Abstract

The Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) is a widely used cognitive screening measure. The purpose of the present study was to assess how 5 specific clusters of MMSE items (i.e., subscores) correlate with and predict specific areas of daily functioning in patients with dementia. Sixty-one patients with varied forms of dementia were administered the MMSE and an observation-based daily functional test (the Direct Assessment of Functional Status; DAFS). The results revealed that the orientation and attention subscores of the MMSE correlated most significantly with nearly all of the functional domains. The MMSE language items correlated with all but the DAFS shopping and time orientation tasks, while the MMSE recall items correlated with the DAFS time orientation and shopping tasks. Stepwise regression analyses found that among the MMSE subscores, orientation was the single, best independent predictor of most of the DAFS functional domains, with language, attention and recall subscores accounting for additional variance on DAFS functional tasks. These results indicate that the MMSE is not only a good cognitive screening tool, but its specific subsores can predict functional disabilities in patients with dementia.

Keywords: Activities of daily living, functional ability, dementia, Mini Mental State Exam, Direct Assessment of Functional Status

INTRODUCTION

The Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) is among the most popular and widely used of available cognitive screening tests. The MMSE was developed by Folstein, Folstein, and McHough1 as a brief and objective measure for the detection of cognitive functioning, and it is currently available in numerous languages.2 This instrument has demonstrated high reliability, sensitivity to detecting cognitive deficits in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer's disease, and ability to characterize cognitive decline in patients with dementia over time.2 The ease of use and time required for administration (5-10 minutes) makes the MMSE a very desirable screening tool and, in fact, since its introduction, the MMSE has been widely used in clinical and research settings by a variety of healthcare professionals.2 Furthermore, the MMSE is one of the tests recommended by the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS-ADRDA to aid in the diagnosis of probable Alzheimer's disease.3

While it is clear that healthcare professionals find the MMSE to be a useful and informative tool for the detection of cognitive impairment, it is unclear how well the MMSE correlates with patients' actual functional abilities and disabilities. The diagnosis of dementia, in part, requires specific impairments in the patient's daily activities (e.g., work or social functions). However, economic and time limitations preclude assessment of daily functioning of patients, particularly administration of observation-based instruments. Relying on the patient's own report or that of a caregiver/informant regarding daily functional limitations is also problematic4 (i.e., can often lead to an under or overestimation of the patient's true disabilities). As a result, there may be a tendency for clinicians to base the majority of their decision for diagnosis or treatment of dementia on a brief screening tool, such as the MMSE. Thus, establishing the degree to which this brief instrument actually correlates to functional outcome in patients with dementia would be of use to clinicians. To date, only a few studies have been conducted correlating this cognitive screening measure with functional ability tests. In one of the most comprehensive studies, the ECA Piedmont Health Survey found that MMSE scores from 1,637 community-dwelling adults moderately correlated with instrumental activities of daily living (IADL, e.g., shopping, laundry, managing medications), but not physical or basic activities of daily living (ADL) (e.g., eating, dressing, bathing), ADLs5. These findings have been replicated in other studies which suggested that although the MMSE characterizes cognitive impairment, it may not adequately predict other physical ailments in older people, including those with dementia6-8. Warren et al. 9 found relatively strong correlations (r = .64 to .81) between IADLs and the MMSE. In fact, they found that correlations were highest between the MMSE and an observation-based IADL task compared to an IADL questionnaire completed by a person who was well acquainted with the patient. Other studies have found similar results. 10-13 Ford et al. 14 found that the MMSE correlated moderately with basic and instrumental ADL tasks in Caucasian as well as African-American patients with dementia. A study by Reed, Jagust, and Seab, 15 however, found that while the MMSE is a good predictor of IADL functioning in patients with severe dementia, it is not an adequate predictor in patients with mild dementia. They suggested that the MMSE has several limitations and that this brief measure is not suitable for predicting everyday functioning in all patients.

While the above mentioned studies are useful and informative, they have some limitations. They either typically used informant-rated IADL measures or they used observation-based measures but did not conduct in-depth analyses of the specific relationships between MMSE subscores (e.g., cluster of items that assesses specific cognitive aspects such as language or memory skills of the patient) and particular observation-based tests of everyday functional domains (e.g., carrying out financial skills tasks or memory tasks). Requests to make judgments regarding the patient's daily functional ability is routinely made of clinicians, with the underlying assumption that specific cognitive processes, such as memory or language abilities, are involved when performing everyday activities. However, the degree to which various cognitive processes measured by a brief screening measure, such as the MMSE, actually correlated to observed domains of functioning needs to be better understood. For example, it may not be surprising to find that items designed to assess verbal memory on the MMSE have strong associations with everyday tasks that require memory skills (such as shopping); however, how MMSE items correlate to cognitive processes that are required for carrying out other daily routines, such as making financial-based decisions or driving are less intuitive and poorly understood. Thus, the purpose of the current study was to expand on the existing literature by examining how well the MMSE and its various subscores correlate with and predict specific areas of daily functioning in patients with dementia. The current study was not undertaken with the purpose of using the MMSE as a proxy for assessing dementia patient's functional ability. However, given that clinicians have limited time and resources, and typically find themselves administering brief screening measures such as the MMSE, we believe that it would be useful to understand the relationship between MMSE performance and patient's functional abilities.

We hypothesized that 1) while multiple relationships between MMSE subscores (cluster of items that assesses similar underlying cognitive processes, such as memory) and functional abilities will exist, some will be stronger than others, and 2) certain MMSE subscores will better predict circumscribed domains of functioning in patients better than others.

Participants

Sixty-one patients with dementia of various etiologies, including patients with Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia, were included in this analysis. It should be noted that the patients with significant physical disabilities were not included in the current study. However, 4 vascular dementia patients who had very mild hemiparesis, but who were able to perform all MMSE and DAFS tasks who were included in the study. All individuals were participating in a larger NIH-funded research study comparing functional status among demented and non-demented older people. As part of the larger study, participants completed approximately three hours of testing. Tests included an activities of daily living task and a neuropsychological battery that included tests of memory, abstract reasoning, language and information processing domains. The cognitively impaired participants were recruited from four sites, including an Alzheimer's Association Center, a hospital-based geriatric center, a Veterans Administration healthcare center, and a university-based Alzheimer's Disease center.

All participants were referred to the study with a predetermined diagnosis of dementia, based on clinical evaluation by their primary physician and/or neurologist and neuropsychologist. Of the total 61 participants recruited, 36 were diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease, 11 with stroke or vascular dementia, and 14 were given a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual diagnosis of dementia not otherwise specified (NOS). The demographic information for the participants, including age, educational level, and MMSE scores can be found in Table 1. As can be seen from this table, the participants were on average in their eighth decade of life and were relatively well educated. It should be noted that while the patients on average were in the mild range of dementia (based on the group's mean MMSE score), individual patient's MMSE scores ranged from 11 to 30. Specifically, 62% scored greater than 24, 23% scored 23-19, and the remaining 15% scored ≤ 18 on the MMSE.

Table 1.

Mean values for demographic, MMSE, and DAFS scores for all patients.

| Variable+ | Mean | Standard Deviation | Coefficient of Variation (in %) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 72.70 | 8.79 | -- |

| Gender (M/F) | 46/15 | ||

| Education | 15.32 | 3.15 | -- |

| MMSE (0-30) | 23.84 | 4.96 | 20.81 |

| Orientation (0-10) | 8.05 | 1.99 | 24.72 |

| Registration (0-3) | 2.87 | .50 | 17.42 |

| Attention (0-5) | 3.36 | 2.01 | 59.82 |

| Recall (0-3) | 1.41 | 1.20 | 85.11 |

| Language (0-8) | 7.43 | 0.92 | 12.83 |

| DAFS (0-104) | 71.59 | 13.27 | 17.74 |

| Time orientation (0-16) | 12.77 | 4.02 | 31.48 |

| Communication (0-14) | 11.44 | 3.00 | 26.22 |

| Transportation (0-13) | 11.44 | 2.27 | 19.84 |

| Financial (0-21) | 14.95 | 3.23 | 21.61 |

| Shopping (0-16) | 8.25 | 3.68 | 44.61 |

Values within the parenthesis for the MMSE and DAFS represent the range of possible scores a patient can obtain on this test or subscale of the test. Note that scores for the DAFS grooming and eating subscales are not presented given that nearly all participants scored perfectly on these subscales

Measures

The Direct Assessment of Functional Status16 is a performance-based measure of daily activities which was specifically designed to be used in patients with dementia. It is a well validated measure of functional ability with high interrater and test-retest reliability. 16 Additionally, this test has been shown to have adequate convergent and discriminative validity when compared with other ADL measures, such as the Blessed Dementia Rating Scale (r = −.588, p < .01) and the Mini Blessed Dementia Rating (r = −.673, p < .01)16. In this study we also had caregivers' of the patients rate the functional ability of patients using the Lawton & Brody I-ADL measure and found the DAFS total scores correlated significantly with the I-ADL measure (r =.31, p<.05), suggesting adequate validity of the DAFS as a functional assessment tool. This instrument assesses the following seven functional domains: 1) time orientation (orientation to person, place and time and ability to accurately tell time settings on a clock); 2) communication skills (ability to dial a telephone, mail a letter and write a check; 3) transportation skills (ability to identify road signs and driving rules); 4) financial skills (ability to balance a checkbook, write a check, identify currency and count change); 5) shopping skills, (ability to “shop” from a mock grocery store by freely recalling shopping items they have been given 10-minutes prior to the task and, later by selecting items with recognition aids); 6) grooming abilities, (ability to perform basic grooming skills, including combing one's hair and using a toothbrush), and 7) eating ability (ability to use utensils). Examiners presented the specific tasks to the participant and rated their ability based on observed performance. In the present sample, nearly all participants obtained perfect scores on the grooming and eating subscales, therefore the data analyses focused on the DAFS total score and the following five subscales: time orientation, communication, transportation, financial, and shopping skills.

The Mini Mental State Exam1 is a widely used, brief cognitive screening test that assesses patients' global impairment. A total score of 30 is possible on the MMSE. For the purposes of the current study, specific items were summed in order to derive five MMSE subscores. Items on the MMSE tend to cluster so that they assess specific cognitive domains2. For the purposes of this study, we followed procedures used by previous research2 in order to clustered items into the following subcores: 1) orientation: items that assessed individual's orientation to time and place; 2) registration: items that required the ability to register or learn words by accurately repeating three items; 3) attention: items that required attentional skills by performing serial 7′s test or spelling “world” backwards; 4) recall: item that measured short-term verbal memory by requiring recall of three items previously learned in the “registration” section; and 5) language: items that specifically assessed oral and written language reception, repetition, and comprehension. Because the MMSE only has a 1-point item that measures visuospatial/constructional praxis, this item was not used independently or included as part of any of the subscores. While we understand that each item and subscore created in this study does not represent independent cognitive functions, they do tend to be more representative of a specific type of cognitive domain.

Procedures

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the California State University, Northridge and the Veterans Administration Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and their caregivers. All participants were administered the MMSE and the DAFS (performance-based ADL task) during the same testing session. All participants were reimbursed $50 for their participation.

Data Analysis

Demographic characteristics were summarized with descriptive statistics. Bivariate Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated between the MMSE subscales and the DAFS subscales. Given the numerous correlations performed, Bonferroni adjustments were made (.05 divided by the 36 correlation analyses conducted) and an alpha level of .001 was used to determine significance levels of the bivariate correlation coefficients. Then, a series of linear stepwise regression analyses, using the MMSE subscales as the independent variables and the DAFS subscales as the dependent variable, were conducted. These analyses were performed in order to assess which MMSE subscales best uniquely predicted the specific DAFS functional domains. For these analyses a more conservative .01 alpha level was used.

RESULTS

Table 1 presents the average scores patients obtained on the MMSE and the DAFS. The coefficient of variation (calculated as the percentage ratio of standard deviation scores divided by the mean) is also presented for the MMSE subscores and DAFS scales. As can be seen from this table, there was little variation in some of the MMSE subscores (such as registration) and a great deal of variation on others (such as recall and attention).

Results of bivariate Pearson r correlations are presented in Table 2. As can be seen from this table, multiple significant correlations were found between the MMSE and the DAFS. In fact, every MMSE subscore, with the exception of the MMSE registration, correlated significantly with multiple DAFS functional domains. It appears that the MMSE total score and, more specifically, the MMSE orientation subscore correlated with all aspects of the DAFS functional skills. Relative to the other subscores, the MMSE orientation displayed some of the highest correlations with the DAFS functional domains (r values ranging from .53 to .73). The attention subscore of the MMSE also correlated with all but the shopping DAFS task. Similarly, the MMSE language subscale correlated with all DAFS subscores, with the exception of the shopping task and time orientation. Conversely, the MMSE recall subscore only correlated with the DAFS time orientation and shopping tasks, but not the DAFS transportation, communication or financial skills subscales.

Table 2.

Correlation analyses between MMSE and its subscales and DAFS and its subscales.

| DAFS | MMSE Total Score |

MMSE Orientation |

MMSE Registration |

MMSE Attention |

MMSE Recall | MMSE Language |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Score | .79* | .78* | .16 | .52* | .44* | .47* |

| Time orientation | .69* | .73* | .17 | .43* | .44* | .22 |

| Communication | .64* | .62* | .21 | .45* | .21 | .53* |

| Transportation | .63* | .62* | .10 | .42* | .27 | .46* |

| Financial | .64* | .59* | .03 | .51* | .24 | .43* |

| Shopping | .54* | .53* | .13 | .27 | .55* | .22 |

p<.001

The results of the stepwise linear regression are presented in Table 3. These findings indicate that the MMSE orientation subscale is the single, best predictor of all DAFS functional domains. R2 change values provide information regarding the portion of variability each independent variable (MMSE subcores) account in the DV (the DAFS subscales). It is apparent that the orientation subcore uniquely accounted for approximately 8% (shopping) to 53% (time orientation) of the variability in the participants' specific DAFS performances. The MMSE language domain was the second best predictor of DAFS subscales, uniquely accounting for 4% (transportation which was nearly statistically significant at p=.04) to 8% (communication) of the DAFS domains, above and beyond what was accounted for by the MMSE orientation subscale. The MMSE recall subscale accounted for the most variability in participants' DAFS shopping skills (31%), with orientation as the second best predictor for this DAFS subscale (8% variability accounted). The MMSE attention subscale accounted for a portion of variability (7%) in the DAFS financial skills above and beyond what was accounted for by MMSE orientation.

Table 3.

Results of individual stepwise regression analyses using MMSE cluster items as the independent variables to predict DAFS total score and each DAFS subscale as the dependent variables.

| MMSE Variables | Standardized | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAFS | Entered in Equation | Beta | R2 Change | df | F |

| Total Score | Orientation | .78 | .60 | 1, 59 | 89.33** |

| Time orientation | Orientation | .73 | .53 | 1, 59 | 67.32** |

| Communication | Orientation | .47 | .38 | 1, 59 | 36.16** |

| Language | .32 | .08 | 1, 58 | 9.08* | |

| Transportation | Orientation | .51 | .38 | 1, 59 | 36.09** |

| Language | .23 | .04 | 1, 58 | 4.27+ | |

| Financial | Orientation | .44 | .34 | 1, 59 | 30.74** |

| Attention | .30 | .07 | 1, 58 | 8.45** | |

| Shopping | Recall | .38 | .31 | 1, 59 | 25.88** |

| Orientation | .33 | .08 | 1, 58 | 7.33* |

p = .04

p≤.01

p<.001

DISCUSSION

The purpose of the current study was to assess the relationship between specific subscores of the MMSE and functional domains in patients with dementia. Functional domains were assessed with the DAFS, which is an observation-based, rather than an informant- or self-rated measure. The results of the current study support and extend findings of previous research. 10, 14, 15 First, we found the greatest and most significant correlations for the MMSE total score and DAFS functional domains. This was expected, given the previous literature. While this is useful information, we were interested in finding which specific item scores (i.e., subscores) of the MMSE contributed to the correlations found between MMSE total score and DAFS domains. We found a number of significant relationships between the MMSE subscores and patients' actual ability to perform tasks in circumscribed functional domains. The greatest and most significant bivariate relationships were obtained for the MMSE orientation and attention subscores. These cluster items of the MMSE, which consist of only a few items assessing a patients' awareness of place and time, as well as sustained attention, appear to correlate with important functions, such as the ability to tell time, communicate by letter or telephone, recognition of driving rules and signs, financial skills related to balancing a checkbook or writing a check, and carrying out a shopping task from memory or with specific cues. These findings imply that the general disorientation that accompanies dementia impairs just about every aspect of a patients' daily functioning. Additionally, the orientation subset of the MMSE requires interaction, interpretation and memory of environmental information and represents a multi-modal cognitive task. Perhaps this increased complexity is the reason that it is one of the best predictors of all functional domains measured by the DAFS. Similarly, patients with poor sustained/divided attention, are likely to have difficulty in many, if not most, of their everyday daily tasks. Interestingly, the MMSE language subscore was significantly correlated with DAFS functional tasks such as communication, knowledge of transportation signs and rules, and the ability to conduct financial tasks, but not those tasks requiring long- or short-term memory (i.e., time orientation or shopping). Conversely, the MMSE recall items correlated only with tasks that require memory skills, such as shopping and time orientation. While this finding may not be surprising, since the DAFS shopping task does primarily involves memory of shopping items, these findings are interesting for two reasons. First, the MMSE recall subscore requires the patient to recall only 3 items over a very brief period of time (about 2-3 minutes), yet it still captures the memory skills needed to carryout a common daily task. Second, performance on the MMSE recall task does not appear to affect how one carries out other daily abilities, such as communication or financial skills. The overall findings from the correlation analyses are that the MMSE's relationship to functional abilities is not simply global, as suggested in previous research,10, 14, 15 but that specific aspects of the MMSE do in fact correlate more significantly and strongly with certain functional disabilities.

The registration subscale was the only MMSE domain that did not significantly correlate with DAFS total score or individual DAFS subscales. There are two possible reasons for this finding. First, there was very little variation in scores among participants on this subscale (with most obtaining a perfect score), thus, restricting the range for examining relationships between the registration subscale and DAFS. Second, this subscale of the MMSE is simple repetition of three items that are to be stored in short-term memory, and may not be related to any of the complex functional daily skills measured by the DAFS.

The results from the regression analyses demonstrated that it is possible to predict everyday functional competence in dementia patients from their performance on certain MMSE subscores. One of the most significant findings, but perhaps not surprising, was that the MMSE orientation subscore was the single best predictor of all 5 functional dimensions assessed with the DAFS. Also, above and beyond what is accounted for by the orientation subscale, the MMSE language subscale was the next best predictor for 2 out the 5 DAFS domains. Once again, it is clear that the disorientation as well as the lack of language registration and comprehension typically seen in dementia patients produces widespread functional impairments. While these relationships may have been expected, the fact that they can clearly be demonstrated with the MMSE, an instrument with relatively few items, is rather remarkable. Similarly, the MMSE recall subscale, which only contains 3 items, appears to be the single best predictor of the patients' shopping skills. Again, the fact that impairment in recalling 3 items is associated with severe deficits in the ability to carryout a routine shopping task is important.

Our current findings suggest that there is some utility in predicting functional ability in dementia patients with use of the MMSE. Of course, we are not suggesting that the MMSE be administered in place of a comprehensive neuropsychological test battery or observation-based functional tests. Nor are we suggesting that the MMSE be used as a proxy to functional assessment. Neuropsychological test batteries are quite adept at diagnosis and differentiation of dementia,17, 18 and the unique relationship between neuropsychological tests and functional abilities have been clearly demonstrated.19, 20 However, for those healthcare professionals with limited resources who are unable to administer more lengthy tests, the information from this brief measure may be useful for understanding patients' functional limitations.

There are some limitations in the current study that need to be addressed. The first limitation of our study is related to demographic factors. Our sample size was relatively small. However, despite this fact, significant relationships emerged, suggesting that perhaps more robust findings would be obtained with a larger sample. This, of course, needs to be empirically assessed in future studies. Additionally, our sample is relatively well educated with most participants having mild dementia which limits the generalizability of our findings for those less educated individuals in the more advanced stages of dementia until empirically tested. Replication of this study with a less educated sample of more severely demented patients will need to be conducted in order to be able to generalize more patients. Secondly, in the current sample, the ratio of male to female was greater, thus possibly limiting the interpretability of our findings for females. However, it should be noted that the study examined the relationship of cognitive skills and everyday functional ability and found relationships within specific domains. It may be true that males and females perform slightly differently on cognitive tasks and/or ADLs, but the current findings would suggest that a particularly weak cognitive skill results in specific disabilities of daily skills. Of course, further studies using gender as a relevant factor will need to be performed in order to determine what role this variable plays in mediating these relationships. Thirdly, the current study sample had a mixed etiology of dementia. We know from the literature that different cognitive processes are affected depending on the dementia patient's etiology. For example, in the early stages of Alzheimer's dementia, patients predominantly display episodic memory and language deficits, while individuals with cerebrovascular disease present with heterogeneous cognitive deficits (i.e., executive or visual-spatial dysfunction) depending on the site of brain damage. Thus, with the current study we are not able to specify what the relationship between MMSE subscores and functional abilities look like for specific groups of dementia patients. However, the mixed etiology of our sample does allow us to observe varied deficiencies on the MMSE and how these deficits correlate with patient functioning. Thus, while specific predictions regarding functioning cannot be made for a specific patient group, predictions can be made regarding deficits due to cognitive processes. Additionally, a small subset of our patients with cerebrovascular disease (i.e. 4 patients) presented with very mild physical disabilities (hemiparesis). While, their deficits were not great enough to preclude them from participating in the current study (i.e., they were able to perform all MMSE and DAFS tasks), their slight disability may have been a confounding factor for the DAFS performance and future studies should assess these types of patients separately to better understand the unique contribution of physical disabilities. Finally, a larger confirmatory study across a wider spectrum of dementia, or with specific groupings of dementia patients, will need to be carried out in order to better validate the current results.

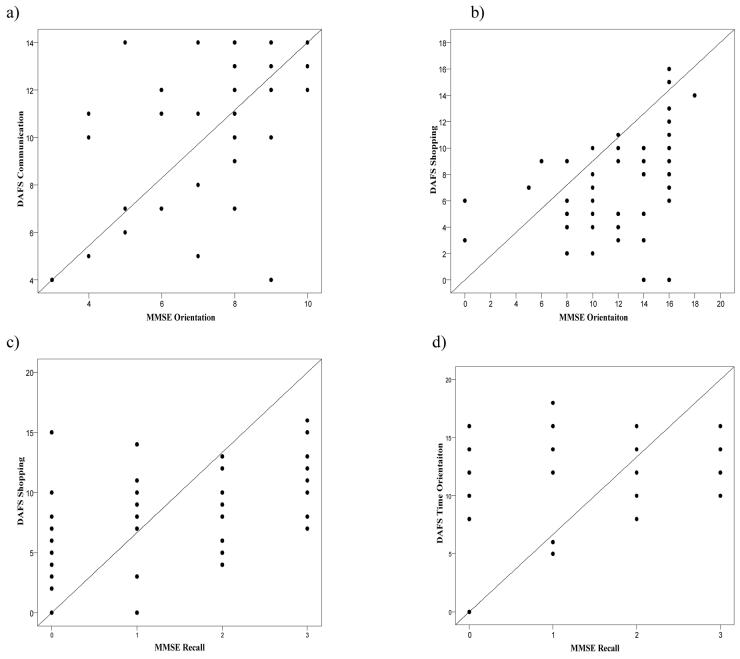

Figure 1.

Scatter plots displaying the correlation between the following four variables: a) MMSE Orientation and DAFS Communication, b) MMSE Orientation and DAFS Shopping, c) MMSE Recall and DAFS Shopping, and d) MMSE Recall and DAFS Time Orientation.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: This study was conducted at California State University, Northridge and was supported by NIGMS grant GM048680 to JR. Additional support for the project was provided by NIGMS grants GM063787 (Minority Biomedical Research Support Program-Research Initiative for Scientific Enhancement) & GM008395 (Minority Access to Research Career).

REFERNCES

- 1.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-Mental State”: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J of Psyc Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tombaugh TN, McIntyre NJ. The Mini-Mental State Examination: A comprehensive review. J Am Ger Soc. 1992;40:935–992. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb01992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, et al. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: Report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pearson V. In: Assessment of Function in Older Adults. Kane R, Kane R, editors. Oxford University Press; New York: 2000. pp. 17–48. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fillenbaum GG, Houghs DC, Heyman A, et al. Relationship of health and demographic characteristics to Mini-Mental State Examination score among community residents. Psyc Med. 1988;18:719–726. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700008412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stern Y, Hesdorffer D, Sano M, et al. Measurement and prediction of functional capacity in Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1990;40:8–14. doi: 10.1212/wnl.40.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bassett SS, Folstein MF. Cognitive impairment and functional disability in the absence of psychiatric diagnosis. Psyc Med. 1991;21:77–84. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700014677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mahrin RK, DeBettignies BH, Pirozzolo FJ. Structured Assessment of Independent Living Skills: Preliminary report of a performance measure of functional abilities in dementia. J Gero. 1991;46:58–66. doi: 10.1093/geronj/46.2.p58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Warren EJ, Grek A, Conn D, Herrmann N, et al. A correlation between cognitive performance and daily functioning in elderly people. J Ger Psyc Neuro. 1989;2:96–100. doi: 10.1177/089198878900200209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vitaliano PP, Breen AR, Russo J, et al. The clinical utility of the dementia rating scale for assessing Alzheimer's patients. J Chron Dis. 1984;37:743–753. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(84)90043-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Winograd CH. Mental status tests and the capacity for self-care. J Am Ger Soc. 1984;34:780–785. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1984.tb05150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nadler JD, Richardson ED, Malloy PF, et al. The ability of the dementia rating scale to predict everyday functioning. Arc Clin Neuropsyc. 1993;8:449–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lecky GS, Beatty WW. Predicting functional performance by patients with Alzheimer's disease using the Problem in Everyday Living (PEDL) test: A preliminary study. J Intl Neuropsych Soc. 2002;8:48–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ford GR, Haley WE, Thrower SL, et al. Utility of Mini-Mental State Exam scores in predicting functional impairment among White and African American dementia patients. J Gero. 1996;51A(4):M185–M188. doi: 10.1093/gerona/51a.4.m185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reed BR, Jagust MD, Seab JP. Mental status as a predictor of daily function in progressive dementia. Gerontologist. 1989;29:805–807. doi: 10.1093/geront/29.6.804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loewenstein DA, Amigo E, Duara R, et al. A new scale for the assessment of functional status in Alzheimer's Disease and related disorders. J Gero. 1989;4:114–121. doi: 10.1093/geronj/44.4.p114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Razani J, Boone K, Miller BL, et al. Neuropsychological Performance of Right- and Left- Frontotemporal Dementia Compared to Alzheimer's Disease. J Intl Neuropsych Soc. 2001;7:468–480. doi: 10.1017/s1355617701744037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pachana NA, Boone K, Miller BL, et al. Comparison of neuropsychological functioning in Alzheimer's disease and frontotemporal dementia. J Intl Neuropsych Soc. 1996;2:505–510. doi: 10.1017/s1355617700001673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farias ST, Harrell CN, Neumann C, Houtz A. The relationship between neuropsychological performance and daily functioning in individuals with Alzheimer's disease: Ecological validity of neuropsychological tests. Arc Clin Neuropsych. 2003;18:655–672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Razani J, Casas R, Wong J, et al. The Relationship Between Executive Functioning and Activities of Daily Living in Patients With Relatively Mild Dementia. App Neuropsych. 2007;14:1–7. doi: 10.1080/09084280701509125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]