Abstract

Case-control association studies often aim to investigate the role of genes and gene-environment interactions in terms of the underlying haplotypes (i.e., the combinations of alleles at multiple genetic loci along chromosomal regions). The goal of this article is to develop robust but efficient approaches to the estimation of disease odds-ratio parameters associated with haplotypes and haplotype-environment interactions. We consider “shrinkage” estimation techniques that can adaptively relax the model assumptions of Hardy-Weinberg-Equilibrium and gene-environment independence required by recently proposed efficient “retrospective” methods. Our proposal involves first development of a novel retrospective approach to the analysis of case-control data, one that is robust to the nature of the gene-environment distribution in the underlying population. Next, it involves shrinkage of the robust retrospective estimator toward a more precise, but model-dependent, retrospective estimator using novel empirical Bayes and penalized regression techniques. Methods for variance estimation are proposed based on asymptotic theories. Simulations and two data examples illustrate both the robustness and efficiency of the proposed methods.

Keywords: Empirical Bayes, Genetic epidemiology, LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator), Model averaging, Model robustness, Model selection

1. INTRODUCTION

Haplotypes, the combinations of alleles at multiple loci along individual homologous chromosomes, define the functional units of a gene through which the underlying protein product is made (Clark 2004). Association studies based on haplotypes, which can capture interloci interactions as well as “indirect association” due to linkage disequilibrium (LD) with unobserved causal variants, can be a powerful approach to the discovery and characterization of the genetic basis of complex diseases (Schaid 2004). Thus, in recent years, there has been tremendous interest in developing methods for haplotype-based regression analysis of genetic epidemiologic data. A technical problem has been that traditional epidemiologic studies only collect locus-specific genotype data, which does not provide the “phase information”, that is, which alleles appear at multiple loci along the individual chromosomes. Statistically, the lack of phase information can be viewed as a special missing data problem.

For logistic regression analysis of unmatched case-control studies, two classes of methods have evolved. The “prospective” methods (Schaid, Rowland, Tines, Jacobson, and Polalnd 2002; Zhao, Li, and Khalid 2003; Lake et al. 2003) ignore the underlying retrospective nature of the case-control design. These methods are considered robust in the sense that they depend very weakly on the underlying assumptions of Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) and gene-environment (G-E) independence, although the assumptions cannot be totally avoided because of the phase ambiguity problem. In contrast, “retrospective” methods (Epstein and Satten 2003; Stram et al. 2003; Satten and Epstein 2004; Spinka, Carroll, and Chatterjee 2005; Lin and Zeng 2006), which properly account for case-control sampling, can fully exploit the assumptions of HWE and G-E independence to gain major efficiency over the prospective methods. It is often debatable which of the two types of methods is more suitable for a particular study. Prospective estimates of haplotype-effects and haplotype-environment interactions involving relatively rare haplotypes often tend to be very imprecise. Retrospective methods can produce much more precise estimates of those parameters, but concern often remains about the potential for bias because of the possible violation of the underlying assumptions, a potential we see in our simulations.

The potential for bias in retrospective methods can be reduced by flexible modeling approaches that relax the underlying assumptions. Alternative population genetic models that can relax the HWE assumptions have been used for retrospective haplotype analysis of case-control data (Satten and Epstein 2004; Lin and Zeng 2006). It has been also shown that the assumption of G-E independence can be relaxed to a large extent by assuming haplotypes are independent of E given unphased genotypes, but allowing the conditional distribution of E given the unphased genotypes to remain completely unrestricted (Lin and Zeng 2006). These solutions, which can alleviate the concern about bias, are not completely satisfactory. First, models for relaxing the HWE assumption can capture only certain types of departures from the underlying constraints for the diplotype distribution and may not be able to model phenomena such as excess heterozygosity. Second, even if a completely nonparametric model for the G-E distribution is available, we may still be able to gain efficiency in analysis of case-control data by exploiting the fact that HWE and G-E independence often do hold, approximately if not exactly. In the existing methods, if one uses a very general model for the distribution of G-E, then the concern about bias will be minimized, but inevitably efficiency will be lost.

Our main objective is to develop methods for haplotype-based analysis of case-control studies, which can gain efficiency by exploiting model assumptions of HWE and G-E independence for the underlying population and yet are resistant to bias when those model assumptions are violated. The basic idea involves shrinkage of a “model-free” estimator that is robust to HWE and G-E independence toward a “model-based” estimator that directly exploits those assumptions. The amount of “shrinkage” is sample size and data adaptive so that in large samples the method has no bias whether the assumptions of HWE and G-E independence hold, and yet the method can gain efficiency by shrinking the analysis toward HWE and G-E independence, but only to the extent the data validates the assumptions.

There are several novel aspects of our proposal. First, in Section 2.2, we propose a novel retrospective likelihood approach to haplotype analysis of case-control data that is robust to the nature of the gene-environment distribution in the underlying population. Second, in Section 3, we develop an empirical Bayes (EB)-type shrinkage estimation approach and a rigorous asymptotic theory for it. The key difficulty is that the problem is semiparametric, in that there are infinite-dimensional nuisance parameters associated with the joint distribution of the gene and the environment. Our method overcomes this difficulty by focusing only on the parameters of interest. In Section 4, we develop a penalized likelihood approach and asymptotic theory for it. The penalized likelihood involves shrinkage, not of a parameter or set of parameters to zero as is usually done, but to a model-based estimator, and also overcomes the problem of infinite-dimensional nuisance parameters. Effectively, we try to shrink the difference of the model-free and model-based estimators toward zero. In Sections 5 and 6, we use simulation studies and two real data examples to illustrate that unlike the existing haplotype-based regression methods, whose utility depends crucially on specific model assumptions, the proposed shrinkage methods adapt themselves to a wide range of situations.

Finally, although our scientific focus of this article is haplotype-based case-control studies, this article makes a far more general contribution. Using modern shrinkage and penalization techniques to combine assumption-laden and assumption-free methods in semiparametric problems with infinite dimensional nuisance parameters is an idea that transcends genetic association studies. We hope that our article will lead to further research in this more general area.

2. A MODEL-BASED AND A MODEL-FREE ESTIMATOR

Let H = (Ha, Hb) denote the diplotype status (haplotype pair) for a subject at M loci of interest within a genomic region. Given H and a set of environmental covariates, X, assume that the risk of a binary disease outcome D is given by the logistic regression model

| (1) |

where m(·) is a known but arbitrary function that specifies the log-odds-ratio of the disease as a function of H and X in terms of a set of regression parameters β1 . In (1), the effect of a diplotype can be further specified in terms of the effect of the constituent haplotypes assuming dominant, recessive, or additive modes of penetrance (Wallenstein, Hodge, and Weston 1998). Let G = (g1, . . ., gM) denote the unphased genotype data for the M loci. As explained earlier, the genotype data G could be consistent with multiple diplotypes because of phase ambiguity. We denote to be the set of all possible diplotypes that are consistent with the genotype data G. Let F(X, G) be the cumulative distribution function for X and G in the underlying population.

Assume data on G and X are collected in a case-control study for N0 controls (D = 0) and N1 cases (D = 1). Let N = N0 + N1. The fundamental likelihood for case-control data, known as the “retrospective” likelihood, is given by

| (2) |

where the last expression follows by Bayes theorem and the identity that

2.1 A Model-Based Framework

First, let us consider obtaining a “model-based” estimator for β1 under the assumption that H and X are independent and that the distribution of H follows HWE in the underlying population. Under these assumptions, the joint density function for X and G is

| ( 3 ) |

where F(X) is the marginal distribution function for , and pr(H) is the population frequency of the diplotype H. Under HWE for haplotypes, we have

where θs denotes the population frequency for the haplotype hs. Under the hapotype-environment (H-X) independence, we also have

| ( 4 ) |

Spinka et al. (2005) showed how to estimate β and θ by maximization of the retrospective likelihood (2) under HWE and the H-X independence, while allowing F(X) to remain completely unrestricted, using a computationally simple “profile-likelihood” approach, see also (6) later. This forms the “model-based” approach.

2.2 A Model-Free Framework

Now consider obtaining a “model-free” estimator. Unfortunately, in the presence of phase ambiguity, β and θ are not identifiable from the retrospective likelihood (2) if the joint distribution of X and H is left completely unrestricted (e.g., see Epstein and Satten 2003; Lin and Zeng 2006). We propose to resolve this identifiability issue by making minimal distributional assumptions. We note that, given that X and G are directly observed, the joint distribution function dF(X, G) should be estimable nonparametrically, even though the joint distribution of X and H is not. Thus, β1 should be identifiable from (2) with some constraints on the conditional distribution of H given G and X. We propose to use HWE and H-X independence constraints to specify the conditional distribution pr(H|G, X) [i.e., instead of (3) we assume only that (4) holds]. Lin and Zeng (2006) used a similar approach to allow the conditional distribution of pr(X|G) to be completely unrestricted, but they essentially imposed HWE or related population genetics model constraints not only on pr(H|G), but also on pr(G). Our method can allow the marginal distribution pr(G) to remain completely unrestricted and thus is even more robust.

To see why (4) involves very mild assumptions, note that if there were no phase ambiguity (i.e., G = H), then this formulation does not impose any restriction on the population distribution of the covariates of the logistic regression model (1). In this case, it follows from classical theory (Prentice and Pyke 1979) that the retrospective maximum-likelihood estimate of β1 could be obtained using standard prospective logistic regression analysis, the validity of which does not depend on assumptions for the covariate distribution. In contrast, the validity of Lin and Zeng's estimator does depend on the assumed diplotype distribution.

In the presence of phase ambiguity, violation of HWE and H-X independence for the underlying population would imply that the corresponding constraint for the distribution pr(H|X, G) will also not hold. However, in typical association studies involving tightly linked loci, the problem of phase ambiguity tends to be modest and the misspecification of the conditional distribution in such situations will have a fairly small influence on inference on the regression parameters in our model-free framework, see Section 5 for simulation results.

2.3 ESTIMATORS

2.3.1 The Model-Free Estimator

We next develop an algorithm for obtaining the semiparametric maximum likelihood estimator of β1, one that maximizes the retrospective likelihood (2) under the assumption (4), allowing F(G, X) to remain completely nonparametric. We consider a profile-likelihood approach analogous to that described in Chatterjee and Carroll (2005), Spinka et al. (2005) and Chatterjee and Chen (2007). In particular, assuming that the nonparametric maximum likelihood estimator of F(X, G) allows masses only on the observed data points, following arguments analogous to Spinka et al. we can show that the estimator of β1, which maximizes the retrospective likelihood (2), can be obtained from an alternative pseudo-likelihood of the data where the contribution of each subject is given by

| ( 5 ) |

where qfree(h|G, θ) denotes pr(H|G), computed according to (4), and

pd = Nd/N, πd = pr(D = d), κ = β0 + log(p1/p0) − log(π1/π0), and Ω = (β0, β1, θ, κ). Under a rare disease assumption, , β0 is not identifiable and Ω no longer contains β0.

Note that Lfree(D, G, X, Ω) will contain little information on θ, because it conditions on G. Thus, when implementing methods based on this likelihood, we replace the score function for θ by the estimating function for θ based on the genotype data from the controls and the HWE assumption. It can be seen that, when using such an estimating function for θ and the rare disease approximation mentioned previously, the estimator obtained from the retrospective likelihood Lfree(D, G, X, Ω) is equivalent to that from the prospective approach proposed by Zhao et al. (2003).

2.3.2 The Model-Based Estimator

We note that the profile-likelihood estimator Spinka et al. (2005) derived for maximization of (2) under the assumptions of HWE and H-X independence corresponds to a pseudo-likelihood where the contribution of each subject is given by

| ( 6 ) |

where q(h; θ) denotes pr(H = h) computed according to HWE.

2.3.3 An Alternative Characterization

Interestingly, the pseudo-likelihoods for both the “model-based” and the “model-free” estimators can be derived as a proper likelihood under an alternative sampling design, wherein a case-control study can be viewed as a prospective study with missing data. Consider a sampling scenario where each subject from the underlying population is selected into the case-control study using a Bernoulli sampling scheme where the selection probability for a subject given his or her disease status D = d is proportional to μd = Nd/pr(D = d). Let R = 1 denote the indicator of whether a subject is selected in the case-control sample under this Bernoulli sampling scheme and hence has been observed. Under this sampling scheme, it is easy to show that

The proof for the former identity can be found in Spinka et al. (2005) and that for the latter identity follows similarly. Thus, in this alternative sampling scheme, the difference between the model-based and model-free estimators corresponds to whether the genotype data has been conditioned out of the likelihood or not.

As discussed in Chatterjee and Carroll (2005), in a case-control sample, it may be difficult to estimate the intercept parameter b0 even when the haplotype-environment independence assumption is imposed. However, the estimation of b0 can be avoided by imposing the rare-disease assumption so that the parameters in effect are (k, β1, θ). In the following discussion, we will adopt this convention and redefine the regression parameters β = (k, β1).

3. EMPIRICAL BAYES-TYPE SHRINKAGE ESTIMATORS

Once we obtain two estimators of β, we propose to combine them using EB-type weighting in the spirit of Mukherjee and Chatterjee (2008). Previously, we have developed a general theory for obtaining such weighted estimators when the departure of the population distribution of the risk-factors from the underlying models can be indexed by a finite set of parameters. In the current setting, however, the departure of the nonparametric density dF(X, G) from the restricted density cannot be indexed by a fixed set of parameters. Thus, we propose constructing the EB-type shrinkage estimator directly in terms of the focus parameters of interest, namely β, rather than both β and the nuisance parameters θ.

Let βfree and βmodel denote the asymptotic limit of model-free and model-based estimators proposed previously. Note that when HWE and (G-E) independence hold, we have ψ = βmodel – βfree = 0. Thus, if we want to relax this assumption, we can use a stochastic framework where we assume and note that is a conservative estimate of Υ, conservative in the sense that its mean is greater than Υ (a matrix A is defined as greater than a matrix B when A – B is semi-positive definite). Define a shrinkage factor given by the matrix

where V is the (estimated) variance-covariance matrix of . By this logic, we can construct an EB-type estimator

| ( 7 ) |

We observe that Equation (7) suggests a general way of constructing simple shrinkage estimators. The shrinkage factor K determines the amount of shrinkage of the model-free estimator toward its model-based counterpart, with the two extremes being K = I (identity matrix) implying and K = 0 implying . If the estimator is to be approximately consistent in large samples, whether the HWE and (G-E) independence assumptions hold or not, the matrix K should go to zero, at least when βmodel ≠ βfree, as sample size increases. Moreover, if K goes to zero at a suitable rate, can be asymptotically equivalent to the model-free estimator, but in finite samples and when the difference between βmodel and βfree is small, which might often be the case in practice, then can still have better finite sample performance in terms of the bias-variance trade-off. Simulation results in Section 5 will illustrate this feature. It is intuitive that K should be such that more weight should be given to or depending on the bias of the model-based estimator, a quantity that can be estimated empirically as . In Sections 5 and 6, we will also consider one such alternative EB-type shrinkage estimator where we choose K to be a diagonal matrix with the ith diagonal element being , where νi is the ith diagonal element of V and is the ith component of .

3.1 Asymptotic Theory

When the assumptions of HWE or H-X independence or both are violated so that βmodel ≠ βfree, it is easy to show that the EB estimator is asymptotically equivalent to , and hence is consistent for β (see Appendix C). Nevertheless, utilizing the bias-variance trade-offs between and , the EB estimator we propose can have substantially better finite sample properties than the model-free estimator βfree (see Tables 2 and 3; see also Section 5 for simulation details). Moreover, using the δ-method, in Appendix C we derive an approximate covariance matrix estimator for the EB estimator, which is found to be more accurate in finite samples than the “naïve” covariance estimator obtained by the covariance matrix of the asymptotically equivalent model-free estimator.

Table 2.

MSE (bias in parenthesis) over 1,000 simulations: dominant model

|

N1 = N0 = 150 |

N1 = N0 = 300 |

N1 = N0 = 600 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSE (bias) |

MSE (bias) |

MSE (bias) |

|||||

| H | H × X | H | H × X | H | H × X | ||

| f = 0 | 0.10 (0.00) | 0.34 (0.01) | 0.05 (0.00) | 0.16 (0.05) | 0.03 (0.00) | 0.07 (0.00) | |

| γ1,3 = 0 | 0.07 (0.00) | 0.13 (−0.04) | 0.04 (0.00) | 0.07 (−0.02) | 0.02 (0.00) | 0.04 (−0.04) | |

| 0.08 (0.00) | 0.14 (−0.04) | 0.04 (−0.01) | 0.07 (−0.01) | 0.02 (0.00) | 0.04 (−0.04) | ||

| 0.10 (0.00) | 0.32 (0.00) | 0.05 (0.00) | 0.15 (0.04) | 0.03 (0.00) | 0.07 (0.00) | ||

| 0.09 (−0.01) | 0.23 (0.00) | 0.04 (0.00) | 0.11 (0.03) | 0.02 (0.00) | 0.05 (−0.01) | ||

| 0.08 (0.00) | 0.19 (−0.01) | 0.04 (0.00) | 0.10 (0.03) | 0.02 (0.00) | 0.05 (−0.02) | ||

| |

|

0.09 (0.00) |

0.24 (0.00) |

0.05 (0.00) |

0.14 (0.04) |

0.03 (0.00) |

0.06 (0.00) |

| f = 0.05 | 0.11 (−0.01) | 0.34 (0.06) | 0.05 (0.00) | 0.17 (0.02) | 0.02 (−0.02) | 0.06 (0.03) | |

| γ1,3 = 0 | 0.09 (−0.12) | 0.14 (−0.02) | 0.05 (−0.12) | 0.07 (−0.03) | 0.03 (−0.13) | 0.03 (−0.03) | |

| 0.08 (0.00) | 0.14 (−0.02) | 0.04 (0.01) | 0.07 (−0.03) | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.03 (−0.03) | ||

| 0.11 (−0.02) | 0.31 (0.05) | 0.05 (−0.01) | 0.16 (0.02) | 0.02 (−0.03) | 0.06 (0.03) | ||

| 0.10 (−0.05) | 0.23 (0.03) | 0.05 (−0.03) | 0.12 (0.00) | 0.02 (−0.05) | 0.05 (0.01) | ||

| 0.09 (−0.07) | 0.20 (0.03) | 0.05 (−0.05) | 0.11 (0.01) | 0.02 (−0.04) | 0.05 (0.02) | ||

| |

|

0.10 (−0.03) |

0.25 (0.04) |

0.05 (−0.01) |

0.14 (0.01) |

0.02 (−0.03) |

0.06 (0.02) |

| f = 0 | 0.11 (0.01) | 0.37 (0.03) | 0.06 (0.00) | 0.17 (0.03) | 0.02 (0.00) | 0.07 (0.02) | |

| γ1, 3=−0.4 | 0.11 (0.17) | 0.35 (−0.46) | 0.07 (0.16) | 0.27 (−0.45) | 0.05 (0.17) | 0.26 (−0.48) | |

| 0.12 (0.17) | 0.36 (−0.46) | 0.07 (0.16) | 0.28 (−0.46) | 0.05 (0.16) | 0.26 (−0.48) | ||

| 0.11 (0.01) | 0.35 (0.00) | 0.05 (0.01) | 0.16 (0.06) | 0.02 (0.00) | 0.07 (0.00) | ||

| 0.10 (0.06) | 0.32 (−0.11) | 0.05 (0.04) | 0.17 (−0.09) | 0.02 (0.03) | 0.08 (−0.05) | ||

| 0.10 (0.09) | 0.29 (−0.16) | 0.05 (0.06) | 0.16 (−0.09) | 0.02 (0.03) | 0.07 (−0.04) | ||

| |

|

0.10 (0.04) |

0.31 (−0.06) |

0.05 (0.02) |

0.16 (−0.02) |

0.02 (0.00) |

0.07 (0.01) |

| f = 0.05 | 0.11 (−0.03) | 0.33 (0.10) | 0.05 (−0.00) | 0.16 (−0.01) | 0.03 (0.00) | 0.07 (0.00) | |

| γ1,3=−0.4 | 0.09 (0.04) | 0.36 (−0.46) | 0.04 (0.05) | 0.28 (−0.46) | 0.02 (0.05) | 0.26 (−0.48) | |

| 0.12 (0.17) | 0.38 (−0.48) | 0.07 (0.16) | 0.28 (−0.46) | 0.05 (0.17) | 0.26 (−0.48) | ||

| 0.11 (−0.03) | 0.31 (0.07) | 0.05 (0.00) | 0.16 (−0.02) | 0.03 (0.00) | 0.07 (−0.02) | ||

| 0.10 (−0.01) | 0.28 (−0.06) | 0.04 (0.01) | 0.16 (−0.11) | 0.02 (0.02) | 0.08 (−0.08) | ||

| 0.09 (0.00) | 0.25 (−0.10) | 0.05 (0.01) | 0.15 (−0.11) | 0.02 (0.00) | 0.07 (−0.05) | ||

| 0.10 (−0.02) | 0.27 (0.00) | 0.05 (0.00) | 0.15 (−0.04) | 0.03 (0.00) | 0.07 (−0.02) | ||

NOTE: : model-based estimator; : model-free estimator; : estimator accounting for Hardy-Weinberg disequilibrium; and : multivariate and component-wise empirical-Bayes estimators; and : L1 and L2 penalized estimators. Here f is the fixation index quantifying departures from HWE, and γ1, 3 quantifies departures from gene-environment independence. HWE is f = 0, and G-E independence is γ1, 3 = 0. Monte Carlo standard errors of MSEs (biases) in the table range from 0.001−0.016 (0.004−0.019).

Table 3.

MSE (bias in parenthesis) over 1,000 simulations: recessive model.

|

N1 = N0 = 300 |

N1 = N0 = 600 |

N1 = N0 = 1,000 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSE (bias) |

MSE (bias) |

MSE (bias) |

|||||

| H | H × X | H | H × X | H | H × X | ||

| f = 0 | 0.15 (0.03) | 0.59 (0.04) | 0.08 (−0.01) | 0.26 (0.02) | 0.05 (0.01) | 0.14 (0.00) | |

| γ1,3 = 0 | 0.09 (−0.01) | 0.20 (−0.07) | 0.04 (−0.03) | 0.10 (−0.05) | 0.03 (−0.01) | 0.05 (−0.04) | |

| 0.10 (−0.04) | 0.20 (−0.03) | 0.04 (−0.03) | 0.10 (−0.06) | 0.03 (−0.01) | 0.05 (−0.04) | ||

| 0.12 (0.01) | 0.43 (0.01) | 0.06 (−0.01) | 0.20 (0.00) | 0.04 (0.01) | 0.11 (−0.02) | ||

| 0.12 (0.01) | 0.39 (−0.01) | 0.06 (−0.02) | 0.17 (−0.01) | 0.04 (0.01) | 0.10 (−0.02) | ||

| 0.11 (0.00) | 0.37 (0.00) | 0.06 (−0.01) | 0.18 (−0.01) | 0.04 (0.01) | 0.11 (−0.02) | ||

| |

|

0.12 (0.02) |

0.43 (0.00) |

0.07 (−0.01) |

0.22 (0.00) |

0.05 (0.01) |

0.13 (−0.01) |

| f = 0.05 | 0.15 (−0.02) | 0.51 (0.03) | 0.07 (0.00) | 0.21 (0.02) | 0.04 (0.01) | 0.11 (−0.01) | |

| γ1,3 = 0 | 0.11 (0.14) | 0.19 (−0.05) | 0.06 (0.16) | 0.08 (−0.05) | 0.05 (0.18) | 0.04 (−0.04) | |

| 0.10 (−0.04) | 0.19 (−0.05) | 0.04 (−0.01) | 0.08 (−0.05) | 0.02 (0.00) | 0.04 (−0.04) | ||

| 0.13 (0.02) | 0.40 (0.01) | 0.06 (0.03) | 0.17 (0.01) | 0.04 (0.04) | 0.09 (−0.02) | ||

| 0.12 (0.03) | 0.35 (0.00) | 0.06 (0.04) | 0.14 (−0.01) | 0.04 (0.05) | 0.07 (−0.03) | ||

| 0.12 (0.03) | 0.34 (−0.03) | 0.06 (0.04) | 0.16 (−0.02) | 0.04 (0.03) | 0.09 (−0.03) | ||

| |

|

0.14 (0.00) |

0.40 (−0.01) |

0.06 (0.01) |

0.18 (0.00) |

0.04 (0.01) |

0.10 (−0.02) |

| f = 0 | 0.19 (−0.02) | 0.85 (0.03) | 0.09 (0.01) | 0.52 (0.01) | 0.06 (0.00) | 0.25 (0.01) | |

| γ1,3=−0.4 | 0.10 (0.01) | 0.89 (−0.72) | 0.05 (0.04) | 0.73 (−0.72) | 0.03 (0.05) | 0.65 (−0.73) | |

| 0.10 (0.02) | 0.87 (−0.71) | 0.05 (0.04) | 0.72 (−0.72) | 0.04 (0.06) | 0.65 (−0.73) | ||

| 0.15 (−0.02) | 0.74 (−0.15) | 0.08 (0.00) | 0.50 (−0.12) | 0.05 (0.00) | 0.26 (−0.08) | ||

| 0.14 (−0.02) | 0.71 (−0.25) | 0.07 (0.00) | 0.48 (−0.20) | 0.05 (0.01) | 0.26 (−0.15) | ||

| 0.14 (0.01) | 0.76 (−0.34) | 0.07 (0.02) | 0.51 (−0.19) | 0.05 (0.02) | 0.26 (−0.10) | ||

| |

|

0.16 (0.01) |

0.71 (−0.25) |

0.08 (0.01) |

0.47 (−0.12) |

0.06 (0.01) |

0.24 (−0.04) |

| f = 0.05 | 0.17 (0.01) | 0.74 (0.00) | 0.08 (−0.04) | 0.45 (0.09) | 0.05 (0.00) | 0.26 (0.02) | |

| γ1, 3=−0.4 | 0.16 (0.23) | 0.84 (−0.72) | 0.11 (0.25) | 0.69 (−0.73) | 0.10 (0.27) | 0.64 (−0.74) | |

| 0.12 (0.02) | 0.87 (−0.73) | 0.05 (0.04) | 0.70 (−0.73) | 0.04 (0.07) | 0.64 (−0.74) | ||

| 0.15 (0.05) | 0.65 (−0.17) | 0.07 (0.00) | 0.43 (−0.03) | 0.05 (0.04) | 0.27 (−0.07) | ||

| 0.15 (0.06) | 0.62 (−0.26) | 0.08 (0.02) | 0.41 (−0.11) | 0.05 (0.08) | 0.27 (−0.13) | ||

| 0.15 (0.09) | 0.67 (−0.36) | 0.08 (0.02) | 0.43 (−0.11) | 0.05 (0.04) | 0.27 (−0.09) | ||

| 0.16 (0.05) | 0.61 (−0.25) | 0.08 (−0.01) | 0.41 (−0.02) | 0.05 (0.01) | 0.25 (−0.03) | ||

NOTE: : model-based estimator; : model-free estimator; : estimator accounting for Hardy-Weinberg disequilibrium; and : multivariate and component-wise empirical-Bayes estimators; and : L1 and L2 penalized estimators. Here f is the fixation index quantifying departures from HWE, and γ1, 3 quantifies departures from gene-environment independence. HWE is f = 0, and G-E independence is γ1, 3 = 0. Monte Carlo standard errors of MSEs (biases) in the table range from 0.002−0.033 (0.006−0.027).

Now we consider the asymptotic theory for the EB-type estimator (7) when HWE and (G-E) independence hold, which implies βmodel = βfree (i.e., the model-based estimator is consistent). Let Ψmodel(D, G, X, Ωmodel) and Ψfree (D, G, X, Ωfree) be the individual score/estimating functions for the model-based and model-free estimators. These are the derivatives of the logarithms of (5) and (6), respectively, with respect to the parameters, with the exception that in the model-free case, the score for θ is as described in Section 2.3.1.

Let be minus the expectation of and let be defined analogously. Let ⇒ mean convergence in distribution to a random variable having the same distribution as the right hand side. It is a consequence of Theorems 2 and 3 in the Appendix B that , where

with Ip the identity matrix of size p = dim(β), and 0 the matrix of zeros of size p × q, q = dim(θ). Define and define . Then, it follows immediately that when HWE and (G-E) independence hold,

| ( 8 ) |

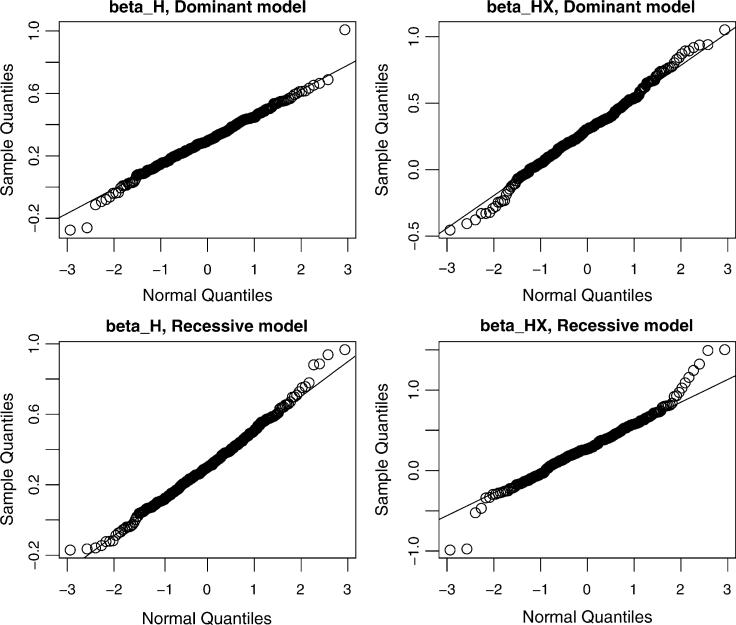

Of course, the limit distribution in (8) is not normally distributed, a phenomenon that is expected for many model-average estimators at the null or reduced model (Hjort and Claeskens 2003; Claeskens and Carroll 2007). However, simulation studies show that the lack of normality, while real, is not serious in practice in our context. The quantile-quantile plots shown in Figure 1 for comparing the distribution of the EB-type estimates from a set of simulations with the normal distribution illustrate this fact (see Section 5 for details about simulations). Moreover, the EB estimator in this situation can be more efficient than the model-free estimator not only in finite samples, but also in large samples (Tables 2 and 3, the blocks with f = 0, γ1,3 = 0). Such a phenomenon of “super-efficiency”, first observed by Hodges (e.g., see Lehmann 1983, pp. 405−406), is expected for many shrinkage estimators. Finally, we note that variance estimators we propose in the case of βmodel ≠ βfree provide remarkably good approximations for the variance of the EB estimators even when βmodel = βfree, although in the latter case the derivation of the asymptotic variances based on the δ-method is not strictly accurate, but it is acceptable in practice.

Figure 1.

Quantile-Quantile (Q-Q) plots for comparing the distribution of empirical Bayes estimates with the normal distribution. The empirical Bayes estimates for βH and βHX are obtained from the simulation study under HWE and G-E independence, with sample size N1 = N0 = 600 (1,000) in the dominant (recessive) genetic model.

4. PENALIZED LIKELIHOODS

A further consideration of (7) suggests an entirely different approach to combining assumption-laden and assumption-free methods in semiparametric problems with infinite dimensional nuisance parameters. Specifically, setting K* = I – K, we can rewrite (7) as

| ( 9 ) |

Because K* = 0 leads to the model-based estimator and K* = I leads to the model-free estimator, one interpretation of (9) is that one is shrinking the difference between the model-free and model-based estimators toward zero. With K* = 0 being interpreted as full shrinkage, a more useful interpretation of (9) is that one is shrinking the model-free estimator toward the model-based estimator when it is appropriate to do so.

With this idea in mind, we now turn to penalized likelihoods, which are also used for constructing shrinkage estimators. However, most of these proposals shrink parameters to zero. Based on the intuition of the EB-type estimators described in the previous paragraph, we instead propose shrinking the model-free estimator toward the model-based estimator (or equivalently, shrinking their difference to zero) by maximization of a penalized log-likelihood of the form

| ( 10 ) |

where denotes the estimate of βj from the model-based likelihood Lmodel, P(·) denotes a suitable penalty function and the λ-values denote parameter-specific penalties that determine the degree of shrinkage.

There are two unique features of (10). First, we propose shrinkage directly with respect to the focus parameters of interest. Given that we are trying to exploit G-E independence and HWE, which are assumptions about nuisance parameters, it may seem more natural that one maximizes a penalized likelihood where the penalties are given to the nuisance parameters. However, in a semiparametric model involving infinite dimensional nuisance parameters, this could become a challenging task. By formulating the problem with respect to the focus parameters themselves, however, we can simply work with the profile likelihoods that are completely free of the nuisance parameters. A second interesting feature of our proposal is that we are shrinking parameters, not toward some fixed values as is usually done, but toward the estimates obtained from an alternative model.

One can use both L1 (LASSO) and L2 (ridge) penalty functions, with the former given by and the latter by . For logistic regression models, L2 penalized likelihoods can be maximized by iteratively reweighted ridge regressions and hence can be implemented conveniently. An interesting feature of the L1 penalty is that it can produce “sparse” solutions [i.e., we can have certain estimates exactly equal to those obtained from the HWE and G-E independence model (Tibshirani 1996)]. More detailed discussion of the respective properties for the two types of penalty functions can be found in Hastie, Tibshirani, and Friedman (2001).

Two issues are important for practical implementation of the penalized likelihood estimation: (a) computation and (b) the choice of the penalty parameters λj. In the Appendix D we deal with issue (a) and in what follows we deal with issue (b).

4.1 Choice of the Penalty Parameters

Both L1 and L2 penalized estimation can be interpreted as Bayesian posterior mode estimation (Tibshirani 1996), with the prior given by the Laplace and the normal distributions, respectively. Note that the penalty parameter λj in the penalized log-likelihood (10) has a 1−1 correspondence to the variance τj of the prior distribution for ψj = βmodel,j – βfree,j; the L1 penalty corresponds a Laplace prior with variance , whereas the L2 penalty corresponds to a normal prior with variance 1/(2λj). As in Section 3, we use as a conservative estimate of τj. These facts in turn suggest that the choice of λj should be inversely proportional to and for the L1 and L2 penalized regression, respectively. Moreover, we would like to have the penalty parameters converge to zero in large samples, so that the resulting penalized estimators are asymptotically equivalent to the model-free estimator and hence are consistent, even when βmodel ≠ βfree (i.e., HWE/H-X independence does not hold). Accordingly, we thus propose the following choices of the penalty parameters. For L2-penalized regression we suggest using , where νj is the variance of ; for L1-penalized regression, we suggest . It is readily seen that these choices of penalty parameters satisfy both the desired properties: they yield more shrinkage toward the model-based estimator when the magnitude of the estimated bias is smaller, and will converge to zero in large samples when ψ = βmodel – βfree ≠ 0 because νj → 0 as N → ∞.

5. SIMULATIONS

5.1 Set Up

We conducted simulation studies to examine the performance of the EB-type and penalized likelihood shrinkage estimators. We implemented two EB estimators, termed EB1 and EB2, one corresponding to “multivariate shrinkage” with , where V is the estimated variance-covariance of , and the other corresponding to “componentwise shrinkage” with , where is the ith component of and νi is the ith diagonal component of V. We also implemented two penalized likelihood methods, PL1 and PL2, corresponding respectively to the L1 and L2 penalties, with the penalty parameters chosen as described in Section 4.1. Haplotype data were simulated using the haplotype patterns and frequencies (see Table 1) for five Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) along a diabetes susceptibility region on chromosome 22, reported in the Finland-United States Investigation of Non-Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus (FUSION) study (Epstein and Satten 2003). The environmental covariate X is a binary variable, with pr(X = 1) = 0.3.

Table 1.

Haplotype frequencies used in the simulation

| j | Haplotype | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10011 | 0.3327 |

| 2 | 01011 | 0.1409 |

| 3 | 01100 | 0.2489 |

| 4 | 10000 | 0.0295 |

| 5 | 10100 | 0.0611 |

| 6 | 10110 | 0.0453 |

| 7 | 11011 | 0.1416 |

In our simulations, given the environmental covariate X, we generated a 5-SNP diplotype for a subject according to the model

| ( 11 ) |

where j1, j2 = 1, . . ., 7 index haplotypes, and the diplotype (h1, h1) is chosen as the reference. The parameters {γ0j1j2} are specified so that the marginal (unconditional on X) diplotype frequencies are given as

| ( 12 ) |

where the θj are the haplotype frequencies given in Table 1, and f is the fixation index quantifying the departure from HWE, with f = 0 indexing HWE (Satten and Epstein 2004). The parameters {γ1,j} are all zero for j ≠ 3, and γ1,3 is set to 0 or −0.4, which quantifies the departure from haplotype-environment independence, with γ1,3 = 0 indexing independence. Hence, f = 0 and γ1,3 = 0 corresponds to an “ideal” model where both HWE and H-X independence hold. Given X and H, disease status is generated from the model

| ( 13 ) |

where is coded as indicating whether a subject carries at least one copy of the causal haplotype “01100” (j = 3) (i.e., a dominant genetic model), or indicating whether a subject carries two copies of this haplotype (i.e., a recessive model). The parameter values (β0, βH, βX, βHX) = (−3.0, 0.3, 0.3, 0.3). A case-control sample with N1 cases and N0 controls was sampled from the simulated population. Once we generated the data in the previous fashion, we deleted the phase information.

In the simulations we compare the shrinkage estimators with the model-free and model-based estimators. We also consider the estimator accounting for the Hardy-Weinberg disequilibrium of the form (12) but not accounting for H-X dependence, which is proposed in Lin and Zeng (2006).

5.2 Efficiency and Bias

Tables 2 and 3 display simulation results for the dominant and recessive models, respectively. We take the sample sizes to be N1 = N2 = 150, 300, or 600 for the dominant model and N1 = N0 = 300, 600 or 1,000 for the recessive model. To save space, we report only the results for βH and βHX for the causal haplotype “01100” (j = 3), although during the analysis we fitted a “full” model containing all haplotypes and their interactions with the environmental covariate. We make the following key observations.

When the assumptions of HWE and H-X independence are met (f = 0, γ1,3 = 0), all the different estimators are essentially unbiased. In this situation, the model-based estimator can be remarkably more efficient than the model-free estimator, especially when the genetic effect is recessive. The different shrinkage estimators give up some efficiency relative to the model-based estimator, but all of them, with the occasional exception of EB1 (multivariate empirical-Bayes shrinkage), achieve major gains in efficiency over the model-free estimators in small samples (N1 = N0 = 150 or 300). Moreover, EB2 (component-wise empirical-Bayes shrinkage) consistently retains substantial gains over the model-free estimator even for larger sample sizes such as N1 = N0 = 600 or N1 = N0 = 1,000. The estimator assuming Hardy-Weinberg disequilibrium performs similarly to the model-based estimator.

When the assumptions of HWE or H-X independence or both are violated, the model-based estimator yields very large bias for the genetic main effect or the gene-environment interaction parameter or both. The model-free estimator, although it depends weakly on these same assumptions, has negligible bias. As a result, in these situations, the mean squared error (MSE) for the model-based estimator is often much larger than that of the model-free estimator when the violation of model assumptions is severe or the sample size is large. Note that when only the assumption of HWE is violated but H-X independence still holds (f = 0.05, γ1,3 = 0), the estimator performs best among all the estimators considered, which is as expected because assumes exactly the true model in this setting. When the H-X independence is violated, performs similarly to the model-based estimator and has large bias and MSE. All of the shrinkage estimators adapt to the situation quite nicely and reduce the bias dramatically. The MSE of the shrinkage estimators usually remains much smaller than that of the model-free estimator when the sample size is small, whereas the performances of the shrinkage and model-free estimators become quite similar in large samples. Overall, among the various shrinkage estimators, the PL1 produces the smallest MSE in most cases under the dominant model, whereas the EB2 and PL2 produce the smallest MSE in most cases under the recessive model. The magnitude of the bias for all shrinkage estimators is similar, with that for the EB2 and PL1 estimators being the largest in most cases.

5.3 Variance Estimators

Variance estimators for the EB and penalized estimators are given in the Appendices C and F. In Tables given in the supplementary material and available from the first author, we have studied the performance of these variance estimators. We observed for each shrinkage estimator that the mean of the estimated variances over simulations was quite close to the empirical variance of the shrinkage estimator. The variance estimators work remarkably well even when HWE and (G-E) independence assumptions are met, although in this situation the application of the δ-method is indeed not technically correct due to nonnormality of the limiting distribution.

6. CASE-CONTROL STUDIES OF COLORECTAL ADENOMA AND PROSTATE CANCER

In this section, we discuss results from two case-control data examples. The examples were chosen in such a way that from a priori biological grounds one would expect the gene-environment independence assumption to hold in one example, but probably not in the other. The two examples taken together illustrate how the different shrinkage estimators adapt to alternative scenarios for the gene-environment distribution.

6.1 Background of the Examples

The first application involves a case-control study of colorectal adenoma, a precursor of colorectal cancer. The study sample includes 628 prevalent advanced adenoma cases and 635 gender-matched controls, selected from the screening arm of the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial at the National Cancer Institute, USA (Gohagan, Prorok, Hayes, and Kramer 2000; Moslehi et al. 2006). One of the main objectives of this study is to assess whether the smoking-related risk of colorectal adenoma may be modified by certain haplotypes in NAT2, a gene known to be important in the metabolism of smoking related carcinogens. In addition, because NAT2 is involved in the smoking metabolism pathway, potentially it can influence an individual's addiction to smoking itself, causing the gene-environment independence assumption to be violated.

The second application involves a case-control study of prostate cancer. The sample includes 749 prostate cancer cases and 781 controls, also selected from the screening arm of the PLCO trial described earlier. The main objective of the study is to examine the relationship between risk of prostate cancer and [25(OH)D], a serum level biomarker of vitamin D, that reflects both dietary and sunlight exposures. The anticancer effect of vitamin D is hypothesized due to the ability of prostate cells to convert [25(OH)D)] into 1,25-dihydroxy-vitamin D [1,25(OH)2D], the most active form of this vitamin, which regulates the gene transcription of many proteins involving cellular differentiation, proliferation, and apoptosis via the vitamin D receptor (VDR). It is thus of interest to see whether genetic polymorphisms in the VDR gene modify the relationship between [25(OH)D)] and risk of prostate cancer. Given the “downstream” role of the VDR gene in the vitamin-D pathway, it is very unlikely that these polymorphisms actually could influence the level of the [25(OH)D] itself. Thus, the gene-environment independence assumption in this application is likely to be valid.

In the colorectal adenoma study, genotype data were available on six SNPs, for which seven common haplotypes (with estimated frequency > 0.5%) are inferred by the EM algorithm of Li, Khalid, Carlson, and Zhao (2003). In the prostate cancer study, genotype data were available on three SNPs, for which four common haplotypes (with estimated frequency > 0.5%) are inferred by the expectation maximization (EM) algorithm. Our association analysis is performed by fitting the logistic regression model (13). The haplotype covariate vector is coded by a multiplicative rule (i.e., the hth component of is the number of haplotypes h carried by a subject). The most frequent haplotype is chosen as the reference haplotype, and those with haplotype frequency < 2% are grouped into the reference.

For the colorectal adenoma study, the environmental covariate vector X includes the variables Age (age in years), Female (indicator for female gender), Smk1 and Smk2 (indicators respectively for former and current smokers). All the environmental variables are centered to have mean zero. The haplotype-environment interaction terms include the interactions of the haplotype “101010”, a key haplotype of interest because of its known role in the metabolism of smoking related carcinogens (Chang-Claude et al. 2002), with Smk1 and Smk2. For the prostate cancer study, the environmental covariate vector X includes the age level (categorized into four groups), center (nine groups), and the [25(OH)D)] level (nmol/L). We consider the interaction of the haplotypes “000” and “001” with the standardized [25(OH)D)] level (standardized by its sample standard deviation), which are the most promising interactions according to preliminary analysis.

6.2 Results

Table 4 shows the results for the two applications, based on the association analyses introduced in Sections 2, 3, and 4. For simplicity, we report only results for the interaction parameters of main interest (the full models we fitted to the two datasets are described in Section 6.1). Also, we report only results from the model-free and model-based analyses, the component-wise empirical Bayes shrinkage analysis, and the L1 penalized likelihood analysis (with the penalty parameters chosen by matching them with the estimated prior variances, as discussed in Section 4.1). The results from the multivariate empirical Bayes shrinkage analysis are quite similar to those from the component-wise empirical Bayes shrinkage analysis, and a similar relationship holds between the L1 and the L2 penalized likelihood analyses. The standard errors are obtained by the formulas given in the Appendices C and F, and the p-values are obtained by normal approximation.

Table 4.

Results for haplotype-environment interaction analyses of the colorectal adenoma study (Example 1) and the prostate cancer study (Example 2). The full models fitted are described in Section 6.1

| Example 1 |

Example 2 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method | Interaction | SE | p value | Interaction | SE | p-value | ||

| Model-free | 101010*Smk1 | 0.149 | 0.217 | 0.494 | 000*VD | −0.206 | 0.123 | 0.093 |

| 101010*Smk2 | −0.558 | 0.279 | 0.045 | 001*VD | 0.127 | 0.085 | 0.135 | |

| Model-based | 101010*Smk1 | 0.076 | 0.153 | 0.618 | 000*VD | −0.188 | 0.080 | 0.019 |

| 101010*Smk2 | −0.291 | 0.181 | 0.108 | 001*VD | 0.046 | 0.061 | 0.453 | |

| EB | 101010*Smk1 | 0.090 | 0.173 | 0.602 | 000*VD | −0.189 | 0.082 | 0.021 |

| 101010*Smk2 | −0.461 | 0.295 | 0.118 | 001*VD | 0.095 | 0.089 | 0.285 | |

| PL | 101010*Smk1 | 0.125 | 0.182 | 0.490 | 000*VD | −0.188 | 0.080 | 0.019 |

| 101010*Smk2 | −0.492 | 0.249 | 0.048 | 001*VD | 0.121 | 0.082 | 0.143 | |

NOTE: model-free: assuming HWE and haplotype-environment independence conditional on genotype; model-based: assuming unconditional HWE and haplotype-environment independence; EB: the component-wise empirical Bayes method; PL: the penalized likelihood method based on Lasso; Smk1: former smoker; Smk2: current smoker; VD: [25(OH)D)] level.

The major conclusions we draw from Table 4 are as follows. For the colorectal adenoma study, where we expect that the haplotype-environment independence may be violated and hence the model-based analysis may be biased, we do observe a large discrepancy between the point estimates from the model-free and the model-based analyses. The empirical Bayes and the penalized likelihood methods we propose nicely adapt to the situation and produce results much closer to the model-free analysis than the model-based analysis. In summary, carriers of the haplotype “101010” tend to have lower smoking related risk than noncarriers. This agrees with previous laboratory and epidemiologic studies that have identified the haplotype “101010”, known as NAT2*4, as a rapid metabolizer for smoking related carcinogens (e.g., see Moslehi et al. 2006).

For the prostate cancer study, where we expect haplotype-environment independence to hold, the model-free and the model-based analyses do produce very similar point estimates, revealing that both of them may be unbiased. However, the model-based analysis is more efficient than the model-free analysis. We note that in this example the component-wise empirical Bayes analysis and the L1 penalized likelihood analysis produce results quite close to the model-based analysis, especially in the interaction of the [25(OH)D)] level with haplotype “000”, and thus retain the efficiency gain. In summary, we can conclude from the model-based and the proposed shrinkage methods that the haplotype “000” may significantly modify the risk of prostate cancer associated with the [25(OH)D)] level.

7. DISCUSSION

In this work we first examined retrospective likelihood methods for haplotype-based case-control studies. A “model-free” retrospective likelihood was proposed, which, in contrast to the “model-based” retrospective likelihood (Spinka et al. 2005) that assumes HWE and haplotype-environment independence to specify the joint distribution of diplotypes and environmental exposures, utilizes the same assumptions only to specify the conditional diplotype distribution given environmental exposures and unphased genotypes. Our simulation studies show that such retrospective likelihood analysis leads to inference that is very robust to violation of the HWE and (G-E) independence assumptions. With the rare disease assumption, the proposed “model-free” retrospective likelihood is closely related to the “prospective likelihood” used by Zhao et al. (2003) and Lake et al. (2003).

We further considered a number of alternative shrinkage estimation techniques for adaptive relaxation of the HWE and G-E independence assumptions from the model-based retrospective likelihood. These different shrinkage estimators were constructed by different ways of shrinking the model-free estimator toward the model-based estimator, with the aim of achieving better finite sample properties in terms of the bias-efficiency trade-off. Our simulation studies reveal that the proposed shrinkage estimators can dramatically reduce the bias of “model-based” retrospective methods in the presence of violation of model assumptions. On the other hand, when the model assumptions are satisfied, exactly or approximately, the shrinkage estimators can retain a considerable gain in efficiency over the “model-free” estimators. Thus, overall, the proposed techniques provide a natural way of trading off between bias and efficiency in the type of problems we studied in this article. Two empirical illustrations were described; one where the assumption of G-E independence is likely violated and one where it likely holds, and analysis results from these examples are consistent with those from the simulations.

We also have studied asymptotic theory for the EB and penalized shrinkage estimators. We have shown that the proposed EB estimator is approximately whether the underlying assumptions of HWE and G-E independence hold or not. Further, when the assumptions of HWE or G-E independence assumptions or both are violated, we have shown that the EB estimator has an asymptotic normal distribution, the variance of which can be reliably estimated in a simple closed form using the δ method. On the other hand, when the assumptions of HWE and G-E independence are met, the proposed EB estimator can be viewed as a model-average estimator that converges to a nonnormal distribution. In practice, however, we found that this limiting nonnormal distribution can be well approximated by a normal distribution, the variance of which can still be reliably estimated using the same estimator derived for the case when the model assumptions fail. All the previously mentioned properties are also satisfied by the penalized estimators for suitable choice of the penalty parameters.

In this article, we have compared the performance of the alternative shrinkage estimators in terms of mean squared errors of the estimators. In large genetic association studies, however, one is often first interested in testing as opposed to estimation. It is important to note that the misspecification of HWE or (G-E) independence or both causes bias even under the null hypothesis of no association or no interaction. Thus, from both the testing and estimation points of view, it is important to account for the impact of model misspecification. Although in this article we do not study the properties of shrinkage estimators from a testing point of view, a recent study has reported that EB-type shrinkage estimators indeed performs very well for large scale association testing (Mukherjee et al. 2008).

The advantages in bias, efficiency, computational simplicity, and availability of a unified approach to inference make the proposed shrinkage procedures very appealing in genetic association studies. Further, using modern shrinkage and penalization techniques to combine assumption-laden and assumption-free methods in semiparametric problems is an idea that transcends genetic association studies. We hope that this work will lead to further research in this general area.

Acknowledgments

Chen's research was supported by the National Science Council of ROC (NSC 95−2118-M-001−022-MY3). Chatterjee's research was supported by a gene-environment initiative grant from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (RO1HL091172−01) and by the Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute. Carroll's research was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute (CA57030, CA104620) and by Award Number KUS-CI-016−04, made by King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST). The authors thank the editor, associate editor, and referees for their helpful comments.

APPENDIX A: LINKING THE CASE-CONTROL AND ALTERNATIVE SAMPLING SCHEMES

In this section, we use the subscripts “alt” and “cc” to denote the expectation operators under the alternative (see Section 2.3.3) and the case-control sampling schemes. We drop the subscript “free” for the parameters.

Let Ψfree(D, G, X, Ω) be the estimating function we consider for the “model-free” estimation, where the estimating function for β is obtained by the score ∂ log Lfree(D, G, X, Ω)/∂β, and the estimating function for θ is obtained by the EM-type estimating function based on the controls (D = 0) (Zhao et al. 2003). Because Lfree is a legitimate likelihood function in the alternative sampling scheme and the rare disease assumption is used, Ψfree(D, G, X, Ω) is an unbiased estimating function for Ω in the alternative sampling scheme. If• = (D, G, X), then this means that 0 = Ealt{Ψfree(•, Ω)|R = 1} at the true value of Ω.

The following result will be used to justify using Ψfree(D, G, X, Ω) as an unbiased estimating function in the case-control sampling scheme.

Theorem 1. For any function K(D, G, X),

| (A.1) |

A.1 PROOF OF THEOREM 1

By definition,

Further, note that pralt(D = d|R = 1) pd. Recall that the distribution of R depends only on D. It then follows that

completing the proof. In the previous argument, the second line uses the fact that the distribution of R is independent of (H, G, X) given D, whereas the third line notes that probability calculations about the distribution of (H, G, X) given D are the same in either sampling scheme.

APPENDIX B: ASYMPTOTIC THEORY FOR (5) AND (6)

Theorem 1 in Appendix A shows that expectations in the case-control sampling scheme are the same as expectations in the alternative sampling scheme, and hence that Ψfree(·) is an unbiased estimating function [i.e., ]. Let Ifree be the information matrix,

which can be estimated as

Define where the expectations are estimated as . Also define , which can be estimaed by

Then because of Theorem 1, we have the following result.

Theorem 2. As N0, N1 → ∞,

| (A.2) |

In particular this means that . In addition, the estimates , and are consistent for and Λfree.

For the sake of completeness, we note that a similar expansion was derived by Spinka, et al. (2005) when HWE and (G-E) independence hold.

Theorem 3. As N0, N1 → ∞,

| (A.3) |

In particular, this means that . In addition, the estimates and are consistent for Imodel and Λmodel (all the matrices here are defined analogously to their counterparts defined in Theorem 2).

APPENDIX C: ASYMPTOTIC THEORY AND VARIANCE ESTIMATION FOR EB SHRINKAGE ESTIMATORS WHEN βmodel ≠ βfree

Here we focus on ; the asymptotic theory for can be derived analogously (the definitions for the EB1 and EB2 empirical Bayes-type estimators is given in Section 5.1). The asymptotic theory is simple, because when βmodel ≠ βfree, the EB shrinkage estimators are asymptotically equivalent to the model-free estimator (see later). Our main goal here is to develop for the EB shrinkage estimator an approximate covariance matrix estimator that is more accurate in finite samples than the covariance matrix for the model-free estimator. Note that, although the latter also serves as an estimator for variance of the EB estimator due to the asymptotic equivalence, it is often too conservative in finite samples (simulation data not shown).

Let , and denote the estimated variance-covariance of . Let , and be defined analogously. The block-diagonal terms of are obtained directly from Theorems 2 and 3, and, by Theorems 2 and 3, the off block-diagonal terms are given by

and its transpose, where Ip is the identity matrix of size p = dim(β), 0 is a p × q zero matrix (q = dim(θ)), and the matrix , with . Let β* = (βmodel, βfree), ψ and βEB1 be the asymptotic limits of and , respectively. Note that when βmodel ≠ βfree, it is easy to see that in probability when N goes to ∞ because in this case V → 0 and . Thus, βEB1 = βfree.

To get an approximate estimated covariance matrix, which is more accurate than that of the model-free estimator in small samples, we use the following calculations. Define

and note that by a first order Taylor expansion, we can write

where the p × 2p matrix G1 is given as

Of course, because V = Op(N−1), it follows that . Thus, is approximately and asymptotically normal. Moreover, the asymptotic variance of can be estimated as , where is the plug-in estimate of G1. The analogous asymptotic variance-covariance matrix estimator for is given by , where is the plug-in estimate for

APPENDIX D: COMPUTATION FOR PENALIZED LIKELIHOOD ESTIMATION

The penalized likelihood estimators and are obtained from (10) with L1 (LASSO) and L2 (ridge) penalties, respectively. Their implementation involves solving the corresponding score functions for (10); note that the score function used for θ in Lfree(·) is modified as described in Section 2.3.1.

Following Fan and Li (2001, Section 3.3), we use a unified Newton-Raphson algorithm for implementing these estimators, where the penalty function is approximated locally by a quadratic function, which is exact for the L2 penalty. Specifically, write the penalty function P(βj, βmodel,j) as P(|bj|) with bj = βj − βmodel,j, and take , where is a current estimate for βj. Approximate P(|bj|) by a quadratic function around such that

where the superscript dot denotes derivative. Let

where Ψfree(·) is defined in Section 3.1, and

Let be the “model-based” estimates for Ω obtained from (6). Then at a current parameter estimate Ω* = (β*, θ*), the score function for the penalized likelihood can be approximated by

where the matrix Γ(Ω*) is diagonal whose diagonal elements are for those corresponding to βj, and are 0 for those corresponding to θ, becaue we do not penalize the estimates for haplotype frequency parameters θ. The updated parameter estimate is then

In the case where the L1 penalty is used, when becomes close to (e.g., the absolute difference < 10−5), we set and set the corresponding diagonal element of Γ(Ω) to a large value (e.g., 105). We have found that this algorithm is very stable and fast. A sandwich-type variance estimator is proposed in Appendix F for the resulting penalized estimator.

APPENDIX E: ASYMPTOTIC THEORY FOR PENALIZED ESTIMATORS

We first consider the case that βmodel ≠ βfree. In this case, if λj → 0 as N → ∞ for βmodel,j ≠ βfree,j, it is then obvious that the penalized estimator for such choices of penalty parameters is asymptotically equivalent to the model-free estimator. Note that the choices of λjs presented in Section 4.1 satisfies this condition because νj = Op(N−1), whereas .

Next, as in Section 3.1, we consider the case where HWE and G-E independence hold, so that βmodel = βfree and θmodel = θfree, and hence Ωmodel = Ωfree. In this case, we will show that the penalized estimator, though it has the same limit value as the model-free estimator, is a different estimator from the model-free estimator. In fact, from the asymptotic distribution for the penalized estimator derived later, it is seen that the penalized estimator is a model-average estimator, and hence is more efficient than the model-free estimator.

Consider the L2-penalized estimator first. With a slightly expanded notation we have

say, where Ψfree,i(Ωfree) = Ψfree(Di, Gi, Xi, Ωfree) and similarly for Ψmodel,i(Ωmodel).

Define . Then the L2-penalized estimator as described in Section 4.1, , solves

By Taylor series, we see that

Dropping the dependence of Ifree on Ωfree, remembering that the leading term in the previous expression has the limit distribution and then solving, we see that

Note that this limit distribution, just as that for the EB estimators given in (8), is a type of distribution for a model-average estimator. It is then seen that, when HWE and G-E independence hold, the limit distribution for is in principle not a normal distribution. Our simulations, however, show that the departure from normality in this case is b not large.

Now consider the asymptotic distribution for the L1-penalized estimator, , when HWE and G-E independence hold, with the penalty parameter λ being chosen as in Section 4.1. Let , where . By Taylor expansion we have

which implies that

which is again a form of the distribution for a model-average estimator, and hence is in general not normally distributed.

APPENDIX F: VARIANCE ESTIMATION FOR PENALIZED ESTIMATORS

The major purpose of this section is to derive accurate and easily computed approximate variance estimates for the penalized estimators, using sandwich ideas. Here we assume that βmodel ≠ βfree, and the penalty parameters λjs are chosen so that λj → 0 as N → ∞. As discussed in Appendix E, the penalized estimator in this case is asymptotically normal with mean ΩPL = Ωfree.

Let

and , where Ψmodel,i(Ωmodel) and Ψfree,i(Ωfree) are defined as in the Appendix E. In Appendix D we approximated the score function by

| (A.4) |

where the matrix Γ(Ω) is diagonal with diagonal elements , for those corresponding to βj, and 0 for those corresponding to θ.

Recall that in our proposal the penalty parameters λ may be functions of . Let

Accordingly, we can further write ΨPL = Σi ΨPL,i(Ω) +Op(N1/2), where

where the matrix P(Ω, Ωmodel, Ωfree) is diagonal with diagonal elements , for elements corresponding to βj, and 0 for elements corresponding to θ. It is thus seen that we have N−1/2ΨPL = N−1/2Ψfree (Ω) + Op(1) (i.e., the penalized estimator is asymptotically equivalent to the mode-free estimator when βmodel ≠ βfree, if the penalty parameters are chosen such that , and provided that the terms are bounded). The choices of λj in Section 4.1 satisfy theses conditions.

Denote by , and the penalized, model-based and model-free estimators, respectively, and , where . Then a sandwich-type variance estimator for the penalized likelihood estimator can be obtained as

where for a vector A.

REFERENCES

- Chang-Claude J, Kropp S, Jäger B, Bartsch H, Risch A. Differential Effect of NAT2 on the Association between Active and Passive Smoke Exposure and Breast Cancer Risk. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2002;11:698–704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee N, Carroll RJ. Semiparametric Maximum Likelihood Estimation in Case-Control Studies of Gene-Environment Interactions. Biometrika. 2005;92:399–418. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee N, Chen Y-H. Maximum Likelihood Inference on a Mixed Conditionally and Marginally Specified Regression Model for Genetic Epidemiologic Studies with Two-Phase Sampling. (Series B).Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 2007;69:123–142. [Google Scholar]

- Claeskens G, Carroll RJ. Post-Model Selection Inference in Semiparametric Models. Biometrika. 2007;94:249–265. [Google Scholar]

- Clark AG. The Role of Haplotypes in Candidate Gene Studies. Genetic Epidemiology. 2004;27:321–333. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein MP, Satten GA. Inference on Haplotype Effects in Case-Control Studies Using Unphased Genotype Data. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2003;73:1316–1329. doi: 10.1086/380204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan J, Li R. Variable Selection via Nonconcave Penalized Likelihood and Its Oracle Properties. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2001;96:1348–1360. [Google Scholar]

- Gohagan JK, Prorok PC, Hayes RB, Kramer BS. The Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial of the National Cancer Institute: History, Organization, and Status. Controlled Clinical Trials. 2000;21(Suppl):251S–272S. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(00)00097-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastie T, Tibshirani R, Friedman J. The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction. Springer-Verlag; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hjort NL, Claeskens G. Frequentist Model Average Estimators. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2003;98:879–899. (with discussion) [Google Scholar]

- Lake SL, Lyon H, Tantisira K, Silverman EK, Weiss ST, Laird NM, Schaid DJ. Estimation and Tests of Haplotype-Environment Interaction When Linkage Phase Is Ambiguous. Human Heredity. 2003;55:56–65. doi: 10.1159/000071811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann EL. Theory of Point Estimation. John Wiley and Sons; New York: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Li SS, Khalid N, Carlson C, Zhao LP. Estimating Haplotype Frequencies and Standard Errors for Multiple Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms. Biostatistics (Oxford, England) 2003;4:513–522. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/4.4.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin DY, Zeng D. Likelihood-Based Inference on Haplotype Effects in Genetic Association Studies. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2006;101:89–118. (with discussion) [Google Scholar]

- Moslehi R, Chatterjee N, Church TR, Chen J, Yeager M, Weissfield J, Hein DW, Hayes RB. Cigarette Smoking, N-acetyltransferase Genes and the Risk of Advanced Colorectal Adenoma. Pharmacogenomics. 2006;7:819–829. doi: 10.2217/14622416.7.6.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee B, Ahn J, Gruber SB, Rennert G, Moreno V, Chatterjee N. Tests for Gene-Environment Interaction from Case-Control Data: A Novel Study of Type I Error, Power and Designs. Genetic Epidemiology. 2008 doi: 10.1002/gepi.20337. Epub PMID: 18473390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee B, Chatterjee N. Exploiting Gene-Environment Independence for Analysis of Case-Control Studies: A Shrinkage Approach to Trade Off Between Bias and Efficiency. Biometrics. 2008;64:685–694. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2007.00953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prentice RL, Pyke R. Logistic Disease Incidence Models and Case-Control Studies. Biometrika. 1979;66:403–411. [Google Scholar]

- Satten GA, Epstein MP. Comparison of Prospective and Retrospective Methods for Haplotype Inference in Case-Control Studies. Genetic Epidemiology. 2004;27:192–201. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaid DJ. Evaluating Associations of Haplotypes with Traits. Genetic Epidemiology. 2004;27:348–364. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaid DJ, Rowland CM, Tines DE, Jacobson RM, Poland GA. Score Tests for Association Between Traits and Haplotypes When Linkage Phase Is Ambiguous. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2002;70:425–434. doi: 10.1086/338688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinka C, Carroll RJ, Chatterjee N. Analysis of Case-Control Studies of Genetic and Environmental Factors With Missing Genetic Information and Haplotype-Phase Ambiguity. Genetic Epidemiology. 2005;29:108–127. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stram DO, Pearce CL, Bretsky P, Freedman M, Hirschhorn JN, Altshuler D, Kolonel LN, Henderson BE, Thomas DC. Modeling and E-M Estimation of Haplotype-Specific Relative Risks from Genotype Data for a Case-Control Study of Unrelated Individuals. Human Heredity. 2003;55:179–190. doi: 10.1159/000073202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tibshirani RJ. Regression Shrinkage and Selection via the LASSO. (Series B).Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 1996;58:267–288. [Google Scholar]

- Wallenstein S, Hodge SE, Weston A. Logistic Regression Model for Analyzing Extended Haplotype Data. Genetic Epidemiology. 1998;15:173–181. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2272(1998)15:2<173::AID-GEPI5>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao LP, Li SS, Khalid NA. Method for the Assessment of Disease Associations with Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Haplotypes and Environmental Variables in Case-Control Studies. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2003;72:1231–1250. doi: 10.1086/375140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]