Abstract

Objective

This research examined whether additional forms of family violence (partner-child aggression, mother-child aggression, women’s intimate partner violence [IPV]) contribute to children’s adjustment problems in families characterized by men’s severe violence toward women.

Methods

Participants were 258 children and their mothers recruited from domestic violence shelters. Mothers and children completed measures of men’s IPV, women’s IPV, partner-child aggression, and mother-child aggression. Mothers provided reports of children’s internalizing and externalizing behavior problems; children provided reports of their appraisals of threat in relation to interparent conflict.

Results

After controlling for sociodemographics and men’s IPV: 1) each of the additional forms of family violence (partner-child aggression, mother-child aggression, women’s IPV) was associated with children’s externalizing problems; 2) partner-child aggression was associated with internalizing problems; and 3) partner-child aggression was associated with children’s threat appraisals. The relation of mother-child aggression to externalizing problems was stronger for boys than for girls; gender differences were not observed for internalizing problems or threat appraisals.

Conclusions

Men’s severe IPV seldom occurs in the absence of other forms of family violence, and these other forms appear to contribute to children’s adjustment problems. Parent-child aggression, and partner-child aggression in particular, are especially important. Systematic efforts to identify shelter children who are victims of parental violence seem warranted.

Practice implications

Men’s severe intimate partner violence seldom occurs in the absence of other forms of family violence (partner-child aggression, mother-child aggression, and women’s intimate partner violence), and these different forms of family violence all contribute to children’s adjustment problems. Treatment programs for children who come to domestic violence shelters should address these different forms of family violence, especially parent-child aggression.

Introduction

Children in families characterized by men’s severe intimate partner violence (IPV) are more likely to experience externalizing and internalizing problems than children in families with either no IPV (e.g., Wolfe, Jaffe, Wilson, & Zak, 1985) or less severe IPV (e.g., Fantuzzo et al., 1991; Rossman & Rosenberg, 1992). Most studies demonstrating such relations have focused on samples recruited from domestic violence shelters (Jouriles, McDonald, & Skopp, 2005). In these samples, the families and the researchers typically identify men’s IPV as the critical form of family violence (e.g., men’s violence was what prompted the women to seek shelter). Descriptions of the men’s IPV in such samples often indicate multiple beatings and the threat or use of knives and guns (Jouriles, McDonald, Norwood, Ware, Spiller, & Swank, 1998). Such extreme violence naturally commands attention and is often assumed to be a major reason for the high prevalence of adjustment problems among children in families recruited from domestic violence shelters (Jouriles, Norwood, McDonald, & Peters, 2001).

Unfortunately, the family context in which these children live often includes exposure to other forms of family violence as well. For example, parental physical aggression toward children is a robust correlate of men’s IPV, with rates of severe parental physical aggression toward children often exceeding 40% in domestic violence shelter samples (Appel & Holden, 1998; Jouriles, McDonald, Slep, Heyman, & Garrido, 2008). Similarly, in families in which the men engage in severe IPV, up to 50% of the women also engage in IPV (Sorenson, Upchurch & Shen, 1996; Slep & O’Leary, 2005). The extent to which these other forms of family violence (parental physical aggression toward children and women’s IPV) adversely affect children who have been exposed to men’s severe IPV is important to consider from a scientific as well as a practical perspective (see Wolfe, Crooks, Lee, McIntyre-Smith, & Jaffe, 2003 for review).

Social learning theory (Bandura, 1977) posits that children develop beliefs and behavior patterns from observing and interacting with others, particularly salient others such as their parents. Having two parents who engage in IPV, rather than one, can be conceptualized as providing children with more opportunities to observe aggression. Similarly, families in which the parents engage in both IPV and aggression toward children, rather than only IPV, might be regarded as families in which the children have additional opportunities for learning aggressive behavior patterns. Social learning theorists have also suggested that children are more likely to incorporate the values and behaviors of the parent with whom they more closely identify, most typically the same-sex parent (Bandura, 1977; Crick & Dodge, 1994), suggesting that women’s IPV and mother-child aggression might disproportionately affect girls. Consistent with this view, in a pediatric clinic sample, mothers’ IPV predicted girls’ externalizing problems, whereas fathers’ IPV predicted boys’ externalizing problems (Crockenberg & Langrock, 2001).

The cognitive contextual model points to the importance of the children’s interpretations of marital conflict as determinants of their adjustment (Grych & Fincham, 1990; Grych, Fincham, Jouriles, & McDonald, 2000). The model holds that children appraise interparent conflict according to its threat to family stability and to their own well-being, and children who appraise their parents’ marital conflict as threatening are more likely to experience internalizing problems. Families characterized by multiple forms of family violence (e.g., men’s severe IPV and parental aggression toward children) tend to be unpredictable and extremely chaotic (Patterson, 1982). Thus, children might be expected to feel more threatened and experience more internalizing problems when both IPV and parent-child aggression occur within the family as opposed to only IPV, or when both, rather than one, of the caregivers engages in IPV.

There is empirical evidence, albeit sparse and sometimes equivocal, that parent-child aggression is related to children’s adjustment problems in families characterized by men’s severe IPV (e.g., Hughes, Parkinson, & Vargo, 1989; Jouriles, Barling, & O’Leary, 1987; Jouriles & Norwood, 1995; Sternberg, Lamb, Guterman, & Abbott, 2006; Wolfe et al., 2003). However, these studies rarely differentiate between mother-child and father-child (or partner-child) aggression, which as discussed above is a potentially important distinction from a social learning theory perspective. In addition, these studies rarely include data on parent-child aggression collected from multiple sources, which is an important methodological limitation (Appel & Holden, 1998; Jouriles, Mehta, McDonald, & Francis, 1997). Moreover, no studies to date have considered the contributions of women’s IPV in examining children’s adjustment problems within families characterized by severe men’s IPV.

Historically, it has been contended by many that women’s IPV primarily reflects self-defense (Swan & Snow, 2002), particularly when it occurs in the context of severe men’s IPV. It has also been suggested that questioning or acknowledging otherwise does women an injustice, risking the possible loss of legitimate support for women who are victims of serious violence (e.g., White, Smith, Koss, & Figueredo, 2000). On the other hand, it has also been argued that there are sufficient data to suggest that women do engage in violence against their partners, and whether or not the violence is in self-defense, lack of knowledge about the nature and dynamics of IPV in general – not just men’s IPV – limits our ability to understand its effects (e.g., Capaldi & Owen 2001; Ehrensaft, Moffitt, & Caspi, 2004; Wolfe et al., 2003). Setting aside questions of resource allocation and social justice, examining whether children are adversely affected by the violence of women in families characterized by men’s severe IPV holds implications for policy, theory, and practice, and for those reasons it warrants consideration.

The present research is designed to examine the associations of children’s adjustment problems with men’s and women’s parent-child aggression and women’s IPV within families characterized by men’s severe IPV. On the basis of theory and research reviewed above, it is hypothesized that men’s and women’s parent-child aggression and women’s IPV will each contribute independently of the others in the prediction of children’s adjustment problems and threat appraisals. Mother-child aggression and women’s IPV are also expected to be more strongly associated with the adjustment problems and threat appraisals of girls rather than boys.

Method

This is a secondary analysis of data collected in a series of projects on IPV and children’s adjustment problems (e.g., Grych et al., 2000; Jouriles, Spiller, Stephens, McDonald, & Swank, 2000). The measures used in this report are a subset of those collected in the series of projects. All research procedures had Institutional Review Board approval. Informed consent was obtained from mothers; children verbally assented to participate.

Participants

Participants were 258 children 8–12 years old and their mothers (143 girls, 115 boys). Participants were recruited from shelters that provide temporary residence to women and children seeking refuge from domestic violence. Families eligible for participation were those in which (1) the mother and child both spoke English, (2) the mother indicated that she had sought shelter from violence perpetrated by an intimate male partner, and (3) the mother or the child reported on the Conflict Tactics Scales (see Measures section) that at least one incident of physical IPV had been directed toward the mother in the previous year by her male partner. In families with more than one eligible child in the age range for the study, the oldest eligible child was selected for participation.

Mothers were 33.10 years old (SD = 5.40) and children were 10.0 years old (SD = 1.45) on average. Thirty-nine percent of mothers reported their ethnicity as Caucasian, 31% African American, 30% Hispanic, and 1.2% indicated multi-ethnic or other. Mothers, on average, possessed a high-school education (mean years = 11.59, SD = 3.01) and reported a mean annual family income of $13,692 (SD = $13,557).

Procedure

After establishing eligibility and obtaining informed consent, mothers and their children were interviewed at the shelter where they were residing. Mother and child interviews were conducted in separate, private rooms by different interviewers. Interviewers took time to establish rapport with participants before obtaining informed consent from mothers and verbal assent from children. All measures were read aloud to mothers and to children to ensure comprehension. The research staff worked in conjunction with the shelters to provide referrals to mothers who provided information during the interview that suggested services (e.g., medical, legal) might be needed or when mothers requested them. Necessary referrals were also made to Child Protective Services when child abuse was reported, as was discussed in the informed consent.

Measures

Intimate Partner Violence

Mother and child reports of mother-partner and partner-mother IPV were assessed using the 8-item physical aggression subscale of the Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS; Straus, 1979). The CTS is widely used in research on IPV and includes minor (e.g., pushed, grabbed or shoved; slapped) and severe (e.g., kicked, bit or hit with a fist; beat up) violence subscales. Mothers and children reported on acts of violence that occurred during the 12 months preceding the assessments, indicating the frequency of occurrence of each act on a 7-point scale (0 = none to 6 = more than 20 times). Responses were summed to create a total violence score, a scoring method commonly used in research on violent populations (Straus & Gelles, 1990).

Parent-child aggression

Mother and child reports of parent-child physical aggression were measured with eight items from the Physical Violence Subscale of the Parent-Child Conflict Tactic Scale (PCTS; Straus, 1979). The PCTS is also widely used in research on family violence and includes the same acts of minor (e.g., pushed, grabbed or shoved; slapped) and severe (e.g., kicked, bit, or hit with a fist; beat up) violence as the CTS. Item scores were summed to arrive at a total violence score. In the original data from which data for this study was drawn, a 6-point scale rather than a 7-point scale was used to score mothers’ CTS responses for a subsample of the participants (n = 75). To equate scores from the 6-point and 7-point scales, mothers’ CTS scores were converted to z-scores by standardizing them (M = 0, SD = 1) within the two subsamples.

Child behavior problems

Mothers completed the Internalizing and Externalizing Disorder Scales of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991). The CBCL is a widely used measure of children’s adjustment problems. On a 3-point scale (0 = not true, 1 = somewhat/sometimes true, 2 = very true/often true), mothers rated the extent to which items reflecting internalizing problems (e.g., unhappy, sad, depressed, worries) and externalizing problems (e.g., cruel, bullying, or mean to others) described their children’s behavior during the previous 6 months. The CBCL is a widely used measure of children’s adjustment problems, with well-documented psychometric properties (Achenbach, 1991). T-scores are reported for descriptive purposes, but raw scores were used in data analyses as the analyses evaluate interaction terms that include Child Sex.

Threat appraisals

The threat subscale of the Children’s Perceptions of Interparent Conflict Scale (CPIC; Grych, Seid, & Fincham, 1992) was used to assess children’s appraisals of threat in relation to interparent conflict. The threat scale includes 12 items that children rate on a 3-point scale (2 = true, 1 = sort of true, 0 = false). Sample items include: When my parents argue I’m afraid something bad will happen; When my parents argue I’m afraid they will yell at me too.

Results

Sample characteristics

Acts of IPV were judged to have occurred if the mother, the child, or both, indicated that they had occurred on the CTS. Severe IPV was judged to have occurred if the mother, the child, or both indicated on the CTS that at least one of the severe violence items had occurred. Acts of parent-child aggression and severe parent-child aggression on the CTS were similarly considered. Almost all of the mothers (96.4%) were reported to have been the victim of one or more acts of men’s severe IPV within the previous year; 67.1% of the mothers were reported to have committed one or more acts of severe IPV in the previous year. PCTS responses indicated that 45% of partners and 35.3% of mothers were reported by the mother, child or both to have committed one or more acts of severe aggression toward the child in the previous year. A CBCL T-score ≥ 60 (i.e., ≥ 1 SD above the mean of the normative sample) was considered to reflect clinical levels of problems. This is a somewhat liberal cutoff (T-scores between 60 and 63 may be considered borderline clinical; Achenbach, 1991), but captures those children displaying significant problems and those with lower levels of problems who are heightened risk for further problems. Using this criterion, 40% of children were reported to have clinical levels of externalizing problems (12% T-score 60–63, 28% T-score > 63) and 49% were reported to have clinical levels of internalizing problems (10% T-score 60–63, 39% T-score > 63). Internalizing and externalizing scores were both ≥ 60 for 31% of the sample, and were both < 60 for 40%.

Data reduction and preliminary analyses

As is common in studies of family violence, the violence scores on 7 of the 8 measures (all except for mothers’ reports of partner-mother violence) were positively skewed. Scores on the scales with skewed distributions were therefore log-transformed for analyses. The mean of mother and child reports on each of the forms of violence (partner-mother IPV, mother-partner IPV, mother-child aggression, and partner-child aggression) was used in analyses. Since the scores were not equivalent across reporters for 3 of the 4 forms of violence (e.g., some were raw scores, some had been log-transformed) the raw and log-transformed scores were standardized prior to averaging them to equate them. Correlations among the study variables and their means and standard deviations are presented in Table 1. Women’s IPV, partner-child aggression, and mother-child aggression were associated with children’s externalizing problems. Partner-child aggression and mother-child aggression were associated with children’s internalizing problems. Men’s IPV and partner-child aggression were associated with children’s threat appraisals. Among the sociodemographic variables (not presented in the table), mother’s income, child age, mother age, and mother education level were associated with one or more of the three primary outcome variables (externalizing problems, internalizing problems, and threat appraisals). Thus, the need to control for these variables was evaluated in subsequent analyses testing the study hypotheses.

Table 1.

Correlations and Means (SD) of study variables, n = 258

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Partner-mother IPV | .01 (.82) | ||||||

| 2. Mother-partner IPV | .34** | .01 (.82) | |||||

| 3. Partner-child aggression | .30** | .01 | .00 (.86) | ||||

| 4. Mother-child aggression | .02 | .15* | .28** | .00 (.76) | |||

| 5. Externalizing problems | .01 | .16* | .24** | .36** | 13.75 (10.40) | ||

| 6. Internalizing problems | .02 | .01 | .17** | .13* | .47** | 13.17 (9.86) | |

| 7. Threat appraisals | .26** | .10 | .19** | .00 | −.01 | −.01 | 13.70 (4.87) |

Note: Correlations for mother-partner IPV, mother-child aggression, and partner-child aggression computed on log-transformed scores; means (SDs) and correlations for externalizing and internalizing problem scores and threat appraisals are calculated from raw scores.

p < .05,

p < .01.

Associations among the forms of family violence and child problems

Separate multiple regression models were computed for each of the three dependent variables (externalizing problems, internalizing problems, and threat appraisals). Each model included the three predictor variables of interest (women’s IPV, partner-child aggression, and mother-child aggression) as well as men’s IPV as a control variable. For each analysis, an initial model was computed that also included mother age, mother education, family income, child age, child sex, and the Women’s IPV × Child Sex, Partner-Child Aggression × Child Sex, and Mother-Child Aggression × Child Sex interaction terms. Significant demographic predictors and interaction terms from the initial models were retained in the final analyses; nonsignificant terms were dropped. The results of the final regression analyses are summarized in Table 2. Each of the overall models was associated with its respective outcome of interest, externalizing problems, F(7, 250) = 9.04, p < .001, internalizing problems, F(5, 249) = 3.18, p < .01, and threat appraisals, F(7, 247) = 5.81, p < .0001.

Table 2.

Relation of forms of violence to children’s adjustment problems and threat appraisals

| Variable | B | SEB | F | sr2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Externalizing Problems (n = 258) | df(1, 250) | |||

| Partner-mother IPV | −1.12 | .82 | 1.84 | .01 |

| Mother-partner IPV | 1.82 | .79 | 5.33* | .02 |

| Partner-child aggression | 2.32 | .77 | 9.12** | .03 |

| Mother-child aggression | 5.01 | 1.04 | 22.77** | .07 |

| Child sex | −.51 | 1.24 | .17 | .00 |

| Child age | −.95 | .41 | 5.30* | .02 |

| Child Sex × Mother-Child Aggression | −3.47 | 1.63 | 4.55* | .01 |

| 2. Internalizing Problems (n = 255) | df (1, 249) | |||

| Partner-mother IPV | −.24 | .84 | .08 | .00 |

| Mother-partner IPV | .11 | .84 | .02 | .00 |

| Partner-child aggression | 1.98 | .79 | 6.20* | .02 |

| Mother-child aggression | 1.04 | .85 | 1.49 | .01 |

| Income | .00 | .00 | 6.40* | .02 |

| 3. Threat appraisals (n = 255) | df (1, 247) | |||

| Partner-mother IPV | 1.13 | .40 | 7.86** | .03 |

| Mother-partner IPV | .12 | .39 | .10 | .00 |

| Partner-child aggression | .75 | .37 | 4.06* | .01 |

| Mother-child aggression | −.29 | .41 | .50 | .00 |

| Mother education | −.33 | .10 | 10.89** | .04 |

| Child Age | −.44 | .20 | 4.58* | .02 |

| Mother Age | .12 | .06 | 4.48* | .02 |

Note:

p < .05

p < .01; for Child Sex, male = 0, female = 1.

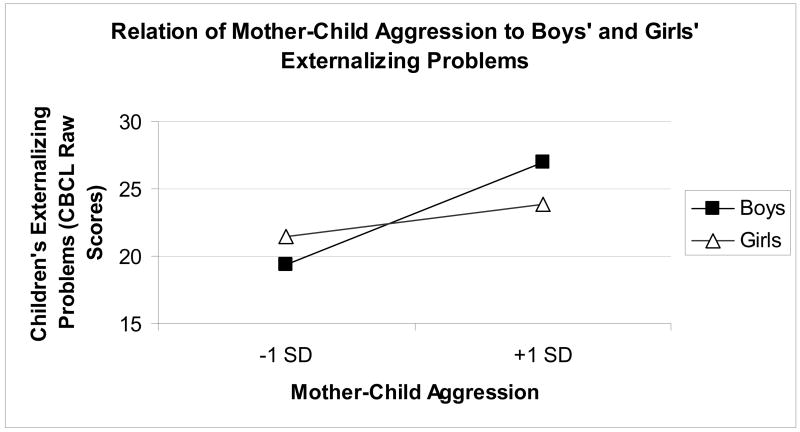

In the model for externalizing problems, women’s IPV, F(1, 256) = 5.33, p < .05, semi-partial r2 (sr2) = .02, partner-child aggression, F(1, 256) = 9.12, p < .001, sr2 = .03, and mother-child aggression, F(1, 256) = 22.77, p < .0001, sr2 = .07, were positively associated with externalizing problems after controlling for the other forms of violence and demographic variables. In addition, child age, F (1, 256) = 5.30, p < .05, sr2 = .02, and the Child Sex × Mother-Child Aggression interaction term, F(1, 256) = 4.55, p < .01, sr2 = .01, were negatively associated with externalizing problems. To understand the form of the interaction, the relation of mother-child aggression to externalizing problems was plotted separately for girls and boys, following the guidelines of Aiken and West (1991). As indicated in Figure 1, the relation is stronger for boys, simple slope = 5.01, t(150) = 4.06, p = .0001, than for girls, simple slope = 1.54, t(150) = 1.36, p = ns.

Figure 1.

Relation of mother-child aggression to externalizing problems for boys and for girls.

In the model for internalizing problems, partner-child aggression, F(1, 253) = 6.20, p < .01, sr2 = .02, was positively associated with internalizing problems after controlling for other forms of violence and family income. Family income was also positively associated with internalizing problems, F(1, 253) = 6.40, p < .05, sr2 = .02.

Finally, for children’s threat appraisals, partner-child aggression, F(1, 253) = 4.06, p < .05, sr2 = .01, was positively associated with threat appraisals after controlling for other forms of violence and the demographic variables. Among the demographic variables, mother age was positively associated with threat appraisals, F(1, 254) = 4.48, p < .05, sr2 = .02; mother education, F(1, 253) = 10.89, p < .01, sr2 = .04, and child age, F(1, 254) = 4.58, p < .05, sr2 = .02 were negatively associated with threat appraisals. Men’s IPV, F(1, 254) = 7.86, p < .01, sr2 = .03, was also positively associated with threat appraisals.

Discussion

A great deal of research with shelter families has concluded that men’s IPV is associated with children’s externalizing and internalizing problems. The present research is among the first studies to examine whether other forms of family violence (partner-child aggression, mother-child aggression, women’s IPV) are important for understanding the adjustment problems of children exposed to men’s severe IPV. Strengths of this study include controlling for key sociodemographic variables, collecting data from multiple informants on family violence and children’s adjustment, and recruitment of a large sample of shelter families. It appears that when other forms of aggression toward family members are disaggregated and considered, two key points emerge. First, as others have found (e.g., see Margolin & Gordis, 2000 and Appel & Holden, 1998 for reviews), men’s severe IPV seldom occurs in the absence of other forms of family violence; women’s IPV, partner-child aggression and mother-child aggression are also common. Second, these other forms of family violence also appear to contribute to children’s adjustment problems. The observed effect sizes for the relations between children’s adjustment problems and the various forms of family violence in this sample were generally small (sr2 range = .01–.07). However, they reflect effects of each of the specific forms of violence, after controlling for all of the other forms. Such findings suggest that the influence of family violence on children’s adjustment derives from aspects of violence that are common across the multiple forms of violence, as well as aspects that are specific to each of them.

Not surprisingly, parent-child aggression, particularly partners’ aggression toward children, appears especially important. After controlling for the other forms of family violence, partner-child aggression was uniquely associated with each of the child variables in this research. Parent-child aggression is a robust predictor of children’s adjustment problems, and children who accompany their mothers to domestic violence shelters are at high risk for experiencing such aggression. Similar to the findings of others (Straus & Gelles, 1990; Meichenbaum, 1994), in the 6 months prior to their participation in this study, almost half of the children (45%) in this sample had been the target of severe aggression by their mother’s partner; just over one third (35%) had been the target of severe aggression by their mother. In addition, at least half of the children were reported to exhibit elevated levels of adjustment problems. These results have implications for policy and direct services for children of women who come to domestic violence shelters. Given the over 1 million children who reside in domestic violence shelters each year (Jouriles, 2000), and their elevated risk for violent victimization or psychological adjustment problems, a public health perspective would suggest that domestic violence shelters be considered a point of entry into a system of care for these children. Systematic efforts to identify and treat children in domestic violence shelters who are victims of parental abuse or who have significant mental health problems seem warranted.

There are, however, barriers to the potential success of such efforts. For example, there appear to be few attempts to assess carefully the extent to which children have been the targets of parental aggression by agencies primarily serving victims of IPV. There are, of course, practical considerations, such as limited resources that women’s shelters have for conducting such assessments. Also, although domestic violence agencies offer many services for children, they must also approach with care any decision to implement policies that could have deleterious consequences for their adult clients. For example, results of direct assessment of parental aggression toward the children would likely increase the number of reports of abuse to child welfare agencies, and perhaps occasions for removal of children from the mother’s custody, custody disputes between women and their violent partners, and charges of victimized mothers failing to protect their children from their partner’s violence. The potential for such outcomes would likely deter at least some victimized women from seeking services to escape the violence. Finally, it is difficult at best to offer effective services targeting children’s mental health during a typical 30- to 60-day shelter stay, and almost no women return to domestic violence agencies to seek mental health services for their children after the family has departed from the shelter (see Jouriles, McDonald et al., 2001; McDonald, Jouriles, & Skopp, 2006). These issues are not trivial, nor are their solutions simple. Whether or not parental aggression toward children is assessed by the agencies serving these families, there is emerging evidence that intensive interventions that target parenting skills in families who have departed shelters effectively reduce children’s adjustment problems (Jouriles et al., 2001; McDonald et al., 2006). Such interventions help reduce parent-child aggression, but are not designed to directly address the IPV. To our knowledge, there is no intervention that has been empirically demonstrated to address both aspects of family violence.

Women’s IPV in this research was uniquely associated with children’s externalizing problems, but not with internalizing problems or appraisals of threat. Modeling and social learning theory explanations could account for the relation with externalizing problems that emerged over and above the contributions of men’s IPV and mother-child and partner-child aggression. That is, exposure to more types of violence and less exposure to prosocial models of relationship functioning may increase the likelihood that children will learn and draw upon aggressive responses and strategies. However, it is important to note that the findings were not consistent with same-sex modeling hypotheses (Bandura, 1977; Crick & Dodge, 1994). Another possibility is that children’s externalizing behaviors may be more tolerated or less effectively managed, and thus maintained, in families in which aggression is more frequently utilized by parents. This might be especially true for male children, which is consistent with our finding of a stronger relation between mother-child aggression and boys’ rather than girls’ externalizing problems. Such findings point to possible targets of intervention for boys exposed to family violence.

The models analyzed in this research accounted for more variance in externalizing problems (20%) than internalizing problems (6%) or threat appraisals (14%). This pattern of results may be partly an artifact of the assessment of child adjustment. That is, trauma symptoms, which are typically conceived of as internalizing problems, were not specifically assessed in this research. There is substantial literature on trauma symptoms among physically abused children, and a developing literature on trauma symptoms among children exposed to IPV. If the assessment of children’s internalizing problems included a stronger assessment of trauma symptoms, it is quite possible that the model would have accounted for a greater proportion of the variance in internalizing problems. Presently, there is very little research attempting to disentangle the specific nature of the experiences of children in partner-violent families and the consequences of those experiences for different aspects of children’s adjustment (trauma symptoms, externalizing symptoms, no symptoms). The potential overlap of trauma symptoms with both externalizing and internalizing problems, and the increased likelihood of these various outcomes among children in violent families, calls for a better understanding of the mechanisms by which family violence exerts its effects. Explicating such mechanisms may help identify specific targets of intervention for specific types of problems subsequent to family violence and could thus help refine interventions for children in violent homes.

The data for this study are cross-sectional and preclude conclusions regarding causation. In addition, the CTS assesses frequency of acts of violence, so conclusions can not be drawn regarding the dynamics or context of men’s versus women’s IPV that may account for their differential association with children’s behavior problems. Whether partner’s use of IPV co-occurs with, precedes or follows women’s IPV, and the extent to which woman’s IPV reflects self-defense or retribution are not addressed by our research. What is notable is that women’s IPV was associated with higher levels of child externalizing problems and with higher levels of male IPV. That men’s IPV was not associated with the outcome variables after the other forms of violence were considered may reflect a ceiling effect that is an artifact of our sampling strategy. Although there was variability in the men’s IPV, all of the families had experienced very high levels of male IPV – severe enough to warrant seeking shelter. Consideration of the effects of the various forms of family violence with samples that have broader representation on the IPV variables would be informative. Although using only mother and child reports of the mothers’ and partners’ aggression may have resulted in biased accounts of the family violence, aggregating across mother and child reports of aggression reduces the likelihood of such method variance effects.

Women who seek shelter from IPV face incredible challenges. The present study is not intended to minimize the detrimental effects on children of exposure to men’s violence—or any violence, for that matter—nor is it intended to blame women who are victims of severe violence for their children’s problems. The results of this study should instead draw attention to the fact that all forms of family violence appear to contribute to children’s adjustment problems and to suggest that further investigation into the full spectrum of family violence would be useful and prudent in efforts to understand the influence of family violence on children.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grants R01-MH-53380 and R01-MH-62064 from the National Institute of Mental Health and Grant 2005-JW-BX-K017 awarded by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, Office of Justice Programs, US Department of Justice.

Footnotes

Points of view or opinions in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the US Department of Justice.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4–18 and 1991 Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Appel AE, Holden GW. The co-occurrence of spouse and physical child abuse: A review and appraisal. Journal of Family Psychology. 1998;12:578–599. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social learning theory. Prentice-Hall; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Owen LD. Physical aggression in a community sample of at-risk young couples: Gender comparisons for high frequency, injury, and fear. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15:425–440. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.3.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Dodge KA. A review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in children’s social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;115:74–101. [Google Scholar]

- Crockenberg S, Langrock A. The role of specific emotions in children’s responses to interparental conflict: A test of the model. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15:163–182. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrensaft MK, Moffitt TE, Caspi A. Clinically abusive relationships in an unselected birth cohort: Men’s and women’s participation and developmental antecedents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:258–271. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.2.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantuzzo JW, DePaola LM, Lambert L, Martino T, Anderson G, Sutton S. Effects of interparental violence on the psychological adjustment and competencies of young children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:258–265. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.2.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grych JH, Fincham FD. Marital conflict and children’s adjustment: A cognitive-contextual framework. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:267–290. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grych JH, Fincham FD, Jouriles EN, McDonald R. Interparental conflict and child adjustment: Testing the mediational role of appraisals in the cognitive-contextual framework. Child Development. 2000;71:1648–1661. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grych JH, Seid M, Fincham FD. Assessing marital conflict from the child’s perspective: The Children’s Perception of Interparental Conflict Scale. Child Development. 1992;63:558–572. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes HM, Parkinson D, Vargo M. Witnessing spouse abuse and experiencing physical abuse: A “double whammy”? Journal of Family Violence. 1989;4:197–209. [Google Scholar]

- Jouriles EN. Gaps in our knowledge about the prevalence of children’s exposure to domestic violence and impact of domestic violence on children. Paper presented at a meeting of the National Academy of Sciences; Washington, D.C.. 2000. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- Jouriles EN, Barling J, O’Leary KD. Predicting child behavior problems in maritally violent families. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1987;15:165–173. doi: 10.1007/BF00916346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouriles EN, McDonald R, Norwood WD, Ware HS, Spiller LC, Swank PR. Knives, guns, and interparent violence: Relations with child behavior problems. Journal of Family Psychology. 1998;12:178–194. [Google Scholar]

- Jouriles EN, McDonald R, Slep AMS, Heyman RE, Garrido E. Child abuse in the context of domestic violence: Prevalence, explanations and practice implications. Violence and Victims. 2008;23:221–235. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.23.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouriles EN, McDonald R, Skopp NA. Partner violence and children. In: Pinsof WM, Lebow JL, editors. Family psychology: The art of the science. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2005. pp. 223–242. [Google Scholar]

- Jouriles EN, McDonald R, Spiller L, Norwood WD, Swank PR, Stephens N, Ware H, Buzy WM. Reducing conduct problems among children of battered women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:774–785. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.5.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouriles EN, Mehta P, McDonald R, Francis DJ. Psychometric properties of family members’ reports of parental physical aggression toward clinic-referred children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:309–318. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouriles EN, Norwood WD. Physical aggression toward boys and girls in families characterized by the battering of women. Journal of Family Psychology. 1995;9:69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Jouriles EN, Norwood WD, McDonald R, Peters B. Domestic violence and child adjustment. In: Grych JH, Fincham FD, editors. Interparental conflict and child development: Theory, research, and applications. New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press; 2001. pp. 315–336. [Google Scholar]

- Jouriles EN, Spiller LC, Stephens N, McDonald R, Swank P. Variability in the adjustment of children of battered women: The role of child appraisals of interparent conflict. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2000;24:233–247. [Google Scholar]

- Margolin G, Gordis EB. The effects of family and community violence on children. Annual Review of Psychology. 2000;51:445–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald R, Jouriles EN, Skopp NA. Reducing conduct problems among children brought to women’s shelters: Intervention effects 24 months following termination of services. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:127–136. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meichenbaum D. A clinical handbook/practical therapist manual for assessing and treating adults with post-traumatic stress disorder. Ontario, Canada: Institute Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR. Coercive family process. Eugene, OR: Castalia; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Rossman BR, Rosenberg MS. Family stress and functioning in children: The moderating effects of children’s beliefs about their control over parental conflict. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 1992;33:699–715. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1992.tb00906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slep AMS, O’Leary SG. Parent and partner violence in families with young children: Rates, patterns, and connections. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:435–444. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorenson SB, Upchurch DM, Shen H. Violence and injury in marital arguments: Risk patterns and gender differences. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86:35–40. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg KJ, Lamb ME, Guterman E, Abbott CB. Effects of early and later family violence on children’s behavior problems and depression: A longitudinal, multi-informant perspective. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2006;30:283–306. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The Conflict Tactics (CT) Scales. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1979;41:75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Gelles RJ. Physical violence in American families. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Swan SC, Snow DL. A typology of women’s use of violence in intimate relationships. Violence Against Women. 2002;8:286–319. doi: 10.1177/1077801206293330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White JW, Smith PH, Koss MP, Figueredo AJ. Intimate partner aggression--what have we learned? Comment on Archer (2000) Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126:690–696. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.5.690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe DA, Jaffe P, Wilson SK, Zak L. Children of battered women: The relation of child behavior to family violence and maternal stress. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:657–665. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.5.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe DA, Crooks CV, Lee V, McIntyre-Smith A, Jaffe PG. The effects of children’s exposure to domestic violence: A meta-analysis and critique. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2003;6:171–187. doi: 10.1023/a:1024910416164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]