Abstract

Background

The rupture of a cerebral aneurysm can result in a hemorrhagic stroke. A flow diverter, which is a porous tubular mesh, can be placed across the neck of a cerebral aneurysm to induce the cessation of flow and initiate the formation of an intraaneurysmal thrombus. By finding a correlation between Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV) and Digital Subtraction Angiography (DSA), a better assessment of how well an aneurysm is excluded from the parent artery can be made in the clinical setting.

Methods

A model of a rabbit elastase-induced aneurysm was connected to a mock circulation loop. The model was then placed under angiography. Recorded angiograms were analyzed so that a contrast concentration-time curve (CCTC) based upon the average grayscale intensity inside the aneurysm could be determined. That curve was then fit to a mathematical model that quantifies the influence of convection and diffusion on contrast transport. Optimized parameters were correlated to the intraneurysmal mean kinetic energy measured by PIV in the same aneurysm model.

Results

A strong correlation was observed between the convection and diffusion time constants and the mean kinetic energy inside the aneurysm.

Discussion

Analyzing the flow of angiographic contrast into and out of the aneurysm after implantation of a flow diverter allows for prediction of the efficacy of the device in excluding the aneurysm. Correlating hydrodynamic measures obtained by angiography to those obtained by detailed techniques such as PIV increase confidence in such predictions.

Keywords: Intracranial aneurysm, stent, mathematical modeling, convection, diffusion, time constant, kinetic energy, hemodynamics, flow diverter, PIV, DSA

BACKGROUND

Stroke is the third leading cause of death in the United States. About 5% of the strokes each year are from subarachnoid hemorrhage, which in most cases results from rupture of a brain aneurysm [1]. There are a myriad of factors involved in the rupture potential of an aneurysm. The size (greater than 10 mm) and shape (multi-lobular) of the aneurysm, location (basilar and posterior communicating artery), elevated blood pressure, current smoking, or excessive alcohol intake can trigger a rupture.

A flow diverter can be used to exclude an aneurysm from the circulation. It is based on the realization that an aneurysm is a disease of the parent vessel and by placing a porous scaffold across the aneurysm ostium, it is possible to divert the flow of blood away from the aneurysm and downstream into the parent vessel. The result is the formation of a thrombus inside the aneurysm, remodeling of the parent artery and the return of blood flow through the parent artery to normal physiological states [2, 3]. Experimental aneurysm models in animals are usually employed to investigate aneurysm occlusion devices. The elastase-induced aneurysm in rabbit is an example of such an in vivo model where the vasculature of the animal is manipulated to create an aneurysm. This model produces aneurysms of a similar size and structure to aneurysms found in humans [4–7]. To minimize use of animals, optically clear models are employed such that optimization and analysis of devices can be performed in bench top experiments. A transparent elastomer model based on the aneurysm of the rabbit model has been fabricated previously [6]. This vascular replica is advantageous because it can be reused for many devices in multiple experiments.

In this investigation the vascular replica of the rabbit elastase-induced aneurysm was used to study the influence of flow diverters on intraaneurysmal flow. The purpose was to find a correlation between the intraneurysmal flow activity as measured by Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV) and angiographic contrast concentration-time curves (CCTC) obtained by Digital Subtraction Angiography (DSA) [8, 9]. Such correlations should allow a better assessment of how well flow diverters are able to reduce the flow activity in the aneurysm using only angiographic techniques, which may eventually aid the endovascular physician in determining the occlusion potential of the aneurysm.

METHODS

Particle Image Velocimetry

Detailed PIV studies on the vascular replica of the rabbit elastase-induced aneurysm have previously been conducted [8]. The instantaneous kinetic energy inside the aneurysm was derived by summation of the squares of the magnitudes of all instantaneous velocity vectors within the aneurysm. The mean kinetic energy was then calculated as the temporal (cardiac cycle) average of the instantaneous kinetic energy. Intraneurysmal mean kinetic energies after implantation of six different flow diverters with three varying porosities (65%, 70% and 75%) and two different ranges of pore densities were calculated in the study [8].

Angiographic Quantification

Model

The compliant elastomer model was connected to a mock circulatory loop. A computer controlled piston pump (CompuFlow 1000, Shelly Medical Imaging Technology, Ontario, Canada) was used to simulate pulsatile flow through the anesthetized rabbit aorta [8]. For improved visibility, the elastomer model was scaled up by a factor of 1.36 and the Reynolds and the Womersley numbers in the model were matched to those in the rabbit as follows. The working fluid in the flow rig was a mixture of distilled water and glycerol (40:60 by volume), which was identical to the fluid used in the previous PIV experiment [8]. The flow waveform supplied to the pump was adjusted to a cardiac cycle of 506 milliseconds in duration. With these adjustments the fluid dynamic similarity parameters were computed to be the same as in the PIV experiment so that correlations between the two experiments could be determined with high fidelity.

Data Collection

Six identical flow diverters to the ones used in the PIV experiment were inserted, one at a time, into the parent artery of the model across the ostium of the aneurysm. The test section was placed in the angiographic field and when stable conditions were achieved, radio-opaque contrast (Omnipaque 300, GE Healthcare, United Kingdom) diluted with distilled water at a ratio of 1:1 by volume was injected simultaneously with image acquisition. The injections of the contrast was automated to achieve a repeatable injection rate of 2 cc/sec and for each experiment a total of 5 cc of contrast fluid were injected into the test section of the flow apparatus. Angiographic images were acquired for 20 seconds at a rate of 30 frames per second.

Data Processing

The images produced during high speed acquisition were concatenated by the angiography unit into single large files. The images in each file were then separated into a sequence of individual images. In the images, each pixel is assigned a grayscale intensity value where the lowest numerical value is considered black while the highest value is considered white. An image before start of contrast injection was taken as a mask and all subsequent images were logarithmically subtracted from the mask image so that the background information could be removed. For analysis purposes it was convenient to invert the intensity values and enhance the brighter pixels for better visualization of the contrast. Thereafter, a region of interest (ROI) was selected around the lumen of the aneurysm and the average grayscale intensity (AGI) of all the pixels within the ROI was calculated. The CCTC was then generated by sequential collection of all intraneurysmal AGIs over the acquisition period [9]. In order to prepare the CCTC for mathematical modeling, smoothening and normalization were applied. Rapid intensity fluctuations in the CCTC at the frequency of the heart rate and its higher harmonics were filtered out of the data using a band-stop filter. To normalize the data the point of initial contrast influx into the ROI was set as the initial time point and the amplitude was normalized to unity.

Mathematical Modeling

Following normalization, the CCTC were fitted with Eq. 1 by

| (1) |

minimization of the sum of squares of the error between the data and the model in order to determine optimized values for each parameter. This equation describes the transport of contrast into and out of the aneurysm as a combination of convection and diffusion. The first half of the equation represents convective transport and the second represents diffusive transport. The model consists of six parameters; σ and μ are related to the method of contrast injection; ρconv and ρdiff represent the relative amplitudes of the convective and diffusive portions of the transported contrast, respectively; τconv and τdiff represent the time constants for convection and diffusion and reflect the time the fluid remains within the aneurysm [10]. The mathematical model was fit to the aneurysmal CCTC obtained after implantation of all 6 diverters. The goodness of fit of the mathematical model to the data was evaluated by plotting the model-fits against the data points and calculating the coefficients of determination.

Correlations between the optimized model parameters obtained from angiographic quantification after implantation of each of the 6 diverters and the corresponding intraneurysmal mean kinetic energies obtained from the PIV experiment were investigated.

RESULTS

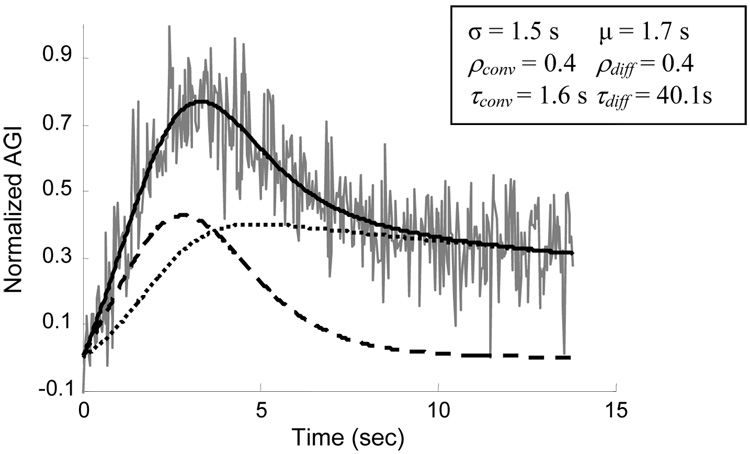

The fit of the model to the transport of contrast into and out of the aneurysm in the case of diverter 4 (70% porosity, 21.2 pores/mm2 pore density) is shown in Fig. 1 as an example. The coefficients of determination between the six CCTCs and the corresponding model fits were greater than 0.7. Since injection of contrast was performed by an automated contrast injection pump with high precision, the parameters σ and μ are not of significance in this experiment. The amplitudes of the convective and diffusive components (ρconv and ρdiff) were not correlated to the mean kinetic energy value (R2 < 0.1).

Figure 1.

Model-fit to the aneurysmal contrast concentration-time curve (gray line) after implantation of diverter 4 (70% porosity, 21.2 pores/mm2 pore density); the dashed line represents the convective process, the dotted line represents the diffusive process and the solid line is the combined process; optimized model parameters are listed; AGI: Average Grayscale Intensity.

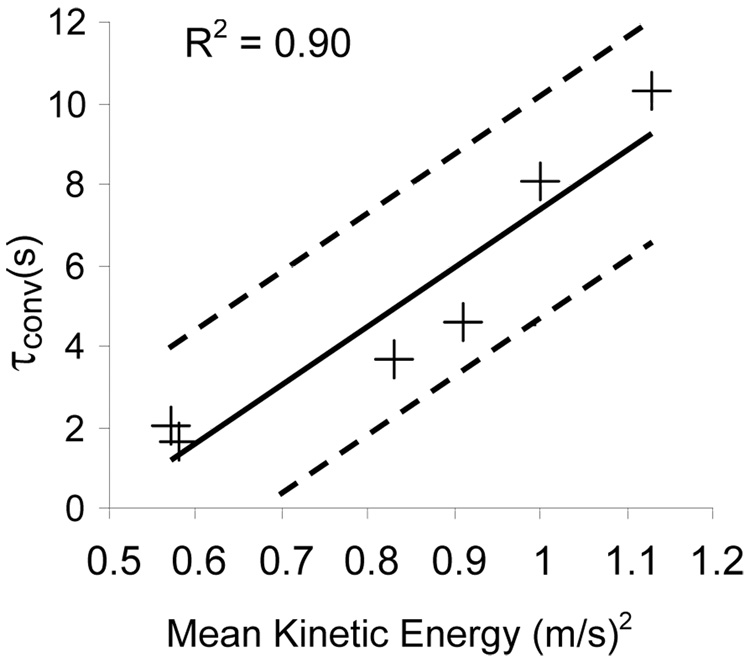

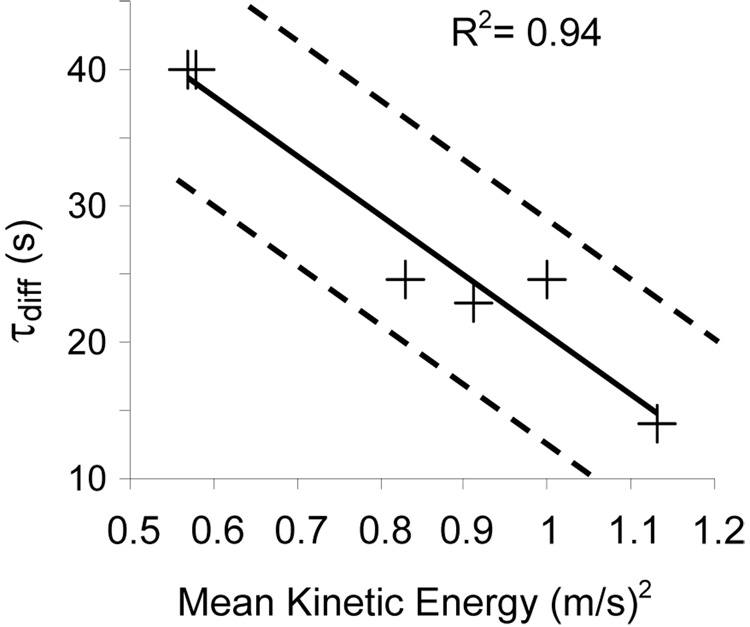

However, the mean kinetic energy within the aneurysm correlated well with both the convection and diffusion time constants (τconv and τdiff). The linear correlation between the mean kinetic energy and the convection time constant is shown in Fig. 2. On the other hand, Fig 3 shows that an inverse linear correlation prevails between the diffusive time constant and the mean kinetic energy.

Figure 2.

Plot of the convective time constant (τconv) versus the mean kinetic energy (+). The solid line represents the linear trend and the dashed lines represent the 95% confidence limit

Figure 3.

Plot of the diffusive time constant (τdiff) versus the mean kinetic energy (+). The solid line represents the linear trend and the dashed lines represent the 95% confidence limit

DISCUSSION

PIV can be considered a gold standard for in vitro measurement of velocity fields within complex geometries such as aneurysms, while DSA can be considered the gold standard for in vivo visualization of geometry and transport within such pathologies. Although various attempts have been made to measure absolute flow parameters using angiography [11], the accuracy of these methods is still lacking especially when the flow fields are complex. We have, however, successfully used angiography to estimate the relative changes in flow transport that occur within aneurysms before and after implantation of flow diverters [9]. In parallel, we have used PIV analysis to obtain quantitative measures such as the intraaneurysmal mean kinetic energy that could be used to evaluate the performance of flow diverters in treating aneurysms [8]. Here, we attempt to establish a correlation between these two modalities in order to provide a better assessment of intraneurysmal flow changes during diverter implantation in the clinical situation.

Implantation of a flow diverter is expected to lower the mean energy within the aneurysm. Larger reductions in the mean kinetic energy signify better decoupling of intraaneurysmal flow from that of the parent artery. In this investigation we demonstrated that in the presence of a flow diverter, a linear correlation exists between the intraneurysmal mean kinetic energy as measured by PIV and the convective and diffusive time constants of intraneurysmal flow exchange as measured by DSA. These correlations indicate that the performance of a flow diverter in reducing the mean kinetic energy inside the aneurysm can be ascertained by evaluating the time that the fluid will remain within the aneurysm. Convective transport is marked by high energy, and therefore longer circulation times of the contrast inside the aneurysm due to convection result in higher kinetic energy values. As the energy of the contrast trapped inside the aneurysm diminishes and the role of diffusion grows, the contrast will be trapped inside the aneurysm for a longer time as shown by the higher values of the diffusive time constant at lower energies. Thus the most effective flow diverter has the lowest intraneurysmal kinetic energy and this is mirrored in the angiographic quantification as the lowest convective residence time and the highest diffusive residence time. Therefore, by analyzing contrast transport alone we can estimate the degree of decoupling between the intraaneurysmal flow from that of the parent artery in the presence of a flow diverting device. The mean kinetic energy within an aneurysm after implantation of a flow diverter may thus be estimated by using the modeling method described here. As the method relies solely on angiographic acquisition, intraneurysmal energy could potentially be estimated in the in vivo and clinical settings.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The study was supported by a National Institutes of Health grant (NS045753-01A1).

Contributor Information

Asher L. Trager, Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Miami, 1251 Memorial Drive, Coral Gables, FL 33146, Email: a.trager@umiami.edu

Chander Sadasivan, Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Miami, 1251 Memorial Drive, Coral Gables, FL 33146, Email: c.sadasivan@umiami.edu

Jaehoon Seong, Department of Engineering and Physics, University of Central Oklahoma, 100 N University Drive, Edmond, OK 73034, Email: jseong@ucok.edu

Baruch B. Lieber, Departments of Biomedical Engineering and of Radiology, University of Miami, 1251 Memorial Drive, Coral Gables, FL 33146, Tel: (305)-284-2330, Fax: (305)-284-6494, Email: blieber@miami.edu

REFERENCES

- 1.American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Dallas, TX: American Heart Association; Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics. 2008

- 2.Marks MP, Dake MD, Steinberg GK, Norbash AM, Lane B. Stent placement for Arterial and Venous Cerebrovascular Disease: Preliminary Experience. Radiology. 1994;191:441–446. doi: 10.1148/radiology.191.2.8153318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wakhloo AK, Lanzino G, Lieber BB, Hopkins LN. Stents for Intracranial Aneurysms: The Beginning of a New Endovascular Era? Neurosurgery. 1998;43:377–379. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199808000-00126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miskolczi L, Guterman LR, Flaherty JD, Hopkins LN. Saccular Aneurysm Induction by Elastase Digestion of the Arterial Wall: A New Animal Model. Neurosurgery. 1998;43(3):595–600. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199809000-00110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cloft HJ, Altes TA, Marx WF, Raible RJ, Hudson SB, Helm GA, Mandell JW, Jensen ME, Dion JE, Kallmes DF. Endovascular Creation of an In Vivo Bifurcation Aneurysm Model in Rabbits. Radiology. 1999;213(1):223–228. doi: 10.1148/radiology.213.1.r99oc15223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seong J, Sadasivan C, Onizuka M, Gounis MJ, Christian F, Miskolczi L, Wakhloo AK, Lieber BB. Morphology of Elastase-Induced Cerebral Aneurysm Model in Rabbit and Rapid Prototyping of Elastomeric Transparent Replicas. Biorheology. 2005;42(5):345–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abruzzo T, Shengelaia GG, Dawson RC, 3rd, Owens DS, Cawley CM, Gravanis MB. Histologic and Morphologic Comparison of Experimental Aneurysms with Human Intracranial Aneurysms. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 1998;19(7):1309–1314. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seong J, Wakhloo AK, Lieber BB. In Vitro Evaluation of Flow Divertors in an Elastase-Induced Saccular Aneurysm Model in Rabbit. J. Biomech. Eng. 2007;129(6):863–872. doi: 10.1115/1.2800787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sadasivan C, Lieber BB, Gounis MJ, Lopes DK, Hopkins LN. Angiographic Quantification of Contrast Medium Washout from Cerebral Aneurysms after Stent Placement. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2002;23(7):1214–1221. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sadasivan C. Ph.D. thesis. Vol. 34. Coral Gables, FL: University of Miami; 2008. Angiographic Assessment of Flow Divertors as Treatment for Cerebral Aneurysms: Results in the Rabbit Elastase-Induced Aneurysm Model; pp. 60–61. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lieber BB, Sadasivan C, Gounis MJ, Seong J, Miskolczi L, Wakhloo AK. Functional Angiography. Crit Rev Biomed Eng. 2005;33(1):1–102. doi: 10.1615/critrevbiomedeng.v33.i1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]