Abstract

Nitric oxide (NO) and associated reactive nitrogen species (RNS) are involved in many physiological functions. There has been an ongoing debate to whether RNS can inhibit or perpetuate chronic inflammation and associated carcinogenesis. Although the final outcome depends on the genetic make-up of its target, the surrounding microenvironment, the activity and localization of nitric oxide synthase (NOS) isoforms, and overall levels of NO/RNS, evidence is accumulating that in general, RNS drive inflammation and cancers associated with inflammation. To this end, many complementary and alternative medicines (CAMs) that work in chemoprevention associated with chronic inflammation, are inhibitors of excessive NO observed in inflammatory conditions. Here we review recent literature outlining a role of NO/RNS in chronic inflammation and cancer, and point toward NO as one of several targets for the success of CAMs in treating chronic inflammation and cancer associated with this inflammation.

Introduction

Several groups, including ourselves, have recently written reviews detailing our current knowledge of the role of NO/RNS in inflammation and carcinogenesis [1–4]. Although these reviews come to a general consensus that NO and RNS play paradoxical roles in carcinogenesis, they list the experimental studies in tabular form, which indicate approximately two out of three studies find NO potentiates inflammation and/or carcinogenesis. As also indicated in these and other reviews, final outcome depends on the experimental model, the genetic make-up of NO/RNS targets, the surrounding microenvironment, the activity and localization of NOS isoforms, and overall levels of NO/RNS. Regarding the latter issue of overall levels, although pathological levels of NO can have free radical scavenging properties, and drive apoptosis, a general finding is that these levels have pro-cancerous consequences [2], mechanistically by modifying bio-molecules such as DNA, proteins, and lipids.

The case for NO as a key modulator of inflammation and cancer

Reactive species overload diseases are associated with a high cancer risk [5]. The finding that inducible NOS (iNOS) expression is elevated in these diseases, points toward its pathological impact. Chronically elevated levels of NO/RNS leads to several chemical processes, including nitration, nitrosylation, nitrosation, and oxidation. Chemical modification of cancer proteins can ultimately drive carcinogenesis, by causing dysfunction of such proteins. DNA base deamination, the formation of exocyclic-DNA adducts, and single and double-stranded breaks in DNA can also occur, increasing the risk of somatic mutation in cancer genes.

As mentioned, either pharmacologically, or molecular targeting iNOS, endothelial NOS (eNOS), or neuronal NOS (nNOS), or all three isoforms has a preventive effect on carcinogenesis in approximately two out of three published studies. NO/RNS as an exacerbator, or inhibitor of inflammation is also paradoxical. One can interpret the high NOS expression observed in reactive species overload diseases as either being a reactive protective mechanism, or a cause of the disease.

One argument that NO is protective against chronic inflammation is the finding that NO-releasing NSAIDs are successful in treating colitis and gastritis [6,7]. Mechanistically, this may be due to the cytotoxic effect of NO on lamina propria T-helper Type 1 cells [8]. Caution should be used, here, however, when extrapolating these positive outcomes in reactive species overload diseases to cancer associated with these diseases. Although high levels of NO can drive apoptosis of inflammatory cells, this may come at the risk of mutagenesis to by-standing epithelial cells [9]. On the basis of the available published literature, overall, NO/RNS promotes de novo tumorigenesis when associated with chronic inflammation, angiogenesis and growth of established solid tumors [4].

NO is not the only target for prevention and treatment of chronic inflammation

Although iNOS is easily induced and expressed in macrophages during host-defense mechanisms, many other cell types such as endothelial and epithelial cells have been shown to express iNOS. An increased level of constitutive and inducible NOS expression and/or activity is also observed in a variety of human cancers. Moreover, iNOS expression and/or nitrotyrosine accumulation, in the mucosa of patients with reactive species overloads diseases [including ulcerative colitis (UC), Helicobacter pylori–associated gastritis, viral hepatitis, Wilson’s Disease, hemochromatosis, and Barrett’s esophagus, [1]] indicate that NO production and peroxynitrite formation may be involved in the pathogenesis of these diseases, and thus predispose individuals to cancer.

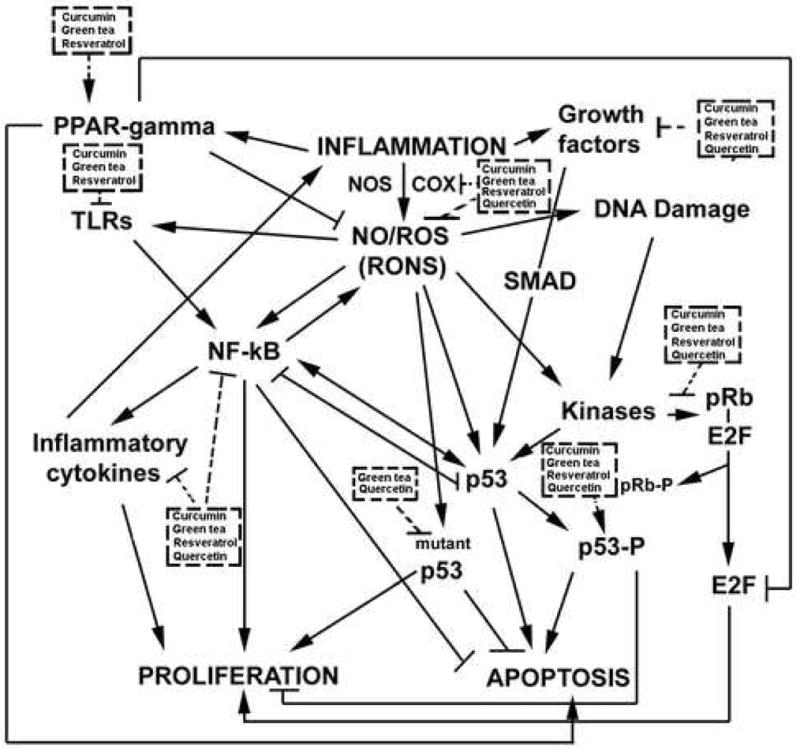

With this body of evidence, it is intriguing to speculate targeting NO will prevent and treat chronic inflammation and cancers associated with chronic inflammation. This, however, does not take into account the complexity of the inflammatory micro-environment, and the plethora of molecules shown to play a key role in these diseases. We have recently reviewed these players [5,10]. Briefly, in addition to NO and nitric oxide synthases, these molecules include nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB); toll-like receptors (TLRs); reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS); cyclooxygenases (COXs); pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines; metals; antioxidant enzymes; peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) ligands; kinases; growth factors; and the tumor suppressor proteins, p53 and retinoblastoma (pRb) (Figure 1). All are potential targets for the prevention and treatment of chronic inflammation, cancer chemoprevention and cancer treatment.

Fig. 1.

Popular and powerful CAMs target many key players in inflammation.

Agents that target individual or multiple players in this cascade have been used with success in humans. These include the use of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF- α) inhibitors (monoclonal antibodies) for Crohn’s disease and UC [11,12] and interferon-α (IFN-α) for hepatitis [13]. Some agents that target multiple players simultaneously have consistently been found to inhibit many diseases associated with chronic inflammation (cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes). These include non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, such as acetylsalicylic acid. A derivative, 5-acetylsalicylic acid (5-ASA), has been used with remarkable success in ameliorating mild to moderate bouts of inflammatory bowel disease [14]. The mechanisms of 5-ASA are not fully understood, but it inhibits COX-1 and COX-2 weakly, activates apoptosis, inhibits proliferation and NF-κB, scavenges RONS, and inhibits RON-associated base damage. Recently, it has been shown that simultaneous inhibition of COX-2 and iNOS protects from colitis in rats [15].

Research over the last few years has implicated NF-κB as a molecular node in the inflammation to cancer sequence. In un-stimulated conditions, NF-κB proteins bind to IκB. Upon stimulation, IκB proteins are phosphorylated and degraded through the proteasome. This releases NF-κB which then translocates to the nucleus and binds to its promoter elements (κB sites) and regulates the expression of many genes. Because (i) NF-κB is upregulated in reactive species overload diseases, and (ii) many of the genes targeted by NF-κB are involved in the inflammatory cascade (iNOS, COX-2, cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases), anti-apoptotic events (e.g. the pro-survival Bcl-2 homolog Bfl-1/A1) and cell cycle events (e.g. cyclin D1), it is emerging as one of the more promising targets in the chemoprevention of these diseases.

NF-κB is a target of many antioxidants associated with chemoprevention (e.g. NSAIDs, butyrate, curcumin, triterpenoids, gliotoxin and other sponge compounds, black tea, leptons, caffeic acid, resveratrol, quercetin, green tea). Therefore, its usefulness in taming high cancer risk, reactive species overload diseases has been shown indirectly. More direct genetic and pharmacological inhibition of the NF-κB pathway has been shown to inhibit experimental colitis [16,17]. Recent studies have shown NOD2 mutations - those that play a key role in Crohn’s disease - can lead to NF-κB activation [18]. This group also showed that the genetic deletion of a functional NF-κB pathway in epithelial cells protected from tumorigenesis associated with experimental colitis [16]. Deletion of functional NF-κB pathway in myeloid cells resulted in diminished activation (and thus propagation of inflammation) and reduced tumor size, indicating a protection from inflammatory-driven tumor progression. NF-κB inhibition has also been shown to protect from pancreatitis, cystitis and hepatitis progression to liver cancer (reviewed in: [5]). However, as others have pointed out [19], due to its importance in immune function, targeting NF-κB specifically for cancer chemoprevention might be impractical. To this end, targeting NF-κB for moderate inhibition in people with hyperactive immune systems (autoimmune diseases and high cancer risk reactive species overload diseases), while simultaneously targeting other key players in the inflammatory cascade (including NO), may have diverse and beneficial effects for chemoprevention. Overall, many of the CAMs showing promise in chemoprevention of high cancer risk, reactive species overload diseases, do just this.

Dietary CAMs target NO, and other players in inflammation

CAMs are a diverse group of health care practices and products that are not presently considered to be part of conventional medicine. One form of CAM is the use of natural food and herbal products to prevent and treat disease, and/or to maintain health. Although many of these products have been used for hundreds and even thousands of years, only recently have Western societies begun to appreciate the impact on human health and gain significant knowledge into their mechanism of action. As discussed, one reason for the successful use of CAMs to prevent and treat chronic inflammatory diseases is that they target key players in inflammation, including NO.

According to the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM): “the CAM domain of biologically based practices includes, but is not limited to, botanicals, animal-derived extracts, vitamins, minerals, fatty acids, amino acids, proteins, prebiotics and probiotics [live bacteria (and sometimes yeasts) found in foods such as yogurt or in dietary supplements], whole diets, and functional foods”. This is clearly a large and diverse group, and covering the impact of each on disease prevention/treatment, and their mechanism of action is beyond the scope of this review. For purposes of the present discussion, we will focus on CAMs that have been used successfully on reactive species overload diseases (animal models and/or human), then explore the mechanism by which these CAMs work. Collectively, I hope to convince you that current evidence points toward their ability to work as anti-oxidants and target key players in inflammation. This includes, but is not exclusive to, NO and RNS.

Table 1 provides and overview of some CAMs that have been used successfully to prevent and/or treat reactive species overload diseases in animals and/or humans. A scan of the literature indicates many of these compounds target the players in chronic inflammation and the inflammation-to-cancer sequence. For example (there are many), aloe vera suppresses the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines from inflammatory cells [20]. Butyrate suppresses NF-kB activation [21]. There are many more published studies showing that the listed CAMs in Table 1 target key molecules in inflammation and the inflammation-to-cancer sequence. However, this review has a focus on NO and its pathway. We have reasoned that this pathway is key to chronic inflammation, but targeting this pathway alone (as with many molecules, including NF-κB) gives paradoxical results. Therefore, although we cite studies showing an effect of various CAMs on the NO pathway, in many cases these CAMs also diminish the activation of other pro-inflammatory molecules, or stimulate the activation of anti-inflammatory molecules. We submit that such ubiquitous effects that diminish the activation and/or expression of multiple pro-inflammatory players, but do not completely block individual players (or over-stimulate anti-inflammatory players) are key to the penultimate success of certain CAMs in the prevention and treatment of autoimmune and reactive species overload diseases.

Table 1.

CAMs that protect against reactive species overload diseases

| Compound(s) | Reference | |

|---|---|---|

| Colitis | Aloe vera + ubiquinol | [154] |

| Antidepressants (desipramine) | [155] | |

| Berberine chloride | [156] | |

| * Butyrate | [157–159] | |

| Caffeic acid phenethyl ester | [160] | |

| Catalposide | [161] | |

| Cladosiphon okamuranus Tokida | [162] | |

| Cloricromene | [163] | |

| * Curcumin | [164–171] | |

| DA-9601 (standardized extract of Artemisia asiatica) | [172] | |

| * DA-6034 (a flavonoid derivative) | [173] | |

| Diammonium Glycyrrhizinate | [174] | |

| Fructo-oligosaccharide | [175] | |

| * Galanin | [176,177] | |

| * Garlic | [178–180] | |

| Ginkgo biloba | [181,182] | |

| Ghrelin | [183] | |

| Gliotoxin | [184] | |

| Glutamine | [185] | |

| Goat milk Oligosaccharides | [186] | |

| * Green tea catechins | [187–191] | |

| IDS 30 (stinging nettle extract) | [192] | |

| * Inositol compounds | [193,194] | |

| Iron chelators | [195] | |

| * Lactoferrin | [196–198] | |

| Lactulose | [199] | |

| Leptin | [200] | |

| * Linoleic acid | [201–203] | |

| Low-alkaloid tobacco | [204] | |

| * Lycopene | [200,205] | |

| Lysed E. coli | [206] | |

| Morin | [207] | |

| Nicotine | [208] | |

| Nanocrystalline silver | [209] | |

| * Omega-3 fatty acids | [210] [199,211–214] |

|

| Paeonol | [215] | |

| * Probiotics | [216–218] | |

| * (Bifidobacterium lactis, * Lactobacillus casei, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus reuteri, Lactobacillus fermentum, Lactobacillus plantarum 299V and Lactobacillus salivarius Ls-33) | [219–221] [222] |

|

| * Quercetin | [167,169,223] | |

| Quercitrin | [224] | |

| * Resveratrol | [183,225–228] | |

| * Rutoside | [167,229] | |

| Saccharomyces boulardii | [230] | |

| * Selenium | [231,232] | |

| Short chain fructooligosaccharides | [233] | |

| Sodium ferulate | [234] | |

| Thearubigin (* black tea extract) | [235–237] | |

| Traditional chinese medicines** | [238] | |

| Trimetazidine | [239] | |

| UR-1505 | [240] | |

| * Ursodiol | [241–243] | |

| * Vitamin A | [244,245] | |

| Vitamin C | [246] | |

| * Vitamin D | [247] | |

| * Vitamin E | [231,248] | |

| WR-2721 | [249] | |

| Zerumbone | [250] | |

| Zink | [251] | |

| Hepatitis | Acanthopanax senticosus | [252] |

| Cadmium | [253] | |

| Caffeic acid | [254] | |

| Cannabinoid derivative | [255] | |

| * Copper chelators | [256,257] | |

| * Curcumin | [258–260] | |

| DA-9601 | [261] | |

| DL-alpha-lipoic acid | [262] | |

| * Green tea catechins | [263,264] | |

| * Garlic | [265,266] | |

| Ginkgo biloba | [267] | |

| Ginseng | [268] | |

| * Glycyrrhizin (from liquorice root) | [269–272] | |

| Hepcidin | [273] | |

| Indigofera tinctoria Linn | [274] | |

| Iron chelators | [275] | |

| * Kampo medicines | [276,277] | |

| Kangxian baogan decoction | [278] | |

| * Lactoferrin | [197,279] | |

| Lithospermate B | [280] | |

| S-adenosylmethionine | [281] | |

| Punicalagin and punicalin | [282] | |

| * Phyllanthus | [283–286] | |

| * Polyunsaturated fatty acids | [287,288] | |

| Quercetin | [254] | |

| * Selenium | [289–291] | |

| Silibinin | [292] | |

| Silymarin | [293] | |

| Sodium fusidate | [294] | |

| * TJ-9 (Sho-saiko-to) | [295,296] | |

| * Ursodiol | [297] | |

| * Vitamin E | [298,299] | |

| * Vitamin K | [300] | |

| Whey protein | [301] | |

| Zinc | [302] | |

| Gastritis | Acupuncture | [303] |

| Antioxidant cocktail (selenium, β-carotene, and vitamins A, C and E) | [304] | |

| Astaxanthin | [305] | |

| * Curcumin | [306,307] | |

| DA-9601 | [308,309] | |

| * Garlic | [310–312] | |

| * Green tea catechins | [313–316] | |

| * Iron chelators | [195,317] | |

| Kampo | [318] | |

| Moxibustion | [303] | |

| * Rebamipide | [319,320] | |

| Red wine | [314] | |

| TJ-15 | [321] | |

| Pancreatitis | Black tea (Camellia sinensis) | [322] |

| * Curcumin | [323–325] | |

| DA-9601 | [326,327] | |

| Eicosapentaenoic acid (Omega-3 fatty acids) | [328] [329] |

|

| Erythropoietin | [330] | |

| Ghrelin | [331] | |

| * Green tea catechins | [332–334] | |

| Iron chelators | [335] | |

| Lactobacillus plantarum | [336] | |

| Leptin | [337] | |

| Ligustrazine | [338] | |

| * Melatonin/L-tryptophan | [339,340] | |

| Resveratrol | [341–343] | |

| TJ-10 | [344] | |

| TJ-45 | [345] | |

| Ursodiol | [346] | |

| Vitamin E | [347] | |

| Zinc | [348] | |

| Esophagitis/Barrett’s | DA-9601 | [349,350] |

| * Green tea catechins | [351,352] | |

| Harmaline | [353] | |

| Inositol compounds | [354] | |

| Rutin | [353] | |

| Thioproline/thiazolidine-4-carboxylic acid | [355] | |

| Prostatitis | Cernilton (pollen extract) | [356] |

| * Green tea catechins | [351,357–359] | |

| Kampo medicines | [360] | |

| * Lycopene | [361,362] | |

| Quercetin | [363] | |

| Saw palmetto | [364] | |

| * Soy | [365–367] | |

| Cystitis | * Garlic | [368,369] |

| Green tea catechins | [370] | |

| Quercetin | [371] | |

| Uro-Vaxom (E. coli extract) | [372] | |

| * Vitamin D or analogues | [373,374] |

, Indicates there is animal and/or human evidence that this CAM protects from cancer or metastases in that organ.

Traditional Chinese medicinal herbs for enema consisted of Huangqi (astragalus), Dahuang (caulis fibraureae), Huangbai (cortex phellodendri), Wubeizi (galla chinensis) and Baiji (rhizoma bletillae), mixed with 1g crude drug per milliliter by Medicament Section of Shanghai Tongji Hospital.

The finding that many of the CAMs listed in Table 1 have been shown to reduce NO species gives further weight to the role of NO in chronic inflammation and carcinogenesis. For example, aloe has been shown to inhibit cytokine-induced iNOS expression, and nitric oxide accumulation in tumor cells [22]. Nitric oxide contributes to desipramine-induced hypotension in rats [23]. Interestingly, berberine chloride can also cause an increase in eNOS expression, but it inhibits iNOS expression [24]. The inhibition of iNOS expression by berberine in vivo has been confirmed in a more recent study in hepatocytes [25]. Additionally, berberine can inhibit cytokine/lipopolysaccharide induced iNOS expression in inflammatory cells, as can butyrate, caffeic acid, cloricromene (a coumerin derviative), catalposide, curcumin, Artemisia asiatica, garlic, quercetin/quercitrin, ginkgo biloba, lactoferrin, leptin, linoleic acid, lycopene, omega-3 fatty acids, wogonin, rutin, resveratrol, selenium, black tea extracts, green tea extracts, vitamin E, Acanthopanax senticosus, cadmium, cannabinoids, alpha-lipoic acid, ginseng, silymarin, Sho-saiko-to (TJ-9), and astaxnthin [26–54]. Among many other examples, butyrate can also inhibit iNOS expression in colon cancer cells [55], and DA-6034 can inhibit iNOS expression in gastric cancer cells [56], giving some insight into their ability to protect against colitis and potentially gastritis, respectively. S-Adenosylmethionine, which protects against hepatitis, attenuates the induction of iNOS in the liver of lipopolysaccharide-treated rats and in cytokine-treated hepatocytes [57]. S-Adenosylmethionine also accelerates the re-synthesis of inhibitor kappa B alpha, blunts the activation of NF-kB and reduces the transactivation of the iNOS promoter [57]. Green tea does not only inhibit iNOS expression [58], but also directly scavenges NO [59], as do other CAMs [57,60], suggesting additional NO-related anti-inflammatory mechanisms.

The importance of NO in disease pathology so far is highlighted here by the clear and relatively consistent findings above that many of the CAMs listed in Table 1 can inhibit the induced expression of iNOS and NO production. We should mention, however, that this finding is consistent for induced expression in macrophages. In other cell types, CAMs can drive NO production [61], especially from eNOS in endothelial cells, which is indicative of their cardio-protective mechanisms [62–65]. Finally, in some cases CAMs can induce NO in unstimulated macrophages [66]. For example, ginseng can induce iNOS in resting macrophages [67]; a finding consistent with the understanding that ginseng boosts immune cell function in healthy individuals. Therefore, many of these CAMs will have differing effects depending on whether they are used in healthy people, or people with autoimmune, reactive species overload diseases. In the former case, CAMs (e.g. ginseng) can stimulate immunity; in the latter case, CAMs (e.g. ginseng) inhibit an overactive immune system, as indicated by the ability to inhibit activated macrophages.

In some instances, the ability of CAMs to inhibit NO production leads to other cancer inhibitory effects. These inhibitory effects are sometimes independent (but complementary to) NO, and sometimes dependent on nitric oxide, due to its direct impact on cell growth and apoptosis. For example, curcumin can induce melanoma cell apoptosis and cell cycle arrest [68]. This was associated with the down-regulation of NF-κB activation, iNOS and DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit expression, and up-regulation of p53, p21(Cip1), p27(Kip1) and checkpoint kinase 2. Curcumin also down-regulated constitutive NOS activity in melanoma cells. Zheng et al. concuded that curcumin arrested cell growth at the G(2)/M phase and induced apoptosis in human melanoma cells by inhibiting NF-κB activation and thus depletion of endogenous nitric oxide.

We have described the ability of many CAMs shown to prevent and/or treat reactive species overload diseases, and have presented evidence that the prevention of NO/RNS is a mechanism. However, as mentioned, the other players in inflammation and the inflammation-to-cancer sequence are also targets of CAMs. Powerful evidence for this statement comes from studies with the CAMs emerging as the more potent, successful and consistent in treating multiple high cancer risk, reactive species overload diseases. These include curcumin, green tea, resveratrol, and quercetin. For example (Figure 1), in addition to NO inhibition, curcumin (a principal curcuminoid of the Indian curry spice turmeric) inhibits NF-κB [69], inflammatory cytokines [70–74], Cox-2 [75–77], matrix metalloproteinases [75,78], pro-survival kinase pathways [79], modulate TLR signaling [80], growth factor expression [81], induces p53 [82–84], and activates anti-inflammatory peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma [85]. Green tea catechins (Figure 1) activate wild-type p53 [86–89], and protect from p53 mutation [90]. They promote pRb hypophosphorylation and activation of this tumor suppressor protein [91]. They inhibit pro-inflammatory cytokines [92–94], NF-κB [95,96], Cox-2 [97–100], growth factors such as IGF-I [101], and MMPs such as MMP-7 [102] and MMP-9 [103].

As discussed above, green tea catechins inhibit iNOS [58,104–106] and scavenge NO [107] and other free radicals [59]. Interestingly, as with many CAMs, green tea (as well as resveratrol [108] and quercetin [109]) can induce eNOS in endothelial cells, indicative of their cardio-protective effects [108,110]. Finally, they modulate TLR signaling pathways [111] and activate anti-inflammatory peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors [112].

As with green tea [88,113], resveratrol (trans-3,5,4′-trihydroxystilbene), a compound found largely in the skins of red grapes, prevents DNA damage and induces apoptosis in a p53-dependent manner [114–116]. Interestingly, resveratrol can induce the expression of the p53 target, NAG-1 [non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAID) drug-activated gene-1], a member of the transforming growth factor-beta superfamily, that has pro-apoptotic and antitumorigenesis activities [117]. Also similar to green tea, resveratrol prevents pRb hyperphosphorylation and thus the inactivation of this tumor suppressor protein. Resveratrol also inhibits MMP-2 [118] and MMP-9 [119,120], Cox-1 [121], Cox-2 [122–124], pro-inflammatory cytokines [125–127], NF-κB activation [123,124,128], and growth factors such as hepatocyte growth factor [129]. Finally, consistent with the its anti-inflammatory themed effects, resveratrol can stimulate anti-inflammatory cytokines [130] as well as anti-inflammatory PPARs [131].

Quercetin is a flavonoid found in many foods such as apples, grapes, wines, onions, berries, teas, and brassica vegetables. It is also found in some potent CAMs, including Ginkgo biloba, St. John’s Wort, and Sambucus canadensis (Elder). Quercetin mediates the down-regulation of mutant p53 [132], and upregulation of wild-type p53 [133–136]. As with resveratrol, quercetin also induces NAG-1 in a p53-dependent manner [137]. It also causes hypophosphorylation and activation of pRb [138]. It inhibits pro-inflammatory cytokines [139–142], growth factor signaling [143], kinases [134,144,145], MMPs-1,-2, and -9 [144,146]. The ability of quercetin to inhibit DNA damage [147] may be at least in part due to its ability to suppress Cox-2 [147–150] and NF-κB [139–141,147,150–153].

Concluding remarks

I have made the case that NO remains a viable candidate target for the prevention and/or treatment of radical species overload diseases, and associated cancers. However, due to the paradoxical behavior of NO, and other nodes in the inflammation-to-cancer sequence (including NF-κB), an approach that is worth further consideration and exploration is the targeting of multiple players in the cascade. CAMs have been used for thousands of years, and we are beginning to understand the mechanisms. One key mechanism of many is their anti-oxidant properties, and their ability to target multiple inflammation players simultaneously. Perhaps cocktails made up of key active components of CAMs, or synthetic drugs that partially block many of the key players (aspirin is one of these) will prove to be beneficial in treating the millions of people world-wide with autoimmune and high cancer risk, reactive species overload diseases.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH grant# 1 R21 DK071541-01A, 1P01AT003961-01A1, and the COBRE funded Center for Colon Cancer Research, NIH Grant# P20 RR17698-01.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hofseth LJ, Hussain SP, Wogan GN, Harris CC. Nitric oxide in cancer and chemoprevention. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2003;34:955–968. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01363-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ying L, Hofseth LJ. An emerging role for endothelial nitric oxide synthase in chronic inflammation and cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1407–1410. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lancaster JR, Jr, Xie K. Tumors face NO problems? Cancer Res. 2006;66:6459–6462. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fukumura D, Kashiwagi S, Jain RK. The role of nitric oxide in tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:521–534. doi: 10.1038/nrc1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hofseth LJ, Ying L. Identifying and defusing weapons of mass inflammation in carcinogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1765:74–84. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2005.08.005. Epub 2005 Sep 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wallace JL. Nitric oxide-releasing mesalamine: potential utility for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2003;35:S35–40. doi: 10.1016/s1590-8658(03)00050-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wallace JL. Nitric oxide, aspirin-triggered lipoxins and NO-aspirin in gastric protection. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2006;5:133–137. doi: 10.2174/187152806776383116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Santucci L, Wallace J, Mencarelli A, Farneti S, Morelli A, Fiorucci S. Different sensitivity of lamina propria T-cell subsets to nitric oxide-induced apoptosis explains immunomodulatory activity of a nitric oxide-releasing derivative of mesalamine in rodent colitis. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1243–1257. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li CQ, Pang B, Kiziltepe T, Trudel LJ, Engelward BP, Dedon PC, et al. Threshold effects of nitric oxide-induced toxicity and cellular responses in wild-type and p53-null human lymphoblastoid cells. Chem Res Toxicol. 2006;19:399–406. doi: 10.1021/tx050283e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hofseth LJ, Wargovich MJ. Inflammation, cancer, and targets of ginseng. J Nutr. 2007;137:183S–185S. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.1.183S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanauer SB, Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, Fedorak RN, Lukas M, MacIntosh D, et al. Human anti-tumor necrosis factor monoclonal antibody (adalimumab) in Crohn’s disease: the CLASSIC-I trial. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:323–333. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.030. quiz 591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rutgeerts P, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Reinisch W, Olson A, Johanns J, et al. Infliximab for induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2462–2476. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feld JJ, Hoofnagle JH. Mechanism of action of interferon and ribavirin in treatment of hepatitis C. Nature. 2005;436:967–972. doi: 10.1038/nature04082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giannini EG, Kane SV, Testa R, Savarino V. 5-ASA and colorectal cancer chemoprevention in inflammatory bowel disease: can we afford to wait for ‘best evidence’? Dig Liver Dis. 2005;37:723–731. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2005.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dudhgaonkar SP, Tandan SK, Kumar D, Raviprakash V, Kataria M. Influence of simultaneous inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 and inducible nitric oxide synthase in experimental colitis in rats. Inflammopharmacology. 2007;15:188–195. doi: 10.1007/s10787-007-1603-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greten FR, Eckmann L, Greten TF, Park JM, Li ZW, Egan LJ, et al. IKKbeta links inflammation and tumorigenesis in a mouse model of colitis-associated cancer. Cell. 2004;118:285–296. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neurath MF, Pettersson S, Meyer zum Buschenfelde KH, Strober W. Local administration of antisense phosphorothioate oligonucleotides to the p65 subunit of NF-kappa B abrogates established experimental colitis in mice. Nat Med. 1996;2:998–1004. doi: 10.1038/nm0996-998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maeda S, Hsu LC, Liu H, Bankston LA, Iimura M, Kagnoff MF, et al. Nod2 mutation in Crohn’s disease potentiates NF-kappaB activity and IL-1beta processing. Science. 2005;307:734–738. doi: 10.1126/science.1103685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karin M. Nuclear factor-kappaB in cancer development and progression. Nature. 2006;441:431–436. doi: 10.1038/nature04870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Habeeb F, Stables G, Bradbury F, Nong S, Cameron P, Plevin R, et al. The inner gel component of Aloe vera suppresses bacterial-induced pro-inflammatory cytokines from human immune cells. Methods. 2007;42:388–393. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwab M, Reynders V, Loitsch S, Steinhilber D, Stein J, Schroder O. Involvement of different nuclear hormone receptors in butyrate-mediated inhibition of inducible NF kappa B signalling. Mol Immunol. 2007;44:3625–3632. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.04.010. Epub 2007 May 3622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mijatovic S, Maksimovic-Ivanic D, Radovic J, Popadic D, Momcilovic M, Harhaji L, et al. Aloe-emodin prevents cytokine-induced tumor cell death: the inhibition of auto-toxic nitric oxide release as a potential mechanism. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2004;61:1805–1815. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4089-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pentel PR, Wananukul W, Scarlett W, Keyler DE. Nitric oxide contributes to desipramine-induced hypotension in rats. Hum Exp Toxicol. 1996;15:320–328. doi: 10.1177/096032719601500408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pan LR, Tang Q, Fu Q, Hu BR, Xiang JZ, Qian JQ. Roles of nitric oxide in protective effect of berberine in ethanol-induced gastric ulcer mice. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2005;26:1334–1338. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2005.00186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao X, Zhang JJ, Wang X, Bu XY, Lou YQ, Zhang GL. Effect of berberine on hepatocyte proliferation, inducible nitric oxide synthase expression, cytochrome P450 2E1 and 1A2 activities in diethylnitrosamine- and phenobarbital-treated rats. Biomed Pharmacother. 2007;12:12. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim KW, Ha KT, Park CS, Jin UH, Chang HW, Lee IS, et al. Polygonum cuspidatum, compared with baicalin and berberine, inhibits inducible nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase-2 gene expressions in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Vascul Pharmacol. 2007;47:99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2007.04.007. Epub 2007 May 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chakravortty D, Koide N, Kato Y, Sugiyama T, Mu MM, Yoshida T, et al. The inhibitory action of butyrate on lipopolysaccharide-induced nitric oxide production in RAW 264.7 murine macrophage cells. J Endotoxin Res. 2000;6:243–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Song YS, Park EH, Hur GM, Ryu YS, Lee YS, Lee JY, et al. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester inhibits nitric oxide synthase gene expression and enzyme activity. Cancer Lett. 2002;175:53–61. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(01)00787-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shin KM, Kim IT, Park YM, Ha J, Choi JW, Park HJ, et al. Anti-inflammatory effect of caffeic acid methyl ester and its mode of action through the inhibition of prostaglandin E2, nitric oxide and tumor necrosis factor-alpha production. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;68:2327–2336. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oh H, Pae HO, Oh GS, Lee SY, Chai KY, Song CE, et al. Inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthesis by catalposide from Catalpa ovata. Planta Med. 2002;68:685–689. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-33810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brouet I, Ohshima H. Curcumin, an anti-tumour promoter and anti-inflammatory agent, inhibits induction of nitric oxide synthase in activated macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;206:533–540. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reddy AM, Lee JY, Seo JH, Kim BH, Chung EY, Ryu SY, et al. Artemisolide from Artemisia asiatica: nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-kappaB) inhibitor suppressing prostaglandin E2 and nitric oxide production in macrophages. Arch Pharm Res. 2006;29:591–597. doi: 10.1007/BF02969271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang HP, Huang SY, Chen YH. Modulation of cytokine secretion by garlic oil derivatives is associated with suppressed nitric oxide production in stimulated macrophages. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:2530–2534. doi: 10.1021/jf048601n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park YM, Won JH, Yun KJ, Ryu JH, Han YN, Choi SK, et al. Preventive effect of Ginkgo biloba extract (GBB) on the lipopolysaccharide-induced expressions of inducible nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase-2 via suppression of nuclear factor-kappaB in RAW 264.7 cells. Biol Pharm Bull. 2006;29:985–990. doi: 10.1248/bpb.29.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wadsworth TL, Koop DR. Effects of Ginkgo biloba extract (EGb 761) and quercetin on lipopolysaccharide-induced release of nitric oxide. Chem Biol Interact. 2001;137:43–58. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(01)00208-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kobuchi H, Droy-Lefaix MT, Christen Y, Packer L. Ginkgo biloba extract (EGb 761): inhibitory effect on nitric oxide production in the macrophage cell line RAW 264.7. Biochem Pharmacol. 1997;53:897–903. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(96)00873-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Choe YH, Lee SW. Effect of lactoferrin on the production of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and nitric oxide. J Cell Biochem. 1999;76:30–36. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4644(20000101)76:1<30::aid-jcb4>3.3.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raso GM, Pacilio M, Esposito E, Coppola A, Di Carlo R, Meli R. Leptin potentiates IFN-gamma-induced expression of nitric oxide synthase and cyclo-oxygenase-2 in murine macrophage J774A.1. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;137:799–804. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Iwakiri Y, Sampson DA, Allen KG. Suppression of cyclooxygenase-2 and inducible nitric oxide synthase expression by conjugated linoleic acid in murine macrophages. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2002;67:435–443. doi: 10.1054/plef.2002.0454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rafi MM, Yadav PN, Reyes M. Lycopene inhibits LPS-induced proinflammatory mediator inducible nitric oxide synthase in mouse macrophage cells. J Food Sci. 2007;72:S069–074. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2006.00219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ohata T, Fukuda K, Takahashi M, Sugimura T, Wakabayashi K. Suppression of nitric oxide production in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophage cells by omega 3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1997;88:234–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1997.tb00372.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim BH, Cho SM, Reddy AM, Kim YS, Min KR, Kim Y. Down-regulatory effect of quercitrin gallate on nuclear factor-kappa B-dependent inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophages RAW 264.7. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;69:1577–1583. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.03.014. Epub 2005 Apr 1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsai SH, Lin-Shiau SY, Lin JK. Suppression of nitric oxide synthase and the down-regulation of the activation of NFkappaB in macrophages by resveratrol. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;126:673–680. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yun CH, Yang JS, Kang SS, Yang Y, Cho JH, Son CG, et al. NF-kappaB signaling pathway, not IFN-beta/STAT1, is responsible for the selenium suppression of LPS-induced nitric oxide production. Int Immunopharmacol. 2007;7:1192–1198. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2007.05.002. Epub 2007 May 1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lin YL, Tsai SH, Lin-Shiau SY, Ho CT, Lin JK. Theaflavin-3,3′-digallate from black tea blocks the nitric oxide synthase by down-regulating the activation of NF-kappaB in macrophages. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;367:379–388. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00953-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hattori S, Hattori Y, Banba N, Kasai K, Shimoda S. Pentamethyl-hydroxychromane, vitamin E derivative, inhibits induction of nitric oxide synthase by bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Biochem Mol Biol Int. 1995;35:177–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lin QY, Jin LJ, Ma YS, Shi M, Xu YP. Acanthopanax senticosus inhibits nitric oxide production in murine macrophages in vitro and in vivo. Phytother Res. 2007;21:879–883. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim HM, Lee EH, Shin TY, Lee KN, Lee JS. Taraxacum officinale restores inhibition of nitric oxide production by cadmium in mouse peritoneal macrophages. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 1998;20:283–297. doi: 10.3109/08923979809038545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gallily R, Yamin A, Waksmann Y, Ovadia H, Weidenfeld J, Bar-Joseph A, et al. Protection against septic shock and suppression of tumor necrosis factor alpha and nitric oxide production by dexanabinol (HU-211), a nonpsychotropic cannabinoid. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;283:918–924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guo Q, Tirosh O, Packer L. Inhibitory effect of alpha-lipoic acid and its positively charged amide analogue on nitric oxide production in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Biochem Pharmacol. 2001;61:547–554. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00569-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Seo JY, Lee JH, Kim NW, Kim YJ, Chang SH, Ko NY, et al. Inhibitory effects of a fermented ginseng extract, BST204, on the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase and nitric oxide production in lipopolysaccharide-activated murine macrophages. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2005;57:911–918. doi: 10.1211/0022357056497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shen SC, Lee WR, Lin HY, Huang HC, Ko CH, Yang LL, et al. In vitro and in vivo inhibitory activities of rutin, wogonin, and quercetin on lipopolysaccharide-induced nitric oxide and prostaglandin E(2) production. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;446:187–194. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01792-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sakaguchi S, Furusawa S, Yokota K, Sasaki K, Takayanagi Y. Depressive effect of a traditional Chinese medicine (sho-saiko-to) on endotoxin-induced nitric oxide formation in activated murine macrophage J774A.1 cells. Biol Pharm Bull. 1995;18:621–623. doi: 10.1248/bpb.18.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee SJ, Bai SK, Lee KS, Namkoong S, Na HJ, Ha KS, et al. Astaxanthin inhibits nitric oxide production and inflammatory gene expression by suppressing I(kappa)B kinase-dependent NF-kappaB activation. Mol Cells. 2003;16:97–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sasahara Y, Mutoh M, Takahashi M, Fukuda K, Tanaka N, Sugimura T, et al. Suppression of promoter-dependent transcriptional activity of inducible nitric oxide synthase by sodium butyrate in colon cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2002;177:155–161. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(01)00778-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee JS, Kim HS, Hahm KB, Sohn MW, Yoo M, Johnson JA, et al. Inhibitory effects of 7-carboxymethyloxy-3′,4′,5-trimethoxyflavone (DA-6034) on Helicobacter pylori-induced NF-kappa B activation and iNOS expression in AGS cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1095:527–535. doi: 10.1196/annals.1397.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Majano PL, Garcia-Monzon C, Garcia-Trevijano ER, Corrales FJ, Camara J, Ortiz P, et al. S-Adenosylmethionine modulates inducible nitric oxide synthase gene expression in rat liver and isolated hepatocytes. J Hepatol. 2001;35:692–699. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(01)00208-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chan MM, Fong D, Ho CT, Huang HI. Inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase gene expression and enzyme activity by epigallocatechin gallate, a natural product from green tea. Biochem Pharmacol. 1997;54:1281–1286. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(97)00504-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nakagawa T, Yokozawa T. Direct scavenging of nitric oxide and superoxide by green tea. Food Chem Toxicol. 2002;40:1745–1750. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(02)00169-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Takahama U, Hirota S, Oniki T. Quercetin-dependent scavenging of reactive nitrogen species derived from nitric oxide and nitrite in the human oral cavity: interaction of quercetin with salivary redox components. Arch Oral Biol. 2006;51:629–639. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2006.02.011. Epub 2006 Apr 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hattori Y, Kasai K, Sekiguchi Y, Hattori S, Banba N, Shimoda S. The herbal medicine sho-saiko-to induces nitric oxide synthase in rat hepatocytes. Life Sci. 1995;56:PL143–148. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(94)00483-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Leikert JF, Rathel TR, Wohlfart P, Cheynier V, Vollmar AM, Dirsch VM. Red wine polyphenols enhance endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression and subsequent nitric oxide release from endothelial cells. Circulation. 2002;106:1614–1617. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000034445.31543.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wallerath T, Poleo D, Li H, Forstermann U. Red wine increases the expression of human endothelial nitric oxide synthase: a mechanism that may contribute to its beneficial cardiovascular effects. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:471–478. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02826-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Anter E, Thomas SR, Schulz E, Shapira OM, Vita JA, Keaney JF., Jr Activation of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase by the p38 MAPK in response to black tea polyphenols. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:46637–46643. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405547200. Epub 42004 Aug 46627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Burger D, Lei M, Geoghegan-Morphet N, Lu X, Xenocostas A, Feng Q. Erythropoietin protects cardiomyocytes from apoptosis via up-regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;72:51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.06.026. Epub 2006 Jun 2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ignacio SR, Ferreira JL, Almeida MB, Kubelka CF. Nitric oxide production by murine peritoneal macrophages in vitro and in vivo treated with Phyllanthus tenellus extracts. J Ethnopharmacol. 2001;74:181–187. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(00)00371-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Friedl R, Moeslinger T, Kopp B, Spieckermann PG. Stimulation of nitric oxide synthesis by the aqueous extract of Panax ginseng root in RAW 264.7 cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;134:1663–1670. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zheng M, Ekmekcioglu S, Walch ET, Tang CH, Grimm EA. Inhibition of nuclear factor-kappaB and nitric oxide by curcumin induces G2/M cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in human melanoma cells. Melanoma Res. 2004;14:165–171. doi: 10.1097/01.cmr.0000129374.76399.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bachmeier BE, Mohrenz IV, Mirisola V, Schleicher E, Romeo F, Hohneke C, et al. Curcumin Down-Regulates the Inflammatory Cytokines CXCL1 and -2 in Breast Cancer Cells via NF{kappa}B. Carcinogenesis. 2007;13:13. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fahey AJ, Adrian Robins R, Constantinescu CS. Curcumin modulation of IFN-beta and IL-12 signalling and cytokine induction in human T cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2007;11:1129–1137. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2007.00089.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yao QH, Wang DQ, Cui CC, Yuan ZY, Chen SB, Yao XW, et al. Curcumin ameliorates left ventricular function in rabbits with pressure overload: inhibition of the remodeling of the left ventricular collagen network associated with suppression of myocardial tumor necrosis factor-alpha and matrix metalloproteinase-2 expression. Biol Pharm Bull. 2004;27:198–202. doi: 10.1248/bpb.27.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Abe Y, Hashimoto S, Horie T. Curcumin inhibition of inflammatory cytokine production by human peripheral blood monocytes and alveolar macrophages. Pharmacol Res. 1999;39:41–47. doi: 10.1006/phrs.1998.0404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kumar A, Dhawan S, Hardegen NJ, Aggarwal BB. Curcumin (Diferuloylmethane) inhibition of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-mediated adhesion of monocytes to endothelial cells by suppression of cell surface expression of adhesion molecules and of nuclear factor-kappaB activation. Biochem Pharmacol. 1998;55:775–783. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(97)00557-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chan MM. Inhibition of tumor necrosis factor by curcumin, a phytochemical. Biochem Pharmacol. 1995;49:1551–1556. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(95)00171-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shakibaei M, John T, Schulze-Tanzil G, Lehmann I, Mobasheri A. Suppression of NF-kappaB activation by curcumin leads to inhibition of expression of cyclo-oxygenase-2 and matrix metalloproteinase-9 in human articular chondrocytes: Implications for the treatment of osteoarthritis. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;73:1434–1445. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.01.005. Epub 2007 Jan 1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sharma C, Kaur J, Shishodia S, Aggarwal BB, Ralhan R. Curcumin down regulates smokeless tobacco-induced NF-kappaB activation and COX-2 expression in human oral premalignant and cancer cells. Toxicology. 2006;228:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2006.07.027. Epub 2006 Aug 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Goel A, Boland CR, Chauhan DP. Specific inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) expression by dietary curcumin in HT-29 human colon cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2001;172:111–118. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(01)00655-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Swarnakar S, Ganguly K, Kundu P, Banerjee A, Maity P, Sharma AV. Curcumin regulates expression and activity of matrix metalloproteinases 9 and 2 during prevention and healing of indomethacin-induced gastric ulcer. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:9409–9415. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413398200. Epub 2004 Dec 9422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Deeb D, Jiang H, Gao X, Al-Holou S, Danyluk AL, Dulchavsky SA, et al. Curcumin [1,7-bis(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1-6-heptadine-3,5-dione; C21H20O6] sensitizes human prostate cancer cells to tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand/Apo2L-induced apoptosis by suppressing nuclear factor-kappaB via inhibition of the prosurvival Akt signaling pathway. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;321:616–625. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.117721. Epub 2007 Feb 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Youn HS, Saitoh SI, Miyake K, Hwang DH. Inhibition of homodimerization of Toll-like receptor 4 by curcumin. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;72:62–69. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.03.022. Epub 2006 Apr 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chen A, Xu J, Johnson AC. Curcumin inhibits human colon cancer cell growth by suppressing gene expression of epidermal growth factor receptor through reducing the activity of the transcription factor Egr-1. Oncogene. 2006;25:278–287. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Liu E, Wu J, Cao W, Zhang J, Liu W, Jiang X, et al. Curcumin induces G2/M cell cycle arrest in a p53-dependent manner and upregulates ING4 expression in human glioma. J Neurooncol. 2007;85:263–270. doi: 10.1007/s11060-007-9421-4. Epub 2007 Jun 2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jee SH, Shen SC, Tseng CR, Chiu HC, Kuo ML. Curcumin induces a p53-dependent apoptosis in human basal cell carcinoma cells. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;111:656–661. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Liontas A, Yeger H. Curcumin and resveratrol induce apoptosis and nuclear translocation and activation of p53 in human neuroblastoma. Anticancer Res. 2004;24:987–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhang M, Deng C, Zheng J, Xia J, Sheng D. Curcumin inhibits trinitrobenzene sulphonic acid-induced colitis in rats by activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma. Int Immunopharmacol. 2006;6:1233–1242. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2006.02.013. Epub 2006 Apr 1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lu YP, Lou YR, Li XH, Xie JG, Brash D, Huang MT, et al. Stimulatory effect of oral administration of green tea or caffeine on ultraviolet light-induced increases in epidermal wild-type p53, p21(WAF1/CIP1), and apoptotic sunburn cells in SKH-1 mice. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4785–4791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Amin AR, Thakur VS, Paul RK, Feng GS, Qu CK, Mukhtar H, et al. SHP-2 tyrosine phosphatase inhibits p73-dependent apoptosis and expression of a subset of p53 target genes induced by EGCG. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:5419–5424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700642104. Epub 2007 Mar 5416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kuo PL, Lin CC. Green tea constituent (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits Hep G2 cell proliferation and induces apoptosis through p53-dependent and Fas-mediated pathways. J Biomed Sci. 2003;10:219–227. doi: 10.1007/BF02256057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hofmann CS, Sonenshein GE. Green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin-3 gallate induces apoptosis of proliferating vascular smooth muscle cells via activation of p53. Faseb J. 2003;17:702–704. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0665fje. Epub 2003 Feb 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lu YP, Lou YR, Liao J, Xie JG, Peng QY, Yang CS, et al. Administration of green tea or caffeine enhances the disappearance of UVB-induced patches of mutant p53 positive epidermal cells in SKH-1 mice. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:1465–1472. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi086. Epub 2005 Apr 1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ahmad N, Adhami VM, Gupta S, Cheng P, Mukhtar H. Role of the retinoblastoma (pRb)-E2F/DP pathway in cancer chemopreventive effects of green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin-3-gallate. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2002;398:125–131. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fujiki H, Suganuma M, Kurusu M, Okabe S, Imayoshi Y, Taniguchi S, et al. New TNF-alpha releasing inhibitors as cancer preventive agents from traditional herbal medicine and combination cancer prevention study with EGCG and sulindac or tamoxifen. Mutat Res. 2003;523–524:119–125. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(02)00327-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hsu SD, Dickinson DP, Qin H, Borke J, Ogbureke KU, Winger JN, et al. Green tea polyphenols reduce autoimmune symptoms in a murine model for human Sjogren’s syndrome and protect human salivary acinar cells from TNF-alpha-induced cytotoxicity. Autoimmunity. 2007;40:138–147. doi: 10.1080/08916930601167343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Abe K, Ijiri M, Suzuki T, Taguchi K, Koyama Y, Isemura M. Green tea with a high catechin content suppresses inflammatory cytokine expression in the galactosamine-injured rat liver. Biomed Res. 2005;26:187–192. doi: 10.2220/biomedres.26.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yang F, Oz HS, Barve S, de Villiers WJ, McClain CJ, Varilek GW. The green tea polyphenol (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate blocks nuclear factor-kappa B activation by inhibiting I kappa B kinase activity in the intestinal epithelial cell line IEC-6. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;60:528–533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Aktas O, Prozorovski T, Smorodchenko A, Savaskan NE, Lauster R, Kloetzel PM, et al. Green tea epigallocatechin-3-gallate mediates T cellular NF-kappa B inhibition and exerts neuroprotection in autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2004;173:5794–5800. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.9.5794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hong J, Smith TJ, Ho CT, August DA, Yang CS. Effects of purified green and black tea polyphenols on cyclooxygenase- and lipoxygenase-dependent metabolism of arachidonic acid in human colon mucosa and colon tumor tissues. Biochem Pharmacol. 2001;62:1175–1183. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00767-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hussain T, Gupta S, Adhami VM, Mukhtar H. Green tea constituent epigallocatechin-3-gallate selectively inhibits COX-2 without affecting COX-1 expression in human prostate carcinoma cells. Int J Cancer. 2005;113:660–669. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Peng G, Dixon DA, Muga SJ, Smith TJ, Wargovich MJ. Green tea polyphenol (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits cyclooxygenase-2 expression in colon carcinogenesis. Mol Carcinog. 2006;45:309–319. doi: 10.1002/mc.20166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hou DX, Masuzaki S, Hashimoto F, Uto T, Tanigawa S, Fujii M, et al. Green tea proanthocyanidins inhibit cyclooxygenase-2 expression in LPS-activated mouse macrophages: molecular mechanisms and structure-activity relationship. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;460:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.01.009. Epub 2007 Jan 2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Adhami VM, Siddiqui IA, Ahmad N, Gupta S, Mukhtar H. Oral consumption of green tea polyphenols inhibits insulin-like growth factor-I-induced signaling in an autochthonous mouse model of prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8715–8722. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Oneda H, Shiihara M, Inouye K. Inhibitory effects of green tea catechins on the activity of human matrix metalloproteinase 7 (matrilysin) J Biochem. 2003;133:571–576. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvg073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Yun JH, Pang EK, Kim CS, Yoo YJ, Cho KS, Chai JK, et al. Inhibitory effects of green tea polyphenol (−)-epigallocatechin gallate on the expression of matrix metalloproteinase-9 and on the formation of osteoclasts. J Periodontal Res. 2004;39:300–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2004.00743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Srivastava RC, Husain MM, Hasan SK, Athar M. Green tea polyphenols and tannic acid act as potent inhibitors of phorbol ester-induced nitric oxide generation in rat hepatocytes independent of their antioxidant properties. Cancer Lett. 2000;153:1–5. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(99)00400-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Tedeschi E, Menegazzi M, Yao Y, Suzuki H, Forstermann U, Kleinert H. Green tea inhibits human inducible nitric-oxide synthase expression by down-regulating signal transducer and activator of transcription-1alpha activation. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65:111–120. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chen JH, Tipoe GL, Liong EC, So HS, Leung KM, Tom WM, et al. Green tea polyphenols prevent toxin-induced hepatotoxicity in mice by down-regulating inducible nitric oxide-derived prooxidants. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:742–751. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.3.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Joshi S, Hasan SK, Chandra R, Husain MM, Srivastava RC. Scavenging action of zinc and green tea polyphenol on cisplatin and nickel induced nitric oxide generation and lipid peroxidation in rats. Biomed Environ Sci. 2004;17:402–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Wallerath T, Deckert G, Ternes T, Anderson H, Li H, Witte K, et al. Resveratrol, a polyphenolic phytoalexin present in red wine, enhances expression and activity of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Circulation. 2002;106:1652–1658. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000029925.18593.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Machha A, Achike FI, Mustafa AM, Mustafa MR. Quercetin, a flavonoid antioxidant, modulates endothelium-derived nitric oxide bioavailability in diabetic rat aortas. Nitric Oxide. 2007;16:442–447. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2007.04.001. Epub 2007 Apr 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lorenz M, Wessler S, Follmann E, Michaelis W, Dusterhoft T, Baumann G, et al. A constituent of green tea, epigallocatechin-3-gallate, activates endothelial nitric oxide synthase by a phosphatidylinositol-3-OH-kinase-, cAMP-dependent protein kinase-, and Akt-dependent pathway and leads to endothelial-dependent vasorelaxation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:6190–6195. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309114200. Epub 2003 Nov 6124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Youn HS, Lee JY, Saitoh SI, Miyake K, Kang KW, Choi YJ, et al. Suppression of MyD88- and TRIF-dependent signaling pathways of Toll-like receptor by (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate, a polyphenol component of green tea. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;72:850–859. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.06.021. Epub 2006 Aug 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lee K. Transactivation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha by green tea extracts. J Vet Sci. 2004;5:325–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Schwarz A, Maeda A, Gan D, Mammone T, Matsui MS, Schwarz T. Green Tea Phenol Extracts Reduce UVB-induced DNA Damage in Human Cells via Interleukin-12. Photochem Photobiol. 2008;7:7. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2007.00265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Gatz SA, Keimling M, Baumann C, Dork T, Debatin KM, Fulda S, et al. Resveratrol modulates DNA double-strand break repair pathways in an ATM/ATR-p53- and -Nbs1-dependent manner. Carcinogenesis. 2008;3:3. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Huang C, Ma WY, Goranson A, Dong Z. Resveratrol suppresses cell transformation and induces apoptosis through a p53-dependent pathway. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20:237–242. doi: 10.1093/carcin/20.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.She QB, Bode AM, Ma WY, Chen NY, Dong Z. Resveratrol-induced activation of p53 and apoptosis is mediated by extracellular-signal-regulated protein kinases and p38 kinase. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1604–1610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Baek SJ, Wilson LC, Eling TE. Resveratrol enhances the expression of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug-activated gene (NAG-1) by increasing the expression of p53. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:425–434. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.3.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Gagliano N, Moscheni C, Torri C, Magnani I, Bertelli AA, Gioia M. Effect of resveratrol on matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) and Secreted Protein Acidic and Rich in Cysteine (SPARC) on human cultured glioblastoma cells. Biomed Pharmacother. 2005;59:359–364. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Woo JH, Lim JH, Kim YH, Suh SI, Min DS, Chang JS, et al. Resveratrol inhibits phorbol myristate acetate-induced matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression by inhibiting JNK and PKC delta signal transduction. Oncogene. 2004;23:1845–1853. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Yu H, Pan C, Zhao S, Wang Z, Zhang H, Wu W. Resveratrol inhibits tumor necrosis factor-alpha-mediated matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression and invasion of human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Biomed Pharmacother. 2007;22:22. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Szewczuk LM, Forti L, Stivala LA, Penning TM. Resveratrol is a peroxidase-mediated inactivator of COX-1 but not COX-2: a mechanistic approach to the design of COX-1 selective agents. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:22727–22737. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314302200. Epub 22004 Mar 22712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Subbaramaiah K, Chung WJ, Michaluart P, Telang N, Tanabe T, Inoue H, et al. Resveratrol inhibits cyclooxygenase-2 transcription and activity in phorbol ester-treated human mammary epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:21875–21882. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.34.21875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Banerjee S, Bueso-Ramos C, Aggarwal BB. Suppression of 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene-induced mammary carcinogenesis in rats by resveratrol: role of nuclear factor-kappaB, cyclooxygenase 2, and matrix metalloprotease 9. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4945–4954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Kundu JK, Shin YK, Kim SH, Surh YJ. Resveratrol inhibits phorbol ester-induced expression of COX-2 and activation of NF-kappaB in mouse skin by blocking IkappaB kinase activity. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:1465–1474. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi349. Epub 2006 Feb 1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Zhong M, Cheng GF, Wang WJ, Guo Y, Zhu XY, Zhang JT. Inhibitory effect of resveratrol on interleukin 6 release by stimulated peritoneal macrophages of mice. Phytomedicine. 1999;6:79–84. doi: 10.1016/S0944-7113(99)80039-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Wirleitner B, Schroecksnadel K, Winkler C, Schennach H, Fuchs D. Resveratrol suppresses interferon-gamma-induced biochemical pathways in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells in vitro. Immunol Lett. 2005;100:159–163. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2005.03.008. Epub 2005 Apr 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Lee B, Moon SK. Resveratrol inhibits TNF-alpha-induced proliferation and matrix metalloproteinase expression in human vascular smooth muscle cells. J Nutr. 2005;135:2767–2773. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.12.2767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Manna SK, Mukhopadhyay A, Aggarwal BB. Resveratrol suppresses TNF-induced activation of nuclear transcription factors NF-kappa B, activator protein-1, and apoptosis: potential role of reactive oxygen intermediates and lipid peroxidation. J Immunol. 2000;164:6509–6519. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.12.6509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.De Ledinghen V, Monvoisin A, Neaud V, Krisa S, Payrastre B, Bedin C, et al. Trans-resveratrol, a grapevine-derived polyphenol, blocks hepatocyte growth factor-induced invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Int J Oncol. 2001;19:83–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Rachon D, Rimoldi G, Wuttke W. In vitro effects of genistein and resveratrol on the production of interferon-gamma (IFNgamma) and interleukin-10 (IL-10) by stimulated murine splenocytes. Phytomedicine. 2006;13:419–424. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2005.10.006. Epub 2005 Nov 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Ulrich S, Loitsch SM, Rau O, von Knethen A, Brune B, Schubert-Zsilavecz M, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma as a molecular target of resveratrol-induced modulation of polyamine metabolism. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7348–7354. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Avila MA, Velasco JA, Cansado J, Notario V. Quercetin mediates the down-regulation of mutant p53 in the human breast cancer cell line MDA-MB468. Cancer Res. 1994;54:2424–2428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Shi M, Wang FS, Wu ZZ. Synergetic anticancer effect of combined quercetin and recombinant adenoviral vector expressing human wild-type p53, GM-CSF and B7-1 genes on hepatocellular carcinoma cells in vitro. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:73–78. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i1.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Ye R, Goodarzi AA, Kurz EU, Saito S, Higashimoto Y, Lavin MF, et al. The isoflavonoids genistein and quercetin activate different stress signaling pathways as shown by analysis of site-specific phosphorylation of ATM, p53 and histone H2AX. DNA Repair (Amst) 2004;3:235–244. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2003.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Kuo PC, Liu HF, Chao JI. Survivin and p53 modulate quercetin-induced cell growth inhibition and apoptosis in human lung carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:55875–55885. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407985200. Epub 52004 Sep 55829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Mertens-Talcott SU, Bomser JA, Romero C, Talcott ST, Percival SS. Ellagic acid potentiates the effect of quercetin on p21waf1/cip1, p53, and MAP-kinases without affecting intracellular generation of reactive oxygen species in vitro. J Nutr. 2005;135:609–614. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.3.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Lim JH, Park JW, Min DS, Chang JS, Lee YH, Park YB, et al. NAG-1 up-regulation mediated by EGR-1 and p53 is critical for quercetin-induced apoptosis in HCT116 colon carcinoma cells. Apoptosis. 2007;12:411–421. doi: 10.1007/s10495-006-0576-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Vijayababu MR, Kanagaraj P, Arunkumar A, Ilangovan R, Aruldhas MM, Arunakaran J. Quercetin-induced growth inhibition and cell death in prostatic carcinoma cells (PC-3) are associated with increase in p21 and hypophosphorylated retinoblastoma proteins expression. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2005;131:765–771. doi: 10.1007/s00432-005-0005-4. Epub 2005 Nov 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Ruiz PA, Braune A, Holzlwimmer G, Quintanilla-Fend L, Haller D. Quercetin inhibits TNF-induced NF-kappaB transcription factor recruitment to proinflammatory gene promoters in murine intestinal epithelial cells. J Nutr. 2007;137:1208–1215. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.5.1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Nair MP, Mahajan S, Reynolds JL, Aalinkeel R, Nair H, Schwartz SA, et al. The flavonoid quercetin inhibits proinflammatory cytokine (tumor necrosis factor alpha) gene expression in normal peripheral blood mononuclear cells via modulation of the NF-kappa beta system. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2006;13:319–328. doi: 10.1128/CVI.13.3.319-328.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Sato M, Miyazaki T, Kambe F, Maeda K, Seo H. Quercetin, a bioflavonoid, inhibits the induction of interleukin 8 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression by tumor necrosis factor-alpha in cultured human synovial cells. J Rheumatol. 1997;24:1680–1684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Wadsworth TL, Koop DR. Effects of the wine polyphenolics quercetin and resveratrol on pro-inflammatory cytokine expression in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;57:941–949. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Huynh H, Nguyen TT, Chan E, Tran E. Inhibition of ErbB-2 and ErbB-3 expression by quercetin prevents transforming growth factor alpha (TGF-alpha)-and epidermal growth factor (EGF)-induced human PC-3 prostate cancer cell proliferation. Int J Oncol. 2003;23:821–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Huang YT, Hwang JJ, Lee PP, Ke FC, Huang JH, Huang CJ, et al. Effects of luteolin and quercetin, inhibitors of tyrosine kinase, on cell growth and metastasis-associated properties in A431 cells overexpressing epidermal growth factor receptor. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;128:999–1010. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Lee LT, Huang YT, Hwang JJ, Lee PP, Ke FC, Nair MP, et al. Blockade of the epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase activity by quercetin and luteolin leads to growth inhibition and apoptosis of pancreatic tumor cells. Anticancer Res. 2002;22:1615–1627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Song L, Xu M, Lopes-Virella MF, Huang Y. Quercetin inhibits matrix metalloproteinase-1 expression in human vascular endothelial cells through extracellular signal-regulated kinase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2001;391:72–78. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Lin SY, Tsai SJ, Wang LH, Wu MF, Lee H. Protection by quercetin against cooking oil fumes-induced DNA damage in human lung adenocarcinoma CL-3 cells: role of COX-2. Nutr Cancer. 2002;44:95–101. doi: 10.1207/S15327914NC441_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Chen YC, Shen SC, Lee WR, Hou WC, Yang LL, Lee TJ. Inhibition of nitric oxide synthase inhibitors and lipopolysaccharide induced inducible NOS and cyclooxygenase-2 gene expressions by rutin, quercetin, and quercetin pentaacetate in RAW 264.7 macrophages. J Cell Biochem. 2001;82:537–548. doi: 10.1002/jcb.1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Banerjee T, Van der Vliet A, Ziboh VA. Downregulation of COX-2 and iNOS by amentoflavone and quercetin in A549 human lung adenocarcinoma cell line. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2002;66:485–492. doi: 10.1054/plef.2002.0387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Garcia-Mediavilla V, Crespo I, Collado PS, Esteller A, Sanchez-Campos S, Tunon MJ, et al. The anti-inflammatory flavones quercetin and kaempferol cause inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase, cyclooxygenase-2 and reactive C-protein, and down-regulation of the nuclear factor kappaB pathway in Chang Liver cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;557:221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.11.014. Epub 2006 Nov 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Wattel A, Kamel S, Prouillet C, Petit JP, Lorget F, Offord E, et al. Flavonoid quercetin decreases osteoclastic differentiation induced by RANKL via a mechanism involving NF kappa B and AP-1. J Cell Biochem. 2004;92:285–295. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Martinez-Florez S, Gutierrez-Fernandez B, Sanchez-Campos S, Gonzalez-Gallego J, Tunon MJ. Quercetin attenuates nuclear factor-kappaB activation and nitric oxide production in interleukin-1beta-activated rat hepatocytes. J Nutr. 2005;135:1359–1365. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.6.1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Chen JC, Ho FM, Pei-Dawn Lee C, Chen CP, Jeng KC, Hsu HB, et al. Inhibition of iNOS gene expression by quercetin is mediated by the inhibition of IkappaB kinase, nuclear factor-kappa B and STAT1, and depends on heme oxygenase-1 induction in mouse BV-2 microglia. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;521:9–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.08.005. Epub 2005 Sep 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Korkina L, Suprun M, Petrova A, Mikhal’chik E, Luci A, De Luca C. The protective and healing effects of a natural antioxidant formulation based on ubiquinol and Aloe vera against dextran sulfate-induced ulcerative colitis in rats. Biofactors. 2003;18:255–264. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520180228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Varghese AK, Verdu EF, Bercik P, Khan WI, Blennerhassett PA, Szechtman H, et al. Antidepressants attenuate increased susceptibility to colitis in a murine model of depression. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1743–1753. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Zhou H, Mineshita S. The effect of berberine chloride on experimental colitis in rats in vivo and in vitro. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;294:822–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Luhrs H, Gerke T, Muller JG, Melcher R, Schauber J, Boxberge F, et al. Butyrate inhibits NF-kappaB activation in lamina propria macrophages of patients with ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:458–466. doi: 10.1080/003655202317316105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Medina V, Afonso JJ, Alvarez-Arguelles H, Hernandez C, Gonzalez F. Sodium butyrate inhibits carcinoma development in a 1,2-dimethylhydrazine-induced rat colon cancer. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1998;22:14–17. doi: 10.1177/014860719802200114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Perrin P, Cassagnau E, Burg C, Patry Y, Vavasseur F, Harb J, et al. An interleukin 2/sodium butyrate combination as immunotherapy for rat colon cancer peritoneal carcinomatosis. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1697–1708. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90810-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Fitzpatrick LR, Wang J, Le T. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester, an inhibitor of nuclear factor-kappaB, attenuates bacterial peptidoglycan polysaccharide-induced colitis in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;299:915–920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Kim SW, Choi SC, Choi EY, Kim KS, Oh JM, Lee HJ, et al. Catalposide, a compound isolated from catalpa ovata, attenuates induction of intestinal epithelial proinflammatory gene expression and reduces the severity of trinitrobenzene sulfonic Acid-induced colitis in mice. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10:564–572. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200409000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Matsumoto S, Nagaoka M, Hara T, Kimura-Takagi I, Mistuyama K, Ueyama S. Fucoidan derived from Cladosiphon okamuranus Tokida ameliorates murine chronic colitis through the down-regulation of interleukin-6 production on colonic epithelial cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;136:432–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02462.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Fries W, Mazzon E, Sturiale S, Giofre MR, Lo Presti MA, Cuzzocrea S, et al. A protective effect of the synthetic coumarine derivative Cloricromene against DNB-colitis in the rat. Life Sci. 2004;74:2749–2756. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Salh B, Assi K, Templeman V, Parhar K, Owen D, Gomez-Munoz A, et al. Curcumin attenuates DNB-induced murine colitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2003;285:G235–243. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00449.2002. Epub 2003 Mar 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Billerey-Larmonier C, Uno JK, Larmonier N, Midura AJ, Timmermann B, Ghishan FK, et al. Protective effects of dietary curcumin in mouse model of chemically induced colitis are strain dependent. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;15:15. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Johnson JJ, Mukhtar H. Curcumin for chemoprevention of colon cancer. Cancer Lett. 2007;255:170–181. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.03.005. Epub 2007 Apr 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Volate SR, Davenport DM, Muga SJ, Wargovich MJ. Modulation of aberrant crypt foci and apoptosis by dietary herbal supplements (quercetin, curcumin, silymarin, ginseng and rutin) Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:1450–1456. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi089. Epub 2005 Apr 1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Kawamori T, Lubet R, Steele VE, Kelloff GJ, Kaskey RB, Rao CV, et al. Chemopreventive effect of curcumin, a naturally occurring anti-inflammatory agent, during the promotion/progression stages of colon cancer. Cancer Res. 1999;59:597–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Pereira MA, Grubbs CJ, Barnes LH, Li H, Olson GR, Eto I, et al. Effects of the phytochemicals, curcumin and quercetin, upon azoxymethane-induced colon cancer and 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene-induced mammary cancer in rats. Carcinogenesis. 1996;17:1305–1311. doi: 10.1093/carcin/17.6.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Rao CV, Rivenson A, Simi B, Reddy BS. Chemoprevention of colon carcinogenesis by dietary curcumin, a naturally occurring plant phenolic compound. Cancer Res. 1995;55:259–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Huang MT, Lou YR, Ma W, Newmark HL, Reuhl KR, Conney AH. Inhibitory effects of dietary curcumin on forestomach, duodenal, and colon carcinogenesis in mice. Cancer Res. 1994;54:5841–5847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Ahn BO, Ko KH, Oh TY, Cho H, Kim WB, Lee KJ, et al. Efficacy of use of colonoscopy in dextran sulfate sodium induced ulcerative colitis in rats: the evaluation of the effects of antioxidant by colonoscopy. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2001;16:174–181. doi: 10.1007/s003840000282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Nam SY, Kim JS, Kim JM, Lee JY, Kim N, Jung HC, et al. DA-6034, a derivative of flavonoid, prevents and ameliorates dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis and inhibits colon carcinogenesis. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2008;233:180–191. doi: 10.3181/0707-RM-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Yuan H, Ji WS, Wu KX, Jiao JX, Sun LH, Feng YT. Anti-inflammatory effect of Diammonium Glycyrrhizinate in a rat model of ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:4578–4581. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i28.4578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175.Winkler J, Butler R, Symonds E. Fructo-oligosaccharide reduces inflammation in a dextran sodium sulphate mouse model of colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:52–58. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9224-z. Epub 2006 Dec 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]