Abstract

In animal models, the dysregulated activity of calcium-activated proteases, calpains, contributes directly to cataract formation. However, the physiological role of calpains in the healthy lens is not well defined. In this study, we examined the expression pattern of calpains in the mouse lens. Real time PCR and Western blotting data indicated that calpain 1, 2, 3, and 7 were expressed in lens fiber cells. Using controlled lysis, depth-dependent expression profiles for each calpain were obtained. These indicated that, unlike calpain 1, 2, and 7, which were most abundant in cells near the lens surface, calpain 3 expression was strongest in the deep cortical region of the lens. We detected calpain activities in vitro and showed that calpains were active in vivo by microinjecting fluorogenic calpain substrates into cortical fiber cells. To identify endogenous calpain substrates, membrane/cytoskeleton preparations were treated with recombinant calpain, and cleaved products were identified by two-dimensional difference electrophoresis/mass spectrometry. Among the calpain substrates identified by this approach was αII-spectrin. An antibody that specifically recognized calpain-cleaved spectrin was used to demonstrate that spectrin is cleaved in vivo, late in fiber cell differentiation, at or about the time that lens organelles are degraded. The generation of the calpain-specific spectrin cleavage product was not observed in lens tissue from calpain 3-null mice, indicating that calpain 3 is uniquely activated during lens fiber differentiation. Our data suggest a role for calpains in the remodeling of the membrane cytoskeleton that occurs with fiber cell maturation.

Calpains comprise a family of cysteine proteases named for the calcium dependence of the founder members of the family, the ubiquitously expressed enzymes, calpain 1 (μ-calpain) and calpain 2 (m-calpain). The calpain family includes more than a dozen members with sequence relatedness to the catalytic subunits of calpain 1 and 2. Calpains have a modular domain architecture. By convention, the family is subdivided into classical and nonclassical calpains, according to the presence or absence, respectively, of a calcium-binding penta-EF-hand module in domain IV of the protein (1). Classical calpains include calpain 1, 2, 3, 8, 9, and 11. Nonclassical calpains include calpain 5, 6, 7, 10, 12, 13, and 14.

Transgenic and gene knock-out approaches in mice have demonstrated an essential role for calpains during embryonic development. Knock-out of the small regulatory subunit (Capn4) results in embryonic lethality (2, 3). Similarly, inactivation of the Capn2 gene blocks development between the morula and blastocyst stage (4). In humans, mutations in CAPN3 underlie limb-girdle muscular dystrophy-2A, and polymorphisms in CAPN10 may predispose to type 2 diabetes mellitus (5, 6).

Even under conditions of calcium overload, where calpains are presumably activated maximally, only a subset (<5%) of cellular proteins are hydrolyzed (7). Calpains typically cleave their substrates at a limited number of sites to generate large polypeptide fragments that, in many cases, retain bioactivity. Thus, under physiological conditions, calpains probably participate in the regulation of protein function rather than in non-specific protein degradation.

More than 100 proteins have been shown to serve as calpain substrates in vitro, including cytoskeletal proteins (8), signal transduction molecules (9), ion channels (10), and receptors (11). In vivo, calpains are believed to function in myoblast fusion (12), long term potentiation (13), and cellular mobility (14). Unregulated calpain activity, secondary to intracellular calcium overload, is associated with several pathological conditions, including Alzheimer disease (15), animal models of cataract (16), myocardial (17), and cerebral ischemia (18).

In addition to their domain structure, calpains are often classified according to their tissue expression patterns. Calpain 1, 2, and 10 are widely expressed in mammalian tissues, but other members of the calpain family show tissue-specific expression patterns. Calpain 8, for example, is a stomach-specific calpain (19), whereas expression of calpain 9 is restricted to tissues of the digestive tract (20). The expression of calpain 3 was originally thought to be limited to skeletal muscle (21), but splice variants of calpain 3 have since been detected in a range of tissues. At least 12 isoforms of calpain 3 have been described in rodents (22), of which several are expressed in the mammalian eye, including Lp82 (lens), Cn94 (cornea), and Rt88 (retina) (23).

Calpains have been studied intensively in the ocular lens because of their suspected involvement in lens opacification (cataract). Calpain-mediated proteolysis of lens crystallin proteins causes increased light scatter (24). Unregulated activation of calpains is observed in rodent cataract models (25), where calpain-mediated degradation of crystallin proteins (26) and cytoskeletal elements (27) is commonly observed. Calpain inhibitors are effective in delaying or preventing cataract in vitro (28, 29) and in vivo (30, 31).

It is likely, however, that calpains have important physiological roles in the lens beyond their involvement in tissue pathology. Terminal differentiation of lens fiber cells involves a series of profound morphological and biochemical transformations. For example, differentiating lens fiber cells undergo an enormous (>100-fold) increase in cell length, accompanied by extensive remodeling of the plasma membrane system (32). Early in the differentiation process, fusion pores are established between cells, as neighboring fibers are incorporated into the lens syncytium (33). A later stage of fiber cell differentiation involves the dissolution of all intracellular organelles, a process that is thought to eliminate light-scattering particles from the light path and contribute to the transparency of the tissue (34). Any or all of these phenomena might require the developmentally regulated activation of calpains. This is consistent with our previous observation that in calpain 3 knock-out mice the transition zone is altered, suggesting a change in the differentiation program (35).

In the current study, therefore, we examined the depth-dependent expression pattern and activity of calpains in the mouse lens. Fluorogenic substrates were microinjected into the intact lens to visualize calpain activity directly, and proteomic approaches were used to identify endogenous calpain substrates. The cleavage pattern of one of these, αII-spectrin, was examined in detail. Immunocytochemical and immunoblot analysis with wild type and calpain 3-null lenses indicated that αII-spectrin is a specific calpain 3 substrate in maturing lens fiber cells. Together, the data suggest that calpains are activated relatively late in fiber cell differentiation and may contribute to the remodeling of the membrane cytoskeleton that accompanies fiber cell maturation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals—Unless otherwise specified, 4–6-week-old mice were used. Wild type mice (C57/BL6) were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). The generation of caspase 3-null mice and calpain 3-null mice has been described previously (36, 37). The animals were killed by CO2 inhalation. The eyes were enucleated, and the lenses were removed using fine forceps, through an incision in the posterior of the eye globe. All of the procedures described herein were approved by the Washington University Animal Studies Committee and the Animal Care Committee of the University of Illinois at Chicago.

RNA Preparation—The lenses from 6-week-old wild type 129SvJae mice were dissected in RNase-free medium, transferred immediately into ice-cold extraction reagent (TRIzol; Invitrogen), and stored at -80 °C. Twenty to thirty lenses from each group were pooled, and total RNA was isolated according to the manufacturer's protocol. Isolated RNA was further purified using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen). RNA integrity was verified by visualization of the 28 and 18 S ribosomal RNA bands. The results represent the data from three independent pools.

Real Time PCR—Total lens RNA (2 μg) was used for generation of cDNA by reverse transcription using a kit according to the manufacturer's protocol (DYNAmo Sybr Green two-step qRT-PCR kit; New England Biolabs, MA). Using an ABI 7900HT Fast Real Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems Inc., CA), the cDNA was amplified, using the same kit (DYNAmo Sybr Green 2-step qRT-PCR kit; New England Biolabs, MA), with the products detected by SYBR Green I dye staining during the amplification. Real time amplifications were run in triplicate. The cycling conditions consisted of 1 cycle at 95 °C for 30 s for denaturing followed by 40 three-step cycles for amplification (each cycle consisted of 95 °C incubation for 10 s, 55 °C annealing temperature for 20 s, and product elongation and signal acquisition at 70 °C incubation for 30 s). Primer pairs used were: 5′-ACCACATTTTACGAGGGCAC-3′ and 5′-GGATCTTGAACTGGGGGTTT-3′ for calpain 1, 5′-CCCCAGTTCATTATTGGAGG-3′ and 5′-AAGCTCTGATCTGGAGGCAC-3′ for calpain 2, 5′-AGTGCCTCTTTGAAGACCGT-3′ and 5′-AGTGCCTCTTTGAAGACCGT-3′ for calpain 3 Lp82, 5′-TTCATCAGCTGCTTGGTCAG-3′ and 5′-AGCCACTCCTGGATGTTCAC-3′ for calpain 4, 5′-ATCTGGAAAGAGTGCAAGCC-3′ and 5′-GGCACGTTCTAGATCCAACTG-3′ for calpain 7, and 5′-GAGCAGTCAGCCTTCCAGAC-3′ and 5′-TCTGTGGTACTCATGCTGGG-3′ for calpastatin. All of the primers were derived using the qPrimerDepot data base. An equivalent amount of lens cDNA from the different mice was used, as normalized by their content of 18 S rRNA. At the end of the amplification, a melting curve analysis, ranging from 60 to 90 °C, was done and demonstrated the lack of formation of primer-dimers. Fold changes are reported relative to expression of Capn1.

Antibodies—The calpain antibodies used were: calpain 1 (ab39170; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), calpain 2 (ab39165; Abcam), calpain 7 (ab38937; Abcam), calpain 9 (SC-50502; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Santa Cruz, CA), calpain 10 (ab28226; Abcam), and calpain 3 isoform lp82/85 (38). The spectrin antibodies were: αII spectrin (MAB1622; Chemicon, Temecula, CA) and α-bdp1, which recognizes calpain-cleaved αII spectrin (39). The following organelle-specific antibodies were used: calnexin (anSPA-865; StressGen, Victoria, Canada), an integral protein of the endoplasmic reticulum, and succinate-ubiquinol-oxidoreductase (A11142; Invitrogen), a mitochondrial membrane protein.

Isolation of Proteins from Different Lens Strata—Concentric layers of lens fiber cells were removed progressively by controlled lysis, according to the method of Pierscionek and Augusteyn (40). Briefly, pools of 8–10 decapsulated wild type mouse lenses were progressively dissolved in 300 μl of buffer A (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 1% SDS) for calpain detection or buffer B (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 100 mm KCl, 5 mm EDTA, 4 mm dithiothreitol) for spectrin, calnexin, and succinate-ubiquinol-oxidoreductase detection, respectively. Both buffers contained protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science). For activity measurements, the decapsulated lens was divided into cortical and core fractions, the latter comprising cells lying within half the radius of the lens center. The samples were lysed using disposable plastic tissue homogenizers, and the protein content was determined by BCA assay (Bio-Rad) using immunoglobulin G as standard.

Western Blot—Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE NuPAGE 4–12% or NuPAGE 10% Bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The blots were incubated overnight with primary antibody at 4 °C. Primary antibodies were detected using an horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Pierce) and chemiluminescence.

In Vitro Calpain Activity Assay—Freshly dissected P25 lenses were separated into cortical and core fractions, homogenized in sample buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm EGTA, 1 mm dithiothreitol), and frozen until use. The samples (100 μg of total protein) were mixed with 150 μl of activity buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mm CaCl2, 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol) containing 200 μm of fluorogenic calpain substrate (catalog number 208748; Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA) and incubated at 30 °C. The calpain substrate was an internally quenched fluorogenic peptide derived from the calpain cleavage site of αII-spectrin. Fluorescence was measured using a fluorescence microplate reader (Spectra MAX Gemini EM; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). The measurements were taken at 1-min intervals over a period of 30 min. In some instances, 100 μm calpain inhibitor SJA6017 (catalog number 208745; Calbiochem) was included.

In Vivo Calpain Activity Assay—The lenses were immobilized in 1.5% low melting point agarose dissolved in minimum essential medium and positioned on the stage of an inverted fluorescence microscope (Axiovert 200; Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY). Injection pipettes were pulled from 1.2-mm outer diameter thin wall borosilicate glass (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL), using a horizontal pipette puller (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA). The pipette tips had an average diameter of 1–2 μm. The substrate solution mix was introduced into the tip of the injection pipette and overlaid with 0.6 m LiCl. The lens fiber cells were microinjected iontophoretically with a mixture of fluorogenic calpain substrate (125 μg/ml; catalog number 208748; Calbiochem) and Alexa Fluor 350 (150 μg/ml; catalog number A10439; Invitrogen) dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4).2 The tip of the injection pipette was inserted through the capsule near the lens equator and positioned in the midcortical region of the lens (100–150 μm beneath the lens surface). Current (1 μA) was injected for 10 s using a dual current generator (model 260; WPI, Inc.). The images of the injected region were captured using 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole and fluorescein isothiocyanate filter sets (corresponding to the 442- and 518-nm emission peaks of Alexa Fluor 350 and cleaved calpain substrate, respectively). Pairs of images were collected at the time of injection and at 1-min intervals thereafter. Changes in fluorescence intensity in the injected region were quantified using Axiovision image analysis software (Zeiss). Fluorescence was normalized to values at time 0. Some injections were made into lenses that were preincubated for 2 h in the irreversible cysteine protease inhibitor E64 (Sigma-Aldrich).

Membrane/Cytoskeleton Preparation—Decapsulated lenses were dissected in cold buffer B (described above). Cortical fibers were isolated and transferred to a Dounce homogenizer. The sample was disrupted using 12 strokes of the homogenizer, diluted 20-fold, and centrifuged at low speed (500 × g, 10 min at 4 °C) to eliminate intact cells and nuclei. Finally, the membrane cytoskeleton was pelleted by ultracentrifugation at 18,000 × g (Beckman TLA 100.1 rotor) for 45 min at 4 °C. This step was repeated twice, and the final pellet was dissolved in buffer A (described above).

Proteomic Analysis—A two-dimensional difference gel electrophoresis (DIGE) approach was used to identify endogenous calpain substrates in cortical lens fiber cells, as described previously (41). Briefly, a membrane/cytoskeleton-enriched fraction was prepared in activity buffer. Recombinant calpain 2 (10 units) (catalog number 208718; Calbiochem) was added to half of the preparation. After 30 min of incubation at 37 °C, the samples were labeled with either 1-(5-carboxypentyl)-1′-propylindocarbocyanine halide N-hydroxysuccinimidyl ester (Cy3) or 1-(5-carboxypentyl)-1′-methylindodicarbocyanine halide N-hydroxysuccinimidyl ester (Cy5) and recombined. The recombined sample was subjected to first dimension isoelectric focusing on immobilized pH gradient strips (pH 3.0–10.0) in an Ettan IPGphor system (GE Healthcare). Second dimension separation was performed on 10% isocratic SDS/PAGE gels (20 × 24 cm). The images were acquired using a Typhoon 9400 scanner (GE Healthcare). Relative quantification of gel features was achieved using Decyder DIA and BVA software (GE Healthcare), as described (see supplemental data). Selected gel features were excised robotically and analyzed using a matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight instrument (ABI4700). Two-dimensional gel preparation and mass spectrometry analysis were performed by the Proteomics Core Facilities at Washington University in St Louis.

Immunocytochemistry—Lenses were dissected from new-born mice (postnatal day 3 (P3). Fixed lenses were embedded in 4% agarose in PBS and sliced at 150 μm using a Vibratome tissue processor (Vibratome series 1000 plus; TPI Inc., St Louis, MO). Lens slices were permeabilized in 0.1% Triton X-100/PBS for 30 min and blocked in 3% bovine serum albumin in PBS overnight. The slices were incubated in primary antibody overnight at 4 °C, washed in PBS, and incubated for 2 h in secondary antibody at 37 °C. Propidium iodide (1 μg/ml) was included in one of the washes for nuclear staining. The slices were coverslipped and examined using a confocal microscope (LSM 510; Zeiss).

RESULTS

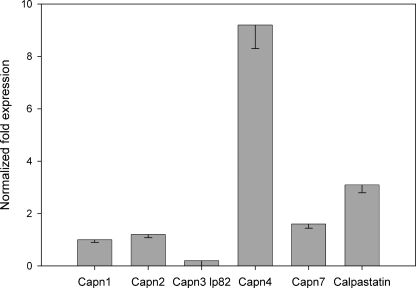

Calpain expression was evaluated in pooled lenses from 129SvJae wild type mice. Microarray analysis (data not shown) indicated the presence of calpain 1, calpain 2, calpain 3 isoform Lp82, and calpain 7 as well as calpastatin, a specific calpain inhibitor. Real time PCR analysis (qRT-PCR) confirmed microarray results and revealed that the transcript for the calpain small regulatory subunit (calpain 4) was the most abundant (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Relative expression of calpains in mouse lens, measured by qRT-PCR. Fold change (y axis) represents the relative expression of calpastatin, calpain 2, 4, and 7 and calpain3 lp82 in comparison to calpain1 normalized to 18 S reference gene expression.

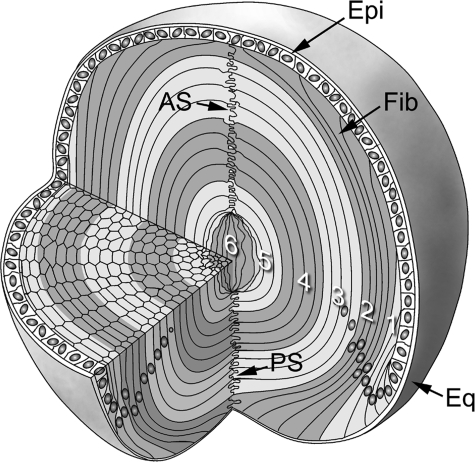

To examine the depth-dependent expression profile of calpain protein within the lens, a progressive tissue lysis protocol was adopted. Lenses have a fundamentally lamellar organization, because of the deposition of concentric shells of lens fiber cells (Fig. 2), and under appropriate conditions, material can be solubilized, layer-by-layer. The lenses were placed in lysis buffer and stirred gently. The lenses gradually dissolved over a period of approximately 1 h. By periodically decanting the lysate, it was possible to collect proteins emanating from the different strata of the tissue. In this manner, 7–11 fractions (depending on the size and age of the lenses) were obtained, corresponding to progressively deeper tissue layers, from the most superficial cells to the innermost cells of the lens core.

FIGURE 2.

Cellular organization of the mouse lens. The lens consists of two cell types: epithelial cells (Epi), which are present as a monolayer at the anterior surface, and concentric layers of fiber cells (Fib), which comprise the remainder of the tissue volume. Fiber cells are derived continuously by differentiation of epithelial cells at the lens equator (Eq). Newly differentiated fiber cells are added at the periphery. The tips of fibers extending from opposite hemispheres abut at the anterior (AS) and posterior (PS) sutures. The lens contains a complete cellular record and the age of a fiber cell can therefore be deduced from its radial location: those cells in the center of the tissue are the oldest, whereas those near the surface are the youngest. During their differentiation fiber cells lose their nuclei and other organelles. In this study, a progressive lysis technique was used to obtain material from the various lens strata (see “Experimental Procedures” for details). Fraction 1 (1) was derived from the outermost cell layers, whereas later fractions corresponded to progressively deeper strata. For clarity, the cells are not drawn to scale, and strata corresponding to the various fractions have been shaded.

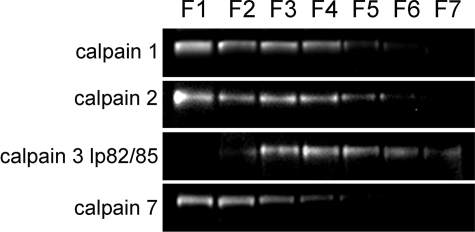

Depth-dependent expression profiles were obtained for calpains 1, 2, 3 (lp82/85 isoform), and 7 (Fig. 3). Neither calpain 9 nor calpain 10 (which, in other studies, has been shown to be expressed in the mouse lens (42)) were detected under these conditions (data not shown). The exposure time needed to visualize calpain 3 chemiluminescence was significantly shorter than for the other calpains, supporting the notion that calpain 3 is the most abundant calpain in the mouse lens, as reported previously (43). Calpain 1, 2, and 7 were abundant in the outer cell layers of the lens. For these enzymes, there was a steady decline in signal in fractions from the deeper, older, cell layers, and in the innermost fraction (F7), they were not detectable. In contrast, calpain 3 (lp82/85) was absent from F1, the outermost fraction. Calpain 3 signal first appeared in F2 and, although declining slightly with depth, was detected in the innermost (F7) fraction.

FIGURE 3.

Depth-dependent expression profiles of calpain proteases in the lens. Proteins were extracted from the various strata of the lens using a progressive lysis technique (see “Experimental Procedures” for details), which, in this example, generated seven fractions, from the outer cell layers (F1) to the lens core (F7). Calpain 1, 2, and 7 are readily detected in the outer cell layers, but their abundance decreases with depth, and these calpains are not detected in the innermost (F7) fiber cells. In contrast, calpain 3 is not detected in the outermost cells, first appearing in the cortical (F2) fraction. Calpain 3 signal is maximal in F3-F4 and persists in the innermost (F7) fraction.

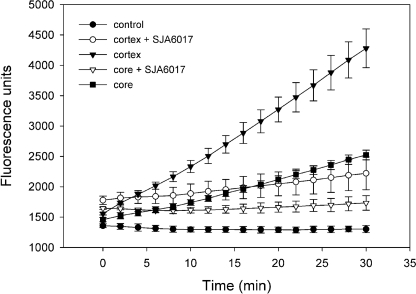

Calpain activity in core and cortical lens samples was quantified using a fluorogenic assay (Fig. 4). Cleavage of the fluorogenic calpain substrate was evident in samples prepared from the lens cortex. The addition of the calpain inhibitor, SJA6017, resulted in an 85% decrease in the rate of substrate hydrolysis, suggesting that most of the proteolytic activity in the cortical sample was attributable to calpain action. The samples isolated from the lens core had ∼2-fold less proteolytic activity, although the fractional decrease in activity in the presence of SJA6017 was greater in the core than in the cortical samples.

FIGURE 4.

Calpain activity in the mouse lens. Protease activity was measured in samples from the cortex or core of the lens using a fluorogenic assay. Calpain activity (the difference in rate of substrate hydrolysis in the presence or absence of the calpain inhibitor SJA6017) is 2.5-fold greater in the cortical samples than core samples.

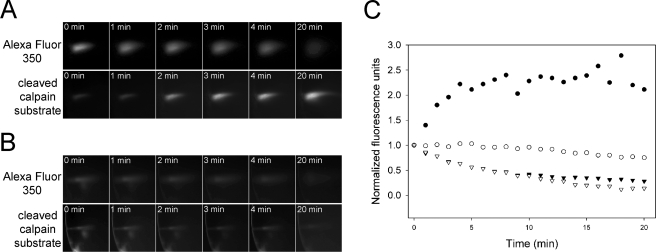

In vitro assays were performed under conditions (10 mm Ca2+) where all calpains were expected to be maximally active. To determine whether calpains were active in vivo, however, it was necessary to monitor proteolytic activity in the undisturbed tissue at physiological levels of calcium. Lenses are not innervated and lack a blood supply. As such, they can be dissected intact from the eye and survive well in organ culture. Furthermore, because of their inherent transparency, lenses lend themselves to analysis using optical techniques. To determine whether calpains are constitutively active in living lenses, we microinjected fluorogenic calpain substrate (molecular mass, 1595 Da) into individual cells in the lens cortex and monitored the hydrolysis of the substrate using microscopic techniques (Fig. 5). The cells were injected with a mixture containing Alexa Fluor 350 and fluorogenic calpain substrate. The Alexa Fluor was included to control for changes in fluorescence intensity resulting from diffusion or photobleaching of the dye. A typical result is shown in Fig. 5A. Shortly after injection, the Alexa Fluor 350 fluorescence was strong. However, over time, the signal became diffuse and less intense. Alexa Fluor 350 is a relatively small molecule (molecular mass, 349 Da) and is expected to pass through the gap junctions that interconnect lens fiber cells. The fall in signal intensity presumably reflected the diffusion of dye away from the injection point combined with the photobleaching effect of the illumination system. In contrast to Alexa Fluor 350, fluorescence corresponding to the hydrolyzed calpain substrate was initially weak but grew in intensity over time. This observation indicated that enzymes capable of cleaving the substrate were present and active in the cortical fiber cells. Significantly, pretreatment of lenses with the cysteine protease inhibitor E64, which is an effective calpain inhibitor in lens (44), completely blocked the hydrolysis of the calpain substrate (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 5.

Calpain activity in living cortical lens fiber cells. A mixture of Alexa Fluor 350 and fluorogenic calpain substrate was microinjected into individual cortical fiber cells in control lenses (A) or lenses pretreated with 100 μm cysteine protease inhibitor E64 (B). Changes in fluorescence intensity at the injection site were monitored over the following 20 min. In control or E64-treated lenses, Alexa Fluor 350 fluorescence becomes weaker and more diffuse with time, as a result of intercellular diffusion of the fluorescent probe and photobleaching by the illumination system. In contrast, in control lenses, the fluorescence corresponding to cleaved calpain substrate increases over time. This increase is blocked by pretreatment with E64. In C, the changes in fluorescence intensity (normalized to the initial signal) are quantified. Calpain substrate in control lenses (•), Alexa Fluor 350 in control lenses (▾) calpain substrate in E64-treated lenses (○), and Alexa Fluor 350 in E64-treated lenses (▿). The experiments are representative of five replicates.

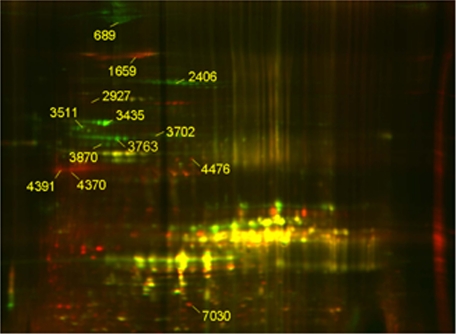

A proteomic analysis based on two-dimensional DIGE and tandem mass spectrometry was used to identify potential endogenous calpain substrates in lens fiber cells. A similar approach has been employed previously to identify substrates for the apoptosis-inducing protease granzyme B (41). The presence of extraordinarily high concentrations of crystallin proteins in the lens complicates the analysis of cytosolic proteins by two-dimensional gel methods. Consequently, we elected to examine the effect of calpain proteolysis on a membrane/cytoskeleton-enriched preparation. The membrane/cytoskeleton fraction was divided in two, and one sample was incubated with recombinant calpain 2. The protease-treated fraction was labeled with the red fluorescent dye, Cy5, and the untreated fraction was labeled with the green fluorescent dye, Cy3. Treated and untreated samples were recombined and separated on the same two-dimensional gel (Fig. 6). The gels were scanned sequentially to visualize the distribution of Cy3- and Cy5-labeled spots. More abundant spots in the untreated sample represented potential calpain substrates and appeared green. Spots that were more abundant in the protease-treated sample appeared red, indicating the presence of potential calpain cleavage products. Forty-eight red or green spots were excised from the gel and analyzed by tandem mass spectrometry. Twelve proteins passed the sequencing criteria (see supplemental data) and are shown in Table 1. All proteins were reidentified subsequently when the experiment was repeated with an independent biological sample (data not shown).

FIGURE 6.

Two-dimensional DIGE analysis of calpain-mediated cleavage of proteins from the lens membrane/cytoskeleton fraction. The membrane/cytoskeleton fraction was treated with (red) or without (green) recombinant calpain 2 (10 units) for 30 min at 37 °C. Dye-labeled samples were combined, and the protein mixture was separated subsequently in two dimensions. Proteins reduced in abundance following calpain treatment (i.e. calpain substrates) appear green. New spots appearing after calpain digestion (i.e. calpain cleavage products) appear red. Protein spots resistant to calpain digestion appear yellow. The numbered spots were excised and identified by mass spectrometry.

TABLE 1.

Calpain-induced changes identified by two-dimensional DIGE and mass spectrometry in cortical fiber cell membrane/cytoskeleton fraction

| Protein name | Protein identification code | Spot | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| αII spectrin | gi 20380003 | 689 | – |

| 1659 | + | ||

| βII spectrin | gi 117938332 | 2927 | + |

| Phakinin (CP49) | gi 50872159 | 3763 | – |

| 4370 | + | ||

| Filensin | gi 66792790 | 2406 | – |

| 4476 | + | ||

| Vimentin | gi 31982755 | 3435 | – |

| 4391 | + | ||

| Tubulin β5 | gi 7106439 | 3511 | – |

| Tubulin α1A | gi 6678465 | 3511 | – |

| β-Actin | gi 187951999 | 3870 | – |

| Lengsin | gi 23956410 | 3702 | – |

| NrCAM | gi 29466306 | 1659 | + |

| ATP synthase β | gi 2623222 | 3511 | – |

| αA-crystallin | gi 387134 | 7030 | + |

Several of the calpain substrates identified by mass spectrometry belonged to the family of intermediate filament proteins. The presence of vimentin (45), filensin (46), and CP49 (47) has been described previously in the lens. Lengsin, a member of the glutamine synthetase superfamily, is an abundant, lens-specific component of the lens membrane cytoskeleton (48). NrCAM, a neural cell adhesion molecule, and ATP synthetaseβ were also identified. Both αII and βII spectrin were detected. Spectrin, a preferred calpain substrate in many tissues, is a well known component of the lens membrane cytoskeleton (49). In ischemic neurons, calpain hydrolyzes αII spectrin (between Tyr1176 and Gly1177) to generate two unique stable breakdown products (50). Consequently, antibodies to calpain-cleaved αII spectrin have proved useful biomarkers for calpain-mediated ischemic brain injury (51).

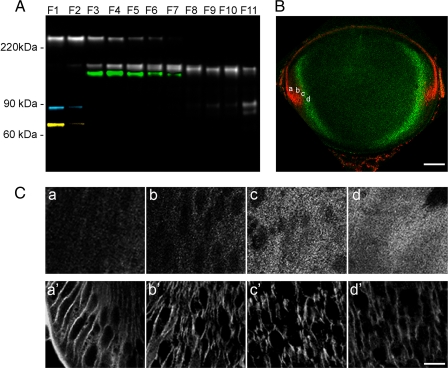

To determine whether spectrin serves as a calpain substrate during lens fiber cell differentiation, the lenses were fractionated using the progressive lysis method. A series of fractions was obtained from the lens surface to the lens center, transferred to nitrocellulose, and probed with antibody mAb 1622 (to an epitope in the C terminus of αII spectrin) or α-bdp1 (raised against a synthetic peptide, CQQEVY, corresponding to the novel C terminus produced by calpain cleavage). In the superficial layers (F1), only intact spectrin (∼280 kDa) was detected (Fig. 7A). However, beginning in fraction F2, the levels of intact spectrin declined steadily, such that the intact molecule was not detected in F8–F11. The decrease in the levels of intact spectrin was accompanied by an increase in the levels of spectrin breakdown products. Initially, a ∼150-kDa breakdown product was detected, and slightly later, a smaller product at ∼145 kDa was detected. In the later fractions (F9–11), only the 145-kDa product was detected. In the innermost fraction (F11), an additional breakdown product was observed at ∼90 kDa. To determine whether the depth-dependent cleavage of spectrin was due to calpain activation, the blots were stripped and reprobed with α-bdp1. A α-bdp1-positive fragment at ∼139 kDa was detected in F3–F8. The CQQEVY epitope is uniquely generated by calpain cleavage, suggesting the activation of calpains in the lens cortex.

FIGURE 7.

αII Spectrin is cleaved by calpain during fiber cell differentiation. A, proteins were extracted from various lens strata (F1–F11) by progressive lysis (see “Experimental Procedures” for details) and probed with mAb1622 (against an epitope near the C terminus of αII-spectrin; gray), α-bdp1 (against an epitope unique to calpain-cleaved spectrin; green), SPA-865 (against calnexin, an endoplasmic reticulum marker; blue) and A11142 (against succinate-ubiquinol-oxidoreductase, a mitochondrial marker; yellow). In the outermost cell layers (F1 and F2), spectrin is present as a single band at ∼280 kDa. With depth, however, the levels of intact spectrin are reduced, and the full-sized molecule is not detected beyond F6. Concomitant with the disappearance of intact (280 kDa) spectrin is the appearance, in F3, of a ∼150-kDa cleavage product, corresponding to the C-terminal portion of the parent molecule. A second, slightly smaller C-terminal fragment (∼145 kDa) appears at F5, and this fragment persists in the innermost cells. An additional C-terminal fragment is detected in the innermost (F11) fraction. A calpain-cleaved fragment (green) appears in fraction F3 and persists until F7. The organelle markers calnexin and succinate uniquinol-oxidoreductase are present in the outermost fraction, weakly present in F2 but absent from F3, suggesting that F2/F3 marks the boundary of the lens organelle-free zone. B, midsagittal section of a P3 mouse lens incubated with α-bdp1 antibody (green) or propidium iodide (red). Propidium-stained nuclei are present in the anterior epithelium and superficial fiber cells (see Fig. 1 for orientation). The position of the innermost nuclei marks the border of the OFZ. Calpain-cleaved spectrin is present in a diffuse, ∼100-μm-thick layer of cells bordering the OFZ. C, high magnification view of the regions (panels a–d) indicated in B. Panels a–d show α-bdp1 immunofluorescence. Panels a′–d′ show mAb1622 immunofluorescence. Note that unlike the intact molecule, calpain-cleaved spectrin is not associated with the fiber cell membranes. Scale bars, B, 150 μm; C,10 μm.

The progressive lysis technique yielded fractions from increasing depths within the lens. To relate the fractions to anatomical landmarks within the tissue, immunoblots were reprobed with antibodies against calnexin (an endoplasmic reticulum marker) or succinate ubiquinol-oxidoreductase (a mitochondrial marker). Both markers were present in F1 and F2 but absent thereafter. Mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum, and other organelles are degraded during lens fiber cell differentiation (34). The central region of the lens from which organelles have been removed is termed the organelle-free zone (OFZ). The coincident disappearance of the mitochondrial and endoplasmic reticulum markers indicated that fractions F2/F3 represented the border of the OFZ. Therefore, the disappearance of intact spectrin and the appearance of the calpain-cleaved fragment coincided with the degradation of the lens fiber organelles.

To confirm that calpain-mediated cleavage of αII-spectrin occurred at the time of organelle breakdown, Vibratome slices of P3 lenses were incubated with α-bdp1 or mAb1622 and counter-stained with propidium iodide to visualize the distribution of nuclei in the sections (Fig. 7B). In midsagittal sections, the α-bdp1 antibody labeled a layer of cortical fiber cells. The α-bdp1-positive layer spanned the border of the OFZ and included nucleated and anucleated fiber cells. The inner fiber cells were not labeled by the α-bdp1 antibody. A comparison between the staining pattern of α-bdp1 (which recognizes calpain-cleaved spectrin) and mAb1622 (which recognizes intact spectrin and/or fragments containing an intact C terminus) suggested that although intact spectrin remained associated with the plasma membrane in cortical fiber cells, calpain-cleaved spectrin redistributed into the cytosol (Fig. 7C).

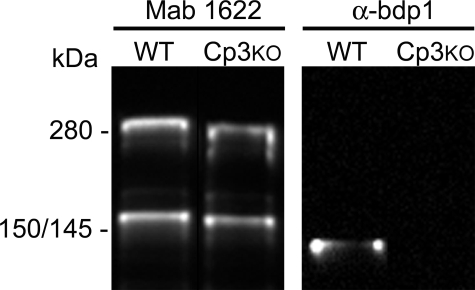

Of the four calpains detected in the lens (calpain 1, 2, 3, and 7), only the distribution of calpain 3 paralleled that of calpain-cleaved spectrin (compare Figs. 3 and 7). We reasoned that the functions of lens calpains might not be redundant and that based on its distribution, calpain 3 might be required for spectrin cleavage. Lens samples were obtained from calpain 3-null mice and analyzed by immunoblot. In homogenates from total lens, the bands corresponding to intact spectrin and the major 150-kDa breakdown product were observed in wild type and knock-out lenses (Fig. 8). As expected, the 139-kDa calpain-specific breakdown product was detected in samples from wild type lenses. However, the 139-kDa band was not detected in calpain 3-null lenses. Thus, calpain 3 is responsible for αII-spectrin cleavage at the QQEVY1176 1177GMMPR site, but spectrin is also cleaved independently at a nearby site by other proteases.

FIGURE 8.

Spectrin is cleaved by calpain 3 during lens fiber differentiation. Samples from wild type (WT, strain 129) or calpain 3-null lenses were probed with mAb1622 or αbdp1. Spectrin cleavage is evident in wild type or calpain 3-null lenses, but calpain-cleaved spectrin was only detected in the wild type lens samples.

DISCUSSION

As a consequence of its unusual growth pattern, the lens contains a record of cells produced at all stages of lens development. Cells of the inner strata are among the oldest in the body, whereas those located in the surface layers differentiated only recently. The coexistence of cells of different ages within a single tissue allows the fate of proteins to be charted by comparing the composition of the various strata. Such analysis has revealed that aging lens proteins undergo extensive posttranslational modification, including truncation. Proteomic studies have provided strong circumstantial evidence of a role for calpains in many truncation events. For example, multiple cleavage sites have been identified in the cytoplasmic, C-terminal, region of Aqp0, the most abundant lens membrane protein. Some of these sites may be due to calpain activity (52). Similarly, in vivo truncations of αA-crystallin at the C terminus have been tentatively ascribed to lp82 (calpain 3) and calpain 2 (53). Extensive N-terminal truncation of β-crystallins is observed in the lens nucleus and associated with progressive protein insolubilization. The pattern of cleavage products is similar to that obtained in vitro by digestion with calpain 2, suggesting a role for calpains in proteolysis of β-crystallins (54).

Here, we used two-dimensional DIGE to identify a set of calpain substrates in the lens membrane/cytoskeleton fraction. Spectrin is a well characterized calpain substrate in the lens and elsewhere. In cataractous lenses, under conditions of calcium overload, spectrin is known to be cleaved by calpain (55). However, in the present study, the use of the α-bdp1 antibody revealed that calpain-mediated spectrin cleavage also occurs during the course of normal fiber cell differentiation. The calpain-specific CQQEVY epitope first appears shortly before lens fiber cell organelle breakdown, signifying the activation of one or more calpains in the cortical region of the lens. This observation is consistent with the results of calpain activity assays conducted on cortical cell lysates (Fig. 4) and microinjection of calpain substrates into living cortical fiber cells (Fig. 5). Several of the other calpain substrates identified in the two-dimensional DIGE screen are also known to be degraded during fiber differentiation. For example, lengsin, a lens-specific glutamine synthetase, is synthesized late in fiber differentiation and rapidly degraded at the border of the OFZ (48). Vimentin and CP49, two members of the intermediate filament protein family, are also degraded during fiber cell differentiation. Vimentin is degraded shortly after organelle destruction, whereas CP49 is cleaved to a 40-kDa fragment that persists indefinitely (56). NrCam, a cell adhesion molecule, is an abundant component of the fiber cell plasma membrane in the lens cortex but is degraded in the central cells (57). The fact that many of the proteins identified in the two-dimensional DIGE screen are degraded during fiber differentiation suggests that calpains may be involved in their degradation. However, in each case, a more thorough knowledge of the nature of the cleavage products will be needed before a role for calpains can be established unequivocally.

The observation that calpain 1, 2, and 3 are expressed in the mouse lens is in agreement with earlier reports (58, 59). Calpain 7 (also known as PalBH) has not previously been detected in the lens, but its presence is not unexpected, as calpain 7 mRNA is widely expressed (60). Calpain 10 has been reported in the lens (42, 61), where it was found to be most abundant in new-born animals. This may explain why it was not detected in the present study, which utilized tissue from 4–6-week-old mice.

A novel observation in the current study was that, unlike other lens calpains, calpain 3 is not expressed in the outer cell layers but, rather, in the midcortical and core regions of the lens. This is consistent with previously reported immunocytochemistry results of calpain expression in the mouse lens (42) and the present study for spectrin. The distribution pattern of calpain 3 thus coincides spatially with the cleavage of spectrin. Further, in samples from calpain 3-null animals, the calpain-specific CQQEVY epitope was not generated, suggesting that calpain 3 is responsible for cleavage of spectrin at this site. Both calpain 1 and calpain 2 are able to cleave spectrin between Tyr1176 and Gly1177. The finding that spectrin is not cleaved at this site in calpain 3-null lenses suggests that only calpain 3 is activated during fiber cell differentiation.

Unlike calpain 1 and 2, calpain 3 is relatively insensitive to inhibition by calpastatin, the endogenous calpain inhibitor. Furthermore, the calcium requirement for half-maximal activation of calpain 3 is 20 μm (62), lower than that for calpain 1 and 2. These characteristics, together with the different depth localization of the other calpains, could explain why calpain 3 is activated in the lens cortex, whereas calpain 1 and 2 are apparently not.

Spectrin is cleaved into large fragments in cells bordering the OFZ. Calpain 3 cleaves spectrin between Tyr1176 and Gly1177. However, this is not the only cleavage site. In the absence of calpain 3, a similarly sized C-terminal fragment is generated, indicating the presence of another protease(s) that cleave spectrin close to the calpain-specific site. Previous studies on spectrin fragmentation during chicken embryo lens development have suggested that spectrin is cleaved by caspase 3 (63), and indeed, the caspase 3 cleavage site is within 9 amino acids of the calpain site. However, spectrin cleavage in lenses from caspase-3-deficient mice is indistinguishable from wild type (data not shown), indicating that caspase 3 does not play an indispensable role in the mouse lens. It should be noted, however, that caspase 7, is also expressed in the lens and shares the DXXD↓S caspase 3 consensus cleavage site. Thus, it remains possible that caspases contribute to spectrin degradation during fiber formation.

The spectrin-actin submembrane scaffold provides direct mechanical support to the phospholipid bilayer. Cleavage of αII-spectrin is expected to eliminate its capacity to bind actin and thereby disrupt the connection between the plasma membrane and the cytoskeleton. Such an effect might underlie the dramatic remodeling of the plasma membrane that occurs during fiber cell maturation, when the cell surfaces are thrown into a complex series of interlocking folds. Similarly, cell maturation involves the formation of fusion pores between adjacent fiber cells. This occurs in cells located in the midcortex of the lens, the same zone in which spectrin cleavage is first noted. Calpain-mediated cleavage of the submembrane cytoskeleton is essential for successful fusion of erythrocytes (64) or myoblasts (12) and might also be important in the lens.

The appearance of calpain-cleaved spectrin coincides temporally and spatially with the onset of organelle degradation. The coordinated removal of organelles during lens fiber cell differentiation presumably requires the regulated activity of one or more proteolytic systems. Calpain 3 is the first protease shown to be activated in cells bordering the OFZ. One organelle component, ATP synthase β (a component of the F1 portion of the synthase located at the inner mitochondrial membrane), was among the 12 calpain substrates identified in the two-dimensional DIGE screen. This raises the intriguing possibility that calpain activation in cells bordering the OFZ contributes directly to the dissolution of fiber cell organelles. It is possible, however, that calpain activation is a consequence of organelle breakdown rather than its cause. Thus, because mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum represent two major cellular calcium stores, it is expected that their disintegration will cause a spike in intracellular calcium that could trigger calpain activity. A careful morphological evaluation of lenses from calpain 3-null mice will help resolve these and other issues.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Calpain 3-null mice were kindly provided by Isabelle Richards (Généthon,Évry, France). Tom Shearer and Hong Ma (Oregon Health Sciences University, Portland, OR) generously provided antibodies against calpain 3 (lp82/85) and calpain 10. The antibody against calpain-cleaved αII spectrin (α-bdp1) was a gift from Jon Morrow (Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT). Paul Fitzgerald (University of California, Davis) provided helpful advice on the preparation of lens membrane/cytoskeleton fractions. We thank Seta Dikranian for excellent technical support.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant P30 NS057105 (to Washington University). This work was also supported by Grant R01EY09852 (to S. B.), Core Grant for Vision Research EY02687, an unrestricted grant to the Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences from Research to Prevent Blindness (to Washington University), and Core Grant EY01792 to the Department of Ophthalmology of the University of Illinois at Chicago.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental data.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; Cy3, 1-(5-carboxypentyl)-1′-propylindocarbocyanine halide N-hydroxysuccinimidyl ester; Cy5, 1-(5-carboxypentyl)-1′-methylindodicarbocyanine halide N-hydroxysuccinimidyl ester; DIGE, difference gel electrophoresis; Pn, postnatal day n; mAb, monoclonal antibody; OFZ, organelle-free zone.

References

- 1.Croall, D. E., and Ersfeld, K. (2007) Genome Biol. 8 218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arthur, J. S., Elce, J. S., Hegadorn, C., Williams, K., and Greer, P. A. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 20 4474-4481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zimmerman, U. J., Boring, L., Pak, J. H., Mukerjee, N., and Wang, K. K. (2000) IUBMB Life 50 63-68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dutt, P., Croall, D. E., Arthur, J. S., Veyra, T. D., Williams, K., Elce, J. S., and Greer, P. A. (2006) BMC Dev. Biol. 6 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanis, C. L., Boerwinkle, E., Chakraborty, R., Ellsworth, D. L., Concannon, P., Stirling, B., Morrison, V. A., Wapelhorst, B., Spielman, R. S., Gogolin-Ewens, K. J., Shepard, J. M., Williams, S. R., Risch, N., Hinds, D., Iwasaki, N., Ogata, M., Omori, Y., Petzold, C., Rietzch, H., Schroder, H. E., Schulze, J., Cox, N. J., Menzel, S., Boriraj, V. V., Chen, X., Lim, L. R., Lindner, T., Mereu, L. E., Wang, Y. Q., Xiang, K., Yamagata, K., Yang, Y., and Bell, G. I. (1996) Nat. Genet. 13 161-166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horikawa, Y., Oda, N., Cox, N. J., Li, X., Orho-Melander, M., Hara, M., Hinokio, Y., Lindner, T. H., Mashima, H., Schwarz, P. E., del Bosque-Plata, L., Horikawa, Y., Oda, Y., Yoshiuchi, I., Colilla, S., Polonsky, K. S., Wei, S., Concannon, P., Iwasaki, N., Schulze, J., Baier, L. J., Bogardus, C., Groop, L., Boerwinkle, E., Hanis, C. L., and Bell, G. I. (2000) Nat. Genet. 26 163-175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu, J., Liu, M. C., and Wang, K. K. (2008) Sci. Signal. 1 re1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu, X., and Schnellmann, R. G. (2003) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 304 63-70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sato, K., and Kawashima, S. (2001) Biol. Chem. 382 743-751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hell, J. W., Westenbroek, R. E., Breeze, L. J., Wang, K. K., Chavkin, C., and Catterall, W. A. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93 3362-3367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bi, X., Chang, V., Molnar, E., McIlhinney, R. A., and Baudry, M. (1996) Neuroscience 73 903-906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barnoy, S., Maki, M., and Kosower, N. S. (2005) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 332 697-701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tomimatsu, Y., Idemoto, S., Moriguchi, S., Watanabe, S., and Nakanishi, H. (2002) Life Sci. 72 355-361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dourdin, N., Bhatt, A. K., Dutt, P., Greer, P. A., Arthur, J. S., Elce, J. S., and Huttenlocher, A. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 48382-48388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nixon, R. A., Saito, K. I., Grynspan, F., Griffin, W. R., Katayama, S., Honda, T., Mohan, P. S., Shea, T. B., and Beermann, M. (1994) Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 747 77-91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Biswas, S., Harris, F., Dennison, S., Singh, J., and Phoenix, D. A. (2004) Trends Mol. Med. 10 78-84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh, R. B., Dandekar, S. P., Elimban, V., Gupta, S. K., and Dhalla, N. S. (2004) Mol. Cell. Biochem. 263 241-256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vosler, P. S., Brennan, C. S., and Chen, J. (2008) Mol. Neurobiol. 38 78-100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sorimachi, H., Ishiura, S., and Suzuki, K. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268 19476-19482 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee, H. J., Sorimachi, H., Jeong, S. Y., Ishiura, S., and Suzuki, K. (1998) Biol. Chem. 379 175-183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sorimachi, H., Imajoh-Ohmi, S., Emori, Y., Kawasaki, H., Ohno, S., Minami, Y., and Suzuki, K. (1989) J. Biol. Chem. 264 20106-20111 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herasse, M., Ono, Y., Fougerousse, F., Kimura, E., Stockholm, D., Beley, C., Montarras, D., Pinset, C., Sorimachi, H., Suzuki, K., Beckmann, J. S., and Richard, I. (1999) Mol. Cell. Biol. 19 4047-4055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakajima, T., Fukiage, C., Azuma, M., Ma, H., and Shearer, T. R. (2001) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1519 55-64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shih, M., David, L. L., Lampi, K. J., Ma, H., Fukiage, C., Azuma, M., and Shearer, T. R. (2001) Curr. Eye Res. 22 458-469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Azuma, M., Fukiage, C., David, L. L., and Shearer, T. R. (1997) Exp. Eye Res. 64 529-538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakamura, Y., Fukiage, C., Shih, M., Ma, H., David, L. L., Azuma, M., and Shearer, T. R. (2000) Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 41 1460-1466 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sakamoto-Mizutani, K., Fukiage, C., Tamada, Y., Azuma, M., and Shearer, T. R. (2002) Exp. Eye Res. 75 611-617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fukiage, C., Azuma, M., Nakamura, Y., Tamada, Y., Nakamura, M., and Shearer, T. R. (1997) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1361 304-312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Biswas, S., Harris, F., Singh, J., and Phoenix, D. A. (2004) Mol. Cell. Biochem. 261 169-173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tamada, Y., Fukiage, C., Mizutani, K., Yamaguchi, M., Nakamura, Y., Azuma, M., and Shearer, T. R. (2001) Curr. Eye Res. 22 280-285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robertson, L. J., Morton, J. D., Yamaguchi, M., Bickerstaffe, R., Shearer, T. R., and Azuma, M. (2005) Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 46 4634-4640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blankenship, T., Bradshaw, L., Shibata, B., and Fitzgerald, P. (2007) Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 48 3269-3276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shestopalov, V. I., and Bassnett, S. (2003) J. Cell Sci. 116 4191-4199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bassnett, S. (2008) Exp. Eye Res. 88 133-139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang, Y., Liu, X., Zoltoski, R. K., Herrera, R. A., Richrd, I., Kuszak, J. R., and Kumar, N. M. (2007) Investig. Ophthalm. Vis. Sci. 48 2685-2694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leonard, J. R., Klocke, B. J., D'Sa, C., Flavell, R. A., and Roth, K. A. (2002) J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 61 673-677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Richard, I., Roudaut, C., Marchand, S., Baghdiguian, S., Herasse, M., Stockholm, D., Ono, Y., Suel, L., Bourg, N., Sorimachi, H., Lefranc, G., Fardeau, M., Sebille, A., and Beckmann, J. S. (2000) J. Cell Biol. 151 1583-1590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ma, H., Shih, M., Hata, I., Fukiage, C., Azuma, M., and Shearer, T. R. (1998) Exp. Eye Res. 67 221-229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Glantz, S. B., Cianci, C. D., Iyer, R., Pradhan, D., Wang, K. K., and Morrow, J. S. (2007) Biochemistry 46 502-513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pierscionek, B., and Augusteyn, R. C. (1988) Curr. Eye Res. 7 11-23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bredemeyer, A. J., Lewis, R. M., Malone, J. P., Davis, A. E., Gross, J., Townsend, R. R., and Ley, T. J. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101 11785-11790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reed, N. A., Castellini, M. A., Ma, H., Shearer, T. R., and Duncan, M. K. (2003) Exp. Eye Res. 76 433-443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ma, H., Hata, I., Shih, M., Fukiage, C., Nakamura, Y., Azuma, M., and Shearer, T. R. (1999) Exp. Eye Res. 68 447-456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shearer, T. R., Azuma, M., David, L. L., and Murachi, T. (1991) Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 32 533-540 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bagchi, M., Caporale, M. J., Wechter, R. S., and Maisel, H. (1985) Exp. Eye Res. 40 385-392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Merdes, A., Brunkener, M., Horstmann, H., and Georgatos, S. D. (1991) J. Cell Biol. 115 397-410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ireland, M., and Maisel, H. (1984) Exp. Eye Res. 38 637-645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wyatt, K., Gao, C., Tsai, J. Y., Fariss, R. N., Ray, S., and Wistow, G. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283 6607-6615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Repasky, E. A., Granger, B. L., and Lazarides, E. (1982) Cell 29 821-833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Czogalla, A., and Sikorski, A. F. (2005) Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 62 1913-1924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roberts-Lewis, J. M., Savage, M. J., Marcy, V. R., Pinsker, L. R., and Siman, R. (1994) J. Neurosci. 14 3934-3944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ma, H., Azuma, M., and Shearer, T. R. (2005) FEBS Lett. 579 6745-6748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ueda, Y., Fukiage, C., Shih, M., Shearer, T. R., and David, L. L. (2002) Mol. Cell. Proteomics 1 357-365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.David, L. L., Azuma, M., and Shearer, T. R. (1994) Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 35 785-793 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Truscott, R. J., Marcantonio, J. M., Tomlinson, J., and Duncan, G. (1989) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 162 1472-1477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sandilands, A., Prescott, A. R., Carter, J. M., Hutcheson, A. M., Quinlan, R. A., Richards, J., and FitzGerald, P. G. (1995) J. Cell Sci. 108 1397-1406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.More, M. I., Kirsch, F. P., and Rathjen, F. G. (2001) J. Cell Biol. 154 187-196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yoshida, H., Murachi, T., and Tsukahara, I. (1985) Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 26 953-956 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ma, H., Fukiage, C., Azuma, M., and Shearer, T. R. (1998) Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 39 454-461 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Futai, E., Kubo, T., Sorimachi, H., Suzuki, K., and Maeda, T. (2001) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1517 316-319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ma, H., Fukiage, C., Kim, Y. H., Duncan, M. K., Reed, N. A., Shih, M., Azuma, M., and Shearer, T. R. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 28525-28531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shih, M., Ma, H., Nakajima, E., David, L. L., Azuma, M., and Shearer, T. R. (2006) Exp. Eye Res. 82 146-152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lee, A., Morrow, J. S., and Fowler, V. M. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 20735-20742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Glaser, T., and Kosower, N. S. (1986) FEBS Lett. 206 115-120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.