Abstract

Objective

Little is known about depression during pregnancy in women with high maternal or fetal risk, as this population is often excluded from research samples. The aim of this study was to evaluate depressive symptoms and known risk factors for depression in a group of women hospitalized with severe obstetric risk.

Method

In the antenatal unit, 129 inpatients completed the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS), and the Maternal Antenatal Attachment Scale (MAAS) from October 2005 through December 2006. A subset of women were administered the Mood Disorder module of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID) based upon a score of ≥ 11 on the EPDS. Obstetric complications were classified according to the Hobel Risk Assessment for Prematurity.

Results

Fifty-seven of the 129 women (44.2%) scored 11 or greater on the EPDS, and at least 25/129 (19%) met the DSM-IV criteria for Major Depressive Disorder (MDD). Mothers reporting high attachment to the fetus on the MAAS reported lower severity of depressive symptoms (rho = −0.33, p < 0.001); those reporting interpersonal relationship dissatisfaction on the DAS endorsed higher depressive severity (rho = −0.21, p = 0.02). Severity of obstetric risk was unrelated to depression but, one complication, incompetent cervix, was positively associated with level of depressive symptomatology.

Conclusion

Findings indicate a higher prevalence rate of MDD in women with severe obstetric risk than that reported in low-risk pregnancy samples, suggesting the need for routine depression screening to identify those who need treatment. Fewer depressive symptoms were reported by mothers reporting strong maternal fetal attachment andgreater relationship satisfaction.

Keywords: Prenatal Depression, Antenatal Depression, Perinatal Depression, Pregnancy, Obstetric Risk, Obstetric Complications

Introduction

Over one million pregnant women a year are identified as being at high-risk for obstetric complications, approximately 700,000 of which are treated with bed rest.1 As described by Penticuff, a pregnancy may be defined “high risk” on the basis of an increased probability of fetal anomaly, compromises to maternal or fetal health, or significant risk for maternal or fetal demise.2 Although maternal mortality in the developed countries has steadily decreased, complications threatening the life of the newborn have increased in the U.S.3 In the nursing literature, a few studies focusing on hospitalized women have identified higher levels of symptoms of anxiety and depression,4 lower self-image,5 less positive expectations for their experience of childbirth,6 and less optimal family functioning than have been found in studies of non-hospitalized women.7 Other psychosocial aspects such as partner support, relationship satisfaction, and maternal-fetal attachment have been viewed as potentially compromised in women experiencing “uncertain motherhood,”2, 8, 9 but this has not been corroborated in the limited research.10–12 One research team found dysphoria (a composite of anxiety, depression, and hostility) highest upon hospital admission and significantly greater for those with the highest Hobel Risk Assessment for Prematurity scores.4 Even though screening for depression in such women has been encouraged,13 few well-designed studies have been conducted to evaluate the rates of major depressive disorder in this high risk population. Those few that have put forward estimates have primarily assessed symptoms of psychopathology and have not focused on clarifying the true rates of diagnosable major depressive disorder.

However, considerable research has been conducted with healthy pregnant women, and findings all point to the serious consequences of depression during the perinatal period, including adverse obstetric and neonatal outcomes.14, 15 Further, several teams have investigated predictive factors of postpartum depression, finding connections with a previous episode of major depression (particularly during pregnancy), poor relationship quality, low attachment to the fetus, and maternal or fetal complications during pregnancy.16, 17 Although obstetric risk has been identified in a number of retrospective studies as a moderate predictor of postpartum depression, most prospective investigators have excluded women with high risk from perinatal research. Therefore, to date, no published prevalence or incidence rates for Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) as diagnosed by a clinical interview (instead of self-report screening score measures) have been available for such women. For women with uncomplicated pregnancy, the best estimate of point prevalence for MDD at any time during pregnancy is 12.7%, with as many as 18.4% reporting major or minor depression.18

In light of this, an investigation was conducted in a population of women hospitalized for high obstetric risk for the purpose of:

Examining the prevalence of MDD and sub-syndromal levels of symptomatology, and

Investigating potential associations of depression with relationship satisfaction, maternal fetal attachment, and obstetric risk.

Methods

Participants

The cross-sectional sample of this descriptive study consisted of 129 women who were between 7 and 38 weeks pregnant (m = 28.2, sd = 5.2) participating in a larger protocol. After approval by the Institutional Review Board of Baylor University Medical Center, all women admitted to Baylor University Medical Center Antepartum Unit in Dallas, Texas for severe obstetric complications (as defined previously) were invited to participate in this research. Data for the first phase of the larger study were collected from October 2005 to December 2006.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

All English- and Spanish-speaking women who were hospitalized in the antepartum unit of Baylor University Medical Center for obstetric complications were study eligible. Hospitalization was based upon the significant possibility of negative health outcome for fetus and/or mother (Table 3 reports the specific complications represented by the sample). Patients who were cognitively impaired, actively suicidal, homicidal, or psychotic were excluded. Women who were unable to verbally communicate in either English or Spanish were excluded due to the lack of validated instruments in other languages and limitations of study personnel. Patients who were not expected to remain hospitalized for longer than 72 hours were also excluded, as there would have been insufficient time for scheduling the interview and administering measures. In addition, two women were excluded due to the severity of medical condition (end-stage liver failure and end-stage renal failure), and another was excluded because she was a surrogate mother and would not have been able to complete the subsequent phases of the larger protocol.

Table 3.

Obstetric Complications Represented

| Frequency | Percent | Frequency EPDS ≥ 11 | Percent Of Group | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | 8 | 6.2 | 5 | 62.5 |

| Incompetent Cervix* | 35 | 27.1 | 21 | 60.0 |

| Premature Rupture of Membranes | 30 | 23.3 | 12 | 40.0 |

| Placenta Previa | 4 | 3.1 | 1 | 25.0 |

| Toxemia | 12 | 9.3 | 6 | 50.0 |

| Diabetes | 4 | 3.1 | 3 | 75.0 |

| Multiple Pregnancy | 17 | 13.2 | 7 | 41.2 |

| Preterm Labor | 56 | 43.4 | 25 | 44.6 |

| Total percent exceeds 100 due to some participants with multiple complications. | ||||

Significant association with Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (p <.05).

Measures

The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) was developed specifically for the screening and assessment of postpartum depression,19 but has become widely used during the entire perinatal period.20 It inquires about the common neurovegetative symptoms of depression, excluding somatic symptoms such as fatigue and changes in appetite that occur naturally in pregnancy and would be less likely to discriminate depressed women from non-depressed women. The split-half reliability of the EPDS is 0.88 and the standardized Cronbach’s α coefficient was 0.87.21 Total scores on this 10-item, multiple-choice scale range from 0 to 30, with higher scores reflective of greater symptom severity. Recommended threshold scores for indicated depression range from 9 to 13;20 as recommended for high-risk women,13 11 was selected as the cut-off score and dictated the administration of the SCID Mood Disorder module to review symptoms and establish or rule out the diagnosis of MDD as defined in the DSM-IV-TR.

The Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS) is a self-report inventory that assesses relationship satisfaction or adjustment and is one of the most commonly used measures for this purpose.22, 23 Thirty-two items evaluate several aspects of a relationship, including finances, affection, and sexuality. Factor analysis identifies four measured aspects of the relationship: Dyadic Satisfaction, Dyadic Cohesion, Dyadic Consensus, and Affectional Expression. The theoretical range of total scores possible is 0–151, and those that fall below 100 suggest relationship distress.24 Internal consistency of the DAS is reported as Cronbach’s α = 0.96 (in non-pregnant couples). Known-groups validity has been indicated by the ability of the DAS to discriminate between married and divorced couples on each item; concurrent validity has been demonstrated with a number of other relationship scales.22, 23 The instrument has been utilized with pregnant women and was able to discriminate between those who became depressed postpartum and those who did not.25, 26 Participants were asked to complete the DAS if they were married or in a committed relationship.

The Maternal Antenatal Attachment Scale (MAAS) is a self-report questionnaire designed to capture the developing attachment of mother to fetus.27, 28 Nineteen items report on two dimensions: “Quality” assesses positive emotions and thoughts regarding closeness, tenderness, the desire to know and see the baby, as well as vivid internal representations of the fetus, and “Intensity” measures the mother’s preoccupation with the baby, including the amount of time spent thinking about and talking to it. Responses are identified on a 5-point Likert-type scale (range of possible total scores is 19–95), with higher values indicating greater antenatal attachment. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients are reported to be 0.90 for quality and 0.76 for intensity.

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID) is a clinician-administered, semi-structured interview developed to facilitate diagnosis from a range of symptom-based psychiatric disorders as identified in the Diagnostic Manual of Mental Disorders-IV (APA, 2000). Organized in disease-specific modules, this instrument is widely used in North American research.29 With the exception of Dysthymic Disorder, test reliability was good to excellent (kappas ranging from 0.60 to 0.86) in diagnostic categories contained in the anxiety and mood disorder modules.30 The Mood Disorders module of the SCID was administered to establish or rule out a diagnosis of Major Depressive Disorder.

Pregnancy risk was assessed with a revision of the Hobel Risk Assessment for Prematurity (Hobel), an instrument assigning prescribed scores to 126 medical and obstetric risk factors of mother and neonate.31 Thirty-six intrapartum factors from the original scale and four additional items (premature rupture of the membrane, primary dysfunctional labor, placenta previa, and placental abruption) are coded with weighted scores 1, 5, or 10 based on their association with perinatal mortality. For example, “family history of diabetes” receives a score of 1, whereas insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus receives a score of 10. Previous studies have fixed the score of 10 or greater as indicative of higher risk.4

Procedures

Study investigators visited patients in their hospital rooms within 72 hours of admission, introducing the research as an investigation of women’s experiences during hospitalization and after childbirth. After the process of consent, each participant was interviewed for demographic information (see Tables 1 and 2 for variables) and presented with a packet of self-report measures. While participants completed the measures, a research investigator reviewed the medical chart to record necessary information regarding the health of mother and fetus and to complete the Hobel Risk Assessment scale.

Table 1.

Demographics of sample

| Study Sample | 2004 US Census | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percent | Percent | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| African American | 44 | 34.1 | 12.3 |

| Asian | 2 | 1.6 | 3.6 |

| Caucasian | 69 | 53.5 | 75.1 |

| Latino | 14 | 10.9 | 12.5 |

| Marital Status | |||

| Single | 38 | 29.5 | 32 |

| Married | 66 | 51.2 | 55.3 |

| Separated | 4 | 3.1 | 2.8 |

| Cohabiting | 14 | 10.9 | 15.7 |

| Missing | 7 | 5.4 | |

| Years of schooling completed | |||

| Not a HS | |||

| graduate | 17 | 12.4 | 19.9 |

| HS or equiv | 31 | 24.0 | 28.9 |

| Some college | 44 | 34.1 | 17.9 |

| College degree | 34 | 26.4 | 33.2 |

| Missing | 3 | 2.3 | |

| Occupational Status | |||

| Unemployed | 48 | 37.2 | 51.3 |

| On leave | 37 | 28.7 | N/A |

| Employed PT | 8 | 6.2 | 13.9 |

| Employed FT | 32 | 24.8 | 34.8 |

| Missing | 4 | 3.1 | |

| Average Household Income | |||

| Under $12,000 | 10 | 7.8 | |

| $12,000–25,000 | 31 | 24.0 | |

| $26,000–40,000 | 24 | 18.6 | |

| $41,000–65,000 | 20 | 15.5 | |

| Over $66,000 | 37 | 28.7 | |

| Missing | 7 | 5.4 | |

| US Census data (Dye, 2005) | |||

Table 2.

Pregnancy Characteristics of Participants

| Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|

| Total prior pregnancies | ||

| 0 | 35 | 27.1 |

| 1 | 32 | 24.8 |

| 2 | 25 | 19.4 |

| 3 | 17 | 13.2 |

| 4 or more | 18 | 14.2 |

| Missing | 2 | 1.6 |

| Prior full term pregnancies | ||

| 0 | 75 | 58.1 |

| 1 | 32 | 24.8 |

| 2 | 9 | 7.0 |

| 3 | 3 | 2.3 |

| 4 or more | 5 | 4.0 |

| Missing | 5 | 3.9 |

| Prior premature births | ||

| 0 | 87 | 67.4 |

| 1 | 33 | 25.6 |

| 2 | 3 | 2.3 |

| 3 | 1 | 0.8 |

| Missing | 5 | 3.9 |

| Number of prior live births | ||

| 0 | 50 | 42.7 |

| 1 | 33 | 28.2 |

| 2 | 12 | 10.3 |

| 3 | 6 | 5.1 |

| 4 or more | 6 | 5.2 |

| Missing | 3 | 2.3 |

| Number of prior stillborn | ||

| 0 | 119 | 92.2 |

| 1 | 6 | 4.7 |

| Missing | 3 | 2.3 |

| Prior spontaneous abortions | ||

| 0 | 84 | 65.1 |

| 1 | 29 | 22.5 |

| 2 | 6 | 4.7 |

| 3 | 5 | 3.9 |

| 5 | 1 | 0.8 |

| Missing | 4 | 3.1 |

| Prior terminations | ||

| 0 | 115 | 89.1 |

| 1 | 6 | 4.7 |

| 2 | 4 | 3.1 |

| Missing | 4 | 3.1 |

Any participant scoring at or above the established symptom threshold of 11 on the EPDS was scheduled to receive an administration of the Mood Disorder module of the SCID within approximately 48 hours. The interviews were conducted by postdoctoral and doctoral-level clinical psychology graduate students trained in SCID administration who also met periodically to monitor interrater agreement.

Data analyses

Relationships between the primary measures of relationship satisfaction (DAS), maternal fetal attachment (MAAS), and depressive symptoms (EPDS) were explored by rho correlations and contingency tables. Frequencies and proportions of the number of participants scoring over the threshold of the EPDS were tabulated. The relationship between the EPDS (a screening tool) identification of “depressed” versus “nondepressed,” and the SCID Mood Disorder module (a diagnostic tool) designation of “criteria met” versus “criteria not met” for MDD was compared for agreement by computing kappa. In addition, possible associations between the primary measures with demographic characteristics were analyzed by rho correlations. Significance was set at 0.05, and statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS Version 14 for Windows.

Results

Demographics

Table 1 contains the demographic information of the sample compared to the 2004 U.S. Census data. Participants’ average age (median = 27 years, range 17–44) was broadly similar to those participants represented in other research.6, 32 Importantly, unlike many samples in the literature consisting primarily of married Caucasian women, this group of women reflects the diversity found in the United States. In addition, the permissive inclusion criteria allowed gathering information across primagravidas (N = 50) and multigravidas (N = 56; Table 2) with a variety of obstetric complications (Table 3).

Prevalence of Depression

Overall, 44.2% (57/129) reported clinically significant symptoms of depression, based upon a threshold score of 11 by the EPDS. Twenty-four women (42%) scoring over the threshold on the EPDS were delivered or discharged before a SCID could be administered. Out of the remaining 33 participants who received a SCID, 25 women identified by the EPDS (75.8%) met criteria for MDD and 8 (24.2%) did not. The prevalence of MDD in the entire sample was at least 19.4% (25/129), without an accounting for patients with EPDS scores exceeding 11 who could not be followed with a SCID due to delivery or early hospital discharge. Kappa (agreement) between the EPDS screening threshold of 11 and the subsequent criterion-based diagnoses of depression (SCID) was strong: κ = .79, df = 1, p < .0001. Table 4 presents the means and standard deviations of the study measures.

Table 4.

Means and Standard Deviations of Measures

| N | Mean | SD | Range | Median | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mother’s age at interview | 128 | 27.5 | 6.4 | 17–44 | 27.0 |

| Gestational Age at Admission | 129 | 28.2 | 5.2 | 7–38 | 29.1 |

| EPDS | 129 | 9.5 | 5.9 | 0–23 | 9.0 |

| MAAS Global | 129 | 78.0 | 6.9 | 59–91 | 79.0 |

| Intensity | 127 | 31.0 | 4.7 | 17–40 | 31.0 |

| Quality | 128 | 46.0 | 3.6 | 33–50 | 47.0 |

| Hobel Risk Assessment | 128 | 20.9 | 11.3 | 5–57 | 20.0 |

| DAS | 128 | 112.4 | 21.6 | 16–143 | 117.0 |

EPDS: Edinburgh Depression Scale

MAAS: Maternal Antenatal Attachment Scale

Hobel: Hobel Risk Assessment for Prematurity

DAS: Dyadic Adjustment Scale

Obstetric Risk

Among the presenting obstetric risks, premature rupture of membranes, incompetent cervix, and preterm labor had the highest representation within the sample (23%, 27%, and 43%, respectively). One complication, incompetent cervix, was weakly associated with EPDS scores equal to or greater than 11, (χ2 = 4.75, df = 1, p = .029, Φ = 0.194).

Outside of certain expected demographic characteristics (age, parity, and gestational age) the only measure significantly associated with severity of obstetric risk (Hobel scale) was relationship satisfaction reported by the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS; rho = −.26, df = 116, p = .005). No significant relationship was found between severity of obstetric risk and reported maternal fetal attachment.

Relationship Satisfaction

In addition to a negative relationship with obstetric risk, relationship satisfaction was negatively associated with depressive symptomatology, parity (Table 5), and a history of prior premature births (rho = −.32, df = 116, p = .001). Contrastingly, positive associations were found between relationship satisfaction and maternal antenatal attachment (rho = .23, df = 116, p = 0.01), mother’s age (rho = .21, df = 116, p = .026), and average household income (rho = .30, df = 116, p = .002). Out of 118 women who reported being in a “committed relationship,” 38 were not cohabiting with their partner. When the cohabiting group of 80 was isolated and post hoc analyses conducted, only two variables were significantly associated with relationship satisfaction: severity of risk (rho = −.33, df = 78, p = .003), and parity (rho = −.28, df = 78, p = .01).

TABLE 5.

Rho correlations of measures with severity of risk and estimated gestational age *

| MAAS | EPDS | Hobel | Weeks | Parity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAS | rho | 0.23 | −0.21 | −0.26 | −0.02 | −0.21 |

| p | 0.01 | 0.02 | .005 | 0.83 | 0.02 | |

| MAAS | rho | −0.33 | −0.13 | 0.25 | −0.02 | |

| p | < .001 | 0.15 | .004 | 0.87 | ||

| EPDS | rho | 0.13 | −0.11 | 0.02 | ||

| p | 0.14 | 0.22 | 0.87 | |||

| Hobel | rho | −0.20 | 0.44 | |||

| p | 0.02 | < .001 | ||||

| Weeks | rho | 0.09 | ||||

| p | 0.34 | |||||

N = 129 except for DAS, where N = 118 and Hobel, where N = 128

DAS: Dyadic Adjustment Scale (Higher values indicate greater satisfaction)

MAAS: Maternal Antenatal Attachment Scale (Higher values indicate stronger attachment)

EPDS: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (Higher values indicate more depressive symptoms)

Hobel: Hobel Risk Assessment for Prematurity (Higher values indicate greater risk for maternal or fetal demise)

Weeks: Estimated gestational age at admission (birth at 37 weeks considered premature)

Parity: Number of previous live births

Antenatal Attachment

Antenatal attachment was negatively associated with severity of depressive symptoms (rho = −0.33, df = 127, p < .0001), but positively associated with the estimated gestational age of the baby (rho = .25, df = 127, p = .004). There were no significant relationships between strength of attachment and any demographic variables.

Two-way contingency tables, dividing the MAAS scores into the subscales of Quality and Intensity and EPDS scores under and at/over the threshold of 11, found a significant association between attachment quality and depressive symptoms (χ2 = 14.7, df = 1, p <.0001, Φ = 0.34), and a trend for association between attachment intensity (preoccupation), and depression (χ2 = 3.6, df = 1, p = .058, Φ = 0.17).

Additional Factors

A Pearson’s chi-square analysis was examined for potential associations between higher depressive symptomatology (categorized as EPDS ≤ 10 or ≥ 11) and any previous psychiatric diagnosis. This relationship was not significant (χ2 = 2.43, df = 1, p = .119, Φ = 0.14), nor were significant associations found between higher depressive symptomatology and family history of psychiatric illness (χ2 = .40, df = 1, p = .530, Φ = 0.056) or with parity (categorized as 0 or ≥1 pregnancy; χ2 = .58, df = 1, p = .45, Φ = 0.068). A closer investigation of the sample reveals 24% (30/124) of the participants reported they had history of receiving a psychiatric diagnosis (MDD, Bipolar Disorder, one of the anxiety disorders, or MDD comorbid with an anxiety disorder), and five of these endorsed a previous psychiatric hospitalization. Among the five, four had EPDS scores greater than 11 and, of the three receiving a clinical interview, all fulfilled the SCID criteria for MDD.

Annual household income was significantly associated with depressive symptom severity as rated by the EPDS (rho = −.22, df = 121, p = .015), as was a Pearson’s chi-square analysis focusing upon those with incomes under $25,000 and those reporting higher depressive symptomatology (χ2 = 5.10, df = 1, p = .024, Φ = 0.204). A significant negative relationship was found between higher depressive symptoms and absence of insurance coverage (χ2 = 5.67, df = 1, p = .017, Φ = −0.212). Of sixty-one patients without private insurance, only 20 had EPDS scores of 11 or higher (32.7%), but 35 of the 65 patients who reported having insurance also reported elevated depressive symptoms (53.8%). Income and insurance coverage were highly associated (rho = .70, df = 121, p < .000), as were household income and education (rho = .50, df = 121, p < .000), and insurance and education (rho = .45, df = 125, p < .000). Prenatal attachment scores on the MAAS were not significantly related to either income or insurance coverage.

Discussion

Prevalence of Major Depressive Disorder

In regard to the primary aim of investigating the prevalence of MDD in a sample of hospitalized pregnant women, the data indicated the proportion of those with MDD was at least 19%, higher than reported in other studies of perinatal women.17, 20 Based upon the strong agreement between higher EPDS scores and SCID-diagnosed MDD in the subset of women who received clinical interviews, it is likely that the actual prevalence rate is much higher than 19%. It should also be emphasized that the participants who met the SCID criteria for depression experienced onset at some point prior to hospitalization (they were interviewed within the first few days of hospitalization yet fulfilled the necessary two-week duration of symptoms over the preceding month). This finding suggests that in these women mood disruption existed prior to the stress of hospitalization. Importantly, almost half of the total sample (44%) reported elevated levels of depressive symptomatology on the EPDS, which identifies them as also at risk for MDD during the postpartum period.16, 17 This is also a higher proportion than reported by other investigators screening for antepartum depression.33

Screening and SCID DSM-IV Diagnosis

Choosing an EPDS threshold at screening that is most predictive of diagnosis for MDD has been discussed at length by Gaynes et al. (2004). Lower thresholds (scores of 9–10) on the EPDS are more sensitive and miss few cases of MDD, but have the disadvantage of poorer specificity or signaling “false positives,” cases who do not meet the criteria for MDD. Higher thresholds (12–13) have the opposite problem; high specificity proves to identify readily those women who meet the criteria for MDD but misses a number who may report less severe symptoms but do meet the criteria upon interview. In the subset of women who received a SCID, the threshold score of 11 accurately predicted six cases of MDD, which supports the suggestion made by Adouard et al. that the threshold of 12 may be optimum for non-complicated pregnancies but not sensitive enough for those diagnosed as high-risk.13 With this in mind, a screening measure such as the EPDS is an important tool to indicate when a psychiatric consultation for correct diagnosis and treatment planning should be added to appropriate hospital care during pregnancy.

Obstetric Risk and Depressive Symptoms

Almost half of this sample reported a level of depressive symptomatology considered significant by the EPDS, and at least 1 out of 5 women met the full criteria for MDD. Unlike previous research, the severity of obstetric risk was not associated with the severity of depressive symptoms in this sample of hospitalized women.4 However, the Maloni group4 employed an outcome measure that incorporated depression, anxiety, and hostility, whereas this discussion focused upon depression. Severity of risk aside, this sample strongly suggests that women with obstetric risk are particularly vulnerable to depression. When specific risk factors were introduced into the analysis, incompetent cervix was positively correlated with EPDS scores. With the exception of hypertension and preeclampsia, little has been published about the relationships of specific complications such as these with depression. Often incompetent cervix is diagnosed early in the second trimester and bed rest, a prescription previously associated with depressed mood, is recommended for the duration of the pregnancy.4 Long-standing complications paired with the additional finding that depressive symptoms preexisted hospitalization in this group of women also supports previous published associations between depression and preterm, low birthweight infants.34, 35 Sample size recommends caution in interpretation, but the association between a risk factor named “incompetent cervix” and low mood could also be a signal that the type of complication may have additional psychological meaning to the expectant mother and affect the beliefs she holds about the risk to her and her baby. Though no definitive statements can be made solely on the basis of this sample, the possibility that depression itself may be a risk factor for certain obstetric complications is worth continued consideration.

Relationship Dissatisfaction

The second aim of the project was to investigate associations between psychosocial and demographic risk factors for depression previously found in women with uncomplicated pregnancies. Relationship dissatisfaction has been linked with depression in uncomplicated pregnancy and the postpartum in multiple studies. A synthesis of recent work reported a moderate effect size of Cohen’s d of 0.39, placing this element in the top ten risk factors for postpartum depression.16 Findings in this sample of women are that lower relationship satisfaction is not only associated with higher depressive symptomatology, but also associated with higher maternal fetal risk scores and higher parity. Dovetailing with this finding is the statistically significant positive relationship between maternal antenatal attachment and relationship satisfaction, suggesting that there is a complex relationship between a mother’s attachment to her fetus, satisfaction with her partner, and symptoms of depression. This broadens the lens from focusing on women who are depressed (and possibly stigmatizing them) to looking at the couple and the relationship into which a baby will be introduced. The results of this study agree with other reports that women with obstetric risk have an enhanced vulnerability to perinatal depression, and prophylactic treatment during hospitalization might do well to include partners.

Since some of these same associations were not supported in a post hoc analysis of only cohabiting women, some factor of those committed relationships that occurs outside of cohabitation confounded the analysis. Nevertheless, this suggests that women hospitalized with obstetric risk perceive their relationships as less satisfying, and the presence of other children is also implicated in this distress. Similar findings of family stress during antepartum bed rest are published in the nursing literature.7, 9

Depressive Symptoms and Prenatal Attachment

Previous findings associating prenatal attachment with depressive symptoms have been equivocal. One investigative team found a weak inverse correlation between maternal fetal attachment in women with uncomplicated pregnancies (r = −0.17, p < 0.05), but did not find the same relationship in women with obstetric risk.11 A second team reported that the level of self-reported depression in healthy pregnant women accounted for only 3% of the variance in prenatal attachment.36 It has also been suggested that higher maternal fetal attachment serves as a moderator in those vulnerable to depression, a possible explanation for why all women with history or risk for postpartum depression do not become depressed.37 Although still modest, the association in this sample of hospitalized women was greater than that reported by other studies; approximately 11% of the variance in prenatal attachment can be explained by higher levels of depressive symptoms. Further statistical analysis drew attention to the significant relationship between the component “Quality” of attachment and reported depressive symptoms. Higher quality of maternal fetal attachment was reported by more than twice as many women in the depression subthreshold group compared to those scoring over 11 on the EPDS (49:19).

Demographic Factors

Inconsistent with previous perinatal research, the women in this sample with a personal or family history of psychiatric distress were no more at risk for higher depressive symptomatology than those with no such history.17 Nevertheless, the finding that most of those with history of psychiatric hospitalization fulfilled the SCID criteria for MDD encourages careful psychiatric history-gathering by clinicians, in order to identify early those most vulnerable to a depressive episode during pregnancy. Lower socioeconomic status has also been repeatedly linked with depression during pregnancy and in the postpartum, and income was weakly associated in this sample of women.35 Education and insurance coverage, two other measures of socioeconomic status, were not associated with depressive symptoms. In the subgroup of women who had no private insurance, less than half had elevated EPDS scores (20/61) while more than half of the insured group had scores at or above 11 (35/65). A potential explanation for this finding is that these women may have less negative perceptions of hospitalization in view of their greater socioeconomic needs for care.

Limitations

This research is of value in looking at the proportion of women who scored over the threshold of 11 on the EPDS screening tool. Due to the unpredictable nature of an antepartum unit, it was not possible to clinically interview all participants, preventing a definitive statement regarding the use of this threshold. Nevertheless, the relatively high prevalence rate of MDD found in this sample of women advises regular screenings for depression on antepartum units and recommends a conservative symptom threshold on the EPDS.

Due to HIPAA regulations, no chart abstraction was permitted for subjects who refused, so nothing can be said about women who met the inclusion criteria but refused to participate in the study. However, the possibility that depression was a component of refusal cannot be disregarded. The protocol required two face-to-face interviews and the completion of a packet of self-report measures, a process that may have seemed overwhelming to patients already overwhelmed with the implications of their obstetric complications and the effect of hospitalization upon their spouses and families. In fact, the three participants who withdrew from the project cited “not feeling like doing it” as their reason for withdrawal.

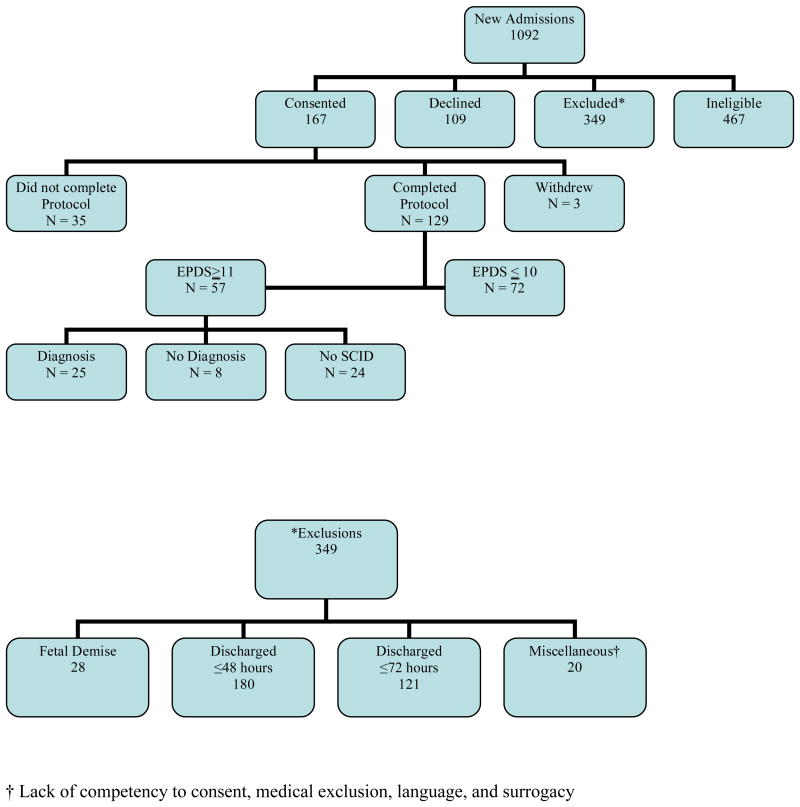

Conducting pure research in a hospital unit such as the setting for this study and with a population such as this one is a challenging task. The process of pregnancy and childbirth has always been unpredictable, which is illustrated by the rate of exclusions that occurred because mothers either delivered or were discharged within 72 hours of admission, even when this was not expected (see Figure 1). Future investigations in this environment would be enhanced by having a full-time research coordinator on site at the hospital.

Figure. 1. CONSORT.

Finally, no interrater data from the SCID interviews were collected. The interviewers met at intervals, viewed and rated a videotape or role-played interview, and discussed ratings but, unfortunately, these data were not preserved.

Implications for future research

The rate of depressive symptomatology found in this sample recommends further investigation in larger samples. Additional knowledge concerning the interplay of these psychosocial risk factors, depression, and obstetric complications would enable trials of early intervention that could possibly modify the outcome of obstetric risk factors, further elucidating the associations in the process. For example, the recent application of attachment theory to multiple disciplines has stimulated the development of innovative attachment-based interventions. Such an approach could directly target antenatal depression through the lens of one of its risk factors. Taking the couple’s relationship into consideration would address the natural changes in the dyadic relationship parenthood brings, and interventions may be benefited by incorporating the partner in the treatment.38 Given the family strains of high-risk pregnancy, increasing partner support and understanding is essential. Although the underlying mechanisms of depression are not thought to be different in pregnancy than any other period of life,39 the particular demands of the physical and emotional changes during complicated pregnancy may necessitate flexibility not only in psychotherapeutic approaches but also in the locations where interventions are employed. Incorporating psychosocial interventions in antepartum units or in obstetric clinics would expedite treatment and could possibly improve participation rates and minimize the stigma of needing such an intervention. Projects investigating the addition of screening and intervention on high-risk antepartum hospital units would enable explorations of the impact of treatment upon preterm births and length of hospital stays. Empirical trials of innovative approaches to depression during pregnancy to increase knowledge and confidence in psychotherapeutic alternatives to pharmacological treatment are necessary, as is data reporting any postpartum effects of antepartum intervention. As has been iterated in other publications, longitudinal work is essential in this area if we are to identify efficacious ways to address depression during pregnancy and in the postpartum.

Conclusion

Forty-four percent of the women in this sample reported clinically significant symptoms of depression, and the prevalence rate of Major Depressive Disorder is at least 19%, higher than that previously reported in women experiencing normal pregnancies. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale scores of 11 and greater are in high agreement with a SCID-based diagnosis of MDD (κ = .79, df = 1, p < .0001), confirming the value of this screening instrument and supporting previous recommendations for this threshold with high-risk pregnant women. Given these numbers, screening for depression in women hospitalized for obstetric risk is recommended. When depression is suspected, psychiatric consultation for diagnosis and treatment is a necessary component of prenatal care. Corroborating previous work, prenatal depression is significantly associated with psychiatric history, lower maternal fetal attachment, and higher relationship dissatisfaction.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Dr. John Rosnes and the staff at Baylor University Medical Center for their support throughout the data gathering phase of this research. This project also benefited from two clinical advisors, H. M. Evans, Ph.D. and Sandra Pitts, Ph.D., both of UT Southwestern Medical Center, and one research advisor, Richard Robinson, Ph.D. of Baylor University Medical Center. A. John Rush, M.D. of UT Southwestern Medical Center provided direction in manuscript preparation. In addition, one predoctoral graduate student, Cindy D. Huntzinger, B.A., and four volunteers were instrumental in initiating and carrying out the work: Daria Dato, MSSW, Missy Heusinger, M.A., Georgina Rangel, B. A. and Laura Rowley, B. A. Statistical analyses and first author’s time were supported in part by NIH K12 RR023251.

References

- 1.Lumley J. Defining the problem: The epidemiology of preterm birth. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2003;110(Suppl 20):3–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Penticuff JH. Psychologic implications in high-risk pregnancy. Nursing Clinics of North America. 1982;7(1):69–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Unauthored. Perinatal Data Snapshots. 2007 March 2007 [cited 2007 April 30, 2007] Available from: www.marchofdimes.com/peristats.

- 4.Maloni JA, Kane JH, Suen L, Wang KK. Dysphoria among high-risk pregnant hospitalized women on bed rest: a longitudinal study. Nursing Research. 2002;51(2):92–99. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200203000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heaman M, Gupton A, Gregory D. Factors influencing pregnant women’s perceptions of risk. MCN: The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing. 2004;29(2):111–116. doi: 10.1097/00005721-200403000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heaman M. Stressful life events, social support, and mood disturbance in hospitalized and non-hospitalized women with pregnancy-induced hypertension. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research. 1992;24(1):23–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maloni JA, Brezinski-Tomasi JE, Johnson LA. Antepartum bed rest: effect upon the family. JOGNN: Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing. 2001;30(2):165–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2001.tb01532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stainton MC, McNeil D, Harvey S. Maternal tasks of uncertain motherhood. Maternal-Child Nursing Journal. 1992;20(34):113–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maloni JA, Ponder MB. Fathers’ experience of their partners’ antepartum bed rest. Image: Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 1997;29(2):183–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1997.tb01554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chazotte C, Freda MC, Elovitz M, Youchah J. Maternal depressive symptoms and maternal-fetal attachment in gestational diabetes. Journal of Women’s Health. 1995;4(4):375–380. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mercer RT, Ferketich S, May K, DeJoseph J, Sollid D. Further exploration of maternal and paternal fetal attachment. Research in Nursing & Health. 1988;11(4):269–278. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770110204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dulude D, Belanger C, Wright J, Sabourin S. High-risk pregnancies, psychological distress, and dyadic adjustment. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. 2002;20(2):101–123. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adouard F, Glangeaud-Freudenthal NMC, Golse B. Validation of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS) in a sample of women with high-risk pregnancies in France. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2005;8:89–95. doi: 10.1007/s00737-005-0077-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kurki T, Hiilesmaa V, Raitasalo R, Mattila H, Ylikorkala O. Depression and anxiety in early pregnancy and risk for preeclampsia. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2000;95(4):487–490. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00602-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chung T, Lau TK, Yip A, Chiu H, Lee D. Antepartum depressive symptomatology is associated with adverse obstetric and neonatal outcomes. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2001;63:830–834. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200109000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robertson E, Grace S, Wallington T, Stewart DE. Antenatal risk factors for postpartum depression: a synthesis of recent literature. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2004 Jul-Aug;26(4):289–295. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Hara MW, Swain M. Rates and risk of postpartum depression: A meta-analysis. International Review of Psychiatry. 1996;8:37–54. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gavin NI, Gaynes BN, Lohr KN, Meltzer-Brody S, Gartlehner G, Swinson T. Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Nov;106(5 Pt 1):1071–1083. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000183597.31630.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cox J, Holden J, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression: Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–786. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaynes BN, Gavin N, Meltzer-Brody S, et al. Perinatal depression: Prevalence, screening accuracy and screening outcomes. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2005. Report No.: Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cox J, Holden J. Perinatal mental health: A guide to the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) London: Gaskell; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heyman RE, Sayers SL, Bellack AS. Global marital satisfaction versus marital adjustment: An empirical comparison of three measures. Journal of Family Psychology. 1994;8(4):432–446. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spanier GB. Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1976;38(1):15–28. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spanier GB, Filsinger EE. The dyadic adjustment scale. 1983. pp. 155–168. [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Hara MW. Social support, life events, and depression during pregnancy and the puerperium. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1986;43(6):569–573. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800060063008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Hara MW, Schlechte JA, Lewis DA, Varner MW. Controlled prospective study of postpartum mood disorders: Psychological, environmental, and hormonal variables. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100(1):63–73. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Condon JT. The assessment of antenatal emotional attachment: Development of a questionnaire instrument. British Journal of Medical Psychology. 1993;66:167–183. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1993.tb01739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Condon JT, Corkindale C. The correlates of antenatal attachment in pregnant women. British Journal of Medical Psychology. 1997;70:359–372. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1997.tb01912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Summerfeldt LJ, Antony MM. Structured and semistructured diagnostic interviews. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown TA, Di Nardo PA, Lehman CL, Campbell LA. Reliability of DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders: Implications for the classification of emotional disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:49–58. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hobel CJ, Hyvarinen MA, Okada DM, Oh W. Prenatal and intrapartum high-risk screening: I. Prediction of the high-risk neonate. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1973;117(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(73)90720-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gupton A, Heaman M, Cheung LW. Complicated and uncomplicated pregnancies: women’s perception of risk. JOGNN: Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing. 2001;30(2):192–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2001.tb01535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Austin MP, Lumley J. Antenatal screening for postnatal depression: A systematic review. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavia. 2003;107:10–17. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.02024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Field T, Diego M, Dieter J, et al. Prenatal depression effects on the fetus and the newborn. Infant Behavior and Development. 2004;27:216–229. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Field T, Hernandez-Reif M, Diego M. Risk factors and stress variables that differentiate depressed from nondepressed pregnant women. Infant Behavior & Development. 2006 Apr;29(2):169–174. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lindgren K. Relationships among maternal-fetal attachment, prenatal depression, and helath practices in pregnancy. Research in Nursing & Health. 2001;24:203–217. doi: 10.1002/nur.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Priel B, Besser A. Vulnerability to postpartum depressive symptomatology: Dependency, self-criticism and the moderating role of antenatal attachment. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1999;18(2):240–253. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Whiffen VE, Johnson SM. An attachment theory framework for the treatment of childbearing depression. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2006;5(4):478–492. [Google Scholar]

- 39.O’Hara MW, Zekoski E, editors. Postpartum depression: A comprehensive review. London: Oxford University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]