Abstract

The purpose of this study was to determine if chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) is associated with reduced blood flow and muscle oxidative metabolism. Patients with CFS according to CDC criteria (n=19) were compared to normal sedentary subjects (n = 11). Muscle blood flow was measured in the femoral artery with Doppler ultrasound after exercise. Muscle metabolism was measured in the medial gastrocnemius muscle using 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS). Muscle oxygen saturation and blood volume were measured using near-infrared spectroscopy. CFS and controls were not different in hyperemic blood flow or phosphocreatine recovery rate. Cuff pressures of 50,60,70,80,and 90 mmHg were used to partially restrict blood flow during recovery. All pressures reduced blood flow and oxidative metabolism, with 90 mmHg reducing blood flow by 46% and oxidative metabolism by 30.7% in CFS patients. Hyperemic blood flow during partial cuff occlusion was significantly reduced in CFS patients (P < 0.01), and recovery of oxygen saturation was slower (P < 0.05). No differences were seen in the amount of reduction in metabolism with partially reduced blood flow. In conclusion, CFS patients showed evidence of reduced hyperemic flow and reduced oxygen delivery, but no evidence that this impaired muscle metabolism. Thus, CFS patients might have altered control of blood flow, but this is unlikely to influence muscle metabolism. Further, abnormalities in muscle metabolism do not appear to be responsible for the CFS symptoms.

Keywords: oxidative metabolism, exercise, reactive hyperemia, magnetic resonance spectroscopy, near-infrared spectroscopy, Doppler ultrasound, NIRS, oxygen saturation, 31-P MRS, NMR

INTRODUCTION

Patients diagnosed with chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) report significantly reduced activity levels and increased fatigue without a clear medical explanation (11). A number of studies have examined the question of whether CFS is associated with skeletal muscle dysfunction. These studies have provided mixed results, with some finding CFS patients to have lower maximal oxygen consumption (8), reduced muscle strength (12), and abnormal muscle metabolism (1, 2, 13, 41), while other did not (14, 18, 33). Even taking into account differences in methods and in patient populations, it is difficult to interpret the differences between studies.

In two previous studies, we have found muscle oxidative metabolism and muscle oxygen delivery to be reduced in patients with CFS (23, 24). These differences could be the result of metabolic changes due to deconditioning in the CFS patients (40), who are generally reported to be less active than even inactive control subjects (39). But because only 24% of CFS patients were determined to be considerably less active than controls (39), other explanations are needed besides deconditioning. It is also possible that the differences in oxygen delivery could be a result of abnormal autonomic nervous system activity. Sympathetic and parasympathetic tone has been reported to be abnormal in CFS patients (7, 10, 30, 43). Previous studies have suggested that abnormal autonomic nervous system function may lead to reduced blood flow to active muscles, and result in reduced muscle metabolism and exercise performance (26). In support of this idea, several studies have reported that patients with fibromyaglia (a related syndrome) have abnormal muscle blood flow (20).

The aim of this study was to measure blood flow in patients with CFS, and in particular try to determine if reduced blood flow in CFS patients could be responsible for reduced oxidative metabolism we have seen in our previous studies. To test the hypothesis that blood flow is reduced in CFS, we measured the peak hyperemic flow response after short bouts of intense exercise. To test if reduced blood flow is responsible for reduced oxidative metabolism in CFS, we partially restricted blood flow during recovery from exercise and measured the degree to which oxidative metabolism was limited. That is, patients with CFS would have lower peak blood flow values, and would show greater reductions in oxidative metabolism for a given level of flow restriction.

METHODS

Subject selection

CFS patients were diagnosed based on the case definition of CFS (11). Thus, they all reported new onset of fatigue lasting at least 6 months, not relieved by sleep, and producing a substantial decrease of activity in either social, personal or occupational spheres. In addition, patients reported problems lasting at least 6 months in at least 4 of the following symptoms: lymphadenopathy, headaches, myalgia, arthralgia, unrefreshing sleep, cognitive problems, sore throat, or the report that even minor effort produced an exacerbation of their symptom complex. Common medical causes of fatigue were ruled out by blood tests(34), and no patient had the following psychiatric exclusions: manic-depression; schizophrenia; drug/alcohol abuse within 2 years of intake. In addition, we excluded patients who had any psychiatric diagnosis occurring in the 5 years prior to onset of CFS; patients with psychiatric illness beginning after their CFS -- most often depression and/or anxiety -- were excluded. Nineteen CFS patients were tested in this study (age = 39.4 ± 5.4 yrs, 12 females, 7 males). Control subjects were healthy and were chosen to be similar in age and to have a sedentary lifestyle by self-report (regular exercise less than once a week for at least 6 months prior to testing). Eleven control subjects were tested (age = 37.2 ± 6.9 yrs, 5 females and 6 males). The subjects in this study were also used in a companion study (25). This study was approved by the University Committee on Studies Involving Human Beings at the University of Georgia, the New Jersey Medical School, and the University of Pennsylvania.

Experimental protocol

Two sets of experiments were performed, one using MRS and one using Doppler ultrasound. MRS experiments measured the rate of PCr recovery as an index of the capacity of oxidative metabolism (21, 31, 38). High intensity exercise (fast repetition, low load) was used to recruit as much of the muscle as possible, and short durations were used to minimize the development of acidosis, which influences PCr levels(23, 38, 42). Seven exercise bouts were performed by one leg. During all exercises, a blood pressure cuff placed proximal to the knee was inflated to 100 mm Hg above systolic pressure 10 seconds before, during, and for approximately 10 seconds after exercise. This was done to decrease the likelihood of stored oxygen in the muscle at the start of recovery. Previous studies have reported that metabolic recovery from exercise does not occur when the muscle is ischemic (5, 17, 23). Recovery from the first and last exercise bouts occurred with complete release of cuff pressure. The middle five exercise bouts had cuff pressures during recovery that varied from 50,60,70,80,90 mm Hg (one case 40,50,60,70,80 mm Hg). The same seven exercise bouts were also performed on the same leg and blood flow measured in the femoral artery using Doppler ultrasound. In addition, oxygen saturation and blood volume was measured in the medial gastrocnemius using near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS). The order of the MRS and Doppler experiments varied, with approximately one hour between test sessions. The order of the MRS and Doppler tests did not influence the results. The order of the cuff pressures was usually from 50 to 90, but in some subjects the order was reversed. Again, no order effect was seen in the results.

Magnetic resonance spectroscopy

Phosphorus metabolites were measured with a home-built spectrometer system in a 78 cm clear bore, 2.1 Tesla magnet (23, 24). A 6 × 8 cm surface coil tuned to both 31P and 1H frequencies (34.86 and 86.12 MHz respectively) was placed on the medial gastrocnemius muscle. Phosphorus spectra (3000 Hz sweep width, 1024 points) were collected using pulses to produce maximal signal intensity per pulse. Pulse repetition time was 4 seconds and nuclear Overhauser Enhancement (NOE) was used to enhance the 31P signal. Spectra were Fourier transformed with 5 Hz line broadening and integrated in the frequency domain. Areas of the Pi, PCr, and B-ATP peaks were computer integrated and corrections made for differences in saturation and NOE between the peaks. Muscle pH was calculated from the frequency difference between Pi and PCr.

In this study, PCr values during recovery were fit to a single exponential equation to determine a time constant (PCrTc). Maximal muscle oxidative capacity (Vmax) was calculated as the inverse of the time constant * resting PCr concentrations. (23, 24).

Doppler ultrasound

Blood flow was measured in the common femoral artery using quantitative Doppler ultrasound (GE LogiQ 400CL) (27). A linear array transducer was used at a frequency of either 6 or 4 MHz. The imaging site was located on the upper third of the thigh and was proximal to the blood pressure cuff and to the exercising muscle. Resting diameter was measured in the longitudinal view during diastole. Pulsed Doppler ultrasound was recorded in the longitudinal view using an insonation angle less than or equal to 60°. The velocity gate was set to include the entire arterial diameter. Approximately 20 measurements were made over the course of each trial to capture the peak velocity response as well as the general shape of the blood flow response. Values were averaged over two heartbeats. All data were saved to magnetic optical disks for storage and analysis.

Doppler waveforms were analyzed to determine maximum (Vmax) and minimum (Vmin) velocity, and the time average mean velocity (Tmean). All velocity calculations were done by GE's advanced vascular program software for the LogiQ 400 CL. Waveforms that were not automatically measured by the computer were manually traced to determine velocities and flows. B mode images were marked and measured to determine the diameter throughout the test.

Blood flow values were calculated as the product of the time average mean velocity and the vessel cross-sectional area determined from the diameter. For comparisons between CFS and controls, blood flow was calculated two ways: as the highest flow value (peak blood flow) during each hyperemic condition and for the partial cuff experiments as the integrated flow value over the first 60 seconds of recovery. Because blood flow was restricted to the exercising muscle, the peak flow response occurred shortly after release of the cuff pressure after exercise had stopped. The half time to recovery was determined as the time where blood flow dropped to one half the magnitude between maximum flow and resting flow values.

Leg Volume

Leg volume measurements were done by measurements of fat thickness by Doppler ultrasound and by circumference measurements of the lower leg. Doppler images of the thickness between skin to muscle fascia were attained every three centimeters over the medial gastrocnemius and over the anterior tibialis. Total area of the leg was determined from the circumference measured and fat thickness. Based on this information fat volume, lean area volume, and total volume was calculated (28).

Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS)

NIRS measurements used a continuous light source, dual wavelength spectrophotometer (Runman™) (22). The separation distance between the light sources and detectors was 3 cm. Light photons migrate through the tissue and are collected by the detectors with optical filters set at 760 and 850 nm light. The difference signal between 760 and 850 nm was used to indicate changes in oxygen saturation. Voltage signals were digitized into a computer with a commercial AD device (Fluke Databucket).

Exercise

Subjects were placed in the supine position with their knees fully extended. The foot was placed in pedal appratus attached to an air pressure ergometer. Exercise intensity was modulated by changing air pressure in the ergometer. Velcro straps were used to secure the subject to the foot pedal and the platform. Exercise consisted of rapid plantar flexions at a rate of approximately 2 Hz for 10-16 seconds. The pressure was chosen to allow the subject to perform the plantar flexions at the desired rate. Exercise bouts were separated by 8-11 minutes of rest.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means ± SD. Comparison of baseline data between CFS and normals used two-tailed unpaired t-tests for values that were not different between males and females. For comparisons between CFS and control subjects during the partial cuff experiments, ANOVA with group and condition was used. For values that were different between males and females, ANOVA with group (CFS and controls) and sex was used. Significant differences were assumed with p < 0.05.

RESULTS

All of the subjects performed the tests without incident, and we obtained complete data on all 30 subjects. Two potential CFS subjects were tested but were later excluded from the analysis as having either idopathic fatigue or medically explained fatigue. Including or removing these subjects from the analysis did not alter any of the statistical conclusions of the study. Some but not all of the CFS patients reported the testing protocol as tiring. No differences were found between CFS and control subjects in age, height, weight, resting blood pressures, resting heart rates, and lean leg volume (Table 1).

Table 1.

Subject demographics

| Age | Height | Weight | BMI | gender | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| years | meters | kg | kg/m2 | f/m | ||

| CFS | mean | 38.9 | 1.70 | 73.4 | 25.4 | 14/7 |

| SD | 5.4 | 0.10 | 10.9 | 4.0 | ||

| Control | mean | 37.2 | 1.72 | 76.2 | 25.4 | 5/6 |

| SD | 6.9 | 0.10 | 16.9 | 3.4 |

Blood flow

Resting blood velocities or resting femoral artery diameters were not different between CFS and control subjects (Table 2). As lean leg volume and resting blood pressure was not different between CFS and controls, we also found no differences in resting blood flow normalized per lean tissue mass or in resting conductance.

Table 2.

Blood pressure and leg size

| Blood pressure | Leg Volume | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systolic | Diastolic | Mean | Heart rate | Lean | Fat | Total | ||

| mmHg | mmHg | mmHg | bpm | cm3 | cm3 | cm3 | ||

| CFS | mean | 119.1 | 71.7 | 88.2 | 70.2 | 1784 | 891 | 2675 |

| SD | 10.5 | 9.1 | 8.7 | 11.7 | 387 | 352 | 584 | |

| Control | mean | 118.5 | 69.0 | 87.0 | 71.4 | 2003 | 777 | 2781 |

| SD | 11.7 | 9.4 | 10.9 | 10.1 | 511 | 349 | 714 | |

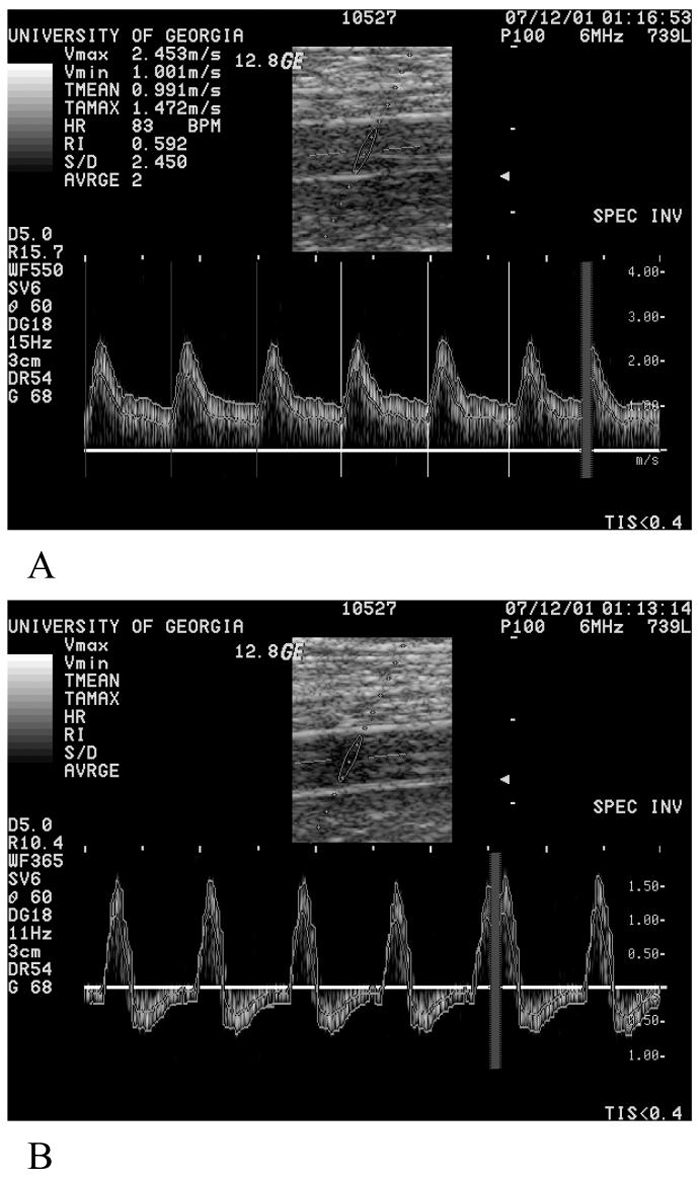

Peak flow responses to exercise usually occurred approximately 10 seconds after release of the cuff. Representative examples of femoral artery blood velocities are shown in Figure 1A. There were no differences in peak blood flow between CFS and control subjects (P = 0.095)(Figure 2A). However, CFS patients did have significantly longer 1/2 times of recovery of oxygen saturation compared to controls subjects (p = 0.024)(Figure 2B). Partial cuff inflation resulted in a reduction in peak blood flow with unusual flow patterns after the first 40-60 seconds (Figure 1B). Figure 3 shows an example of a change in blood flow after exercise with partial cuff inflation. This integrated blood flow over the first 60 seconds of recovery showed a progressive decline with increasing cuff pressure (Figure 4A). As demonstrated in Figure 3, after final release of the cuff, there was an additional bolus of blood flow that was proportional to cuff occlusion pressure (Figure 4B). CFS patients had significantly lower integrated blood flows across all the partial cuff pressures compared to control subjects (P < 0.001). The peak flow responses after partial cuff pressures were not different between groups (P = 0.26). There were no differences in the in the bolus increase in flow after release of occlusion pressure.

Figure 1.

A. Blood velocity patterns 7 seconds after exercise with the cuff deflated to 0 mm Hg. This was the peak flow response for this subject. B. Blood velocity patterns 254 seconds after exercise with the cuff inflated to 90 mm Hg. Velocity data was traced by hand from the lines picked on the machine. Vmax = 1.57 m/s, Vmin = -0.68 m/s, TMEAN = 3.9 cm/s and TAMAX = 3.6 cm/s.

Figure 2.

A Maximal blood flow after exercise with no cuff occlusion in CFS and control subjects. No differences were seen between the first and last tests, or between CFS and controls. B. Recovery of oxygen saturation (O2 recovery T1/2) measured with NIRS in CFS and control subjects. CFS subjects had significantly slower rates of recovery of oxygen saturation. Values are means and SD.

Figure 3.

Typical results for blood flow during the partial cuff experiments. Exercise was proceeded by 10 seconds of cuff ischemia, 12 seconds of exercise was performed during cuff ischemia, and exercise stopped while the cuff ischemia was maintained for an additional 10 seconds, and then the cuff was released. For clarity, the results 3 of the 7 experiments are shown. Note the exercise hyperemic effect was slightly reduced with the application of 60 and 90 mmHg occlusion. After release of the cuff, an additional hyperemic effect was observed.

Figure 4.

Summary of blood flow responses to partial cuff occlusion for CFS and control subjects. A. Integrated flow responses for the first 60 seconds after exercise and during partial cuff inflation. CFS subjects had significantly lower integrated blood flow values compared to control subjects. B. Peak flow responses after complete release of the cuff following partial cuff inflation. Note that increasing partial cuff pressure resulted in increasing peak flow responses. No differences were seen between CFS and control subjects. Values are means and SD.

Oxidative metabolism

In response to the short exercise bouts, PCr levels were on average, 54% of resting for CFS patients and 50% of resting for controls. Representative examples of changes in PCr during the exercise bouts are shown in Figure 5. End exercise pH was not different between groups (6.97 ± 0.08 for CFS and 6.97 ± 0.09 for controls). This resulted in end exercise ADP levels that were not significantly different between groups (Figure 6). The time constant of PCr recovery (PCrTc) after exercise was not different between CFS and control subjects (40.6 ± 12.6 s for CFS and 40.1 ± 14.0 s for CFS). Calculated Vmax values were not difference between CFS and control subjects (P = 0.20)(Figure 6).

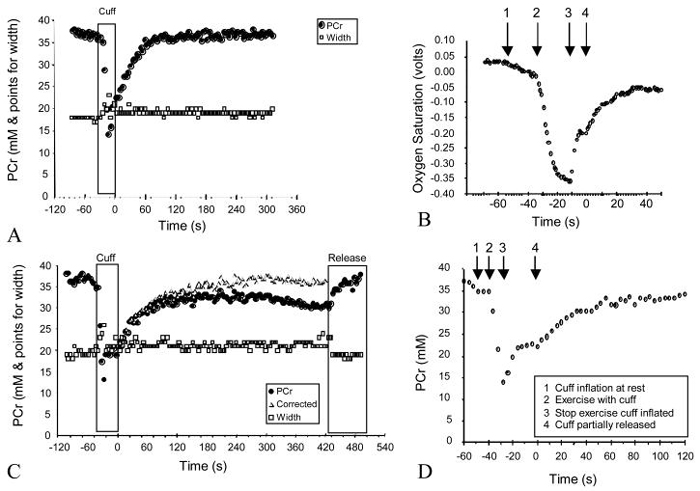

Figure 5.

Representative PCr and oxygen saturation kinetics following the partial cuff experiments. A. PCr height and width, with the PCr height normalized related to ATP peaks for with no partial cuff inflation during recovery. Note that width did not change during recovery. B. shows simultaneously collected oxygen saturation values. 1 = initial cuff inflation to occlude blood flow, note steady decline in oxygen saturation, 2 = start of exercise with cuff inflation, note rapid oxygen desaturation, 3 = end of exercise with cuff inflation, note that oxygen saturation values level off, 4 = full cuff release and start of recovery. C. PCr height and width during exercise with partial cuff inflation to 90 mmHg during recovery. Note that PCr levels did not fully recovery. The corrected PCr values reflect the assumption that blood volume increased linearly during cuff occlusion to the value see after complete cuff release. D shows PCr values during shown in panel A. 1 = initial cuff inflation to occlude blood flow, 2 = start of exercise with cuff inflation, note rapid PCr decrease, 3 = end of exercise with cuff inflation, note PCr values level off, 4 = full cuff release and start of recovery.

Figure 6.

A. End exercise ADP levels for the seven exercise bouts in CFS and control subjects. There were no significant differences between groups or between cuff pressures. B. Muscle Vmax values calculated from PCr recovery during partial cuff inflation. There were no significant differences between CFS and control subjects. Values are means and SD.

Partial cuff ischemia resulted in a progressive impairment of PCr recovery. This was demonstrated in Figure 5c. Interestingly, in most subjects partial cuff inflation resulted in not only a slower PCr recovery, but as shown in Figure 5c, a decrease in PCr levels that persisted until the final cuff release. This was interpreted as `dilution' of the PCr signal due to the accumulation of blood in the limb (from total occlusion of major veins with continued inflow of blood). This was corrected for by assuming a linear accumulation of blood in the sample area over the time period of partial cuff occlusion. PCr curve fitting was performed on these corrected values. Using the corrected values, calculated Vmax values progressively declined with increasing cuff occlusion pressure, with 90 mmHg pressures reducing Vmax to 30.7% and 35.3% of non-occluded Vmax for CFS and controls, respectively (Figure 5). Again, there was no different in calculated Vmax values between CFS and control subjects.

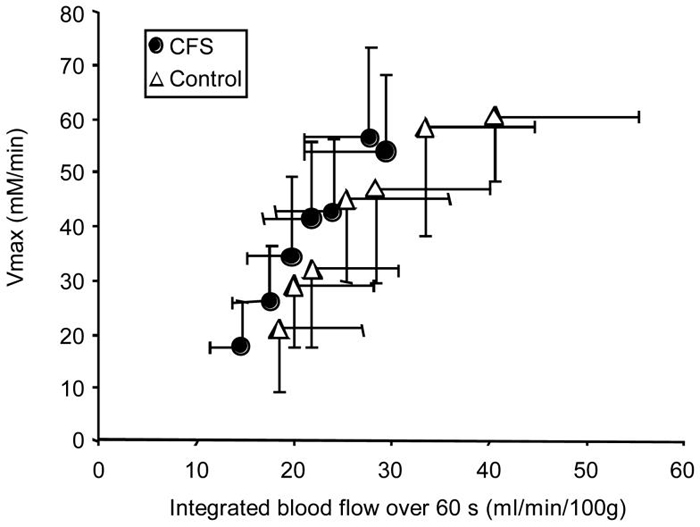

The main hypothesis of the study was that partial occlusion of blood flow would reduce Vmax to a greater degree in CFS compared to control subjects. This was not seen, as ANOVA of Vmax measurements across the different cuff pressures resulted in a P value of 0.20. However, the integrated blood flow during the first 60 seconds after exercise was significantly lower in the CFS group compared to controls (p < 0.001). The relationship between integrated blood flow and Vmax is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Summary of oxidative metabolism (Vmax) plotted relative to blood flow (integrated blood flow) in response to partial cuff occlusion for CFS and control subjects. While metabolism (Vmax) was not different between groups, integrated blood flow was. Values are means and SD.

DISCUSSION

This study found that hyperemic blood flow after exercise during partial cuff restriction was reduced in CFS patients compared to controls. Blood flow was measured as the integrated flow over the first 60 seconds of recovery, and took into account lean leg mass with no group differences in blood pressure. We also found that recovery of oxygen saturation was reduced in CFS patients after exercise, consistent with our previous studies(23). CFS patients have been reported to have altered sympathetic activity and impaired autonomic tone(7, 10, 30, 43). The measurements of integrated flow and oxygen delivery might reflect autonomic impairment. While there are no available studies on CFS to compare our blood flow measurements, previous studies have suggested that CFS patients have cholinergic abnormalities in peripheral microcirculation (19, 35). Patients with fibromyalgia, a related syndrome, have reported reduced blood flow (3) and reduced capillary densities (20) relative to control subjects.

The peak blood flow response for the no cuff exercise conditions was not reduced in the CFS patients compared to controls, in contrast to the integrated flow responses. The lack of a difference in peak blood flow responses following exercise was similar to our most recent study which found no differences in peak blood flow after cuff ischemia (25). It is not clear why we would obtain different conclusions for peak and integrated blood flow. One possibility is that integrated flow values might be more sensitive markers of flow abnormalities in CFS patients than peak flow. We have found altered rates of recovery of blood flow after ischemia in both older and spinal cord injured subjects(27, 29), consistent with altered autonomic tone in these groups(9, 36). These results suggest that the capacity for peak blood flow was not reduced in CFS patients compared to controls, but that the actual delivery of oxygen might be reduced due to alterations in the integrated flow response.

The question that comes from our results is what is the importance of the reduced integrated flow and oxygen delivery responses? Our primary hypothesis was that restricting blood flow during recovery would impair oxidative metabolism in CFS patients to a greater extent that control subjects. We found no evidence that this was true. Oxidative capacity measured with 31P MRS during recovery from exercise with partial cuff occlusion was not impaired in CFS subjects. We did see a graded decrease in blood flow and oxidative metabolism with increasing cuff pressure, suggesting that partial cuff inflation did restrict blood flow and did reduce oxidative metabolism. As shown in Figure 1, we took care to design the experiment to minimize residual levels of muscle oxygen prior to the partial cuff occlusion. This included applying the cuff prior to exercise to assist in reducing stored oxygen levels in the muscles, and keeping the cuff on the muscle for approximately 10 seconds after cessation of exercise to assure that PCr recovery was stopped. So while flow restriction did reduce oxidative metabolism, there was no evidence that CFS patients were more sensitive to flow restriction than control subjects.

A number of previous studies have examined the effects of flow restriction on muscle metabolism and function. Conrad and Green (6) found that cuff pressures of 50-60 mmHg reduced direct measures of resting arterial flow by 5-9% in a cat hindlimb preparation. In a study on humans, Hiatt et al. (15) found much larger changes with cuff pressures of 50 mmHg, including 44% decreases in femoral artery diameter directly under the cuff and a 38% decrease in blood velocity down stream of the cuff. These measurements were made under stable conditions and it is not clear how they compare to our measurements, as we were primarily concerned with changes in blood flow during the first minute after partial cuff occlusion. Sundberg et al.(37) found that lower body negative pressures of 50 mmHg reduced arterial blood flow by 16% during exercise, and also resulted in lower venous oxygen saturation and higher venous lactate levels during exercise. Cole and Brown used cuff occlusion during electrical stimulation, and found that cuff pressures of 50 and 80 mmHg resulted in force reductions of 15-22 % (4). Iwanaga, et al. (17) found cuff occlusion at systolic and diastolic blood pressures to have pressure dependent effects on work rate, phosphocreatine levels, and intracellular pH during exercise. Taken together, these studies support our findings that even relatively low occlusion pressures can restrict blood flow and impair muscle metabolism.

One of the complications of our approach is that partial arterial occlusion is also associated with venous occlusion. This dramatically altered the arterial velocity waveform (Figure 1), most likely due to back pressure associated with the accumulation of blood in the venous system. The accumulation of blood also influenced the PCr measurements as we could detect changes in PCr concentration in association with the change in cuff pressure (Figure 5). Partial cuff ischemia reduced PCr values and altered the shape of the PCr recovery curves. We chose to correct our PCr values using a linear increase in blood volume during the time period that the partial cuff pressure was applied. We based this in part on the NIRS results which showed that partial cuff ischemia increased blood volume. Interestingly, the increase in blood volume appeared to be primarily deoxygenated blood as the level of oxygen saturation was progressively reduced during partial cuff ischemia. These results suggest that alterations in blood volume need to be taken into account when evaluating the vascular response to partial cuff ischemia.

Another limitation of our study was the measurement of peak blood flow using two cardiac cycles. While the short measurement time interval allowed us to track the rapidly changing blood flows needed to measure a peak flow value, it does introduce some added variability. For example, we did not control for the effects of respiration on time averaged blood flow. We did use integrated flow over 60 seconds when comparing blood flow during partial cuff ischemia to PCr recovery rates. We felt that blood flow over 60 seconds would more accurately reflect oxygen delivery while PCr was being resynthesized. This would also reduce variability of the measurements due to respiration and other transient effects.

Other approaches have been used to evaluate muscle metabolism in response to altered oxygen delivery. Studies by Hogan et al.(16) showed that PCr levels during exercise were sensitive to the concentration of oxygen during exercise. The rate of PCr resynthesis was also altered by altering oxygen concentrations in inspired air, but only in well-trained subjects(32). It is hard to compare the magnitude of reduction in oxygen delivery in the studies that altered the concentrations of inspired oxygen to our study where we reduced blood flow. However, their results are consistent with ours and support the idea that oxidative metabolism is linked to oxygen delivery during exercise.

Oxidative metabolism, as measured by the rate of PCr recovery after exercise was not different between the CFS patients and our controls in this study. This was reported in an earlier manuscript (25). In addition, CFS patients showed the same degree of reduction of oxidative metabolism as control subjects with partial cuff occlusion to reduced blood flow. The lack of impairment of oxidative metabolism in CFS patients was consistent some previous studies(18), but not others(23, 24). It is not clear why the different studies have different conclusions, especially our current study and our previous study, which evaluated CFS and controls subjects from the same source and using basically the same equipment and protocols. Most of the subjects in our study reported `severe' CFS symptoms, so we feel that altered muscle metabolism is not a requirement for CFS symptoms to be present. It is possible that our lack of change in blood flow responses was due to the lack of metabolic differences, and that CFS patients with clearly abnormal oxidative metabolism would have abnormal blood flow.

In summary, CFS patients had rates of oxidative metabolism that were not different from control subjects, even with partial restriction of blood flow. This suggests that the CFS symptoms that these patients reported were not caused by peripheral abnormalities in oxidative metabolism. However, we did find evidence that CFS patients had reduced oxygen delivery, based both on NIRS measurements of the rate of recovery after exercise, and reductions in the integrated flow response to partial arterial occlusion. These measurements do support the hypothesis that CFS patients have abnormal control of circulation, perhaps due to altered sympathetic and or parasympathetic tone. However, it is not clear how significant the changes in control of circulation are as they were not associated with changes in muscle oxidative metabolism, which is normally highly sensitive to oxygen delivery. Partial cuff occlusion resulted in graded reductions in oxidative metabolism, even with occlusion pressure below diastolic pressure. This suggests that partial occlusion of blood flow could be a useful method of evaluating oxygen delivery and muscle metabolism as long as the effects of venous filling are taken into account.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Supported in part by NIH HL-65179, NIH AI-32247 and NIH RR02305. We would like to thank Krzysztof Wroblewski for his help in developing the PCr analysis program. We would like to thank Allison DeVan for her help in data analysis and data cleaning.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arnold D, Bore P, Radda G, Styles P, Taylor D. Excessive intracellular acidosis of skeletal muscle on exercise in a patient with a post-viral exhaustion/fatigue syndrome. Lancet. 1984;i:1367–1369. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91871-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnes P, Taylor D, Kemp G, Radda G. Skeletal muscle bioenergetics in the chronic fatigue syndrome. Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery Psychiatry. 1993;56:679–683. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.56.6.679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennett R, Clark S, Campbell S, Ingram S, Burchardt C, Nelson D, Porter J. Symptoms of Raynaud's syndrome in patients with fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheumatology. 1991;34:264–269. doi: 10.1002/art.1780340303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cole MA, Brown MD. Response of the human triceps surae muscle to electrical stimulation during varying levels of blood flow restriction. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2000;82:39–44. doi: 10.1007/s004210050649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conley K. Cellular energetics during exercise. Advances in Veterinary Science and Comparative Medicine. 1994;38A:1–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conrad MC, Green H. Evaluation of venous occlusion plethysmography. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1961;16:289–292. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1961.16.2.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cordero D, Sisto S, Tapp W, LaManca J, Pareja J, Natelson B. Decreased vagal power during treadmill walking in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Clinical Autonomic Res. 1996;6:329–333. doi: 10.1007/BF02556303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeBecker P, Roeykens J, Reynders M, McGregor N, DeMeirleir K. Exercise capacity in chronic fatigue syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3270–3277. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.21.3270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dinenno FA, Jones PP, Seals DR, Tanaka H. Limb Blood Flow and Vascular Conductance Are Reduced With Age in Healthy Humans: Relation to Elevations in Sympathetic Nerve Activity and Declines in Oxygen Demand. Circulation. 1999;100:164–170. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.2.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freeman R, Komaroff A. Does the chronic fatgue syndrome involve the autonomic nervous system? Am. J. Med. 1997;102:357–364. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)00087-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fukuda K, Straus S, Hickie I, Sharpe MC, Dobbins JG, Komaroff A. Chronic fatigue syndrome: a comprehensive approach to its definition and study. Ann. Intern. Med. 1994;121:953–958. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-121-12-199412150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fulcher K, White PD. Strength and physiological response to exercise in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiary. 2000;69:302–307. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.69.3.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fulle S, Mecocci P, Fano G, Vecchiet I, Vecchiet A, Racciotti D, Cherubini A, Pizzigallo E, Vecchiet L, Senin U, Beal M. Specific oxidative alterations in vastus lateralis muscle of patients with the diagnosis of chronic fatigue syndrome. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2000;29:1252–1259. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00419-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gibson H, Carroll N, Clague J, Edwards R. Exercise performance and fatigability in patients with chronic fatgue syndrome. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiary. 1993;56:993–998. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.56.9.993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hiatt W, Huang SK, Regensteiner J, Micco AJ, Ishimoto G, Manco-Johnson M, Drose J, Reeves J. Venous occlusion plethysmography reduces arterial diameter and flow velocity. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1989;66:2239–2244. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1989.66.5.2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hogan MC, Richardson RS, Haseler LJ. Human muscle performance and PCr hydrolysis with varied inspired oxygen fractions: a 31P-MRS study. J Appl Physiol. 1999;86:1367–1373. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.86.4.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iwanaga K, Sakurai M, Minami T, Kikuchi Y. Effect of restricted blood flow on intracellular pH threshold of working muscle. Ann. Physiol. Anthrop. 1993;12:181–188. doi: 10.2114/ahs1983.12.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kent-Braun J, Sharma K, Weiner M. Central basis of muscle fatigue in chronic fatigue syndrome. Neurology. 1993;43:125–131. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.1_part_1.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khan F, Spence V, Kennedy G, Belch JJ. Prolonged acetylcholine-induced vasodilatation in the peripheral microcirculation of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2003;23:282–285. doi: 10.1046/j.1475-097x.2003.00511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindh M, Johansson G, Hedberg M, Henning G, Grimby G. Muscle fiber characteristics, capillaries and enzymes in patients with fibromyalgia and controls. Scand. J. Rheum. 1995;24:34–37. doi: 10.3109/03009749509095152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCully K, Fielding R, Evans W, Leigh J, Jr, Posner J. Relationships between in vivo and in vitro measurements in metabolism in young and old human calf muscles. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1993;75:813–819. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.75.2.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCully K, Natelson B. Impaired oxygen delivery in chronic fatigue syndrome. Clinical Science. 1999;97:603–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCully K, Natelson B. Impaired oxygen delivery to muscle in chronic fatigue syndrome. Clinical Science. 1999;97:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCully K, Natelson B, Iotti S, Sisto S, Leigh J. Reduced oxidative muscle metabolism in chronic fatigue syndrome. Muscle and Nerve. 1996;19:621–625. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4598(199605)19:5<621::AID-MUS10>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCully KK, Smith S, Rajaei S, Leigh JS, Jr, Natelson BH. Blood flow and muscle metabolism in chronic fatigue syndrome. Clin Sci (Lond) 2003;104:641–647. doi: 10.1042/CS20020279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Montague T, Marrie T, Bewick D, Spencer C, Kornreich F, Horacek B. Cardiac effect of common viral illnesses. Chest. 1988;94:919–925. doi: 10.1378/chest.94.5.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olive J, DeVan A, McCully K. The effects of aging and activity on muscle blood flow. Dynamic Medicine. 2002;1 doi: 10.1186/1476-5918-1-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olive JL, McCully KK, Dudley GA. Blood flow response in individuals with incomplete spinal cord injuries. Spinal Cord. 2002;40:640–646. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olive JL, Slade JM, Dudley GA, McCully KK. Blood flow and muscle fatigue in SCI individuals during electrical stimulation. J Appl Physiol. 2003;94:701–708. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00736.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pagani M, Lucini D, Mela G, Langewitz W, Malliani A. Sympathetic overactivity in subjects complaining of unexplained fatigue. Clinical Science. 1994;87:655–661. doi: 10.1042/cs0870655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paganini AT, Foley JM, Meyer RA. Linear dependence of muscle phosphocreatine kinetics on oxidative capacity. Americal Journal Physiology. 1997;272:C501–510. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.272.2.C501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Richardson RS, Grassi B, Gavin TP, Haseler LJ, Tagore K, Roca J, Wagner PD. Evidence of O2 supply-dependent VO2 max in the exercise-trained human quadriceps. J Appl Physiol. 1999;86:1048–1053. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.86.3.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sargent C, Scroop G, Nemeth P, Burnet R, Buckey J. Maximal oxygen uptake and lactate metabolism are normal in chronic fatigue syndrome. Med Sci Sports Exer. 2002;34:51–56. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200201000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schluederberg A, Straus S, Peterson P, Blumenthal S, Komaroff A, Spring S, Landay A, Buchwald D. Chronic fatigue syndrome research: definition and medical outcome assessment. Ann. Intern. Med. 1992;117:325–331. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-117-4-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spence VA, Khan F, Belch JJ. Enhanced sensitivity of the peripheral cholinergic vascular response in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Am J Med. 2000;108:736–739. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00407-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stjernberg L, Blumberg H, Wallin BG. Sympathetic activity in man after spinal cord injury. Outflow to muscle below the lesion. Brain. 1986;109(Pt 4):695–715. doi: 10.1093/brain/109.4.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sundberg CJ, Kaijser L. Effects of graded restriction of perfusion on circulation and metabolism in the working leg; qunatification of a human ischemia-model. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 1992;146:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1992.tb09386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takahashi H, Inaki M, Fujimoto K, Katsuta S, Anno I, Niitsu M, Itai Y. Control of the rate of phosphocreatine resynthesis after exercise in trained and untrained human quadriceps muscles. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1995;71:396–404. doi: 10.1007/BF00635872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van der Werf S, Prins J, Vercoulen JH, van der Meer JW, Bleijenberg G. Identifying physicial activity patterns in chronic fatigue syndrome using actigraphic assessment. J. Psychosomatic Res. 2000;49:373–379. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(00)00197-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wagemaker H. Chronic fatigue syndrome: the physiology of people on the low end of the spectrum of physical activity? Clinical Sci. 1999;97:6111–6613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wagemakers A, Coakley J, Edwards RHT. The metabolic consequences of reduced habitual activities in patients with muscle pain and disease. Ergonomics. 1988;31:1519–1527. doi: 10.1080/00140138808966801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Walter G, Vandenborne K, McCully K, Leigh J. Noninvasive measurement of phosphocreatine recovery kinetics in single human muscles. American Journal of Physiology. 1997;272:C525–C534. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.272.2.C525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilke W, Fouad-Tarazi F, Cash J, Calabrese L. The connection between chronic fatigue syndrome and neurally mediated hypotension. Cleveland Clinic J. Med. 1998;65:261–266. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.65.5.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]