Abstract

Since its inception, the amyloid cascade hypothesis has dominated the field of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) research and has provided the intellectual framework for therapeutic intervention. Although the details of the hypothesis continue to evolve, its core principle has remained essentially unaltered. It posits that the amyloid-β peptides, derived from amyloid precursor protein (APP), are the root cause of AD. Substantial genetic and biochemical data support this view, and yet a number of findings also run contrary to its tenets. The presence of familial AD mutations in APP and presenilins, demonstration of Aβ toxicity, and studies in mouse models of AD all support the hypothesis, whereas the presence of Aβ plaques in normal individuals, the uncertain nature of the pathogenic Aβ species, and repeated disappointments with Aβ-centered therapeutic trials are inconsistent with the hypothesis. The current state of knowledge does not prove nor disprove the amyloid hypothesis, but rather points to the need for its reassessment. A view that Aβ is one of the factors, as opposed to the factor, that causes AD is more consistent with the present knowledge, and is more likely to promote comprehensive and effective therapeutic strategies.

Introduction

With a rapidly aging population in the developed world and increasing life expectancy in the developing world, Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is becoming a growing problem around the globe. AD is a slowly progressing, heterogeneous neurodegenerative disorder of uncertain etiology. Neurologically, it is initially manifested as a series of mild cognitive impairments, deficits in short-term memory, loss of spatial memory, and emotional imbalances. As the disease progresses, these symptoms become more severe, and ultimately result in total loss of executive functions. Pathologically, the disease is characterized by the presence of extracellular plaques of amyloid-β peptides (Glenner and Wong, 1984a, b; Masters et al., 1985) and intracellular tangles of hyperphosphorylated tau protein (Ballatore et al., 2007; Braak and Braak, 1998). The spatial and temporal connections between these two pathological hallmarks are not completely understood. The plaques first appear in the frontal cortex, and then spread over the entire cortical region, while hyperphosphorylated tau and insoluble tangles initially appear in the limbic system (entorhinal cortex, hippocampus, dentate gyrus) and then progress to the cortical region. The pioneering work of Braak and Braak suggests that the tangles appear before the plaque deposition is observed in AD brains, and that tangle pathology is more closely associated with disease severity than the plaque load (Braak and Braak, 1998; Giannakopoulos et al., 2003; Gosche et al., 2002; Josephs et al., 2008).

About 5% of AD cases are ‘familial’ (fAD) with mutations found in amyloid precursor protein (APP) or in presenilin genes. Presenilin 1 (PS1) and presenilin 2 (PS2) are the catalytic core of the γ-secretase complex (De Strooper, 2003; Selkoe and Wolfe, 2007), and they cleave APP within the membrane-spanning domain generating Aβ peptide and APP intracellular domain (AICD). Little is known about the biological significance of AICD other than that it possesses transcriptional regulatory activity (Cao and Sudhof, 2001; Gao and Pimplikar, 2001; Zhang et al., 2007) and alters signaling pathways (Leissring et al., 2002; Ma et al., 2008; Ryan and Pimplikar, 2005). Most mutations in APP or presenilin invariably alter APP processing, often resulting in increased levels of longer form of Aβ (Aβ42). The Aβ42 peptide is more prone to aggregate and to form plaques, which are also frequently found in the brains of patients with sporadic AD. The familial AD afflicts patients in the 4th or 5th decade of life, whereas the sporadic AD cases are found in people in their 7th or 8th decade. Other than the age of onset, both forms of AD show similar neurological and histopathological features, and are thought to represent the same disease. Both APP and tau are integral to AD pathogenesis; mutations in APP and PS1 cause AD, and tau tangles are better correlated with the disease severity.

The Amyloid cascade hypothesis and its many avatars

Although the exact cause of AD has been the subject of considerable debate, the amyloid hypothesis remains the best defined and most studied conceptual framework for AD. The presence of amyloid plaques, as originally described by Alois Alzheimer in 1907, is considered as the defining characteristic of AD. Identification of Aβ peptides, the major constituents of the plaques, as the proteolytically derived products of APP (Glenner and Wong, 1984a, b) and cloning of the APP gene (Kang et al., 1987) allowed the disease to be examined at biochemical and molecular levels. Subsequently, mapping of several fAD mutations to the APP gene (Owen et al., 1990), the association of AD with Down’s syndrome (which results from trisomy 21 and APP gene locus is present on chromosome 21), and higher prevalence of AD with increased copy number of APP, all established the primacy of APP in AD pathogenesis (Glenner and Wong, 1984a; Rovelet-Lecrux et al., 2006; Sleegers et al., 2006). The central role of APP in AD etiology was further confirmed by the identification fAD mutations in PS1, which cleaves APP and generates Aβ and AICD.

As originally proposed in the early 90’s (Hardy and Higgins, 1992; Selkoe, 1991), the essence of the amyloid hypothesis is that the increased production or decreased clearance of Aβ peptides causes the disease. Accumulation of the hydrophobic Aβ40 and Aβ42 peptides results in aggregation and formation of insoluble plaques, which trigger a cascade of deleterious changes, resulting in neuronal death and thus causing AD. Over time, this hypothesis has undergone alterations primarily in the description of the nature of pathogenic Aβ that is proposed to initiate deleterious events and cause AD (Figure 1). The original idea that the plaques are pathogenic has currently fallen out of favor because of two primary reasons. First, as indicated earlier the plaque load does not correlate well with the degree of dementia in humans (Terry et al., 1991), and many AD patients with severely impaired memory show no plaques at post mortem analysis. Moreover, many mouse models of AD show memory deficits long before the plaques are observed in the brain (Lesne et al., 2008). Second, recent advances in neuroimaging techniques in vivo (such as 11C-PiB retention) have shown the presence of robust plaques in otherwise cognitively normal people (Nordberg, 2008; Villemagne et al., 2008). Although it is possible that the PiB-positive individuals may represent individuals who are at high risk for AD, these findings, at a minimum, show that the presence of plaques does not necessarily equate with memory deficits. These observations have led to thinking that perhaps the insoluble plaques do not trigger the pathological events, and may be benign or even protective in nature (Caughey and Lansbury, 2003). There is also emerging interest in the observations that Aβ accumulates intracellularly in mouse models of AD and in human AD brains and could contribute disease progression (Gouras et al., 2000; Knobloch et al., 2007; LaFerla et al., 2007). However, much remains to be known about its abundance relative to extracellular deposits, its location (intracytoplasmic or intravesicular), and how it could trigger the toxic effects.

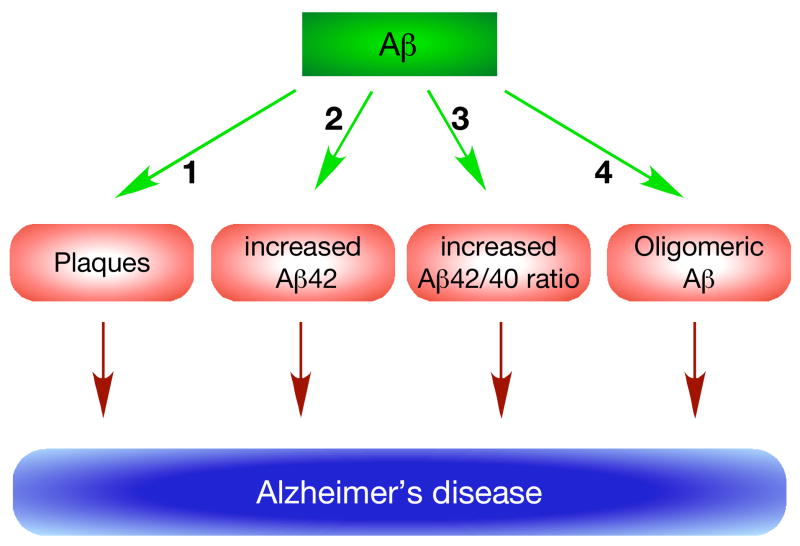

Figure 1. Many avatars of the amyloid hypothesis.

The main tenet of the amyloid hypothesis is that Aβ is the primary cause of the disease. It was originally proposed that increased levels of Aβ resulted in plaque formation (1), which caused AD. Subsequent observations that fAD mutations increase Aβ42 generation, led to a proposal that it is the increased levels of Aβ42 peptide that is pathogenic and caused AD (2). Another variation on the theme is that the absolute levels of Aβ42 are less important than the ratio of Aβ42/40 in causing AD (3), and there seems inverse correlation between Aβ42/40 ratio and the age of disease onset. However, the currently most favored idea is that Aβ forms soluble oligomers (4), which are pathogenic in nature and cause AD. Despite intense investigations, there is no consensus regarding the chemical nature of such pathogenic oligomers.

A large portion of the fAD cases is accounted for by mutations in the PS1 gene (Cruts and Van Broeckhoven, 1998). PS1, a membrane protein with multiple spanning domains, associates with three other membrane proteins to form the γ-secretase complex. Unlike in APP, the fAD mutations in PS1 are scattered over the entire length of the molecule. Many of these mutations result in altered cleavage of APP, causing increased production of the longer Aβ42 peptide, which is more prone to aggregate (Suzuki et al., 1994) and is shown to be more toxic in vitro. Since Aβ42 levels are found to be higher in AD patients, it was proposed that increased levels of Aβ42 triggered the cascade of the deleterious events resulting in AD (Younkin, 1995). Although, many fAD mutations in APP or PS1 result in increased Aβ 42, some mutations in PS1 do not increase the Aβ42 levels, but rather decrease the Aβ40 levels. This has led to yet another proposal that an increase in the 42/40 ratio, rather than the absolute levels of Aβ42, is pathogenic, and triggers the deleterious events leading to the disease. This view is supported by the observation that increased 42/40 ratio is generally inversely related with the age of onset of AD (Bentahir et al., 2006).

Finally, the latest idea that higher order soluble aggregates of Aβ – the oligomers – are the disease causing pathogenic agents has attracted a lot of interest (Glabe, 2005; Klein et al., 2001; Walsh and Selkoe, 2004, 2007). Many groups have identified a number of poorly characterized but biochemically distinct forms of Aβ oligomers, and demonstrated their toxicity using in vitro and in vivo model systems. Distinct oligomeric species have been isolated from the brains from mouse models of AD (Lesne et al., 2006) and also from human AD brains (Shankar et al., 2008). The latter study also showed that the dimeric oligomers isolated from human AD brains potently inhibited long-term potentiation and enhanced long-term depression with IC50 values in the picomolar range. Very little is known about how these distinct oligomers form in vivo, or whether Aβ42 oligomers are more toxic than Aβ40 oligomers, or how they trigger the deleterious changes.

From genetics to cell biology- evidence galore!

Studies from multiple disciplines have provided what seems like overwhelming support for the amyloid hypothesis. The supporting evidence has come from divergent areas such as genetics, histopathology, cell biology and animal models. These data have been discussed in detail in many excellent reviews (Crouch et al., 2008; Hardy and Selkoe, 2002; Price et al., 1998; Wakabayashi and De Strooper, 2008; Walsh and Selkoe, 2007; Yankner and Lu, 2008), and only the salient points are summarized below.

Genetics

Genetic studies of familial AD provide perhaps the strongest evidence supporting the amyloid hypothesis. Mutations in APP, PS1 and PS2 account for all the cases of fAD, whereas the E4 allele in the ApoE gene increases the risk of getting the disease. To date, approximately 180 fAD mutations have been identified in PS1, 20 fAD mutations in PS2 and 36 fAD mutations in APP (www.molgen.ua.ac.be/ADMutations). Most of the mutations in APP and presenilins seem to increase Aβ generation and/or increase Aβ42 levels. Mutations in APP are localized at or near the cleavage sites that give rise to Aβ, although some mutations are mapped in the middle of the Aβ peptide and are thought to increase fibrillization. Mutations in PS1 and PS2, unlike those in APP, are distributed throughout the molecule. The question whether these mutations represent a toxic gain-of-function or a loss-of-function of APP and presenilins remains unsettled (De Strooper, 2007; Hardy, 2007; Van Broeck et al., 2007; Wolfe, 2007).

Pathology

Histopathologically, Aβ plaques and tau tangles are considered the diagnostic hallmarks of AD. Thus, by definition Aβ plaques are the essential component of AD pathogenesis. Indeed, one carefully controlled study with low sample size showed strong correlation between cognitive dysfunction and Aβ plaques in the entorhinal cortex (Cummings et al., 1996). However, detailed examination of a large number of AD brains upon autopsy has shown that tau tangles appear initially in the limbic system of the brain and spread to the cortex as the disease progresses. Aβ plaques, on other hand, appear first in the cortical regions and spread to the rest of the brain as the disease progresses (Braak and Braak, 1998).

Cell Biology

Tissue culture studies in vitro have proved valuable in demonstrating the neurotoxic nature of Aβ peptides. A number of early studies showed that when added to neuronal cultures, fibrillar Aβ produced deleterious changes such as apoptosis, neuronal cell death, and synaptic and dendritic loss. By contrast, monomeric or non-fibrillar Aβ was incapable of producing such changes. These deleterious events were also observed in vivo when fibrillar Aβ was injected in mouse brains. However, as pointed out above recent studies have implicated the soluble oligomeric Aβ, rather than the fibrillar Aβ, to be the toxic moiety.

Animal models

Many groups have generated mouse models of AD that develop Aβ plaques and exhibit memory deficits. These transgenic mouse models, based on overexpression of fAD mutant APP or PS1 (or both), have yielded significant information on AD pathogenesis, and have been used to evaluate the efficacy of both immune and non-immune therapeutic strategies. In some cases, reduction in total Aβ or Aβ plaque load was accompanied by improved memory function in behavioral paradigms (Radde et al., 2008).

Would the real oligomers please stand up?

The idea of soluble ‘Aβ-oligomers’ as the toxic, disease-causing agent is receiving increasingly greater attention. Aβ peptides are amphiphilic in nature, with the first 28 residues being polar and last 12 (or 14 in Aβ42) being nonpolar. At neutral pH, the polar part of the peptide contains 6 positively charged and 6 negatively charged residues, further exaggerating the polarity of differences between two termini of Aβ. Because of this amphiphilic property, Aβ aggregates and forms higher-order oligomers in vitro (Bitan et al., 2003; Teplow et al., 2006). Such oligomers have also been isolated from culture medium (Walsh et al., 2005), brain extracts of AD patients (Shankar et al., 2008) or AD mouse models (Lesne et al., 2006). Yet, as discussed below, aggregation of the amphiphilic Aβ is extremely sensitive to experimental manipulations raising a possibility that the conclusions of some of the investigations may be open for interpretation.

The molecular pathway by which Aβ forms soluble oligomers and insoluble fibrils and protofibrils in vivo is not clear (Figure 2). The currently available information is based on two experimental approaches. The in vitro approach involves the use of synthetic Aβ peptides under controlled conditions (Teplow et al., 2006), whereas the in vivo approach relies on isolating such oligomers from tissue culture media, brain extracts, etc. The biophysical and computational approaches have revealed a complex pattern of Aβ assembly, and have uncovered subtle differences between oligomerization of Aβ40 vs. Aβ42 (Urbanc et al., 2004). A common picture emerging from the use of multiple experimental approaches suggests that Aβ exists in a ‘natively unfolded’ conformation, and undergoes nucleation-dependent polymerization. It is suggested that Aβ forms hexameric ‘paranuclear’ units, which self-associate end-on-end to form beaded protofibrils (Roychaudhuri et al., 2008). These protofibrils further aggregate to form fibrils, ultimately leading to plaque formation.

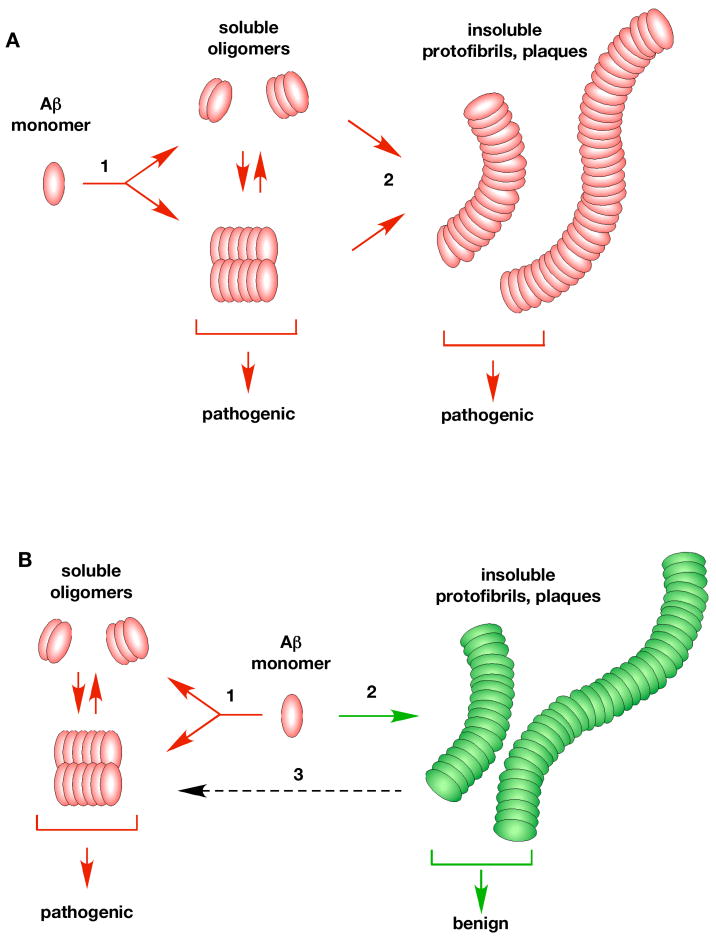

Figure 2. Potential pathways of Aβ oligomerization in vivo.

Almost nothing is known about how Aβ oligomerizes in vivo. One possibility (A) is that there is a single linear oligomerization pathway with Aβ monomers initially forming low molecular weight soluble aggregates (1). These oligomers further aggregate (step 2) into insoluble protofibrils, fibrils and plaques (2). In this view, both soluble oligomers and insoluble fibrils are considered to be pathogenic. An alternate possibility (B) is that there are two distinct pathways. A pathogenic pathway (1) that forms soluble oligomers (dimers/Aβ*56/ADDLs) which cause the disease, and a second non-pathogenic pathway (2) that leads to the formation of insoluble aggregates and plaques. The insoluble aggregates are thought to be benign, a view more consistent with the available data. It has also been suggested that the benign insoluble aggregates may slowly leach (3, dashed arrow) forming the pathogenic soluble oligomers (Meyer-Luehmann et al., 2008).

Using in vitro approaches, various groups have formed discreet oligomeric structures from pure, synthetic Aβ peptides. ADDLs (Aβ-derived diffusible ligands) are formed from Aβ42 using special solvent conditions, and seem to be composed of 12 monomers (Catalano et al., 2006; Klein, 2002; Roychaudhuri et al., 2008). By atomic force microscopy, these oligomers appear as globular structures of 6 nm. On the other hand, Aβ42 forms distinct 12-mer units in the presence of SDS called ‘globulomers’, with the C-terminal region of Aβ forming the hydrophobic core (Gellermann et al., 2008). However, these globulomers do not form fibrils. Larger Aβ-oligomers, comprising 15–20 monomeric units have also been formed in vitro (Deshpande et al., 2006). In addition, several larger assemblies that form pore-like structures with diameter up to 15 nm have been described in vitro using synthetic Aβ peptides (Hoshi et al., 2003). Thus, by employing different experimental conditions, distinct oligomeric structures can be formed from Aβ in vitro.

So, what happens under in vivo conditions? It is obvious that the in vivo environment is very different from that found in vitro, and the hydrophobic nature of Aβ makes it doubtful that the pathways of Aβ assembly observed in vitro also work in vivo. Not surprisingly, the Aβ oligomers isolated from the biological systems rarely resemble those formed in vitro from synthetic peptides. For example, the naturally secreted, Aβ-oligomers have been isolated from tissue culture media of cells stably expressing fAD mutant APPV717F protein. However, unlike the large oligomers formed in vitro (12-mers and larger), these oligomers are small, mostly dimers and trimers (Townsend et al., 2006). Such dimers and trimers have been reported in the brains of AD patients, but not normal individuals. Interestingly, the neurotoxicity was associated only with the Aβ dimers and not with the higher oligomers (Shankar et al., 2008). In contrast, another set of studies showed that neurotoxicity was associated not with the smaller dimeric/trimeric aggregates, but with much larger oligomers termed Aβ*56 (Cheng et al., 2007; Lesne et al., 2006). These oligomers, possibly composed of 12 monomers, are first observed in a transgenic mouse model at the approximate age when memory deficits become apparent. Unlike the pathogenic dimers/trimers, so far there have been no reports indicating the presence of Aβ*56 in AD brains but not normal brains.

While it is important to appreciate the technically challenging nature of the Aβ oligomerization studies, it should be recognized that they are fraught with experimental artifacts (Rahimi et al., 2008). In a series of careful studies, Teplow and colleagues showed how Aβ could be artifactually formed into oligomers simply by experimental manipulations (Bitan et al., 2005; Teplow et al., 2006). Thus, it remains a serious concern as to whether Aβ oligomers are induced during isolation procedures or actually pre-exist in the biological samples prior to the experimental manipulations. This argument becomes even more plausible (Rahimi et al., 2008) when one considers that different groups, employing different isolation procedures, arrive at different oligomeric structures from biological samples, e.g. Aβ*56 (Lesne et al., 2006) vs. dimers/trimers (Shankar et al., 2008) vs. the ADDLs (Catalano et al., 2006; Lesne et al., 2006; Shankar et al., 2008). Nonetheless, it is interesting that these groups were not able to isolate the respective oligomeric species from normal brains. Thus, formation of Aβ oligomers from the AD brains may not be simply due to the isolation protocols employed. In any case, from the discussion above it should become obvious that despite the growing attention, the biology and chemistry of ‘oligomeric Aβ’ is fraught with experimental artifacts increasing the odds of arriving at erroneous conclusions.

Reassessing the amyloid hypothesis: is the glass three-quarters full or the wrong size?

The amyloid hypothesis dominates the AD research field because it is the best described and most scrutinized model, and is supported by a large volume of data. Nevertheless, it is not universally accepted in the field, and if anything criticism of the hypothesis is becoming more pointed. One reason for this development is the accumulation of new data that are inconsistent with the main tenets of the hypothesis. Moreover, as discussed below, a strong case can be made that even the existing supporting data may not be as strongly supportive as initially perceived.

Genetics

The presence of mutations in APP and presenilins has been considered amongst the strongest evidence in support of the hypothesis (Hardy and Selkoe, 2002; Price and Sisodia, 1998) but they are not the evidence that Aβ is the prime cause of AD. Presently, over 225 fAD mutations in APP, PS1 and PS2 combined have been reported that initiate the disease at various ages. However, different mutations result in different molecular outcomes- some increase total Aβ, some increase Aβ42 selectively, some do not affect Aβ levels, while some others selectively decrease Aβ40 without affecting Aβ42 levels (Van Broeck et al., 2007). Similarly, with about 180 distinct mutations distributed throughout the PS1 molecule, it is difficult to see how all of them can result in a single molecular outcome, namely increase in Aβ42 levels (Shioi et al., 2007). Thus, taking into account that APP is the substrate and PS1 is the protease, the common denominator amongst all the mutations is that they alter APP processing, and increase in the Aβ42 levels is just one of the many possible consequences. This point of view remains consistent with the genetics of AD, but does reduce the importance of Aβ as a causative agent. In addition, many studies have shown that mutations in PS1, which account for the majority of fAD cases, also cause neuronal dysfunction by pathways that are independent of APP and Aβ (Baki et al., 2008; Baki et al., 2004; Kallhoff-Munoz et al., 2008; Neve, 2008; Shen and Kelleher, 2007; Shioi et al., 2007). Thus, there is a substantial body of data indicating that PS1 mutations by themselves can trigger the toxic events, and that the increased Aβ load and plaques may be a secondary effect, perhaps less consequential to disease causation and progression.

Pathology

The original tenet of the amyloid hypothesis that the plaques cause the disease is now falling out of favor. The shift in thinking can be traced to a number of factors. First, exhaustive histopathological observations showed a poor correlation of the ‘plaque load’ with the degree of dementia in AD patients (Terry et al., 1991). Second, the early observations that many non-demented normal individuals had significant plaque load upon autopsy has now been confirmed by live PiB imaging. Third, many mouse models of AD that overexpress fAD mutant APP show memory deficits prior to plaque depositions. The J20 transgenic mouse line expressing Swedish (K670N/M671L; numbering according to APP770) and Indiana (V717F) mutations shows robust plaque pathology and memory deficits. Interestingly, insertion of an additional mutation in the APP cytoplasmic tail (D664A; numbering according to APP695) ameliorated the memory deficits without any reduction in the plaque pathology (Galvan et al., 2006). This finding proves that plaques alone do not necessarily underlie memory deficits, as also confirmed in Tg2576 line, another mouse model of AD (Lesne et al., 2008). Finally, data from recent human studies showed that in a small number of AD patients, removal of the plaques by vaccination did not result in improved memory function (Holmes et al., 2008). Such findings, together with studies suggesting neurotoxicity is associated with the soluble oligomers of Aβ, have started to displace the notion that plaques are the cause of the disease.

Cell biology

A large body of evidence shows that synthetic Aβ, when added to neuronal cultures or injected into mouse brains, causes deleterious events such as activation of kinases, tau hyperphosphorylation, oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, apoptosis, etc. Thus, the toxic effects of Aβ are unambiguously demonstrated in various experimental paradigms. However, considering the amphiphilic structure of Aβ, which imparts detergent-like properties, the toxicity reported with Aβ peptides is not surprising. A more relevant pathophysiological question is-does this represent what could be happening in human AD? A vast majority of these studies have used micromolar or higher concentrations of purified Aβ40–42, which are orders of magnitudes higher than observed inside the body. Moreover, because of its hydrophobic nature, Aβ peptides inside an organism will not be free, but will be associated with other hydrophobic proteins. The disease relevance of several early studies conducted using Aβ 25–35 is even less clear since this peptide has not been observed inside a living organism (Du et al., 2007). Also, the ICV injection paradigm limits the relevance of the studies because it is difficult to imagine a pathophysiological situation where an organism receives such an acute bolus of purified Aβ. In short, although Aβ undoubtedly possesses toxic properties in vitro, it is difficult to prove that this is also true in the pathophysiological conditions in vivo that are relevant to AD.

Animal model of AD

Development of mouse models of AD that reproduce the major AD features, such as Aβ plaques and memory deficits, has yielded significant information about AD. Such models have been generally considered to be favorable to the amyloid hypothesis. However, the limitations of mouse models are becoming alarmingly clear (Phinney et al., 2003; Radde et al., 2008). Most mouse models expressing fAD mutant APP/PS1 develop plaques and exhibit memory deficits from anywhere 2–3 months until 18–20 months of age and none of these transgenic models display tau tangle pathology or neurodegeneration, two hallmark features of human AD. However, it should be noted that transgenic mice can be ‘pushed’ to display tau tangles or neurodegeneration by subjecting them to additional manipulations such as deleting p73 gene (Wetzel et al., 2008) or simultaneously expressing multiple APP and PS1 mutations as in the case of 5xFAD transgenic mice (Oakley et al., 2006). Neurodegeneration observed in 5xFAD mice can be prevented by crossing with BACE1 knock-out animals indicating that BACE processing of APP is essential for the deleterious effects (Ohno et al., 2007). Nonetheless, the observation that most ‘straight forward’ mouse models of AD do not show tau pathology or neurodegeneration has led many in the field to classify these transgenic mice as models of amyloidopathy, rather than AD per se. Also, the rate of plaque deposition as well as the deficits in memory paradigms (Wolfer et al., 1998) are critically dependent on the mouse strain, and show tremendous strain-to-strain variation (Brown and Wong, 2007; Crabbe et al., 1999; Wahlsten et al., 2003). Finally, therapeutic strategies, such as immunization (Morgan et al., 2000) or NSAID treatment (McGeer, 2000), that showed positive effects in mouse models failed to do so in human trials. Thus, although mouse models of AD may have added to our knowledge of amyloidopathy and helped identifying factors that promote plaque formation, their limitations in capturing the essence of AD or producing a successful drug are becoming increasingly evident.

Not throwing the baby out with the bathwater

The debate regarding the exact cause of AD has been ongoing, and is likely to continue for the foreseeable future till an effective therapeutic strategy has been achieved. At one end of the spectrum are those who harbor no doubts that Aβ, in a yet undefined form, is the cause of AD and, therefore, eliminating this pathogenic Aβ will be the ultimate cure for AD. At the other end of the spectrum are those who consider Aβ to be an inconsequential bystander (or, worse, a beneficial mediator of cellular response), and believe the amyloid hypothesis to be completely wrong (Lee et al., 2007). Because of the enormous amount of data in the literature, it is easy to seek support for either view by selectively focusing on the data favorable to one’s view and ignoring the studies that runs contrary to it. From the discussion above, it should become clear that although the amyloid hypothesis remains the best defined and more widely accepted view, the evidence that Aβ causes the disease is not as strong as the proponents would like to believe. Similarly, those who believe the amyloid hypothesis to be completely wrong do not have data to support such a claim.

Since both views are unsatisfactory and are partially inconsistent with the available data, it may be helpful to reassess the hypothesis anew. The classical view of the amyloid cascade hypothesis (Fig 3A) proposes Aβ as the starting point of the cascade. Other deleterious events found in AD, such as hyperphosphorylation of tau, neuroinflammation, neurodegeneration, synapse loss, etc., lie downstream of Aβ. Over time, these deleterious events contribute to synaptic dysfunction, and ultimately cause AD. Thus, blocking the events at the Aβ level itself will prevent the downstream harmful events and prevent AD. However, a review of the literature supports a view that Aβ, instead of acting upstream of the deleterious events, exerts its effects at the same level as the other events that can also be caused by non-Aβ factors (Fig 3B). The view that there is no single primary factor that causes the disease, and that non-Aβ factors also contribute to AD as well as Aβ does, is more consistent with the present data. The concept that Aβ is only one of the factors that cause AD, explains the less than perfect correlation between Aβ and the disease severity, and may explain the recent findings why Aβ-targeted therapies are not effective against AD. An intriguing possibility (suggested by an anonymous reviewer) that the toxic form of Aβ creates a self-sustaining loop of deleterious events could also explain why Aβ-targeted therapies at the advanced stages of AD are not particularly effective. The preliminary findings reported at the 2008 ICAD meeting that multiple tau-targeted therapies (Rember, AL-108), are more effective in combating AD may be the harbinger of the idea that, perhaps, an effective therapeutic strategy can only be achieved by going beyond the amyloid hypothesis (Gong and Iqbal, 2008).

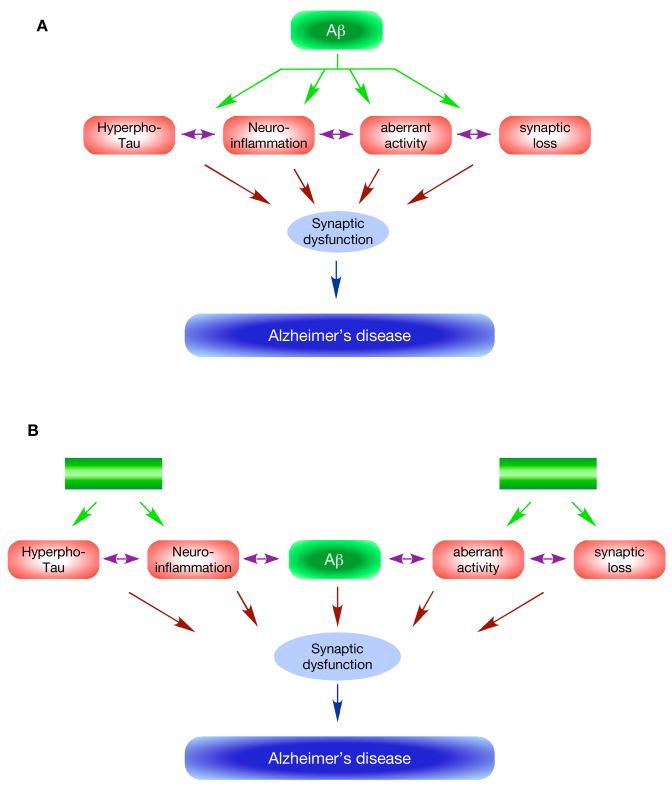

Figure 3. Reassessing the amyloid hypothesis.

The classical view (A) of the amyloid hypothesis posits that Aβ is the primary cause of AD and occupies the top position in the cascade (green oval). Increased production or decreased degradation results in accumulation of Aβ, which in a yet uncertain pathogenic form (see Figure 1) triggers a number of downstream deleterious events (purple ovals). These events are caused by Aβ as a primary effect (green arrows) and/or as a secondary effect (double-headed purple arrows). A cumulative effect of these events over time results in synaptic dysfunction, and causes AD. A distinguishing feature of this view is that Aβ acts upstream of all other events, and blocking its effects will prevent all downstream events and prevent AD. A modified view (B), which is more consistent with the presently available data, suggests that the deleterious events leading to AD are caused by Aβ as well as non-Aβ factors (green boxes). One prediction of this model is that blocking the Aβ effects will be effective only in a limited number of cases, as has been observed in the recent drug trial.

Conclusions and Perspectives

The amyloid hypothesis and the notion that Aβ is the critical primary factor in disease causation have long dominated the AD research area. However, there is growing realization that the role of Aβ in AD pathogenesis may be more limited than previously thought. The changing view is more consistent with both sets of observations- those that are supportive of the amyloid hypothesis as well as those that run against it. The notion that Aβ plays no role in AD is just as likely to be wrong as the belief that Aβ is the prime or sole cause of AD. The concept that Aβ, even if most visible, is only one of the factors that contributes to AD is likely to give a more accurate, albeit complex, picture of AD pathogenesis, and yield more comprehensive therapeutic strategies against AD.

Finally, a note on the continuing debate regarding ‘to what degree the amyloid hypothesis is right or wrong’. The proponents on both sides of this debate seem to hold strong and passionate views and are unlikely to change their minds based on the reasoning put forward here. Ultimately, the availability of an effective therapy against AD, which is the goal of both the proponents as well the critiques, will prove or disprove the amyloid hypothesis. Meanwhile, the school of thought that does not accommodate the contradictory evidence will only become less and less relevant to the field of AD.

Acknowledgments

My sincere thanks to the anonymous reviewers for bringing to my notice relevant studies and suggesting the idea that Aβ could lead to Aβ-independent events at a later stage of the disease. Many thanks to Drs. Chris Nelson and Kaushik Ghosal for reading the manuscript and vastly improving the final version. The author’s work was supported by grants from the NIH (R01AG26146), Alzheimer’s Association and CART Funds.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Baki L, Neve RL, Shao Z, Shioi J, Georgakopoulos A, Robakis NK. Wild-type but not FAD mutant presenilin-1 prevents neuronal degeneration by promoting phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase neuroprotective signaling. J Neurosci. 2008;28:483–490. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4067-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baki L, Shioi J, Wen P, Shao Z, Schwarzman A, Gama-Sosa M, Neve R, Robakis NK. PS1 activates PI3K thus inhibiting GSK-3 activity and tau overphosphorylation: effects of FAD mutations. EMBO J. 2004;23:2586–2596. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballatore C, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. Tau-mediated neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:663–672. doi: 10.1038/nrn2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentahir M, Nyabi O, Verhamme J, Tolia A, Horre K, Wiltfang J, Esselmann H, De Strooper B. Presenilin clinical mutations can affect gamma-secretase activity by different mechanisms. J Neurochem. 2006;96:732–742. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitan G, Fradinger EA, Spring SM, Teplow DB. Neurotoxic protein oligomers--what you see is not always what you get. Amyloid. 2005;12:88–95. doi: 10.1080/13506120500106958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitan G, Vollers SS, Teplow DB. Elucidation of primary structure elements controlling early amyloid beta-protein oligomerization. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:34882–34889. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300825200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Braak E. Evolution of neuronal changes in the course of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neural Transm Suppl. 1998;53:127–140. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6467-9_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RE, Wong AA. The influence of visual ability on learning and memory performance in 13 strains of mice. Learn Mem. 2007;14:134–144. doi: 10.1101/lm.473907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, Sudhof TC. A transcriptionally [correction of transcriptively] active complex of APP with Fe65 and histone acetyltransferase Tip60. Science (New York, NY. 2001;293:115–120. doi: 10.1126/science.1058783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano SM, Dodson EC, Henze DA, Joyce JG, Krafft GA, Kinney GG. The role of amyloid-beta derived diffusible ligands (ADDLs) in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Top Med Chem. 2006;6:597–608. doi: 10.2174/156802606776743066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caughey B, Lansbury PT. Protofibrils, pores, fibrils, and neurodegeneration: separating the responsible protein aggregates from the innocent bystanders. Annual review of neuroscience. 2003;26:267–298. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.26.010302.081142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng IH, Scearce-Levie K, Legleiter J, Palop JJ, Gerstein H, Bien-Ly N, Puolivali J, Lesne S, Ashe KH, Muchowski PJ, Mucke L. Accelerating amyloid-beta fibrillization reduces oligomer levels and functional deficits in Alzheimer disease mouse models. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:23818–23828. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701078200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabbe JC, Wahlsten D, Dudek BC. Genetics of mouse behavior: interactions with laboratory environment. Science (New York, NY. 1999;284:1670–1672. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5420.1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crouch PJ, Harding SM, White AR, Camakaris J, Bush AI, Masters CL. Mechanisms of A beta mediated neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:181–198. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruts M, Van Broeckhoven C. Presenilin mutations in Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Mutat. 1998;11:183–190. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1998)11:3<183::AID-HUMU1>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings BJ, Pike CJ, Shankle R, Cotman CW. Beta-amyloid deposition and other measures of neuropathology predict cognitive status in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1996;17:921–933. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(96)00170-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Strooper B. Aph-1, Pen-2, and Nicastrin with Presenilin generate an active gamma-Secretase complex. Neuron. 2003;38:9–12. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00205-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Strooper B. Loss-of-function presenilin mutations in Alzheimer disease. Talking Point on the role of presenilin mutations in Alzheimer disease. EMBO Rep. 2007;8:141–146. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande A, Mina E, Glabe C, Busciglio J. Different conformations of amyloid beta induce neurotoxicity by distinct mechanisms in human cortical neurons. J Neurosci. 2006;26:6011–6018. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1189-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du P, Wood KM, Rosner MH, Cunningham D, Tate B, Geoghegan KF. Dominance of amyloid precursor protein sequence over host cell secretases in determining beta-amyloid profiles studies of interspecies variation and drug action by internally standardized immunoprecipitation/mass spectrometry. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;320:1144–1152. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.114561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan V, Gorostiza OF, Banwait S, Ataie M, Logvinova AV, Sitaraman S, Carlson E, Sagi SA, Chevallier N, Jin K, et al. Reversal of Alzheimer’s-like pathology and behavior in human APP transgenic mice by mutation of Asp664. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:7130–7135. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509695103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Pimplikar SW. The gamma -secretase-cleaved C-terminal fragment of amyloid precursor protein mediates signaling to the nucleus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:14979–14984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261463298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gellermann GP, Byrnes H, Striebinger A, Ullrich K, Mueller R, Hillen H, Barghorn S. Abeta-globulomers are formed independently of the fibril pathway. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;30:212–220. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannakopoulos P, Herrmann FR, Bussiere T, Bouras C, Kovari E, Perl DP, Morrison JH, Gold G, Hof PR. Tangle and neuron numbers, but not amyloid load, predict cognitive status in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 2003;60:1495–1500. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000063311.58879.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glabe CC. Amyloid accumulation and pathogensis of Alzheimer’s disease: significance of monomeric, oligomeric and fibrillar Abeta. Subcell Biochem. 2005;38:167–177. doi: 10.1007/0-387-23226-5_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenner GG, Wong CW. Alzheimer’s disease and Down’s syndrome: sharing of a unique cerebrovascular amyloid fibril protein. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 1984a;122:1131–1135. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(84)91209-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenner GG, Wong CW. Alzheimer’s disease: initial report of the purification and characterization of a novel cerebrovascular amyloid protein. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 1984b;120:885–890. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(84)80190-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong CX, Iqbal K. Hyperphosphorylation of microtubule-associated protein tau: a promising therapeutic target for Alzheimer disease. Curr Med Chem. 2008;15:2321–2328. doi: 10.2174/092986708785909111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosche KM, Mortimer JA, Smith CD, Markesbery WR, Snowdon DA. Hippocampal volume as an index of Alzheimer neuropathology: findings from the Nun Study. Neurology. 2002;58:1476–1482. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.10.1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouras GK, Tsai J, Naslund J, Vincent B, Edgar M, Checler F, Greenfield JP, Haroutunian V, Buxbaum JD, Xu H, et al. Intraneuronal Abeta42 accumulation in human brain. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:15–20. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64700-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy J. Putting presenilins centre stage. Introduction to the Talking Point on the role of presenilin mutations in Alzheimer disease. EMBO Rep. 2007;8:134–135. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science (New York, NY. 2002;297:353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy JA, Higgins GA. Alzheimer’s disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science (New York, NY. 1992;256:184–185. doi: 10.1126/science.1566067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes C, Boche D, Wilkinson D, Yadegarfar G, Hopkins V, Bayer A, Jones RW, Bullock R, Love S, Neal JW, et al. Long-term effects of Abeta42 immunisation in Alzheimer’s disease: follow-up of a randomised, placebo-controlled phase I trial. Lancet. 2008;372:216–223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshi M, Sato M, Matsumoto S, Noguchi A, Yasutake K, Yoshida N, Sato K. Spherical aggregates of beta-amyloid (amylospheroid) show high neurotoxicity and activate tau protein kinase I/glycogen synthase kinase-3beta. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:6370–6375. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1237107100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephs KA, Whitwell JL, Ahmed Z, Shiung MM, Weigand SD, Knopman DS, Boeve BF, Parisi JE, Petersen RC, Dickson DW, Jack CR., Jr Beta-amyloid burden is not associated with rates of brain atrophy. Annals of neurology. 2008;63:204–212. doi: 10.1002/ana.21223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallhoff-Munoz V, Hu L, Chen X, Pautler RG, Zheng H. Genetic dissection of gamma-secretase-dependent and -independent functions of presenilin in regulating neuronal cell cycle and cell death. J Neurosci. 2008;28:11421–11431. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2873-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J, Lemaire HG, Unterbeck A, Salbaum JM, Masters CL, Grzeschik KH, Multhaup G, Beyreuther K, Muller-Hill B. The precursor of Alzheimer’s disease amyloid A4 protein resembles a cell-surface receptor. Nature. 1987;325:733–736. doi: 10.1038/325733a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein WL. Abeta toxicity in Alzheimer’s disease: globular oligomers (ADDLs) as new vaccine and drug targets. Neurochem Int. 2002;41:345–352. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(02)00050-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein WL, Krafft GA, Finch CE. Targeting small Abeta oligomers: the solution to an Alzheimer’s disease conundrum? Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:219–224. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01749-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knobloch M, Konietzko U, Krebs DC, Nitsch RM. Intracellular Abeta and cognitive deficits precede beta-amyloid deposition in transgenic arcAbeta mice. Neurobiol Aging. 2007;28:1297–1306. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFerla FM, Green KN, Oddo S. Intracellular amyloid-beta in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:499–509. doi: 10.1038/nrn2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HG, Zhu X, Castellani RJ, Nunomura A, Perry G, Smith MA. Amyloid-beta in Alzheimer disease: the null versus the alternate hypotheses. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;321:823–829. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.114009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leissring MA, Murphy MP, Mead TR, Akbari Y, Sugarman MC, Jannatipour M, Anliker B, Muller U, Saftig P, De Strooper B, et al. A physiologic signaling role for the gamma -secretase-derived intracellular fragment of APP. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99:4697–4702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.072033799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesne S, Koh MT, Kotilinek L, Kayed R, Glabe CG, Yang A, Gallagher M, Ashe KH. A specific amyloid-beta protein assembly in the brain impairs memory. Nature. 2006;440:352–357. doi: 10.1038/nature04533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesne S, Kotilinek L, Ashe KH. Plaque-bearing mice with reduced levels of oligomeric amyloid-beta assemblies have intact memory function. Neuroscience. 2008;151:745–749. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.10.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma QH, Futagawa T, Yang WL, Jiang XD, Zeng L, Takeda Y, Xu RX, Bagnard D, Schachner M, Furley AJ, et al. A TAG1-APP signalling pathway through Fe65 negatively modulates neurogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:283–294. doi: 10.1038/ncb1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masters CL, Simms G, Weinman NA, Multhaup G, McDonald BL, Beyreuther K. Amyloid plaque core protein in Alzheimer disease and Down syndrome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1985;82:4245–4249. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.12.4245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGeer PL. Cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors: rationale and therapeutic potential for Alzheimer’s disease. Drugs Aging. 2000;17:1–11. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200017010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Luehmann M, Spires-Jones TL, Prada C, Garcia-Alloza M, de Calignon A, Rozkalne A, Koenigsknecht-Talboo J, Holtzman DM, Bacskai BJ, Hyman BT. Rapid appearance and local toxicity of amyloid-beta plaques in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2008;451:720–724. doi: 10.1038/nature06616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan D, Diamond DM, Gottschall PE, Ugen KE, Dickey C, Hardy J, Duff K, Jantzen P, DiCarlo G, Wilcock D, et al. A beta peptide vaccination prevents memory loss in an animal model of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2000;408:982–985. doi: 10.1038/35050116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neve RL. Alzheimer’s disease sends the wrong signals--a perspective. Amyloid. 2008;15:1–4. doi: 10.1080/13506120701814608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordberg A. Amyloid plaque imaging in vivo: current achievement and future prospects. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging . 2008;35(Suppl 1):S46–50. doi: 10.1007/s00259-007-0700-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakley H, Cole SL, Logan S, Maus E, Shao P, Craft J, Guillozet-Bongaarts A, Ohno M, Disterhoft J, Van Eldik L, et al. Intraneuronal beta-amyloid aggregates, neurodegeneration, and neuron loss in transgenic mice with five familial Alzheimer’s disease mutations: potential factors in amyloid plaque formation. J Neurosci. 2006;26:10129–10140. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1202-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno M, Cole SL, Yasvoina M, Zhao J, Citron M, Berry R, Disterhoft JF, Vassar R. BACE1 gene deletion prevents neuron loss and memory deficits in 5XFAD APP/PS1 transgenic mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2007;26:134–145. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen MJ, James LA, Hardy JA, Williamson R, Goate AM. Physical mapping around the Alzheimer disease locus on the proximal long arm of chromosome 21. Am J Hum Genet. 1990;46:316–322. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney AL, Horne P, Yang J, Janus C, Bergeron C, Westaway D. Mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease: the long and filamentous road. Neurol Res. 2003;25:590–600. doi: 10.1179/016164103101202020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price DL, Sisodia SS. Mutant genes in familial Alzheimer’s disease and transgenic models. Annual review of neuroscience. 1998;21:479–505. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.21.1.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price DL, Tanzi RE, Borchelt DR, Sisodia SS. Alzheimer’s disease: genetic studies and transgenic models. Annual review of genetics. 1998;32:461–493. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.32.1.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radde R, Duma C, Goedert M, Jucker M. The value of incomplete mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging . 2008;35(Suppl 1):S70–74. doi: 10.1007/s00259-007-0704-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahimi F, Shanmugam A, Bitan G. Structure-function relationships of pre-fibrillar protein assemblies in Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2008;5:319–341. doi: 10.2174/156720508784533358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rovelet-Lecrux A, Hannequin D, Raux G, Le Meur N, Laquerriere A, Vital A, Dumanchin C, Feuillette S, Brice A, Vercelletto M, et al. APP locus duplication causes autosomal dominant early-onset Alzheimer disease with cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Nat Genet. 2006;38:24–26. doi: 10.1038/ng1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roychaudhuri R, Yang M, Hoshi MM, Teplow DB. Amyloid beta -protein assembly and Alzheimer’s disease. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008 doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800036200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan KA, Pimplikar SW. Activation of GSK-3 and phosphorylation of CRMP2 in transgenic mice expressing APP intracellular domain. The Journal of cell biology. 2005;171:327–335. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200505078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe DJ. The molecular pathology of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. 1991;6:487–498. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe DJ, Wolfe MS. Presenilin: running with scissors in the membrane. Cell. 2007;131:215–221. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar GM, Li S, Mehta TH, Garcia-Munoz A, Shepardson NE, Smith I, Brett FM, Farrell MA, Rowan MJ, Lemere CA, et al. Amyloid-beta protein dimers isolated directly from Alzheimer’s brains impair synaptic plasticity and memory. Nat Med. 2008;14:837–842. doi: 10.1038/nm1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J, Kelleher RJ., 3rd The presenilin hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: evidence for a loss-of-function pathogenic mechanism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:403–409. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608332104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shioi J, Georgakopoulos A, Mehta P, Kouchi Z, Litterst CM, Baki L, Robakis NK. FAD mutants unable to increase neurotoxic Abeta 42 suggest that mutation effects on neurodegeneration may be independent of effects on Abeta. J Neurochem. 2007;101:674–681. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleegers K, Brouwers N, Gijselinck I, Theuns J, Goossens D, Wauters J, Del-Favero J, Cruts M, van Duijn CM, Van Broeckhoven C. APP duplication is sufficient to cause early onset Alzheimer’s dementia with cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Brain. 2006;129:2977–2983. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki N, Cheung TT, Cai XD, Odaka A, Otvos L, Jr, Eckman C, Golde TE, Younkin SG. An increased percentage of long amyloid beta protein secreted by familial amyloid beta protein precursor (beta APP717) mutants. Science (New York, NY. 1994;264:1336–1340. doi: 10.1126/science.8191290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teplow DB, Lazo ND, Bitan G, Bernstein S, Wyttenbach T, Bowers MT, Baumketner A, Shea JE, Urbanc B, Cruz L, et al. Elucidating amyloid beta-protein folding and assembly: A multidisciplinary approach. Acc Chem Res. 2006;39:635–645. doi: 10.1021/ar050063s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry RD, Masliah E, Salmon DP, Butters N, DeTeresa R, Hill R, Hansen LA, Katzman R. Physical basis of cognitive alterations in Alzheimer’s disease: synapse loss is the major correlate of cognitive impairment. Annals of neurology. 1991;30:572–580. doi: 10.1002/ana.410300410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend M, Shankar GM, Mehta T, Walsh DM, Selkoe DJ. Effects of secreted oligomers of amyloid beta-protein on hippocampal synaptic plasticity: a potent role for trimers. J Physiol. 2006;572:477–492. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.103754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbanc B, Cruz L, Yun S, Buldyrev SV, Bitan G, Teplow DB, Stanley HE. In silico study of amyloid beta-protein folding and oligomerization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:17345–17350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408153101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Broeck B, Van Broeckhoven C, Kumar-Singh S. Current insights into molecular mechanisms of Alzheimer disease and their implications for therapeutic approaches. Neurodegener Dis. 2007;4:349–365. doi: 10.1159/000105156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villemagne VL, Fodero-Tavoletti MT, Pike KE, Cappai R, Masters CL, Rowe CC. The ART of loss: Abeta imaging in the evaluation of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. Mol Neurobiol. 2008;38:1–15. doi: 10.1007/s12035-008-8019-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahlsten D, Metten P, Phillips TJ, Boehm SL, 2nd, Burkhart-Kasch S, Dorow J, Doerksen S, Downing C, Fogarty J, Rodd-Henricks K, et al. Different data from different labs: lessons from studies of gene-environment interaction. J Neurobiol. 2003;54:283–311. doi: 10.1002/neu.10173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakabayashi T, De Strooper B. Presenilins: members of the gamma-secretase quartets, but part-time soloists too. Physiology (Bethesda) 2008;23:194–204. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00009.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh DM, Klyubin I, Shankar GM, Townsend M, Fadeeva JV, Betts V, Podlisny MB, Cleary JP, Ashe KH, Rowan MJ, Selkoe DJ. The role of cell-derived oligomers of Abeta in Alzheimer’s disease and avenues for therapeutic intervention. Biochem Soc Trans. 2005;33:1087–1090. doi: 10.1042/BST20051087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh DM, Selkoe DJ. Deciphering the molecular basis of memory failure in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. 2004;44:181–193. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh DM, Selkoe DJ. A beta oligomers - a decade of discovery. J Neurochem. 2007;101:1172–1184. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetzel MK, Naska S, Laliberte CL, Rymar VV, Fujitani M, Biernaskie JA, Cole CJ, Lerch JP, Spring S, Wang SH, et al. p73 regulates neurodegeneration and phospho-tau accumulation during aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. 2008;59:708–721. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe MS. When loss is gain: reduced presenilin proteolytic function leads to increased Abeta42/Abeta40. Talking Point on the role of presenilin mutations in Alzheimer disease. EMBO Rep. 2007;8:136–140. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfer DP, Stagljar-Bozicevic M, Errington ML, Lipp HP. Spatial Memory and Learning in Transgenic Mice: Fact or Artifact? News Physiol Sci. 1998;13:118–123. doi: 10.1152/physiologyonline.1998.13.3.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yankner BA, Lu T. Amyloid beta -protein toxicity and the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008 doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800018200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Younkin SG. Evidence that A beta 42 is the real culprit in Alzheimer’s disease. Annals of neurology. 1995;37:287–288. doi: 10.1002/ana.410370303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YW, Wang R, Liu Q, Zhang H, Liao FF, Xu H. Presenilin/gamma-secretase-dependent processing of beta-amyloid precursor protein regulates EGF receptor expression. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:10613–10618. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703903104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]