Vascular engineering remains a key thrust in advancing the field of tissue engineering of highly vascularized, complex, metabolic organs. A wide variety of strategies have been employed to control the formation of organized vascular structures in vitro and in vivo. Some of these methods include, but are not limited to, controlled growth factor delivery,[1] filamentous scaffold geometry,[2] protein micropatterning,[3] and enhanced scaffold biomaterials.[4] Many of these approaches are motivated by biomimicry of the in vivo microenvironment. Extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, both in vitro and in vivo, provide mammalian cells with biophysical cues including specific surface chemistry and rich three-dimensional surface topography[5] with features on the nanometer length scale.[6] ECM substrates provide chemical and physical external cues that dictate a variety of cell responses. Therefore, it is not only the milieu of soluble, diffusible factors, but also the adhesive, mechanical interactions with scaffolding materials, both natural and synthetic, that control select cell functions including cell attachment, migration, proliferation, differentiation, and regulation of genes.[7–9] We hypothesized that physical features on nanofabricated substrates could promote the organization of endothelial cell lineages into well-defined vascular structures in vitro by inducing the contact guidance phenomenon, which is known to affect the morphology of endothelial cells.[10–12]We found that endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) responded to ridge-groove grating of 1200 nm in period and 600 nm in depth through alignment, elongation, reduced proliferation, and enhanced migration. Although endothelial- specific markers were not significantly altered, EPCs cultured on substrate nanotopography formed supercellular band structures after 6 d. Furthermore, an in vitro Matrigel assay led to enhanced capillary tube formation and organization.

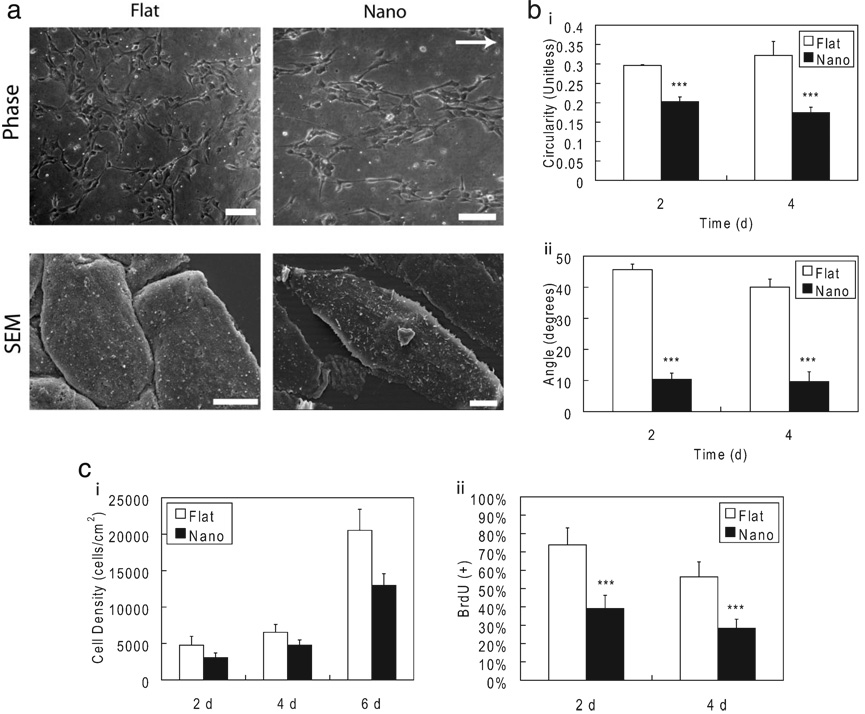

Feature geometry and dimensions of nanotopographic PDMS substrates were verified by scanning electron microscopy (SEM; Supporting Information Fig. 1). The 600 nm width for ridge and groove features was chosen to promote optimal contact guidance effects in EPCs by minimizing feature masking from the collagen coating and maximizing cell alignment through sub-micrometer features.[10,13,14] The EPCs seeded as individual cells on nanotopographic substrates and responded to linear nanotopography by alteration in morphology as observed by increased alignment and elongation (Fig. 1). These alterations were quantified by reduced average angle of alignment and circularity at 2 and 4 d. SEM imaging confirms that the EPCs were aligned an elongated in direction of substrate features. Furthermore, the morphological alterations were maintained throughout long-term culture on nanotopographic substrates for up to 6 d. EPCs cultured on nanotopographic substrates also exhibited reduced proliferation as measured by BrdU assay (Fig. 1, Supporting Information Fig. 2) and reduced cell growth kinetics as determined by cell density compared to EPCs cultured on flat substrates. The observed doubling time was (16.2 ± 0.8) to (20.9 ± 1.9) h for cells grown on flat and nanotopographic substrates, respectively. A third component of the contact guidance response that was observed in EPCs was enhanced migration. EPCs on nanotopographic substrates exhibited a higher overall migration velocity as well as enhanced directed migration, as measured by effective migration distance (Experimental). The average velocity of EPCs on nanotopographic and flat substrates was (0.80 ± 0.45) and (0.54 ± 0.27) µm min−1 (*** p < 0.001), respectively, while the effective displacement due to migration was (23.6 ± 12.1) and (15.6 ± 10.1) lm (*** p < 0.001), respectively (Supporting Information Fig 3).

Figure 1.

EPCs respond to substrate nanotopography. a) EPCs cultured on nanotopography exhibited morphological alterations when cultured on substrates with topographical features at 2 d. EPCs are aligned and elongated as measured by b) reduced circularity (*** p < 0.001) and reduced average angle of the major axis (*** p < 0.001) at 2 and 4 d. These morphological changes were observed after 4 h and stable throughout 6 d as well. c) Substrate nanotopography also reduces the proliferation of EPCs. Growth rates were reduced in EPCs cultured on nanotopography when compared to those cultured on flat surfaces. The doubling time was increased from 16.2 to 20.9 h. The reduced proliferation was verified by reduced frequency of cells in S-phase as determined by a BrdU incorporation assay at 2 and 4 d (*** p < 0.001). The direction of the linear nanotopographic features is indicated by the arrow. Scale bars in (a-phase) and (a-SEM) are 100 and 5 µm, respectively.

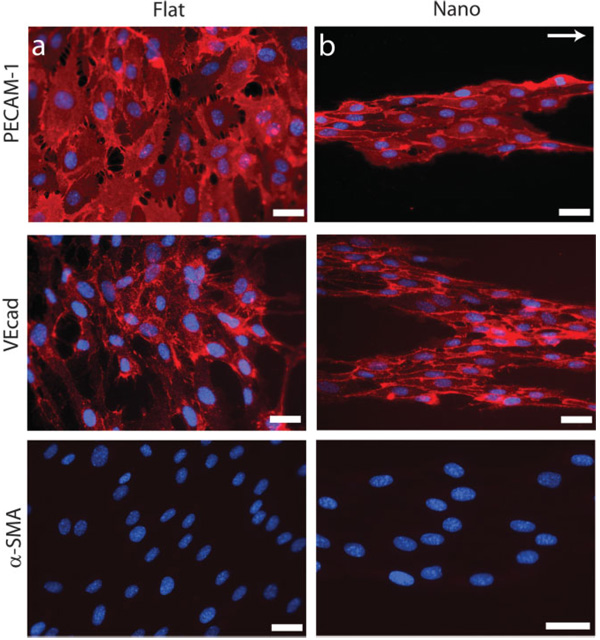

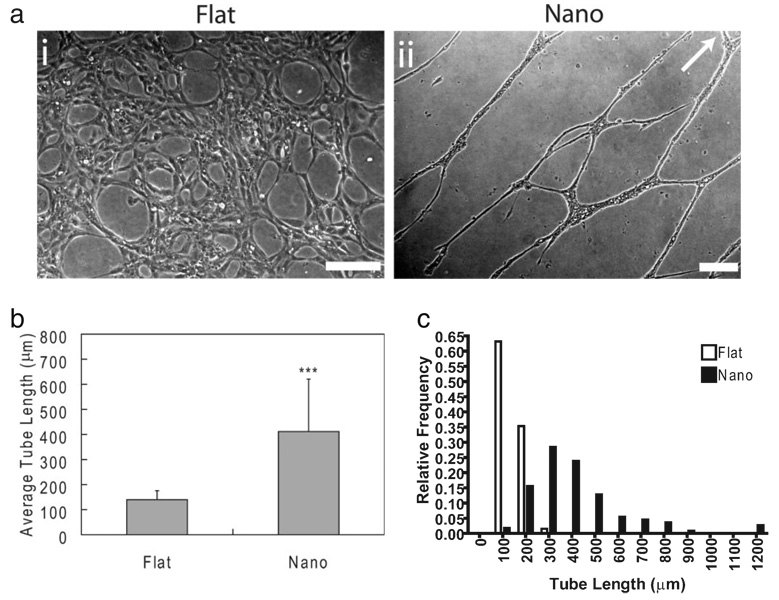

Linear nanotopographic substrates organized populations of EPCs into band structures at 6 d consisting of hundreds of cells and extending for millimeters in length. The supercellular bands contained a well-defined edge that paralleled the feature grating. This edge was identified by EPCs with highly elongated, constrained morphology. These bandlike structures were distinct from each other and did not merge to form confluent monolayers of cells. These gross morphological changes were observed for up to 6 d. The morphology of EPCs cultured on nanotopography lies in stark contrast to EPCs cultured on flat substrates, which did not form supercellular structures and instead produced confluent monolayers of EPCs after 6 d. Despite the marked alterations in morphology, proliferation, and migration states, the level of proteinlevel expression of selected markers was observed to be similar across substrates, as assessed by immunohistochemistry at 6 d. These markers included CD31 (platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule-I; PECAM-1), vascular endothelial cadherin (VEcad), and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA, negative staining; Fig. 2). Additional markers that were similarly expressed in cells cultured on both substrates include von Willebrand factor, vascular endothelial growth factor-2 (VEGF-2; KDR), and lectin receptor (Supporting Information Fig. 4). The effects of nanotopography on morphology and endothelial-cell specific marker expression were observed to be independent. The addition of Matrigel induced capillary tube formation in EPCs cultured on both substrates in less than 4 h as assessed by light microscopy. EPCs cultured on flat substrates formed short, randomly oriented capillaries while EPCs cultured on nanotopography formed well-defined capillary tubes with increased length (Fig. 3). Furthermore, capillary tubes on nanotopographic substrates exhibited enhanced alignment and organization. The fraction of EPCs recruited into capillary tubes was also increased dramatically in cultures with substrate nanotopography. This observation contrasted with the observed tube formation in EPCs culture on flat substrates, which was characterized by a high density of tubes with short lengths oriented in random directions. Furthermore, only a small fraction of cells cultured on flat substrates participated in capillary tube formation. Although the three-dimensional morphology of cells was not explicitly studied in this work, others have shown that the culture of endothelial cells in the presence of Matrigel induces the formation of three-dimensional capillary tubes with lumens.[15,16]

Figure 2.

Nanotopography induces the formation of supercellular band structures in long-term EPC culture. EPCs cultured on flat substrates simply began forming confluent layers of cells after 6 d of culture. This lies in stark contrast to EPCs cultured on nanotopography, which did not form confluent layers of cells. Rather, EPCs began to form supercellular band structures aligned in the direction of the features after 6 d of culture. These morphological differences are evident through staining of PECAM-1 and VEcad. The absence of α-SMA suggests that these cells maintain their endothelial cell phenotype. The protein-level expression of these endothelial-specific markers is similar in cells cultured on both nanotopographic and flat substrates. The direction of the linear nanotopographic features is indicated by the arrow. Scale bars are 50 µm.

Figure 3.

In vitro capillary tube formation assay. Capillary tube formation was induced by that addition of Matrigel after 6 d. a) EPCs cultured on flat substrates (i) formed a low density of unorganized capillary tubes while EPCs cultured on nanotopographic substrates (ii) formed extensive networks of organized structures, b,c) which had longer average lengths when compared to EPCs cultured on flat substrates (*** p < 0.001). Furthermore, the vast majority of EPCs on nanotopographic substrates were recruited into capillary tubes, which was far greater than that of EPCs on flat substrates. Image was rotated demonstrate the length of observed tubules. The direction of the linear nanotopographic features is indicated by the arrow. Scale bars are 200 µm..

The observed cell response of EPCs to linear substrate nanotopography in this study is in concert with previous work on a variety of substrate materials and cell types. Alignment of cells to linear micrometer and sub-micrometer scale features is a well-characterized response that occurs in many different cells types including endothelial cells.[10,14,17–20] Reduced proliferation has also been observed in a variety of cell types including smooth muscle cells and human embryonic stem cells.[19,21] The increased migration velocity of EPCs on substrate nanotopography is also in agreement with previous work of various mammalian cell types including corneal epithelial cells.[22] This collective response is a principle element in the in vitro contact guidance with substratum cues. One result of note regarding this aspect of EPC responses to nanotopography is that the morphological changes were maintained for long-term culture. Oftentimes the elongated morphology becomes affected as cell growth leads to impingement of protrusions. The maintenance of this morphological aspect can be attributed to the formation of aligned bands of cells which enabled preservation of the elongated morphology.

Cells have been shown to respond to substrate nanotopography at the protein level as well.[23] While it is likely that nanotopography impacts the genetic profile of EPCs, the expression profile of selected markers was similar in EPCs cultured on both substrates, which implies that surface nanotopography has no significant impact on the protein level of endothelial-specific markers. Despite this observation, the impact of nanotopography on the overall organization of EPCs and the enhanced in vitro capillary tube formation was maintained. The nanotopographic features were hypothesized to play a governing role in this observation via the enhanced formation of band structures primarily through two means. First, linear nanotopographic features align and elongate individual EPCs which ultimately form clusters of EPCs. This clustering is hypothesized to promote cell–cell interactions, which ultimately lead to the formation of the observed band structures. Second, the reduction in proliferation prevents the growth of EPCs into confluent monolayers of cells on nanotopographic substrates. The unoccupied surface area is hypothesized to enable the rapid formation of capillary tubes in vitro. Conversely, the formation of confluent layers, as observed in cells cultured on flat substrates, possibly retards the formation of capillary tubes because of the spatial constraint of EPCs interfering with each other.

The observations in this study further suggest the continued application and integration of nanotopographic features in tissue engineering systems. For example, biodegradable polymers amenable to soft-lithography could be used in future studies.[13,20,24] Furthermore, other vascular progenitor cells and co-culture systems could also be employed to explore the use of systems with physical surface cues for therapeutic applications.[25] This system could also be directly used to study the mechanisms of vascular genesis by investigating the cellular pathways involved in the observed enhanced capillary tube formation. The introduction of co-cultures could potentially serve as a platform to elucidate the underlying homotypic and heterotypic cellular processes that are biologically relevant to blood vessel formation in vitro and in vivo.[26]

Experimental

Fabrication and Preparation of Nanotopographic Substrates

100 mm silicon wafers were coated with Shipley SPR220-3 photoresist, exposed using a GCA AS200 stepper, and post-baked. Wafers were etched using a silicon inductively coupled plasma (ICP) etch process using SF6/argon in a VLR-700, plasma ashed, and cleaned for preparation in replica-molding (MEMS Exchange, Reston, VA) using poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS, Dow Sylgard 184, Essex Chemical, Clifton, NJ (Supporting Information Fig. 1). PDMS was chosen for ease of fabrication and optical clarity to facilitate characterization. Owing to the hydrophobic nature of PDMS, which typically leads to low adhesion of cells to surfaces, collagen was adsorbed onto the surface to promote adhesion and attachment of EPCs. Briefly, substrates were plasma cleaned (PDC-001, Harrick Scientific Co) for 300 s at 80 W RF power with atmospheric gas at 250 mTorr (1 Torr = 1.333 × 102 Pa). A 25 µg mL−1 solution of collagen I from rat tail in phosphate buffer solution (PBS; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was immediately adsorbed onto the surface and incubated for 3 h at 37 °C.

Human Endothelial Progenitor Cell Culture

EPCs (commercially available from NDRI, Philadelphia PA) were purified from cord blood with 99.2 % CD31+/CD45-purity according to manufacturer specifications. EPCs were grown on type I collagen-coated tissue culture polystyrene in Clonetics Endothelial Basal Medium-2 (EBM-2) (Cambrex Corporation, East Rutherford, NJ) with 0.1 % VEGF in addition to manufacturer-supplied SingleQuots growth supplements. Cells were incubated at 37 °C with 5 % CO2 and passaged every 3–4 d. EPCs were seeded onto substrates at 15000 cells per cm2 and maintained in EBM-2 medium.

Proliferation and Metabolism Studies

EPC proliferation on nanotopographic and flat substrates was studied with BrdU incorporation assays using the BrdU Staining Kit (Invitrogen Corporation). EPCs received BrdU labeling reagent (1:100) 2 d and 4 d after being plated upon patterned and flat substrates. Cells were incubated for 24 h with the reagent, then washed twice with PBS (Invitrogen Corporation) and fixed with 70 % ethanol for 20 min in 4 °C. Micrographs of cells were taken at 2 d and 4 d to examine cell density kinetics

Cell Morphology Imaging and Characterization

SEM and phase micrographs of cells taken at 10× magnification were used to characterize morphological parameters for each sample analyzed. The circularity [27–29] and alignment angle of the cell were calculated using perimeter and area measurements by using Axiovision software (Zeiss). Alignment angle was calculated by fitting an ellipse to the cell body, measuring the normalized angle between the major axis and the feature orientation. The circularity C was calculated using the following formula:

| (1) |

where A is the projected area of the cell and P is the perimeter of the cell. Circularity was used as a metric of cell elongation; average angle was used as an index cell alignment.

Scanning Electron Microscopy

Cells were fixed with Accustain formalin-free fixative (Sigma) for 20 min at room temperature, washed three times with DPBS, and post-fixed with 1 % (w/w) OsO4 in water for 20 min. A graded ethanol series was implemented for dehydration of the cells (25 %, 50 %, 75 %, and 90 % v/v ethanol in ddH2O), 5 min per step. The samples were then immersed for 10 min in 100 % ethanol followed by HMDS (Sigma), and dried for 24 h at 24 °C. Samples were sputter-coated using a Cressington 108 Auto sputter coater (Cressington Scientific Instruments Inc, Cranberry Twp, PA). Scanning electron microscopy images were taken using a Hitachi S-3500N at 5 kV to assess three-dimensional morphology.

Immunohistochemistry and Fluorescent Microscopy

EPCs were fixed with Accustain (Sigma), incubated with 0.1 % triton X-100 in PBS (v/v), and stained for cytoskeleton proteins and endothelial markers. The primary antibodies used were: anti-α smooth muscle actin (Sigma), anti-CD31 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), anti-von Willebrand Factor (Dako, Carpinteria, CA), anti-VEGF receptor-2 or KDR (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), and anti-vascular endothelial cadherin (Chemicon/Millipore, Billerica, MA). Cells were washed twice with PBS and incubated with Cyanine3 (Cy3)-conjugated secondary antibodies (Sigma) followed by fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated lectin (Sigma). Cells with anti-KDR were stained according to manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) for 2 min, mounted, and viewed using a Zeiss microscope equipped with OpenLab software. Exposure times were kept constant when comparing immunohistochemistry across substrates for each specific marker.

Cell Migration Studies

EPCs on both nanotopographic and flat substrates were imaged at 48 h. Time-lapse images were taken every 3 min for 90 min for a total of 31 images. Cell migration was quantified by manually tracking the spatial coordinates about the nucleus of 100 migrating cells using AxioVision software. Average migration velocity Vmig was calculated by the following equation:

| (2) |

The effective displacement due to migration Dmig,eff was calculated from the difference in spatial coordinates by the following equation:

| (3) |

where the initial and final coordinates are given by (x0, y0) and (xfin, yfin), respectively.

In Vitro Capillary Tube Formation Assay

Capillary tubes were formed in vitro using BD Matrigel Matrix (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Culturing cells with endothelial phenotype on Matrigel substrates has been shown to produce capillary tube structures [30–32]. After 6 d of culture on specified substrates, medium was aspirated from the cells, and 500 µL of 4 °C Matrigel was added and incubated for 60 min at 37 °C followed by the addition of 500 µL of EBM-2 medium. Capillary tube formation was assessed 24 h after Matrigel deposition using light microscopy.

Statistics

All observations of morphology and proliferation were based on three populations of n ≥ 100 for each experiment across two experiments (n = 6). Assays were performed in triplicate for each experiment (n = 3). All graphical and tabulated data displayed as mean ± S.D. Significance tests were calculated using unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-Test with unequal variance (Microsoft Excel, Redmond, WA). Significance levels were set at * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001.

Footnotes

The authors would like to acknowledge the following: Dr. Eliza Vasile from the Center for Cancer Research, Microscopy and Imaging Core Facility at MIT for assistance with imaging, the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (fellowship to S.G.), the MEMS Technology Group at the Draper Laboratory for direct funding for C.J.B. and use of facilities; funding provided through DL-H-550154; NIH grants R01-DE-013023-06, P41 EB002520-01A1 and 1R01HL076485-01A2. The content of this paper does not necessarily reflect the position or the policy of the government, and no official endorsement should be inferred. Supporting Information is available online from Wiley InterScience or from the authors.

Contributor Information

Christopher J. Bettinger, Biomedical Engineering Center, Charles Stark Draper Laboratory 555 Technology Square, Cambridge, MA 02139 (USA) Department of Materials Science and Engineering, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Room E25-342, 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02139, (USA).

Zhitong Zhang, Department of Chemical Engineering, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Room E25-342, 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02139, (USA).

Sharon Gerecht, Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, Johns Hopkins University, Maryland Hall 216, 3400 North Charles Street, Baltimore, MD, 21218 (USA).

Jeffrey T. Borenstein, Email: jborenstein@draper.com, Biomedical Engineering Center, Charles Stark Draper Laboratory, 555 Technology Square, Cambridge, MA 02139 (USA).

Robert Langer, Email: rlanger@mit.edu, Department of Chemical Engineering, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Room E25-342, 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02139, (USA).

References

- 1.Lee KY, Peters MC, Anderson KW, Mooney DJ. Nature. 2000;408:998. doi: 10.1038/35050141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gafni Y, Zilberman Y, Ophir Z, Abramovitch R, Gazit MJZ, Domb A, Gazit D. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:3021. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.3021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kobayashi A, Miyake H, Hattori H, Kuwana R, Hiruma Y, Nakahama K, Ichinose S, Ota M, Nakamura M, Takeda S, Morita I. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007;358:692. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.04.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ford MC, Bertram JP, Hynes SR, Michaud M, Li Q, Young M, Segal SS, Madri JA, Lavik EB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:2512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506020102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Timpl R. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1996;8:618. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(96)80102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abrams GA, Schaus SS, Goodman SL, Nealey PF, Murphy CJ. Cornea. 2000;19:57. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200001000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watt FM, Jordan PW, O’Neill CH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1988;85:5576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.15.5576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McBeath R, Pirone DM, Nelson CM, Bhadriraju K, Chen CS. Dev. Cell. 2004;6:483. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00075-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen CS, Tan J, Tien J. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2004;6:275. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.6.040803.140040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bettinger CJ, Orrick B, Misra A, Langer R, Borenstein JT. Biomaterials. 2006;27:2558. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uttayarat P, Lelkes PI, Composto RJ. Mat. Res. Soc. Symp. Proc. 2005;845:AA8.5.1. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uttayarat P, Toworfe GK, Dietrich F, Lelkes PI, Composto RJ. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2005;75A:668. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Owen GR, Jackson J, Chehroudi B, Burt H, Brunette DM. Biomaterials. 2005;26:7447. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teixeira AI, Abrams GA, Bertics PJ, Murphy CJ, Nealey PF. J. Cell Sci. 2003;116:1881. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levenberg S, Golub JS, Amit M, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Langer R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:4391. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032074999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCloskey KE, Gilroy ME, Nerem RM. Tissue Eng. 2005;11:497. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foley JD, Grunwald EW, Nealey PF, Murphy CJ. Biomaterials. 2005;26:3639. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jungbauer S, Kemkemer R, Gruler H, Kaufmann D, Spatz JP. ChemPhysChem. 2004;5:85. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200300868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gerecht S, Bettinger CJ, Zhang Z, Borenstein J, Vunjak-Novakovic G, Langera R. Biomaterials. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.05.027. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walboomers XF, Croes H, Gensel LA, Jansen JA. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1999;47:204. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199911)47:2<204::aid-jbm10>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yim EKF, Reano RM, Pang SW, Yee AF, Chen CS, Leong KW. Biomaterials. 2005;26:5405. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.01.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diehl KA, Foley JD, Nealey PF, Murphy CJ. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2005;75A:603. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yim EKF, Pang SW, Leong KW. Exp. Cell Res. 2007;313:1820. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sarkar S, Dadhania M, Rourke P, Desai TA, Wong JY. Acta Biomater. 2005;1:93. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferreira LS, Gerecht S, Shieh HF, Watson N, Rupnick MA, Dallabrida SM, Vunjak-Novakovic G, Langer R. Circ. Res. 2007;101:286. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.150201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levenberg S, Rouwkema J, Macdonald M, Garfein ES, Kohane DS, Darland DC, Marini R, van Blitterwijk CA, Mulligan RC, D’Amore PA, Langer R. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:879. doi: 10.1038/nbt1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramires PA, Mirenghi L, Romano AR, Palumbo F, Nicolardi G. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2000;51:535. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(20000905)51:3<535::aid-jbm31>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thurston G, Jaggi B, Palcic B. Cytometry. 1988;9:411. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990090502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keresztes Z, Rouxhet PG, Remacle C, Dupont-Gillain C. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2006;76A:223. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Merchan JR, Chan B, Kale S, Schnipper LE, Sukhatme VP. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2003;95:388. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.5.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murasawa S, Llevadot J, Silver M, Isner JM, Losordo DW, Asahara T. circulation. 2002;106:1133. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000027584.85865.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lambiase PD, Edwards RJ, Anthopoulos P, Rahman S, Meng YG, Bucknall CA, Redwood SR, Pearson JD, Marber MS. circulation. 2004;109:2986. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000130639.97284.EC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]