Abstract

Context

High rates of alcohol misuse after deployment have been reported among personnel returning from past conflicts, yet investigations of alcohol misuse after return from the current wars in Iraq and Afghanistan are lacking.

Objectives

To determine whether deployment with combat exposures was associated with new-onset or continued alcohol consumption, binge drinking, and alcohol-related problems.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Data were from Millennium Cohort Study participants who completed both a baseline (July 2001 to June 2003; n=77 047) and follow-up (June 2004 to February 2006; n=55 021) questionnaire (follow-up response rate=71.4%). After we applied exclusion criteria, our analyses included 48 481 participants (active duty, n=26 613; Reserve or National Guard, n=21 868). Of these, 5510 deployed with combat exposures, 5661 deployed without combat exposures, and 37 310 did not deploy.

Main Outcome Measures

New-onset and continued heavy weekly drinking, binge drinking, and alcohol-related problems at follow-up.

Results

Baseline prevalence of heavy weekly drinking, binge drinking, and alcohol-related problems among Reserve or National Guard personnel who deployed with combat exposures was 9.0%, 53.6%, and 15.2%, respectively; follow-up prevalence was 12.5%, 53.0%, and 11.9%, respectively; and new-onset rates were 8.8%, 25.6%, and 7.1%, respectively. Among active-duty personnel, new-onset rates were 6.0%, 26.6%, and 4.8%, respectively. Reserve and National Guard personnel who deployed and reported combat exposures were significantly more likely to experience new-onset heavy weekly drinking (odds ratio [OR], 1.63; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.36–1.96), binge drinking (OR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.24–1.71), and alcohol-related problems (OR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.33–2.01) compared with nondeployed personnel. The youngest members of the cohort were at highest risk for all alcohol-related outcomes.

Conclusion

Reserve and National Guard personnel and younger service members who deploy with reported combat exposures are at increased risk of new-onset heavy weekly drinking, binge drinking, and alcohol-related problems.

Substance abuse is highly correlated with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other psychological disorders that may occur after stressful and traumatic events, such as those associated with war.1–7 Published studies of military personnel deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan confirm the association between stress related to combat and adverse mental health consequences and report significantly higher rates of PTSD, major depression, and alcohol misuse postdeployment.8–12 Similar findings have been reported among Vietnam13,14 and 1991 Gulf War veterans.15,16 Many of these studies, however, have been limited by the lack of adequate comparison groups for combat veterans and by the inability to control for baseline factors that might influence the association between combat, mental health outcomes, and alcohol misuse.17

Because alcohol use may serve as a coping mechanism after traumatic events, it is plausible that deployment is associated with increased rates of alcohol consumption or problem drinking. It is also possible that depression, PTSD, or stressors related to deployment or return from deployment may make it more difficult to control the effects of alcohol, resulting in greater alcohol-related problems, with or without a commensurate change in weekly drinking. Similarly, baseline overall drinking quantities may remain relatively unchanged while binge drinking increases. The Millennium Cohort Study18 is positioned to prospectively describe alcohol consumption patterns and alcohol-related problems among US service members, many of whom deployed in support of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. The purpose of this exploratory investigation was to determine whether military deployment was associated with new-onset or changes in alcohol consumption, binge drinking behavior, and other alcohol-related problems.

METHODS

Population and Data Sources

The Millennium Cohort Study18 was launched in 2001, with the primary goal of prospectively evaluating the long-term health of military service members and the potential influence of deployment and other military exposures on health. The population-based sample was randomly selected from all US military personnel on rosters as of October 1, 2000. Members of the Reserve and National Guard (Reserve/Guard), women, and those deployed to southwest Asia, Bosnia, or Kosovo between 1998 and 2000 were oversampled to ensure adequate statistical power to detect differences in these smaller subgroups.

This study was approved by the institutional review board at the Naval Health Research Center. A more detailed description of the methodology of this study can be found elsewhere.18

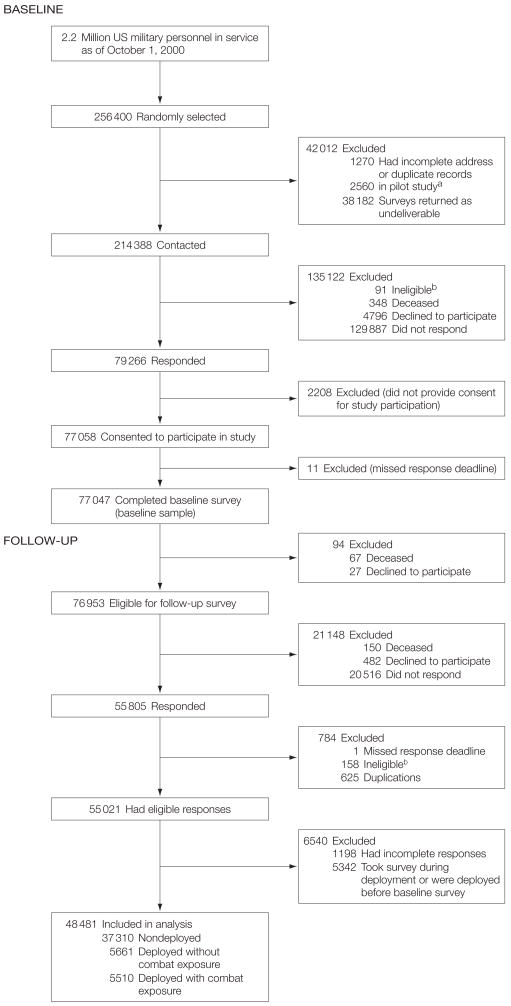

With a modified Dillman approach,19 77 047 of the 256 400 personnel included in the original sample provided informed, voluntary consent and were enrolled in the first panel of the study. Informed consent included acknowledgment of institutional review board-mandated information and the Privacy Act statement. Of the 77 047 participants who completed a baseline survey (2001–2003), 55 021 (71%) completed a follow-up survey (2004–2006). Individuals were excluded from this study if they deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan before the baseline assessment or if they took their survey while deployed because reporting during deployment would likely differ from reporting after deployment. Individuals also were excluded if they did not answer any alcohol outcome questions or were missing demographic or covariate data (Figure).

Figure . Millennium Cohort Study Flow of Participants From Original Sample to Baseline and Follow-up Enrollments to Final Study Population.

aThe 2560 individuals included in the pilot or feasibility study were removed from the mailing list so they would not receive an additional survey.

bIndividuals were considered ineligible if they had an invalid Social Security number, were not serving in the military as of October 1, 2000, or if the survey was filled out by someone other than the invited individual.

For multivariate modeling, including longitudinal data, participants were analyzed in 2 groups. New onset of alcohol outcomes at follow-up was examined among the group with no alcohol outcomes at baseline. Continued alcohol outcomes at follow-up were examined among the group with reported alcohol outcomes at baseline.

Deployment dates were determined with electronic military data. Individuals categorized as deployed in support of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan must have completed their first deployment between baseline and follow-up. Length of deployment was assessed as the cumulative amount of time deployed between baseline and follow-up surveys. This variable was categorized as non-deployed, deployed 1 to 180 days, deployed 181 to 270 days, and deployed greater than 270 days. Combat-related exposures, reported at follow-up, were assessed by affirmative responses to questions that asked whether participants had personally witnessed a person’s death because of war, disaster, or tragic event; witnessed instances of physical abuse; and seen dead or decomposing bodies, maimed soldiers or civilians, or prisoners of war or refugees.

Demographic and military data were obtained from military electronic personnel files and included sex, birth date, race/ethnicity, service branch (Army, Navy, Air Force, Marines), service component (active duty or Reserve/Guard), military pay grade, military occupation, and deployment experience before baseline to southwest Asia, Bosnia, or Kosovo from 1998 to 2000.

Baseline characteristics of the study population were assessed and included in these analyses. History of life stress, which included such items as divorce, experiencing a violent assault, or having a family member die, was assessed by applying scoring mechanisms from the Holmes and Rahe Social Readjustment Rating Scale20,21 to categorize as low/mild, moderate, or severe. Self-reported history of a mental disorder was categorized as those having self-reported symptoms or diagnosis of PTSD only, self-reported symptoms or diagnosis of depression only, and self-reported symptoms or diagnosis of PTSD and depression, and the “other” mental health category was composed of people who self-reported symptoms of other anxiety disorder or panic disorder; self-reported a diagnosis of schizophrenia, psychosis, or manic-depressive disorder; or reported taking medication for anxiety, depression, or stress. PTSD symptoms were measured with the PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version, a 17-item self-report measure of PTSD symptoms that asks respondents to rate the severity of each symptom during the past 30 days on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely).22 Participants were identified as having PTSD symptoms if they reported a moderate or higher level of at least 1 intrusion symptom, 3 avoidance symptoms, and 2 hyperarousal symptoms (criteria established by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition) [DSM-IV]).23 Other anxiety (6 items) and panic (15 items) symptoms were assessed with the Patient Health Questionnaire instrument.24–26 Self-reported depression symptoms (9 items) were assessed with the Patient Health Questionnaire instrument (sensitivity=0.93; specificity=0.89)27 and correspond to the depression diagnosis from the DSM-IV.28

Baseline survey questions were used to identify nonsmokers, past smokers, or current smokers. History of potential alcohol dependence was evaluated with the CAGE29,30 (cut back, annoyed, guilty, eye opener) questions that evaluate whether individuals believed that they needed to cut back on their drinking, felt annoyed at someone who suggested they cut back on drinking, felt guilty about their drinking, or reported needing an eye opener in the morning.

Outcomes

Heavy Weekly Drinking

Heavy weekly drinking, which has shown strong criterion-related validity among military populations in past validation work,31 was estimated at baseline and follow-up by summing the number of drinks reportedly consumed on each day of the week before completing the questionnaire. Heavy drinkers were defined as men who consumed more than 14 drinks per week and women who consumed more than 7 drinks per week, according to research indicating that drinking beyond this level may increase the risk for alcohol-related problems.32–36

Binge Drinking

Binge drinking was estimated at baseline and follow-up by using the number of drinks consumed on each day of the week before taking the questionnaire or the frequency with which participants consumed 5 or more drinks per day or occasion. Binge drinkers were defined as those who reported drinking 5 or more drinks (for men) or 4 or more drinks (for women) on at least 1 day of the week or those who reported “drinking 5 or more alcoholic beverages” on at least 1 day or occasion during the past year.37

Alcohol-Related Problems

Alcohol-related problems were assessed at baseline and follow-up with questions from the Patient Health Questionnaire.24–26 This instrument asked whether any of the following happened more than once in the last 12 months:(a) you drank alcohol even though a physician suggested that you stop drinking because of a problem with your health; (b) you drank alcohol, were high from alcohol, or were hung over while you were working, going to school, or taking care of children or other responsibilities; (c) you were late for or missed work, school, or other activities because you were drinking or hung over; (d) you had a problem getting along with people while you were drinking; and (e) you drove a car after having several drinks or after drinking too much. For this analysis, individuals who endorsed at least 1 item were classified as having an alcohol-related problem.

Statistical Analysis

These analyses were largely exploratory, marking the first investigation of alcohol use in the Millennium Cohort. Univariate analyses including χ2 tests of association were used to investigate unadjusted associations between each alcohol outcome and deployment, occupational, demographic, and behavioral characteristics. Initial analyses were conducted to assess the presence of multicollinearity by using a variance inflation factor of 4 or greater.

Before examination of these data, the variables sex,38,39 birth year,40 race/ethnicity,38,41,42 education,42–44 marital status,45 service branch,46,47 service component,10,48 military pay grade,49 occupation,50 deployment length,51 deployment to a different conflict before baseline,52 history of life stressors,53–55 self-reported symptoms or diagnosis of mental disorders,5,56 smoking status,40,57 and history of potential alcohol dependence58 were considered for analyses according to the literature, and the decision to test for a first-order multiplicative interaction between combat deployment status and service branch was made. Significant associations between reported alcohol measures and independent variables included an investigation of possible confounding while adjusting for all other variables in the model. Variables were considered confounders if they changed the measure of association between alcohol use and deployment by more than 10%.59 Variables that were not significant in the models (P<.05) or were not confounders were removed from the models by using a backward elimination process. Interaction terms were considered significant at P≤.10.

After examination of these data, the covariates sex, birth year, race/ethnicity, service branch, service component, deployment length, history of mental disorders, smoking status, and CAGE/alcohol were found to most influence the relationship of combat deployment and alcohol use and were retained for analyses. Race/ethnicity was included because drinking behaviors and values about alcohol may be tied to racial or cultural values.41 Race and ethnicity were self-designated by personnel on intake forms, with multiple selections permitted, and captured by the Defense Enrollment Eligibility Reporting System (DEERS). We accessed this information from electronic military files that are created with the reporting system data and included a race/ethnicity variable as follows: (1) American Indian/Alaskan native, (2) Asian/Pacific Islander, (3) black, non-Hispanic, (4) white, non-Hispanic, (5) Hispanic, (6) other, and (7) unknown. For the purposes of these analyses, categories were collapsed to black, non-Hispanic, white, non-Hispanic, and other. Because service branch did not significantly modify the relationship between combat deployment and alcohol use and the military experiences of active duty and Reserve/Guard personnel are different, an interaction between combat deployment status and service component was tested and found to be significant. For both active duty and Reserve/Guard populations, separate multivariate logistic regression models were used to compare the adjusted odds of association between deployment to support the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and new-onset and continued heavy drinking, binge drinking, and alcohol-related problems at follow-up, resulting in a total of 12 models. Because of the exploratory nature of these analyses, no statistical adjustments were made for multiple comparisons. Data management and statistical analyses were performed with SAS software (version 9.1; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

Of the 77 047 Millennium Cohort baseline participants, 55 021 completed a follow-up questionnaire and 22 026 were nonresponders. The response rate for the follow-up study was calculated as 71.4% with a standard definition from the American Association for Public Opinion Research.60 For longitudinal data analyses, those with baseline and follow-up data were included. Of these participants, 5342 deployed before taking the baseline survey or took either survey while deployed, 525 were missing alcohol outcome information at baseline or follow-up, and 673 were missing demographic or covariate data, leaving 48 481 individuals for analyses (62.9% of baseline participants).

Participants were further classified into those with and without reported alcohol outcomes at baseline to examine both continued and newly reported alcohol outcomes at follow-up. To ascertain newly reported drinking outcomes, participants reporting alcohol use behavior at baseline were removed from analyses. For analyses of continued alcohol behavior, participants not reporting alcohol outcomes at baseline were removed from analyses.

The demographic characteristics of baseline participants, follow-up participants, and those excluded because of missing baseline or follow-up data are displayed in Table 1. Of the 48 481 study participants, 5510 (11.4%) were deployed with combat exposures, 5661 (11.7%) were deployed without combat exposures, and 37 310 (77.0%) were not deployed. Proportions of individuals followed up were similar across demographic subgroups among those who deployed with and without combat exposure and those who deployed before baseline or took their survey while deployed, except that those who deployed with combat exposures were more likely to report PTSD symptoms at follow-up. Those excluded because of missing baseline or follow-up data were more likely to be younger, black, non-Hispanic or unknown race/ethnicity, Marines, current smokers, and to report PTSD and depression symptoms or diagnosis at baseline.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Millennium Cohort Participants at Baseline and Follow-up by Deployment and Response Status

| No. (%)a | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-up Survey Respondents (n = 48 481) | ||||||

| Characteristic | Baseline Survey Respondents (n = 77 047) | Deployed With Combat Exposures (n = 5510) | Deployed Without Combat Exposures (n = 5661) | Nondeployed (n = 37 310) | Deployed Before Baseline or Took Survey During Deployment (n = 5342) | Excluded Because of Missing Baseline or Follow-up Datab (n = 23 224) |

| Sex Male |

56 415 (73.2) | 4572 (8.1) | 4516 (8.0) | 25 952 (46.0) | 4455 (7.9) | 16 920 (30.0) |

| Female | 20 632 (26.8) | 938 (4.5) | 1145 (5.5) | 11 358 (55.1) | 887 (4.3) | 6304 (30.6) |

| Birth, y Before 1960 |

16 652 (21.6) | 843 (5.1) | 1107 (6.6) | 10 473 (62.9) | 753 (4.5) | 3476 (20.9) |

| 1960–1969 | 29 177 (37.9) | 2200 (7.5) | 2434 (8.3) | 15 029 (51.5) | 2177 (7.5) | 7337 (25.1) |

| 1970–1979 | 26 672 (34.6) | 2136 (8.0) | 1849 (6.9) | 10 479 (39.3) | 2121 (8.0) | 10 087 (37.8) |

| 1980 and later | 4546 (5.9) | 331 (7.3) | 271 (6.0) | 1329 (29.2) | 291 (6.4) | 2324 (51.1) |

| Race/ethnicity White, non-Hispanic |

53 589 (69.6) | 3751 (7.0) | 4200 (7.8) | 26 553 (49.5) | 3719 (6.9) | 15 366 (28.7) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 10 601 (13.8) | 586 (5.5) | 620 (5.8) | 4692 (44.3) | 639 (6.0) | 4064 (38.3) |

| Other | 12 796 (16.6) | 1173 (9.2) | 841 (6.6) | 6065 (47.4) | 983 (7.7) | 3734 (29.2) |

| Unknown | 61 (0.1) | 1 (1.6) | 60 (98.4) | |||

| Service branch Army |

36 481 (47.4) | 3582 (9.8) | 1486 (4.1) | 17 953 (49.2) | 2600 (7.1) | 10 860 (29.8) |

| Air Force | 22 357 (29.0) | 1170 (5.2) | 2980 (13.3) | 10 408 (46.6) | 1682 (7.5) | 6117 (27.4) |

| Navy and Coast Guard | 14 268 (18.5) | 402 (2.8) | 1004 (7.0) | 7435 (52.1) | 909 (6.4) | 4518 (31.7) |

| Marine Corps | 3941 (5.1) | 356 (9.0) | 191 (4.8) | 1514 (38.4) | 151 (3.8) | 1729 (43.9) |

| Service component Active duty |

43 890 (57.0) | 3418 (7.8) | 3457 (7.9) | 19 738 (45.0) | 3645 (8.3) | 13 632 (31.1) |

| Reserve/National Guard | 33 157 (43.0) | 2092 (6.3) | 2204 (6.6) | 17 572 (53.0) | 1697 (5.1) | 9592 (28.9) |

| Cumulative deployment, d Nondeployed |

53 659 (69.6) | 37 310 (69.5) | 16 349 (30.4) | |||

| 1–180 | 8906 (11.6) | 2359 (26.5) | 3843 (43.2) | 2704 (30.4) | ||

| 181–270 | 3881 (5.0) | 1292 (33.3) | 1057 (27.2) | 1532 (39.5) | ||

| >270 | 5259 (6.8) | 1859 (35.3) | 761 (14.5) | 2639 (50.1) | ||

| Otherd | 5342 | |||||

| History of mental disorders None |

67 125 (87.1) | 4920 (7.3) | 5171 (7.7) | 32 324 (48.2) | 4855 (7.2) | 19 855 (29.6) |

| Depression symptoms/diagnosis | 4484 (5.8) | 235 (5.2) | 239 (5.3) | 2388 (53.3) | 232 (5.2) | 1390 (31.0) |

| PTSD symptoms/diagnosis | 1655 (2.2) | 134 (8.1) | 77 (4.7) | 749 (45.3) | 87 (5.3) | 608 (36.7) |

| PTSD and depression symptoms/diagnosis | 2516 (3.3) | 136 (5.4) | 105 (4.2) | 1208 (48.0) | 103 (4.1) | 964 (38.3) |

| Other mental health disorder symptoms or self-reported psychiatric medication use | 1267 (1.6) | 85 (6.7) | 69 (5.4) | 641 (50.6) | 65 (5.1) | 407 (32.1) |

| Smoking status Nonsmoker |

44 312 (57.5) | 3202 (7.2) | 3440 (7.8) | 22 243 (50.2) | 3043 (6.9) | 12 384 (27.9) |

| Past smoker | 18 275 (23.7) | 1271 (7.0) | 1306 (7.1) | 9321 (51.0) | 1222 (6.7) | 5155 (28.2) |

| Current smoker | 13 778 (17.9) | 1037 (7.5) | 915 (6.6) | 5746 (41.7) | 1037 (7.5) | 5043 (36.6) |

| Unknown | 682 (0.9) | 40 (5.9) | 642 (94.1) | |||

| History of potential alcohol dependencec No |

62 789 (81.5) | 4453 (7.1) | 4625 (7.4) | 30 567 (48.7) | 4383 (7.0) | 18 761 (29.9) |

| Yes | 14 258 (18.5) | 1057 (7.4) | 1036 (7.3) | 6743 (47.3) | 959 (6.7) | 4463 (31.3) |

Abbreviation: PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder.

Percentages in the first column were calculated as percentage of total baseline population and may not sum to 100 due to rounding. The percentages in the next 5 columns were calculated with the number in each cell as the numerator and the corresponding baseline number in each characteristic as the denominator.

Of the 23 224 personnel who were excluded because of missing baseline or follow-up data, administrative records indicated that 6875 (30%) completed at least 1 deployment after their baseline survey but before February 14, 2006, the last day that follow-up surveys were accepted. However, information on combat exposure was not available from administrative records and therefore could be assessed only for personnel who responded to the follow-up survey.

Potential alcohol dependence was derived by endorsement of at least 1 item from the CAGE questions at baseline.29,30

Cumulative deployment length was not calculated for the 5342 individuals who were deployed before the baseline assessment or took the survey while deployed and were excluded from the study.

Among active-duty personnel, the baseline, follow-up, and new-onset prevalence of all 3 drinking outcomes was highest among those deployed with combat exposures compared with those deployed without combat exposures and nondeployed personnel (Table 2). Proportionally more women than men reported heavy weekly drinking at baseline and new onset, whereas proportionally more men reported binge drinking and alcohol-related problems at all points. Baseline, follow-up, and new-onset prevalence of all outcomes was highest among those who were younger, white, non-Hispanic, Marines, and current smokers and those with a positive result on the CAGE questionnaire. Among Reserve/Guard personnel, baseline, follow-up, and new-onset prevalence of all outcomes was highest among those who were deployed with combat exposures, were younger, were Marines, had PTSD or PTSD and depression, were current smokers, and had a positive result on the CAGE questionnaire (Table 3).

Table 2.

Prevalence of Baseline, Follow-up, and New-Onset Alcohol Use of Active-Duty Millennium Cohort Participants Reporting Outcomes

| No. (%)a | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heavy Weekly Drinkers | Binge Drinkers | ≥1 Drinking-Related Problem | |||||||

| Characteristic | Baseline (n = 1950) | Follow-up (n = 2037) | New Onset (n = 1185) | Baseline (n = 12 606) | Follow-up (n = 12 323) | New Onset (n = 2836) | Baseline (n = 2516) | Follow-up (n = 1584) | New Onset (n = 889) |

| Deployment status Nondeployed |

1396 (7.3) | 1485 (7.7) | 850 (4.8) | 8828 (44.9) | 8671 (44.1) | 2092 (19.3) | 1820 (9.3) | 1165 (5.9) | 645 (3.6) |

| Deployed without combat exposures | 239 (7.1) | 247 (7.4) | 154 (4.9) | 1811 (52.6) | 1740 (50.6) | 359 (22.0) | 321 (9.3) | 172 (5.0) | 98 (3.2) |

| Deployed with combat exposures | 315 (9.5) | 305 (9.2) | 181 (6.0) | 1967 (57.6) | 1912 (56.0) | 385 (26.6) | 375 (11.0) | 247 (7.2) | 146 (4.8) |

| Sex Male |

1424 (7.4) | 1530 (7.9) | 877 (4.9) | 10 446 (52.8) | 10 221 (51.7) | 2118 (22.7) | 2058 (10.4) | 1291 (6.5) | 706 (4.0) |

| Female | 526 (8.0) | 507 (7.7) | 308 (5.1) | 2160 (32.0) | 2102 (31.1) | 718 (15.6) | 458 (6.8) | 293 (4.4) | 183 (2.9) |

| Birth, y Before 1960 |

222 (5.8) | 272 (7.2) | 133 (3.7) | 1189 (30.6) | 1208 (31.1) | 356 (13.2) | 220 (5.7) | 152 (3.9) | 81 (2.2) |

| 1960–1969 | 628 (5.6) | 749 (6.7) | 450 (4.3) | 4928 (42.8) | 4916 (42.7) | 1260 (19.2) | 757 (6.6) | 442 (3.8) | 271 (2.5) |

| 1970–1979 | 921 (9.4) | 857 (8.8) | 506 (5.7) | 5817 (58.0) | 5476 (54.6) | 1028 (24.4) | 1321 (13.2) | 815 (8.1) | 449 (5.2) |

| 1980 and later | 179 (16.4) | 159 (14.6) | 96 (10.5) | 672 (60.2) | 723 (64.7) | 192 (43.2) | 218 (19.6) | 175 (15.7) | 88 (9.8) |

| Race/ethnicity White, non-Hispanic |

1414 (8.4) | 1506 (9.0) | 865 (5.6) | 8985 (52.4) | 8687 (50.7) | 1809 (22.2) | 1821 (10.6) | 1165 (6.8) | 653 (4.3) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 175 (5.2) | 156 (4.6) | 95 (3.0) | 934 (26.8) | 1023 (29.4) | 387 (15.2) | 227 (6.5) | 140 (4.0) | 80 (2.5) |

| Other | 361 (6.3) | 375 (6.5) | 225 (4.2) | 2687 (45.4) | 2613 (44.2) | 640 (19.8) | 468 (7.9) | 279 (4.7) | 156 (2.9) |

| Service branch Army |

873 (8.5) | 881 (8.6) | 519 (5.5) | 4978 (47.2) | 4910 (46.6) | 1148 (20.6) | 998 (9.5) | 699 (6.6) | 390 (4.1) |

| Air Force | 419 (5.2) | 457 (5.7) | 280 (3.7) | 3567 (43.0) | 3491 (42.1) | 867 (18.4) | 531 (6.4) | 286 (3.5) | 176 (2.3) |

| Navy and Coast Guard | 486 (8.1) | 513 (8.6) | 282 (5.1) | 3087 (50.8) | 2974 (48.9) | 661 (22.1) | 732 (12.0) | 414 (6.8) | 220 (4.1) |

| Marine Corps | 172 (10.8) | 186 (11.7) | 104 (7.3) | 974 (60.1) | 948 (58.5) | 160 (24.8) | 255 (15.7) | 185 (11.4) | 103 (7.6) |

| Cumulative deployment, d Nondeployed |

1396 (7.3) | 1485 (7.7) | 850 (4.8) | 8828 (44.9) | 8671 (44.1) | 2092 (19.3) | 1820 (9.3) | 1165 (5.9) | 645 (3.6) |

| 1–180 | 253 (6.9) | 250 (6.8) | 156 (4.6) | 1981 (52.4) | 1934 (51.1) | 424 (23.5) | 349 (9.3) | 202 (5.4) | 126 (3.7) |

| 181–270 | 141 (9.6) | 140 (9.5) | 77 (5.8) | 885 (58.5) | 841 (55.6) | 163 (26.0) | 174 (11.5) | 104 (6.9) | 62 (4.6) |

| >270 | 160 (10.5) | 162 (10.7) | 102 (7.5) | 912 (58.5) | 877 (56.2) | 157 (24.2) | 173 (11.1) | 113 (7.3) | 56 (4.1) |

| History of mental disorders None |

1591 (7.0) | 1702 (7.5) | 997 (4.7) | 11 063 (47.3) | 10 855 (46.5) | 2465 (20.0) | 1962 (8.4) | 1236 (5.3) | 723 (3.4) |

| Depression symptoms/diagnosis | 128 (9.1) | 136 (9.7) | 81 (6.3) | 664 (46.1) | 636 (44.1) | 177 (22.8) | 220 (15.3) | 132 (9.2) | 71 (5.8) |

| PTSD symptoms/diagnosis | 73 (14.3) | 63 (12.4) | 29 (6.7) | 310 (59.3) | 268 (51.2) | 48 (22.5) | 116 (22.2) | 67 (12.8) | 28 (6.9) |

| PTSD and depression symptoms/diagnosis | 115 (14.7) | 100 (12.8) | 58 (8.7) | 389 (48.4) | 377 (47.0) | 101 (24.4) | 168 (21.0) | 120 (15.0) | 54 (8.5) |

| Other mental health disorder symptoms or self-reported psychiatric medication use | 43 (11.1) | 36 (9.3) | 20 (5.8) | 180 (45.0) | 187 (46.8) | 45 (20.5) | 50 (12.5) | 29 (7.3) | 13 (3.7) |

| Smoking status Nonsmoker |

679 (4.4) | 752 (4.8) | 483 (3.2) | 6207 (38.8) | 6087 (38.1) | 1654 (16.9) | 1015 (6.4) | 638 (4.0) | 399 (2.7) |

| Past smoker | 571 (9.3) | 641 (10.4) | 382 (6.8) | 3485 (55.4) | 3449 (54.8) | 743 (26.5) | 710 (11.3) | 465 (7.4) | 261 (4.7) |

| Current smoker | 700 (16.9) | 644 (15.5) | 320 (9.3) | 2914 (68.5) | 2787 (65.5) | 439 (32.7) | 791 (18.6) | 481 (11.3) | 229 (6.6) |

| History of potential alcohol dependenceb No |

911 (4.3) | 1095 (5.2) | 768 (3.8) | 8890 (40.9) | 8911 (41.0) | 2476 (19.3) | 1091 (5.0) | 776 (3.6) | 568 (2.8) |

| Yes | 1039 (22.1) | 942 (20.0) | 417 (11.4) | 3716 (77.4) | 3412 (71.0) | 360 (33.1) | 1425 (29.6) | 808 (16.8) | 321 (9.5) |

Table 3.

Prevalence of Baseline, Follow-up, and New-Onset Alcohol Use of Reserve/Guard Millennium Cohort Participants Reporting Outcomes

| No. (%)a | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heavy Weekly Drinkers | Binge Drinkers | >1 Drinking-Related Problem | |||||||

| Characteristic | Baseline (n = 1791) | Follow-up (n = 2022) | New Onset (n = 1075) | Baseline (n = 9216) | Follow-up (n = 9291) | New Onset (n = 2264) | Baseline (n = 2736) | Follow-up (n = 1735) | New Onset (n = 776) |

| Deployment status Nondeployed |

1415 (8.3) | 1566 (9.2) | 801 (5.1) | 6997 (39.9) | 7105 (40.6) | 1804 (17.1) | 2099 (12.0) | 1322 (7.6) | 588 (3.8) |

| Deployed without combat exposures | 193 (9.0) | 201 (9.4) | 110 (5.6) | 1100 (50.0) | 1078 (49.0) | 212 (19.3) | 320 (14.6) | 166 (7.6) | 62 (3.3) |

| Deployed with combat exposures | 183 (9.0) | 255 (12.5) | 164 (8.8) | 1119 (53.6) | 1108 (53.0) | 248 (25.6) | 317 (15.2) | 247 (11.9) | 126 (7.1) |

| Sex Male |

1227 (8.3) | 1381 (9.4) | 735 (5.4) | 7279 (48.0) | 7309 (48.2) | 1561 (19.8) | 2142 (14.2) | 1372 (9.1) | 584 (4.5) |

| Female | 564 (8.7) | 641 (9.9) | 340 (5.8) | 1937 (29.1) | 1982 (29.8) | 703 (14.9) | 594 (9.0) | 363 (5.5) | 192 (3.2) |

| Birth, y Before 1960 |

630 (7.6) | 732 (8.9) | 334 (4.4) | 2615 (30.8) | 2683 (31.6) | 742 (12.6) | 711 (8.4) | 454 (5.4) | 214 (2.8) |

| 1960–1969 | 586 (7.4) | 679 (8.6) | 367 (5.0) | 3590 (44.3) | 3649 (45.0) | 928 (20.6) | 953 (11.8) | 590 (7.3) | 269 (3.8) |

| 1970–1979 | 464 (10.8) | 470 (10.9) | 271 (7.1) | 2544 (57.8) | 2430 (55.2) | 450 (24.3) | 886 (20.2) | 554 (12.6) | 227 (6.5) |

| 1980 and later | 111 (14.0) | 141 (17.7) | 103 (15.1) | 467 (57.4) | 529 (65.1) | 144 (41.6) | 186 (23.0) | 137 (16.9) | 66 (10.6) |

| Race/ethnicity White, non-Hispanic |

1539 (9.1) | 1744 (10.4) | 910 (5.9) | 7761 (44.9) | 7738 (44.8) | 1764 (18.5) | 2296 (13.3) | 1420 (8.2) | 614 (4.1) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 115 (5.0) | 117 (5.1) | 66 (3.0) | 547 (22.8) | 633 (26.4) | 265 (14.3) | 167 (7.0) | 129 (5.4) | 70 (3.2) |

| Other | 137 (6.7) | 161 (7.8) | 99 (5.2) | 908 (42.5) | 920 (43.1) | 235 (19.1) | 273 (12.8) | 186 (8.7) | 92 (4.9) |

| Service branch Army |

1114 (9.2) | 1199 (10.0) | 639 (5.8) | 5383 (43.3) | 5480 (44.1) | 1362 (19.3) | 1670 (13.5) | 1108 (8.9) | 497 (4.6) |

| Air Force | 438 (7.2) | 539 (8.9) | 285 (5.1) | 2536 (40.8) | 2531 (40.7) | 594 (16.1) | 665 (10.7) | 381 (6.1) | 173 (3.1) |

| Navy and Coast Guard | 187 (7.0) | 231 (8.7) | 127 (5.1) | 1054 (38.6) | 1044 (38.2) | 269 (16.0) | 303 (11.1) | 178 (6.5) | 79 (3.3) |

| Marine Corps | 52 (12.3) | 53 (12.5) | 24 (6.5) | 243 (56.1) | 236 (54.5) | 39 (20.5) | 98 (22.6) | 68 (15.7) | 27 (8.0) |

| Cumulative deployment, d Nondeployed |

1415 (8.3) | 1566 (9.2) | 801 (5.1) | 6997 (39.9) | 7105 (40.6) | 1804 (17.1) | 2099 (12.0) | 1322 (7.6) | 588 (3.8) |

| 1–180 | 203 (8.7) | 233 (9.9) | 132 (6.2) | 1197 (49.8) | 1184 (49.2) | 244 (20.2) | 323 (13.5) | 194 (8.1) | 88 (4.2) |

| 181–270 | 87 (10.7) | 92 (11.3) | 57 (7.8) | 430 (52.0) | 443 (53.6) | 101 (25.4) | 132 (16.0) | 89 (10.8) | 39 (5.6) |

| >270 | 86 (8.4) | 131 (12.8) | 85 (9.0) | 592 (56.0) | 559 (52.9) | 115 (24.7) | 182 (17.3) | 130 (12.4) | 61 (7.0) |

| History of mental disorders None |

1422 (7.7) | 1691 (9.2) | 926 (5.5) | 7979 (42.2) | 8058 (42.6) | 1937 (17.7) | 2162 (11.5) | 1360 (7.2) | 623 (3.7) |

| Depression symptoms/diagnosis | 164 (11.9) | 153 (11.1) | 67 (5.5) | 548 (38.8) | 564 (39.9) | 162 (18.7) | 253 (17.9) | 158 (11.2) | 65 (5.6) |

| PTSD symptoms/diagnosis | 62 (14.7) | 50 (11.9) | 23 (6.4) | 216 (49.7) | 208 (47.8) | 56 (25.6) | 103 (23.7) | 62 (14.3) | 27 (8.2) |

| PTSD and depression symptoms/diagnosis | 100 (16.2) | 88 (14.2) | 39 (7.5) | 307 (47.7) | 298 (46.4) | 67 (19.9) | 157 (24.5) | 111 (17.3) | 41 (8.5) |

| Other mental health disorder symptoms or self-reported psychiatric medication use | 43 (11.4) | 40 (10.6) | 20 (6.0) | 166 (42.5) | 163 (41.7) | 42 (18.7) | 61 (15.6) | 44 (11.3) | 20 (6.1) |

| Smoking status Nonsmoker |

654 (5.3) | 802 (6.4) | 495 (4.2) | 4562 (35.6) | 4618 (36.0) | 1275 (15.4) | 1200 (9.4) | 794 (6.2) | 382 (3.3) |

| Past smoker | 575 (10.6) | 631 (11.6) | 316 (6.5) | 2637 (47.4) | 2675 (48.1) | 605 (20.7) | 797 (14.3) | 461 (8.3) | 210 (4.4) |

| Current smoker | 562 (16.9) | 589 (17.7) | 264 (9.6) | 2017 (59.0) | 1998 (58.4) | 384 (27.4) | 739 (21.7) | 480 (14.1) | 184 (6.9) |

| History of potential alcohol dependenceb No |

749 (4.3) | 1042 (6.0) | 700 (4.2) | 6240 (35.0) | 6491 (36.4) | 1943 (16.8) | 1250 (7.0) | 864 (4.9) | 515 (3.1) |

| Yes | 1042 (26.7) | 980 (25.1) | 375 (13.1) | 2976 (74.5) | 2800 (70.1) | 321 (31.4) | 1486 (37.1) | 871 (21.8) | 261 (10.4) |

In the model analyses of all 3 alcohol outcomes, the interaction term between deployment and service component was statistically significant (P<.10), whereas the interaction term between deployment and service branch was not, and thus the models were stratified only by active duty and Reserve/Guard status. Cumulative deployment length was collinear with deployment status and was removed from any modeling consideration. After assessing confounding, all covariates remained in the model because of the number of models and the lack of consistency between covariates that were candidates for removal.

Among active-duty personnel, deployment status was associated with binge drinking after adjustment (Table 4). Those deployed with combat exposures were at increased odds of new-onset binge drinking at follow-up (odds ratio [OR]=1.31; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.14–1.49). Women were 1.21 times more likely to report new-onset heavy weekly drinking (95% CI, 1.04–1.39), whereas they were significantly less likely to report new-onset or changes in binge drinking or alcohol-related problems. Those born after 1980 were at 6.72 increased odds of new-onset binge drinking (95% CI, 5.33–8.46) and 4.67 increased odds of new-onset alcohol-related problems (95% CI, 3.36–6.47). Those with PTSD and depression were at increased odds of new-onset and continued alcohol-related problems at follow-up. Current smokers and individuals with a positive CAGE result at baseline were at increased odds for new-onset and continuation of all 3 drinking outcomes.

Table 4.

Adjusted Odds of New-Onset and Continued Alcohol Outcomes Among Active-Duty Millennium Cohort Participants From Baseline to Follow-up

| OR (95% CI)a | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heavy Weekly Drinking (n = 25 901) | Binge Drinking (n = 26 536) | Alcohol-Related Problems (n = 26 519) | ||||

| Characteristic | New Onset at Follow-up (n = 23 951) | Continued at Follow-up (n = 1950) | New Onset at Follow-up (n = 13 930) | Continued at Follow-up (n = 12 606) | New Onset at Follow-up (n = 24 003) | Continued at Follow-up (n = 2516) |

| Deployment status Nondeployed |

1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Deployed without combat exposures | 1.11 (0.92–1.33) | 0.81 (0.60–1.09) | 1.07 (0.94–1.22) | 1.08 (0.95–1.22) | 0.85 (0.68–1.06) | 0.88 (0.66–1.18) |

| Deployed with combat exposures | 1.12 (0.94–1.33) | 0.86 (0.66–1.13) | 1.31 (1.14–1.49) | 1.07 (0.95–1.21) | 1.03 (0.85–1.26) | 0.84 (0.64–1.09) |

| Sex Male |

1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Female | 1.21 (1.04–1.39) | 0.81 (0.65–1.01) | 0.57 (0.52–0.63) | 0.52 (0.47–0.58) | 0.69 (0.58–0.83) | 0.71 (0.55–0.91) |

| Birth, y Before 1960 |

1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 1960–1969 | 1.13 (0.92–1.38) | 0.56 (0.40–0.77) | 1.67 (1.47–1.90) | 1.17 (1.02–1.36) | 1.15 (0.89–1.48) | 0.66 (0.47–0.92) |

| 1970–1979 | 1.39 (1.14–1.70) | 0.37 (0.27–0.51) | 2.55 (2.22–2.92) | 1.41 (1.22–1.63) | 2.40 (1.87–3.07) | 0.84 (0.61–1.16) |

| 1980 and later | 2.41 (1.81–3.22) | 0.34 (0.22–0.52) | 6.72 (5.33–8.46) | 1.79 (1.41–2.27) | 4.67 (3.36–6.47) | 1.45 (0.95–2.20) |

| Race/ethnicity White, non-Hispanic |

1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 0.60 (0.48–0.75) | 0.65 (0.46–0.92) | 0.74 (0.65–0.85) | 0.70 (0.60–0.82) | 0.71 (0.56–0.91) | 1.00 (0.72–1.38) |

| Other | 0.78 (0.66–0.91) | 0.87 (0.68–1.13) | 0.99 (0.88–1.11) | 0.89 (0.80–0.99) | 0.72 (0.59–0.87) | 0.92 (0.72–1.17) |

| Service branchb Army |

1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Air Force | 0.65 (0.55–0.76) | 1.02 (0.79–1.33) | 0.87 (0.78–0.97) | 0.93 (0.83–1.04) | 0.58 (0.48–0.71) | 0.66 (0.50–0.86) |

| Navy and Coast Guard | 0.83 (0.71–0.97) | 1.11 (0.87–1.42) | 1.08 (0.95–1.21) | 0.95 (0.84–1.06) | 0.95 (0.80–1.14) | 0.83 (0.66–1.05) |

| Marine Corps | 1.11 (0.89–1.40) | 1.23 (0.87–1.73) | 1.06 (0.86–1.29) | 1.20 (1.00–1.44) | 1.48 (1.17–1.88) | 0.97 (0.72–1.32) |

| History of mental disordersb None |

1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Depression symptoms/diagnosis | 1.06 (0.83–1.35) | 0.93 (0.63–1.37) | 1.18 (0.98–1.42) | 0.75 (0.63–0.90) | 1.67 (1.28–2.17) | 1.02 (0.73–1.41) |

| PTSD symptoms/diagnosis | 0.95 (0.64–1.40) | 1.02 (0.63–1.66) | 0.93 (0.67–1.31) | 0.64 (0.49–0.82) | 1.43 (0.95–2.14) | 1.14 (0.75–1.72) |

| PTSD and depression symptoms/diagnosis | 1.30 (0.98–1.74) | 0.67 (0.44–1.01) | 1.07 (0.84–1.36) | 0.71 (0.56–0.89) | 2.18 (1.61–2.95) | 1.48 (1.05–2.09) |

| Other mental health disorder symptoms or self-reported psychiatric medication use | 1.05 (0.66–1.67) | 0.64 (0.34–1.23) | 1.07 (0.76–1.51) | 1.18 (0.82–1.71) | 1.06 (0.60–1.88) | 1.21 (0.65–2.25) |

| Smoking statusb Nonsmoker |

1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Past smoker | 1.94 (1.68–2.24) | 1.20 (0.95–1.51) | 1.79 (1.61–1.99) | 1.37 (1.24–1.52) | 1.53 (1.30–1.81) | 1.23 (0.98–1.53) |

| Current smoker | 2.43 (2.08–2.83) | 1.45 (1.16–1.82) | 2.20 (1.92–2.50) | 1.60 (1.43–1.79) | 1.85 (1.55–2.20) | 1.30 (1.05–1.62) |

| History of potential alcohol dependenceb,c No |

1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 2.84 (2.50–3.23) | 1.72 (1.42–2.08) | 2.01 (1.74–2.31) | 1.75 (1.59–1.93) | 3.19 (2.75–3.69) | 2.10 (1.73–2.54) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder.

Odds ratios and associated 95% CIs were adjusted for all other variables in the table.

Characteristic reported at baseline assessment.

Among Reserve/Guard personnel, deployment with combat exposures was associated with increased odds of new onset of all 3 drinking outcomes compared with nondeployed personnel, with heavy weekly drinking (OR=1.63; 95% CI, 1.36–1.96) and alcohol-related problems (OR=1.63; 95% CI, 1.33–2.01) showing the strongest association (Table 5). The subgroups at risk for new-onset and continued alcohol problems were similar to those reported from the active duty models and included younger age, current smoking, and individuals with a positive CAGE result. Additionally, those reporting any mental health symptoms, diagnoses, or medication use were at significantly increased risk for new-onset alcohol-related problems at follow-up.

Table 5.

Adjusted Odds of New-Onset and Continued Alcohol Outcomes Among Reserve/Guard Millennium Cohort Participants From Baseline to Follow-up

| OR (95% CI)a | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heavy Weekly Drinking (n = 21 211) | Binge Drinking (n = 21 812) | Alcohol-Related Problems (n = 21 761) | ||||

| Characteristic | New Onset at Follow-up (n = 19 420) | Continued at Follow-up (n = 1791) | New Onset at Follow-up (n = 12 596) | Continued at Follow-up (n = 9216) | New Onset at Follow-up (n = 19 025) | Continued at Follow-up (n = 2736) |

| Deployment status Nondeployed |

1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Deployed without combat exposures | 1.09 (0.88–1.36) | 0.66 (0.48–0.91) | 1.10 (0.93–1.30) | 1.12 (0.95–1.32) | 0.88 (0.67–1.16) | 0.96 (0.73–1.25) |

| Deployed with combat exposures | 1.63 (1.36–1.96) | 0.97 (0.70–1.34) | 1.46 (1.24–1.71) | 0.95 (0.81–1.11) | 1.63 (1.33–2.01) | 1.11 (0.86–1.43) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Female | 1.22 (1.06–1.41) | 1.24 (1.00–1.55) | 0.62 (0.55–0.68) | 0.49 (0.43–0.55) | 0.66 (0.55–0.79) | 0.65 (0.53–0.81) |

| Birth, y Before 1960 |

1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 1960–1969 | 1.14 (0.98–1.34) | 0.68 (0.54–0.87) | 2.00 (1.80–2.24) | 1.24 (1.10–1.40) | 1.44 (1.19–1.73) | 0.99 (0.80–1.23) |

| 1970–1979 | 1.56 (1.32–1.86) | 0.43 (0.33–0.56) | 2.69 (2.34–3.09) | 1.49 (1.30–1.70) | 2.55 (2.09–3.12) | 1.16 (0.93–1.45) |

| 1980 and later | 3.74 (2.90–4.83) | 0.27 (0.17–0.43) | 6.90 (5.42–8.79) | 2.27 (1.74–2.97) | 4.82 (3.53–6.57) | 1.33 (0.93–1.90) |

| Race/ethnicity White, non-Hispanic |

1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 0.54 (0.42–0.70) | 0.62 (0.42–0.92) | 0.80 (0.69–0.92) | 0.65 (0.54–0.79) | 0.92 (0.71–1.19) | 0.96 (0.68–1.34) |

| Other | 0.89 (0.71–1.10) | 0.72 (0.50–1.04) | 1.04 (0.89–1.22) | 0.96 (0.81–1.13) | 1.29 (1.03–1.63) | 0.95 (0.73–1.25) |

| Service branchb Army |

1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Air Force | 1.00 (0.85–1.17) | 1.31 (1.02–1.67) | 0.91 (0.81–1.02) | 1.03 (0.91–1.16) | 0.85 (0.70–1.03) | 0.85 (0.69–1.05) |

| Navy and Coast Guard | 1.01 (0.82–1.23) | 1.07 (0.77–1.48) | 0.91 (0.78–1.05) | 0.88 (0.76–1.03) | 0.85 (0.66–1.09) | 0.86 (0.65–1.12) |

| Marine Corps | 0.91 (0.59–1.41) | 1.48 (0.83–2.63) | 0.86 (0.59–1.24) | 1.09 (0.78–1.53) | 1.39 (0.91–2.12) | 1.14 (0.74–1.73) |

| History of mental disordersb None |

1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Depression symptoms/diagnosis | 0.82 (0.63–1.07) | 0.74 (0.52–1.04) | 1.09 (0.91–1.32) | 0.88 (0.72–1.08) | 1.56 (1.18–2.05) | 1.15 (0.87–1.53) |

| PTSD symptoms/diagnosis | 0.89 (0.58–1.39) | 0.54 (0.32–0.92) | 1.32 (0.95–1.82) | 0.65 (0.48–0.89) | 1.90 (1.25–2.87) | 0.94 (0.61–1.45) |

| PTSD and depression symptoms/diagnosis | 1.15 (0.81–1.62) | 0.76 (0.50–1.16) | 1.08 (0.81–1.43) | 0.85 (0.65–1.12) | 2.33 (1.66–3.28) | 1.41 (1.01–1.97) |

| Other mental health disorder symptoms or self-reported psychiatric medication use | 0.98 (0.61–1.56) | 0.61 (0.33–1.14) | 1.19 (0.84–1.68) | 0.81 (0.57–1.16) | 1.85 (1.15–2.96) | 1.20 (0.70–2.04) |

| Smoking statusb Nonsmoker |

1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Past smoker | 1.51 (1.30–1.76) | 1.28 (1.01–1.62) | 1.58 (1.41–1.77) | 1.37 (1.21–1.54) | 1.31 (1.10–1.57) | 0.85 (0.70–1.04) |

| Current smoker | 2.16 (1.84–2.54) | 1.79 (1.41–2.28) | 2.13 (1.85–2.44) | 1.49 (1.31–1.70) | 1.88 (1.56–2.27) | 1.21 (1.00–1.47) |

| History of potential alcohol dependenceb,c No |

1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 3.34 (2.91–3.83) | 1.69 (1.38–2.06) | 2.30 (1.98–2.66) | 1.87 (1.67–2.10) | 3.44 (2.93–4.03) | 1.78 (1.51–2.10) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder.

Odds ratios and associated 95% CIs were adjusted for all other variables in the table.

Characteristic reported at baseline assessment.

COMMENT

Alcohol misuse has been among the concerns reported by soldiers returning from deployment,10 yet research to date has not been able to quantify the relationship between alcohol problems and deployment. To our knowledge, this is the first study to prospectively investigate alcohol misuse in relation to deployment using 3 different metrics in a large population-based military cohort of both active-duty and Reserve/Guard personnel by documenting alcohol use patterns before and after deployment related to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. This study found a significantly increased risk for new-onset heavy weekly drinking, binge drinking, and other alcohol-related problems among Reserve/Guard personnel deployed with reported combat exposures compared with nondeployed Reserve/Guard personnel.

Increased alcohol outcomes among Reserve/Guard personnel deployed with combat exposures is concerning in light of increased reliance on Reserve/Guard forces supporting current operational requirements. This finding is consistent with a recently published study of soldiers returning from Iraq, in which endorsement of alcohol problems according to a 2-item alcohol screen in the newly implemented Post-Deployment Health Reassessment was reported to be 11.8% for active duty and 15.0% for Reserve/Guard.10 A study examining the baseline prevalence of mental health in the Millennium Cohort showed that the weighted prevalence of alcohol-related problems, defined as endorsing one of 5 Patient Health Questionnaire measures, was lower in regular active-duty members (11.5%) compared with Reserve/Guard members (14.1%).61 Possible explanations for increased risk for new-onset drinking outcomes in Reserve/Guard members after deployment include inadequate training and preparation of civilian soldiers for the added stresses of combat exposures faced during deployment; increased stress among individuals and their families having to transition between military and civilian occupational settings; military unit cohesiveness; and reduced access to support services, including family services, health and physical fitness programs, and ongoing prevention programs in civilian communities.10,62

Other demographic and military characteristics associated with changes in drinking behavior include younger age, sex, race/ethnicity, and service branch. Increased risk for alcohol problems in younger personnel is not surprising when it is compared with that of other young cohorts and reported high binge-drinking levels.63 Interventions focused on drinking reduction in younger cohorts that have been effective should be considered in young military personnel before, during, and after deployment. Women were significantly more likely to start drinking heavily but less likely to start binge drinking or have alcohol-related problems compared with men, which may be due to women turning to drinking as a coping mechanism, whereas men may have a higher propensity for risk-taking behaviors.64,65 Sex-specific educational programs for interventions to reduce drinking may be considered. Our finding that whites were at increased risk for drinking outcomes compared with blacks or other races is consistent with past research.38,41,42 Active-duty Marines were also found to be at increased odds of continuing to binge drink after deployment, as well as to experience new-onset alcohol-related problems. Marines may represent another group that should be targeted for interventions because the Hoge et al9 study also showed a higher likelihood of alcohol misuse among Marines than Army personnel after deployment.

Individuals with previous mental health or alcohol problems were at significantly increased risk for changes in drinking behavior. Among CAGE/alcohol-positive individuals at baseline, risk for new-onset and continued drinking at follow-up was high for all 3 outcomes, potentially representing vulnerability toward drinking in these individuals. Those with baseline symptoms of depression or PTSD and depression were also at increased risk for new-onset alcohol-related problems in active duty and Reserve/Guard. Among Reserve/Guard, the risk for new-onset alcohol-related problems was significant for those with any report of mental health symptoms or medication use, possibly because of the difficulties of work and family responsibilities that shift quickly. Research has suggested that PTSD is associated with changes in alcohol consumption5 and that alcohol misuse is comorbid with several mental health disorders.56 However, it is difficult to separate any clear causal pathways because the etiology of these disorders is likely intertwined.

Unfortunately, a simple solution to mitigating the effects of these comorbidities among military personnel has yet to be discovered, and research has identified difficulties in reducing stigma and barriers to care.8–10 A recent report showed that although the military has reduced smoking and other drug use, progress remains slow on reduction in heavy drinking.66 Continued screening using such items as the Post-Deployment Health Reassessment, given 3 to 6 months after deployment, will help to identify at-risk individuals who may need to seek treatment. As Milliken et al10 suggested, it is important that the military establish policies endorsing “confidentiality” and “self-referral” for optimal effectiveness. A potentially interesting strategy to aid problem drinkers is self-help, Web-based intervention.67 This method was tested in a controlled trial, showed efficacy in drinking reduction, and could be promising for use among military personnel because of perceived privacy of a Web-based tool. Another potential strategy to reduce drinking involves assessing “drinking motivation type (experimenters, thrill seekers, multireasoners, and relaxers)” and then targeting interventions according to a person’s profile.68 Finally, a technique called the brief negotiated interview, proposed by Fernandez et al,69 uses a “method designed to enhance a patient’s motivation to change, rooted in the principles of motivational interviewing.” This method might be useful for the military in settings in which one-on-one interaction is feasible because development of rapport with the individual is a key to this method.

Our study has several possible limitations. The Millennium Cohort may not be representative of the military as a whole or those who are deployed. However, thorough evaluations of possible biases suggest the cohort is a representative sample of military personnel, as measured by demographic and mental health characteristics and reliable health and exposure reporting.18,61,70–74 Nondeployed individuals may not have deployed because they were unfit owing to health status, which means our comparison group may have been less healthy than our deployed groups, potentially biasing our results toward the null. Another important limitation is that the authors did not collect information on the circumstances under which the participants took the survey. Therefore, the various circumstances under which responses were reported, such as anxiety before war, may have influenced response. However, because both binge drinking and alcohol-related problems were related to behaviors during the past year, the effect of differing circumstances was likely minimal. Additionally, the average amount of time between returning home from deployment and completing the follow-up survey was 1 year, making it difficult to determine both short- and long-term effects of deployment on alcohol use. Self-reported data are subject to recall bias, and the actual number of drinks consumed in the past week may be difficult for participants to easily remember.75,76 Measures of binge drinking also differed slightly between baseline and follow-up assessments. Although the core text of the questions (“5 or more drinks” in 1 day or on 1 occasion) was nearly identical, the response options were presented differently. Another potential limitation is that both questionnaires identify overall alcohol consumption, which has been shown to underestimate actual consumption compared with beverage-specific consumption questions.75 It is also possible that military personnel are less likely to endorse alcohol-related questions because of concern that acknowledging risky behavior could hinder career progression. However, other studies have found that self-reported weekly alcohol consumption measures, even when service members know the survey is not anonymous, demonstrate good criterion-related validity.31 Finally, although we collected data on several known and theoretical confounders, we did not have information on other drug use.

Despite these limitations, our study has important strengths. The Millennium Cohort has the advantage of being systematically drawn from all branches and components of the US military, yielding a large sample size with statistical power to detect meaningful differences among subgroups of this population. Additionally, data on quantity of drinking are strengthened by the use of different metrics (weekly drinking, daily drinking, and alcohol problems) to capture this information. Moreover, these data longitudinally measure heavy drinking, binge drinking, and drinking-related problems, independent of the timing of deployment, providing prospective insight into these outcomes and any relationship to military deployment in a large population-based sample. Further, alcohol use has been suggested as one possible explanation for previously unexplained increases in injury mortality subsequent to deployment.77 Finally, although self-reported alcohol consumption may not be a perfect measure, other epidemiologic studies have found these measurements to be generally reliable.78,79

In conclusion, our study found that combat deployment in support of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan was significantly associated with new-onset heavy weekly drinking, binge drinking, and other alcohol-related problems among Reserve/Guard and younger personnel after return from deployment. These results are the first to prospectively quantify changes in alcohol use in relation to recent combat deployments. Interventions should focus on at-risk groups, including Reserve/Guard personnel, younger individuals, and those with previous or existing mental health disorders. Further prospective analyses using Millennium Cohort data will evaluate timing, duration, and comorbidity of alcohol misuse and other-alcohol related problems, better defining the long-term effect of military combat deployments on these important health outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: The Millennium Cohort Study is funded through the Military Operational Medicine Research Program of the US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command, Fort Detrick, Maryland. This work was partially supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIAAA grant R01-AA13324) and the Department of Defense US Army Medical Research Acquisition Activity (DAMD17-01-0676).

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: None reported.

Millennium Cohort Study Team Members: In addition to the authors, the Millennium Cohort Study Team includes Gregory C. Gray, MD, MPH (College of Public Health, University of Iowa, Iowa City), and James R. Riddle, DVM, MPH (Air Force Research Laboratory, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Dayton, Ohio).

Author Contributions: Ms Jacobson had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Jacobson, Ryan, Hooper, Smith, Amoroso, Boyko, Gackstetter, Wells, Bell. Acquisition of data: Ryan, Smith, Amoroso.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Jacobson, Ryan, Smith, Amoroso, Boyko, Bell.

rafting of the manuscript: Jacobson, Hooper, Smith, Amoroso, Wells, Bell.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Jacobson, Ryan, Hooper, Smith, Amoroso, Boyko, Gackstetter, Bell.

Statistical analysis: Jacobson, Boyko. Obtained funding: Ryan.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Ryan, Smith, Gackstetter, Wells.

Study supervision: Ryan, Smith.

Disclaimer: This work represents report 08-08, supported by the Department of Defense, under work unit No. 60002. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of the Army, Department of the Air Force, Department of Defense, or the US government. This research has been conducted in compliance with all applicable federal regulations governing the protection of human subjects in research (Protocol NHRC.2000.007).

Role of the Sponsor: The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, analysis, or preparation of data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Additional Contributions: We are indebted to the Millennium Cohort Study participants, without whom these analyses would not have been possible. We thank Scott L. Seggerman, BS, MS, and Greg D. Boyd, BA, from the Management Information Division, Defense Manpower Data Center, Seaside, California. Additionally, we thank Gina Creaven, MBA, James Davies, BS, Skye Endara, MPH, Lacy Farnell, BS, Gia Gumbs, MPH, Molly Kelton, MS, Cynthia LeardMann, MPH, Travis Leleu, BS, Jamie McGrew, Robert Reed, MS, Besa Smith, MPH, PhD, Katherine Snell, Steven Spiegel, Kari Welch, MA, Martin White, MPH, James Whitmer, Charlene Wong, MPH, and Lauren Zimmermann, MPH, from the Department of Defense Center for Deployment Health Research, Naval Health Research Center, San Diego, California; and Michelle Stoia, BA, also from the Naval Health Research Center. We also thank the professionals from the US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command, especially those from the Military Operational Medicine Research Program, Fort Detrick, Maryland. We appreciate the support of the Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Rockville, Maryland. These individuals provided assistance as part of their official duties as employees of the Department of Defense and none received additional financial compensation.

References

- 1.Schuckit MA, Smith TL, Chacko Y. Evaluation of a depression-related model of alcohol problems in 430 probands from the San Diego prospective study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;82(3):194–203. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kozaric-Kovacic D, Ljubin T, Grappe M. Comorbidity of posttraumatic stress disorder and alcohol dependence in displaced persons. Croat Med J. 2000;41(2):173–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shipherd JC, Stafford J, Tanner LR. Predicting alcohol and drug abuse in Persian Gulf War veterans: what role do PTSD symptoms play? Addict Behav. 2005;30(3):595–599. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chilcoat HD, Breslau N. Investigations of causal pathways between PTSD and drug use disorders. Addict Behav. 1998;23(6):827–840. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McFarlane AC. Epidemiological evidence about the relationship between PTSD and alcohol abuse: the nature of the association. Addict Behav. 1998;23 (6):813–825. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00098-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ross HE. DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence and psychiatric comorbidity in Ontario: results from the Mental Health Supplement to the Ontario Health Survey. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1995;39 (2):111–128. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01150-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swendsen JD, Merikangas KR, Canino GJ, et al. The comorbidity of alcoholism with anxiety and depressive disorders in four geographic communities. Compr Psychiatry. 1998;39(4):176–184. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(98)90058-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoge CW, Auchterlonie JL, Milliken CS. Mental health problems, use of mental health services, and attrition from military service after returning from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. JAMA. 2006;295(9):1023–1032. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.9.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, et al. Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(1):13–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Milliken CS, Auchterlonie JL, Hoge CW. Longitudinal assessment of mental health problems among active and reserve component soldiers returning from the Iraq war. JAMA. 2007;298(18):2141–2148. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.18.2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith TC, Ryan MA, Wingard DL, et al. New onset and persistent symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder self reported after deployment and combat exposures: prospective population based US military cohort study. BMJ. 2008;336(7640):366–371. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39430.638241.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith TC, Wingard DL, Ryan MA, et al. Prior assault and posttraumatic stress disorder after combat deployment. Epidemiology. 2008;19(3):505–512. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31816a9dff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldberg J, Eisen SA, True WR, Henderson WG. A twin study of the effects of the Vietnam conflict on alcohol drinking patterns. Am J Public Health. 1990;80(5):570–574. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.5.570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richards MS, Goldberg J, Rodin MB, Anderson RJ. Alcohol consumption and problem drinking in white male veterans and nonveterans. Am J Public Health. 1989;79(8):1011–1015. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.8.1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Self-reported illness and health status among Gulf War veterans: a population-based study. JAMA. 1997;277(3):238–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Engel CC, Jr, Ursano R, Magruder C, et al. Psychological conditions diagnosed among veterans seeking Department of Defense care for Gulf War-related health concerns. J Occup Environ Med. 1999;41 (5):384–392. doi: 10.1097/00043764-199905000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McLeod DS, Koenen KC, Meyer JM, et al. Genetic and environmental influences on the relationship among combat exposure, posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, and alcohol use. J Trauma Stress. 2001;14(2):259–275. doi: 10.1023/A:1011157800050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ryan MA, Smith TC, Smith B, et al. Millennium Cohort: enrollment begins a 21-year contribution to understanding the impact of military service. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(2):181–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dillman DA. Mail and Telephone Surveys: The Total Design Method. xvi. New York, NY: Wiley; 1978. p. 325. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holmes TH, Rahe RH. The Social Readjustment Rating Scale. J Psychosom Res. 1967;11(2):213–218. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(67)90010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hobson CJ, Kamen J, Szostek J, et al. Stressful life events: a revision and update of the Social Readjustment Rating Scale. Int J Stress Manag. 1998;5 (1):1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weathers FW, Litz BT, Herman DS, et al. The PTSD Checklist (PCL): reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies; October 1993; San Antonio, Texas. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Kroenke K, et al. Utility of a new procedure for diagnosing mental disorders in primary care: the PRIME-MD 1000 Study. JAMA. 1994;272(22):1749–1756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ Primary Care Study: Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. JAMA. 1999;282(18):1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Kroenke K, et al. Validity and utility of the PRIME-MD patient health questionnaire in assessment of 3000 obstetric-gynecologic patients: the PRIME-MD Patient Health Questionnaire Obstetrics-Gynecology Study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183(3):759–769. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.106580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fann JR, Bombardier CH, Dikmen S, et al. Validity of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 in assessing depression following traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2005;20(6):501–511. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200511000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dhalla S, Kopec JA. The CAGE questionnaire for alcohol misuse: a review of reliability and validity studies. Clin Invest Med. 2007;30(1):33–41. doi: 10.25011/cim.v30i1.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ewing JA. Detecting alcoholism: the CAGE questionnaire. JAMA. 1984;252(14):1905–1907. doi: 10.1001/jama.252.14.1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bell NS, Williams JO, Senier L, et al. The reliability and validity of the self-reported drinking measures in the Army’s Health Risk Appraisal survey. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27(5):826–834. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000067978.27660.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.US Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2005. 6. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dawson DA, Grant BF, Li TK. Quantifying the risks associated with exceeding recommended drinking limits. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29(5):902–908. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000164544.45746.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldberg IJ, Mosca L, Piano MR, Fisher EA. AHA Science Advisory: wine and your heart: a science advisory for healthcare professionals from the Nutrition Committee, Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, and Council on Cardiovascular Nursing of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2001;103(3):472–475. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.3.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Criqui MH. Do known cardiovascular risk factors mediate the effect of alcohol on cardiovascular disease? Novartis Found Symp. 1998;216:159–167. doi: 10.1002/9780470515549.ch10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thun MJ, Peto R, Lopez AD, et al. Alcohol consumption and mortality among middle-aged and elderly US adults. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(24):1705–1714. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199712113372401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Naimi TS, Brewer RD, Mokdad A, et al. Binge drinking among US adults. JAMA. 2003;289(1):70–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Costanzo PR, Malone PS, Belsky D, et al. Longitudinal differences in alcohol use in early adulthood. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2007;68(5):727–737. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lande RG, Marin BA, Chang AS, Lande GR. Gender differences and alcohol use in the US Army. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2007;107(9):401–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bray RM, Marsden ME, Peterson MR. Standardized comparisons of the use of alcohol, drugs, and cigarettes among military personnel and civilians. Am J Public Health. 1991;81(7):865–869. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.7.865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dawson DA. Beyond black, white and Hispanic: race, ethnic origin and drinking patterns in the United States. J Subst Abuse. 1998;10(4):321–339. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(99)00009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gilman SE, Breslau J, Conron KJ, et al. Education and race-ethnicity differences in the lifetime risk of alcohol dependence. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62(3):224–230. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.059022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Crum RM, Anthony JC. Educational level and risk for alcohol abuse and dependence: differences by race-ethnicity. Ethn Dis. 2000;10(1):39–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Crum RM, Bucholz KK, Helzer JE, Anthony JC. The risk of alcohol abuse and dependence in adulthood: the association with educational level. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135(9):989–999. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Chou PS. Maturing out of alcohol dependence: the impact of transitional life events. J Stud Alcohol. 2006;67(2):195–203. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ames GM, Cunradi CB, Moore RS, Stern P. Military culture and drinking behavior among US Navy careerists. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2007;68(3):336–344. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Micklewright S. Problem drinking in the Naval Service: a study of personnel identified as alcohol abusers. J R Nav Med Serv. 1996;82(1):34–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vander Weg MW, DeBon M, Sherrill-Mittleman D, et al. Binge drinking, drinking and driving, and riding with a driver who had been drinking heavily among Air National Guard and Air Force Reserve Personnel. Mil Med. 2006;171(2):177–183. doi: 10.7205/milmed.171.2.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Williams JO, Bell NS, Amoroso PJ. Drinking and other risk taking behaviors of enlisted male soldiers in the US Army. Work. 2002;18(2):141–150. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cunradi CB, Moore RS, Ames G. Contribution of occupational factors to current smoking among active-duty US Navy careerists. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(3):429–437. doi: 10.1080/14622200801889002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rona RJ, Fear NT, Hull L, et al. Mental health consequences of overstretch in the UK armed forces. BMJ. 2007;335(7620):603. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39274.585752.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Killgore WD, Cotting DI, Thomas JL, et al. Post-combat invincibility: violent combat experiences are associated with increased risk-taking propensity following deployment. J Psychiatr Res. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shepherd J, Irish M, Scully C, Leslie I. Alcohol consumption among victims of violence and among comparable UK populations. Br J Addict. 1989;84(9):1045–1051. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb00787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ullman SE, Filipas HH, Townsend SM, Starzynski LL. Trauma exposure, posttraumatic stress disorder and problem drinking in sexual assault survivors. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66(5):610–619. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ullman SE, Filipas HH, Townsend SM, Starzynski LL. Correlates of comorbid PTSD and drinking problems among sexual assault survivors. Addict Behav. 2006;31(1):128–132. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Ogburn E, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(7):830–842. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.7.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Agrawal A, Sartor C, Pergadia ML, Huizink AC, Lynskey MT. Correlates of smoking cessation in a nationally representative sample of US adults. Addict Behav. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.04.003. 1016/j.addbeh.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Werner MJ, Walker LS, Greene JW. Concurrent and prospective screening for problem drinking among college students. J Adolesc Health. 1996;18(4):276–285. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(95)00207-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Maldonado G, Greenland S. Simulation study of confounder-selection strategies. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;138(11):923–936. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. 4. Lenexa, KS: American Association for Public Opinion Research; 2006. [Accessed May 28, 2008]. http://www.aapor.org/uploads/standarddefs_4.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Riddle JR, Smith TC, Smith B, et al. Millennium Cohort: the 2001–2003 baseline prevalence of mental disorders in the US military. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(2):192–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wynd CA, Ryan-Wenger NA. The health and physical readiness of Army reservists: a current review of the literature and significant research questions. Mil Med. 1998;163(5):283–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.White AM, Kraus CL, Swartzwelder H. Many college freshmen drink at levels far beyond the binge threshold. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30(6):1006–1010. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Almeida-Filho N, Lessa I, Magalh es L, et al. Alcohol drinking patterns by gender, ethnicity, and social class in Bahia, Brazil. Rev Saude Publica. 2004;38(1):45–54. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102004000100007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hussong AM. Predictors of drinking immediacy following daily sadness: an application of survival analysis to experience sampling data. Addict Behav. 2007;32(5):1054–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bray RM, Hourani LL. Substance use trends among active duty military personnel: findings from the United States Department of Defense Health Related Behavior Surveys, 1980–2005. Addiction. 2007;102(7):1092–1101. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Riper H, Kramer J, Smit F, et al. Web-based self-help for problem drinkers: a pragmatic randomized trial. Addiction. 2008;103(2):218–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Coffman DL, Patrick ME, Palen LA, et al. Why do high school seniors drink? implications for a targeted approach to intervention. Prev Sci. 2007;8(4):241–248. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0078-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fernandez WG, Hartman R, Olshaker J. Brief interventions to reduce harmful alcohol use among military personnel: lessons learned from the civilian experience. Mil Med. 2006;171(6):538–543. doi: 10.7205/milmed.171.6.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.LeardMann CA, Smith B, Smith TC, et al. Smallpox vaccination: comparison of self-reported and electronic vaccine records in the Millennium Cohort Study. Hum Vaccin. 2007;3(6):245–251. doi: 10.4161/hv.4589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Smith B, Leard CA, Smith TC, et al. Anthrax vaccination in the Millennium Cohort: validation and measures of health. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(4):347–353. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Smith B, Smith TC, Gray GC, Ryan MA. When epidemiology meets the Internet: Web-based surveys in the Millennium Cohort Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166(11):1345–1354. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Smith TC, Jacobson IG, Smith B, Hooper TI, Ryan MA. The occupational role of women in military service: validation of occupation and prevalence of exposures in the Millennium Cohort Study. Int J Environ Health Res. 2007;17(4):271–284. doi: 10.1080/09603120701372243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Smith TC, Smith B, Jacobson IG, Corbeil TE, Ryan MA. Reliability of standard health assessment instruments in a large, population-based cohort study. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17(7):525–532. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dawson DA. Methodological issues in measuring alcohol use. Alcohol Res Health. 2003;27(1):18–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Heeb JL, Gmel G. Measuring alcohol consumption: a comparison of graduated frequency, quantity frequency, and weekly recall diary methods in a general population survey. Addict Behav. 2005;30 (3):403–413. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bell NS, Amoroso PJ, Wegman DH, Senier L. Proposed explanations for excess injury among veterans of the Persian Gulf War and a call for greater attention from policymakers and researchers. Inj Prev. 2001;7(1):4–9. doi: 10.1136/ip.7.1.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Carlsson S, Hammar N, Hakala P, et al. Assessment of alcohol consumption by mailed questionnaire in epidemiological studies: evaluation of mis-classification using a dietary history interview and biochemical markers. Eur J Epidemiol. 2003;18 (6):493–501. doi: 10.1023/a:1024694816036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Williams GD, Aitken SS, Malin H. Reliability of self-reported alcohol consumption in a general population survey. J Stud Alcohol. 1985;46(3):223–227. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1985.46.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]