sensitive fluorescent probe DCFH-DA with FACS analyses. Measurement of 2',7'-dichlorofluorescenin (DCF) fluorescence in cells was made at least 10,000 events/test using FACSCaliber flow cytometer (Becton-Dickinson) with a fluorescein isothiocyanate filter. Intracellular hydrogen peroxide concentration was determined using a ferric sensitive dye, xylenol orange, as described (Jiang et al., 1992).

Expression vectors and transient transfection

Transfection was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), according to the manufacturer's instruction. The dominant negative (DN) constructs of JNK-1 and DN p38 MAPK cloned in pCDNA3 and pCMV5, respectively, were kindly provided by Dr. Aree Moon (College of Pharmacy, Duksung Women's University, Seoul, Korea). Eight µg of each DN mutant plasmids was transfected into HepG2 cells plated onto 100 mm dish with a density 2 × 106 one day before. After 12 h of transfection, cells were trypsinized and plated in 96 well with a density 1 × 104. And 24 h later cells were irradiated with proton beam and cell viability was checked at 24 h after irradiation with MTT assay.

Statistical analysis

ANOVA-test was performed to assess the significance of differences among the experimental groups. The level of significance was set at P < 0.01. Results are represented as the mean ± SD (Standard deviation).

Results

Proton beam and γ-ray induced cell death in different cancer cells with a single treatment

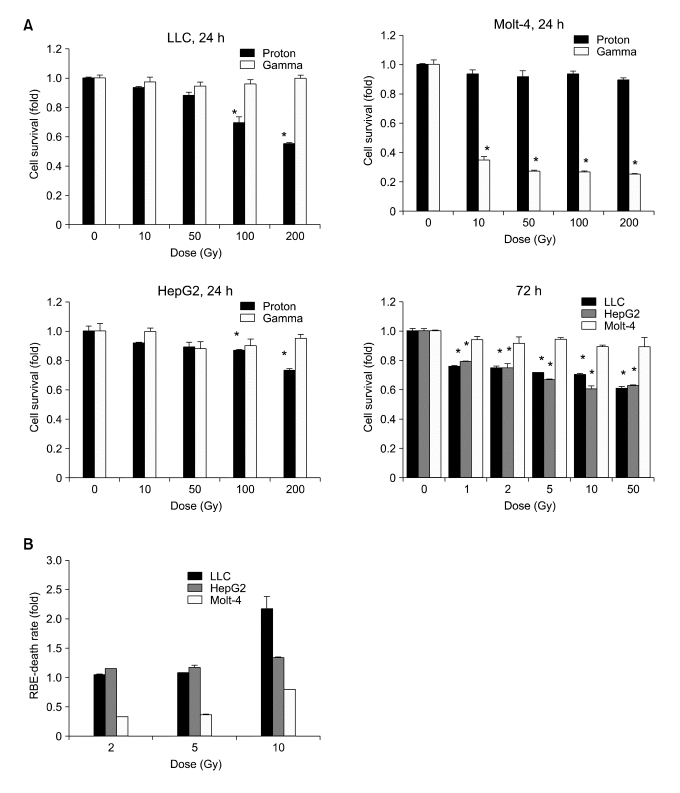

To investigate the short-term effect of proton beam and γ-ray on cancer cells, we used three different cell lines, LLC, mouse lung cancer cells, HepG2, human hepatocellular carcinoma cells and Molt-4, human leukemia cells and determined cell survival rate at 24 h after irradiation. Over 10 Gy of proton beam induced cell death in LLC and HepG2 but not in Molt-4 cells (Figure 2A). At 24 h after irradiation cell death was up to 40% in 100 Gy of proton beam-treated LLC cells, and in HepG2 cells up to 30% cells were dead by proton in 200 Gy. However, Molt-4 cells did not respond to proton even in the highest dose of 200 Gy (Figure 2B). In lower doses (1-50 Gy) proton had no effect on the cell death for 24 h, but longer incubation (72 h) after irradiation showed a significant effect on cell death as 22-35% in our in vitro system (Figure 2A, 72 h). In contrast to proton beam, when we applied γ-ray to the same tumor cell lines, γ-ray induced cell death specific to leukemia cells, Molt-4, but not in LLC or HepG2 cells. That is, Molt-4 cells were very susceptible to γ-ray, showing 75-80% of cell death induced over 10 Gy whereas γ-ray did not increase cell death in LLC or hepatoma cells even at highest dose (200 Gy) (data not shown). This result indicated that proton and γ-ray has different specificities depending on the cancer cells. And we found that the doses we used at the position of cells plated were quite optimal to observe the cancer cell death with proton beam.

Figure 2.

Effects of proton beam and γ-ray on tumor cell death. (A) Proton beam was irradiated with SOBP at high LET shown in Figure 1. Gamma-ray was also treated at the same doses with proton beam onto cells plated with same density. Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC), hepatoma (HepG2) and leukemia (Molt-4) cells were exposed to proton beam with indicated doses at 24 h after irradiation. To measure the survival rate, MTT (for LLC and HepG2) or CCK (for Molt-4) assay was performed at 24 h after irradiation. Cell survival rate in LLC and HepG2 cells were reduced in a dose-dependent manner by proton beam irradiation, but not by the γ-ray. But in Molt-4 cells γ-ray was more effective to induce cell death than proton. To further determine the effect of lower doses at 72 h after proton irradiation, 1-50 Gy of proton beam was used in three different cell lines. All data were shown as fold induction of control cell viability. Mean ± SD (n = 5). All experiments were performed in duplicate. *P < 0.01 versus control (no treatment of proton or γ-ray). (B) RBE values for the death rate relative to γ-ray in three tumor cell lines. Two thousand cells were plated on 0.4% agar in a complete media onto feeder layer with 0.6% agar in 96 well. On next day, cells were irradiated with proton or γ-ray (2-10 Gy) and cultured for 11 d. RBE values were calculated by the ratio of death rate of proton beam versus that of γ-ray. And the data were presented as the Mean ± SD (n = 5).

To obtain the RBE values for cell death of proton beam compared to the γ irradiation, a long-term colony formation assay was performed with three different cancer cells (Figure 2B). Cells were plated onto soft-agar with feeder layer and cultured for 11 days. We calculated RBE values for the death rate of tumor cells relative to that of γ-ray irradiated cells in the induction of tumor cell death for long-term effect. If RBE is above 1, the cell death rate by proton beam is higher than that by γ-ray. It was reported that the RBE values of proton beam in various cancer cells are 0.9 to 2.1 in vitro (Paganetti et al., 2002), being consistent with our result. In HepG2 cells the RBE was 1.1-1.3, meaning a higher effect than γ-ray. Colonies with LLC at 11 days after irradiation was significantly decreased by proton beam but not by γ-ray. Thus the RBE value of LLC cells was 2.3 at 10 Gy of proton. However, RBE values of Molt-4 leukemia cells were lower than that of LLC or HepG2 cells. RBE values of Molt-4 were around 0.3 at 2 or 5 Gy and 0.7 at 10 Gy, indicating that proton has little effect on the cell death of Molt-4 cells (Figure 2B). At least in our experiment, Molt-4 was more sensitive to γ-ray than other solid tumor cell types. But proton beam did induce Molt-4 leukemia cell death around 10% at highest dose (10 Gy) in early time point. Thus, proton beam might be a better hadron therapy than γ-ray for specific solid tumor cells at optimal depth with SOBP.

Proton beam induced apoptosis of tumor cells

To investigate whether the cell death induced by proton beam in HepG2 and LLC cells is processed under apoptotic mechanism, we examined at first the morphology of the cells after irradiation. At 24 h after irradiation, we observed cell morphology of LLC and HepG2 under the microscope. As shown in Figure 3A, compared to control cells, proton beam-treated cells were segregated each other but had condensed and fragmented DNA in their nucleus by DAPI staining at 24 h after irradiation. When we performed DNA fragmentation assay, proton beam treatment to sensitive HepG2 cells induced clear DNA fragmentation in agarose gel but did not induce any fragmentation in non-sensitive cells, Molt-4 (Figure 3B). To confirm this, we further performed FITC-Annexin-V staining LLC cells, detecting the apoptotic cell membrane phosphoserin residues flip-floped to the external environment. The early and median apoptotic cells (positive Annexin V population, right two sections) were increased (2.22% into 42.13 and 0.55 into 26.71%, respectively) but late apoptotic and necrotic cells (left upper section of fluorocytogram) were decreased by proton irradiation in LLC cells (1.18% into 0.09%, Figure 3C). These results suggest that proton beam causes the cancer cell death via apoptotic mechanism.

Figure 3.

Nuclear DNA fragments and FACS analysis in proton beam-irradiated cancer cells. (A) Representative pictures at 24 h showed an apoptotic morphology in LLC and HepG2 cells irradiated with proton beam (100 Gy) (each upper pictures). At 24 h after the irradiation, LLC and HepG2 cells were observed for DAPI stained nucleus (each lower pictures) with microscope (× 200). Arrows indicate fragmented and condensed DNA in the nucleus. Boxes in the corner show large magnification of representative nucleus (× 400). (B) DNA fragmentation assay was performed at 24 h after irradiated with proton beam in HepG2 (proton beam sensitive) and Molt-4 (proton beam insensitive) cells. DNA fragments were clearly visible in 2% agarose gel and showed apoptotic cell death induced by proton beam. (C) At 24 h after irradiated with proton beam (100 Gy), LLC cells were fixed with ethanol and stained with FITC-Annexin V to detect cell death phenomena. Y axis shows PI labeled population and X axis shows FITC-labeled Annexin-V positive cells. Proton beam increased early apoptosis as well as late apoptosis and necrotic phase.

Proton beam induced apoptosis via activation of caspases

To investigate the mechanisms by which proton beam-irradiated cancer cells induce apoptotic cell death, we performed western blot analysis with antibodies against apoptosis-related proteins. PARP protein was cleaved into small molecular weight forms by proton beam irradiation both in LLC and HepG2 cells (Figure 4A and B). Procaspase-9 was decreased by about 2.5 fold in LLC and cleaved caspase-3 was increased by 3.5 fold in proton beam-treated LLC cells (Figure 4A). In HepG2 cells procaspase-9 was decreased significantly (5 fold) and cleaved caspase-3 was increased, indicating caspase-9 and -3 were activated when treated with proton beam (Figure 4B). However, caspase-8 was not changed significantly either in LLC (0.94 fold) or HepG2 (1.13 fold) cells. Procaspase-7 was detected in HepG2 cells but it was not changed by proton irradiation. The cleaved caspase-9, not caspase-8 might activate procaspase-3 into a cleaved form in proton-irradiated cells in these two cell lines. Both in HepG2 and LLC cells, proton beam decreased XIAP (inhibitor of apoptosis protein), consistent with the result of increased active caspase-3 because XIAP is known to exert an anti-apoptotic effect by interfering with the processing and activities of caspase-3 (Deveraux and Reed, 1999). Significant decrease of Bcl-2 and increase of Bax in proton-treated LLC and HepG2 cells were found (Figure 4A and B), suggesting that mitochondrial dysfunction was involved in the apoptosis in both cell lines. Gamma-ray increased PARP-1 cleavage and caspase-3 activation as well as caspase-7 cleavage was observed significantly in Molt-4 leukemia cells. It was interesting that both Bcl-2 and Bax were down-regulated by γ-ray (Figure 4C). But the fact that different sets of caspases were activated by γ-ray suggests specific caspases activation cascades are involved in different radiation therapeutics.

Figure 4.

Western blot analysis for apoptosis-related protein in proton-beam or gamma-ray irradiated cancer cells. (A) LLC cells were irradiated with proton beam (100 Gy) and one day after cells were collected and lysed for western blot with antibodies against apoptosis related proteins. (B) HepG2 cells were collected on a day after the proton beam irradiation (100 Gy). Western blot analysis showed the expression of various apoptotic proteins. (C) Molt-4 cells were irradiated with γ-ray (100 Gy) and collected protein lysate one day after. Gamma ray-induced apoptotic proteins in Molt-4 were examined by Western blot analysis. All Western blot data was analyzed from the two or three independent experiments and obtained the fold induction for control band density with ImageJ analysis followed by statistical test at P < 0.05.

Proton beam increased ROS level and activated p38 MAPK and JNK

To determine whether the apoptosis and caspase activation induced by proton beam is mediated by the increase of ROS, we measured the ROS levels after 4 h of proton beam irradiation both in HepG2 and LLC cells. Intracellular ROS production was measured using the oxidant-sensitive fluorescent probe DCFH-DA. Proton irradiation increased ROS generation 1.5 to 1.8 fold relative to control cells (Figure 5A). For a long-term incubation of cells followed by irradiation we did not detect an increase of ROS levels, suggesting that the intracellular ROS generation by the proton beam is quite dynamic and probably could be abolished by the intracellular defense mechanism as the time passed. But the generated ROS at some peak point may cause initiation of intracellular apoptosis signal. By N-acetyl cysteine, a ROS scavenger treated prior to proton beam irradiation, the cell death induced by proton beam was recovered (Figure 5B), indicating ROS is a key mediator to induce tumor cell death by proton beam.

Figure 5.

ROS-mediated apoptosis in proton beam-irradiated HepG2 cells. (A) Level of ROS in LLC and HepG2 cells measured by DCFDA. *P < 0.01 versus control in each cell line (no treatment of proton). (B) When NAC (5 mM) was treated 4 h before proton irradiation, the cell death induced by proton beam (100 Gy) was restored both in LLC and HepG2 cells. *P < 0.01 versus only proton treated one in each cell line. (C) Caspase-3 activities were measured and compared with control non-treated cells after the irradiation of proton beam (100 Gy) in LLC and HepG2 cells. *P < 0.01 between control and only proton treated one in each cell line. **P < 0.01 between only proton treated and NAC pretreated one in each cell line. (D) HepG2 cells were treated with proton beam 100 Gy and for the detection of phosphorylation of MAPKs and Akt, cells were collected at 1 h after irradiation and the kinase levels were detected by Western analysis. (E) HepG2 cells were transfected with DN-p38 MAPK or DN-JNK and on next day irradiated with proton beam (10 or 50 Gy). After 24 h, cell viability was determined with MTT assay. (A-C, E) All data were shown as a fold induction of control cell viability. The data were Mean ± SD (n = 5). All experiments were performed in duplicate. *P < 0.01 versus control in each DN transfectant.

To verify whether the caspase activation induced by proton beam irradiation is mediated by ROS, caspase activity was investigated by the substrate-enzyme reaction in the absence or presence of ROS scavenger. Twenty four h after irradiation cell lysates were collected, added with caspase substrate Ac-DEVE-pNA and checked the enzyme activity. The activity of caspase-3 was higher than the control both in LLC and HepG2 cells. Proton beam significantly increased caspase activity but the NAC treatment significantly diminished caspase activity in both cells (Figure 5C). These results addressed that proton beam induced apoptosis in these tumor cells via the activation of caspases and ROS.

Next, to investigate ROS-mediated signaling pathway, we checked the activation of MAPKs by western blot analysis. Phospho-p38 MAPK and phospho-JNK were increased but phospho-Akt and -ERK MAPK were decreased by the treatment of proton beam, indicating activation of MAPKs and inactivation of survival kinases are both involved in proton-induced apoptotic cancer cell death pathway (Figure 5D). In order to verify the involvement of these two kinds of stress-induced MAPKs in proton beam-induced apoptosis, we transfected cells with dominant negative (DN) mutants of p38 and JNK MAPKs and examined cell survival rate. DN-p38 and -JNK mutant transfected cells became resistant to the treatment of proton beam (Figure 5E). These results suggest that p38 and JNK pathways might cooperate in apoptotic signaling pathway and might be mediated by ROS induced by proton beam irradiation.

Taken together, we concluded that proton beam activated apoptosis in LLC and HepG2 cells and increased RBE values relative to γ-ray vary depending on the cancer cell types. And the apoptosis induced by proton beam might be regulated by the generation of ROS and activation of caspase-3.

Discussion

Here we investigated the cellular and molecular mechanism by which proton beam induced tumor cell apoptosis. This phenomenon was observed at SOBP irradiation method in HepG2, LLC as well as in Molt-4. Various kinds of tumor patients have been tried with proton therapy so far. Typical tumor types being treated with proton beam are melanoma, lung cancer, ocular tumor, and breast cancer and almost any other solid tumors (Levin et al., 2005; MacDonald et al., 2006). Especially hepatoma and lung cancer patient have potential therapeutic trials and results (Bjelkengren and Glimelius 2005; Mayahara et al., 2005; Hashimoto et al., 2006). Recent boom to use proton beam for tumor radiation therapy is due to spare healthy tissues relatively safe than tumor tissues. Our experiment used in vitro cell culture systems and determined the RBE of proton beam relative to γ-ray at the SOBP on which cells were plated and the cell death mechanisms induced by proton beam irradiation. In our in vitro system proton beam at relatively high doses with low energy (35 Mev) was used because these doses were effective within 24 h on cancer cell death. Prolonged incubation until 48 h or 72 h after irradiation showed more increased death rate than those at 24 h (Figure 2, 72 h). Long-term effect with colony formation assay for 11 days with single treatment also showed low dose were effective. In our experimental system, LLC cells were susceptible to proton beam above 100 Gy with SOBP and HepG2 hepatoma cells were also responsive to proton therapy above 100 Gy showing around 70-80% cell survival with SOBP (Figure 2A), consistent with previous clinical data showing hepatoma and lung cancer susceptible to proton (Bjelkengren and Glimelius 2005; Mayahara et al., 2005; Hashimoto et al., 2006). However, there is few report that leukemia patient received proton therapy and succeeded. Our result with leukemia cell line showed proton therapy had lower RBE values for cell death in vitro (Figure 2B). RBE values for hepatoma and lung cancer cells were above 1.1 but for leukemia cells were 0.7 at 11 days after irradiation. These results clearly showed that proton and gamma irradiation have different sensitivities to induce cell death depending on cancer cell types. Different sensitivity to proton beam is probably due to the different genetic background of p53, because p53 is mutated in Molt-4 cells whereas not in LLC and HepG2 cells. Our unpublished data in cells with deletion mutant p53 also support that p53 wild type is critical to induce cell death by the treatment of proton beam. It is reported that γ ray induced Molt-4 cell death is caused by p53 accumulation and phosphorylation at serin-392 (Szkanderova et al., 2003). Even Molt-4 cell has a mutation of p53 at glycine-248, it does not seem to be a critical region to induce cell death by γ-ray. It is also investigated that the sensitivity to γ-ray in cancer cell death is rather irrespective of p53 status (Christophorou et al., 2005) and thus suggested that diverse cell death mechanisms might be involved in γ-ray-induced cell death in a way of p53 dependency (Soderlund et al., 2005; Rashi-Elkeles et al., 2006).

A recent report suggests that cell death induced by proton is apoptosis rather necrosis or autophagy (Di Pietro et al., 2006). In our result, cell death by proton is clearly apoptotic, i.e., nuclear DNA fragments and segregating pattern of nucleus shown in Figure 3A. Tiny DNA fragments confirmed by DNA agarose gel electrophoresis were observed in proton-irradiated HepG2 cells whereas proton insensitive Molt4 cells did not show any fragmented DNA (Figure 3B). Annexin-V staining also demonstrates apoptotic cell death was induced by proton (Figure 3C). A few reports suggest that cell cycle arrest on G2/M phase by proton beam is one possible mechanism to induce apoptosis in melanoma cells (Ristic-Fira et al., 2001; Petrovic et al., 2006). And we found that the mechanism to induce cell death by proton beam in HepG2 and LLC cells may be dependent on caspase-3 activation. For the activation of caspase-3, caspase-9 seemed to be activated in LLC and HepG2, because procaspase-9 was decreased (Figure 4A) but neither caspase-8 nor caspase-7 (Figure 4A and B). Decreased expression of XIAP may be involved in the activation of caspases (Figure 4), because IAPs prohibit the caspase-3 activation by caspase-9. Bax and p53 was upregulated by proton beam (data not shown), suggesting that p53 increased cell death through the transcription-dependent apoptotic mechanism in LLC cells. Usually p53 activates caspases by the mitochondrial pathways (Schuler and Green, 2001; Kadenbach et al., 2004; Gong et al., 2006) or alternatively by generation of ROS (Polyak et al., 1997; Li et al., 1999). From our results, proton beam activates caspase-3 as well as increased oxidative stress. Thus, in our experimental condition, proton beam activates caspases and increases ROS generation through p53. Increased ROS may activate p53 and vice versa in a feed-back activated manner. Actually we found that proton beam-induced apoptosis occurs in a p53-dependent mechanism and ROS was generated in p53 deleted cancer cells explaining that ROS is a general mediator.

Gamma irradiation is a well known ROS generator to induce cancer cell death, especially suspended cells, such as leukemia cells (Lee and Park, 2005). The oxidative stress induced by γ-ray further increases p53 (El-Assaad et al., 2003) and down-regulates Bcl-2 (Li et al., 2004), consisting with our results (Figure 4C). It has been reported that ROS is generated from the alveolar macrophages in rat by proton beams (Tasat et al., 2003). In this study, we investigated proton beam with single treatment induced tumor cell death cultivated as a monolayer in vitro condition and a possible mechanism by which proton beam induces tumor cell apoptosis. ROS promote apoptosis by stimulating pro-apoptotic signaling molecules such as ASK1, JNK and p38 MAPK (Benhar et al., 2001; Jr Davis et al., 2001; Tobiume et al., 2001; Kim et al., 2004). Activation of JNK and p38 MAPK in proton likely mediates apoptosis induced by proton. Even there is no direct evidence the activation of p38 MAPK is caused by DNA damage, p38 MAPK is a sensor of ROS to inhibit their accumulation and enhanced tumorigenesis (Dolado et al., 2007). Thus it is speculated that ROS might be a main regulator of p53 activation through JNK pathway and to activate p38 MAPK, which are cooperative but distinct pathway to trigger cell death program in cancer cells (Figure 5D). Phospho-Akt was decreased by proton (Figure 5D), consistent with the report that activation of Akt demonstrates more resistant against apoptosis (Sah et al., 2006). Because ERK activation is necessary for cell cycle entry and counteracts against apoptosis (Robertson, 2005), the dramatic decrease of phospho-ERK and -Akt by proton irradiation is assumed to contribute to induce cancer cell apoptosis.

In conclusion, proton beam with a single treatment with low or high dose induced apoptotic cell death depending on the specific cancer cell types. And proton induced ROS generation in the cells to activate caspases and stress-induced MAPKs. Further experiments for best controlled various tumor cell death induced by proton beam should be performed and for possible another mechanisms to induce cancer cell apoptosis may provide the methodology to adequate cancer therapy in clinical applications.

Acknowledgments

This research work has been performed under the User Program of PEFP (Proton Engineering Frontier Project), as a part of the 21C Frontier R&D Program supported by the MOST (Ministry of Science and Technology) and Kyungpook National University Research Fund, 2005. We thank Dr. Jeonghee Yang for critical review of the manuscript and Dr. Kye-Ryung Kim for continuing support and encouragement.

Abbreviations

- AIF

apoptosis inducing factor

- CCK-8

cell counting kit-8

- DAPI

4'-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- DN

dominant negative

- IAP

inhibitors of apoptosis

- LLC

Lewis lung carcinoma

- NAC

N-acetyl cysteine

- PARP-1

poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1

- RBE

relative biological effectiveness

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SOBP

spread out Bragg peak

References

- 1.Belli M, Cherunbiti R, Finotto S, Moschini G, Sapora O, Simone G, Tabocchini MA. RBE-LET relationship for survival of V79 cells irradiated with low energy protons. Int J Rad Biol. 1989;55:93–104. doi: 10.1080/09553008914550101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belli M, Cera F, Cherubini R, Dalla Vecchia M, Haque AM, Ianzini F, Moschini G, Sapora O, Simone G, Tabocchini MA, Tiveron P. RBE-LET relationship for cell inactivation and mutation induced by low energy protons in V79 cells: further results at the LNL facility. Int J Rad Biol. 1998;74:501–509. doi: 10.1080/095530098141375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belli M, Bettega D, Calzolari P, Cera F, Cherubini R, Dalla Vecchia M, Durante M, Favaretto S, Gialanella G, Grossi G, Marchesini R, Moschini G, Piazzola A, Poli G, Pugliese M, Sapora O, Scampoli P, Simone G, Sorrentino E, Tabocchini MA, Tallone L, Tiveron P. Inactivation of human normal and tumour cells irradiated with low energy protons. Int J Radiat Biol. 2000;76:831–839. doi: 10.1080/09553000050028995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benhar M, Dalyot I, Engelberg D, Levitzki A. Enhanced ROS production in oncogenically transformed cells potentiates c-Jun N-terminal kinase and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation and sensitization to genotoxic stress. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:6913–6926. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.20.6913-6926.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benhar M, Engelberg D, Levitzki A. ROS, stress-activated kinases and stress signaling in cancer. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:420–425. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bettega D, Calzolari P, Chauvel P, Courdi A, Herault J, Iborra N, Marchesini R, Massariello P, Poli GL, Tallone L. Radiobiological studies on the 65 MeV therapeutic proton beam at Nice using human tumour cells. Int J Radiat Biol. 2000;76:1297–1303. doi: 10.1080/09553000050151565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bjelkengren G, Glimelius B. The potential of proton beam radiation therapy in lung cancer (including mesothelioma) Acta Oncol. 2005;44:881–883. doi: 10.1080/02841860500355975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bubici C, Papa S, Dean K, Franzoso G. Mutual cross-talk between reactive oxygen species and nuclear factor-kappa B: molecular basis and biological significance. Oncogene. 2006;25:6731–6748. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christophorou MA, Martin-Zanca D, Soucek L, Lawlor ER, Brown-Swigart L, Verschuren EW, Evan GI. Temporal dissection of p53 function in vitro and in vivo. Nat Genet. 2005;37:718–726. doi: 10.1038/ng1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cregan SP, Dawson VL, Slack RS. Role of AIF in caspase-dependent and caspase-independent cell death. Oncogene. 2004;23:2785–2796. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deveraux QL, Reed JC. IAP family proteins-suppressors of apoptosis. Genes Dev. 1999;13:239–252. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.3.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di Pietro C, Piro S, Tabbi G, Ragusa M, Di Pietro V, Zimmitti V, Cuda F, Anello M, Consoli U, Salinaro ET, Caruso M, Vancheri C, Crimi N, Sabini MG, Cirrone GA, Raffaele L, Privitera G, Pulvirenti A, Giugno R, Ferro A, Cuttone G, Lo Nigro S, Purrello R, Purrello F, Purrello M. Cellular and molecular effects of protons: Apoptosis induction and potential implications for cancer therapy. Apoptosis. 2006;11:57–66. doi: 10.1007/s10495-005-3346-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dolado I, Swat A, Ajenjo N, De Vita G, Cuadrado A, Nebreda AR. p38alpha MAP kinase as a sensor of reactive oxygen species in tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:191–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El-Assaad W, Kozhaya L, Araysi S, Panjarian S, Bitar FF, Baz E, El-Sabban ME, Dbaibo GS. Ceramide and glutathione define two independently regulated pathways of cell death initiated by p53 in Molt-4 leukaemia cells. Biochem J. 2003;376:725–732. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Engel RH, Evens AM. Oxidative stress and apoptosis: a new treatment paradigm in cancer. Front Biosci. 2006;1:300–312. doi: 10.2741/1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fuchs SY, Adler V, Pincus MR, Ronai Z. MEKK1/JNK signaling stabilizes and activates p53. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:10541–10546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gong X, Wang M, Tashiro S, Onodera S, Ikejima T. Involvement of JNK-initiated p53 accumulation and phosphorylation of p53 in pseudolaric acid B induced cell death. Exp Mol Med. 2006;38:428–434. doi: 10.1038/emm.2006.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davis W, Jr, Ronai Z, Tew KD. Cellular thiols and reactive oxygen species in drug-induced apoptosis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;296:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hashimoto T, Tokuuye K, Fukumitsu N, Igaki H, Hata M, Kagei K, Sugahara S, Ohara K, Matsuzaki Y, Akine Y. Repeated proton therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65:196–202. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Igney FH, Krammer PH. Death and anti-death: tumour resistance to apoptosis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:277–288. doi: 10.1038/nrc776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang ZY, Hunt JV, Wolff SP. Ferrous ion oxidation in the presence of xylenol orange for detection of lipid hydroperoxide in low density lipoprotein. Anal Biochem. 1992;202:384–389. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(92)90122-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kadenbach B, Arnold S, Lee I, Huttemann M. The possible role of cytochrome c oxidase in stress-induced apoptosis and degenerative diseases. Biochem Biophys Acta. 2004;1655:400–408. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2003.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim YS, Jhon DY, Lee KY. Involvement of ROS and JNK1 in selenite-induced apoptosis in Chang liver cells. Exp Mol Med. 2004;36:157–164. doi: 10.1038/emm.2004.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee JH, Park JW. The effect of alpha-phenyl-N-t-butylnitrone on ionizing radiation-induced apoptosis in U937 cells. Free Radic Res. 2005;39:1325–1333. doi: 10.1080/10715760500217215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levin WP, Kooy H, Loeffler JS, DeLaney TF. Proton beam therapy. Br J Cancer. 2005;93:849–854. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li D, Ueta E, Kimura T, Yamamoto T, Osaki T. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) control the expression of Bcl-2 family proteins by regulating their phosphorylation and ubiquitination. Cancer Sci. 2004;95:644–650. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb03323.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li PF, Dietz R, von Harsdorf R. p53 regulates mitochondrial membrane potential through reactive oxygen species and induces cytochrome c-independent apoptosis blocked by Bcl-2. EMBO J. 1999;18:6027–6036. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.21.6027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacDonald SM, DeLaney TF, Loeffler JS. Proton beam radiation therapy. Cancer Invest. 2006;24:199–208. doi: 10.1080/07357900500524751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mayahara H, Oda Y, Kawaguchi A, Kagawa K, Murakami M, Hishikawa Y, Igaki H, Tokuuuye K, Abe M. A case of hepatocellular carcinoma initially treated by carbon ions, followed by protons for marginal recurrence with portal thrombus. Radiat Med. 2005;23:513–519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mishra KP. Cell membrane oxidative damage induced by gamma-radiation and apoptotic sensitivity. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol. 2004;23:61–66. doi: 10.1615/jenvpathtoxoncol.v23.i1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paganetti H, Niemierko A, Ancukiewicz M, Gerweck LE, Goitein M, Loeffler JS, Suit HD. Relative biological effectiveness (RBE) values for proton beam therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;53:407–421. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)02754-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Petrovic I, Ristic-Fira A, Todorovic D, Valastro L, Cirrone P, Cuttone G. Radiobiological analysis of human melanoma cells on the 62 MeV CATANA proton beam. Int J Radiat Biol. 2006;82:251–265. doi: 10.1080/09553000600669859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Polyak K, Xia Y, Zweier JL, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Model for p53-induced apoptosis. Nature. 1997;389:300–305. doi: 10.1038/38525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rashi-Elkeles S, Elkon R, Weizman N, Linhart C, Amariglio N, Sternberg G, Rechavi G, Barzilai A, Shamir R, Shiloh Y. Parallel induction of ATM-dependent pro- and antiapoptotic signals in response to ionizing radiation in murine lymphoid tissue. Oncogene. 2006;25:1584–1592. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ristic-Fira A, Nikolic D, Petrovic I, Ruzdijic S, Raffaele L, Sabini MG, Cirrone GA, Cuttone G, Farruggia G, Masotti L, Kanazir DT. The late effects of proton irradiation on cell growth, cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in a human melanoma cell line. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2001;20:135–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robertson GP. Functional and therapeutic significance of Akt deregulation in malignant melanoma. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2005;24:273–285. doi: 10.1007/s10555-005-1577-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sah NK, Munshi A, Hobbs M, Carter BZ, Andreeff M, Meyn RE. Effect of downregulation of survivin expression on radiosensitivity of human epidermoid carcinoma cells. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;66:852–859. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Samuni AM, Kasid U, Chuang EY, Suy S, Degraff W, Krishna MC, Russo A, Mitchell JB. Effects of hypoxia on radiation-responsive stress-activated protein kinase, p53, and caspase 3 signals in TK6 human lymphoblastoid cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:579–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schuler M, Green DR. Mechanisms of p53-dependent apoptosis. Biochem Soc Trans. 2001;29:684–688. doi: 10.1042/0300-5127:0290684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Soderlund K, Perez-Tenorio G, Stal O. Activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway prevents radiation-induced apoptosis in breast cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2005;26:25–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Szkanderova S, Vavrova S, Rezacova M, Vokurkova D, Pavlova S, Smardova J, Stulik J. Gamma irradiation results in phosphorylation of p53 at serine-392 in human T-lymphocyte leukaemia cell line MOLT-4. Folia Biol (Praha) 2003;49:191–196. doi: 10.14712/fb2003049050191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tasat DR, Mancuso R, Molinari BL, Saint-Martin G, Pérez de la Hoz A, Bernaola OA, Kreiner AJ, Schuff JA, Palmieri M, Mazal A, Stoliar P, Burlón A, Davidson M, Davidson J, Debray ME, Kesque JM, Somacal H, Naab G, Ozafrán MJ, Vazquez ME. Low energy proton irradiation effects on alveolar macrophages from young and aged rats. Cell Mol Biol. 2003;49:OL387–OL392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tobiume K, Matsuzawa A, Takahashi T, Nishitoh H, Morita K, Takeda K, Minowa O, Miyazono K, Noda T, Ichijo H. ASK1 is required for sustained activations of JNK/p38 MAP kinases and apoptosis. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:222–228. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsujimoto Y. Cell death regulation by the Bcl-2 protein family in the mitochondria. J Cell Physiol. 2003;195:158–167. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ueda S, Masutani H, Nakamura H, Tanaka T, Ueno M, Yodoi J. Redox control of cell death. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2002;4:405–414. doi: 10.1089/15230860260196209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]