Abstract

Mutations in one of the 13 Fanconi anemia (FA) genes cause a progressive bone marrow failure disorder associated with developmental abnormalities and a predisposition to cancer. Although FA has been defined as a DNA repair disease based on the hypersensitivity of patient cells to DNA cross-linking agents, FA patients develop various developmental defects such as skeletal abnormalities, microphthalmia, and endocrine abnormalities that may be linked to transcriptional defects. Recently, we reported that the FA core complex interacts with the transcriptional repressor Hairy Enhancer of Split 1 (HES1) suggesting that the core complex plays a role in transcription. Here we show that the FA core complex contributes to transcriptional regulation of HES1-responsive genes, including HES1 and the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21cip1/waf1. Chromatin immunoprecipitation studies show that the FA core complex interacts with the HES1 promoter but not the p21cip1/waf1 promoter. Furthermore, we show that the FA core complex interferes with HES1 binding to the co-repressor transducin-like-Enhancer of Split, suggesting that the core complex affects transcription both directly and indirectly. Taken together these data suggest a novel function of the FA core complex in transcriptional regulation.

Fanconi anemia (FA)2 is a rare genetic disease with pleiotropic clinical manifestations. FA is characterized mainly by a progressive bone marrow failure, congenital defects, chromosomal instability, and cancer susceptibility. FA is defined by 13 genes (FANC-A to -N) (1–19), and the products of eight genes bind together in a nuclear “core complex” that possesses E3 ubiquitin ligase activity. This activity is required for mono-ubiquitination of FANCD2 and FANCI, known as the ID complex, in response to DNA damage or replication (11, 16, 20–25). Cells derived from FA individuals are hypersensitive to DNA cross-linking agents and exhibit chromosomal instability. For this reason, FA has been defined as a DNA repair disease. Although it is clear that FA proteins are involved in a DNA cross-link response network, the precise role of each protein remains unclear.

FA has a number of clinical manifestations that cannot be explained solely based on defects in cross-link repair. For example, developmental defects such as skeletal abnormalities commonly occur; the most frequent are hypoplasia of the thumbs or supernumerary thumbs (70% of patients), and microphtalmia or short stature (more than 60% of patients) (26). In addition, more than 70% of FA patients show endocrine abnormalities, including deficiencies in growth hormone and thyroid hormone, as well as diabetes (27, 28). Furthermore, the progressive bone marrow failure that is the primary characteristic of FA, and that results from defective self-renewal ability of hematopoietic stem cells (29, 30), has yet to be explained as a result of a defective cross-link repair. Thus, the various phenotypic features of the disease may stem from functional impairments other than DNA repair defects. Indeed, this is the case for the DNA repair syndrome trichothiodystrophy where dysfunctional basal transcription has been shown to underlie part of the trichothiodystrophy phenotype (31, 32).

Recently, we reported that several components of the FA core complex directly interact with the Hairy Enhancer of Split 1 (HES1) protein (33). HES1 is a member of a highly conserved family of Hairy-related basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH)-type transcriptional repressors. HES1 plays an essential role in the development of many organs by promoting the maintenance of stem/progenitor cells, by controlling the reversibility of cellular quiescence, and by regulating both cell fate decisions and the timing of several developmental events (34, 35). HES1 has also been associated with tetraploidy and chromosomal instability (36), both of which are involved in the early steps of tumorigenesis (37).

HES1 negatively regulates expression of downstream target genes and antagonizes the effects of bHLH activators (34, 38). Like other HES family members, HES1 is composed of three functional domains: a bHLH domain, an Orange domain, and a WRPW motif at the C terminus (38). The bHLH domain is required for both DNA binding and dimerization with other bHLH factors, whereas both the Orange domain and WRPW motif are involved in protein-protein interactions. The Orange domain seems to be involved in the selection of bHLH partners, and it is required for repression of its own gene (39). The WRPW motif mediates repression through recruitment of co-repressors encoded by Transducin-like Enhancer of split (TLE) genes (40, 41). We previously reported that both Orange and WRPW motifs are involved in HES1 interactions with FA core complex proteins (33).

Because HES1 is a transcriptional repressor, the direct interaction between HES1 and FA core complex members prompted us to examine whether the FA complex modulates HES1 transcriptional repression. Here, we present data showing that the FA core complex co-regulates HES1 transcriptional activity via activation and repression of HES1-responsive genes, including HES1 and the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21cip1/waf1. In addition, the interaction between HES1 and the FA core complex antagonizes HES1-mediated transcriptional repression by interfering with assembly of the HES1·TLE co-repressor.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Lines and Culture Conditions—HEK293T, COS-1, PD430 (FA-A), PS1–/–, and Hes1–/– fibroblast cell lines were grown at 37 °C, 5% CO2 in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. Cells were maintained in log phase prior to experiments. FA group A (PD430; gift from Dr. Markus Grompe, Oregon Health & Science University) and Hes1–/– (gift from Dr. Ryoichiro Kageyama, Kyoto University) fibroblasts were transformed with a plasmid encoding the SV40 large T antigen. Transformed cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Transfections were performed using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) or the calcium phosphate method.

Plasmids—FANCE, FANCF, and FANCG genes obtained from pREP4 expression plasmids in which they had originally been cloned (3, 5, 7) were subcloned by PCR into the mammalian expression vector pCDNA3 to generate fusions with Myc. The plasmid pFAC3, which expresses FANCC (4), and pREP4FAA, which expresses FANCA (6), were gifts from Dr. Manuel Buchwald (Hospital for Sick Children). The pIRESneo-FANCL plasmid, which expresses FLAG-tagged FANCL was a gift from Dr. Hans Joenje (Vrije Universiteit Medical Center). HES1 was subcloned into pCMVzeo in fusion with HA. The pCMV2-FLAG-HES1ΔWRPW plasmid was a gift from Dr. Stefano Stifani (McGill University). The Notch1 intracellular domain (NICD), the BACE1 and Lamin plasmid constructs have been described previously (42, 43). All constructs were verified by DNA sequencing.

Antibodies—Antibodies used were: goat anti-FANCA (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies), polyclonal anti-FANCC (44), rabbit polyclonal anti-FANCF (gift from Dr. Maureen Hoatlin, Oregon Health & Science University), rabbit polyclonal anti-FANCG and anti-FANCL (Fanconi Anemia Research Fund Inc.), rabbit polyclonal anti-HES1 (clone Ab5702, Chemicon, and clone H-140, Santa Cruz Biotechnologies), monoclonal anti-Notch1 (bTAN20, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), rabbit polyclonal anti-RBP-Jk (H50, Santa Cruz Biotechnologies), monoclonal anti-HA (12CA5, Roche Diagnostics), monoclonal anti-cMyc (9E10 Santa Cruz Biotechnologies), and anti-TLE antibodies (anti-TLE1 N-18, Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, and anti-TLE4, gift from Dr. Stefano Stifani, McGill University).

Immunoprecipitation and Western Blotting—Cells were grown for 40 h following transfection and harvested in lysis buffer (50 mm Tris, pH 7.6, 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, 0.2% Nonidet P-40, 0.5 or 1% Triton X-100, and Complete proteinase inhibitor (Roche Diagnostics)). Whole cell lysates were subjected to either immunoblot analysis or immunoprecipitation. For immunoprecipitation, cell lysates were incubated with 2 μg of antibodies as indicated in the figures. Immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE on 10% polyacrylamide gels and subjected to Western blotting and probing with specific antibodies as indicated in the figures. Negative immunoprecipitation controls were performed using either mouse or rabbit serum.

Luciferase Assays—In all assays, 1.25 × 105 COS-1 or FA-A fibroblast cells plated in 6-well plates were transfected with 0.38 μg of a plasmid containing the luciferase reporter gene driven by either the HES1 promoter (pHES1-Luc, gift from Dr. Ryoichiro Kageyama, Kyoto University), or 0.75 μg of p21cip1/waf1 promoter constructs (pGL3-p21cip1/waf1–2326/+16 (p21pro-Luc) or pGL3-p21cip1/waf1–60/+16 (p21proΔE8-E4-Luc), gifts from Dr. Claude Labrie, Laval University, and p21PE1–2 and p21PE1–3 (p21proΔE1–2-Luc or p21proΔE1–3-Luc) gifts from Dr. Xiao-Hong Sun, Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation). In addition, cells were transfected with 0.125 μg of pCMVLacZ (gift from Dr. Yves Labele, Laval University) as an internal control plasmid, as well as various other plasmids indicated in the figures. The total amount of plasmids DNA was equalized between transfections using empty vectors. Cell extracts were prepared 48 h following transfections and assayed for luciferase activity using the Luciferase assay system (Promega, Madison, WI). Transfection efficiencies were normalized with the internal control plasmid (pCMVLacZ) using the β-galactosidase luminescence kit II (Clontech). Differences between means were evaluated using Student's paired t test.

Quantitative PCRs—All animal procedures were performed according to protocols approved by the Animal Care Committee of Laval University, Québec, Canada. Bone marrow cells obtained from 4- to 6-month-old FancA–/–, FancC–/–, and wild-type mice (C57BL/6J) were collected from femurs and tibias. Bone marrow cells were depleted of lineage and Thy1.2-positive cells using the StemSep negative cell selection procedure according to the manufacturer's instructions (StemCell Technologies Inc.). Total RNA was isolated from freshly purified Lin–Thy1.2– cells using the RNeasy Mini Kit RNA purification system according to the manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen). Reverse transcription was carried out with random hexamer primers (Ambion) using the SuperScript™II protocol as described by the manufacturer (Invitrogen). Quantitative PCR was performed with 100 nm each of the forward and reverse Hes1 or Gapdh primers using the ABI Prism 7000 Sequence Detection System and SYBRGREEN DNA binding dye (Invitrogen). The specific amplification was assessed based on the dissociation curve profile, and product sizes were verified by agarose 2% gel fractionation. The Hes1 gene expression profile was normalized against that of Gapdh.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitations—Constructs were transfected into HEK293T cells using the calcium phosphate method. Transfected cells were grown for 40 h, treated with 1% formaldehyde for 20 min, and washed twice in cold phosphate-buffered saline containing 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and Complete proteinase inhibitors (Roche Diagnostics). Cells were lysed in SDS lysis buffer (1% SDS, 10 mm EDTA, 50 mm Tris, pH 8.1, Complete proteinase inhibitors, and 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) and subjected to immunoprecipitation with 2 μg of antibodies as indicated in each figure using the Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Assay Kit as described by the manufacturer (Upstate). Immunoprecipitated DNA sequences were purified using the phenol chloroform: isoamyl alcohol DNA precipitation method. Purified and input DNA were subjected to PCR using primers specific for the human HES1 promoter (forward primer: 5′-CAAGACCAAAGCGGAAAGAA-3′; reverse primer: 5′-GGATCCTGTGTGATCCCTAGGC-3′) and the p21cip1/waf1 promoter control region (forward primer: 5′-GGTGCTTCTGGGAGAGGTGAC-3′, and reverse primer: 3′-TGACCCACTCTGGCAGGCAAG-5′). PCR products were loaded on 1.5% agarose gels containing ethidium bromide. Band intensity was analyzed using the Quantity One analysis software (Bio-Rad). HES1 and p21cip1/waf1 promoter sequence amplification profiles were normalized to the corresponding negative control (mock ChIP using mouse serum). PCR controls were performed using water. Fold binding of proteins to the promoter relative to the control is presented as the mean ± S.D. Statistical analysis of the difference between means was done using the Student's paired t test.

RESULTS

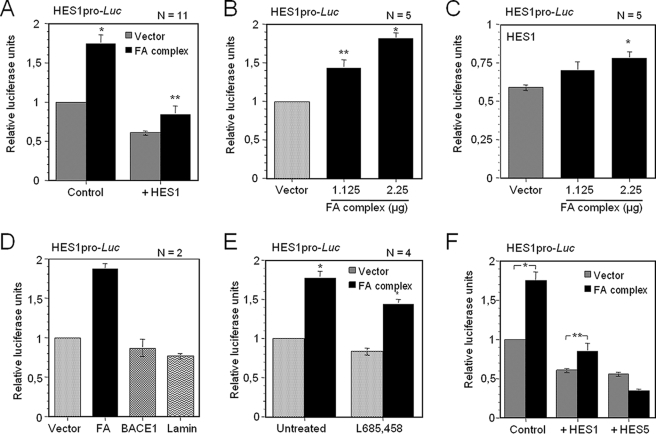

The FA Core Complex Acts as a Co-regulator of HES1 Transcription—HES1 has been shown to bind its own promoter via N-box sequences and to repress its own gene expression (39, 45). Using the HES1 promoter region to drive the luciferase gene (HES1pro-Luc), we tested the effect of the FA core complex on HES1-mediated transcriptional repression. We found that co-expression of FA core complex members significantly impaired HES1-mediated repression activity of its own gene (1.40-fold derepression, Fig. 1A, right panel). Surprisingly, the FA core complex significantly induced HES1 expression (1.75-fold induction, Fig. 1A, left panel). Both, the stimulatory effect of the FA core complex on HES1 transcription, and the inhibitory effect of the core complex on HES1-mediated repression of its own promoter occurred in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1, B and C, respectively). This FA core complex-mediated activity (activation and derepression of the HES1 promoter) was not the result of transfection or plasmid expression, because transfection of plasmids encoding the BACE1 or Lamin genes produced levels of luciferase expression similar to that of controls (Fig. 1D). In addition, the induction of the HES1 promoter was not the result of endogenous Notch1 activity, because treating the cells with the γ-secretase inhibitor L685,458, which blocks cleavage and activation of Notch1 (46), caused the same increase in luciferase activity in both treated and untreated cells (Fig. 1E).

FIGURE 1.

The FA complex activates HES1 transcription. A, FA core complex-mediated activation of the HES1 promoter. COS-1 cells were transiently transfected with the pHES1pro-Luc reporter vector using 2.25 μg of either an empty vector or vectors encoding components of the FA core complex (FANCA, FANCC, FANCE, FANCF, FANCG, and FANCL) with or without an equimolar amount of an HES1 expression plasmid (0.34 μg). Luciferase activities were determined 48 h after transfection. B, dose-dependent HES1 activation by the FA core complex. COS-1 cells were transiently transfected with the pHES1pro-Luc reporter vector and various concentrations of FA complex members as indicated. C, dose-dependent FA complex-mediated derepression of HES1. COS-1 cells were transiently transfected with pHES1pro-Luc and various concentrations of FA complex members as indicated together with the HES1 coding vector (0.34 μg). D, FA complex-mediated transcriptional activation of HES1 is specific. COS-1 cells were transiently transfected with pHES1pro-Luc and either components of the FA core complex or an equimolar amount of plasmids carrying the BACE1 or Lamin genes. E, FA complex-mediated activation of HES1 is independent of endogenous Notch1. COS-1 cells transfected with pHES1pro-Luc and plasmids encoding components of the FA complex (or empty vector as control) were treated with the γ-secretase inhibitor L685,458 (10 μm, 5 h) or DMSO (untreated). F, effect of FA core complex on HES5-mediated repression. COS-1 cells were transiently transfected with pHES1pro-Luc and either HES1 (n = 11) or HES5 (n = 2) coding vectors with or without FA complex components. Numbers of experiments are indicated in each graph. Each experiment was done in duplicate or triplicate determination. *, p = 0.0001; **, p < 0.0005.

To determine whether the FA complex-mediated transcriptional regulation of HES1 is specific for HES1, we evaluated HES5-mediated transcriptional repression. Of the seven described members of the mammalian HES family described so far, HES1 and HES5 have been shown to be up-regulated by Notch1 signaling in neural cells and in bone marrow (47, 48). HES5 is a repressor protein that also binds to N and E boxes of specific promoter sites, including the HES1 promoter. Results show that the FA core complex had no inhibitory effect on HES5-mediated repression but seemed to increase HES5-mediated repression of the HES1 promoter (Fig. 1F).

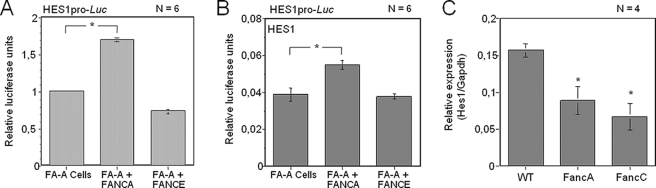

HES1 Transcriptional Regulation Is Impaired in FA Cells—To determine whether an intact FA complex or pathway is required for transcriptional regulation of the HES1 promoter, we evaluated HES1 activation in FA mutant cells (FA-A). We found that HES1 transcriptional activation was lower in FA-A cells, than in the corresponding FANCA-complemented cells (1.71-fold difference, Fig. 2A). In contrast, negative control FA-A cells expressing the FANCE gene showed similar levels of HES1 transcriptional activity as non-complemented cells. In addition, FA-A cells and FANCE-transfected FA-A cells showed higher HES1-mediated repression of the HES1 promoter than did FANCA-complemented FA-A cells (1.58-fold difference, Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 2.

Altered HES1 expression in FA mutant cells. A and B, reduced HES1 transcriptional activation in FA group A (FA-A) cells. FA-A cells were transiently transfected with pHES1pro-Luc and plasmids carrying either the correcting gene FANCA or, as a negative control, FANCE; in B, the HES1 expression plasmid was added to the transfection. Numbers of experiments are indicated in each graph. Each experiment was done in duplicate or triplicate determination. Absence of S.D. bars indicates that S.D. values were too low to appear visible. *, p = 0.0001. C, expression profile of Hes1 in freshly isolated primitive Lin–Thy1.2– hematopoietic cells using quantitative real-time PCR from four independent reactions. *, p < 0.05.

To determine whether the lack of a functional FA complex or pathway affects the level of HES1 expression in vivo, primitive hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells were isolated from FancA and FancC mutant mice. Quantitative real-time PCR showed lower HES1 expression in freshly isolated FancA–/– and FancC–/– primitive hematopoietic cells than in WT stem/progenitors (Fig. 2C). Together, these results imply that FA proteins, and possibly an intact FA complex/pathway, are required for proper transcriptional regulation of HES1.

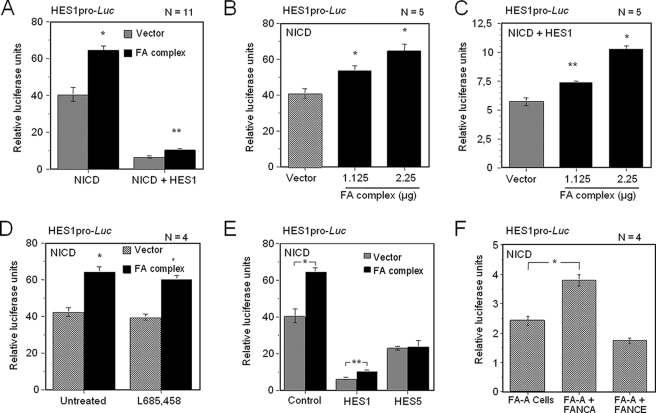

The FA Core Complex Enhances NICD-mediated Transcription of HES1—Because expression of the Notch1 intracellular domain (NICD), which is the active form of Notch1, has been shown to activate HES genes such as HES1, we tested the effect of the FA complex on NICD-mediated HES1 activation. Surprisingly, the FA complex enhanced NICD-mediated activation of the HES1 promoter, leading to a 1.59-fold increase in luciferase activity relative to NICD alone (Fig. 3A). This effect was mediated by the FA complex in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 3B), and it was not the result of endogenous Notch1 activity, because cells treated with L685,458 showed similar levels of luciferase activity (Fig. 3D). Co-expression of the FA complex with both NICD and HES1 significantly impaired HES1-mediated repression of its own gene in a concentration-dependant manner (1.59-fold difference, Fig. 3, A and C). These results suggest that the FA complex also modulates HES1 repression activity following Notch1 activation. This activity of the FA complex is specific to HES1, because no impairment of HES5-mediated repression was observed following Notch1 activation (Fig. 3E). Furthermore, FA-A cells and FA-A cells expressing FANCE showed lower NICD-mediated activation of the HES1 promoter than did FANCA-complemented cells (1.39-fold difference, Fig. 3F), suggesting that transcription of HES1 following Notch1 activation requires a functional FA complex or pathway.

FIGURE 3.

The FA complex enhances NICD-mediated activation of HES1 transcription. A, HES1 transcriptional activation following Notch1 activation. COS-1 cells were transfected with pHES1pro-Luc and NICD or both NICD and HES1 expression vectors with or without plasmids encoding FA complex component. All plasmids were transfected at equimolar ratios. B and C, FA complex-mediated HES1 activation is concentration-dependent. COS-1 cells were transiently transfected with pHES1pro-Luc and NICD and various concentrations of FA complex components as indicated; in C, the HES1-coding vector was added to the transfection. D, FA complex-mediated activation of HES1 is independent of endogenous Notch1. COS-1 cells transfected with pHES1pro-Luc and a plasmid encoding NICD with or without plasmids encoding components of the FA complex were treated with the γ-secretase inhibitor L685,458 (10 μm, 5 h) or DMSO (untreated). E, HES5-mediated repression following Notch1 activation. COS-1 cells were transiently transfected with pHES1pro-luc and a plasmid encoding NICD, vectors carrying either the HES1 (n = 11) or HES5 (n = 2) genes, and vectors encoding components of the FA complex. F, altered HES1 expression in FA mutant cells following Notch1 activation. FA-A cells were transiently transfected with pHES1pro-Luc and a plasmid encoding NICD as well as with a plasmid containing either the correcting FANCA or as a negative control, FANCE. Numbers of experiments are indicated in each graph. Each experiment was done in duplicate or triplicate determination. *, p = 0.0001; **, p < 0.001.

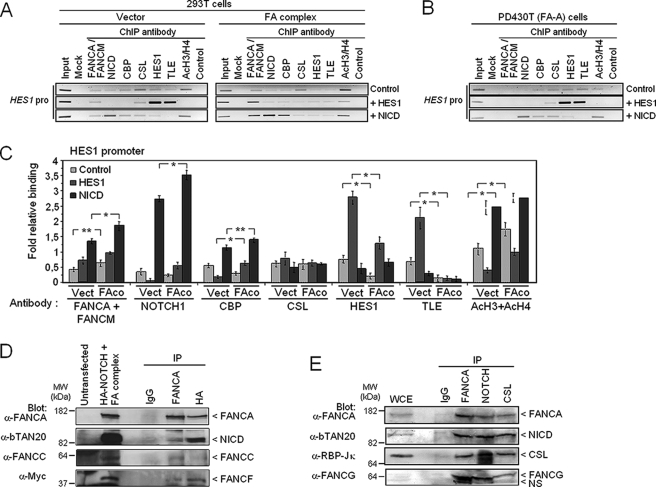

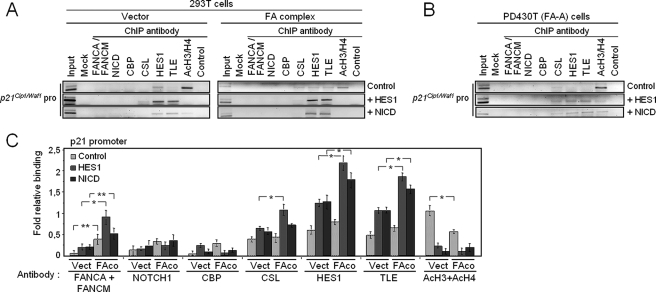

The FA Core Complex Is Located to the HES1 Promoter—To better understand the molecular mechanism of FA complex-dependent regulation of the HES1 promoter, ChIP experiments were carried out in 293T and FA-A cells. Binding of the FA core complex was assessed in conjunction with histone H3 and H4 acetylation, a chromatin modification associated with gene expression. We used a combination of anti-FANCA and anti-FANCM antibodies to immunoprecipitate the FA core complex. ChIP analysis of the HES1 promoter in 293T cells revealed the presence of the FA complex and members of the activator complex notably NICD, CBP, and CSL, together with HES1 (Fig. 4A, control lane in left panel; and C). Next, we tested FA complex recruitment to the HES1 promoter following transcriptional repression and activation of HES1 (Fig. 4, A and C). We found that repression of the HES1 gene by overexpression of HES1 correlated with increased TLE and HES1 binding to the HES1 promoter, whereas activation of HES1 through overexpression of NICD prevented TLE binding and decreased HES1 binding to the HES1 promoter. We also found that overexpression of NICD increased the recruitment of FA core complex and CBP to the HES1 promoter. However, no change in FA core complex binding to the HES1 promoter was observed following repression (+HES1), consistent with a role of the FA complex in HES1 transcriptional activation. The CSL DNA-binding protein was constitutively present at the HES1 promoter consistent with its role as a tether for both corepressor and coactivator complexes (49). In addition, overexpression of FA core complex components prevented HES1 and the corepressor TLE from binding to the HES1 promoter, but it enhanced NICD and CBP binding to the HES1 promoter (Fig. 4, A (right panel) and C). In addition, a greater amount of acetylated H3/H4 histones was found at the HES1 promoter in cells overexpressing FA core complex components than in untransfected cells (Fig. 4C). These results indicate increased HES1 promoter activation by the FA complex as shown in Fig. 1 and further suggest that the FA core complex regulates the transcription of HES1 by binding directly to the HES1 promoter or by preventing TLE recruitment to the HES1 promoter.

FIGURE 4.

The FA complex binds to the HES1 promoter and modulates NICD and HES1 recruitment. A, the FA core complex is located to the HES1 promoter. 293T cells were transfected with a vector carrying the HES1 or NICD gene or with an empty vector (left panel) in addition to vectors encoding components of the FA core complex (right panel). Cell lysates were subjected to ChIP with the indicated antibodies followed by PCR amplification of the HES1 promoter DNA sequence. Control immunoprecipitation was performed with mouse serum. B, absence of the FA core complex on the HES1 promoter in FA-deficient cells. FA-A (PD430T) cell lysates were subjected to ChIP using the indicated antibodies. PCR analysis was performed using primers specific for the HES1 promoter. C, relative binding of proteins to the HES1 promoter indicates the gel band intensity of the immunoprecipitated protein relative to that of the negative serum control. (n = 4) *, p = 0.0001; **, p = 0.005. D, FA core complex components co-immunoprecipitate with NICD. 293T cells were co-transfected with plasmids encoding components of the FA core complex and NICD and subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-FANCA antibodies, anti-HA (NICD) antibodies or pre-immune serum (IgG), followed by Western blotting with the indicated antibodies. E, endogenous FA proteins immunoprecipitate with NICD. Co-immunoprecipitation of endogenous proteins using anti-Notch1, anti-FANCA, anti-CSL, or serum (IgG) antibodies, followed by Western blotting with the indicated antibodies.

As expected, in cells with a disrupted FA complex, no FA core complex was detected on the HES1 promoter even following activation or repression of HES1 signaling (Fig. 4B and supplemental Fig. S1A). The binding of NICD, CBP, and CSL to the HES1 promoter, together with the amount of acetylated H3/H4 histones bound to the HES1 promoter was lower in FA-A cells than in wild-type cells. In addition, recruitment of HES1 and the co-repressor TLE to the HES1 promoter was greater in FA-A cells than in wild-type cells. These results are consistent with reduced HES1 expression in FA cells as shown in Fig. 2.

Furthermore, recruitment of NICD, CBP, and acetylated H3/H4 histones to the HES1 promoter was greater, and recruitment of HES1 and TLE lower, in wild-type cells overexpressing FA core complex components than in untransfected cells or FANCA-deficient cells (supplemental Fig. S1C). This increased binding of NICD to the HES1 promoter in cells overexpressing FA core complex components implies an association between NICD and the FA complex. Indeed, co-immunoprecipitation experiments using anti-FANCA or anti-HA (NICD) antibodies showed that FA proteins, including FANCA, FANCC, and FANCF, interact with NICD (Fig. 4D). To confirm that the interaction between FA proteins and NICD occurred endogenously, immunoprecipitation studies using endogenous protein extracts were performed using either anti-FANCA or anti-Notch1 antibodies. Western blot analysis of these immunoprecipitates revealed that endogenous FANCA, FANCG, and FANCL interact with NICD (Fig. 4E).

Because the DNA-binding transcription factor CSL (also known as CBF1 and RBPJk) is the primary effector of Notch1 and is required for both repression via HES1 (50) and activation via NICD, we tested for its presence in immunoprecipitates of endogenous proteins. Immunoprecipitation using either anti-FANCA or anti-Notch1 antibodies showed the presence of CSL (Fig. 4E). In addition, CSL immunoprecipitates contained the FA core complex components FANCA, FANCG, and FANCL as well as NICD. These results suggest that the FA core complex associates with the transcriptional activation machinery composed of NICD and CSL and thereby acts as a co-regulator of HES1 transcription.

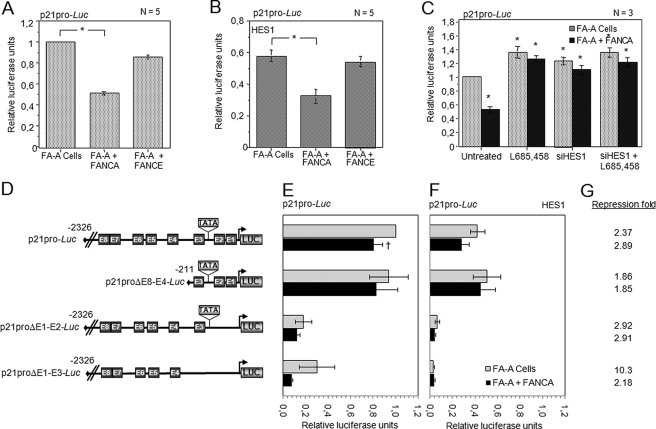

The FA Core Complex Regulates Expression of the HES1 Target Gene p21cip1/waf1—The p21cip1/waf1 promoter has been shown to contain multiple bHLH activator-binding sites (51) and to be a direct target for HES1 regulation (39). To determine whether the FA core complex regulation of HES1 affects other HES1 target genes, we used the p21cip1/waf1 promoter to drive the luciferase reporter gene in a transcriptional activation assay. First, we used the p21pro-Luc vector containing the full-length p21cip1/waf1 promoter, which contains the eight known E-box sites. This p21cip1/waf1 plasmid was transfected into FA-A mutant cells and in FANCA-corrected FA-A cells. Correction of FA-A cells with the FANCA gene reduced p21cip1/waf1 promoter activation to 1.93-fold the activation seen in uncorrected cells and negative control FA-A cells expressing the FANCE gene (Fig. 5A). Similar results were obtained in FA group C cells, with a 1.69-fold difference in p21cip1/waf1 transcriptional activation between FA-C- and FANCC-corrected cells (supplemental Fig. S2A). These results indicate that a functional FA pathway is required for p21cip1/waf1 gene repression, and they are consistent with the increased levels of p21cip1/waf1 reported in FA mutant cells relative to normal and FA-corrected cells (52). As expected, transfection of FA-deficient cells with HES1 reduced p21cip1/waf1 promoter activation below that in untransfected cells, whereas correction of these cells with the respective FA gene further reduced the p21cip1/waf1 promoter activity (Fig. 5B and supplemental Fig. S2B). In addition, levels of p21cip1/waf1 promoter activity were similar in both FA-corrected cells and in FA-deficient cells overexpressing HES1 (supplemental Fig. S2C), while FA-deficient cells treated either with the γ-secretase inhibitor L685,458 or Stealth Select RNA interference against HES1 showed levels of p21cip1/waf1 promoter activity similar to that in uncorrected cells (Fig. 5C). Furthermore, overexpression of FA core complex components in Hes1 knockout cells (Hes1–/–) or in presenilin knockout cells (PS1–/–) had no effect on p21cip1/waf1 promoter activity (supplemental Fig. S2D). These results imply that the FA core complex modulation of p21cip1/waf1 promoter activity requires HES1.

FIGURE 5.

Altered p21cip1/waf1 expression in FA mutant cells. A and B, increased p21cip1/waf1 transcriptional activation in FA-A mutant cells. FA-A cells were transiently transfected with the p21pro-Luc reporter vector and with vectors encoding either FANCA or as a negative control FANCE; in B the HES1 expression plasmid was added to the transfection. C, FA pathway-mediated repression of p21cip1/waf1 depends on HES1 activation and expression. FA-A- and FANCA-complemented cells transiently transfected with p21pro-Luc reporter vector were depleted of HES1 using either or both the γ-secretase inhibitor L685,458 (10 μm, 5 h) or Stealth Select RNA interference against HES1. Stealth RNA interference HES1 scrambled sequences were used as a negative control (untreated). Numbers of experiments are indicated in each graph. D, schematic representation of the p21cip1/waf1 promoter constructs. The full-length promoter sequence of the p21cip1/waf1 gene and deletion constructs were cloned upstream of the luciferase reporter gene as indicated. E-box sequences are shown as black boxes. E and F, transcriptional activity of p21cip1/waf1 promoter constructs in FA-A mutant cells and in FANCA-complemented cells. FA-A cells were transiently transfected with the p21pro-Luc, p21proΔE8-E4-Luc, p21proΔE1–2-Luc, or p21proΔE1–3-Luc reporter vectors and vectors carrying the FANCA gene or, as a negative control, an empty vector; in F, the HES1 expression plasmid was also transfected. Bars represent the mean ± S.E. of 4–8 separate experiments, each done in duplicate. G, relative HES1 repression activity of the p21cip1/waf1 promoter. The -fold relative repression indicates values obtained in cells without HES1 (in E) and in corresponding cells transfected with HES1 (in F). *, p = 0.0001; and †, p = 0.01.

Although the TATA box and all eight E boxes are necessary for efficient p21cip1/waf1 transcriptional activation, boxes E1–E3 have been shown to play a role in the p21cip1/waf1 transcriptional activation by the bHLH factor E47 or by Smad proteins (51, 53). To determine which regions of the p21cip1/waf1 promoter are important for FA complex-dependent HES1-mediated repression, we used different constructs of the p21cip1/waf1 promoter with deletions in the E boxes as illustrated in Fig. 5D. These p21cip1/waf1 promoter constructs were transfected into FA-A- and FANCA-corrected FA-A cells (Fig. 5E). Transcriptional activation measured with all p21cip1/waf1 promoter constructs, with or without HES1, was higher in FA-A cells than in FANCA-corrected cells (Fig. 5, E and F). A HES1-mediated repression was observed for all constructs used and ranged between 1.85- and 10.3-fold repression (Fig. 5G). The highest HES1-mediated repression observed in FA-A cells was obtained with the p21cip1/waf1 promoter construct lacking E1–E3 boxes indicating that the remaining E boxes were sufficient to exert a repression activity by HES1. The results suggest that the E-boxes are functionally redundant. In addition, these findings suggest that the FA core complex does not influence HES1 binding to the p21cip1/waf1 promoter, but instead they suggest that the FA complex acts through HES1 for transcriptional regulation of the p21cip1/waf1 promoter.

Indeed, ChIP analysis using anti-FANCA and anti-FANCM antibodies showed that the FA core complex is not recruited to the p21cip1/waf1 promoter following either activation (through NICD transfection) or repression (through HES1 transfection) of HES1 signaling (Fig. 6A). However, overexpressing components of the FA core complex significantly increased HES1 and TLE binding to the p21cip1/waf1 promoter following both activation and repression of the HES1 signal; this was associated with reduced binding of acetylated H3/H4 histones to the p21cip1/waf1 promoter (Fig. 6A (right panel), Fig. 6C, and supplemental Fig. S1D). ChIP analysis in FA-A cells showed increased amount of acetylated H3/H4 histones at the p21cip1/waf1 promoter (Fig. 6B and supplemental Fig. S1D); this effect was inhibited by transfection with HES1 or NICD. These results are consistent with increased p21cip1/waf1 promoter activity observed in FA mutant cells (Fig. 5 and supplemental Fig. S2), and they suggest an indirect role of the FA complex in p21cip1/waf1 regulation.

FIGURE 6.

The FA complex is not located to the p21cip1/waf1 promoter. A, 293T cells were transfected with a vector carrying either HES1, NICD, or an empty vector (left panel), as well as vectors encoding components of the FA core complex (right panel). Cell lysates were subjected to ChIP with the indicated antibodies followed by PCR amplification of the p21cip1/waf1 promoter sequence. Control immunoprecipitation was performed with mouse serum. B, p21cip1/waf1 promoter occupancy in FA-deficient cells. FA-A (PD430T) cell lysates were subjected to ChIP using the indicated antibodies. PCR analyses were performed with primers specific to the p21cip1/waf1 promoter. C, -fold relative binding of proteins to the p21cip1/waf1 promoter indicates the gel band intensity of the immunoprecipitated protein relative to that of the negative serum control. Bars represent the mean ± S.D. of 3–4 separate experiments each done in triplicates. *, p = 0.0001; **, p = 0.005.

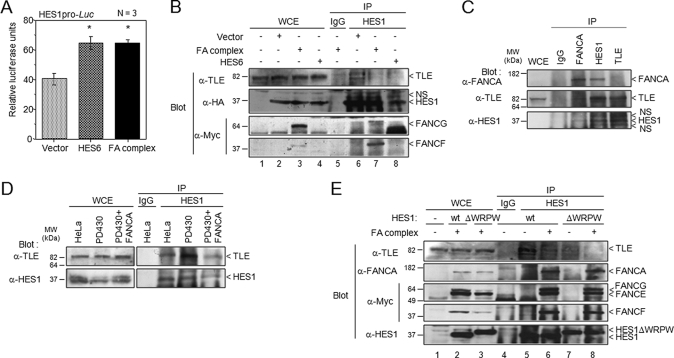

The FA Core Complex Interferes with the Formation of the HES1·TLE Co-repressor Complex—To elucidate the molecular mechanism by which the FA core complex modulates HES1-mediated transcriptional activity, we compared HES6 and the FA complex-mediated transcriptional activation of HES1. HES6 has been shown to antagonize the transcriptional repression activity of HES1 by preventing the formation of HES1·TLE co-repressor complexes (54, 55). Using the luciferase reporter system, we found that both the FA core complex and HES6 increased HES1 transcription to similar levels (Fig. 7A). Given that HES6 is known to compete with TLE for interacting with HES1 (54) and that components of the FA core complex interact directly with HES1 (33), we compared the effect of the FA core complex with that of HES6 on HES1·TLE complex formation. We found that endogenous TLE failed to co-immunoprecipitate with HES1 when co-transfected with FA core complex components or HES6 (Fig. 7B). Co-immunoprecipitation of endogenous proteins using anti-FANCA, anti-HES1, or anti-TLE antibodies showed that FANCA and TLE did not immunoprecipitate together with HES1 (Fig. 7C). Moreover, co-immunoprecipitations of endogenous proteins using anti-HES1 antibody showed that the interaction between HES1 and TLE is stronger in FA-A cells than in wild-type or FANCA-corrected cells (Fig. 7D). These results suggest that the FA core complex may prevent HES1·TLE complex formation by competing with TLE for HES1 binding.

FIGURE 7.

The FA complex competes with TLE for HES1 binding. A, FA complex-mediated HES1 transcriptional activation is similar to that of HES6. COS-1 cells were transfected with pHES1pro-Luc and either the HES6 expression vector or vectors encoding components of the FA core complex. Numbers of experiments are indicated in the graph. Each experiment was done in duplicate or triplicate determination. *, p = 0.0001. B, the FA complex interferes with HES1·TLE complex formation. 293T cells were transfected with equimolar amounts of the HES1 expression plasmid and plasmids encoding components of the FA core complex, HES6, or empty vectors. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation using anti-HES1 antibodies or control IgG followed by Western blotting with anti-Myc (FANCF and FANCG), anti-TLE and anti-HA (HES1) antibodies. C, the FA complex interferes with formation of endogenous HES1·TLE complex. Western blotting of endogenous proteins from 293T cells was carried out following immunoprecipitation with either anti-FANCA, anti-HES1, or anti-TLE antibodies or serum (IgG). D, HES1·TLE complex formation is enhanced in FA-deficient cells. FA-A cells (PD430) were transfected with a vector encoding FANCA or an empty vector. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation using anti-HES1 antibodies, followed by Western blotting with anti-TLE and anti-HES1 antibodies. E, the HES1 WRPW motif is not required for interaction with the FA core complex. 293T cells were transfected with plasmids encoding components of the FA core complex and a vector carrying either HES1 or HES1ΔWRPW. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-HES1 antibodies or control IgG, followed by Western blotting with anti-FANCA, anti-TLE, anti-Myc (FANCE, FANCF, and FANCG), and anti-HES1 antibodies. Control IgG immunoprecipitation was carried out with a mixture of protein extracts from cells transfected with vectors encoding components of the FA complex and a vector carrying HES1 or HES1ΔWRPW.

Given that the interaction of HES1 with TLE occurs through the WRPW motif on the C terminus of HES1 (56) and FA complex components (FANCF, FANCG, and FANCL) interact directly with the HES1 C-terminal region (33), we tested whether the FA complex antagonizes HES1 binding with TLE through the WRPW motif. Removal of the HES1 WRPW motif (HES1ΔWRPW) did not disrupt HES1·FA complex formation; however, as reported by McLarren et al. (56), it did prevent HES1 interaction with TLE (Fig. 7E). Moreover, deletion of the HES1 WRPW motif did not affect FA complex-mediated derepression of HES1 or following NICD-mediated activation (supplemental Fig. S3). These findings suggest that the HES1 WRPW motif is not essential for HES1·FA complex formation.

Our results clearly indicate that interactions between HES1 and the FA core complex interfere with formation of the HES1·TLE repressor complex, thus preventing or delaying repression of the HES1 gene.

DISCUSSION

The FA Core Complex Acts as a Transcriptional Co-activator Complex—In this study, we have continued to investigate the hypothesis that the FA complex/pathway is involved in cellular mechanisms other than DNA repair. Recently, we identified HES1 as a novel binding partner of the FA protein complex (33). Because HES1 is a transcriptional repressor, binding of HES1 with the FA core complex suggests that the FA complex/pathway is involved in transcription. Indeed, the present study finds that the FA core complex modulates transcription of the HES1 gene by impeding HES1-mediated self-repression and by enhancing NICD-mediated activation. The activity of NICD depends on its interaction with the transcription factor CSL; this interaction masks the repression domain of CSL thus converting it from a repressor to an activator while CSL interaction with HES1 negatively regulates NICD-dependent activation (57, 58). Because FA core complex proteins were found in NICD immunocomplexes together with the transcription factor CSL, it is likely that the FA core complex mediates HES1 transcriptional activation by acting through HES1. These data presented here show that the FA core complex modulates HES1 transcriptional repression activity, as well as HES1-mediated repression of HES1-responsive genes, including the HES1 gene itself. HES1 gene expression and HES1 promoter activity are both lower in FA-deficient cells than in normal or FA-corrected cells. Consequently, expression of HES1-responsive genes, such as p21cip1/waf1, should be affected. Indeed, increased levels of p21cip1/waf1 have been reported in FA mutant cells, including patient-derived lymphoblasts, mouse embryonic fibroblasts, and low density bone marrow cells (52). Moreover, the present study found p21cip1/waf1 transcriptional activation to be up-regulated in FA-deficient cells at the same time that HES1 gene expression levels were down-regulated. Correction of FA cells or overexpression of HES1 in FA cells lowered p21cip1/waf1 transcriptional activation to wild-type levels. Thus, the HES1-responsive gene p21cip1/waf1 is regulated by the FA complex/pathway via its binding partner HES1.

Binding of the FA Core Complex to the HES1 Promoter—FA core complex interactions with DNA have been suggested to occur in response to DNA damage through FANCM and the FA-associated protein FAAP24 (16, 59, 60). Given that the FA core complex interacts directly with the transcriptional repressor protein HES1 (33), and that it binds DNA (16, 59, 60) and modulates the transcriptional activation of the HES1 promoter (this study), we examined its role in transcriptional regulation of the HES1 promoter. In ChIP assays using antibodies against FANCM as the FA core complex DNA-binding protein and against FANCA as another core complex component, we found that the FA core complex localizes to the HES1 promoter during both repression (via HES1) and activation (via NICD). Lack of a functional complex/pathway prevented this association with the HES1 promoter, or the association of FANCA or FANCM as individual components with the HES1 promoter. Overexpression of FA core complex components reduced the binding of HES1·TLE co-repressor complex to the HES1 promoter in wild-type cells and increased the binding of co-activators (NICD and CBP). These data imply a direct role for the FA core complex in HES1 promoter activation. In contrast, this study failed to detect direct binding of the FA core complex to the p21cip1/waf1 promoter suggesting an indirect activity of the FA core complex on p21cip1/waf1.

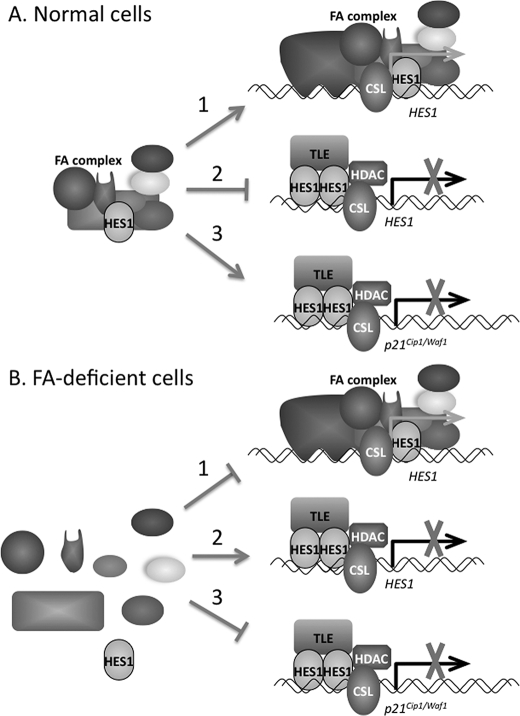

The FA Complex Interferes with the Formation of the HES1·TLE Co-repressor Complex—FA core complex proteins interaction with HES1 has been shown to occur via the HES1 Orange domain and WRPW motif (33). These domains play important roles in HES1-mediated transcriptional repression by recruiting other bHLH transcriptional regulators and co-repressors, such as the TLE co-repressor protein (39, 40). Interactions between HES1 and FA core complex interfere with formation of the HES1·TLE co-repressor complex. Our results show that the formation of the HES1·TLE complex was greater in FANCA-deficient cells than in normal or FANCA-complemented cells. In addition, HES1 seems to interact exclusively with either FA complex proteins or TLE, suggesting that the FA core complex may compete with TLE for HES1 binding. On the other hand, the TLE binding region of HES1, i.e. the C-terminal WRPW motif, is not essential for HES1 interaction with the FA core complex, even though this HES1 region is implicated in binding of FANCF to HES1 (33). Removal of the HES1 WRPW motif (HES1ΔWRPW) did not disrupt interactions between HES1 and the FA complex, but it did prevent TLE recruitment, suggesting that HES1·FA complex interactions depend mainly on the HES1 Orange domain. One possibility is that interactions between the FA complex and HES1 inhibit HES1 homodimerization and thereby prevent TLE recruitment, which in turn prevents the formation of a transcriptional co-repression complex (39). In this way, HES1 may become unavailable to interact with TLE, resulting in the prevention (or delay) of HES1 gene repression (Fig. 8A). Consequently, in the absence of a functional FA complex/pathway, HES1 may become available to TLE, leading to repression of the HES1 gene (Fig. 8B). Another possibility is that interactions between HES1 and the FA core complex influence HES1 affinity or specificity for other regulatory proteins or for gene promoters such as that of p21cip1/waf1. Because the FA core complex possesses an E3 ubiquitin-ligase activity, a possible mechanism of regulation by the FA core complex would be ubiquitination of HES1; this activity may influence the recruitment of HES1 co-regulators to certain promoters.

FIGURE 8.

Schematic representation of the FA complex-mediated regulation of HES1. A, in normal cells, transcriptional regulation of HES1 via the FA complex occurs through direct binding of the FA complex to the HES1 promoter (1), the prevention of HES1 interaction with TLE (2), or the influence of HES1 affinity for other gene promoters such as that of p21cip1/waf1 (3). B, in the absence of a functional FA complex, no FA core complex is located to the HES1 promoter (1), HES1 may become available to TLE leading to repression of HES1 (2), or decreased HES1 affinity to other gene promoters such as that of p21cip1/waf1 (3) may lead to an increase in p21cip1/waf1 expression.

In summary, our data reveal a novel function of the FA complex/pathway in transcriptional regulation; this function occurs through the binding of FA complex to HES1. We propose that the FA core complex regulates transcription through two mechanisms: one involving direct binding of the FA complex to the HES1 promoter, and another in which the FA complex prevents HES1 from interacting with its co-repressor TLE (Fig. 8). The involvement of the FA complex in transcriptional regulation of HES1-responsive genes points to a role of the FA complex in a signaling pathway implicated in stem cell maintenance and cell fate decisions within multiple tissues. Deregulation of this pathway though mutations in one of the FA core complex protein would explain developmental defects found in FA patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Maureen Hoatlin, Oregon Health & Science University, Dr. Markus Grompe, Oregon Health & Science University, Dr. Ryoichiro Kageyama, Kyoto University, Dr. Manuel Buchwald (Hospital for Sick Children), Dr. Hans Joenje (Vrije Universiteit Medical Center), Dr. Stefano Stifani (McGill University), Dr. Claude Labrie (Laval University), Dr. Yves Labelle (Laval University), Dr. Xiao-Hong Sun (Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation), and the Fanconi Anemia Research Fund Inc., for providing cells, plasmids, or antibodies.

This work was supported by grants from the Sickkids Foundation/Institute for Human Development, Child and Youth Health of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR, Grant XG 05-014R: Role of Fanconi anemia proteins in development), the Roche Foundation for Anemia Research and the Canadian Blood Services, and Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec Senior Investigator Awards (to G. L. and M. C.). Additional support was provided by training awards from La Fondation de la Recherche sur les Maladies Infantiles (to C. S. T.), the CIHR (to C. H.), and the FRSQ (to C. S. T.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: FA, Fanconi anemia; HES1, Hairy Enhancer of Split 1; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; NICD, Notch1 intracellular domain; CBP, CREB-binding protein; CSL, CBF1, RBPJk, Supressor of Hairless, Lag-1; TLE, transducin-like Enhancer of split 1; E3, ubiquitin-protein isopeptide ligase; bHLH, basic helix-loop-helix; CMV, cytomegalovirus.

References

- 1.Reid, S., Schindler, D., Hanenberg, H., Barker, K., Hanks, S., Kalb, R., Neveling, K., Kelly, P., Seal, S., Freund, M., Wurm, M., Batish, S. D., Lach, F. P., Yetgin, S., Neitzel, H., Ariffin, H., Tischkowitz, M., Mathew, C. G., Auerbach, A. D., and Rahman, N. (2007) Nat. Genet. 39 162–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xia, B., Dorsman, J. C., Ameziane, N., de Vries, Y., Rooimans, M. A., Sheng, Q., Pals, G., Errami, A., Gluckman, E., Llera, J., Wang, W., Livingston, D. M., Joenje, H., and de Winter, J. P. (2007) Nat. Genet. 39 159–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Winter, J. P., Rooimans, M. A., van Der Weel, L., van Berkel, C. G., Alon, N., Bosnoyan-Collins, L., de Groot, J., Zhi, Y., Waisfisz, Q., Pronk, J. C., Arwert, F., Mathew, C. G., Scheper, R. J., Hoatlin, M. E., Buchwald, M., and Joenje, H. (2000) Nat. Genet. 24 15–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strathdee, C. A., Gavish, H., Shannon, W. R., and Buchwald, M. (1992) Nature 356 763–767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Winter, J. P., Waisfisz, Q., Rooimans, M. A., van Berkel, C. G., Bosnoyan-Collins, L., Alon, N., Carreau, M., Bender, O., Demuth, I., Schindler, D., Pronk, J. C., Arwert, F., Hoehn, H., Digweed, M., Buchwald, M., and Joenje, H. (1998) Nat. Genet. 20 281–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lo Ten Foe, J. R., Rooimans, M. A., Bosnoyan-Collins, L., Alon, N., Wijker, M., Parker, L., Lightfoot, J., Carreau, M., Callen, D. F., Savoia, A., Cheng, N. C., van Berkel, C. G., Strunk, M. H., Gille, J. J., Pals, G., Kruyt, F. A., Pronk, J. C., Arwert, F., Buchwald, M., and Joenje, H. (1996) Nat. Genet. 14 320–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Winter, J. P., Leveille, F., van Berkel, C. G., Rooimans, M. A., van Der Weel, L., Steltenpool, J., Demuth, I., Morgan, N. V., Alon, N., Bosnoyan-Collins, L., Lightfoot, J., Leegwater, P. A., Waisfisz, Q., Komatsu, K., Arwert, F., Pronk, J. C., Mathew, C. G., Digweed, M., Buchwald, M., and Joenje, H. (2000) Am. J. Hum. Genet. 67 1306–1308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Fanconi Anaemia Breast Cancer Consortium (1996) Nat. Genet. 14 324–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Timmers, C., Taniguchi, T., Hejna, J., Reifsteck, C., Lucas, L., Bruun, D., Thayer, M., Cox, B., Olson, S., D'Andrea, A. D., Moses, R., and Grompe, M. (2001) Mol. Cell 7 241–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Howlett, N. G., Taniguchi, T., Olson, S., Cox, B., Waisfisz, Q., De Die-Smulders, C., Persky, N., Grompe, M., Joenje, H., Pals, G., Ikeda, H., Fox, E. A., and D'Andrea, A. D. (2002) Science 297 606–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meetei, A. R., de Winter, J. P., Medhurst, A. L., Wallisch, M., Waisfisz, Q., van de Vrugt, H. J., Oostra, A. B., Yan, Z., Ling, C., Bishop, C. E., Hoatlin, M. E., Joenje, H., and Wang, W. (2003) Nat. Genet. 35 165–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meetei, A. R., Levitus, M., Xue, Y., Medhurst, A. L., Zwaan, M., Ling, C., Rooimans, M. A., Bier, P., Hoatlin, M., Pals, G., de Winter, J. P., Wang, W., and Joenje, H. (2004) Nat. Genet. 36 1219–1224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levran, O., Attwooll, C., Henry, R. T., Milton, K. L., Neveling, K., Rio, P., Batish, S. D., Kalb, R., Velleuer, E., Barral, S., Ott, J., Petrini, J., Schindler, D., Hanenberg, H., and Auerbach, A. D. (2005) Nat. Genet. 37 931–933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levitus, M., Waisfisz, Q., Godthelp, B. C., Vries, Y., Hussain, S., Wiegant, W. W., Elghalbzouri-Maghrani, E., Steltenpool, J., Rooimans, M. A., Pals, G., Arwert, F., Mathew, C. G., Zdzienicka, M. Z., Hiom, K., De Winter, J. P., and Joenje, H. (2005) Nat. Genet. 37 934–935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bridge, W. L., Vandenberg, C. J., Franklin, R. J., and Hiom, K. (2005) Nat. Genet. 37 953–957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meetei, A. R., Medhurst, A. L., Ling, C., Xue, Y., Singh, T. R., Bier, P., Steltenpool, J., Stone, S., Dokal, I., Mathew, C. G., Hoatlin, M., Joenje, H., de Winter, J. P., and Wang, W. (2005) Nat. Genet. 37 958–963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dorsman, J. C., Levitus, M., Rockx, D., Rooimans, M. A., Oostra, A. B., Haitjema, A., Bakker, S. T., Steltenpool, J., Schuler, D., Mohan, S., Schindler, D., Arwert, F., Pals, G., Mathew, C. G., Waisfisz, Q., de Winter, J. P., and Joenje, H. (2007) Cell. Oncol. 29 211–218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sims, A. E., Spiteri, E., Sims, R. J., 3rd, Arita, A. G., Lach, F. P., Landers, T., Wurm, M., Freund, M., Neveling, K., Hanenberg, H., Auerbach, A. D., and Huang, T. T. (2007) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14 564–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smogorzewska, A., Matsuoka, S., Vinciguerra, P., McDonald, E. R., 3rd, Hurov, K. E., Luo, J., Ballif, B. A., Gygi, S. P., Hofmann, K., D'Andrea, A. D., and Elledge, S. J. (2007) Cell 129 289–301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Winter, J. P., van der Weel, L., de Groot, J., Stone, S., Waisfisz, Q., Arwert, F., Scheper, R. J., Kruyt, F. A., Hoatlin, M. E., and Joenje, H. (2000) Hum. Mol. Genet. 9 2665–2674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garcia-Higuera, I., Kuang, Y., Naf, D., Wasik, J., and D'Andrea, A. D. (1999) Mol. Cell. Biol. 19 4866–4873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Medhurst, A. L., Huber, P. A., Waisfisz, Q., de Winter, J. P., and Mathew, C. G. (2001) Hum. Mol. Genet. 10 423–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garcia-Higuera, I., Kuang, Y., Denham, J., and D'Andrea, A. D. (2000) Blood 96 3224–3230 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kruyt, F. A., Abou-Zahr, F., Mok, H., and Youssoufian, H. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274 34212–34218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Waisfisz, Q., de Winter, J. P., Kruyt, F. A., de Groot, J., van der Weel, L., Dijkmans, L. M., Zhi, Y., Arwert, F., Scheper, R. J., Youssoufian, H., Hoatlin, M. E., and Joenje, H. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96 10320–10325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dokal, I. (2000) Baillieres Best Pract. Res. Clin. Haematol. 13 407–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wajnrajch, M. P., Gertner, J. M., Huma, Z., Popovic, J., Lin, K., Verlander, P. C., Batish, S. D., Giampietro, P. F., Davis, J. G., New, M. I., and Auerbach, A. D. (2001) Pediatrics 107 744–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giri, N., Batista, D. L., Alter, B. P., and Stratakis, C. A. (2007) J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 92 2624–2631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carreau, M., Gan, O. I., Liu, L., Doedens, M., Dick, J. E., and Buchwald, M. (1999) Exp. Hematol. 27 1667–1674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haneline, L. S., Gobbett, T. A., Ramani, R., Carreau, M., Buchwald, M., Yoder, M. C., and Clapp, D. W. (1999) Blood 94 1–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keriel, A., Stary, A., Sarasin, A., Rochette-Egly, C., and Egly, J. M. (2002) Cell 109 125–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Compe, E., Malerba, M., Soler, L., Marescaux, J., Borrelli, E., and Egly, J. M. (2007) Nat. Neurosci. 10 1414–1422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tremblay, C. S., Huang, F. F., Habi, O., Huard, C. C., Godin, C., Levesque, G., and Carreau, M. (2008) Blood 112 2062–2070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kageyama, R., Ohtsuka, T., and Kobayashi, T. (2007) Development 134 1243–1251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sang, L., Coller, H. A., and Roberts, J. M. (2008) Science 321 1095–1100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baia, G. S., Stifani, S., Kimura, E. T., McDermott, M. W., Pieper, R. O., and Lal, A. (2008) Neoplasia (New York) 10 604–612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ganem, N. J., Storchova, Z., and Pellman, D. (2007) Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 17 157–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iso, T., Kedes, L., and Hamamori, Y. (2003) J. Cell. Physiol. 194 237–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Castella, P., Sawai, S., Nakao, K., Wagner, J. A., and Caudy, M. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 20 6170–6183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grbavec, D., and Stifani, S. (1996) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 223 701–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paroush, Z., Finley, R. L., Jr., Kidd, T., Wainwright, S. M., Ingham, P. W., Brent, R., and Ish-Horowicz, D. (1994) Cell 79 805–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hebert, S. S., Bourdages, V., Godin, C., Ferland, M., Carreau, M., and Levesque, G. (2003) Neurobiol. Dis. 13 238–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Godin, C., Auclair, A., Ferland, M., Hebert, S. S., Carreau, M., and Levesque, G. (2003) Neuroreport 14 1613–1616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brodeur, I., Goulet, I., Tremblay, C. S., Charbonneau, C., Delisle, M. C., Godin, C., Huard, C., Khandjian, E. W., Buchwald, M., Levesque, G., and Carreau, M. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 4713–4720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takebayashi, K., Sasai, Y., Sakai, Y., Watanabe, T., Nakanishi, S., and Kageyama, R. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269 5150–5156 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Martys-Zage, J. L., Kim, S. H., Berechid, B., Bingham, S. J., Chu, S., Sklar, J., Nye, J., and Sisodia, S. S. (2000) J. Mol. Neurosci. 15 189–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ohtsuka, T., Ishibashi, M., Gradwohl, G., Nakanishi, S., Guillemot, F., and Kageyama, R. (1999) EMBO J. 18 2196–2207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kawamata, S., Du, C., Li, K., and Lavau, C. (2002) Oncogene 21 3855–3863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ju, B. G., Solum, D., Song, E. J., Lee, K. J., Rose, D. W., Glass, C. K., and Rosenfeld, M. G. (2004) Cell 119 815–829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.King, I. N., Kathiriya, I. S., Murakami, M., Nakagawa, M., Gardner, K. A., Srivastava, D., and Nakagawa, O. (2006) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 345 446–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Prabhu, S., Ignatova, A., Park, S. T., and Sun, X. H. (1997) Mol. Cell. Biol. 17 5888–5896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fagerlie, S. R., Diaz, J., Christianson, T. A., McCartan, K., Keeble, W., Faulkner, G. R., and Bagby, G. C. (2001) Blood 97 3017–3024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pouliot, F., and Labrie, C. (2002) J. Endocrinol. 172 187–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gratton, M. O., Torban, E., Jasmin, S. B., Theriault, F. M., German, M. S., and Stifani, S. (2003) Mol. Cell. Biol. 23 6922–6935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jhas, S., Ciura, S., Belanger-Jasmin, S., Dong, Z., Llamosas, E., Theriault, F. M., Joachim, K., Tang, Y., Liu, L., Liu, J., and Stifani, S. (2006) J. Neurosci. 26 11061–11071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McLarren, K. W., Theriault, F. M., and Stifani, S. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 1578–1584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bray, S., and Furriols, M. (2001) Curr. Biol. 11 R217–R221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pursglove, S. E., and Mackay, J. P. (2005) Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 37 2472–2477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xue, Y., Li, Y., Guo, R., Ling, C., and Wang, W. (2008) Hum. Mol. Genet. 17 1641–1652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mosedale, G., Niedzwiedz, W., Alpi, A., Perrina, F., Pereira-Leal, J. B., Johnson, M., Langevin, F., Pace, P., and Patel, K. J. (2005) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12 763–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.