Abstract

Exposure to inorganic arsenic in utero in C3H mice produces hepatocellular carcinoma in male offspring when they reach adulthood. To help define the molecular events associated with the fetal onset of arsenic hepatocarcinogenesis, pregnant C3H mice were given drinking water containing 0 (control) or 85 ppm arsenic from day 8 to 18 of gestation. At the end of the arsenic exposure period, male fetal livers were removed and RNA isolated for microarray analysis using 22K oligo chips. Arsenic exposure in utero produced significant (p < 0.001) alterations in expression of 187 genes, with approximately 25% of aberrantly expressed genes related to either estrogen signaling or steroid metabolism. Real-time RT-PCR on selected genes confirmed these changes. Various genes controlled by estrogen, including X-inactive-specific transcript, anterior gradient-2, trefoil factor-1, CRP-ductin, ghrelin, and small proline-rich protein-2A, were dramatically over-expressed. Estrogen-regulated genes including cytokeratin 1–19 and Cyp2a4 were over-expressed, although Cyp3a25 was suppressed. Several genes involved with steroid metabolism also showed remarkable expression changes, including increased expression of 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase-7 (HSD17β7; involved in estradiol production) and decreased expression of HSD17β5 (involved in testosterone production). The expression of key genes important in methionine metabolism, such as methionine adenosyltransferase-1a, betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase and thioether S-methyltransferase, were suppressed. Thus, exposure of mouse fetus to inorganic arsenic during a critical period in development significantly alters the expression of various genes encoding estrogen signaling and steroid or methionine metabolism. These alterations could disrupt genetic programming at the very early life-stage, which could impact tumor formation much later in adulthood.

Keywords: Arsenic, in utero exposure, fetal liver, gene expression, estrogen signaling, steroid metabolism

INTRODUCTION

Inorganic arsenic is a human carcinogen, associated with tumors of the skin, urinary bladder, lung, liver, prostate, kidney, and possibly other sites (NRC, 2001; Morales et al., 2000; Centeno et al., 2002; IARC, 2004). We have shown that short-term exposure in mice to inorganic arsenic in utero produces a variety of internal tumors in the offspring when they reach adulthood (Waalkes et al., 2003; 2004a; 2006a, 2006b). Gestation is a period of high sensitivity to chemical carcinogenesis in rodents and probably in humans (Anderson et al., 2000). Inorganic arsenic can readily cross the rodent and human placenta and enter the fetus (Concha et al., 1998; NRC, 2001). After in utero exposure to inorganic arsenic at carcinogenic doses, significant amounts of inorganic arsenic and its methylated metabolites (DMA and MMA) are detected in various mouse fetal tissues including the liver (Devesa et al., 2006). In arsenic-exposed human populations all life stages of exposure are involved (IARC, 2004). Thus, it is likely that significant in utero arsenic exposure occurs in human populations, and it is prudent to assume that the transplacental carcinogenic risks defined in rodents may predict similar effects in humans.

The liver is a major target organ of arsenic toxicity (Lu et al., 2001; Mazumder, 2005) and carcinogenesis in humans (Chen et al., 1997; Zhou et al., 2002; Centeno et al., 2002; Chen and Ahsan, 2004). In accord with human data, transplacental exposure to inorganic arsenic induced a marked, dose-related increase in hepatocellular tumors, including carcinoma, in adult male mice (Waalkes et al., 2003, 2004a, 2006b). Genomic analysis of liver samples taken at necropsy 1–2 years after gestational arsenic exposure alone or combined with postnatal exposure to 12-O-teradecanoyl phorbol-13-acetate (TPA), revealed a variety of hepatic genes to be aberrantly expressed in adulthood, including genes critical to the carcinogenic process (Liu et al., 2004, 2006a, 2006b). Although the expression changes in adult mouse liver are clearly associated with liver tumors, whether they are involved in cancer causation specifically by arsenic cannot be defined in fully developed tumors. Thus, genomic analysis of early molecular events following gestational arsenic exposure is clearly warranted.

The spectrum of tumors and/or proliferative lesions induced by in utero arsenic exposure, including tumors of liver, ovary, adrenal, uterus and oviduct, resembles the potential targets of carcinogenic estrogens (Waalkes et al., 2003; 2004a; 2006a; 2006b). This has led us to the hypothesis that arsenic could somehow produce estrogen-like effects, possibly through estrogen receptor-alpha (ER-α), as part of the mechanisms causing tumor formation (Waalkes et al., 2004b). Aberrant over-expression of ER-α is associated with a variety of human and rodent tumors (Fishman et al., 1995). Indeed, in livers and liver tumors from male mice exposed to arsenic in utero, the over-expression of the ER-α and estrogen-linked cyclin D1 is a prominent feature, and a feminized pattern of hepatic metabolic enzyme genes is evident (Waalkes et al., 2004b; Liu et al., 2004; 2006b). Samples of human livers from populations highly exposed to inorganic arsenic also show ER-α over-expression (Waalkes et al., 2004b).

Thus, this study investigated aberrant gene expression in the fetal male livers following in utero exposure to a hepatocarcinogenic dose of arsenic. Global genomic analysis was performed through the National Center for Toxicogenomics, using the Agilent 22K chip array. Expression of key genes was followed up by real-time RT-PCR analysis. This study clearly showed that in utero arsenic exposure produced dramatic alterations in gene expression in fetal liver, providing evidence for enhanced estrogen signaling and aberrant steroid metabolism in the developing fetus as a result of transplacental arsenic exposure. This arsenic-induced early life stage disruption of genetic programming could potentially lead to tumor formation much later in adulthood.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals

Sodium arsenite (NaAsO2) was obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO) and dissolved in the drinking water at 85 mg arsenic/L (85 ppm). The Agilent 22-K mouse oligo array was obtained from Agilent Technologies (Palo Alto, CA).

Animal Treatment and Sample Collection

Timed pregnant C3H mice were given drinking water containing 85 ppm arsenic or unaltered water ad libitum from day 8 to day 18 of gestation. At day 18 of gestation, mice were killed by CO2 asphyxiation and fetuses removed. Only male fetal livers were used for the present study, as male offspring are most susceptible to arsenic hepatocarcinogenesis (Waalkes et al., 2003, 2004a, 2006b). Animal care was provided in accordance with the US Public Health Policy on the Care and Use of Animals, and the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved this study proposal. Animals used in this study were treated humanely and with regard for the alleviation of suffering.

Microarray Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from liver samples with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), followed by purification and on-column DNase-I digestion with RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The high quality of RNA was confirmed by an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA). Total RNA was amplified using the Agilent Low RNA Input Fluorescent Linear Amplification Kit protocol. Starting with 500 ng of total RNA, Cy3 or Cy5 labeled cRNA was produced according to manufacturer’s protocol. For each two-color comparison, 750 ng of each Cy3 and Cy5 labeled cRNAs were mixed and fragmented using the Agilent In Situ Hybridization Kit protocol. Hybridizations were performed on Agilent mouse 22K oligo assay for 17 hours in a rotating hybridization oven using the Agilent 60-mer oligo microarray processing protocol. Slides were washed as indicated in this protocol and then scanned with an Agilent Scanner. Data were obtained using the Agilent Feature Extraction software (v7.5), using defaults for all parameters. Two hybridizations with fluor reversals were performed for each RNA sample from each group.

Real-time RT-PCR Analysis

The levels of expression of the selected genes were quantified using real-time RT-PCR analysis. The forward and reverse primers for selected genes were designed using ABI Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and listed in Table 1. Total RNA was reverse transcribed with MuLV reverse transcriptase and oligo-dT primers, and subjected to real-time PCR analysis using SYBR green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems, Cheshire, UK). The cycle time (Ct) values of genes of interest were first normalized with β-actin from the same sample, and then the relative differences between control and treatment groups were calculated and expressed as percentage of controls. Assuming that the Ct value is reflective of the initial starting copy and that there is 100% efficiency, a difference of one cycle is equivalent to a two-fold difference in starting copy.

Table 1.

Primer sequences for real-time RT-PCR analysis

| Gene name | Acceession # | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agr2, anterior gradient 2 | NM_011783 | CCTTGCGGCTCACACAAAG | ATGGCCACAAGAAGCAGGAT |

| Akr1c18 | NM_134066 | GCAACCAGGTAGAATGCCATCT | GCACCATAGGCAACCAGAACA |

| β-actin | M12481 | GTATGACTCCACTCACGGCAAA | GGTCTCGCTCCTGGAAGATG |

| Bhmt | AF033381 | CACATCAGGGCGATTGCA | TCCCCAGCTGCCATGTTT |

| Cbg (corticocoid-binding protein) | NM_007618 | CCATGCTGCAACTGGATGAA | GATTCGGAGGGCAGGTGTAC |

| CRP-ductin (Dmbt1) | NM_007769 | GCCAACCTCCAAGTACTAAGTTGTG | GTCAGGCTCTCATGTCTTCCATCT |

| Cyp2a4 | J03549 | GGAAGACGAACGGTGCTTTC | CCCGAAGACGATTGAGCTAATG |

| Cyp2j5 | NM_010007 | CAGACATGGAAGGAGCAAAGG | GAATGCGCTCCTCCAAGCT |

| Cyp3a25 | Y11995 | TGGAGGCCTGAACTGCTAAAG | TAACCAGCAGCACCCAGGTT |

| HSD11β1 | NM_008288 | CTCTCTTCCATGACGACATCCA | CTGTGCTCATGACCACGTAGCT |

| HSD17β5 (Akr1c6) | NM_030611 | GCCATGGAGAAATGCAAGGA | GTTGCACACAGGCTTGTACTTGAG |

| HSD17β7 | NM_010476 | AGCTGATGGAGGCGTTCCT | TGTGTATCACCCAGCGAGATG |

| Krt1-19 | NM_008471 | GAGGACTTGCGCGACAAGA | GGCGAGCATTGTCAATCTGTAG |

| Mat1a | NM_133653 | CAGGTGTCCTATGCCATTGGT | TCTAGCAGCTCCCGCTCAGT |

| Sprr2a (samll proline-rich protein 2A) | NM_011468 | GGGAAGCACAACAGGTATCTACTCT | GCAGTGACCATTGCCCTGAT |

| Temt (thioether S-methyltransferase) | NM_009349 | CCTACGACTGGTCCTCCATAGTG | CTTCTGAGCTTGGCTTCCTTCT |

| Tff1 | NM_009362 | GGCCCAGGAAGAAACATGTATC | CCCCGGACACTGTCATCAA |

| XIST | L04961 | GCTTCTGCGTGATACGGCTAT | AGCTAGCGCAGCGCAATT |

Statistics

For microarray analysis, samples were cross-hybridized with Cy3 and Cy5. Images and GEML files, including error and p-values, were exported from the Agilent Feature Extraction software and deposited into the Rosetta Resolver system (version 4.0, build 4.0.1.0.7.RSPLIT) (Rosetta Biosoftware, Kirkland, WA). The resultant ratio profiles were combined. Intensity plots were generated for each ratio experiment and genes were considered “signature genes” if the p value was less than 0.001. For real-time RT-PCR analysis, means and SEM of individual samples (n = 6) were calculated. For the comparisons of gene expression between two groups, Students’ t tests were performed.

RESULTS

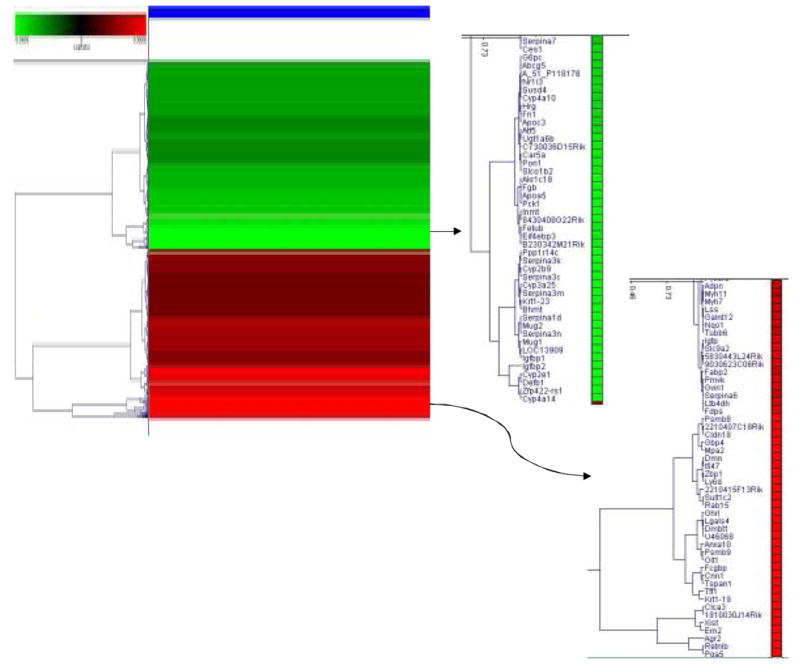

Microarray analysis of aberrantly expressed genes

Total RNA from male fetal liver samples of control and arsenic-exposed mice were subjected to microarray analysis. Under the criteria of p < 0.001 by the Rosetta Resolver (v4.0) system, the transcript levels of 187 genes among 22,000 contained on the array were significantly altered by arsenic exposure compared to control. Clustering analysis of these altered genes is shown in Fig. 1. A cluster of increased genes (shown in red) included various genes related to estrogen signaling, and a cluster of decreased genes (shown in green) included various metabolic enzymes (Fig. 1). The 30 genes with increased expressions (cut-off at ratio of 1.9) are listed in Table 2, and 30 genes with decreased expressions (cut-off at ratio of 0.65) are listed in Table 3. The putative cDNA clones without fully defined corollary genes are excluded from this list.

Figure 1.

Altered gene expression in fetal mouse liver exposed to arsenic in utero. The significantly altered genes under criteria of p < 0.001 were clustered for comparison. The increased genes are shown in red, and the decreased genes are shown in green.

Table 2.

Microarray analysis of increased gene expression in arsenic-exposed fetal mouse liver

| Symbol | Accession | Gene Description | Control | Arsenic | As/Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agr2 | NM_011783 | anterior gradient 2 (Xenopus laevis) | 133 | 3004 | 22.80 |

| Pga5 | NM_021453 | Mus musculus pepsinogen 5, group I (Pga5), mRNA. | 702 | 11166 | 15.77 |

| Retnlb | NM_023881 | resistin like beta | 62 | 893 | 15.43 |

| Clca3 | NM_017474 | chloride channel calcium activated 3 | 258 | 1903 | 7.47 |

| Xist | L04961 | inactive X specific transcripts | 182 | 1195 | 6.68 |

| Ern2 | NM_012016 | endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to nucleus signalling 2 | 163 | 927 | 6.04 |

| Krt1-19 | NM_008471 | keratin complex 1, acidic, gene 19 | 368 | 1794 | 4.87 |

| Tff1 | NM_009362 | trefoil factor 1 | 1191 | 5127 | 4.30 |

| Tspan1 | NM_133681 | Mus musculus tetraspan 1 (Tspan1), mRNA | 162 | 600 | 3.78 |

| Cnn1 | NM_009922 | calponin 1 | 867 | 3191 | 3.71 |

| Mtlrp(Ghrl) | NM_021488 | motilin-related peptide | 73 | 266 | 3.54 |

| Crpd | NM_007769 | crp-ductin | 281 | 907 | 3.44 |

| Lgals4 | BC011236 | Mus musculus galactose binding, soluble 4 (Galectin-4) | 450 | 1540 | 3.41 |

| U46068 | U46068 | Mus musculus von Ebner minor salivary gland protein mRNA | 461 | 1558 | 3.39 |

| Anxa10 | AK020288 | annexin A10 | 398 | 1260 | 3.17 |

| Psmb9 | NM_013585 | proteosome (prosome, macropain) subunit, beta type 9 | 1724 | 5270 | 3.05 |

| AK010206 | AK010206 | oncoprotein induced transcript 1, full insert sequence | 365 | 1049 | 2.95 |

| Cldn18 | NM_019815 | claudin 18 | 324 | 890 | 2.91 |

| Psmb8 | NM_010724 | proteosome (prosome, macropain) subunit, beta type 8 | 1849 | 5301 | 2.86 |

| Mpa2 | NM_008620 | macrophage activation 2 | 348 | 953 | 2.75 |

| Gbp3 | NM_018734 | guanylate nucleotide binding protein 3 | 773 | 1996 | 2.58 |

| Sult1c1 | NM_026935 | Mus musculus sulfotransferase family,1C, member 1 (Sult1c1) | 361 | 778 | 2.19 |

| Dlm1 (Zbp1) | NM_021394 | tumor stroma and activated macrophage protein DLM-1 | 550 | 1173 | 2.13 |

| Ly6d | NM_010742 | lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus D | 314 | 667 | 2.11 |

| Scyb10 | NM_021274 | small inducible cytokine B subfamily (Cys-X-Cys), member 10 | 688 | 1426 | 2.10 |

| Ifi47 | NM_008330 | interferon gamma inducible protein, 47 kDa | 1689 | 3538 | 2.09 |

| Iigp | NM_021792 | interferon-inducible GTPase | 14068 | 29009 | 2.05 |

| Krt1-15 | NM_008469 | keratin complex 1, acidic, gene 15 | 494 | 999 | 2.04 |

| Tacstd1 | NM_008532 | tumor-associated calcium signal transducer 1 | 1228 | 2452 | 2.01 |

| Sprr2a | NM_011468 | small proline-rich protein 2A | 800 | 1528 | 1.93 |

Table 3.

Microarray analysis of decreased gene expression in arsenic-exposed fetal mouse liver

| Symbol | Accession | Gene Description | Control | Arsenic | As/Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Igfbp2 | NM_008342 | insulin-like growth factor binding protein 2 | 17969 | 5581 | 0.31 |

| Cyp2e1 | NM_021282 | cytochrome P450, 2e1, ethanol inducible | 13706 | 5259 | 0.38 |

| Defb1 | NM_007843 | defensin beta 1 | 578 | 229 | 0.38 |

| Cyp4a14 | NM_007822 | cytochrome P450, 4a14 | 16593 | 6851 | 0.41 |

| Igfbp1 | NM_008341 | insulin-like growth factor binding protein 1 | 438719 | 186169 | 0.43 |

| Est31 | NM_144511 | esterase 31, male-predominant carboxylesterase in mouse liver | 8808 | 3835 | 0.44 |

| Mug1 | NM_008645 | murinoglobulin 1 | 1313 | 595 | 0.45 |

| Spi2-2 | NM_009252 | serine protease inhibitor 2-2 | 44864 | 20661 | 0.46 |

| Mug-ps1 | M65237 | Mouse murinoglobulin (MUG3) mRNA, last 2 exons | 508 | 246 | 0.46 |

| Spi1-4 | NM_009246 | serine protease inhibitor 1–4 | 1102183 | 512408 | 0.46 |

| Spi2 | D00725 | serine protease inhibitor 2 | 4930 | 2346 | 0.47 |

| Klkbp | AI115771 | kallikrein binding protein | 23838 | 11520 | 0.48 |

| Bhmt | NM_016668 | betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase | 12196 | 6020 | 0.49 |

| Cyp2b9 | NM_010000 | cytochrome P450, 2b9, phenobarbitol inducible, type a | 1120 | 546 | 0.49 |

| Haik1 | NM_033373 | type I intermediate filament cytokeratin | 1903 | 935 | 0.49 |

| Cyp3a25 | Y11995 | cytochrome P450, 3a25 | 2707 | 1366 | 0.50 |

| Spi2-rs1 | NM_009253 | serine protease inhibitor-2 related sequence 1 | 29480 | 14887 | 0.51 |

| Akr1c18 | NM_134066 | Mus musculus aldo-keto reductase family 1, member C18 (Akr1c18) | 769 | 390 | 0.51 |

| Pck1 | NM_011044 | phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 1, cytosolic | 17597 | 9190 | 0.52 |

| Temt | NM_009349 | thioether S-methyltransferase | 1262 | 694 | 0.55 |

| Fetub | NM_021564 | fetuin beta | 30806 | 17606 | 0.56 |

| Slc21a10 | NM_020495 | solute carrier family 21 (organic anion transporter), member 10 | 35255 | 20890 | 0.59 |

| Pon1 | NM_011134 | paraoxonase 1 | 22003 | 13048 | 0.59 |

| Car5a | NM_007608 | carbonic anhydrase 5a, mitochondrial | 2063 | 1226 | 0.59 |

| Ugt1a1 | S64760 | UGTBr1=UDP-glucuronosyltransferase [mice, mRNA, 2215 nt]. | 48324 | 28752 | 0.60 |

| Cyp4a10 | AK002528 | cytochrome P450, 4a10 | 1255 | 768 | 0.61 |

| Fn1 | X93167 | M. musculus mRNA for fibronectin. | 23405 | 14628 | 0.62 |

| Cyp2f2 | NM_007817 | cytochrome P450, 2f2 | 11356 | 7185 | 0.63 |

| Hsd11b1 | NM_008288 | hydroxysteroid 11-beta dehydrogenase 1 | 17620 | 11266 | 0.64 |

| Cyp2j5 | NM_010007 | cytochrome P450, 2j5 | 2319 | 1511 | 0.65 |

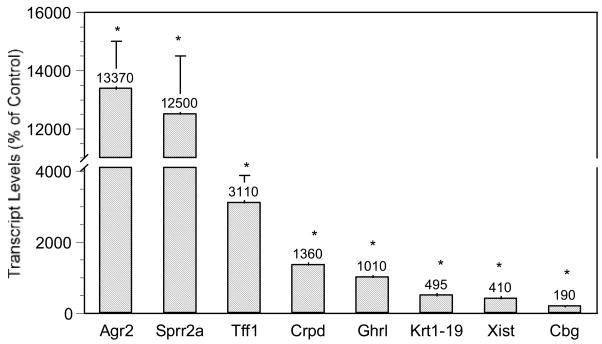

Real-time RT-PCR analysis of aberrantly expressed genes

To help verify the microarray results, real-time RT-PCR analysis of selected genes was performed using individual samples from control and arsenic-exposed male fetal livers. Real-time RT-PCR generally confirmed microarray results, although RT-PCR appeared to be more sensitive and often showed more pronounced changes than microarray analysis. For consistency, quantitative description and discussion are henceforth based on the real-time RT-PCR analysis. For genes potentially regulated by estrogen (Fig. 2), there were marked increases in anterior gradient 2 (Agr2, 134-fold), small proline-rich protein 2a (Sprr2a, 125-fold), trefoil factor 1 (Tff1, 31-fold), CRP-ductin (14-fold), ghrelin (Ghrl, 10-fold), cytokeratin 1–19 complex (Krt1-19, 5-fold), X-inactive specific transcript (Xist, 4-fold), and corticosteroid-binding globulin (Cbg, 2-fold).

Figure 2.

Effect of in utero arsenic exposure on estrogen-signaling gene expression in the fetal liver. Data are mean + SEM of 6 mice. *Significantly different from controls, p < 0.05.

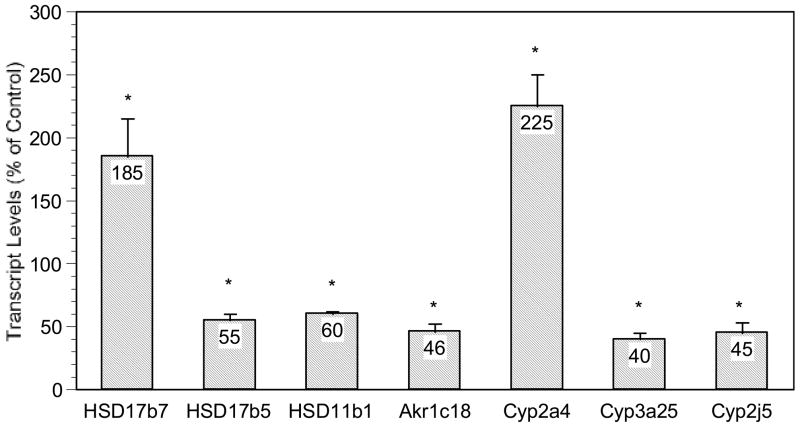

Figure 3 illustrates the altered expression of genes related to steroid metabolism. These included increased expression of hydroxysteroid 11-β dehydrogenase-7 (HSD17β7, 1.9-fold, involved in estradiol production) and decreased expression of HSD17β5 (0.52 ratio to control, involved in testestorone production), HSD11β1 (0.58 ratio to control) and aldo-keto reductase Akr1c18 (also known as 20α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, 0.46 ratio to control). For sex-dependent cytochrome P450 enzyme genes, the expression of female dominant Cyp2a4 (steroid 15α-hydroxylase) was increased 2.3 fold, while the expression of male dominant Cyp3a25 (0.40 ratio to control) and Cyp2j5 (0.45 ratio to control) were decreased.

Figure 3.

Effect of in utero arsenic exposure on expression of genes related to steroid metabolism in the fetal liver. Data are mean + SEM of 6 mice. *Significantly different from controls, p < 0.05.

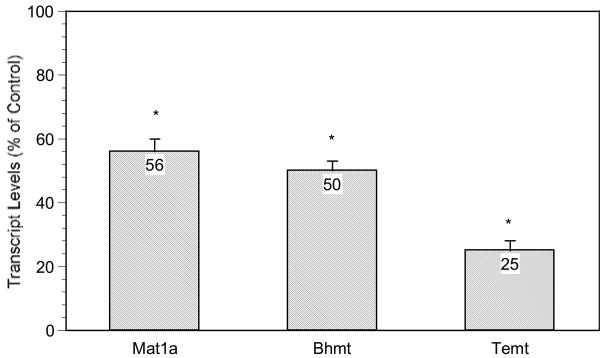

The expression of several genes involved in methyl metabolism in fetal male mouse liver were also decreased (Fig. 4). These include methionine adenosyltransferase 1a (Mta1a; 0.56 ratio to control), betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase (Bhmt; 0.50 ratio to control) and thioether S-methyltransferase (Temt; 0.25 ratio to control).

Figure 4.

Effect of in utero arsenic exposure on expression of genes related to methyl metabolism in the fetal liver. Data are mean + SEM of 6 mice. *Significantly different from controls, p < 0.05.

Discussion

The hypothesis that inorganic arsenic might somehow act through aberrant activation of estrogen signaling pathways (Waalkes et al., 2004b) comes from several lines of evidence. This includes the fact that the transplacental arsenic carcinogenesis shows consistent targets (i.e., liver, ovary, adrenal, uterus) which are also targets of broad range or tissue-selective carcinogenic estrogens (Birnbaum and Fenton, 2003; Newbold, 2004). In addition, estrogen-linked gene/protein overexpressions are evident in transplacental arsenic-induced tumors (Waalkes et al., 2004b, 2006a; Liu et al., 2004, 2006a, 2006b; Shen et al., 2007). Furthermore, transplacental arsenic enhances subsequent diethylstilbestrol (a synthetic estrogen) carcinogenesis (Waalkes et al., 2006a, 2006b) and enhances diethylstilbestrol-induced estrogen-related gene expression in neonatal tissues (Waalkes et al., 2006a). For instance, compared to the incidence of urogenital cancers in the control (0%), arsenic (9%), or diethystilbestrol (21%) alone, in utero arsenic plus postnatal diethylstilbestrol induces a synergistic 48% increase in urogenital malignancies (Waalkes et al., 2006a). Transplacental arsenic-induced lung tumorigenesis is associated with aberrant expression of pulmonary estrogen-related genes in the fetus (Shen et al., 2007). The current study demonstrates various estrogen-linked genes (such as Xist, Agr2, Tff1, CRP-ductin, Ghrl, Krt1-19, and Cyp2a4) were significantly over-expressed in fetal livers following in utero arsenic exposure, adding further evidence to support the hypothesis that aberrant estrogen signaling may play a role in transplacental arsenic carcinogenesis in mice.

Xist is a female specific gene essential for X-chromosome inactivation in female mammals (Goto and Monk, 1998; Plath et al., 2002). The expression of Xist was increased nearly 4-fold in arsenic-exposed male fetal livers. Epigenetic dynamics of imprinted X chromosome inactivation during early development is a critically important process for early genetic programming and development in mice and in humans (Goto and Monk, 1998; Okmoto et al., 2004). Xist is imprinted early in mammalian development (Okmoto et al., 2004). Aberrant regulation of Xist could lead to disruption of cell differentiation and could have implications in early life programming (Plath et al., 2002; Okmoto et al., 2004), and deserves further investigation.

Anterior gradient 2 (Agr2) expression was dramatically increased (140-fold) in arsenic-exposed fetal livers. Agr2 mRNA and protein are positively associated with ER-α positive, but not ER-α negative, breast carcinomas (Liu et al., 2005). In human breast cancer, Agr2 and Krt1-19, both estrogen-regulated genes, are over-expressed (Shen et al., 2005). Estrogen-linked trefoil factor 1 (Tff1) and CRP-ductin expression was increased 32- and 15-fold, respectively, in arsenic-exposed fetal livers. Estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer cells secrete high concentrations of Tff1, and dimeric Tff1 is a potent stimulator for migration of breast cancer cells (Prest et al., 2002). Tff1 is also required for the commitment programming of mouse oxyntic epithelial progenitors, and influences Tff2 and Tff3 expression during development (Kama et al., 2004). In mouse uterine adenocarcinoma and urinary bladder transitional cell carcinoma induced by in utero arsenic plus postnatal diethylstilbestrol treatment, ER-α and pS2 (Tff1) and were greatly over-expressed (Waalkes et al., 2006a). CRP-ductin fulfils some of the criteria for being a Tff receptor or a Tff binding protein (Thim and Mortz, 2000), and is an estrogen-responsive gene with a possible role in endometrial proliferation or differentiation. Ghrelin and small proline-rich protein 2a (Sprr2a) were increased 13- and 120-fold, respectively, in arsenic-exposed fetal livers. Ghrelin plays an important role in the control of some aspects of gonadal function in the testes and ovary (Tena-Sempere, 2005), and its expression is regulated by estrogen (Tena-Sempere, 2005). Ghrelin immunopositive cells also express ER-α (Matsubara et al., 2004). Similarly, expression of Sprr2 protein and the Sprr2 mRNA family (Sprr2a, 2b, 2c, 2d, 2e, 2f, and 2g) can be regulated by estrogen, and Sprr2a has been proposed to play a role in the estrous cycle, early pregnancy and implantation (Hong et al., 2004). Most of the above genes have cross-talk mechanisms with ER-α (Hewitt et al., 2005). The aberrant over-expression of these genes in fetal liver supports an early disruption by arsenic of estrogen signaling.

Possibly as a contributing factor in aberrant estrogen signaling, the genes encoding steroid metabolism enzymes were also altered. For example, the expression of HSD17β7, a gene encoding for an enzyme involved with estradiol biosynthesis (Nokelainen et al., 1998), was increased ~2 fold, while the expression of HSD17β5, a gene encoding for an enzyme catalyzing the transformation of 4-androstenedione (4-dione) into testosterone (Luu-The et al., 2001), was decreased ~50%. Enhanced expression of female-dominant Cyp2a4 and the decreased expression of male-dominant Cyp2j5 and Cyp3a25 were also evident in arsenic-exposed fetal livers. Cyp2a4 (steroid 15α-hydroxylase) is an ER-α-regulated gene (Sueyoshi et al., 1999), Cyp3a25 encodes for a testosterone 6β-hydroxylase (Dai et al., 2001), and the expression of Cyp2j5 is up-regulated by androgen and down-regulated by estrogen (Ma et al., 2005). In addition, the expression of HSD11β1 and Akr1c18 were both decreased ~50% in arsenic-exposed fetal livers. HSD11β1 converts inactive cortisone to active cortisol (Tomlinson et al., 2004) and Akr1c18 encodes 20α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (Vergnes et al., 2003). Thus, alterations in the expression of these genes are reflective of endocrine disruption effects of inorganic arsenic at a very early life stage. The fetal stage is a critical period of development which is susceptible to environmental estrogen insult (Birnbaum and Fenton, 2003). The impact of arsenic in fetal livers is quite similar to the liver feminization pattern seen in arsenic-induced hepatocellular carcinomas occurring much later in life (Waalkes et al., 2004b, Liu et al., 2004, 2006a, 2006b).

Another interesting category of aberrant gene expression after in utero arsenic is related to methionine metabolism. The expression of methionine adenosyltransferase 1(Mta1a), betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase (Bhmt) and thioether S-methyltransferase (Temt), were decreased in arsenic-exposed fetal livers. The aberrant expression of these enzyme genes would potentially contribute to abnormal S-adenosylmethionine production, a critical methyl donor for enzymatic DNA methylation. Altered methyl group metabolism could provide a potential mechanism for inducing epigenetic changes in the embryo (Steele et al., 2005), including DNA methylation changes, as DNA methylation is an important gene imprinting mechanism during development and can be altered in the adult during arsenic carcinogenesis (Chen et al., 2004; Waalkes et al., 2004b)

In summary, the present study clearly demonstrates that in utero arsenic exposure resulted in dramatic alterations in gene expression in the fetal liver involving a complex interplay between steroid metabolism and estrogen signaling pathways, which may well play an important role in early genetic reprogramming, leading to the formation of tumors later in life (Cook et al., 2005). As a corollary in humans, increased mortality occurs from lung cancers in young adults following in utero exposure to arsenic in the drinking water (Smith et al., 2006). Thus, the developing human and mouse fetus appear to be very sensitive to arsenic carcinogenesis. Reduction of arsenic intake in pregnant women may be a valid mechanism for reducing human cancer associated with environmental arsenic exposure.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Erik Tokar, Ronald Cannon and Larry Keefer for their critical review of this manuscript. Research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research, the Federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contract No. NO1-CO-12400, and the National Center for Toxicogenomics at NIEHS. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anderson LM, Diwan BA, Fear NT, Roman E. Critical windows of exposure for children’s health: cancer in human epidemiological studies and neoplasms in experimental animal models. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108(suppl 3):573–594. doi: 10.1289/ehp.00108s3573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum LS, Fenton SE. Cancer and developmental exposure to endocrine disruptors. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:389–394. doi: 10.1289/ehp.5686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centeno JA, Mullick FG, Martinez L, Page NP, Gibb H, Longfellow D, Thompson C, Ladich ER. Pathology related to chronic arsenic exposure. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110(Suppl 5):883–886. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110s5883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CJ, Yu MW, Liaw YF. Epidemiological characteristics and risk factors of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997;12:S294–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1997.tb00513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Li S, Liu J, Diwan BA, Barrett JC, Waalkes MP. Chronic inorganic arsenic exposure induces hepatic global and individual gene hypomethylation: implications for arsenic hepatocarcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:1779–1786. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Ahsan H. Cancer burden from arsenic in drinking water in Bangladesh. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:741–744. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.5.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Concha G, Vogler G, Lezcano D, Nermell B, Vahter M. Exposure to inorganic arsenic metabolites during early human development. Toxicol Sci. 1998;44:185–190. doi: 10.1006/toxs.1998.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook JD, Davis BJ, Cai SL, Barrett JC, Conti CJ, Walker CL. Interaction between genetic susceptibility and early life environmental exposure determines tumor suppressor gene penetrance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:8644–8649. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503218102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai D, Bai R, Hodgson E, Rose RL. Cloning, sequencing, heterologous expression, and characterization of murine cytochrome P450 3a25*(Cyp3a25), a testosterone 6beta-hydroxylase. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2001;15:90–99. doi: 10.1002/jbt.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devesa V, Adair BM, Liu J, Waalkes MP, Diwan BA, Styblo M, Thomas DJ. Speciation of arsenic in the maternal and fetal mouse tissues following gestational exposure to arsenite. Toxicology. 2006;224:147–155. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2006.04.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman J, Osborne MP, Telang NT. The role of estrogen in mammary carcinogenesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1995;768:91–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb12113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt SC, Collins J, Grissom S, Deroo B, Korach KS. Global uterine genomics in vivo: microarray evaluation of the estrogen receptor alpha-growth factor cross-talk mechanism. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:657–668. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong SH, Nah HY, Lee JY, Lee YJ, Lee JW, Gye MC, Kim CH, Kang BM, Kim MK. Estrogen regulates the expression of the small proline-rich 2 gene family in the mouse uterus. Mol Cells. 2004;17:477–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto T, Monk M. Regulation of X-chromosome inactivation in development in mice and humans. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:362–378. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.2.362-378.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IARC (Intermational Agency for Research on Cancer) Arsenic in drinking water. Some Drinking Water Disinfectants and Contaminants, including Arsenic. Vol. 84. Lyon, France: IARC; 2004. IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans; pp. 269–477. [Google Scholar]

- Karam SM, Tomasetto C, Rio MC. Trefoil factor 1 is required for the commitment programme of mouse oxyntic epithelial progenitors. Gut. 2004;53:1408–1415. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.031963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Rudland PS, Sibson DR, Platt-Higgins A, Barraclough R. Human homologue of cement gland protein, a novel metastasis inducer associated with breast carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3796–3805. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Xie Y, Ward JM, Diwan BA, Waalkes MP. Toxicogenomic analysis of aberrant gene expression in liver tumors and nontumorous livers of adult mice exposed in utero to inorganic arsenic. Toxicol Sci. 2004;77:249–257. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfh055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Xie Y, Ducharme DMK, Shen J, Diwan BA, Merrick BA, Grissom SF, Tucker CJ, Paules PS, Tennant R, Waalkes MP. Global gene expression associated with hepatocarcinogenesis in adult male mice induced by in utero arsenic exposure. Environ Health perspect. 2006a;114:404–411. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Xie Y, Merrick BA, Shen J, Ducharme DMK, Collins J, Diwan BA, Logsdon D, Waalkes MP. Transplacental arsenic plus postnatal 12-O-teradecanoyl phorbol-13-acetate exposures induced similar aberrant gene expressions in male and female mouse liver tumors. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2006b;213:216–223. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu T, Liu J, LeCluyse EL, Zhou YS, Cheng ML, Waalkes MP. Application of cDNA microarray to the study of arsenic-induced liver diseases in the population of Guizhou, China. Toxicol Sci. 2001;59:185–192. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/59.1.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luu-The V, Dufort I, Pelletier G, Labrie F. Type 5 17beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase: its role in the formation of androgens in women. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2001;171:77–82. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(00)00425-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Graves J, Bradbury JA, Zhao Y, Swope DL, King L, Qu W, Clark J, Myers P, Walker V, Lindzey J, Korach KS, Zeldin DC. Regulation of mouse renal CYP2J5 expression by sex hormones. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65:730–743. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.3.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara M, Sakata I, Wada R, Yamazaki M, Inoue K, Sakai T. Estrogen modulates ghrelin expression in the female rat stomach. Peptides. 2004;25:289–297. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2003.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazumder DN. Effect of chronic intake of arsenic-contaminated water on liver. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;206:169–175. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales KH, Ryan L, Kuo T-L, Wu M-M, Chen C-J. Risk of internal cancers from arsenic in the drinking water. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108:655–661. doi: 10.1289/ehp.00108655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newbold RR. Lessons learned from perinatal exposure to diethylstilbestrol. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2004;199:142–150. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2003.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nokelainen P, Peltoketo H, Vihko R, Vihko P. Expression cloning of a novel estrogenic mouse 17 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase/17-ketosteroid reductase (m17HSD7), previously described as a prolactin receptor-associated protein (PRAP) in rat. Mol Endocrinol. 1998;12:1048–1059. doi: 10.1210/mend.12.7.0134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NRC (National Research Council) Arsenic in the drinking water (update) NRC, National Academy; Washington, DC: 2001. pp. 1–225. [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto I, Otte AP, Allis CD, Reinberg D, Heard E. Epigenetic dynamics of imprinted X inactivation during early mouse development. Science. 2004;303:644–649. doi: 10.1126/science.1092727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plath K, Mlynarczyk-Evans S, Nusinow DA, Panning B. Xist RNA and the mechanism of X chromosome inactivation. Annu Rev Genet. 2002;36:233–278. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.36.042902.092433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prest SJ, May FE, Westley BR. The estrogen-regulated protein, TFF1, stimulates migration of human breast cancer cells. FASEB J. 2002;16:592–594. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0498fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen D, Chang HR, Chen Z, He J, Lonsberry V, Elshimali Y, Chia D, Seligson D, Goodglick L, Nelson SF, Gornbein JA. Loss of annexin A1 expression in human breast cancer detected by multiple high-throughput analyses. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;326:218–227. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.10.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J, Liu J, Xie Y, Diwan BA, Waalkes MP. Fetal onset of aberrant gene expression relevant to pulmonary carcinogenesis in lung adenocarcinoma development induced by in utero arsenic exposure. Toxicol Sci. 2007;95:313–320. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfl151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AH, Marshall G, Yuan Y, Ferreccio C, Liaw J, von Ehrenstein O, Steinmaus C, Bates MN, Selvin S. Increased mortality from lung cancer and bronchiectasis in young adults after exposure to arsenic in utero and in early childhood. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114:1293–1296. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele W, Allegrucci C, Singh R, Lucas E, Priddle H, Denning C, Sinclair K, Young L. Human embryonic stem cell methyl cycle enzyme expression: modeling epigenetic programming in assisted reproduction? Reprod Biomed Online. 2005;10:755–766. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)61120-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun JM, Spencer VA, Li L, YuChen H, Yu J, Davie JR. Estrogen regulation of trefoil factor 1 expression by estrogen receptor alpha and Sp proteins. Exp Cell Res. 2005;302:96–107. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tena-Sempere M. Exploring the role of ghrelin as novel regulator of gonadal function. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2005;15:83–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ghir.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thim L, Mortz E. Isolation and characterization of putative trefoil peptide receptors. Regul Pept. 2000;90:61–68. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(00)00110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson JW, Walker EA, Bujalska IJ, Draper N, Lavery GG, Cooper MS, Hewison M, Stewart PM. 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1: a tissue-specific regulator of glucocorticoid response. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:831–866. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergnes L, Phan J, Stolz A, Reue K. A cluster of eight hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase genes belonging to the aldo-keto reductase supergene family on mouse chromosome 13. J Lipid Res. 2003;44:503–511. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M200399-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waalkes MP, Ward JM, Liu J, Diwan BA. Transplacental carcinogenicity of inorganic arsenic in the drinking water: induction of hepatic, ovarian, pulmonary, and adrenal tumors in mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2003;186:7–17. doi: 10.1016/s0041-008x(02)00022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waalkes MP, Ward JM, Diwan BA. Induction of tumors of the liver, lung, ovary and adrenal in adult mice after brief maternal gestational exposure to inorganic arsenic: promotional effects of postnatal phorbol ester exposure on hepatic and pulmonary, but not dermal cancers. Carcinogenesis. 2004a;25:133–141. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgg181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waalkes MP, Liu J, Chen H, Xie Y, Achanzar WE, Zhou YS, Cheng ML, Diwan BA. Estrogen signaling in livers of male mice with hepatocellular carcinoma induced by exposure to arsenic in utero. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004b;96:466–474. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waalkes MP, Liu J, Ward JM, Powell DA, Diwan BA. Urogenitial system cancers in female CD1 mice induced by in utero arsenic exposure are exacerbated by postnatal diethylstilbestrol treatment. Cancer Res. 2006a;66:1337–1445. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waalkes MP, Liu J, Ward JM, Diwan BA. Tumors and proliferative lesions of liver, urinary bladder, adrenal, lung, and kidney in male CD1 mice after transplacental exposure to inorganic arsenic and postnatal treatment with diethylstilbestrol or tamoxifen. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2006b;215:295–305. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou YS, Du H, Cheng M-L, Liu J, Zhang XJ, Xu L. The investigation of death from diseases caused by coal-burning type of arsenic poisoning. Chin J Endemiol. 2002;21:484–448. [Google Scholar]