Abstract

Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) is known to modulate bone metabolism, including bone formation and resorption. Because cartilage serves as a template for endochondral bone formation and because cartilage development is initiated by the differentiation of mesenchymal cells into chondrocytes (Ahrens et al., 1977; Sandell and Adler, 1999; Solursh, 1989), it is of interest to know whether COX-2 expression affect chondrocyte differentiation. Therefore, we investigated the effects of COX-2 protein on differentiation in rabbit articular chondrocyte and chick limb bud mesenchymal cells. Overexpression of COX-2 protein was induced by the COX-2 cDNA transfection. Ectopic expression of COX-2 was sufficient to causes dedifferentiation in articular chondrocytes as determined by the expression of type II collagen via Alcian blue staining and Western blot. Also, COX-2 overexpression caused suppression of SOX-9 expression, a major transcription factor that regulates type II collagen expression, as indicated by the Western blot and RT-PCR. We further examined ectopic expression of COX-2 in chondrifying mesenchymal cells. As expected, COX-2 cDNA transfection blocked cartilage nodule formation as determined by Alcian blue staining. Our results collectively suggest that COX-2 overexpression causes dedifferentiation in articular chondrocytes and inhibits chondrogenic differentiation of mesenchymal cells.

Keywords: chondrocytes, cyclooxygenase 2, cell dedifferentiation, cell differentiation, collagen type II, mesenchymal cells

Introduction

Chondrocytes in cartilage are differentiated from mesenchymal cells during embryonic development. Differentiated chondrocytes, which are the only cell type found in normal mature cartilage, synthesize sufficient amounts of cartilage-specific extracellular matrix (ECM) to maintain matrix integrity. This homeostasis is destroyed in degenerative diseases, such as osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis (Sandell and Aigner, 2001). Arthritis is characterized by structural and biochemical changes in chondrocytes and cartilage, including degradation of cartilage matrix, insufficient synthesis of ECM because of loss of chondrocyte phenotype. However, the differentiated phenotype is unstable both in vivo and in vitro and thus lost by a process designated "dedifferentiation" upon exposure of cells to IL-1β (Goldring et al., 1994; Demoor-Fossard et al., 1998), nitric oxide (Amin and Abramson, 1998), or retinoic acid (Cash et al., 1997; Weston et al., 2000) and during serial monolayer culture (Lefebvre et al., 1990; Yoon et al., 2002). However, little is known about dedifferentiation in articular chondrocytes.

COX is known to exist in two isoforms, COX-1 and COX-2. And two COXs are identified similar sequence (Smith et al., 2000). COX-1 is considered a constitutive enzyme, being found in most mammalian cells (Dubois et al., 1998). COX-2, on the other hand, is undetectable in most normal tissues (Wu, 1995). COX-2 is an inducible enzyme, becoming abundant in activated macrophages and other cells at sites of inflammation by various stimuli including cytokines. Expression of COX-2 increased PGE2 (Namkoong et al., 2005). PGE2 induced various inflammation reactions (Smith et al., 1996).

Mice lacking COX-2 but not COX-1 expression display reduced bone resorption in response to parathyroid hormone (PTH) or 1,25-hydroxyl vitamin D3 (Okada et al., 2000). In addition to bone resorption, COX-2 may also have a role in bone formation. Systemic or local injection of PGE2 stimulates bone formation (Weinreb et al., 1997; Suponitzky and Weinreb, 1998). Increased lamellar bone formation in response to mechanical strain is mediated by COX-2 (Duncan and Turner, 1995; Forwood, 1996).

The crucial events in adult bone formation are the recruitment, proliferation, and differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells with endochondral and intramembranous bone formation at the injury site (Bruder et al., 1994). In endochondral ossification, mesenchymal cells first differentiate into chondrocytes, which subsequently undergo terminal differentiation and apoptosis, leading to calcification of the matrix.

Based on these findings, we investigated the effects of COX-2 in the dedifferentiation of articular chondrocytes and chondrogenesis. Here, we suggest that COX-2 overexpression might be responsible for dedifferentiation of articular chondrocytes and chondrogenesis of mesenchymal cells.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

As described previously (Oh et al., 2000; Yoon et al., 2000), mesenchymal cells, which were isolated from chicken embryo wing buds, were grown in micromass culture to induce chondrogenesis. Chondrifying mesenchymal cells were transfected with COX-2 cDNA. Articular chondrocytes were isolated from cartilage slices of 2-week-old New Zealand white rabbits by enzymatic digestion as described previously (Yoon et al., 2002). Cartilage slices were dissociated enzymatically for 6 h in 0.2% collagenase type II (381 U/mg solid, Sigma) in DMEM (Gibco-BRL, Gaithersburg, MD). Individual cells were suspended in DMEM supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine-calf serum, 50 µg/ml streptomycin, and 50 units/ml penicillin, after which and they were then plated on culture dishes at a density of 5 × 104 cells/cm2. The medium was changed every 2 days after seeding, and cells reached confluence in approximately 5 days. Differentiation status of articular chondrocytes was determined by examining the accumulation of sulfated glycosaminoglycan with Alcian Blue staining or expression of type II collagen was detected using antibodies purchased from Chemicon (Temecula, CA) by Western blot analysis as described previously (Yoon et al., 2002).

Immunoblot analysis

Whole cell lysates were prepared by extracting proteins using a buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, and 0.1% SDS, supplemented with protease inhibitors [10 µg/ml leupeptin, 10 µg/ml pepstatin A, 10 µg/ml aprotinin and 1 mM of 4-(2-aminoethyl) benzenesulfonyl fluoride] and phosphatase inhibitors (1 mM NaF and 1 mM Na3VO4). The proteins were size-fractionated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The nitrocellulose sheet was then blocked with 3% non-fat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline. COX-2 was detected using antibody purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI), and Sox-9 and ERK-2 were detected using antibodies purchased from Santa Cruz Biotech. (Santa Cruz, CA). Blots were developed using a peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody and visualized with an ECL system.

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence microscopy

Wing buds of chicken embryos and spots of micromass culture were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 40 min at room temperature. The cells were stained by standard procedures using Alcian blue. Rabbit joint cartilage explants or arthritic cartilage were in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 24 h at 4℃, washed with PBS, dehydrated with graded ethanol, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at 4 µm thickness. The sections were stained by standard procedures using Alcian blue or antibody against type II collagen and visualized by developing with a kit purchased from DAKO (Carpinteria, CA). Expression and distribution of type II collagen and COX-2 in rabbit articular chondrocytes were determined by indirect immunofluorescence microscopy, as described previously (Ryu et al., 2002). Briefly, chondrocytes were fixed with 3.5% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min at room temperature. The cells were permeabilized and blocked with 0.1% Triton X-100 and 5% FCS in PBS for 30 min. The fixed cells were washed and incubated for 1 h with antibody (10 µg/ml) against type II collagen or COX-2. The cells were washed, incubated with rhodamine-conjugated secondary antibodies for 30 min, and observed under a fluorescence microscope.

Transfection

To introduce cDNA for COX-2, mesenchymals cells and articular chondrocytes were transfected with plasmid containing COX-2 cDNA. Transfection of the expression vector was performed as described previously (Ryu et al., 2002). The COX-2 (1 µg) was introduced to cells using METAFECTENE (Biontex) using the procedure recommended by the manufacturer. The transfected cells, which were cultured in complete medium for 48 h, were used for further assay as indicated in each experiment

RT-PCR

Primary cultured chondrocytes were transfected with COX-2 cDNA. Total RNA was isolated from the cell and reverse transcribed with Maxime RT-PCR PreMix kit (INTRON Biotechnology). The following primers (based on the sequences of the rabbit type II collagen and on the sequences of the human SOX-9 genes) and conditions were used in PCR: Type II collagen (370 bp product, annealing temperature 45℃, 30 Cycle), sense 5'-GACCCCATGCAGTACATGCG-3'; antisense 5'-AGCCGCCATTGATGGTCTCC-3', SOX-9 (386 bp product, annealing temperature 45℃, 21 Cycle), sense 5'-GCGCGTGCACAAGAAGGACCACCCGGATTACAAGTA-3'; antisense 5'-CGAAGGTCTCGATGTTGGAGATGACGTCGCTGCTCAGCTC-3'. GAPDH was amplified for control and normalization purposes using the following primers and conditions;( 299 bp product, annealing temperature 45℃, 30 Cycle), sense 5'-TCACCATCTTCCAGGAGCGA-3'; antisense 5'-CACAATGCCGAAGTGGTCGT-3'. Sequencing of the PCR products for rabbit SOX-9 showed that these gene fragment was 93% homologous respectively to the corresponding human genes.

Knockdown of COX-2 by siRNA

Rabbit COX-2 was cloned from chondrocytes (GeneBankTM accession number NM017237), and the following siRNA sequences were selected using siRNA WizardTM (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA): 5'-UGAUAGAGUGUCUUCAAUUCAGAGC-3' (no.1), 5'-CCUCUGAAUUCAAGACACUCUAUCA-3' (no. 2), 5'-AUGUCAUCUAGUCUGGAGUGGGAGG-3' (no. 3). Cells were transfected with the siRNA (100 pM) using Metafectene. Three of the tested siRNAs caused effective knockdown of COX-2.

Data analyses and statistics

The results are expressed as the means ± S.E. values calculated from the specified number of determinations. A Student's t-test was used to compare individual treatments with their respective control values. A probability of P < 0.05 was taken as denoting a significant difference.

Results

Ectopic expression of COX-2 induces dedifferentiation of rabbit articular chondrocytes

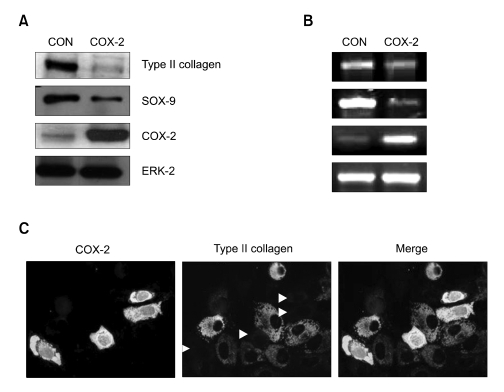

To examine the effects of the expression of COX-2 as an central enzyme in the inflammatory cascade on articular cartilage chondrocyte differentiation, the protein was overexpressed by the COX-2 cDNA transfection. Ectopic expression of COX-2 inhibited type II collagen, a marker for differentiation of articular chondrocytes (Yoon et al., 2002) as determined by immunoblotting and RT-PCR, respectively (Figure 1A, B). Consistent with the inhibition of type II collagen expression, levels of SOX-9, a potent activator of the chondrocyte-specific enhancer of the pro alpha 1 (II) collagen gene (Lefebvre et al., 1997; DeLise et al., 2000) was decreased by the COX-2 overexpression (Figure 1A, B). To directly determine whether COX-2 expression is involved in the regulation of chondrocyte dedifferentiation, chondrocytes were transfected with COX-2 cDNA. Immunofluorescence double staining of COX-2 and type II collagen in chondrocytes transfected with COX-2 cDNA indicated that cells highly expressing COX-2 are negative for type II collagen staining (indicated by white arrow head), whereas cell do not express COX-2 are positive for type II collagen staining (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Ectopic expression of COX-2 decreases type II collagen and SOX-9 expression in articular chondrocytes. Chondrocytes were transfected with empty vector (CON) or vector containing wild type COX-2 (COX-2-transfected). Expression of type II collagen, SOX-9 and COX-2 was detected using Western blot analysis (A) and RT-PCR (B), respectively. ERK-2 was used as loading controls. COX-2 and type II collagen were double stained in COX-2-transfected cells using anti-COX-2 and anti-type II collagen antibodies, and photographs were taken with an immunofluorescence microscope (C). The data represent the results of a typical experiment conducted at least three times with similar results.

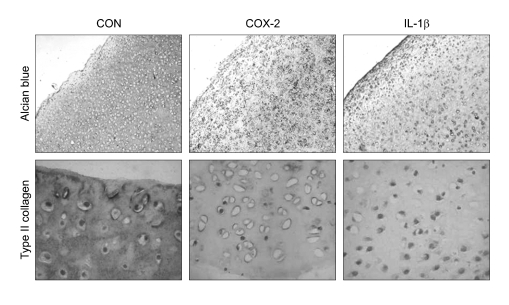

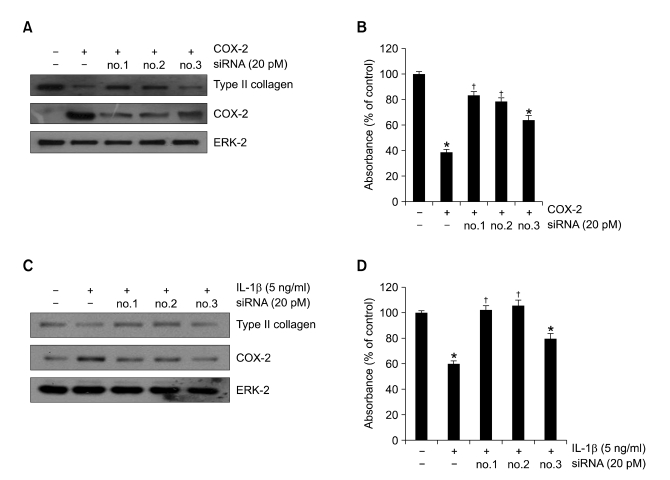

To confirm the effects of COX-2 expression on chondrocyte differentiation, we used cartilage explant cultures which were transfected with COX-2 cDNA or treated with 5 ng/ml IL-1β for 24 h. Our previous data demonstrated that IL-1β induced COX-2 expression and also caused dedifferentiation of articular chondrocytes (Kim et al., 2003). Ectopic expression of COX-2 or IL-1β caused a dramatic loss of sulfated proteoglycan and type II collagen as determined Alcian blue staining and immunohistochemical staining, respectively (Figure 2). The role of COX-2 in the regulation of type II collagen expression was further characterized by knock-down of COX-2 using siRNAs. Three examined siRNAs (no. 1, no. 2, no. 3) effectively inhibited the COX-2 overexpression by COX-2 transfection or IL-1β and resulted in a concomitant recovery of type II collagen, respectively (Figure 3A and C). Similarly, knock-down of COX-2 using the three siRNAs blocked COX-2-transfected or IL-1β-stimulated dedifferentiation as indicated sulfated proteoglycan accumulation (Figure 3B and D).Taken together, these results indicate that ectopic expression of COX-2 appears to be sufficient to induce dedifferentiation of articular chondrocytes.

Figure 2.

Ectopic expression of COX-2 causes dedifferentiation of articular chondrocytes. Cartilage explants were transfected with empty vector (untreated) or transfected with wild type COX-2 (COX-2-transfected) or treated with 5 ng/ml IL-1β (IL-1β) for 24 h. Type II collagen and proteoglycan were detected by immunohistochemical staining (× 400) and Alcian blue staining (× 200), respectively. The data represent results of typical experiment conducted at least four times.

Figure 3.

Knockdown of COX-2 rescues COX-2-induced dedifferentiation. Chondrocytes were transfected with empty vector (-) or three different constructs of rabbit COX-2 siRNA (no. 1, no. 2, and no. 3). Following a 4 h incubation, the cells were untransfected (-) or transfected with wild type COX-2 (COX-2-transfected). Transfected cells were cultured in complete medium for 24 h. Expression levels of type II collagen and COX-2 were determined by Western blot analysis (A) while accumulation of sulfated glycosaminoglycan was quantified by Alcian blue staining (B). After 4 h of siRNA transfection, the cells were untreated (-) or treated (+) with 5 ng/ml IL-1β for an additional 24 h. Expression levels of type II collagen and COX-2 were determined by Western blot analysis (C). ERK-2 was analyzed as loading controls. Accumulation of sulfated glycosaminoglycan was quantified by Alcian blue staining (D).The data represent the results of a typical experiment conducted at least three times with similar results.

Ectopic expression of COX-2 inhibits chondrogenesis of mesenchymal cells

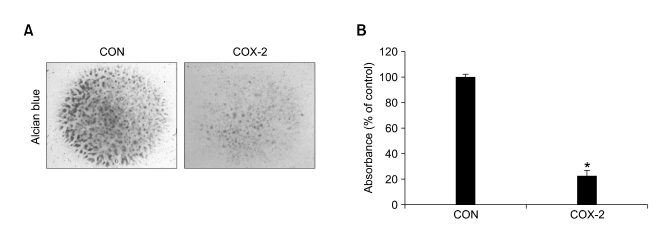

Micromass culture of dissociated chick limb bud mesenchymal cells is frequently used as a model system to study chondrogenesis (Ahrens et al., 1977; Sandell and Adler, 1999). Chondrogenic differentiation of mesenchymal cells is accompanied by morphological changes such as precartilage condensation and cartilage nodule formation. We further examined whether ectopic expression of COX-2 regulated chondrogenesis of mesenchymal cells. Precartilage condensation was verified by staining the cells with peanut agglutinin which specifically marks precartilage condensation. As expected, COX-2 cDNA transfection did not affect precartilage condensation as determined by peanut agglutinin staining (data not shown, Aulthouse and solursh, 1987), but it blocked cartilage nodule formation as determined by Alcian blue staining (Figure 4A) and accumulation of sulfated proteoglycans (Figure 4B). These results indicate that COX-2 overexpression inhibits progression from precartilage condensation to cartilage nodule, indicating inhibition of the chondrogenesis of mesenchymal cells.

Figure 4.

Ectopic expression of COX-2 inhibits progression of precartilage condensation to cartilage nodules. Mesenchymal cells were transfected with either empty vector (CON) or cDNA for COX-2 wild type (COX-2-transfected). The cells were cultured for 4 days. Accumulation of sulfate glycosaminoglycans was determined by Alcian blue staining (A) and quantified by measuring absorbance at 600 nm (B). The data represent the results of a typical experiment or mean values and SD (n = 4).

Discussion

IL-1β is a major catabolic pro-inflammatory cytokine involved in cartilage destruction-associated processes, such as loss of the differentiated chondrocyte phenotype (dedifferentiation) and inflammation (Sandell and Aigner, 2001; Ghosh and Smith, 2002). We previously demonstrated that IL-1β induced COX-2 expression and dedifferentiation in primary culture chondrocytes (Kim, 2003).

We have also shown that ectopic expression of caveolin-1 contributes to the expression and activity of COX-2 (Kim et al., 2006) and that these caveolin-1-transfected cells causes dedifferentiation of articular chondrocytes (Yu et al., 2004).

Because cartilage, formed by differentiated chondrocytes, serves as a template for endochondral bone formation and because cartilage development is initiated by the differentiation of mesenchymal cells into chondrocytes (Ahrens et al., 1977; Sandell and Adler, 1999; Solursh, 1989), we therefore examined in this study whether ectopic expression of COX-2 mediates differentiation of chondrocytes. As expected, COX-2 overexpression caused chondrocytes dedifferentiation and inhibited chondrogenesis.

The metabolites of COXs activity have long been suspected to have a role in skeletal reparative processes. The administration of PGE2 has increased the rate of fracture healing in several animal models (Keller, 1996; Norrdin and Shith, 1998), indicating that the metabolites of COXs may be necessary for efficient bone healing. The effect of PGE2 on chondrocytes depends on the culture system, microenvironment, and physiological conditions (Schwartz et al., 1998; Amin et al., 2000). PGE2 exerts anabolic effects such as synthesis of proteoglycan and type II collagen and catabolic effects such as enhancing matrix degradation (Goldring et al., 1996; Abramson 1999). For example, PGE2 has been shown to promote chondrocyte differentiation in addition to its role in inflammation by increasing type II collagen expression (Goldring et al., 1996, 1999; Schwartz et al., 1998). However, the expression and activation of COX-2 and resultant PGE2 production are also believed to contribute to cartilage destruction by altering matrix degradation via matrix metalloproteinase (Abramson, 1999). In our culture system, we observed that the addition of exogenous PGE2 did not affect chondrocyte dedifferentiation (data not shown). Therefore, our results suggest that ectopic expression of COX-2 causes dedifferentiation of rabbit articular chondrocytes and chondrogenic differentiation of mesenchymal cells via PGE2-independent pathways.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the SRC/ERC program of MOST/KOSEF (R11-2002-098-05001-0).

Abbreviations

- COX

cyclooxygenase

References

- 1.Abramson SB. The role of COX-2 produced by cartilage in arthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 1999;7:380–381. doi: 10.1053/joca.1998.0217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahrens PB, Solursh M, Reiter RS. Stage-related capacity for limb chondrogenesis in cell culture. Dev Biol. 1977;60:69–82. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(77)90110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amin AR, Abramson SB. The role of nitric oxide in articular cartilage breakdown in osteoarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1998;10:263–268. doi: 10.1097/00002281-199805000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amin AR, Dave M, Attur M, Abramson SB. COX-2, NO, and cartilage damage and repair. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2000;2:447–453. doi: 10.1007/s11926-000-0019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aulthouse AL, Solursh M. The detection of a precartilage, blastoma-specific marker. Dev Biol. 1987;120:377–384. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(87)90240-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruder SP, Fink DJ, Caplan AI. Mesenchymal stem cells in bone development, bone repair, and skeletal regeneration therapy. J Cell Biochem. 1994;56:283–294. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240560809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cash DE, Bock CB, Schughart K, Linney E, Underhill TM. Retinoic acid receptor alpha function in vertebrate limb skeletogenesis: a moleculator of chondrogenesis. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:445–457. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.2.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi EM, Kwak SJ, Kim YM, Ha KS, Kim JI, Lee SW, Han JA. COX-2 inhibits anoikis by activation of the PI-3K/Akt pathway in human bladder cancer cells. EXP MOL MED. 2005;37:199–203. doi: 10.1038/emm.2005.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeLise AM, Fischer L, Tuan RS. Cellular interactions and signaling in cartilagae development. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2000;8:309–334. doi: 10.1053/joca.1999.0306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Demoor-Fossard M, Redini F, Boittin M, Pujol JP. Expression of decorin and biglycan by rabbit articular chondocytes. Effects of cytokines and phenotypic modulation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1398:179–191. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(98)00044-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dubois RN, Abramson SB, Crofford L, Gupta RA, Simon LS, van de Putte LV, Lipsky PE. Cyclooxygenase in biology and disease. FASEB J. 1998;12:1063–1073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duncan RL, Turner CH. Mechanotransduction and the functional response of bone to mechanical strain. Calcif Tissue Int. 1995;57:344–358. doi: 10.1007/BF00302070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forwood MR. Inducible cyclooxygenase (COX-2) mediates the induction of bone formation by mechanical loading in vivo. J Bone Miner Res. 1996;11:1688–1693. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650111112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghosh P, Smith M. Osteoarthritis, genetic and molecular mechanisms. Biogerontology. 2002;3:85–88. doi: 10.1023/a:1015219716583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldring MB, Birkhead JR, Suen LF, Yamin R, Mizuno S, Glowaacki J, Arbiser JL, Apperley JF. Interleukin-1 beta-modulated gene expression in immortalized human chondrocytes. J Clin invest. 1994;94:2307–2316. doi: 10.1172/JCI117595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldring MB, Suen LF, Yamin R, Lai WF. Regulation of Collagen Gene Expression by Prostaglandins and Interleukin-1beta in Cultured Chondrocytes and Fibroblasts. Am J Ther. 1996;3:9–16. doi: 10.1097/00045391-199601000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldring MB. Berenbaum F Human chondrocyte culture models for studying cyclooxygenase expression and prostaglandin regulation of collagen gene expression. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 1999;7:386–388. doi: 10.1053/joca.1998.0219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keller J. Effects of indomethacin and local prostaglandin E2 on fracture healing in rabbits. Dan Med Bull. 1996;43:317–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim SJ, Chun JS. Protein kinase C a and z regulate nitric oxide-induced NF-kB activation that mediates cyclooxygenase-2 expression and apoptosis but not dedifferentiation in articular chondrocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;303:206–211. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00305-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim SJ. Ectopic expression of caveolin-1 induces COX-2 expression in rabbit articular chondrocytes via MAP kinase pathway. Immune Network. 2006;6:123–127. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lefebvre V, Peeters-Joris C, Vaes G. Production of collagens, collagenase and collagenase inhibitor during the dedifferentiation of articular chondrocytes by serial subcultures. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990;1051:266–275. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(90)90132-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lefebvre V, Huang W, Harley VR, Goodfellow PN, de Crombrugghe B. SOX-9 is a potent activator of the chondrocyte-specific enhancer of the pro alpha 1(II) collagen gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2336–2346. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.4.2336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.NamKoong S, Lee SJ, Kim CK, Kim YM, Chung HT, Lee HS, Han JA, Ha KS, Kwon YG, Kim YM. Prostaglandin E2 stimulates angiogenesis by activating the nitric oxide/cGMP pathway in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Exp Mol Med. 2005;36:588–600. doi: 10.1038/emm.2005.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Norrdin RW, Shith MS. Systemic effects of prostaglandin E2 on vertebral trabecular remodeling in beagles used in a healing study. Calcif Tissue Int. 1998;42:363–368. doi: 10.1007/BF02556354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okada Y, Lorenzo JA, Freeman AM, Tomita M, Morham SG, Raisz LG, Pilbeam CC. Prostaglandin G/H synthase-2 is required for maxmal formation of osteoclast-like cells in culture. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:823–832. doi: 10.1172/JCI8195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oh CD, Chang SH, Yoon YM, Lee SJ, Lee YS, Kang SS, Chun JS. Opposing role of mitogen-activated protein kinase subtypes, Erk-1/2 and p38, in the regulation of chondrogenesis of mesenchymes. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:5613–5619. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.8.5613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ryu JH, Kim SJ, Kim SH, Oh CD, Hwang SG, Chun CH, Oh SH, Seong JK, Huh TL, Chun JS. Regulation of the chondrocyte phenotype by beta-catenin. Development. 2002;128:5541–5550. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.23.5541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sandell LJ, Adler P. Developmental patterns of cartilage. Front Biosci. 1999;4:D731–D742. doi: 10.2741/sandell. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sandell LJ, Aigner T. Articular cartilage and changes in arthritis. An introduction: cell biology of osteoarthritis. arthritis res. 2001;3:107–113. doi: 10.1186/ar148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwartz Z, Gilley RM, Sylvia VL, Dean DD, Boyan BD. The effect of prostaglandin E2 on costochondral chondrocytedifferentiation is mediated by cyclic adenosine 3',5'-monophosphate and protein kinase C. Endocrinology. 1998;139:1825–1834. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.4.5919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith W, Garavitito R, DeWitt D. Prostaglandin endoperoxide H synthases (cyclooxygenase)-1 and -2. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:33157–33160. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.52.33157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith WL, DeWitt DL, Garavito RM. Cyclooxygenases: structural, cellular, and molecular biology. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:145–182. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Solursh M. Differentiation of cartilage and bone. Curr opin Cell Biol. 1989;1:989–994. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(89)90070-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suponitzky I, Weinreb M. Differential effects of systemic prostaglandin E2 on bone mass in rat long bones and calvariae. J Endocrinol. 1998;156:51–57. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1560051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weinreb M, Suponitzky I, Keila S. Systemic administration of an anabolic dose of PGE2 in young rats increases the osteogenic capacity of bone marrow. Bone. 1997;20:521–526. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(97)00033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weston AD, Rosen V, Chandraratna RA, Underhill TM. Regulation of skeletal progenitor differentiation by the BMP and retinoid signaling pathways. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:679–690. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.4.679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu KK. Inducible cyclooxygenase and nitric oxide synthase. Adv Pharmacol. 1995;33:179–207. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(08)60669-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoon YM, Oh CD, Kim DY, Lee YS, Park JW, Huh TL, Kang SS, Chun JS. Epidermal growth negatively regulates chondrogenesis of mesenchymal cells by modulating the protein kinase C a, Erk-1, and p38 MAP kinase signaling pathways. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:12353–12359. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.16.12353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yoon YM, Kim SJ, Oh CD, Ju JW, Song WK, Yoo YJ, Huh TL, Chun JS. Maintenance of differentiated phenotype of articular chondrocytes by protein kinase C and extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:8412–8420. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110608200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu SM, Kim SJ. Regulation of chondrocyte differentiation and cyclooxygenase-2 expression by caveolin-1. J Nat Sci. 2004;11:27–36. [Google Scholar]