Abstract

Recently, Na+/K+-ATPase has been detected in the luminal membrane of the anterior midgut of larval yellow fever mosquitoes (Aedes aegypti) with immunohistochemical techniques. In this study, the possible involvement of this ATPase in strong alkalinization was investigated on the level of whole larvae, isolated and perfused midgut preparations and on the molecular level of the Na+/K+-ATPase protein. Ouabain (5 mM) did not inhibit the capability of intact larval mosquitoes to alkalinize their anterior midgut. Also in isolated and perfused midgut preparations the perfusion of the lumen with ouabain (5 mM) did not result in a significant change of the transepithelial voltage or the capacity of luminal alkalinization. Na+/K+-ATPase activity was completely abolished when KCl was substituted with choline chloride, suggesting that the enzyme cannot act as an ATP-driven Na+/H+-exchanger. Altogether the results of the present investigation indicate that apical Na+/K+-ATPase is not of direct importance for strong luminal alkalinization in the anterior midgut of larval yellow fever mosquitoes.

Strong luminal alkalinization of up to pH values of 12 has been observed in midgut regions of many larvae of endopterygote insects, including members of the orders Coleoptera, Diptera, Trichoptera and Lepidoptera (for references see Clark, '99). Two tissues have been studied especially intensively with regard to their mechanisms and capacities of alkalinization during the past 20 years: the midgut of the tobacco hornworm (Manduca sexta) and the anterior midgut of larval yellow fever mosquitoes (Aedes aegypti). For the lepidopteran larvae, a transport model has been established in which luminal V-type H+-pumps (V-ATPases) energize luminal, electrogenic K+/2H+-exchangers, resulting in active K+ secretion and strong luminal alkalinization (for a review see Wieczorek et al., '99). Unfortunately, this mechanism can so far not be tested with the isolated epithelium, because it loses the capacity for strong luminal alkalinization after isolation, whereas active K+ secretion continues in vitro at a high rate (Clark et al., '98). Strong luminal alkalinization in the anterior midgut of larval yellow fever mosquitoes appears to significantly differ from lepidopterans, including the methodological aspect that it can readily be observed with isolated and perfused midgut preparations (Onken et al., 2008). In larval A. aegypti, the V-ATPase is not localized in the luminal membrane of the anterior midgut, but instead in the basolateral membrane (Zhuang et al., '99). The epithelium of larval yellow fever mosquitoes generates a lumen negative transepithelial voltage (Clark et al., '99) instead of the lumen positive voltage observed in lepidopteran larvae under comparable conditions. In the midgut of lepidopteran larvae, carbonic anhydrase is very abundant (Ridgway and Moffett, '86) and could serve to rapidly supply acid/base transporters with their substrates. In contrast, carbonic anhydrase shows varying levels of activity/abundance in the anterior midgut of larvae of different mosquito species (Corena et al., 2004). The enzyme could not at all be found in the epithelium of the anterior midgut of larval A. aegypti (Corena et al., 2002), a species that nevertheless shows strong luminal alkalinization in this midgut region in vivo and in vitro (Dadd, '75; Onken et al., 2008). Indeed, inhibitors of carbonic anhydrase were shown to affect alkalinization in vivo or with in situ preparations of larval yellow fever mosquitoes (Boudko et al., 2001b; Corena et al., 2002). However, isolated and perfused anterior midgut preparations of A. aegypti readily alkalinized the lumen in the presence of such inhibitors (Onken et al., 2008) as would be expected from the absence of the enzyme in this midgut region.

Based on the results obtained with a wide array of experimental techniques using whole larvae, “semi-intact larvae” and isolated anterior midgut preparations it was established that basolateral V-ATPases drive strong luminal alkalinization in the anterior midgut of larval A. aegypti (Zhuang et al., '99; Boudko et al., 2001a; Onken et al., 2008). Addition of DIDS, an inhibitor of anion transporters, to the rearing medium eliminated the capability of generating an alkaline lumen in intact A. aegypti larvae, and it was proposed that exchangers in the luminal membrane are important for strong alkalinization (Boudko et al., 2001b). However, isolated and perfused anterior midgut preparations of larval yellow fever mosquitoes kept the capacity to alkalinize the lumen in the presence of luminal DIDS and even in the absence of luminal Cl− (Onken et al., 2008). Moreover, alkalinization was observed with isolated midgut preparations in the presence of luminal amiloride or in the presence of high luminal K+ concentrations, suggesting that K+/2H+ exchangers are also not essential for alkalinization in the anterior midgut of larval A. aegypti (Onken et al., 2008). Although the movement of acid equivalents via V-ATPases across the basolateral membrane seems to be well established (see above), the transporters responsible for the influx of acid and/or the efflux of base equivalents across the luminal membrane of larval yellow fever mosquitoes are still unknown.

In almost all epithelia the Na+/K+-ATPase is found in the basolateral membrane. A known exception is the retinal pigment epithelium (Okami et al., '90). Patrick et al. (2006) made a surprising observation when using antibodies to localize P-type Na+/K+-ATPase expression along the intestinal tract of larval A. aegypti. In the very anterior region of the anterior midgut this ATPase was expressed in the basolateral membrane as it is usually the case in epithelial tissues. However, in the major part of the anterior midgut the Na+/K+-ATPases was expressed in the luminal membrane. This finding, meanwhile confirmed in another study for Anopheles gambiae (Okech et al., 2008), is the basis for this study, which investigates the possible involvement of luminal Na+/K+-ATPases in strong luminal alkalinization. It is known since a long time that protons can substitute for Na+ and K+ in the reaction cycle of the Na+/K+-ATPase (Polvani and Blostein, '88). Could it be that this ATPase serves in the anterior midgut of A. aegypti as an ATP-driven Na+/H+ exchanger that mediates active proton absorption, resulting in the extremely high luminal pH?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mosquitoes

A. aegypti (Vero Beach strain) eggs were provided by Dr. Marc Klowden (University of Idaho, Moscow, USA) from a continuously maintained colony. Eggs were hatched and larvae were maintained in a 1:1 mixture of tap water and deionized water at 27°C at a 16:8 hr L:D photo-period. The water was replaced each morning, and the larvae were fed with ground Tetramin flakes (Tetrawerke, Melle, Germany). Fed fourth-instar larvae were used for all experiments.

Assays with whole living larvae

In order to evaluate the importance of Na+/K+-ATPase in the luminal membrane for strong alkalinization in larval A. aegypti fourth-instar larvae were exposed to water containing m-cresol purple (0.04 %) with or without ouabain (5 mmol L−1), a specific inhibitor of Na+/K+-ATPase (Skou, '65). After 40 min the larvae were transferred into distilled water and the coloration of the midgut was observed and recorded under a stereo microscope. Afterwards the larvae were returned into the water with the dye and with or without ouabain, and the procedure was repeated after 60, 100 and 130 min.

Assays with isolated and perfused anterior midguts

Manufacture of perfusion pipettes, the preparation, mounting and perfusion of anterior midgut preparations as well as the measurement of the transepithelial voltage (Vte) and the determination of alkalinization was conducted as outlined in detail before (Onken et al., 2004a,b; Onken et al., 2008) and will be described only briefly here.

After killing the larvae, the alimentary canal was isolated and transferred into the bath of a perfusion chamber with a volume of 100 μL (perfused by gravity flow with oxygenated mosquito saline at a rate of 15–30 mL hr−1). Caeca, hindgut and Malpighian tubules were cut off and the posterior midgut was slipped onto an L-shaped perfusion pipette held by a micromanipulator (Brinkmann, Westbury, NY) until the tip of the pipette recorded the typical, lumen negative Vte. The preparations were tied in place with a human hair. In order to keep the tissue in the focal plane of the binocular microscope, the open anterior end of the preparation was slipped onto a glass rod manufactured from a capillary pipette (20 μL; VWR, West Chester, PA) and held by a second micromanipulator. The perfusion pipette contained a polyethylene tubing (Intramedic PE 10; VWR) and was closed with a syringe needle (23 gauge). The syringe needle and the tubing were connected to two push–pull multi-speed syringe pumps (model Aladdin; World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL), allowing fast changes of the luminal perfusion (rate 30 μL hr−1) between NaCl (100 mmol L−1) solutions with and without ouabain (5 mmol L−1). The transepithelial voltage (Vte) was measured exactly as described before (Onken et al., 2004a,b). Only those preparations that showed the typical marked increase of Vte after application of hemolymph-side serotonin (0.2 μmol L−1; cf. Clark et al., '99) were used for data collection. Alkalinization of the luminal perfusate was monitored after perfusion stop through the color changes of the pH indicator mcresol purple. For further details about the documentation of luminal alkalinization see Onken et al. (2008).

Midgut homogenization and assay of Na+/K+-ATPase activity

Single alimentary canals of larval A. aegypti were isolated and the caeca, hindgut and Malpighian tubules were cut off. Each midgut (8.8 ± 1.9 μg of protein, N = 6, ±standard error of the mean (S.E.M.)) was homogenized in an ice-cold glass homogenizer in 50 μL of ice cold homogenization buffer, containing HEPES (10 mmol L−1), Na2EDTA (5 mmol L−1), sucrose (250 mmol L−1) and C12E10 (0.05%) adjusted to a pH of 7.5 with TRIS. Homogenization was achieved with 15 up and down movements of the pestle each accompanied by a 180° turn. ATPase activities were measured according to Onishi et al. ('76) as liberated inorganic phosphate in the homogenate. Measurement of Na+/K+-ATPase activity was conducted similar to Kosiol et al. ('88), incubating in each assay 9 μL of the homogenate for 30 min with 21 μL of a reaction buffer containing NaCl (100 mmol L−1), KCl (20 mmol L−1), MgCl2 (4 mmol L−1), HEPES (50 mmol L−1), TRIS (9 mmol L−1) and Na2ATP (3 mmol L−1) adjusted to a pH of 7.5 with TRIS. Na+/K+-ATPase activity was defined as the difference between the activities obtained with and without 5 mmol L−1 ouabain. Assays were conducted in the presence and absence of K+ (substituting KCl with choline chloride). The protein contents of the homogenates were measured according to the method of Bradford ('76), modified according to Sedmark and Grossberg ('77), with bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Solutions and chemicals

The basic saline used to bath the isolated anterior midgut preparations was based on larval Aedes hemolymph composition (Edwards, '82a,b) and consisted of (in mmol L−1): NaCl, 42.5; KCl, 3.0; MgCl2, 0.6; CaCl2, 5.0; NaHCO3, 5.0; succinic acid, 5.0; malic acid, 5.0; l-proline, 5.0; l-glutamine, 9.1; l-histidine, 8.7; l-arginine, 3.3; dextrose, 10.0; Hepes, 25. The pH was adjusted to 7.0 with NaOH.

All chemical reagents to prepare the mosquito saline, the luminal perfusion salines and the reaction media for ATPase and protein assays were of analytical grade and purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO), Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA) or Mallinckrodt (Hazelwood, MO).

Statistics

All data are presented as means±S.E.M.. Differences between the groups were tested, using Student's t-test. Significance was assumed at P<0.05.

RESULTS

Alkalinization in living larvae

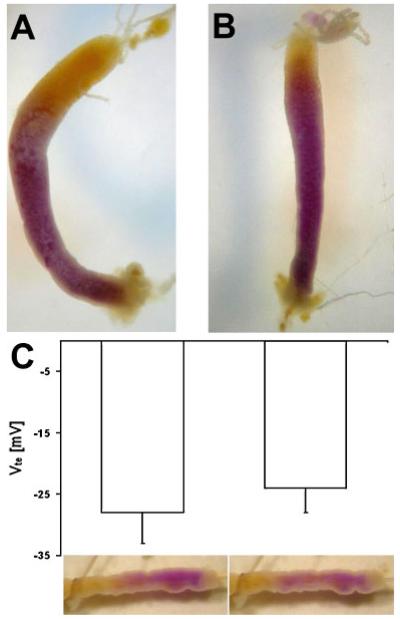

Twenty A. aegypti fourth-instar larvae were incubated in the presence of ouabain (5 mmol L−1) and 20 larvae were incubated without the drug to serve as a control group. After 40 min all the larvae had developed the pink coloration of mcresol purple in their anterior midguts, indicating strong alkalinization in this region of the intestine. The same observation was made after 60, 100 and 130 min of incubation time, indicating that the inhibitor of Na+/K+-ATPase did not affect alkalinization in the anterior midgut when applied to the medium (see Fig. 1A and B).

Fig. 1.

(A) Midgut isolated from a fourth-instar larval A. aegypti after 60 min incubation in water containing 0.04% mcresol purple. (B) Midgut isolated from a fourth-instar larval A. aegypti after 60 min incubation in water containing 0.04% m-cresol purple and 5 mM ouabain. (C) Transepithelial voltage (Vte) of isolated anterior midgut preparations (N = 7, −S.E.M.) bathed in oxygenated mosquito saline with 0.2 μM serotonin and perfused with NaCl (100 mM) containing 0.04% m-cresol purple with (right column) and without (left column) luminal ouabain (5 mM). The photos below the graph show one example preparation after 5 min of perfusion stop.

Alkalinization in isolated anterior midguts

After perfusing seven isolated anterior midgut preparations with NaCl (100 mmol L−1) and mcresol purple (0.04%) for approximately 30 minutes in a bath of oxygenated mosquito saline containing 0.2 μmol L−1 serotonin we observed an average, lumen negative transepithelial voltage of −28±5 mV (N = 7, ±S.E.M.). Perfusion stop resulted in all cases in a color change of the lumen from yellow to purple, indicating the capacity for strong luminal alkalinization. After switching to a luminal perfusion medium containing ouabain (5 mmol L−1) Vte changed to less negative values in four cases, whereas in three cases the transepithelial voltage increased to more negative values as under control conditions. The average Vte after 30–60 min of incubation with ouabain was −24±4 mV (N = 7, ±S.E.M.) and did not significantly differ from the control conditions (P<0.05). In all seven cases a perfusion stop in the presence of ouabain resulted in a similar color change from yellow to purple as had been observed before application of the drug to the lumen of the anterior midguts (see Fig. 1C).

Na+/K+-ATPase activity in presence and absence of potassium

In order to test whether the Na+/K+-ATPase in the midgut of larval A. aegypti could act as an ATP-driven Na+/H+-exchanger, we measured Na+/K+-ATPase activity in the presence and absence of potassium. In the presence of potassium the Na+/K+-ATPase activity amounted to 86.2±2.5 nmol Pih−1 midgut−1 (N = 3, ±S.E.M.) and the specific Na+/K+-ATPase activity was 10.6±2.2 μmol Pih−1 mg−1 (N = 3, ±S.E.M.). When KCl was substituted with choline chloride in the assay the specific Na+/K+-ATPase activity decreased to 0.1±0.1 μmol Pih−1 mg−1 (N = 3, ±S.E.M.). The results are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Ouabain-sensitive ATPase activity in midgut homogenates of fourth-instar larval A. aegypti

| Activity per midgut (nmol Pih−1 midgut−1) |

Specific activity (μmol Pih−1 mg−1) |

N | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Na+ and K+ | 86.2±2.5 | 10.6±2.2 | 3 |

| Na+ and choline | 1.0±1.0 | 0.1±0.1 | 3 |

DISCUSSION

As outlined in the introduction the luminal transport mechanisms for acid/base equivalents in the alkalinizing anterior midgut of larval yellow fever mosquitoes are so far unknown. Involvement of secretion seems evident, but pharmacological analyses with different preparations returned contradictory results about base secretion via exchangers and/or Na+/2-3 cotransporters (Boudko et al., 2001b; Onken et al., 2004, 2008). secretion alone can anyway not explain pH values above 8.5. Combination with H+ absorption, however, could turn the secretion into secretion, and readily explain the extremely high pH values observed in the anterior midgut of larval mosquitoes. When Patrick et al. (2006) discovered that Na+/K+-ATPase is expressed in the luminal membrane of the major portion of the anterior midgut, it was near at hand to assume that this ATPase is more or less directly involved in alkalinization. Because it is known that protons can substitute for Na+ and K+ in the reaction cycle of the Na+/K+-ATPase (Polvani and Blostein, '88), we hypothesized that the ATPase could serve as an ATP-driven Na+/H+-exchanger. Such an active H+ absorption could then serve to drive the luminal pH from 8.5 to values above 10. In the present investigation we studied this hypothesis on three levels: whole larvae, isolated midguts and the ATPase itself.

Larval mosquitoes drink the rearing medium (cf. Clements, '92). Therefore, and because larval mosquitoes are transparent, it is possible to determine the pH value of their intestinal system in vivo by adding pH indicator to the water (cf. Dadd, '75). If the animals ingest the dye, also other substances dissolved in the rearing medium like inhibitors of transporters should enter their digestive system. However, addition of ouabain, a specific inhibitor of Na+/K+-ATPase (Skou, '65), to the rearing medium did not prevent luminal alkalinization in the anterior midgut (see Fig. 1). Indeed, results obtained with whole larvae in vivo in this way must be ambiguous; however, the result of the experiment turns out. In this kind of experiment it remains unknown in which section of the digestive tract the drugs are absorbed or modified by digestive processes. Absorption of the drug could result in its activity in unpredictable locations, and breakdown or partial modification may render it completely ineffective. In this study it could well be that ouabain was broken down already before it reached the anterior midgut. Therefore, we used the drug also with isolated and perfused midgut preparations.

In a previous investigation (Onken et al., 2008) it was shown that isolated and perfused anterior midgut preparations of larval yellow fever mosquitoes alkalinize the lumen within minutes to pH values above 10 in the presence of hemolymph-side serotonin. In these experiments the luminal perfusate was low-buffer mosquito saline, containing glucose, amino acids and metabolites (succinate, malate). In this study we used NaCl (100 mmol L−1) as luminal perfusion medium under control conditions. Alkalinization was readily observed (see Fig. 1), showing that luminal alkalinization does not depend on the absorption of amino acids or other organic acids. However, the addition of ouabain to the luminal perfusion medium did not significantly affect the recorded transepithelial voltage, and luminal alkalinization was also unaffected by the drug (see Fig. 1).

In isolated Malpighian tubules of some insects, including adult mosquitoes, ouabain has no or only little effects on fluid secretion (Williams and Beyenbach, '84; Hegarty et al., '91; Dow et al., '94; Leyssens et al., '94; Weng et al., 2003), although the Na+/K+-ATPase is present in the basolateral membrane. Torrie et al. (2004) addressed this so-called “ouabain paradox” in Drosophila melanogaster. In this study, the rapid tubular secretion of ouabain was shown to protect the basolateral ATPase from ouabain applied to the basolateral surface. Basolateral uptake of ouabain is carried out by an organic anion-transporting polypeptide (OATP). Addition of taurocholate, another substrate of OATP, reversed the protective effect, revealing the involvement of the basolateral Na+/K+-ATPase in fluid secretion by Malpighian tubules. Could such a process have affected the results of these studies? We regard this as unlikely for two reasons. First, it is necessary to suppose that ouabain is avidly absorbed across the anterior midgut. Although specific data for ouabain are not available, generally the midgut and Malpighian tubules act in concert, rather than in opposition, in management of environmental toxins (cf Nijhout, '75; Bijelic and O'Donnell, 2005), so that active secretion of ouabain by the midgut would seem more likely than absorption. Secondly, in the Malpighian tubule studies alluded to above (including that of Torrie et al., 2004) the tissues were bathed in a small, unreplenished drop of saline. This setup would allow the OATP transporters to rapidly deplete the ouabain in the droplet, as well as creating microenvironments of low ouabain concentration close to the ATPases located in the intensively folded basolateral membrane. In contrast, in our in vitro study the midgut lumen was perfused with a high ouabain concentration and at a high rate (exchanging the entire volume of the preparation three–nine times per minute). Furthermore, the apical membrane of anterior midgut cells lacks intensive infoldings or a brush border (Zhuang et al., '99) that could facilitate formation of ouabain-free microenvironments. In a previous study of the midgut of larval mosquitoes (Onken et al., 2004a,b) hemolymph-side ouabain significantly reduced the transepithelial voltage by about 15%. Patrick et al. (2006) showed that basolateral Na+/K+-ATPase is only present in the very first segment of the anterior midgut. Together with the dominant role of basolateral V-ATPases in this tissue (see introduction) this can explain the relatively small influence of the hemolymph-side ouabain on Vte. In sum, the above observations seem to make an involvement of OATPs, or an analogous process, in the noneffectiveness of ouabain very unlikely. Nevertheless, future experiments should consider the possible presence and roles of OATPs in the midgut of larval mosquitoes.

In order to study whether Na+/K+-ATPase in the midgut of larval A. aegypti can accept H+ as a substitute for K+, we measured ouabain-sensitive ATPase activity in homogenates of single, isolated midguts. The activity of the Na+/K+-ATPase per midgut was about ten times higher than reported previously (Bernick et al., 2004), suggesting that the new approach with homogenates of single midguts is a successful estimation of the true ATPase activity. On the other hand, the specific activity observed was about ten times lower than reported for the midgut of adult mosquitoes (MacVicker et al., '93), which may suggest that after transformation from larva to adult this ATPase plays a larger role in the midgut. In any case, when we substituted KCl with choline chloride in the ATPase assay the activities fell to values very close to zero, indicating that the Na+/K+-ATPase in the midgut of larval A. aegypti cannot serve as an effective ATP-driven Na+/H+ exchanger.

Altogether the results of our study do not support our hypothesis that Na+/K+-ATPase in the midgut of larval A. aegypti contributes to luminal alkalinization by actively absorbing H+ and turning secretion into secretion. The physiological importance of the luminal expression of Na+/K+-ATPase in the midgut of larval yellow fever mosquitoes seems therefore not to be related to its alkalinizing role and remains to be elucidated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Financial support for this work was provided by the National Institute of Health (1R01AI063463-01A2). We thank Marc Klowden for supplying Aedes aegypti eggs and Leonard Kirschner for helpful discussions and suggestions.

Grant sponsor: National Institute of Health; Grant number: 1R01AI063463-01A2.

LITERATURE CITED

- Bernick EP, Onken H, Kirschner LB, Moffett DF. ATPase activities in Aedes aegypti midgut; SICB 2004 Annual Meeting; 2004. p. 345p. Abstracts, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bijelic G, O'Donnell MJ. Diuretic factors and second messengers stimulate secretion of the organic cation TEA by the Malpighian tubules of Drosophila melanogaster. J Insect Physiol. 2005;51:267–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudko DY, Moroz LL, Harvey WR, Linser PJ. Alkalinization by chloride/bicarbonate pathway in larval mosquito midgut. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2001a;98:15354–15359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261253998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudko DY, Moroz LL, Linser PJ, Trimarchi JR, Smith PJS, Harvey WR. In situ analysis of pH gradients in mosquito larvae using non-invasive, self-referencing, pH-sensitive microelectrodes. J Exp Biol. 2001b;204:691–699. doi: 10.1242/jeb.204.4.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein–dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark TM. Evolution and adaptive significance of larval midgut alkalinization in the insect superorder Mecopterida. J Chem Ecol. 1999;25:1945–1960. [Google Scholar]

- Clark TM, Koch A, Moffett DF. Alkalinization by Manduca sexta anterior midgut in vitro: requirements and characteristics. Comp Biochem Physiol A. 1998;121:181–187. [Google Scholar]

- Clark TM, Koch A, Moffett DF. The anterior and posterior ‘stomach’ regions of larval Aedes aegypti midgut: regional specialization of ion transport and stimulation by 5-hydroxytryptamine. J Exp Biol. 1999;202:247–252. doi: 10.1242/jeb.202.3.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements AN. The biology of mosquitoes. Chapman & Hall; London: 1992. p. 509p. [Google Scholar]

- Corena MDP, Seron TJ, Lehman HK, Ochrietor JD, Kohn A, Tu C, Linser PJ. Carbonic anhydrase in the midgut of larval Aedes aegypti: cloning, localization and inhibition. J Exp Biol. 2002;205:591–602. doi: 10.1242/jeb.205.5.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corena MDP, Fiedler MM, VanEkeris L, Tu C, Silverman DN, Linser PJ. Alkalization of larval mosquito midgut and the role of carbonic anhydrase in different species of mosquitoes. Comp Biochem Physiol C. 2004;137:207–225. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadd RH. Alkalinity within the midgut of mosquito larvae with alkaline-active digestive enzymes. J Insect Physiol. 1975;21:1847–1853. doi: 10.1016/0022-1910(75)90252-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dow JAT, Maddrell SHP, Görtz A, Skaer NJV, Brogan S, Kaiser K. The malpighian tubule of Drosophila melanogaster: a novel phenotype for studies of fluid secretion and its control. J Exp Biol. 1994;197:421–428. doi: 10.1242/jeb.197.1.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards HA. Ion concentration and activity in the haemolymph of Aedes aegypti larvae. J Exp Biol. 1982a;101:143–151. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards HA. Free amino acids as regulators of osmotic pressure in aquatic insect larvae. J Exp Biol. 1982b;101:153–160. [Google Scholar]

- Hegarty JL, Zhang B, Pannabecker TL, Petzel DH, Baustian MD, Beyenbach KW. Dibutyryl cAMP activates bumetanide-sensitive electrolyte transport in malpighian tubules. Am J Physiol. 1991;261:C521–C529. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1991.261.3.C521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosiol B, Bigalke T, Graszynski K. Purification and characterization of gill (Na+, K+)-ATPase in the freshwater crayfish Orconectes limosus Rafinesque. Comp Biochem Physiol. 1988;89:171–177. [Google Scholar]

- Leyssens A, Dijkstra S, Van Kerkhove E, Steels P. Mechanisms of K+ uptake across the basal membrane of malpighian tubules of Formica polyctena: the effects of ions and inhibitors. J Exp Biol. 1994;195:123–145. doi: 10.1242/jeb.195.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacVicker JAK, Billingsley PF, Djamgoz MBA. ATPase activity in the midgut of the mosquito Anopheles stephensi: biochemical characterization of ouabain-sensitive and ouabain-insensitive activities. J Exp Biol. 1993;174:167–183. doi: 10.1242/jeb.174.1.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijhout HF. Excretory role of the midgut in larvae of the tobacco hornworm Manduca sexta (L.) J Exp Biol. 1975;62:221–230. doi: 10.1242/jeb.62.1.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okami T, Yamamoto A, Omori K, Takada T, Uyama M, Tashiro Y. Immunocytochemical localization of Na+, K+-ATPase in rat retinal pigment epithelial cells. J Histochem Cytochem. 1990;38:1267–1275. doi: 10.1177/38.9.2167328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okech BA, Boudko DY, Linser PJ, Harvey WR. Cationic pathway of pH regulation in larvae of Anopheles gambiae. J Exp Biol. 2008;211:957–968. doi: 10.1242/jeb.012021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onishi T, Gall RS, Mayer ML. An improved assay of inorganic phosphate in the presence of extralabile phosphate compounds: application to the ATPase assay in the presence of phosphocreatine. Anal Biochem. 1976;69:261–267. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(75)90585-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onken H, Moffett SB, Moffett DF. The transepithelial voltage of the isolated anterior stomach of mosquito larvae (Aedes aegypti): pharmacological characterization of the serotonin-stimulated cells. J Exp Biol. 2004a;207:1779–1787. doi: 10.1242/jeb.00964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onken H, Moffett SB, Moffett DF. The anterior stomach of larval mosquitoes (Aedes aegypti): effects of neuropeptides on transepithelial ion transport and muscular motility. J Exp Biol. 2004b;207:3731–3739. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onken H, Moffett SB, Moffett DF. Alkalinization in the isolated and perfused anterior stomach of larval Aedes aegypti. J Insect Sci. 2008;8:43. doi: 10.1673/031.008.4601. available online: insectscience.org/8.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Patrick ML, Aimanova K, Sanders HR, Gill SS. P-type Na+/K+-ATPase and V-type H+-ATPase expression patterns in the osmoregulatory organs of larval and adult mosquito Aedes aegypti. J Exp Biol. 2006;209:4638–4651. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polvani P, Blostein R. Protons as substitutes for sodium and potassium in the sodium pump reaction. J Biol Chem. 1988;260:16757–16763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridgway RL, Moffett DF. Regional differences in the histochemical localization of carbonic anhydrase in the midgut of tobacco hornworm (Manduca sexta) J Exp Zool. 1986;237:407–412. [Google Scholar]

- Sedmark JJ, Grossberg SE. A rapid, sensitive and versatile assay for protein using Coomassie Brilliant Blue G250. Anal Biochem. 1977;79:544–552. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(77)90428-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skou JC. Enzymatic basis for active transport of Na+ and K+ across cell membrane. Physiol Rev. 1965;45:596–617. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1965.45.3.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrie LS, Radford JC, Southall TD, Kean L, Dinsmore AJ, Davies SA, Dow JAT. Resolution of the insect ouabain paradox. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2004;101:13689–13693. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403087101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng X-H, Huss M, Wieczorek H, Beyenbach KW. The V-type H+-ATPase in malpighian tubules of Aedes aegypti: localization and activity. J Exp Biol. 2003;206:2211–2219. doi: 10.1242/jeb.00385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieczorek H, Grüber G, Harvey WR, Huss M, Merzendorfer H. The plasma membrane H+ V-ATPase from tobacco hornworm midgut. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1999;31:67–74. doi: 10.1023/a:1005448614450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JC, Beyenbach W. Differential effects of secretagogues on the electrophysiology of malpighian tubules of the yellow-fever mosquito. J Comp Physiol. 1984;154:301–309. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang Z, Linser PJ, Harvey WR. Antibody to H+ V-ATPase subunit E colocalizes with portasomes in alkaline larval midgut of a freshwater mosquito (Aedes aegypti L.) J Exp Biol. 1999;202:2449–2460. doi: 10.1242/jeb.202.18.2449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]