Abstract

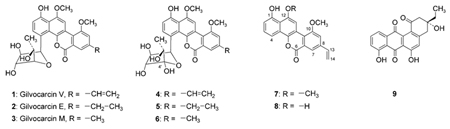

Four new analogues of the gilvocarcin-type aryl-C-glycoside anti-tumor compounds, namely 4′-hydroxy gilvocarcin V (4′-OH-GV), 4′-hydroxy gilvocarcin M, 4′-hydroxy gilvocarcin E and 12-demethyl-defucogilvocarcin V, were produced through inactivation of the gilU gene. The 4′-OH-analogues showed improved activity against lung cancer cell lines as compared to their parent compounds without 4′-OH group (gilvocarcins V and E). The structures of the sugar-containing new mutant products indicate that the enzyme GilU acts as an unusual ketoreductase involved in the biosynthesis of the C-glycosidically linked deoxysugar moiety of the gilvocarcins. The structures of the new gilvocarcins indicate substrate flexibility of the post-polyketide synthase modifying enzymes, particularly the C-glycosyltransferase and the enzyme responsible for the sugar ring contraction. The results also shed light into biosynthetic sequence of events in the late steps of biosynthetic pathway of gilvocarcin V.

Keywords: anti-cancer, biosynthesis, gilvocarcins, glycosylation, pathway engineering, polyketides

Introduction

Gilvocarcin V (GV, 1), the principal product of Streptomyces griseoflavus Gö 3592 and other Streptomyces spp., is the most prominent member of a distinct class of antitumor antibiotics that share a common coumarin-based benzo[d]naphtho[1,2-b]pyran-6-one moiety. This group is often referred to as the gilvocarcin-type anticancer drugs.[1–4] Natural variants within this group are restricted to two regions of the molecule. One variation found is the nature and position of the sugar moiety, which in most cases is C-glycosidically attached to the 4-position, with the exception of BE-12406 A and B; these contain an O-glycosidically linked l-rhamnose at the 12-position.[5,6] The other, more restricted variation lies in the side chain at the 8-position, which can consist of a vinyl, ethyl or methyl group. Often, mixtures of compounds in a particular producer strain were found to differ only in this 8-side chain. The vinyl-derivative is the predominant analogue, and the sugar moieties are unique for each producing organism.[7–10] GV is one of the strongest antitumor compounds among these anticancer drugs, however, the exact molecular mechanisms of its anti-cancer activity remain obscure. The most likely mechanism of action is a photoactivated [2+2]cycloaddition of its vinyl side chain with thymine residues of the DNA caused by near-UV or visible blue light, which results in single strand scissions, and covalent binding to DNA.[11–13] In addition, GV mediates selective crosslinking between DNA and histone H3, a core component of the histone complex[14] that plays an important role in DNA replication and transcription. This crosslinking is believed to contribute significantly to GV’s unique mechanism of action, as GV shows a stronger antitumor activity compared to other vinyl side chain containing members of the gilvocarcin-type group of antibiotics.[15,16] A problem associated with the gilvocarcin-type drugs is their poor solubility. The drugs are practically insoluble in water and all organic solvents except DMSO. Since the vinyl side chain is responsible for DNA-binding, one can assume that the other side of the GV molecule plays a major role in binding to histone H3, particularly the unique C-glycosidically linked d-fucofuranose moiety, which contains all chiral elements of the molecule. Thus, modification of the sugar moiety might improve the activity of the drugs and also lead to an analogue with improved solubility. In order to manipulate this sugar moiety it was necessary to identify and characterize its encoding genes.

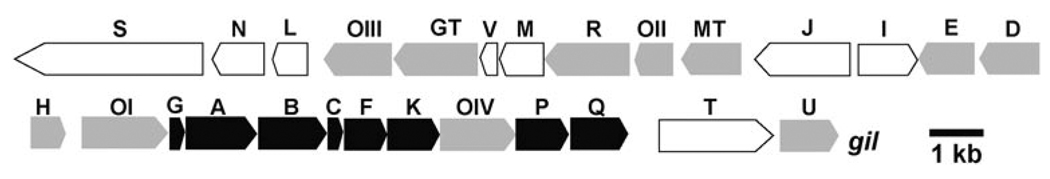

The vast majority of deoxysugars found in polyketide producers are pyranoses, while five-membered furanoses are rare. The gene cluster encoding the biosynthesis of gilvocarcin V (Figure 1) contains only a few genes that could be safely assigned from alignment studies to encode enzymes responsible for the formation of the d-fucofuranose moiety of GV.[4]

Figure 1.

The gil gene cluster, with white-depicted genes involved in regulation or encoding enzymes of unknown function, black genes responsible for the assembly of the polyketide backbone, and gray genes encoding enzymes that catalyze post-PKS-tailoring steps (oxidations, reductions, deoxysugar biosynthesis, glycosyltransfer).

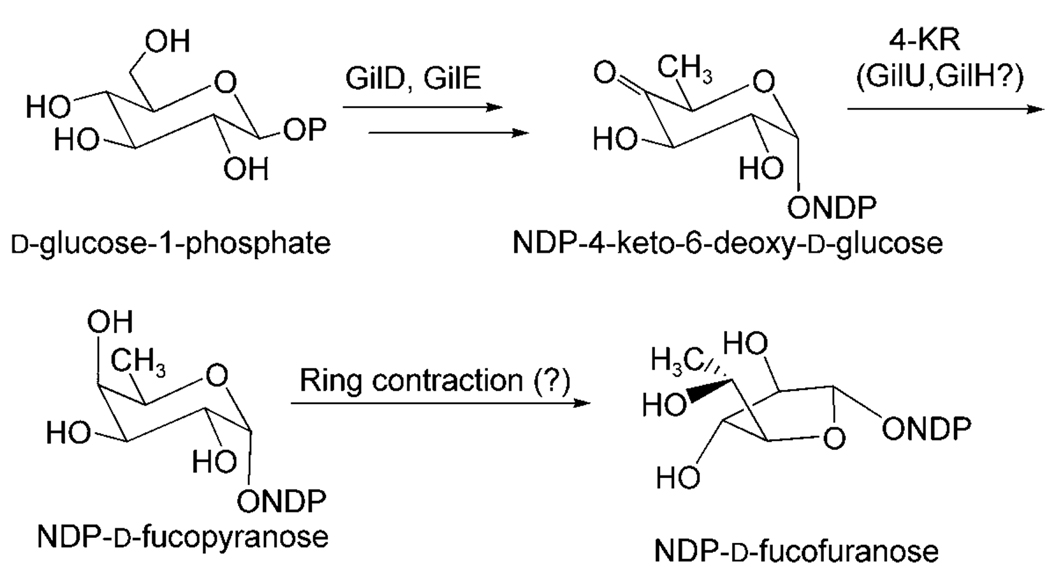

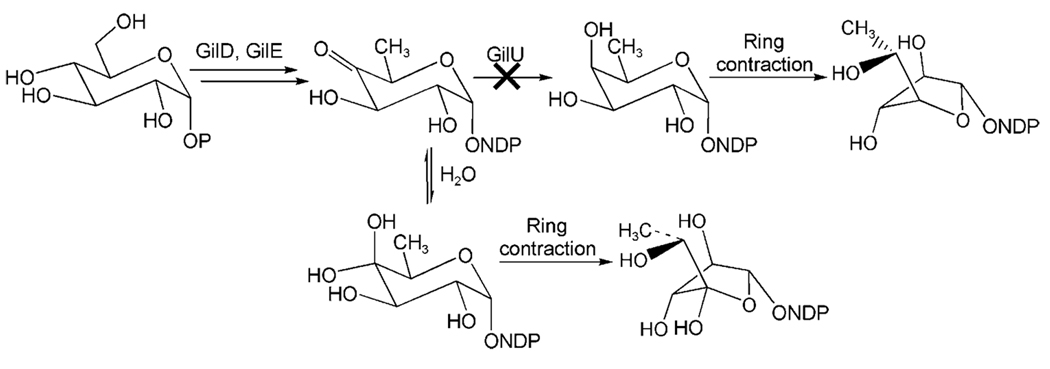

Two of these crucial genes, gilD and gilE, encode nucleosyldiphosphate (NDP) glucose synthase and 4,6-dehydratase, respectively, two key enzymes found in the biosynthesis of all 6-deoxysugars. These two enzymatic steps lead to the formation of the biosynthetic key intermediate NDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-d-glucose through NDP-activated d-glucose. The next logical step would be a ketoreduction, which establishes the axial 4-OH group, before a rearrangement of the resulting pyranose to the furanose finishes the preparation of the NDP-d-fucofuranose donor substrate of the glycosyltransferase GilGT (Scheme 1). The products of three genes of the gil gene cluster were possibly responsible for this crucial 4-ketoreduction step, although none of the corresponding genes showed significant similarity with typical 4-ketoreductase encoding genes found in deoxysugar pathways. These genes are: 1) gilR, apparently an oxidoreductase encoding gene located far upstream of the PKS (polyketide synthase) genes between gilM and gilOII, 2) gilH, a reductase gene found immediately downstream of gilE and gilD, and 3) gilU located at the end of the gil cluster. A recent inactivation experiment that affected gilR showed that its product, GilR, is involved in the establishment of the lac-tone moiety of GV, particularly the oxidation of pregilvocarcin V into GV, which is the last step in GV biosynthesis.[17] The gilU gene appeared to code for an epimerase or dehydratase, which also might function as a ketoreductase or contribute in some way to the 4-ketoreduction and be involved in sugar bio-synthesis (see below). gilH seemed to encode a NADPH-dependent reductase.[4] To investigate which of these two genes is involved in the biosynthesis of GV’s sugar moiety and to possibly generate new gilvocarcins with altered sugar moieties, gilH and gilU were inactivated.

Scheme 1.

Proposed pathway for the NDP-sugar donor substrate of glycosyltransferase GilGT.

Results and Discussion

Deletion of gilH and gilU

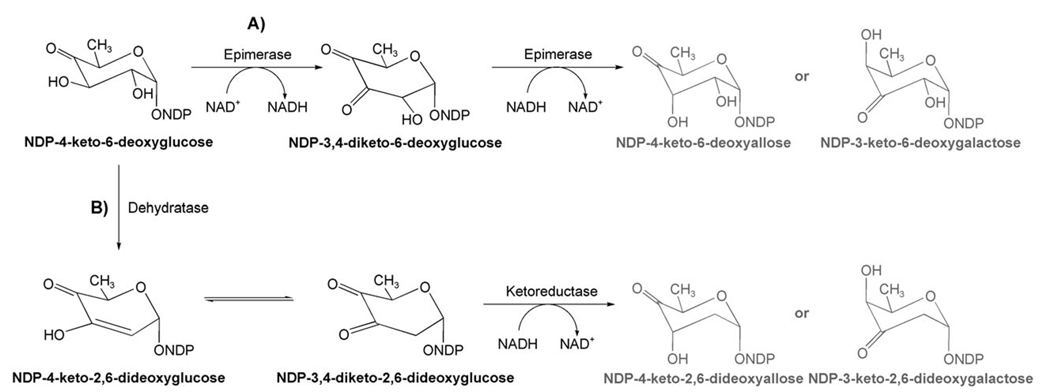

The deduced amino acid sequence of gilH has no similarity with 4-ketoreductases typically found for deoxyhexose biosyntheses. However, GilH showed high identity (similarity) with NADH:FMN reductases, specifically with JadY (64 % amino acid (aa) identity, 74 % similarity; accession number AAL82807) from the jadomycin pathway from Streptomyces venezuelae,[18–20] and with putative reductases from Sorangium cellulosum (55 % aa identity, 72 % similarity; accession number YP_001612518) as well as from Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) (57 % aa-identity, 68 % similarity; accession number NP_630351). A specific function has not been assigned yet for any of these enzymes. Experiments with overexpressed, purified and His6-tagged GilH showed that it contained non-covalently bound FAD. Deletion of the gilH gene in cosmid cosG9B3 (containing the apramycin (Apr)-resistance cassette and the entire gilvocarcin V gene cluster)[4] was achieved using the PCR-targeting REDIRECT method,[21–23] which we previously used successfully for inactivation of various gil genes,[17,24,25] as well as for the inactivation of gilU (see below). However, the resulting mutant strain S. lividans TK24 (cosG9B3-H−) showed the same production pattern as the gilvocarcin producer S. lividans (cosG9B3). Thus the inactivation of gilH had no effect on the gilvocarcin biosynthesis. Overall, the experiments clearly refuted the involvement of GilH in the biosynthesis of the gilvocarcin deoxyfucose moiety, which suggests that GilH may be an NADH:FAD reductase in GV pathway, which provides reduced cofactors for the oxygenases GilOI and GilOIV.[17,25] Similarly, the deduced amino acid sequence of gilU has also no similarity to 4-ketoreductases typically found in gene clusters encoding deoxysugar biosyntheses. However, it shows some resemblance to (putative) NDP-sugar epimerases (36 % aa identity with WcqD of Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. michiganensis NCPPB 382, gene bank accession number NC009480.1, 31 % aa identity with TM0509 from Thermotoga maritima, gene bank accession number AAD35594,[26,27] 28% aa-identity with a putative NDP-sugar epimerase of Saccharopolyspora erythraea NRRL 2338, gene bank accession number NC009142.1) as well as to NDP-glucose-4,6-dehydratases (e.g., 28% aa-identity with SpcI from S. netropsis; gene bank accession number U70376). Both types of enzymes belong to the family of NAD+-dependent epimerases/dehydratases, which are also related to the short chain dehydrogenase/reductase (SDR) superfamily.[28,29] Members of this family have a common NAD+-binding domain in the terminal part of the protein and two highly conserved tyrosine and lysine residues. These two amino acids are essential for the catalytic activity of SDR enzymes. Epimerases and dehydratases create similar reaction products, although their mechanisms are quite different. Assuming that the substrate is NDP-4-keto-6-deoxyglucose (Scheme 2), one would expect either NDP-3,4-diketo-6-deoxyglucose or NDP-3,4-diketo-2,6-dideoxyglucose as the initial products of GilU, depending on whether GilU acts as an epimerase or as a dehydratase (i.e., follows path A or B in Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Expected deoxysugar pathway if GilU would act A) as an epimerase or B) as a dehydratase/4-ketoreductase. The gray labeled products would be expected to become the sugar donor substrates of the gil pathway, which is not the case.

However, both reaction sequences end up with wrong products, namely in the first case an NDP-keto-6-deoxysugar, and in the second case an NDP-keto-2,6-dideoxysugar. Also, in the reaction sequence shown in Scheme 2, path B (dehydration followed by ketoreduction), is usually catalyzed by two enzymes, for example, GraOrf27 and GraOrf26 or their analogues.[30] As a simple alternative, GilU just might be a truncated enzyme that catalyzes only the second, namely the ketoreduction step of the reactions shown in Scheme 2, and might act directly on NDP-4-keto-6-deoxyglucose as 4-ketoreductase.

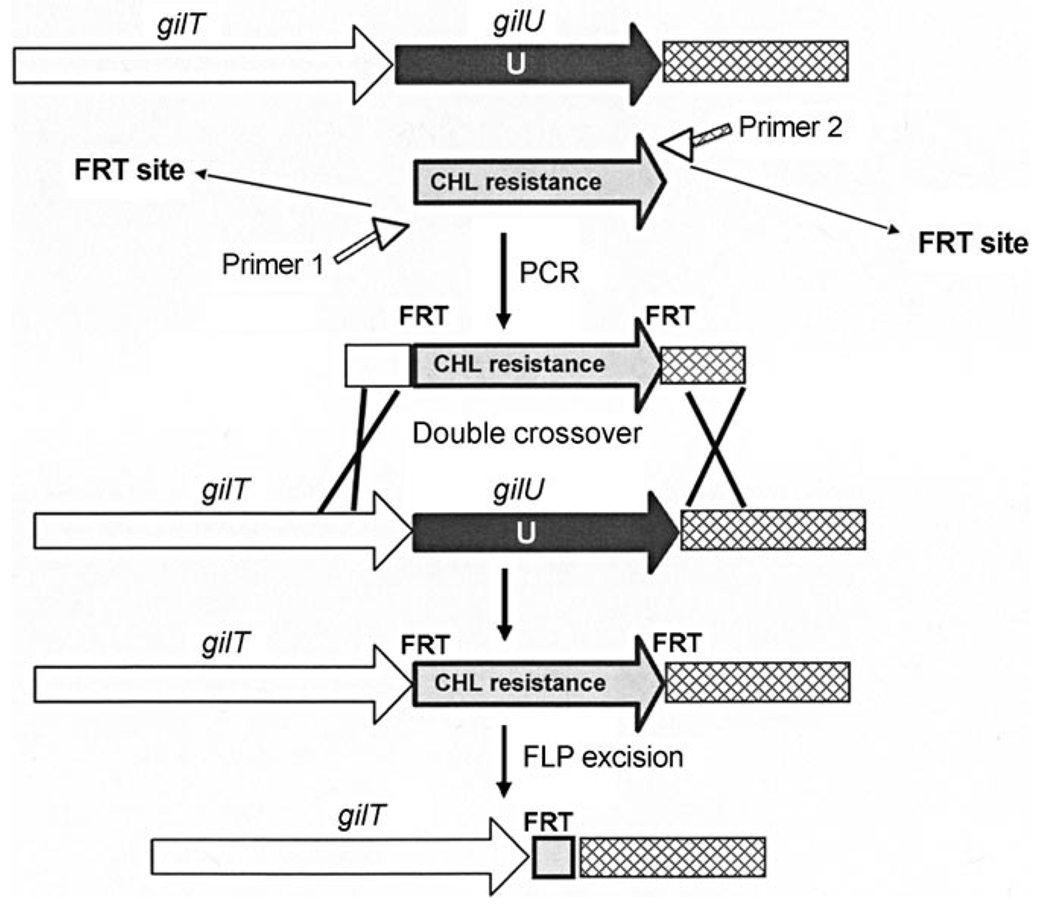

To narrow down the alternatives discussed above, GilU was inactivated through gene deletion. The inactivation of gilU in cosG9B3 was modified using the PCR-targeting method mentioned above.[17,22,24,25] The coding sequence of GilU was replaced by the chloramphenicol (CHL) resistance cassette through double crossover. In the following FLP-mediated excision of the CHL resistance cassette, mutants were selected for Apr-resistance and CHL-sensitivity (Figure 2). The cultures of one of these mutants, S. lividans TK24 (cosG9B3-U−), showed no production of gilvocarcins V and M. Instead, various other compounds accumulated in the strain. Since gilU is located at the end of the gil gene cluster, a polar effect on downstream genes, as was found after gilGT inactivation,[24] was not possible.

Figure 2.

Application of the Redirect PCR targeting system in CosG9B3 for the inactivation of gilU. FRT: FLP (flippase) recognition target; CHL: chloramphenicol resistance gene; primer 1: gilU_FRT_rev; primer 2: gilU_FRT_forw.

Isolation and structure elucidation of the products accumulated by the GilU-minus mutant S. lividans TK24 (cos9B3-U−)

The compounds were purified by preparative HPLC, and their structures were determined by NMR and mass spectroscopy. The GilU-minus mutant S. lividans TK24 (cosG9B3-U−) accumulates one major product, defucogilvocarcin V (7, 10 mg L−1), and six minor compounds, 4′-hydroxygilvocarcin V (4, 0.5 mg L−1), 4′-hydroxygilvocarcin E (5, 0.2 mg L−1), 4′-hydroxygilvocarcin M (6, 0.2 mg L−1), 12-demethyl-defucogilvocarcin V (8, 0.2 mg L−1), and homorabelomycin (9, 0.5 mg L−1). The known compounds 7 and 9 were identified through HPLC-MS, and from their 1H NMR and UV spectra.[25,31]

Compound 4 exhibits all of the typical NMR signals of the gilvocarcin V-chromophore,[32] but differs in its sugar moiety. The positive FAB mass spectrum shows a molecular ion at m/z 510.0 [533.1 [M+Na]+], which corresponds to a mass difference of + 16 amu compared to gilvocarcin V,[32] and thus supports a structure with one more oxygen atom (that is, an additional OH group in the sugar moiety). This additional OH group in the sugar moiety was also evident after D2O exchange in the 1H NMR spectrum. Three of the OH groups of the sugar residue appear as a doublet (they show H/OH coupling with a geminal H-atom, and are thus secondary alcohol functions) while the forth appears as a singlet. The former were assigned to the hydroxy groups in the 2′-, 3′- and 5′-positions, respectively, while the singlet with a chemical shift of δ = 5.24 Hz must be derived from a 4′-OH. Other assignments are not possible, because one would expect 2 OH-singlets, if the additional OH group were located in 2′-, 3′-or5′-position. In addition, the 4-H signal found in the 1H NMR spectrum of GV (1) was missing here. All H,H-coupling constants of the sugar moiety are in a 5–7 Hz range, which is typical for a five-membered ring. In conclusion, the sugar moiety of compound 4 was identified as 4-hydroxy-fucofuranose, and structure 4 as 4′-hydroxy-gilvocarcin V. This structure is also strongly supported by additional NMR data (see Table 3), which reveal a quaternary carbon in the 13C NMR spectrum (δC 102.2 s, typical for a hemiketal). This hemiketal carbon also shows a strong 3JC–Hcoupling with 6′-CH3 of the sugar in the HMBC spectrum. The observation of a strong NOE coupling between 4′-OH and the 3′-OH group also proves the shown absolute configuration of the 4-hydroxy-fucofuranose moiety.

Table 3.

1H NMR (400 MHz) and 13C NMR (100.6 MHz) data for 4′-hydroxy-gilvocarcin V (4) in [D6]DMSO (relative to internal TMS, J in Hz).

| Position number | 1H δ | 13C δ | HMBC correlation | COSY | NOESY |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-OH | 9.67, S | 153.2 | 1, 2, 12a | ||

| 2 | 6.89, d (8.4) | 112.7 | 1, 4, 12a | 3 | 3 |

| 3 | 8.02, d (8.4) | 128.7 | 1, 4a, 1′ | 2 | 2 |

| 4 | 127.5 | ||||

| 4a | 124.7 | ||||

| 4b | 143.1 | ||||

| 6 | 160.4 | ||||

| 6a | 123.7 | ||||

| 7 | 7.96 d, (1.6) | 119.8 | 6, 9, 10a, 13 | ||

| 8 | 139.2 | ||||

| 13-H | 6.92, dd (17.6, 11.2) | 135.9 | 7 | 14-He, 14 Hz | 14-He, 14 Hz |

| 14-He | 6.11, d (17.6) | 117.9 | 8 | 13-H | 13-H, 14 HZ |

| 14HZ | 5.46, d (11.2) | 8 | 13-H | 13-H, 14-He | |

| 9 | 7.71, d (1.6) | 115.0 | 7, 10, 10a, 13 | ||

| 10 | 158.1 | ||||

| 10-OCH3 | 4.14, s | 57.5 | 10 | ||

| 10a | 123.1 | ||||

| 10b | 113.5 | ||||

| 11 | 8.44, s | 102.2 | 4b, 10a, 10b, 12a, 12b | ||

| 12 | 152.5 | ||||

| 12-OCH3 | 4.08, s | 57.0 | 12 | ||

| 12a | 115.6 | ||||

| 1′ | 6.30, d (6.4) | 79.1 | 3 | 2′ | 2′ |

| 2′ | 4.81, dd (6.4, 6.4) | 78.1 | 3′ | 1′, 3′ | 2′-OH |

| 2′-OH | 4.50, d (6.4)* | 3′ | 2′ | ||

| 3′ | 3.87, t (6.4) | 77.56 | 2′ | 2′, 3′-OH | 3′-OH |

| 3′-OH | 4.90, d (6.4)* | 3′ | 3′ | ||

| 4′-OH | 5.23, s* | 102.2 | 3′,4′ | 3′-OH, 5′-OH | |

| 5′ | 3.68, dq (6.4, 5.6) | 69.0 | 6′-CH3 | 6′-CH 3 | |

| 5′-OH | 4.85, d (5.6)* | 5′ | 5′ | ||

| 6′-CH3 | 1.22, d (6.4) | 17.8 | 4′, 5′ | 5′ | 5′ |

Signals exchangeable with D2O.

Compound 5 differs from compound 4 only in that it is missing the 8-vinyl group. Instead, a saturated 8-ethyl residue can be observed in the 1H NMR spectrum as known from gilvocarcin E (2)[15] at δ = 2.82 (q, J = 8 Hz), 1.29 (t, J = 8 Hz, Table 4).The chemical shifts and coupling constants of all other 1H NMR signals are almost identical with those of compound 4. Thus, compound 5 was identified as 4′-hydroxy-gilvocarcin E. The structure is also supported by its UV spectrum which resembles that of gilvocarcins M and E rather than that of gilvocarcin V[32] and the FAB mass spectrum, which shows a molecular ion peak at m/z 512.2.

Table 4.

1H NMR (400 MHz) data for 4′-hydroxy-gilvocarcin E (5), 4′-hydroxy-gilvocarcin M (6), 12-demethyl-defucogilvocarcin V (8) and defucogilvocarcin V (7, for comparison) in [D6]DMSO (relative to internal TMS, J in Hz).

| Position | Multiplicity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 6 | 8 | 7 | |

| 1-OH | 9.70, s | 9.70, s | ** | 9.54, s |

| 2 | 6.91, d (8) | 6.90, d (8) | 6.80, dd (7.5, 1) | 6.98, dd (8.4, 1.2) |

| 3 | 8.04, d (8) | 8.04, d (8) | 7.44, t (7.5) | 7.53, t (8.4) |

| 4 | 7.83, dd (7.5, 1) | 7.90, dd (8.4, 1.2) | ||

| 7 | 7.80, d (1.6) | 7.79, br s | 8.0, d (1.2) | 8.02, d (1.5) |

| 9 | 7.53, d (1.6) | 7.51, br s | 7.71, d (1.2) | 7.74, d (1.5) |

| 10-OCH3 | 4.13, s | 4.12, s | 4.12, s | 4.17, s |

| 11 | 8.49, s | 8.48, s | 8.23, s | 8.40, s |

| 12-OH | ** | |||

| 12-OCH3 | 4.12, s | 4.12, s | 4.11, s | |

| 13-H | 2.82, q (8) | 2.5, s* | 6.92, dd (11.4, 17.4) | 6.93, dd (11.4, 17.4) |

| 14-H | 1.29, t (8) | He 6.13, d (17.4) | He 6.15, d (17.4) | |

| Hz 5.48, d (11.4) | Hz 5.50, d (11.4) | |||

| 1′ | 6.34, d (6.8) | 6.33, d (6.4) | – | – |

| 2′ | 4.85, dd (6.8, 6.8) | 4.84, dd (6.8, 6.4) | – | – |

| 2′-OH | 4.51, d (6.8) | 4.50, d (6.8) | – | – |

| 3′ | 3.92, t (6.8) | 3.92, t (6.8) | – | – |

| 3′-OH | 4.91, d (6.8) | 4.92, d (6.8) | – | – |

| 4′-OH | 5.25, s | 5.24, s | – | – |

| 5′ | 3.72, dq (6.4, 5.2) | 3.72, dq (6.4, 5.2) | – | – |

| 5′-OH | 4.87, d (5.2) | 4.86, d (5.2) | – | – |

| 6′-CH3 | 1.24, d (6.4) | 1.25, d (6.4) | – | – |

Signal obscured by solvent

not observed signals because of overlap with H2O

Compound 6 exhibits the typical gilvocarcin M type UV spectrum.[32] Also the 1H NMR data (Table 4) and molecular ion peak at m/z 499.0 in the positive-mode APCI-MS spectrum suggest a gilvocarcin M skeleton chromophore[32] with the same 4′-OH fucofuranose moiety as found in compounds 4 and 5. Thus, compound 6 was identified as 4′-hydroxy-gilvocarcin M.

The structure of compound 8 was deduced from its mass spectral and 1H NMR data (Table 4). The deprotonated molecular ion peak at m/z 332.9 in the negative-mode APCI-MS spectrum indicates a molecular weight (Mw = 334) 14 amu smaller than defucogilvocarcin V (7)[25] and thus indicates a structure with one of the methyl groups missing. The 1H NMR data of 8 resembles those of 7 except for the disappearance of one O-methyl group. The upfield-shifted 2-H (δ = 0.13) and 11-H (δ = 0.17) suggests that the 12-O-methyl group is missing. Thus, the structure of compound 8 was deduced as 12-demethyl-defucogilvocarcin V.

The new compounds 4, 5 and 6 bear an extra OH group in 4′-position, which indicate that a hydrated 4-keto-intermediate plays a role in the biosynthesis of these three mutant products. This is proof that the enzyme GilU, which was deleted in this mutant, is responsible for the 4-ketoreduction step. In absence of GilU, a hydrate is formed that also can undergo rearrangement into the five-membered furanose form (Scheme 1). Thus, it must be assumed that an NDP-d-fucopyranose is an intermediate for the biosynthesis of the β-d-fucofuranose moiety of GV (1, Scheme 1). A subsequent SN2-reaction, catalyzed by a not yet identified enzyme, in which 4-O replaces 5-O as the ring oxygen, would give rise to the five-membered furanose ring. The resulting stereochemistry in the 4-position is in agreement with the observed stereochemistry for the β-d-fucofuranose moiety in gilvocarcin V. Two additional arguments support this postulated reaction mechanism. First, gilvocarcin V has been shown to undergo an acid-catalyzed rearrangement to a major product with a β-d-fucopyranose sugar moiety and a minor compound, which was identified as the α-d-fucopyranose isomer of GV due to a partly occurring SN1 reaction.[33] This shows that the fucopyranose and fucofuranose ring structures are inter-convertible, predominantly in an SN2 fashion, even without enzyme catalysis. Secondly, one can assume from the close structural relationship between the gilvocarcins, ravidomycins, chrysomycins, and Mer compounds[7,8,16,34–37] that all these compounds evolved from a common ancestral origin and share a common set of biosynthetic genes. While the Mer sugar moiety[7,8,38] is still in the unreduced state (4-keto group) the ravidomycin[7,39–41] and chrysomycin[42–45] sugars are both pyranoses with an axial 4-OH group. It is therefore likely that all of these pathways inherited the same set of three basic deoxysugar enzymes, namely an NDP-d-glucose synthase and a NDP-d-glucose-4,6-dehydratase (GilD and GilE in the gil pathway), plus an unusual GilU-like 4-ketoreductase, which generates the axial 4-OH group of the NDP-fucopyranose intermediate of the gil pathway as well as the axial 4-OH residues in the pyranose moieties of chrysomycin and ravidomycin, whose pathways are currently under investigation in our lab.

The accumulation of defucogilvocarcin V as the major product of the GilU− mutant S. lividans TK24 (cosG9B3-U−) showed that the biosynthesis of the d-fucofuranose moiety of the gilvocarcins was significantly disturbed by inactivation of GilU. The fact that gilvocarcins with 4′-hydroxy-fucofuranose moieties emerged as minor products, shows that both the rearrangement enzyme as well as the glycosyltransferase GilGT,[24] have some relaxed substrate specificity. Obviously, the rearrangement to the furanose can only occur after hydration of NDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-d-glucose, which presumably was accumulated in the mutant upon inactivation of GilU. The hydrate formation generates an axial OH group that can undergo the SN2-reaction discussed above. The resulting NDP-4-hydroxy-d-fucofuranose is stereoelectronically similar to the normal substrate of GilGT, and can be attached by GilGT (Scheme 3). However, the low yield found for these 4′-hydroxy-gilvocarcin analogues indicate that either the rearrangement enzyme or GilGT or both have some problems with the NDP-4-hydroxy sugars. Note that a hydrate form of 4-keto-d-olivose was also observed upon inactivation of 4-ketoreductase in certain mithramycin analogues.[16] d-rhodinose, which is normally not biosynthesized, was also found in the new metabolite urdamycin M upon inactivation of 4-ketoreductase gene urdR of the urda-mycin gene cluster.[46] To the best of our knowledge, the 4-hydroxy-d-fucofuranose is the first new five-membered ring sugar moiety of a polyketide-glycoside generated by genetic engineering. Since the additional 4-OH group in the furanose moiety of 4 might enhance its hydrogen bonding with a cellular target (likely histone H3[15,16]), an increased antitumor activity was possible. Compound 4 also shows improved solubility compared to 1 and is slightly soluble in methanol, while 1 is not.

Scheme 3.

Biosynthetic pathway of NDP-d-fucofuranose (upper path) and generation of 4′-hydroxy-d-fucofuranose upon inactivation of GilU via hydrate formation (lower branch).

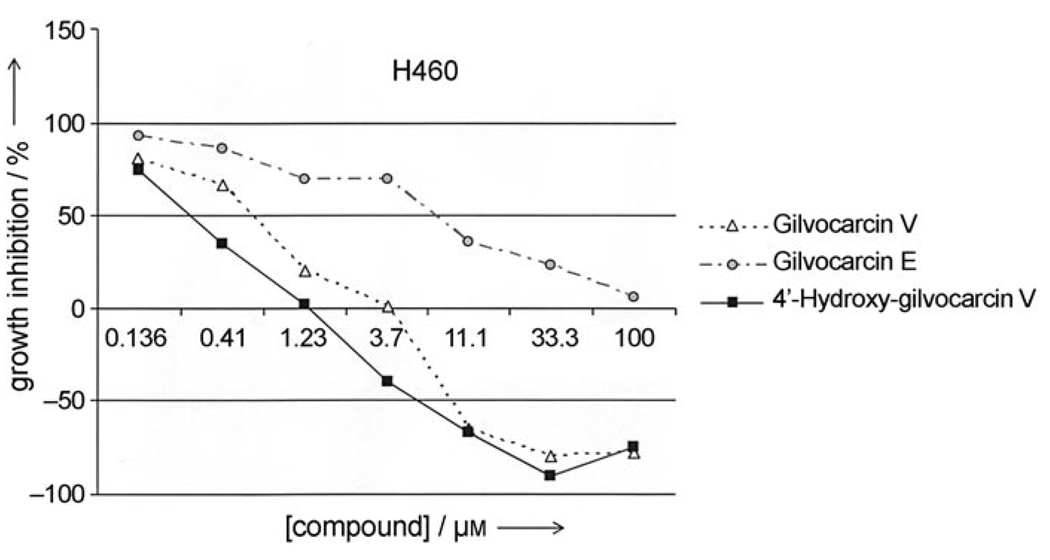

Anticancer activity

Preliminary anticancer assays against a human breast (MCF-7), a human lung (H460) and a murine lung cancer cell line (LL-2) indicated that the 4′-hydroxygilvocarcins 4 and 5 have similar (MCF-7, LL/2) to slightly better (H460) anticancer activity than their parental analogues 1 and 2 (Table 1). As expected, the activities of analogues 2 and 5, which lack the for the DNA binding essential vinyl residue, are much lower. Nevertheless, the introduction of the 4′OH group changed a rather inactive drug (2) into a moderately active one (5). Dose dependence curves further support the advantage of the 4′OH group. For example, Figure 3 shows the dose-dependent activity of 4′-hydroxy-gilvocarcin V (4, squares, solid line) against the human lung cancer cell line H460 in comparison with gilvocarcin V (1, triangles, dotted line) and gilvocarcin E (2, solid circles, semi-dotted line).

Table 1.

Anticancer activity assays[a] of gilvocarcins.

| Gilvocarcins | Anticancer activity (% T/C at 100 µm)[b] | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| H460 | MCF-7 | LL/2 | |

| Gilvocarcin V (1) | 5.5 ± 0.3 | 4.5 ± 1.0 | 1.4 ± 0.4 |

| 4′-OH-Gilvocarcin V (4) | 2.6 ± 0.5 | 7.0 ± 2.5 | 1.4 ± 0.5 |

| Gilvocarcin E (2) | 34.5 ± 8.5 | 47.7 ± 1.1 | 30.4 ± 6.9 |

| 4′-OH-Gilvocarcin E (5) | 8.0 ± 1.6 | 15.1 ± 5.4 | 16.6 ± 3.5 |

Figure 3.

Concentration-dependent activity of 4′-hydroxy-gilvocarcin V (■)in comparison with gilvocarcins V (△) and E (○).

The steeper decline of the 4-hydroxy-gilvocarcin V (4, Figure 3) data line indicates a higher potency than gilvocarcin V (1). For instance, the GI50 of 4 is ~0.3 µm versus ~0.75 µm for 1, or the total growth inhibition (TGI) in presence of 4 occurs already at concentrations of ~1.25 µm, compared to a TGI of > 3.7 µm for patented drug 1.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the work described here reveals that GilU is responsible for the 4-ketoreduction that occurs during the generation of the d-fucofuranose moiety of gilvocarcin V (GV, 1). The experiment also proves indirectly that the unique d-fucofuranose is derived from d-fucopyranose by ring contraction. Five new compounds were generated as a result of the inactivation experiment, some with partly improved biological activity and solubility compared to their parent drugs. The work also sheds light into the late steps biosynthetic sequence of events of GV, and these results also provide important additional information regarding the substrate specificity of several post-PKS enzymes involved in biosynthesis of GV. For instance, the experiments described here reflect the flexibility of glycosyltransferase GilGT and of the enzyme responsible for the intriguing sugar ring contraction to form the unique structure of d-fucofuranose. However, it is still unclear whether GilGT[24] attaches d-fucopyranose or d-fucofuranose to the polyketide-derived core of the gilvocarcin aglycon, and whether the ring contraction occurs after or before the glycosyl transfer step. The more likely scenario is that the ring contracting enzyme acts first, and GilGT transfers a furanose, either with or without 4-hydroxy group. Otherwise GilGT would need to transfer a 4-keto sugar, a flexibility rarely observed among GTs of secondary metabolism.[49–52] Further investigation of GilGT and the ring contracting enzyme, once identified, will solve this ambiguity. Such a ring contracting enzyme could be useful in generating new furanose moieties from other pyranose moieties with axial 4-OH groups, like those found in chrysomycin and ravidomycin.

The fact that 4′-hydroxy-gilvocarcin M (6) was also isolated is not surprising, since S. lividans TK24 (cosG9B3) produces significant amounts of gilvocarcin M (3) besides its principal product gilvocarcin V (1). However, the accumulation of 4′-hydroxy-gilvocarcin E (5) is somewhat surprising, since S. lividans TK24 (cosG9B3) does not produce noticeable amounts of gilvocarcin E (2). The production of 5 by S. lividans TK24 (cosG9B3-U−) might indicate feedback inhibition of GilOIII,[24] the enzyme responsible for the vinyl group formation earlier in the biosynthesis, which might be inhibited by the accumulated defucogilvocarcin V (7). Also compound 9 is a shunt product, which might be caused by a feedback effect, as we reported previously.[25]

From the presence of defucogilvocarcin V (7) it might be concluded that C-glycosylation is the last step in the biosyn-thesis of GV (1). However, glycosylation could also occur earlier in the biosynthesis, for example, before the O-methylation steps, the vinyl group and/or the lactone formation.[17] The accumulation of 7 may just reflect a certain degree of substrate flexibility of the enzymes governing O-methyltransfer, and vinyl and lactone formation, insofar as these enzymes may be able to recognize substrates missing the sugar moiety. Past biosynthetic studies revealed that the C-glycosylation occurs later than the oxidative 5,6-C/C-bond cleavage of the proposed intermediate homo-2,3-dehydro-UWM 6, which is a key step for the formation of the unique chromophore of the gilvocarcins.[17,25] The accumulation of 12-demethyl-defucogilvocarcin V (8) indicates that the vinyl group formation occurred earlier than at least one of the O-methylation steps in the biosynthesis of 1.

Experimental Section

Bacterial strains, cosmids and culture conditions

Cosmid cosG9B3 is pOJ446-derived and contains the entire gilvocarcin gene cluster.[4]

Streptomyces lividans TK24 was routinely cultured on M2 agar plates containing agar (1.5 %), glucose (0.4 %), malt extract (1 %), yeast extract (0.4 %) and CaCO3(0.1 %) up to sporulation, and spores were stocked in glycerol (20 %) and used for conjugation. YT broth (2×), containing tryptone (1.6 %), yeast extract (1 %) and sodium chloride (0.5 %), pH 7.0, was used during conjugation.

Escherichia coli XL1 Blue MRF’ (Stratagene) was used for propagation of plasmids, cosmids and grown in liquid at 220 rpm or on solid Luria-Bertani medium containing tryptone (1 %), yeast extract (0.5 %), sodium chloride (1 %), agar (1.5 %), pH 7.0, at 37°C.

The REDIRECT® technology kit containing E. coli ET12567, E. coli ET12567/pUZ8002, E.coli BW25113, pKD20, pIJ790 and pCP20 was a gift from Plant Bioscience Ltd. (Norwich, United Kingdom).

Apramycin (50 µg mL−1), chloramphenicol (25 µg mL−1), nalidixic acid (25 µg mL−1), carbenicillin (100 µg mL−1) and kanamycin (50 µg mL−1) were used for selection of recombinant strains.

DNA isolation, manipulation and cloning

Standard procedures for DNA isolation and manipulation were performed according to Sambrook and Russel[53] and Kieser et al.[54] Isolation of DNA fragments from agarose gels and purification of PCR products was carried out using the QIA quick® Gel Extraction kit (Qiagen, California, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Isolation of the mutated derivatives of cosmidG9B3 was carried out using ion exchange columns (Nucleobond AX kits, Macherey–Nagel, PA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Inactivation of gilU and gilH

The disruption gene cassette was amplified using formerly generated CHL gene cassette combined with primer pair GilU_FRT_for and GilU_FRT_rev (Table 2). Underlined letters represent 39 nt homologous extensions to the DNA regions immediately upstream and downstream of gilU, respectively, including the putative start and stop codons of gilU. The cassette was introduced into E. coli BW25113/pKD20, containing cosmid G9B3 (Apr-resistant), which included the entire biosynthetic gene cluster of gilvocarcin V. The disrupted cosmid (G9B3) containing the chloramphenicol resistance cassette was introduced into E. coli XL-Blue MRF’/pcp20 encoding the FLP recombinase to remove the central part of disruption cassette. Apr-resistant, chloramphenicol-sensitive colonies were identified by replica plating and verified by PCR analysis using a pair of primers GilU_Ctrl_forw and GilU_Ctrl_rev (Table 2). While the original gilU PCR products from cosG9B3 showed products of 1136 bp, respectively, the mutant with the chloramphenicol resistance gene gave PCR products of 1095 bp. After FLP-mediated excision of the disruption cassette, PCR products of 275 bp were obtained (Figure 2). The mutated cosG9B3 was introduced into Streptomyces lividans TK24 by conjugation from E. coli ET12567 carrying the non-self transmissible helper plasmid pUZ8002 as described by Kieser et al.[54] An identical protocol was followed to inactivate the gilH gene in cosG9B3 using GilH_FRT_for, GilH_FRT_rev, GilH_Ctrl_forw, and GilH_Ctrl_rev primers (Table 2).

Table 2.

Oligonucleotide primers used in inactivation and expression experiments.

| Name of primer | Oligonucleotide sequence |

|---|---|

| GilU_FRT_forw | 5′-GAGGCACTCCTGTCGTCGAGAGAGCACGGCCCCACGGTGATTCCGGGGATCCGTCGACC-3′ |

| GilU_FRT_rev | 5′-TGATGTGCGGCCTGGGTCTTTTGTCGTTCGTGTGGCTCATGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC-3′ |

| GilOIV_Ctrl_forw | 5′-CCGCGTTCTTCCGTATGC-3′ |

| GilOIV_Ctrl_rev | 5′-CTTAGCTCAGATGGCCAGAGC-3′ |

| GilH_FRT_forw | 5′-TTCGAGAGCTCGGTCCCTACCGAAGGAGCGAAACAGATGATTCCGGGGATCCGTCGACC-3′ |

| GilH_FRT_rev | 5′-ACGTTCACCAGGGGGTCCGGCGGGCGGACCGGTGCGTCATGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC-3′ |

| GilH_Ctrl_forw | 5′-CTCATAATCTGGCCGCTC-3′ |

| GilH_Ctrl_rev | 5′-AACGTGCTGGTCACGGCCCTC-3′ |

| GilH_ex_forw | 5′-GAGCGGAATTCATGATCAGGATCGCCGTCATCCTC-3′ |

| GilH_ex_rev | 5′-CGGAAGCTTGTGCGTCACACCGACACGGCCCGGCC-3′ |

Heterologous production and co-factor analysis of GilH

A pair of primers (GilH_ex_for and GilH_ex_rev, Table 2) was used to amplify gilH from cosG9B3 using pfu-polymerase (Stratagene) and the product was cloned into PCR®-Blunt II-TOPO® vector. The positive clone was sequenced to confirm that no mutation had been introduced during gene amplification. The gilH fragments excised from the TOPO construct with EcoRI and HindIII were cloned at the identical sites of pRSETB vector (Invitrogen) to generate an expression construct pGilH. The plasmid was transformed into E. coli BL21-(DE3). The seed culture (10 mL) of a colony was inoculated into 1 L of LB medium supplemented with ampicillin (100 µg mL−1). The culture was grown at 37°C until OD600 reached to 0.6. IPTG (0.1 mm final concentration) was added to the culture, and the fermentation was continued for 8 h at 23°C. The pellets were collected through centrifugation (6000 g, 10 min), washed with 50 mm potassium phosphate buffer (pH. 7.6) and disrupted by ultrasonication. The crude GilH fraction that was obtained through centrifugation (12 000 g, 20 min) was purified through immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC). The concentration of the enzyme was determined to be 4 mg mL−1 following the Bradford protein assay method. 4 mg (1 mL) of GilH was boiled for 5 min and the denatured protein was removed by centrifugation (10 000 g, 10 min). The supernatant was taken for HPLC and UV-spectral analyses. Aqueous solutions (1 mL, 0.5 mm) of standard FAD, FMN and NAD+ were taken as positive controls, and 50 mm phosphate buffer supplemented with 150 mm imidazole was used as a negative control.

Analysis, isolation and characterization of products accumulated by S lividans TK24 (cosG9B3-U−)

S. lividans TK24 (cosG9B3-U−) was cultured in SG medium (glucose (20 g L−1), soy peptone (10 g L−1), CaCO3,(2 g L−1), and CoCl2(1 mg L−1) at pH 7.2 prior to sterilization) supplemented with Apr. This pre-culture was grown for 1 day at 30°C and 220 rpm, and was subsequently used to inoculate the main culture of the same composition, which was harvested after 4 days of shaking as above. The culture broth was extracted three times with equal volumes of ethyl acetate. Extracts were dried in vacuo, dissolved in methanol and examined by HPLC-MS.

Purification was achieved by semi-preparative HPLC. HPLC/MS was performed on a Waters Alliance 2695 system with Waters 2996 photodiode array detector and a Micromass ZQ 2000 mass spectrometer equipped with an APCI ionization probe (solvent A = 0.1 % formic acid in H2O; solvent B = acetonitrile; flow rate = 0.5 mL min−1; 0–6 min 75 % A and 25 % B to 100 % B [linear gradient], 7.5–10 min 75 % A and 25 % B). Semi-preparative HPLC was run on a Waters Delta 600 instrument with a Waters 996 photodiode array detector (Solvent A = H2O; solvent B = acetonitrile; 0–2 min 100 % A and 0 % B, 2–4 min 100 % A to 60 % A and 40 % B[linear gradient], 4–30 min 60 % A and 40 % B to 45 % A and 55 % B [linear gradient], 30–32 min 45 % A and 55 % B to 100 % B [linear gradient]. 32–36 min 100 % B, 36–38 min 100 % A [linear gradient], 38–52 min 100 % A. The columns used for HPLC were Waters Symmetry C18, 4.6×50 mm, particle size 5 µm (HPLC/MS), and Waters Symmetry PrepTM C18, 19×150 mm, particle size 5 µm (semi-prep HPLC).

Physicochemical data of new compounds

The structures of the new metabolites 4′-hydroxy-gilvocarcins V, E and M (4–6) and of 12-demethyl-defucogilvocarcin V (8) were identified by using spectroscopic methods, through a combination of the NMR spectra, the UV- and MS data. NMR spectra were acquired on a Varian Inova 400 instrument at a magnetic field strength of B0 9.4 T. For the NMR data see Table 3 and Table 4. Chemical shifts are reported in ppm relative to internal TMS.

4′-Hydroxy-gilvocarcin V (4)

1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): see Table 3; 13C NMR (100.6 MHz, [D6]DMSO): see Table 3; UV λmax (from HPLC-diode array) 249 (98 %), 288 (100 %), 397 (36 %); HR-FAB (m/z 533.1409; calcd. for C27H26O10Na: 533.1424).

4′-Hydroxy-gilvocarcin E (5)

1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): see Table 4; UV λmax (from HPLC-diode array) 245 (100 %), 276 (70 %), 387 (22 %); HR-FAB (m/z 512.1702; calcd. for C27H28O10: 512.1682).

4′-Hydroxy-gilvocarcin M (6)

1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): see Table 4; UV λmax (from HPLC-diode array) 245 (88 %), 276 (71 %), 388 (21 %); Positive APCI (m/z 499; C26H27O10 [M+H+]).

12-Demethyl-defucogilvocarcin V (8)

1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): see Table 4; UV λmax (from HPLC-diode array) 248 (98 %), 288 (100 %), 392 (29 %); Positive APCI (m/z 335; C20H15O5 [M+H+]).

Cytotoxicity assays

In vitro cytotoxicity against human lung H460, human breast MCF-7 and murine Lewis lung (LL-2) cell lines were assessed using the sulforhodamine B (SRB) assay, after 48 h exposure to the drugs.[47,48] % T/C = percent cell mass compared to control without drug; GI50 = 50 % growth inhibition; TGI = total growth inhibition.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant (CA 102102) from the US National Institutes of Health. The University of Kentucky core facilities for NMR and mass spectrometry are acknowledged for the use of their instruments.

References

- 1.Nakano H, Matsuda Y, Ito K, Ohkubo S, Morimoto M, Tomita F. J. Antibiot. 1981;34:266–270. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.34.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takahashi K, Yoshida M, Tomita F, Shirahata K. J. Antibiot. 1981;34:271–275. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.34.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balitz DM, O’Herron FA, Bush J, Vyas DM, Nettleton DE, Grulich RE, Bradner WT, Doyle TW, Arnold E, Clardy J. J. Antibiot. 1981;34:1544–1555. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.34.1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fischer C, Lipata F, Rohr J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:7818–7819. doi: 10.1021/ja034781q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kojiri K, Arakawa H, Satoh F, Kawamura K, Okura A, Suda H, Okanishi M. J. Antibiot. 1991;44:1054–1060. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.44.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakajima S, Kojiri K, Suda H, Okanishi M. J. Antibiot. 1991;44:1061–1064. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.44.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamashita N, Shin-ya K, Furihata K, Hayakawa Y, Seto H. J. Antibiot. 1998;51:1105–1108. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.51.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakashima T, Fujii T, Sakai K, Tomohiro S, Kumagai H, Yoshioka T. United States Patent 6,030,951. United States: Mercian Corporation (JP); 2000

- 9.Narita T, Matsumoto M, Mogi K, Kukita K, Kawahara R, Nakashima T. J. Antibiot. 1989;42:347–356. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.42.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krohn K, Rohr J. Top. Curr. Chem. 1997;188:127–195. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arce R, Oyola R, Alegria AE. Photochem. Photobiol. 1998;68:25–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alegria AE, Zayas L, Guevara N. Photochem. Photobiol. 1995;62:409–415. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1995.tb02361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGee LR, Misra R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:2386–2389. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eickbush TH, Moudrianakis EN. Biochemistry. 1978;17:4955–4964. doi: 10.1021/bi00616a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsumoto A, Fujiwara Y, Elespuru RK, Hanawalt PC. Photochem. Photobiol. 1994;60:225–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1994.tb05095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsumoto A, Hanawalt PC. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3921–3926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kharel MK, Zhu L, Liu T, Rohr J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:3780–3781. doi: 10.1021/ja0680515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang LR, McVey J, Vining LC. Microbiology. 2001;147:1535–1545. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-6-1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang L, Vining LC. Microbiology. 2003;149:1991–2004. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26209-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang KQ, Han L, He JY, Wang LR, Vining LC. Gene. 2001;279:165–173. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00723-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.USA. 2000;97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gust B, Challis GL, Fowler K, Kieser T, Chater KF. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:1541–1546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337542100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cherepanov PP, Wackernagel W. Gene. 1995;158:9–14. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00193-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu T, Kharel MK, Fischer C, McCormick A, Rohr J. ChemBioChem. 2006;7:1070–1077. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200600031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu T, Fischer C, Beninga C, Rohr J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:12262–12263. doi: 10.1021/ja0467521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sterner R, Dahm A, Darimont B, Ivens A, Liebl W, Kirschner K. EMBO J. 1995;14:4395–4402. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00118.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nelson KE, Clayton RA, Gill SR, Gwinn ML, Dodson RJ, Haft DH, Hickey EK, Peterson JD, Nelson WC, Ketchum KA, McDonald L, Utterback TR, Malek JA, Linher KD, Garrett MM, Stewart AM, Cotton MD, Pratt MS, Phillips CA, Richardson D, Heidelberg J, Sutton GG, Fleischmann RD, Eisen JA, Fraser CM, et al. Nature. 1999;399:323–329. doi: 10.1038/20601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kallberg Y, Oppermann U, Jornvall H, Persson B. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002;269:4409–4417. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jornvall H, Persson B, Krook M, Atrian S, Gonzalez-Duarte R, Jeffery J, Ghosh D. Biochemistry. 1995;34:6003–6013. doi: 10.1021/bi00018a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dräger G, Park SH, Floss HG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:2611–2612. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Misra R, Tritch HR, Pandey RC. J. Antibiot. 1985;38:1280–1283. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.38.1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takahashi K, Tomita F. J. Antibiot. 1983;36:1531–1535. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.36.1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jain TC, Simolike GC, Jackman LM. Tetrahedron. 1983;39:599–605. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hirayama N, Takahashi K, Shirahata K, Ohashi Y, Sasada Y. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1981;54:1338–1342. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hosoya T, Takashiro E, Matsumoto T, Suzuki K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:1004–1015. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Knobler RM, Radlwimmer FB, Lane MJ. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:4553–4557. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.17.4553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morimoto M, Okubo S, Tomita F, Marumo H. J. Antibiot. 1981;34:701–707. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.34.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takashi N, Tadashi F, Kazuya S, Tomohiro S, Hiroyuki K, Takeo Y. United States Patent 6030 951. United States: Mercian Corporation; 2000

- 39.Futagami S, Ohashi Y, Imura K, Hosoya T, Ohmori K, Matsumoto T, Suzuki K. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:1063–1067. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hsu D-S, Matsumoto T, Suzuki K. Synlett. 2005;2005:801–804. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arai M, Tomoda H, Tabata N, Ishiguro N, Kobayashi S, Omura S. J. Antibiot. 2001;54:562–566. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.54.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hart DJ, Merriman GH, Young DGJ. Tetrahedron. 1996;52:14437–14458. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Farr RN, Kwok DI, Daves J, G D. J. Org. Chem. 1992;57:2093–2100. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weiss U, Yoshihira K, Highet RJ, White RJ, Wei TT. J. Antibiot. 1982;35:1194–1201. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.35.1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wei TT, Byrne KM, Warnick-Pickle D, Greenstein M. J. Antibiot. 1982;35:545–548. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.35.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hoffmeister D, Ichinose K, Domann S, Faust B, Trefzer A, Dräger G, Kirschning A, Fischer C, Künzel E, Bearden DW, Rohr J, Bechthold A. Chem. Biol. 2000;7:821–831. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)00029-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rubinstein LV, Shoemaker RH, Paull KD, Simon RM, Tosini S, Skehan P, Scudiero DA, Monks A, Boyd MR. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1990;82:1113–1118. doi: 10.1093/jnci/82.13.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Skehan P, Storeng R, Scudiero D, Monks A, McMahon J, Vistica D, Warren JT, Bokesch H, Kenney S, Boyd MR. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1990;82:1107–1112. doi: 10.1093/jnci/82.13.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Remsing LL, Garcia-Bernardo J, Gonzalez AM, Künzel E, Rix U, Braña AF, Bearden DW, Méndez C, Salas JA, Rohr J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:1606–1614. doi: 10.1021/ja0105156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gonzalez A, Remsing LL, Lombó F, Fernandez MJ, Prado L, Braña AF, Künzel E, Rohr J, Méndez C, Salas JA. Mol. Gen. Genet. 2001;264:827–835. doi: 10.1007/s004380000372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Salah-Bey K, Doumith M, Michel JM, Haydock S, Cortes J, Leadlay PF, Raynal MC. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1998;257:542–553. doi: 10.1007/s004380050680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thibodeaux CJ, Melancon CE, Liu H-w. Nature. 2007;446:1008–1016. doi: 10.1038/nature05814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sambrook J, Russel DW. Molecular Cloning. A Laboratory Manual. 3rd ed. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kieser T, Bibb MJ, Buttner MJ, Chater KF, Hopwood DA. Practical Streptomyces Genetics. Norwich, UK: The John Innes Foundation; 2000. [Google Scholar]