Abstract

In jawed vertebrates most expressed immunoglobulin H chains use only one of six possible DH reading frames. Reading frame 1 (RF1), the preferred reading frame, tends to encode tyrosine and glycine, whereas the other five RFs tend to be enriched for either hydrophobic or charged amino acids. Mechanisms proposed to favor use of RF1 include a preference for deletion over inversion that discourages use of inverted RF1, RF2 and RF3; sequence homology between the 5’ terminus of the JH and the 3’ terminus of the DH that promotes rearrangement into RF1; an ATG start site upstream of RF2 that permits production of a truncated Dμ protein; stop codons in RF3; and, following surface expression of IgM, somatic, presumably antigen receptor-based selection favoring B cells expressing Igs with tyrosine and glycine enriched CDR-H3s. By creating an IgH allele limited to the use of a single, frameshifted DFL16.1 DH gene segment, we tested the relative contribution of these mechanisms in determining reading frame preference. Dμ-mediated suppression via an allelic exclusion-like mechanism dominated over somatic selection in determining the composition of the CDR-H3 repertoire. Evidence of somatic selection for RF1-encoded tyrosine in CDR-H3 was observed, but only among the minority of recirculating, mature B cells which use DH in RF1. These observations underscore the extent to which the sequence of the DH acts to delimit the diversity of the antibody repertoire.

Introduction

Among the six complementarity determining regions (CDRs) that make up the antigen binding site in immunoglobulins, it is the CDR-3 of the H chain that most often plays a defining role in antigen recognition and binding (1-3). This key role reflects the location of CDR-H3 at the center of the antigen binding site, as classically defined, as well as the two rounds of N addition permitted by the inclusion of a diversity (D) gene segment (4,5).

In theory, the inclusion of a D gene segment coupled with random insertion of N nucleotides should produce a CDR-H3 repertoire of random diversity. This permissive role of the D has been referred to as D-diversity (6). In practice, tyrosine and glycine are heavily overrepresented in CDR-H3, comprising 30−40% of the global amino acid content of this hypervariable interval. Many of these tyrosines and glycines are provided to CDR-H3 by use of DH reading frame 1, which is normally favored (7-15). This preference for RF1 has the effect of disenfranchising almost two-thirds of all DJ rearrangements, which at first glance appears extremely wasteful. This has led to the suggestion that the expression of DH in RF2 might be incompatible with effective antigen recognition and downstream B cell signaling, a concept referred to as D-disaster (6).

Mechanistically, the normal preference for RF1 has been linked to RF-specific properties and sequence motifs that are shared among twelve of the thirteen DH gene segments in BALB/c mice. These include a predilection for rearrangement by deletion, the frequent occurrence of stop codons in RF3 which act to reduce the likelihood of creating an open reading frame among VDJ rearrangements that use RF3, a bias towards rearrangement at sites of sequence microhomology between the 5’ end of the JH and the 3’ end of the DH which favor rearrangement into RF1, and an ATG start site upstream of RF2 that permits production of a truncated Dμ protein (9,16-19). The DQ52 gene segment, which contributes to less than 5% of the repertoire, shares none of these features and use of RF1 is less pronounced.

Transgenic studies have shown that the bias against RF2 can be released when pre B cells are no longer able to produce membrane bound Dμ protein, suggesting that this μ H chain variant can engage the mechanisms of allelic exclusion to inhibit subsequent V→DJ rearrangement (20). However, the extent to which the bias for tyrosine and glycine in CDR-H3 reflects genetic control of DH reading frame rearrangement preferences remains unclear; as does the extent to which somatic selection during B cell development might adjust the repertoire should use of RF2-encoded amino acids yield a D-disaster (6).

In order to address the role of DH sequence in regulating RF usage and CDR-H3 amino acid content, we evaluated the composition of the CDR-H3 repertoire among developing B cells in the bone marrow of mice limited to use of a single, mutated, frameshifted DH DFL16.1. The first of two mutations shifts the Dμ open reading frame from RF2 to RF1. The second shifts the region of DH-JH microhomology from RF2 to RF1 and at the same time shifts one of two TAG codons from RF3 to RF1. We show that these two frameshift mutations completely transfer the preference for RF1 to RF2 among progenitor B cells. Although we do find evidence of selection for DH RF1 sequence content in mature B cells, this effect appears limited to that minority of the mature B cell population which uses RF1. For the majority of cells, we show that Dμ-mediated suppression via an allelic exclusion-like mechanism dominates over DH sequence composition in shaping the diversity of the CDR-H3 repertoire in mice. Our results support the view that the D gene segment serves to delimit as well as to diversify the composition of the CDR3-centric antigen binding site repertoire, effectively maintaining the repertoire within what appears to be an evolutionarily preferred range thereby avoiding D-disaster (6,14).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of targeted ES cells and the ΔD-DμFS mouse

The methods used to create the IgH ΔD-DμFS allele were identical to those previously used to create the ΔD-DFL and ΔD-iD alleles (14,15) with the following exception. An 800 base pair BglII fragment containing DFL16.1, the kind gift of Dr. Y. Kurosawa (Fujita Health University, Japan) (8), was modified by PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis to include a thymidine nucleotide at the 5’ terminus of the DFL16.1 gene segment (position 1 from the 5’ end), and a second thymidine nucleotide six nucleotides from the 3’ terminus (position 19 from the 5’ end, Figure 1) (21). The ESDQ52-KO cell line, which was derived from wild-type BALB/c-I ES cells of the IgHa haplotype (22), was again targeted. This cell line contains a loxP site in lieu of a 240 base pair XhoI-SacI fragment containing the DQ52 gene and a putative 5’ cis-regulatory element. By Southern blot analysis and DNA sequencing, one ES clone was identified to contain both the DμFS and the DQ52-deleted mutations. Following injection into C57BL/6J blastocysts, a chimeric DμFS-containing male was bred to a BALB/cJ hCMV-cre transgenic female to delete all but DμFS in the DH locus. The integrity of the mutant DH allele was then confirmed by Southern blot and DNA sequencing.

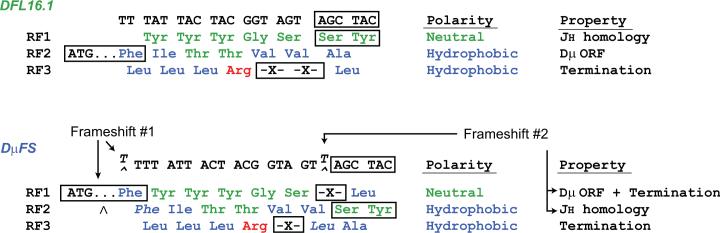

Figure 1. Two frameshift mutations were used to shift DH reading frame bias from RF1 to RF2.

In the targeting construct, a thymidine (T) was inserted at the 5’ terminus of DFL16.1, the most VH-proximal DH (33). This insertion placed reading frame 1 in frame with the upstream Dμ ATG start site (20). A second thymidine was inserted six bases upstream of the 3’ terminus of DFL16.1. This insertion placed reading frame 2 in frame with terminal codons for serine and tyrosine that share sequence with the 5’ termini of three of the four JH gene segments (7,9).

Mice were maintained in a specific pathogen–free barrier facility. All experiments with live mice were approved by and performed in compliance with IACUC regulations.

Flow cytometric analysis and cell sorting

Flow cytometric analysis and cell sorting was performed as previously described on cells from bone marrow (12,14,15). A MoFlo instrument (Cytomation, Ft. Collins, CO) was used for cell sorting. Cells were independently sorted from the bone marrow of two homozygous ΔD- DμFS and two wild-type siblings (eight weeks old). Developing B lineage cells in the bone marrow were identified on the basis of surface CD19, CD43, IgM, BP-1, and IgD (Figure 2) (23).

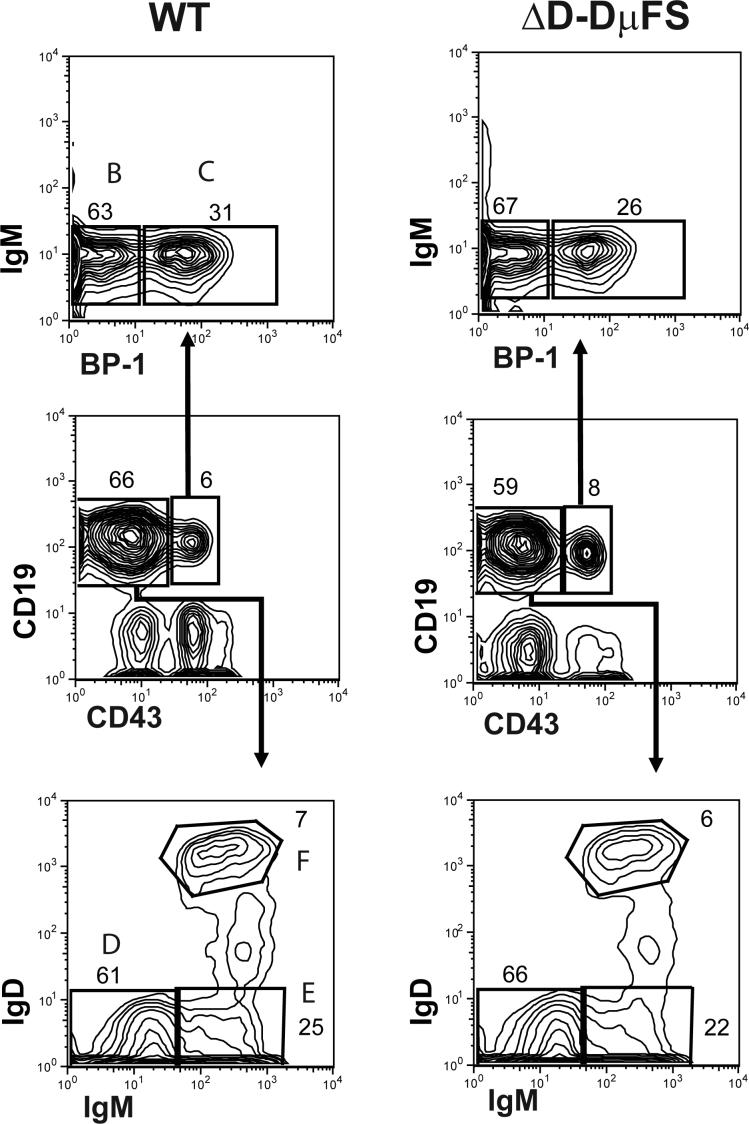

Figure 2. Flow cytometric gates for the collection of bone marrow B lineage cells from homozygous ΔD-DμFS and wild-type (WT) littermates.

Cells within the lymphocyte gate were first distinguished on the basis of the expression of CD19 and CD43. Early B-cell progenitors (CD19+ CD43+) were divided into fractions B and C on the basis of the expression of BP-1. Late pre-B, immature B, and mature B cells (CD19+ CD43−) were divided into fractions D, E and F on the basis of the surface expression of IgM and IgD.

RNA, RT-PCR, cloning, sequencing, and sequence analysis

Total RNA isolation, VH7183-specific VDJCμ RT-PCR amplification, cloning, sequencing, and sequence analysis was performed as previously described (12,14,15). The sequences reported in this paper have been placed in the GenBank database (accession numbers EF627050-EF627448). A listing of the distribution by developmental stage of the 1355 wild type, 235 ΔD-DμFS, 243 ΔD-DFL, and 342 ΔD-iD sequences used for analysis in the work is provided in Supplemental Table S1. The CDR-H3 sequences obtained from the ΔD-DμFS mice and their wild-type littermate controls are presented in disassembled form in an accompanying Microsoft Excel file labeled Supplemental Compilation of CDR-H3 Sequences.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with JMP version 7.0 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) as previously described (12,14,15). Means are accompanied by the standard error of the mean.

Results

Frame shifting the Dμ ATG start site and the DH-JH microhomology region transfers the reading frame bias of DFL16.1 from RF1 to RF2

To test the role of DH sequence in the regulation of reading frame usage, we introduced two frameshift mutations into the sequence of DFL16.1. By inserting a thymine (T) at the 5’ terminus of DFL16.1, the first mutation shifted the Dμ ATG start site from RF2 to RF1 (Figure 1, Frameshift #1). By inserting a thymine six bases upstream of the 3’ terminus of DFL16.1, the second mutation shifted the region of DH-JH microhomology from RF1 to RF2 (Figure 1, Frameshift #2). This second mutation also shifted the distal RF3-encoded TAG termination codon from RF3 to RF1. We termed the resulting DH mutant DμFS, for Dμ frameshift (21).

To introduce the DμFS allele into the BALB/c genome, we modified an existing DFL16.1 loxP-neo-loxP construct (14,15) to encode DμFS in place of wild type DFL16.1. We introduced DμFS into the DFL16.1 locus of a BALB/c embryonic stem cell that had previously undergone cre-loxP mediated removal of JH-proximal DQ52 (22). In order to delete (ΔD) the intervening eleven DH and the neo-loxP cassette, we bred a heterozygous BALB/c DμFS male mouse to a BALB/c cre expressing female. The offspring whose DH locus had undergone deletion between the DFL16.1-proximal and the JH-proximal loxP sites retained only DμFS in this new ΔD-DμFS IgHa allele. We bred this new mutant DH to homozygosity.

To test whether these DH frameshift mutations would alter RF preference early in B cell development, we used the scheme of Hardy (23) to identify B cell progenitors from the bone marrow of homozygous BALB/c ΔD-DμFS mice. We RT-PCR cloned VH7183-D-J-Cμ transcripts from fraction B (CD19+CD43+BP-1−IgM− pro-B cells) (Figure 2), a stage prior to that associated with cell surface expression of Igμ. In these and other experiments, we compared the results obtained from sequencing VH7183-D-J-Cμ transcripts from ΔD-DμFS mice to that of similar transcripts from both wild-type and homozygous ΔD-DFL BALB/c mice. The latter are restricted to use of only DFL16.1 in their DH locus (15). When compared to ΔD-DFL and wild-type mice, the ratio of DFL16.1 RF1 to RF2 usage was reversed (Figure 3).

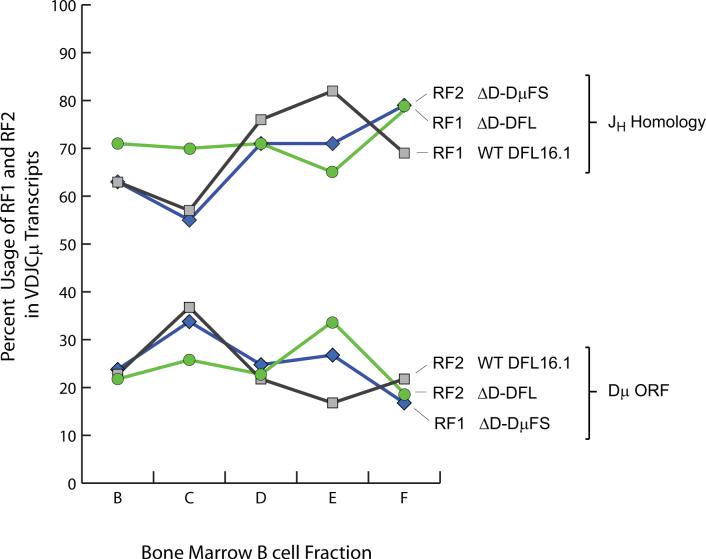

Figure 3. The two DH frameshift mutations flip the usage ratio of RF1 versus RF2.

The percent usage of RF1 and RF2 among unique, in-frame Igμ transcripts with recognizable DFL16.1 sequence from Hardy fractions B (CD19+ CD43+ IgM− BP-1−), C (CD19+ CD43+ IgM− BP-1+), D (CD19+ CD43− IgM− IgD−), E (CD19+ CD43− IgM+ IgD−), and F (CD19+ CD43− IgMlo IgDhi) from wild type, ΔD-DFL, and ΔD-DμFS mice is displayed. When compared to ΔD-DFL and wild type controls, the use of hydrophobic and neutral DH reading frames has been flipped in B lineage cells from ΔD-DμFS mice.

The frequency of RF3, which retained its central termination codon, did not change. Thus we found no in vivo evidence that the elimination of a terminal stop codon in RF3, or the introduction of a terminal stop codon to RF1, would affect the prevalence of RF3-containing CDR-H3s among Igμ sequences with open reading frames.

Given that the distal TAG from RF3 now served as the penultimate codon for RF1 (Figure 1), we calculated that an exonucleolytic loss of at least five nucleotides at the 3’ terminus of the DμFS gene segment would be required to permit formation of an open reading frame (ORF) in RF1-containing transcripts. Unsurprisingly, on average fraction B DμFS RF1–containing ORF transcripts lost eight 3’ nucleotides; whereas the average 3’ loss in RF2-containing ORFs was only four (p < 0.001).

Enhanced use of RF2 yields a hydrophobic CDR-H3 repertoire enriched for valine

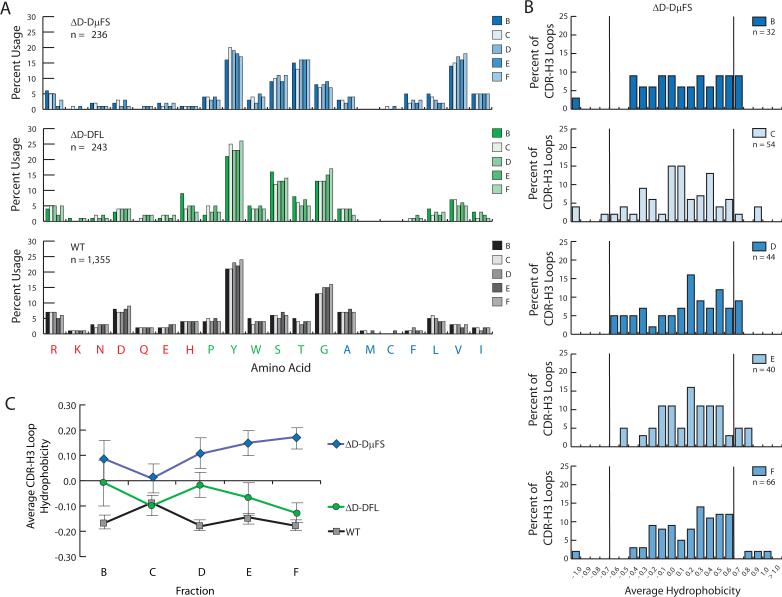

The new bias for use of RF2 among the B cell progenitors in fraction B from the ΔD-DμFS mice translated into a globally altered polyclonal CDR-H3 repertoire enriched for RF2-encoded hydrophobic amino acids (Figure 4). In particular, translation resulted in enrichment for RF2-encoded valine with a corresponding depletion of RF1-encoded tyrosine and glycine.

Figure 4. Amino acid usage and average hydrophobicity profiles for CDR-H3 sequences from ΔD-DμFS, ΔD-DFL, and wild type B lineage cells from progressive stages of B cell development.

(A) Distribution of individual amino acids in the CDR-H3 loop of sequences from homozygous ΔD-DμFS, ΔD-DFL, and wild-type (WT) mice as a function of bone marrow B cell development. The Hardy bone marrow B lineage designation of fractions B through F (23) was used throughout. (B) Distribution of average CDR-H3 hydrophobicities in VH7183DJCμ transcripts from homozygous ΔD-DμFS mice as a function of bone marrow B cell development. The normalized Kyte-Doolittle hydrophobicity scale (34) has been used to calculate average hydrophobicity. Although this scale ranges from −1.3 to + 1.7, only the range from −1.0 (charged) to +1.0 (hydrophobic) is shown. Prevalence is reported as the percent of the sequenced population of unique, in-frame, open transcripts from each B lineage fraction. To facilitate visualization of the change in variance of the distribution, the vertical lines mark the preferred range average hydrophobicity previously observed in wild-type fraction F (12). (C) Average CDR-H3 hydrophobicity of the VH7183DJCμ transcripts from homozygous ΔD-DμFS, ΔD-DFL, and wild-type mice as a function of bone marrow B cell development. The standard error of the mean is shown. In the ΔD-DμFS mice, the change in average hydrophobicity from fraction C to fraction F was significant at p<0.03.

Terminal DH-JH microhomology appears to play a limited role in controlling DH reading frame preference in ΔD-DμFS mice

The role of DH-JH microhomology would be predicted to be most apparent among rearrangements that lack N nucleotides at the D→J junction, especially among those with a demonstrable overlap in D/J sequence. The number of sequences from fraction B that fit these descriptions was insufficient to allow meaningful analysis. However, in order to pursue our studies of the role of the DH in repertoire development, we also obtained CDR-H3 sequences from in-frame VH7183-D-J-Cμ transcripts from fraction C (CD19+CD43+BP-1+IgM− early pre-B cells), fraction D (CD19+CD43−IgM−IgD− late pre-B cells), fraction E (CD19+CD43−IgM+IgD− immature B cells), and fraction F (CD19+CD43−IgM+IgD+ mature, recirculating B cells) (Figure 2). We grouped all of the sequences that we obtained and then examined the pattern of RF1 among those lacking nucleotides between DH and JH , with a special focus on those sequences with evidence of one or more nucleotides of D/J overlap. We compared the results obtained in the ΔD-DμFS mice to the ΔD-DFL control, which, because it also contained only one DH, also allowed identification of N nucleotides with certainty.

As predicted, among the ΔD-DFL sequences the frequency of rearrangement into RF1 was greater among those DJ joins that lacked N nucleotides (49 of 60 [82%]) than among the DJ joins that contained them (111 of 164 [68%], p < 0.05). Unexpectedly, the same did not hold true for ΔD-DμFS. RF2 usage was nearly identical between those sequences that lacked N nucleotides (31 of 44 [70%]) and those that contained them (112 of 165 [68%]; p=0.74). This same trend was evident at all stages of B cell development examined, although the numbers were too small to reach statistical significance for each individual stage.

Closer inspection revealed an even greater shift in reading frame usage among the ΔD-DμFS sequences with direct D/J overlap, with only half (8 of 16) using RF2, versus 93% of the ΔD-DFL sequences using RF1 (28 of 30, p<0.002). This reflected an altered pattern of the site of rearrangement at the 3’ terminus of the D. Whereas the average loss of 3’ nucleotides in DFL16.1 sequences among the wild-type and ΔD-DFL sequences that contained D/J overlap was statistically indistinguishable (0.8 ± 1.3 and 1.9 ± 0.7, respectively; p=0.45), the average DμFS sequence containing D/J overlap was more than twice that (4.8 ± 1.0, p<0.03 for both controls). Thus a frameshift in the midst of the coding sequence of the DH altered the behavior of the rearrangement process.

No major evidence of selection for use of RF1 or for RF1-encoded amino acids

To test whether B cell maturation, which is dependent in part on successful testing of the antigen-binding properties of the B cell receptor, would be associated with selection for that minority of developing B cells which had rearranged their DH in RF1, we evaluated RF usage among in-frame VH7183-D-J-Cμ transcripts obtained at random from fraction C through fraction F bone marrow B lineage cells (Figure 2). Not only did we fail to find enrichment for RF1 with development, we actually observed enrichment for RF2 (Figure 3). The increase in the use of RF2 with B cell maturity matched that observed for RF1 among both ΔD-DFL and wild type controls.

To test whether B cell maturation would be associated with selection for tyrosine and glycine, which are normally preferred, we examined global amino acid content in the CDR-H3 loop sequences from fraction C to F. The new bias for RF2 encoded hydrophobic amino acids persisted with development up to and including fraction F (Figure 4A), persistently skewing the distribution of average CDR-H3 hydrophobicity in this recirculating, mature B cell population toward the hydrophobic end of the spectrum (Figure 4B). In particular, we found no evidence of selection for RF2-containing CDR-H3s that had gained tyrosine or glycine by means of N region addition coupled with exonucleolytic loss of terminal DH sequence.

In wild-type mice, sequences with an average hydrophobicity greater than +0.60 or less than −0.70 are progressively culled from the repertoire during B cell development (12,13). Among those sequences obtained from ΔD-DμFS fraction F B cells, several exhibited CDR-H3s with an average hydrophobicity greater than +0.60 (Figure 4B). Coupled with a failure to enrich for sequences within the normally preferred hydrophobic range of > −0.40 and ≤ 0.00, the presence of these hydrophobic sequences led to an increase in average CDR-H3 loop hydrophobicity with development (p = 0.03, fraction C versus fraction F; Figure 4C).

[A complete listing of the nucleotide and predicted amino acid sequences of the ΔD-DμFS CDR-H3s reported in this manuscript can be found in the accompanying supplemental Microsoft Excel® file. ]

No major changes in VH and JH usage

To test whether the shift in CDR-H3 hydrophobicity might be ‘tempered’ by a compensatory change in VH or JH usage, we compared VH7183 and JH usage in the ΔD-DμFS B lineage cells to controls. The pattern of use of VH7183 gene segments proved statistically indistinguishable from the controls (12,14,15) (Figure 5). When compared to wild type, the use of JH4 was diminished and use of JH1 enhanced among ΔD-DμFS containing transcripts (Figure 5). This pattern matched that observed in the CDR-H3 repertoires of the two previous single DH mice (14,15) and likely reflects the elimination of the rest of the DH locus, including DQ52 (22).

Figure 5. VH 7183 and JH gene segment usage during bone marrow B cell development in homozygous ΔD-DμFS, ΔD-DFL, and wild-type (WT) mice.

VH 7183 and JH usage is reported as the percent of the sequenced population of unique, in-frame, open transcripts for Hardy fractions B (left) through F (right) (23). The VH and JH gene segments are arranged in germline order. (Top) VH 7183 and JH use in homozygous ΔD-DμFS mice. (Middle) VH 7183 and JH use in homozygous ΔD-DFL mice. (Bottom) VH 7183 and JH use in wild type, homozygous BALB/c mice.

Each DH reading frame appears to generate its own characteristic global amino acid repertoire

To further test for evidence of selection for or against specific patterns of amino acid usage of the global CDR-H3 repertoire, we compared CDR-H3 composition by reading frame. The numbers of sequences were insufficient to allow meaningful analysis by developmental stage. However, given that the overall pattern of amino acid content appeared relatively stable (Figure 4A) (15), we reasoned that comparing RF1 versus RF2 sequences regardless of developmental stage would be appropriate. We found that the ΔD-DμFS RF2 repertoire generally matched that generated by DFL16.1 RF2 in both wild-type and ΔD-DFL mice (data not shown). Similarly, RF1 in the ΔD-DμFS mice generated a neutral CDR-H3 loop repertoire with a pattern of amino acid usage similar to that obtained from the RF1-generated repertoire from controls.

Selection for length and DH content among DμFS CDR-H3 sequences that use RF1

In both mouse and human, a selection for a specific range and average of CDR-H3 lengths is consistently observed during B cell development (12,13,24). As noted above, making TAG (Figure 1) the penultimate 3’ codon of DμFS RF1 would require that this mutant DH undergo a minimum loss of five nucleotides in order to produce a functional V domain. This was borne out in practice, with productive in-frame VH7183-D-J-Cμ transcripts from ΔD-DμFS fraction B cells losing an average of eight 3’ terminal nucleotides versus an average loss of only four 3’ terminal nucleotides among DFL16.1-containing transcripts from the controls (p <0.001) (Figure 6A). Because the extent of 5’ loss among the ΔD-DμFS fraction B cells was statistically indistinguishable from controls (Figure 6B), the increased loss of 3’ nucleotides led to ΔD-DμFS RF1 contributing, on average, approximately four fewer germ line encoded nucleotides to CDR-H3 than controls (p<0.05)(Figure 6C). As a result, the average length of CDR-H3 in fraction B was almost one codon shorter than controls (Figure 6D).

Figure 6. Mutant and wild type DFL16.1 terminal modification during B lineage development in bone marrow.

Shown is the average loss of 3’ (Figure 7A) and 5’ (Figure 7B) nucleotides from the termini of mutant and wild type DFL16.1 gene segments among unique, in-frame, open VH7183DJCμ transcripts from Hardy fractions B through F. With maturation, there is increased preservation of both 3’ and 5’ terminal nucleotides among the transcripts which contain the DμFS gene segment. This achieves near identity in the contribution of germline-encoded DH nucleotides to the mature B cell CDR-H3 repertoire (Figure 7C), as well as near identity in the average length of CDR-H3 (Figure 7D) from ΔD-DμFS B cells and the ΔD-DFL and wild-type (WT) controls. The standard error of the mean is shown. Statistical analyses were focused on a comparison between ΔD-DμFS and ΔD-DFL, both of which are limited to use of a single DFL16.1 gene segment. Statistical significance is marked by * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, and *** p<0.001.

With development, however, the contribution of germline DH sequence increased. This effect was most notable among B cells from fraction F, where the average loss of 3’ nucleotides had dropped from eight to seven; and, more importantly, where the average loss of 5’ nucleotides dropped precipitously from six to two (p <0.05). The effect was to create a mature ΔD-DμFS RF1 repertoire that maintained the same relative contribution of germline DH sequence as wild-type DFL16.1 RF1 in CDR-H3 intervals of the same average length. Although the numbers were insufficient to perform a statistical analysis of global amino acid content, in general the effect of the change in nucleotide loss would be to compensate for the loss of 3’ tyrosine with a 5’ tyrosine encoded by the 5’ terminus of the DH (Figure 1). Thus, while the absolute sequence of the RF1-encoded CDR3-centric antigen binding site repertoire was not being recreated, the global amino acid composition of the repertoire in mature B cells was more likely to match that of wild type controls.

Discussion

Although DH gene segments were named for their role in increasing the potential for diversity at the time of immunoglobulin rearrangement, i.e. D-diversity, they conserve in their sequence a number of molecular properties that have been proposed to regulate both choice of reading frame and the amino acid content of CDR-H3, which forms the center of the classic antigen binding site (10,20). In the present work, we have taken a genetic approach to directly test the role of several of these molecular properties in regulating RF usage and CDR-H3 content.

By inserting two thymines in the coding sequence of DFL16.1, the first six nucleotides from the 3’ terminus and the second at the 5’ terminus, we altered the three molecular properties that have been associated with control of reading frame preference in DFL16.1, the most commonly used DH gene segment in BALB/c mice. Inspection of compilations of recombination sequence signal (RSS) elements has shown that the ‘nonconserved spacer’ sequence between the heptamer and nonamer can be conserved within groups of evolutionarily-related sequences (25), and that the sequences flanking the RSS heptamer and nonamer, including the spacer and the adjacent coding sequence, can influence patterns of rearrangement (26-28). In our case, the mutations we created maintained the germline sequence and context of the RSS and adjacent nucleotides.

A number of previous studies have provided strong support for the role of terminal D/J microhomology in biasing reading frame preference (9,18,29). We designed the 3’ insertion to shift the region of terminal DH RF1-JH microhomology to RF2. Because the sequence of the JH locus remained unchanged, the putative ability of the region of DH-JH microhomology to contribute to the coding sequence of CDR-H3 was maintained. However, shifting the six terminal 3’ nucleotides of DFL16.1 from RF1 to RF2 appeared to have a minimal effect on RF2 reading frame usage in the developing repertoire. Given that the rest of the adjacent sequence of DFL16.1 was maintained in germ line content and that the actual site of rearrangement in sequences with demonstrable D/J overlap changed as a result of the frameshift, it remains possible that the coding sequence adjacent to the region of terminal homology also exerts an effect on processing of the terminal end of the DH during D→J rearrangement and thus on reading frame bias. This effect would necessarily be separate from the direct role of terminal D/J microhomology.

RF3 in DFL16.1 normally contains two TAG termination codons (Figure 1). The insertion of thymine 7 base pairs for the 3’ end of the coding sequence moved the distal TAG termination codon from RF3 to RF1. We hypothesized that the inclusion of a termination codon in RF1 would lead to a further decrease in its use in the functional repertoire due to the decreased likelihood of creating open reading frames. We further assumed that the loss of a termination codon in RF3 would lead to an increase in its representation in the functional repertoire. However the prevalence of the modified RF3, which retained its first, central termination codon, remained unchanged. And the prevalence of ΔD-DμFS RF1, which now encodes a TAG as its penultimate codon, matched that observed in RF2 in both the wild-type and ΔD-DFL controls. This suggests that the relative position of the termination codon in a DH RF may be critical to its ability to limit use of that RF.

The 5’ insertion shifted the upstream Dμ ATG start site from RF2 to RF1. Previous studies have shown that disruption of the Cμ membrane terminus leads to random representation of DH reading frames (20). These experiments linked expression of the membrane form of Dμ protein with inhibition of V→DJ joining and provided initial evidence that the bias in DH usage was the product of repertoire selection on an evolutionary scale. Subsequent studies in mice unable to express the surrogate light chain molecule λ5 (30) provided further support for the hypothesis that selection against RF2 occurred primarily in pre-B cells by engaging the process of allelic exclusion.

Our studies now show that moving the RF1 coding sequence in-frame with the Dμ ATG start site increased the representation of DFL16.1 RF2 among the CDR-H3 repertoire in progenitor B cells to that normally observed for RF1, and vice versa. Thus, of the three mechanisms postulated to regulate RF usage that we tested, the negative effect of a Dμ open reading frame appeared to dominate, further confirming the key role of Dμ protein expression in regulating DH reading frame preference in mice.

Preservation of the pattern of amino acid representation by reading frame is a major conserved feature of diversity gene segments (10). In previous studies we have shown that we could completely alter the general amino acid composition of the CDR-H3 repertoire expressed by progenitor B cells by inverting the coding sequence of the DH (14). These studies also showed that the forces of selection which operate during passage of the developing B cell population through the checkpoints necessary to achieve maturity could not return the CDR-H3 repertoire to that normally found in wild type mice. These findings provided strong support for the view that the sequence of the DH, which is subject to natural selection, plays a key role in regulating, or delimiting, the composition of CDR-H3. The extent of that role, however, remained uncertain.

For mice bearing the ΔD-iD mutation (14), recreation of a more wild type tyrosine and glycine enriched repertoire would have required selection for rare sequences that either contained a DH gene segment that had undergone inversion or that had undergone extensive exonucleolytic loss coupled with just the right combination of N nucleotides to recreate a tyrosine-glycine enriched sequence. In contrast, for mice bearing the ΔD-DμFS mutation one-fifth of the transcripts in the progenitor B cell population were already using the normally preferred RF1. This should have lowered the threshold for detection of somatic selection during development for tyrosine and glycine enriched CDR3-centric antigen binding sites.

Examination of the repertoire expressed by pre-B cells, immature B cells, and mature B cells revealed that the switch from RF1 to RF2 dictated to progenitor cells by the altered molecular properties of the mutated DH persisted as the developing B cells passed through subsequent developmental checkpoints even though this created a global shift in CDR-H3 amino acid content. We found no evidence for selection of RF2 rearrangements that had undergone enhanced N addition or increased exonucleolytic loss of DH sequence, either of which could have reduced use of valine or increased the contribution of tyrosine and glycine in sequences that used RF2. Finally, there was no demonstrable change in VH or JH usage other than that imposed by the reduction in available DH elements. Together these findings underscore the critical role of germline DH sequence in preselecting the diversity of the pre-immune CDR-H3 repertoire.

Although the results of this study support a dominant role for germline DH sequence in delimiting the general global amino acid content of the CDR-H3 repertoire, closer inspection revealed a subtle, but significant, effect of selection for a specific range of germline encoded CDR-H3s into the mature, recirculating B cell pool. In spite of the forced loss of two terminal codons, the DFL16.1 RF1-containing CDR-H3 repertoire in mature, recirculating B cells was observed to match the extent of germline DH nucleotide contribution and CDR-H3 length found in both the wild type and ΔD-DFL controls. The finding that there is somatic selection among the 20% of sequences that use DμFS in RF1 but not among the 60% of sequences that use DμFS in RF2 suggests separate regulation by reading frame of CDR-H3 content. This would suggest that exposure to common antigens in the periphery selects for a specific range of DFL16.1 RF1-encoding CDR-H3s.

In previous studies we have shown that mice forced to express an antibody repertoire depleted of CDR-H3 tyrosine and glycine, but enriched for arginine and other charged amino acids, demonstrate reductions in B cell and antibody production as well as increased susceptibility to infection with a common pathogenic virus (14,31). In a related series of studies, we have found that enrichment for RF2-encoded valine-enriched CDR-H3s can also degrade B cell development and antigen-specific antibody production (32), even when a significant minority of B cells continues to produce a tyrosine and glycine-enriched CDR-H3 repertoire. This would suggest that failure to properly maintain the correct balance of amino acids within the CDR-H3 repertoire as a result of chance, age, or an inherited tendency could alter immune function in otherwise healthy patients, potentially influencing susceptibility to disease. These data also support the view that the evolution of D gene sequence may reflect a balance between the need to avoid the D-disaster (6) that can occur with use of disfavored DH sequence and the need to maintain the D-diversity necessary to create an effective adaptive immune response.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank P. Burrows, M. Cooper, J. Kearney, and Rolf F. Maier for their invaluable advice and support.

Abbreviations

- ΔD-DFL

depleted DH locus with a single DFL16.1 gene segment

- ΔD-iD

depleted DH locus with a single, mutated DFL16.1 gene segment containing inverted DSP 2.2 sequence

- ΔD-DμFS

depleted DH locus with a single, frameshifted DFL16.1 gene segment

- CDR-H3

immunoglobulin heavy chain complementarity determining region 3

- RF

DH reading frame

- iRF

inverted DH reading frame

- RSS

recombination signal sequence

REFERENCES

- 1.Kabat EA, Wu TT, Perry HM, Gottesman KS, Foeller C. Sequences of proteins of immunological interest. 5 ed. U.S.Department of Health and Human Services; Bethesda, Maryland: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Padlan EA. Anatomy of the antibody molecule. Mol. Immunol. 1994;31:169–217. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(94)90001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu JL, Davis MM. Diversity in the CDR3 region of V(H) is sufficient for most antibody specificities. Immunity. 2000;13:37–45. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tonegawa S. Somatic generation of antibody diversity. Nature. 1983;302:575–581. doi: 10.1038/302575a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alt FW, Baltimore D. Joining of immunoglobulin heavy chain gene segments: Implications from a chromosome with evidence of three D-J heavy fusions. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. ,U. S. A. 1982;79:4118–4122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.13.4118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohn M. A hypothesis accounting for the paradoxical expression of the D gene segment in the BCR and the TCR. Eur. J. Immunol. 2008;38:1179–1187. doi: 10.1002/eji.200738089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feeney AJ, Clarke SH, Mosier DE. Specific H chain junctional diversity may be required for non- T15 antibodies to bind phosphorylcholine. J. Immunol. 1988;141:1267–1272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ichihara Y, Hayashida H, Miyazawa S, Kurosawa Y. Only DFL16, DSP2, and DQ52 gene families exist in mouse immunoglobulin heavy chain diversity gene loci, of which DFL16 and DSP2 originate from the same primordial DH gene. Eur. J. Immunol. 1989;19:1849–1854. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830191014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gu H, Forster I, Rajewsky K. Sequence homologies, N sequence insertion and JH gene utilization in VH-D-JH joining: implications for the joining mechanism and the ontogenetic timing of Ly1 B cell and B-CLL progenitor generation. EMBO J. 1990;9:2133–2140. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07382.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ivanov II, Link JM, Ippolito GC, Schroeder HW., Jr. Constraints on hydropathicity and sequence composition of HCDR3 are conserved across evolution. In: Zanetti M, Capra JD, editors. The Antibodies. Taylor and Francis Group; London: 2002. pp. 43–67. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schroeder HW, Jr., Ippolito GC, Shiokawa S. Regulation of the antibody repertoire through control of HCDR3 diversity. Vaccine. 1998;16:1383–1390. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00096-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ivanov II, Schelonka RL, Zhuang Y, Gartland GL, Zemlin M, Schroeder HW., Jr. Development of the expressed immunoglobulin CDR-H3 repertoire is marked by focusing of constraints in length, amino acid utilization, and charge that are first established in early B cell progenitors. J. Immunol. 2005;174:7773–7780. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.12.7773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schelonka RL, Tanner J, Zhuang Y, Gartland GL, Zemlin M, Schroeder HW., Jr. Categorical selection of the antibody repertoire in splenic B cells. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Ippolito GC, Schelonka RL, Zemlin M, Ivanov II, Kobayashi R, Zemlin C, Gartland GL, Nitschke L, Pelkonen J, Fujihashi K, Rajewsky K, Schroeder HW., Jr. Forced usage of positively charged amino acids in immunoglobulin CDR-H3 impairs B cell development and antibody production. J. Exp. Med. 2006;203:1567–1578. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schelonka RL, Ivanov II, Jung D, Ippolito GC, Nitschke L, Zhuang Y, Gartland GL, Pelkonen J, Alt FW, Rajewsky K, Schroeder HW., Jr. A single DH gene segment is sufficient for B cell development and immune function. J. Immunol. 2005;175:6624–6632. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.10.6624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reth MG, Alt FW. Novel immunoglobulin heavy chains are produced from DJH gene segment rearrangements in lymphoid cells. Nature. 1984;312:418–423. doi: 10.1038/312418a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feeney AJ. Lack of N regions in fetal and neonatal mouse immunoglobulin V-D-J junctional sequences. J. Exp. Med. 1990;172:1377–1390. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.5.1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feeney AJ. Predominance of VH-D-JH junctions occurring at sites of short sequence homology results in limited junctional diversity in neonatal antibodies. J. Immunol. 1992;149:222–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nadel B, Feeney AJ. Influence of coding-end sequence on coding-end processing in V(D)J recombination. J. Immunol. 1995;155:4322–4329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gu H, Kitamura D, Rajewsky K. B cell development regulated by gene rearrangement: arrest of maturation by membrane-bound D mu protein and selection of DH element reading frames. Cell. 1991;65:47–54. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90406-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zemlin M, Schelonka RL, Ippolito GC, Nitschke L, Pelkonen J, Rajewsky K, Schroeder HW., Jr. Forced use of DH RF2 sequence impairs B cell development. In: Kalil J, Cunha-Neto E, Rizzo LV, editors. 13th International Congress of Immunology. Medimond International Proceedings; Bologna: 2007. pp. 507–511. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nitschke L, Kestler J, Tallone T, Pelkonen S, Pelkonen J. Deletion of the DQ52 element within the Ig heavy chain locus leads to a selective reduction in VDJ recombination and altered D gene usage. J. Immunol. 2001;166:2540–2552. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.4.2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hardy RR, Hayakawa K. B cell development pathways. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2001;19:595–621. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shiokawa S, Mortari F, Lima JO, Nunez C, Bertrand FEI, Kirkham PM, Zhu S, Dasanayake AP, Schroeder HW., Jr. IgM HCDR3 diversity is constrained by genetic and somatic mechanisms until two months after birth. J. Immunol. 1999;162:6060–6070. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schroeder HW, Jr., Hillson JL, Perlmutter RM. Structure and evolution of mammalian VH families. Int. Immunol. 1990;2:41–50. doi: 10.1093/intimm/2.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gauss GH, Lieber MR. The basis for the mechanistic bias for deletional over inversional V(D)J recombination. Genes & Development. 1992;6:1553–1561. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.8.1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bassing CH, Alt FW, Hughes MM, D'Auteuil M, Wehrly TD, Woodman BB, Gartner F, White JM, Davidson L, Sleckman BP. Recombination signal sequences restrict chromosomal V(D)J recombination beyond the 12/23 rule. Nature. 2000;405:583–586. doi: 10.1038/35014635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gerstein RM, Lieber MR. Coding end sequence can markedly affect the initiation of V(D)J recombination. Genes & Development. 1993;7:1459–1469. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.7b.1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gerstein RM, Lieber MR. Extent to which homology can constrain coding exon junctional diversity in V(D)J recombination. Nature. 1993;363:625–627. doi: 10.1038/363625a0. [published erratum appears in Nature 1993 Sep 30;365(6445):468].

- 30.Loffert D, Ehlich A, Muller W, Rajewsky K. Surrogate light chain expression is required to establish immunoglobulin heavy chain allelic exclusion during early B cell development. Immunity. 1996;4:133–144. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80678-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nguyen HH, Zemlin M, Vu HL, Ivanov II, Andrasi J, Zemlin C, Schelonka RL, Schroeder HW, Jr., Mestecky J. Heterosubtypic immunity to influenza A virus infection requires a properly diversified antibody repertoire. J. Virol. 2007;81:9331–9338. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00751-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schelonka RL, Zemlin M, Kobayashi R, Szalai A, Ippolito GC, Zhuang Y, Gartland GL, Fujihashi K, Rajewsky K, Schroeder HW., Jr. Preferential use of DH reading frame 2 alters B cell development and antigen-specific antibody production. 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Kurosawa Y, Tonegawa S. Organization, structure, and assembly of immunoglobulin heavy chain diversity DNA segments. J. Exp. Med. 1982;155:201–218. doi: 10.1084/jem.155.1.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eisenberg D. Three-dimensional structure of membrane and surface proteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1984;53:595–623. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.53.070184.003115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.