Abstract

The eosinophil-derived neurotoxin (EDN, also known as eosinophil protein-X) is best-known as one of the four major proteins found in the large specific granules of human eosinophilic leukocytes. Although it was named for its discovery and initial characterization as a neurotoxin, it is also expressed constitutively in human liver tissue and its expression can be induced in macrophages by proinflammatory stimuli. EDN and its divergent orthologs in rodents have ribonuclease activity, and are members of the extensive RNase A superfamily, although the relationship between the characterized physiologic functions and enzymatic activity remains poorly understood. Recent explorations into potential physiologic functions for EDN have provided us with some insights into its role in antiviral host defense, as a chemoattractant for human dendritic cells, and most recently, as an endogenous ligand for toll-like receptor (TLR)2.

Keywords: Inflammation, Ribonuclease, Toll-like receptor, Dendritic cell, Leukocyte

Introduction

The eosinophil-derived neurotoxin (EDN) is one of the four major proteins found in the cytoplasmic granules of human eosinophilic leukocytes (Fig. 1), cells that are mobilized from the bone marrow to the blood and tissues in response to Th2 stimuli characteristic of allergic inflammation and parasitic helminth infection [1]. The purification and initial characterization of EDN as a neurotoxin will be reviewed, and the more recent findings focusing on EDN in innate immunity will be covered in specific detail. Of particular note is the very recent finding that EDN can initiate signal transduction via interaction with the pattern recognition receptor, toll-like receptor (TLR)-2 [2], as this finding may ultimately provide some much-needed connection between what has until now been separate realms of investigation on this intriguing protein.

Fig. 1. Human eosinophilic leukocytes.

EDN is a major secretory protein stored in the prominent cytoplasmic granules, shown here. These cells were stained with a modified Giemsa preparation (Dade Behring AG, Dudingen, Switzerland, original magnification 63X). Reprinted with permission from [48].

Discovery, Purification and Initial Characterization of EDN

In the 1930s, M. H. Gordon described a neurotoxic syndrome resulting from intracerebral injection of a human lymph node suspension into rabbits which emerged as part of his search for an infectious etiology for Hodgkin's disease [3]. Ultimately, the source of the neurotoxicity proved to be the infiltrating eosinophils [4], and one of the two neurotoxic components, a protein of MW ∼18 kDa that reproduced the Gordon phenomenon when injected intrathecally into rabbits or guinea pigs at microgram quantitites, was isolated by both Durack and colleagues [5], who named their protein the eosinophil-derived neurotoxin and Peterson and Venge [6], who named their protein eosinophil-protein X (EPX). EDN and EPX have since been evaluated side-by-side and are clearly the same protein [7]; both names persist in the literature, we will use EDN here for simplicity's sake. EDN is unique among the major eosinophil granule proteins for its relatively low cationicity; its isoelectric point is ∼9, much lower than that of the other granule proteins counterparts, eosinophil cationic protein (ECP), major basic protein (MBP), and eosinophil peroxidase (EPO), all with isoelectric points of ∼11. As such, in tissue culture assays of cytotoxicity and in vitro assays of helminth toxicity, EDN has relatively little activity when compared to the other granule proteins [8 - 11].

EDN is a Ribonuclease

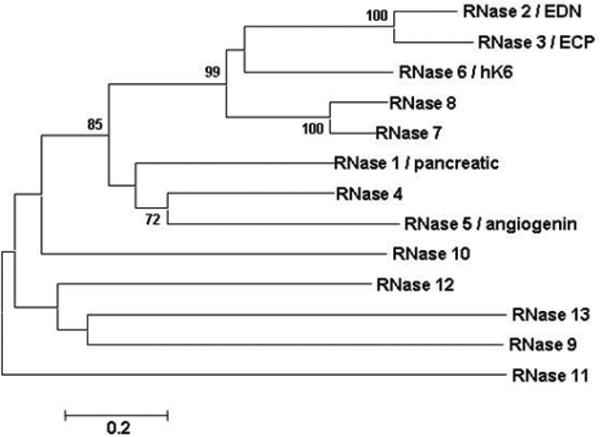

In 1986, Gleich and colleagues [12] reported the amino terminal sequence of EDN, which was not only similar to the amino terminal sequence of ECP, but proved to be unexpectedly similar to the amino terminal sequence of human pancreatic ribonuclease. Slifman and colleagues [13] subsequently showed that EDN was an enzymatically active ribonuclease, capable of generating acid soluble ribonucleotides from acid insoluble polymeric substrate with efficiency comparable to that of bovine pancreatic ribonuclease (RNase A). Molecular cloning of EDN [14, 15] confirmed the overall cDNA sequence homology between EDN and ECP at 89%, and clearly defined membership for both proteins in what was becoming recognized as an extensive RNase A superfamily (Fig. (2); reviewed in [16]). Completion of the human genome ultimately led to the recognition of 13 human RNase A ribonuclease genes. Eight of the RNase A ribonuclease genes encode enzymatically active proteins, and five encode divergent, inactive variants that have lost crucial structural or catalytic elements. EDN is also known as RNase 2, and, along with all active human RNase A ribonuclease genes, is located on q arm of chromosome 14 [17].

Fig. 2. Phylogenetic tree documenting relationships among the human RNase A ribonucleases.

Shown here is an unrooted neighbor-joining tree with distances determined with Poisson correction on complete amino acid sequences, as per algorithms of Mega 3.0 [46], with bootstrap values greater than 70 shown (5000 replications). EDN shares a basic cysteine structure and invariant catalytic histidines and lysines with other RNase A ribonucleases, but they are otherwise highly divergent from one another. Genbank accession numbers are listed in the original publication; reprinted with permission from [49].

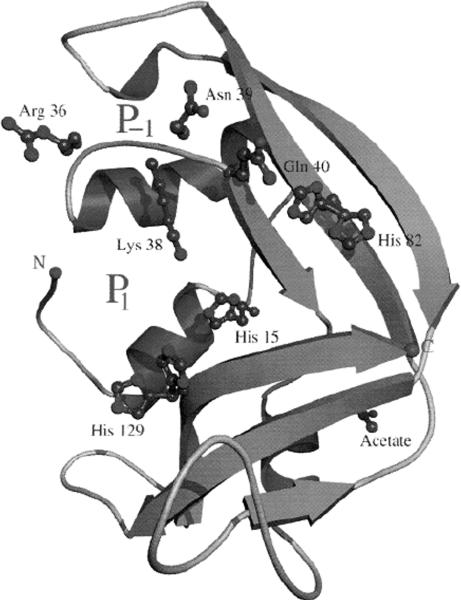

Of note, not only are EDN and EPX identical proteins, EDN is the same protein as human liver ribonuclease [18] and also the same as the protein earlier characterized as nonsecretory ribonuclease from human urine (RNase Us [19]). The crystal structure of EDN revealed substantial structural similarity to RNase A, the prototype of this gene family, but the peripheral substrate binding sites are not highly conserved [20, Fig. (3)].

Fig. 3. Ribbon diagram of recombinant EDN determined at 0.98 Å.

The relative positions of the catalytic His 15, His 129 and Lys 38 are as shown. Reprinted with permission from [20].

Rapid Evolution of EDN and its Rodent Orthologs

In our laboratory, we were initially quite frustrated at our inability to identify a mouse ortholog of EDN using standard Southern blot hybridization methodology. Upon further investigation, we were surprised to find that EDN could be detected by this method in primate genomic DNAs only [21]. Once complete coding sequences from a variety of primate species were isolated and sequenced, it became clear that EDN (and ECP) were evolving at an unusually rapid pace, and both genes were incorporating non-silent mutations at a rate of 1.9 and 2.0 × 10−9 substitutions / site / year, respectively. New World (South American) monkeys have only one gene, with some (e.g. lower isoelectric point) properties similar to EDN and some similar to ECP [22]. These results suggest that duplication creating the EDN-ECP gene pair occurred sometime after the divergence of the Old World from the New World monkeys.

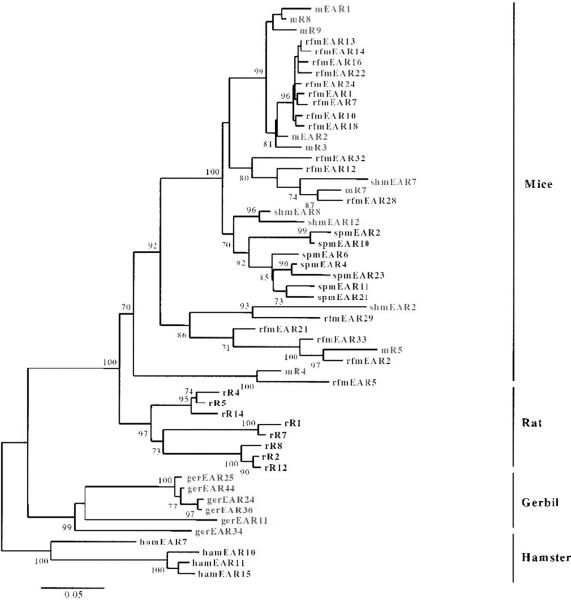

The first rodent orthologs of EDN (and ECP) were identified by Larsen and colleagues [23] by direct isolation of proteins from mouse eosinophils followed by amino terminal sequencing and ultimately, gene cloning. The mouse eosinophil-associated RNases are a highly divergent cluster of individual genes that have diverged by an unusual mechanism known as rapid birth-death followed by gene sorting [24], a mechanism that has been characterized for only a few other multi-gene families, typically those involved in generation of functional diversity (e.g. T cell receptor, major histocompatibility complex). Divergent eosinophil-associated RNases have also been identified in other rodent species, including hamsters, gerbils, guinea pigs and rats (Fig. (4); [24 - 26]).

Fig. 4. Phylogenetic tree documenting the relationships among the known functional eosinophil-associated ribonuclease genes in rodent species.

The eosinophil-associated ribonucleases are the orthologs of human EDN and ECP, and form extensive multi-gene species-limited clusters. Presented is a neighbor-joining tree prepared with MEGA 2.0 [47], with bootstrap values greater than 70 shown (1000 replications). Reprinted with permission from [24].

EDN is a Neurotoxin

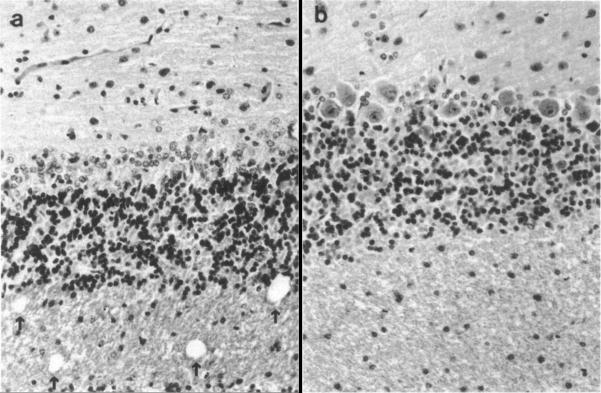

As noted earlier, EDN was named for its ability to reproduce the neurotoxic syndrome known as the Gordon phenomenon [3]. Both Durack and colleagues [5] and Fredens and colleagues [27] described the pathology observed in response to microgram quantities of EDN purified from eosinophils from patients with hypereosinophilic syndrome or from buffy coats from normal blood donors, which were injected intrathecally into male New Zealand White Rabbits or male and female Hartley strain albino guinea pigs, respectively. In both cases, the experimental animals developed ataxia and paralysis, with histopathologic lesions including loss of Purkinje cells and spongiform degeneration of cerebellar tissue. Fredens and colleagues noted that degeneration was most prominent in areas in contact with cerebrospinal fluid, and that disease could not be transmitted by re-inoculation of affected brain tissue (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Histopathologic abnormalities in rabbit cerebellum in response to EDN.

On the right, cerebellar tissue appears normal, with prominent Purkinje cells and intact white matter. On the left, in response to 50 μg purified EDN, Purkinje cells have disappeared, and vacuolization in the white matter is evident. Reprinted with permission from [5].

To this day, the mechanism of EDN's neurotoxicity remains mostly a mystery. For instance, it is not at all clear whether EDN exerts direct toxicity to Purkinje cells, or whether cell loss is the result of an indirect activation of another cell type, resulting in the release of a cytotoxic mediator. Sorrentino and colleagues [18] demonstrated that iodoacetate-inactivation of the ribonucleolytic activity of EDN eliminated its neurotoxic activity in the rabbit model. However, the neurotoxic activity is shared with the related RNase A ribonuclease ECP [27], and the very distantly related, and ribonucleolytically weak bullfrog ribonuclease, onconase [28], but it is not shared by the more closely related, and highly enyzmatically active human pancreatic RNase [28]. The question of ribonuclease-dependence might be addressed more directly if these experiments were repeated with recombinant proteins, where the ribonuclease activity could be eliminated in a more controlled fashion with point mutations in several known catalytically-critical amino acids.

EDN as an intracellular toxin

EDN alone has little to no cytotoxicity for somatic cells, other than the aforementioned neurotoxicity. However, when ligated to a single chain antibody (sFv) against the transferrin receptor, EDN is internalized as a ribonucleolytically-active cytoxin. Newton and colleagues [29] found that human leukemia cells that expressed the transferrin receptor were sensitive to nanomolar concentrations of EDNsFv. Similarly, EDN fusions with the cytotoxin, onconase resulted in enhanced enzymatic activity and augmented cytotoxicity [30], findings which may have implications for the development of improved anti-cancer chemotherapeutic agents.

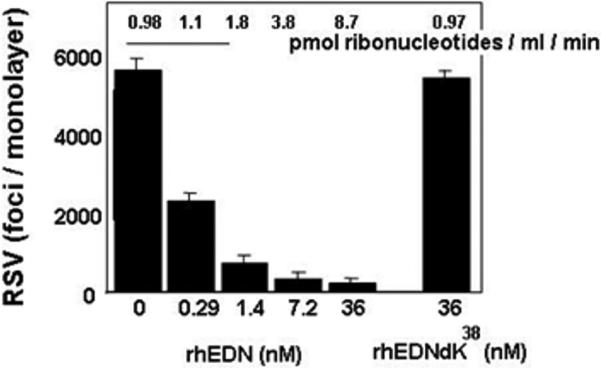

EDN reduces Virus Infectivity

Eosinophils are recruited in response to respiratory virus infection, most notably that caused by the pathogen, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV; [31,32]). Respiratory viruses (RSV, rhinovirus, adenovirus) are among the major factors known to exacerbate asthma, a disease where eosinophils are believed to play major roles in promoting pathogenesis [33]. Although eosinophils are generally perceived as having only negative contributions to make to inflammatory processes, our group provided the first evidence suggesting that eosinophils might also have some positive contributions in the form of antiviral host defense. Specifically, we have shown that eosinophils, and recombinant EDN, acting alone can reduce the infectivity of hRSV for target epithelial cells in culture in a manner directly dependent on ribonuclease activity [34] (Fig. 6). Furthermore, an exploration of complementary substitutions occurring during the evolution of EDN gene duplication at the divergence of the New World monkey lineages through the higher primates suggests that augmented ribonuclease activity and enhanced ribonuclease activity have developed coincidentally [35]. EDN also has activity against human immunodeficiency virus in vitro when tested in similar tissue-culture based assay systems [36 - 38]. Although the antiviral activity of the mouse eosinophil-associated ribonucleases has not been evaluated as clearly, eosinophils augment hRSV clearance in a mouse model, and can respond directly to hRSV by up-regulating mRNA encoding mouse eosinophil-associated RNases 1 and 2 [39]. Furthermore, infection of mice with the natural rodent pathogen, pneumonia virus of mice, results in prominent expression of mouse eosinophil-associated RNase 11 particularly in the absence of type I interferon-mediated signaling [40].

Fig. 6. Recombinant human EDN reduces the infectivity of the respiratory pathogen, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) for target epithelial cells in vitro.

The antiviral activity of recombinant human EDN (rhEDN) depends directly on its ribonuclease activity, as conversion of the active site lysine (K38) to the catalytically-inactive arginine (R) results in loss of both ribonuclease and antiviral activity. The full mechanism via which recombinant EDN reduces virus infectivity remains unclear. Reprinted with permission from [34].

EDN, mouse eosinophil-associated RNase 2, and Dendritic Cells (DCs)

As part of a larger exploration of the chemoattractant and activating properties of leukocyte granule proteins, Yang and colleagues [41] demonstrated that both recombinant EDN and recombinant mouse eosinophil-associated RNase 2 are selective chemoattractants for cultured dendritic cells. Bacterial-derived recombinant EDN displayed chemoattractant activity for immature DCs, and, although no specific receptor mediated-mechanism has been identified, the chemoattractant activity was sensitive to disruption with pertussis toxin, suggesting a G-protein coupled receptor-mediated mechanism. Likewise, recombinant mouse eosinophil-associated RNase 2 promoted DC chemoattraction in vitro and when injected into mouse skin in vivo. It is not clear which if any of these activities require enzymatic activity. (NB: Although this and other work reports on experiments performed in the presence of placental ribonuclease inhibitor (RI), RI is a large, complex protein that covers the entire EDN molecule, and is not a small molecule inhibitor of the active site; as such, addition of RI does not permit one to comment on the role of only enzymatic activity per se).

Taken one step further, Yang and colleagues [42] also demonstrated that bacterially-derived recombinant EDN promoted maturation and activation of dendritic cells. Among the mediators evaluated, in response to 1 μg/ml EDN, both CD34+ cell derived iDCs and monocyte-derived iDCs produce substantial quantities of interleukin (IL)-6, RANTES, TNF-α, MCP-2, MIP-1α, and IP-10.

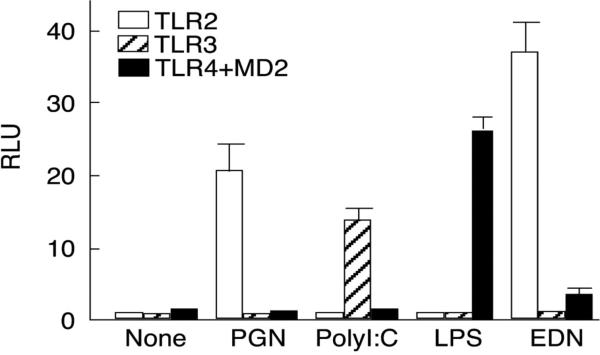

EDN as an endogenous ligand for TLR2

In conjunction with the aforementioned studies examining DC activation, Yang and colleagues [2] have presented evidence demonstrating that EDN can function as an endogenous ligand for toll-like receptor (TLR)2 (Fig. 7). As in previous studies, the involvement of enzymatic (ribonuclease) activity in TLR2 mediated signal transduction has not yet been evaluated; likewise unknown is whether or not this activity is shared with the parologous RNase A ribonuclease, ECP. However, on this basis of this and previous studies, the authors have classified EDN as among the alarmins, which are mediators that are capable of activating antigen presenting cells (such as dendritic cells), and are thus a link between innate and acquired immune responses [43]. While this most recent study focused on the TLR2 and DC activation and augmenting Th2-biased immune responses in vivo, the potential, more wide-ranging impact of this finding deserves some further consideration. Of particular interest, TLR2 is expressed on a wide variety of cells, including, relevant to the characterized functions of EDN, bronchial epithelial cells in the lung [44], and microglial cells in the brain [45]. As noted earlier, the mechanism of EDN's neurotoxicity remains obscure; might this involve aberrant activation of TLR2-mediated signaling pathways, ultimately resulting in release of mediators directly or indirectly toxic to cerebellar Purkinje cells? Likewise, might reduced virus infectivity involve TLR2-mediated alterations in bronchial epithelial target cells induced by EDN? These are questions that might be addressed experimentally in the not too distant future.

Fig. 7. EDN activates intracellular signaling pathways via TLR2.

HEK 293 cells were transfected with IgκB-luciferase and TLR-constructs, and stimulated for 24 hrs with characterized ligands or recombinant EDN (1 μg/ml). Reprinted with permission from [2].

Questions for the Future

Perhaps largest question relating to EDN and its role as an eosinophil secretory mediator, its involvement in respiratory virus infection, and its direct interactions with TLR2 and dendritic cells is the participation (or not) of its innate enzymatic activity. The unusual evolutionary constraints to which EDN is clearly responding, which have yielded a rapidly diverging lineage that somehow retains all structural and catalytic elements necessary for enzymatic activity, suggest that this activity must in some way be rather important to one or more physiologic functions, or else what would be the evolutionary impetus permitting these elements to be maintained? Similarly, if ribonuclease activity in general is important, might EDN have a specific endogenous substrate? Might EDN itself become derivatized as a ribonucleoprotein, and become active in that form? These are intriguing possibilities, and the answers to these questions remain elusive, as we do not yet have a complete picture of what activities are dependent on ribonuclease activity, and what the full biological context of these findings might mean.

Acknowledgements

Ongoing support for my laboratory work is from the NIAID Division of Intramural Research.

Abbreviations

- DC

dendritic cell

- ECP

eosinophil cationic protein

- EDN

eosinophil-derived neurotoxin

- EPO

eosinophil peroxidase

- EPX

eosinophil-protein X

- MBP

major basic protein

- RI

ribonuclease inhibitor

- RNase

ribonuclease

- RSV

respiratory syncytial virus

- sFv

singe chain antibody

- TLR2

toll-like receptor 2

References

- 1.Rothenberg ME, Hogan SP. Ann. Rev. Immunol. 2006;24:147–174. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang D, Chen Q, Su SB, Zhang P, Kurosaka K, Caspi RR, Michalek SM, Rosenberg HF, Zhang N, Oppenheim JJ. J. Exp. Med. 2008;205(1):75–90. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gordon MH. Br. Med. J. 1933;1:641–647. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.3771.641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Durack DT, Sumi SM, Klebanoff SJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1979;76(3):1443–1447. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.3.1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Durack DT, Ackerman SJ, Loegering DA, Gleich GJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., USA. 1981;78:5165–5169. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.8.5165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peterson CG, Venge P. Immunology. 1983;50(1):19–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Slifman NR, Venge P, Peterson CG, McKean DJ, Gleich GJ. J Immunol. 1989;143(7):2317–2322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamann KJ, Gleich GJ, Checkel JL, Loegering DA, McCall JW, Barker RL. J. Immunol. 1990;144:3166–3173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Molina HA, Kierszenbaum F, Hamann KJ, Gleich GJ. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1988;38:327–334. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1988.38.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamann KJ, Barker RL, Loegering DA, Gleich GJ. J. Parasitol. 1987;73:523–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ackerman SJ, Gleich GJ, Loegering DA, Richardson BA, Butterworth AE. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1985;34:735–745. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1985.34.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gleich GJ, Loegering DA, Bell MP, Checkel JL, Ackerman SJ, McKean DJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1986;83:3146–3150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.10.3146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slifman NR, Loegering DA, McKean DJ, Gleich GJ. J. Immunol. 1986;137:2913–2917. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenberg HF, Tenen DG, Ackerman SJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1989;86:4460–4464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.12.4460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamann KJ, Barker RL, Loegering DA, Pease LR, Gleich GJ. Gene. 1989;83:161–167. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90414-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenberg HF. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2008 In press. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cho S, Beintema JJ, Zhang J. Genomics. 2005;85(2):208–220. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sorrentino S, Glitz DG, Hamann KJ, Loegering DA, Checkel JL, Gleich GJ. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(21):14859–14865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beintema JJ, Hofsteenge J, Iwama M, Morita T, Ohgi K, Irie M, Sugiyama RH, Schieven GL, Dekker CA, Glitz DG. Biochemistry. 1988;27(12):4530–4538. doi: 10.1021/bi00412a046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swaminathan GJ, Holloway DE, Veluraja K, Acharya KR. Biochemistry. 2002;41(10):3341–3352. doi: 10.1021/bi015911f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenberg HF, Dyer KD, Tiffany HL, Gonzalez M. Nature Genet. 1995;10:219–223. doi: 10.1038/ng0695-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenberg HF, Dyer KD. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:21539–21544. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.37.21539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Larson KA, Olson EV, Madden BJ, Gleich GJ, Lee NA, Lee JJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:12370–12375. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang J, Dyer KD, Rosenberg HF. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:4701–4706. doi: 10.1073/pnas.080071397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singhania NA, Dyer KD, Zhang J, Deming MS, Bonville CA, Domachowske JB, Rosenberg HF. J Mol Evol. 1999;49(6):721–728. doi: 10.1007/pl00006594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakajima M, Hirakata M, Nittoh T, Ishihara K, Ohuchi K. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2001;125:241–249. doi: 10.1159/000053822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fredens K, Dahl R, Venge P. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1982;70(5):361–366. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(82)90025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Newton DL, Walbridge S, Mikulski SM, Ardelt W, Shogen K, Ackerman SJ, Rybak SM, Youle RJ. J Neurosci. 1994;14(2):538–544. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-02-00538.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Newton DL, Nicholls PJ, Rybak SM, Youle RJ. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(43):26739–26745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Newton DL, Xue Y, Boque L, Wlodawer A, Kung HF, Rybak SM. 1997. pp. 463–470. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Garofalo R, Kimpen JL, Welliver RC, Ogra PL. J Pediatr. 1992;120(1):28–32. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80592-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harrison AM, Bonville CA, Rosenberg HF, Domachowske JB. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159(6):1918–1924. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.6.9805083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jacobsen EA, Ochkur SI, Lee NA, Lee JJ. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2007;7(1):18–26. doi: 10.1007/s11882-007-0026-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Domachowske JB, Dyer KD, Bonville CA, Rosenberg HF. J. Infect. Dis. 1998;177:1458–1464. doi: 10.1086/515322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang J, Rosenberg HF. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci U S A. 2002;99(8):5486–5491. doi: 10.1073/pnas.072626199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee-Huang S, Huang PL, Sun Y, Huang PL, Kung HF, Blithe DL, Chen HC. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:2678–2681. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rugeles MT, Trubey CM, Bedoya VI, Pinto LA, Oppenheim JJ, Rybak SM, Shearer GM. AIDS. 2003;17:481–486. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200303070-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bedoya VI, Boasso A, Hardy AW, Rybak S, Shearer GM, Rugeles MT. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2006;22(9):897–907. doi: 10.1089/aid.2006.22.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Phipps S, Lam CE, Mahalingam S, Newhouse M, Ramirez R, Rosenberg HF, Foster PS, Matthaei KI. Blood. 2007;110:1578–1586. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-071340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garvey TL, Dyer KD, Ellis JA, Bonville CA, Foster B, Prussin C, Easton AJ, Domachowske JB, Rosenberg HF. J. Immunol. 2005;175:4735–4744. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.7.4735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang D, Rosenberg HF, Chen Q, Dyer KD, Kurosaka K, Oppenheim JJ. Blood. 2003;102:3396–3403. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang D, Chen Q, Rosenberg HF, Rybak SM, Newton DL, Wang ZY, Fu Q, Tchernev VT, Wang M, Schweitzer B, Kingsmore SF, Patel DD, Oppenheim JJ, Howard OM. J. Immunol. 2004;173:6134–6142. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.10.6134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oppenheim JJ, Tewary P, de la Rosa G, Yang D. Adv. Med. Biol. 2007;601:185–194. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-72005-0_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mayer AK, Muehmer M, Mages J, Gueinzius K, Hess C, Heeg K, Bals R, Lang R, Dalpke AH. J Immunol. 2007;178(5):3134–3142. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.3134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jack CS, Arbour N, Manusow J, Montgrain V, Blain M, McCrea E, Shapiro A, Antel JP. J Immunol. 2005;175(7):4320–4330. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.7.4320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kumar S, Tamura K, Nei M. Brief Bioinform. 2004;5:150–163. doi: 10.1093/bib/5.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kumar S, Tamura K, Nei M. MEGA, Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis. The Pennsylvania State University; University Park, PA: 1993. Version 1.02. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rosenberg HF, Phipps S, Foster PS. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119(6):1303–1310. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rosenberg HF, Dyer KD. Mol Divers. 2006;10(4):585–597. doi: 10.1007/s11030-006-9028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]