Abstract

Histidine (His)-tag is widely used for affinity purification of recombinant proteins, but the yield and purity of expressed proteins are quite different. Little information is available about quantitative evaluation of this procedure. The objective of current study was to evaluate His-tag procedure quantitatively and to compare it with immunoprecipitation using radiolabeled tristetraprolin (TTP), a zinc finger protein with anti-inflammatory property. Human embryonic kidney 293 cells were transfected with wild-type and nine mutant plasmids with single or multiple phosphorylation site mutation(s) in His-TTP. These proteins were expressed and mainly localized in the cytosol of transfected cells by immunocytochemistry and confocal microscopy. His-TTP proteins were purified by Ni-NTA beads with imidazole elution or precipitated by TTP antibodies from transfected cells after being labeled with [32P]-orthophosphate. The results showed that 1) His-tag purification was more effective than immunoprecipitation for TTP purification; 2) mutations in TTP increased the yield of His-TTP by both purification procedures; and 3) mutations in TTP increased the binding affinity of mutant proteins for Ni-NTA beads. These findings suggest that bioengineering phosphorylation sites in proteins can increase the production of recombinant proteins.

Keywords: His-tag purification, immunoprecipitation, in vivo radiolabeling, phosphorylation site, site-directed mutagenesis, tristetraprolin, zinc finger protein

Introduction

Histidine (His)-tag affinity purification is a method of choice for the purification of a large number of recombinant proteins expressed in various overexpression systems. The popularity of this method is due in part to its many advantageous properties such as high affinity of the His-tag in the recombinant proteins with nickel-nitrilotriacetic agarose (Ni-NTA) beads and easy elution with imidazole buffer. In addition, the small size of His-tag does not interfere with biochemical activities of the tagged proteins in most cases. However, the yield and purity of various proteins purified by this procedure are quite different. Information is lacking about quantitative evaluation of this procedure.

His-tag procedure has been used to express tristetraprolin/zinc finger protein 36 (TTP/ZFP36, also called TIS11 or Nup475) in E. coli (1, 2) and human cells (3). TTP, a hyperphosphorylated mRNA binding and destabilizing protein (4), regulates inflammatory responses at the post-transcriptional level (5). TTP binds to mRNA adenylate and uridylate-rich elements (AREs) with high affinity for UUAUUUAUU nucleotides (3, 6-10). The specific binding of TTP to AREs causes destabilization of those mRNA molecules coding for proteins such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα) (3, 11-13), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (14, 15), cyclooxygenase 2 (16, 17), interleukin 2 (18), and transcription factor E47 (19). TNFα and GM-CSF mRNAs are stabilized in TTP-deficient mice (12, 14). These cytokines accumulate in TTP knockout mice and cause a severe systemic inflammatory response including arthritis, autoimmunity, and myeloid hyperplasia (20, 21). Upregulation of TTP reduces inflammatory responses in macrophages (22). These lines of evidence support the proposal that TTP is an anti-inflammatory protein (5, 23-26). TTP may play other important roles in normal physiology and disease development. TTP is a potential target for the physiological control of blood pressure (27) and for the prevention of suicidal behavior (28) and of obesity-associated metabolic disorders (29). Finally, TTP may have nutritional significance in disease prevention since TTP expression is increased by insulin (30, 31), green tea (32), and cinnamon polyphenol extract (33, 34).

The objective of this study was to evaluate His-tag procedure quantitatively and to compare it with immunoprecipitation (IP) using radiolabeled wild-type (WT) and mutant TTP proteins in transfected human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells. Our results demonstrated that His-tag purification was more effective than IP and mutations in TTP increased the yield of purified proteins by both purification procedures as well as the binding affinity of mutant proteins for Ni-NTA beads.

Materials and Methods

Protein Expression Plasmids

WT expression plasmid (pHis-TTP or CMV.(his)6.N.hTTP) contained DNA sequence for six histidine residues between the sequences for the initiator methionine and the second asparate of full-length human TTP (GenBank accession no. NP_003398) (3, 15). Plasmids were produced by site-directed mutagenesis and by recombination of various DNA fragments as described (3, 35). These mutant plasmids contained serine and thronine to alanine mutation(s) in human TTP, including S197A, S(197,228)A, S(197,218,228)A, S(214,218,228)A, S(197,214,218,228)A, S(214,218,228,296)A, S(197,214,218,228,296)A, S(88,197,214,218,228,296)A, S(88,186,197,214,218,228)A, S(88,186,197,214,218,228,296)A, S(88,197,214,218,228)T271A, S(88,197,214,218,228,296)T271A, S(88,90,93,197,214,218,228)A, and S(88,90,93,197,214,218,228,296)A (35).

Transfection of Human HEK293 Cells

HEK293 cells were transfected with pHis-TTP plasmids using the calcium phosphate precipitation method as described (3, 13). HEK293 cells (0.7 million cells/10 mL medium /10-cm dish) were grown overnight at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal calf serum (FCS), 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 2 mM L-glutamine. The medium was replaced with 9 mL fresh medium and incubated for 4 h under the same conditions. The cells were then transfected with 1 mL transfection mixture containing 0.5 mL of a DNA/calcium solution (0.5 μg of pHis-TTP plasmid, 4.5 μg of pBS+ carrier plasmid, and 250 mM CaCl2) and 0.5 mL of a HEPES/phosphate solution (50 mM HEPES, 280 mM NaCl, 2 mM NaH2PO4, and 4 mM Na2HPO4, pH 7.1). The DNA/calcium solution was added dropwise to the HEPES/phosphate solution while bubbling with a stream of nitrogen gas. The transfection mixture was incubated for 20 min at room temperature before being added to the dish (1 mL/10-cm dish).

In Vivo Phosphate Radiolabeling

HEK293 cells were washed next morning following transfection and incubated in 10 mL fresh medium under the same conditions for 24 h. The old medium was removed from the dish followed by wash twice each with 5 mL no-phosphate DMEM, pH 7.0. The dish was added with 6 mL of no-phosphate DMEM plus 1% FCS (approximately 15 μM phosphate in the medium, adjust to pH 7.0) and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 3 h. The medium was aspirate off. DMEM (4 mL without phosphate or serum) with [32P]orthophosphate (0.1 mCi/mL) was added to each dish. The dishes were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 1.5 h.

Cell Lysis

Following in vivo radiolabeling, the hot medium was aspirate off. Cells in each plate were washed three times each with 5 mL PBS and lysed directly in the plate at 4 °C for 1 h with 0.6 mL His-tag purification buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 250 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM PMSF, 1 μg/mL leupeptin, 0.5 % NP-40) plus 10 mM imidazole. The lysate was transferred into a 1.5-mL microfuge tube and saved in − 20 °C overnight. The cell lysate was thawed at 37 °C for 30 min and centrifuged at 10,000g for 10 min. The 10,000g supernatant and the pellet were stored at − 20 °C.

His-tag Purification Using Ni-NTA Beads

The 10,000g supernatant (500 μL) from soluble extracts was transferred to a 15-mL Falcon tube and mixed with 50 μL of 50% slurry of Ni-NTA beads (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The mixtures were rotated at 4 °C for 2 h and then transferred into a Cytospin column inserted in 2-mL tube followed by centrifugation at 1000g for 2 min. The beads were washed four times each with 0.25 mL wash buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaF, 0.05 % Tween-20, pH8.0) plus 20 mM imidazole by centrifugation at 1000g for 2 min. The bound proteins in the washed beads were eluted out with 50 μL of 100, 200, and 250 mM imidazole in wash buffer by centrifugation at 1000g for 2 min. The eluted proteins and the remaining beads were stored at − 20 °C. Radioactivity was counted using MicroBeta JET/1450 Microbeta Wallac Jet Liquid Scientilation and Luminescence Counter (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Gaithersburg, MD).

Immunoprecipitation Using TTP Antibodies

The 10,000g supernatant (100 μL) from soluble extracts was thawed at 37 °C for 30 min and mixed with 20 μL TTP antiserum raised against recombinant MBP-TTP (3). After incubation for 90 min at 4 °C with gentle rotation, each tube was added with 50 μL of 50% slurry of Protein A Sepharose CL-4B (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) in His-tag purification buffer plus 10 mM imidazole. This mixture was incubated for 30 min at 4 °C and centrifuged at 2,000g for 5 min. The beads were washed three times each with 0.5 mL of the above buffer. The final washed beads were suspended in 20 μL of the above buffer and 5 μL of 5X SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Radioactivity in the suspension was counted as above.

Protein Concentration Determination, SDS-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (PAGE), and Immunoblotting

Protein concentrations were determined with the Bio-Rad Dye assay kit and BSA as the standard as described (3). SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting followed described procedures (36). The primary antibodies were anti-MBP-TTP serum raised in New Zealand white rabbits against the purified MBP-TTP fusion protein, as described previously (37). The secondary antibodies were affinity-purified goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) horseradish peroxidase conjugate with human IgG absorbed (Bio-Rad Laboratory).

Immunocytochemistry and Confocal Microscopy

HEK293 cells were grown overnight on glass coverslips in tissue culture plate (Becton Dickinson and Company, Lincoln Park, NJ). The cells were transfected with pHis-TTP (50 ng DNA/1 mL/well) and incubated overnight as described above. After another 24-h incubation, the cells were proceeded to immunocytochemistry using a similar procedure as described (3) with TTP antibodies (1:5000 dilution). The slides were examined and imaged with an LSM510 UV confocal microscope (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY).

Results

Expression and Localization of WT and Mutant TTP Proteins in Transfected Human Cells

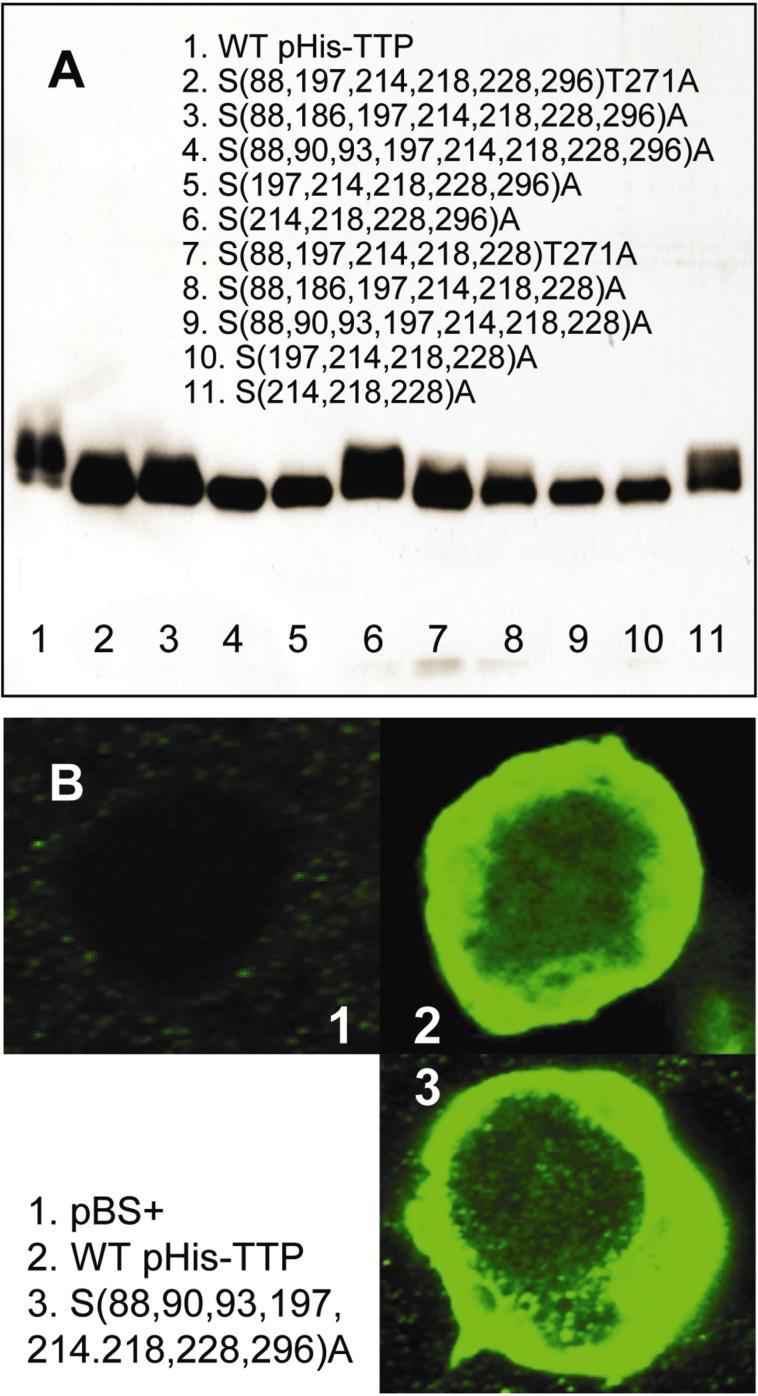

HEK293 cells were transfected with pBS+ plasmid (carrier) and pHis-TTP plasmids coding for WT and mutant TTP proteins with mutations at S(197, 218, 228), S(214,218,228), S(214,218,228,296), S(197,214,218,228), S(197,214,218,228,296), S(88,197,214,218,228,296)T271, S(88,186,197,214,218,228,296), S(88,90,93,197,214,218,228,296), S(88,197,214,218,228)T271, S(88,186,197,214,218,228), and S(88,90,93,197,214,218,228). Immunoblotting showed that all of these His-TTP proteins were expressed in the transfected cells (Figure 1A). The mutant TTP proteins migrated faster than the WT TTP protein on SDS-PAGE (Figure 1A, lane 1 vs. lanes 2−11). Some of the mutant TTP protein bands were collapsed into a sharp band(s) (Figure 1A, lanes 4, 5, 8−10).

Figure 1. Expression and localization of WT and mutant TTP proteins in HEK293 cells.

(A) Immunoblotting. HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with pHis-TTP plasmids. PBS-washed cells were lysed followed by centrifuged at 10,000g for 10 min. Soluble proteins in the supernatant (10 μg/lane) were separated by SDS-PAGE. His-TTP proteins were detected by immunoblotting with TTP antibodies. (B) Confocal microscopy. HEK293 cells were transfected with pBS+ control plasmid (1) and pHis-TTP plasmids encoding WT TTP (2) and mutant TTP with S(88, 90, 93, 197, 214, 218, 228, 296)A mutations (3). The cells were stained with TTP antibodies and labeled with goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488. Immunofluorescence was recorded by confocal microscopy.

Confocal microscopy showed that endogenous TTP was almost undetectable in HEK293 cells transfected only with the pBS+ carrier plasmid by immunostaining with TTP antibodies, since immunofluorescence intensity was extremely low in these cells (Figure 1B-1). WT TTP was overexpressed and mainly localized in the cytosol of HEK293 cells following transfection with WT pHis-TTP plasmid (Figure 1B-2). Mutant TTP proteins were also expressed and primarily localized in the cytosol of transfected HEK293 cells. Confocal microscopy showed that most of the immunofluorescence was detected in the cytosol of HEK293 cells after transfection with mutant plasmids encoding TTP proteins with S(88, 90, 93, 186, 214, 218, 228, 296)A mutations (Figure 1B-3) and other mutations (data not shown).

His-Tag Purification of WT and Mutant TTP Proteins from Radiolabeled Transfected Human Cells

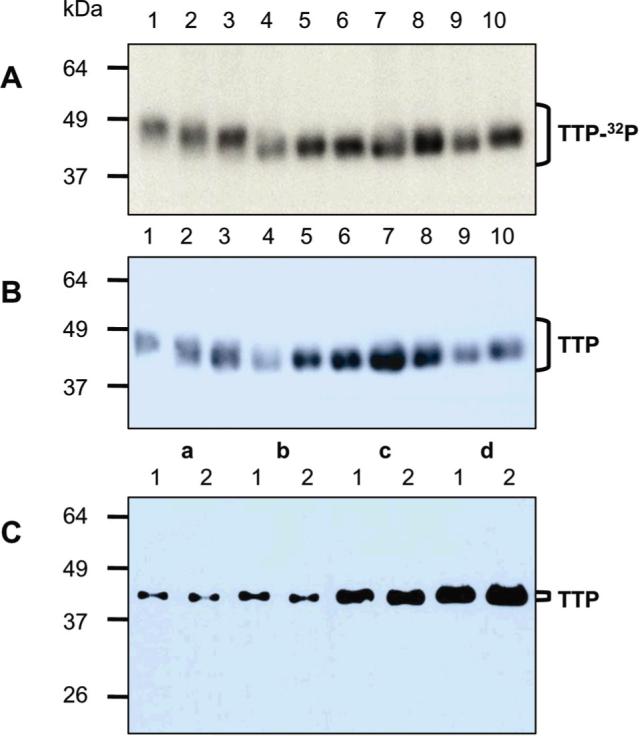

To quantify His-tag purification procedure for His-TTP proteins, radiolabeled cell extracts were used. His-TTP proteins were essentially the only proteins eluted by imidazole solution (35). Autoradiography showed that all mutant His-TTP proteins were expressed and purified by Ni-NTA procedure (Figure 2A). The protein identity was determined by immunoblotting with TTP antibodies (Figure 2B). This provided the basis for quantitative evaluation of His-tag purification procedure.

Figure 2. His-tag purification of WT and mutant TTP proteins from radiolabeled HEK293 cells.

HEK293 cells were transfected with the 10 plasmids. The cells were labeled with [32P]orthophosphate (A and B) or not labeled (C). Soluble proteins in the supernatant (A and B) were mixed with Ni-NTA beads followed by centrifugation. The pellet was washed four times with 20 mM imidazole buffer. Proteins bound to the washed beads were eluted with 100 mM imidazole buffer. Proteins (4 μL/lane) were separated by SDS-PAGE. (A) [32P]-labeled proteins were detected with autoradiography. (B) His-TTP proteins were identified with TTP antibodies. Lane 1: WT His-TTP, lane 2: His-TTP with S197A mutation, lane 3: His-TTP with S(197,228)A mutations, lane 4: His-TTP with S(197,218,228)A mutations, lane 5: His-TTP with S(197,214,218,228)A mutations, lane 6: His-TTP with S(197,214,218,228,296)A mutations, lane 7: His-TTP with S(88,197,214,218,228,296)A mutations, lane 8: His-TTP with S(88,186,197,214,218,228,296)A mutations, lane 9: His-TTP with S(88,197,214,218,228)T271A mutations, lane 10: His-TTP with S(88,90,93,197,214,218,228,296)A mutations. (C) Effect of the amounts of His-TTP proteins on their electrophoretic mobility. TTP proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and identified by immunoblotting with TTP antibodies 1: S(88,90,93,197,214,218,228,296,)A, 2: S(197,214,218,228,296)A, a: 1 μg protein in 10,000g supernatant, b: 2 μg protein in 10,000g supernatant, c: 5 μg protein in 10,000g supernatant, d: 10 μg protein in 10,000g supernatant.

All of the mutant TTP proteins migrated faster than WT TTP protein on SDS-PAGE (Figure 2A and 2B, lanes 1 vs. lanes 2−10), in agreement with those in Figure 1A. However, some of the mutant TTP protein bands shown in Figure 1A were collapsed into a single band(s), whereas the bands of the purified proteins shown in Figure 2A and 2B were broad. The immunoblot shown in Figure 1A was obtained from the soluble extracts of transfected HEK293 cells without labeling or purification, whereas those in Figure 2A and 2B were obtained from proteins purified with 100 mM imidazole elution after the cells were labeled with [32P]. It was therefore possible that the fat bands in Figure 2A and 2B were due to more His-TTP proteins in the purified protein samples than those used in Figure 1A. We tested this possibility by performing a dosage analysis using 1, 2, 5, and 10 μg of proteins from two mutant His-TTP proteins: S(88,90,93,197,214,218,228,296,)A and S(197,214,218,228,296)A. Immunoblotting showed that the sizes of TTP protein bands were gradually increased following the increased amounts of proteins used (Figure 2C). These results suggest that the thickness of the mutant TTP protein bands on the immunoblot (Figure 2B) is due in part to the increased amounts of mutant proteins used.

WT His-TTP protein was eluted the most by 100 mM imidazole solution and was more than those by 200 and 250 mM imidazole combined (Table 1). Approximately 20% of His-TTP was still bound to Ni-NTA beads. This elution pattern was different from those of the mutant proteins, in which mutant proteins were eluted the most by 200 mM imidazole, followed by 100 mM and 250 mM (Table 1). Furthermore, more percentages of mutant proteins were bound to Ni-NTA beads after the three elutions than those of WT protein (Table 1). HEK293 cells transfected with mutant plasmids resulted in more soluble protein in the 10,000g supernatant than WT plasmid (Table 1). The yield of total eluted activities in cells transfected with mutant plasmids was approximately twice of those of WT. However, the specific activity of the purified protein between WT and the mutant proteins was less significantly different (Table 1). These results suggest that mutations at the putative phosphorylation sites increased the total soluble protein content and the specific His-TTP expression in the transfected cells.

Table 1. Ni-NTA purification of radioactive His-TTP.

HEK293 cells were transfected with the 10 plasmids. The cells were labeled with [32P]orthophosphate. Soluble proteins in the supernatant (500 μL) of cell extracts were mixed with Ni-NTA. The bound proteins in the beads were extensively washed before elution with 50 μL of 100, 200, and 250 mM imidazole. Radioactivity in each fraction was counted.

| No | Plasmid construct (pHis-TTP) WT and serine (S)/thronine (T) to alanine (A) mutation(s) | Soluble protein (μg/μL) | 100 mM (cpm) (×1000) | 200 mM (cpm) (×1000) | 250 mM (cpm) (×1000) | Beads (cpm) (×1000) | Total (cpm) (×1000) | Bound ratio (beads/total) (%) | Yield (eluted cpm) (×1000) | Eluted ratio (mutant/WT) (%) | Specific activity (cpm/μg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | WT | 0.6 | 159 | 93 | 35 | 79 | 366 | 21.6 | 287 | 100 | 1220 |

| 2 | S197A | 0.8 | 230 | 266 | 103 | 195 | 794 | 24.6 | 599 | 209 | 1990 |

| 3 | S(197,228)A | 1.1 | 268 | 316 | 252 | 455 | 1061 | 42.9 | 606 | 211 | 1930 |

| 4 | S(197,228,218)A | 1.6 | 171 | 176 | 67 | 138 | 552 | 25.0 | 414 | 144 | 690 |

| 5 | S(197,228,218,214)A | 1.1 | 205 | 279 | 115 | 220 | 819 | 26.9 | 599 | 209 | 1490 |

| 6 | S(197,228,218,214,296)A | 1.4 | 189 | 283 | 116 | 377 | 965 | 39.1 | 588 | 205 | 1380 |

| 7 | S(197,228,218,214,296,88)A | 2.0 | 251 | 309 | 137 | 338 | 1035 | 32.7 | 697 | 243 | 1040 |

| 8 | S(197,228,218,214,286,88,186)A | 1.6 | 247 | 345 | 148 | 300 | 1040 | 28.8 | 740 | 258 | 1300 |

| 9 | S(197,228,218,214,296,88)T271A | 1.9 | 206 | 256 | 117 | 391 | 970 | 40.3 | 579 | 202 | 1020 |

| 10 | S(197,228,218,214,296,88,90,93)A | 1.7 | 226 | 292 | 141 | 462 | 1221 | 38.5 | 659 | 230 | 1440 |

Immunoaffinity Purification of WT and Mutant TTP Proteins from Transfected Human Cells

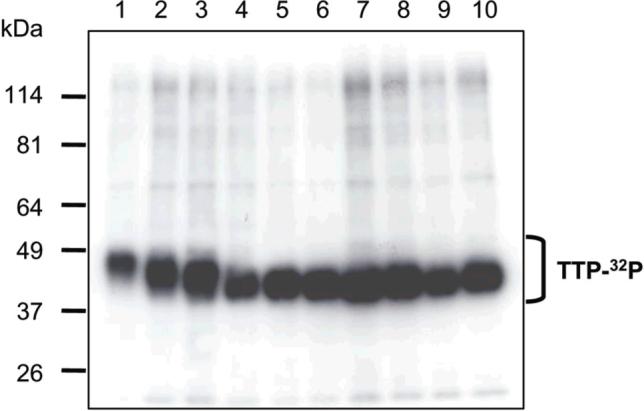

WT and mutant His-TTP proteins were purified from the 10,000g supernatant of soluble extracts from [32P]-orthophosphate-labeled HEK293 cells by IP with TTP antibodies (Figure 3) (35). This purification procedure resulted in more mutant proteins than WT protein (Table 2). However, the specific activities of purified mutant proteins were generally less than WT protein except for the protein with S(197,214, 218, 228)A mutations (Table 2). IP showed that the specific activity of WT TTP proteins was about twice of mutant TTP proteins (Table 2).

Figure 3. IP purification of WT and mutant TTP proteins from radiolabeled HEK293 cells.

HEK293 cells were transfected with the 10 plasmids. The cells were subsequently labeled with [32P]orthophosphate, lysed and centrifuged. Proteins in the supernatant of the soluble extracts were mixed with TTP antiserum. Antibody-antigen complexes were precipitated with Protein A Sepharose CL-4B. The beads were washed three times. The final washed beads were suspended in SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and detected by autoradiography. Lane 1: WT His-TTP, lane 2: His-TTP with S197A mutation, lane 3: His-TTP with S(197,228)A mutations, lane 4: His-TTP with S(197,218,228)A mutations, lane 5: His-TTP with S(197,214,218,228)A mutations, lane 6: His-TTP with S(197,214,218,228,296)A mutations, lane 7: His-TTP with S(88,197,214,218,228,296)A mutations, lane 8: His-TTP with S(88,186,197,214,218,228,296)A mutations, lane 9: His-TTP with S(88,197,214,218,228)T271A mutations, lane 10: His-TTP with S(88,90,93,197,214,218,228,296)A mutations

Table 2. Immunoprecipitation of radioactive His-TTP by TTP antibodies.

HEK293 cells were transfected with the 10 plasmids. The cells were labeled with [32P]-orthophosphate. Soluble proteins in the supernatant (100 μL) of the lysate were mixed with TTP antiserum followed by incubation with Protein A Sepharose CL-4B. The bound proteins precipitated with the beads were extensively washed before radioactivity was counted.

| No | Plasmid construct (pHis-TTP) WT and serine (S)/thronine (T) to alanine (A) mutation(s) | Soluble protein (μg/μL) | Yield (total cpm) (×1000) | Precipitation ratio (mutant/WT) (%) | Specific activity (cpm/μg) | Specific activity (Relative to WT) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | WT | 0.6 | 34 | 100 | 570 | 100 |

| 2 | S197A | 0.8 | 42 | 126 | 530 | 93 |

| 3 | S(197,228)A | 1.1 | 38 | 112 | 350 | 61 |

| 4 | S(197,228,218)A | 1.6 | 62 | 182 | 390 | 68 |

| 5 | S(197,228,218,214)A | 1.1 | 91 | 268 | 830 | 146 |

| 6 | S(197,228,218,214,296)A | 1.4 | 41 | 121 | 290 | 51 |

| 7 | S(197,228,218,214,296,88)A | 2.0 | 42 | 126 | 210 | 37 |

| 8 | S(197,228,218,214,286,88,186)A | 1.6 | 43 | 126 | 270 | 47 |

| 9 | S(197,228,218,214,296,88)T271A | 1.9 | 44 | 129 | 230 | 40 |

| 10 | S(197,228,218,214,296,88,90,93)A | 1.7 | 50 | 147 | 290 | 51 |

Discussion

His-tag affinity purification has been widely used for the purification of recombinant proteins from various overexpression systems. However, the purity and yield of this procedure depend on the proteins to be expressed. Detailed evaluation of this procedure was not performed extensively. This study quantitatively evaluated His-tag procedure and compared it with IP using radiolabeled WT and mutant His-TTP proteins. Radiolabeling of phosphoproteome of transfected HEK293 cells allowed us to perform quantitative analysis of His-TTP purification by both His-tag and IP procedures. The fact that almost all of the purified proteins labeled with [32P] were His-TTP provided the basis for the differentiation between His-TTP and copurified proteins.

One observation was that cells transfected with mutant plasmids yielded more soluble proteins than those with WT. The yield of mutant proteins purified by His-tag procedure was approximately twice that of WT, apparently due to the increased total soluble protein content in the mutant transfection (Table 1). IP also resulted in more mutant proteins than WT (Table 2). It was possible that the lower recovery of WT protein in the soluble fraction was partly due to more WT protein precipitated as insoluble aggregates than the mutant TTP proteins. In our previous study, WT TTP protein was detected in the insoluble fraction and compared to those in the soluble fraction. Approximately 20% of the expressed WT TTP presented in the insoluble fraction and 80% in the soluble fraction (3). Based on the similar immunostaining patterns of the mutant and WT TTP proteins (Figure 1B), we speculate that the great majority of the expressed TTP proteins are presented in the soluble fraction. The low percentage of WT TTP in the insoluble fraction was not sufficient to explain the much less recovery of soluble protein from cells transfected with WT pHis-TTP. The specific activities of the purified proteins between WT and mutant TTP were less significantly different (Table 1), suggesting that it was unlikely that the difference in the quantity of proteins between wild type TTP and mutants could be due to different expression levels of plasmids in the cells. It has been reported that TTP is apoptotic (38). It was therefore possible that WT TTP exhibited more toxic effects towards HEK293 cells than mutant TTP proteins under these culture conditions. Taken together, the increased soluble protein in the mutant transfection might be the reason why more His-TTP proteins were recovered in cells transfected with mutant plasmids than those with WT plasmid.

Another point of interest was that mutations in TTP increased the binding affinity of mutant TTP proteins for Ni-NTA beads. This conclusion was supported by the facts that higher concentrations of imidazole were required to elute out the majority of mutant His-TTP proteins from Ni-NTA beads (200 mM imidazole) than WT (100 mM imidazole) and that more percentages of mutant proteins were still bound to the beads than WT after multiple imidazole elutions.

In addition, our results demonstrated that His-tag purification procedure was more powerful than immunoaffinity purification using TTP antibodies. This was supported by the fact that recoveries of both WT and mutant His-TTP proteins were much higher in His-tag purification that IP.

It was noted that mutant TTP proteins migrated faster on SDS-PAGE than WT TTP protein (Figures 1A, 2A and 2B). Some of the mutant TTP protein bands shown in Figure 1A were collapsed into a single band(s), whereas the purified protein bands shown in Figure 2A and 2B were broad. The fat bands in Figure 2 were due in part to more His-TTP proteins used for the immunoblotting than those used in Figure 1A since more proteins used in the immunoblotting resulted in broader bands on the immunoblot (Figure 2C).

It was also noted that mutant TTP proteins were phosphorylated to similar extent as the WT TTP despite of extensive mutations at the phosphorylation sites in the mutant proteins. One reason could be due to the increased soluble proteins recovered from the cells transfected with mutant plasmids (Figure 2B). Another reason could be that proteins with more severe mutations expose other phosphorylated sites otherwise not phosphorylated or underphosphorylated in the wild type or less mutated proteins. TTP protein is phosphorylated extensively in vivo (3, 4, 35, 39) and is a substrate for a number of protein kinases in vitro (4, 11, 40). Complete identification of TTP phosphorylation sites and associated protein kinases as well as the effects of phosphorylation on TTP functions are active research areas (4, 41-43).

Conclusion

This study evaluated His-tag procedure quantitatively and compared it with immunoprecipitation using radiolabeled TTP expressed in transfected human embryonic kidney 293 cells. The results demonstrated that 1) His-tag purification was more effective than immunoprecipitation for TTP purification; 2) mutations in TTP increased the yield of TTP by both purification procedures; and 3) mutations in TTP increased the binding affinity of mutant proteins for Ni-NTA beads. These findings suggest that production of recombinant proteins can be improved by bioengineering potential phosphorylation sites in the amino acid sequences of proteins of interest.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, and USDA-ARS Human Nutrition Research Program. We thank Dr. Perry J. Blackshear (NIEHS/NIH) for his generous support, Dr. Wi S. Lai for the wild-type and S197A mutant TTP plasmids, Ms. Elizabeth A. Kennington (NIH/NIEHS) for her assistance on radiolabelling, and Dr. Joseph F. Urban Jr. (USDA/ARS) for his helpful comments on the manuscript.

Notation

- ARE

AU-rich element

- DMEM

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

- FCS

fatal calf serum

- GM-CSF

granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- HEK

human embryonic kidney

- IP

immunoprecipitation

- MAP

mitogen-activated protein

- MBP

maltose binding protein

- Ni-NTA

nickel-nitrilotriacetic agarose

- PAGE

polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor alpha

- TTP

tristetraprolin

- WT

wild-type

- ZFP

zinc finger protein

References and Notes

- 1.DuBois RN, McLane MW, Ryder K, Lau LF, Nathans D. A growth factor-inducible nuclear protein with a novel cysteine/histidine repetitive sequence. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:19185–19191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Worthington MT, Amann BT, Nathans D, Berg JM. Metal binding properties and secondary structure of the zinc-binding domain of Nup475. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1996;93:13754–13759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cao H. Expression, purification, and biochemical characterization of the antiinflammatory tristetraprolin: a zinc-dependent mRNA binding protein affected by posttranslational modifications. Biochemistry. 2004;43:13724–13738. doi: 10.1021/bi049014y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cao H, Deterding LJ, Blackshear PJ. Phosphorylation site analysis of the anti-inflammatory and mRNA-destabilizing protein tristetraprolin. Expert. Rev. Proteomics. 2007;4:711–726. doi: 10.1586/14789450.4.6.711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blackshear PJ. Tristetraprolin and other CCCH tandem zinc-finger proteins in the regulation of mRNA turnover. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2002;30:945–952. doi: 10.1042/bst0300945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blackshear PJ, Lai WS, Kennington EA, Brewer G, Wilson GM, Guan X, Zhou P. Characteristics of the interaction of a synthetic human tristetraprolin tandem zinc finger peptide with AU-rich element-containing RNA substrates. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:19947–19955. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301290200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Worthington MT, Pelo JW, Sachedina MA, Applegate JL, Arseneau KO, Pizarro TT. RNA binding properties of the AU-rich element-binding recombinant Nup475/TIS11/tristetraprolin protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:48558–48564. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206505200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hau HH, Walsh RJ, Ogilvie RL, Williams DA, Reilly CS, Bohjanen PR. Tristetraprolin recruits functional mRNA decay complexes to ARE sequences. J. Cell Biochem. 2007;100:1477–1492. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raghavan A, Robison RL, McNabb J, Miller CR, Williams DA, Bohjanen PR. HuA and tristetraprolin are induced following T cell activation and display distinct but overlapping RNA binding specificities. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:47958–47965. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109511200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ditargiani RC, Lee SJ, Wassink S, Michel SL. Functional Characterization of Iron-Substituted Tristetraprolin-2D (TTP-2D, NUP475−2D): RNA Binding Affinity and Selectivity. Biochemistry. 2006;45:13641–13649. doi: 10.1021/bi060747n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cao H, Dzineku F, Blackshear PJ. Expression and purification of recombinant tristetraprolin that can bind to tumor necrosis factor-alpha mRNA and serve as a substrate for mitogen-activated protein kinases. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2003;412:106–120. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(03)00012-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carballo E, Lai WS, Blackshear PJ. Feedback inhibition of macrophage tumor necrosis factor-alpha production by tristetraprolin. Science. 1998;281:1001–1005. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5379.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lai WS, Carballo E, Strum JR, Kennington EA, Phillips RS, Blackshear PJ. Evidence that tristetraprolin binds to AU-rich elements and promotes the deadenylation and destabilization of tumor necrosis factor alpha mRNA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:4311–4323. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.6.4311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carballo E, Lai WS, Blackshear PJ. Evidence that tristetraprolin is a physiological regulator of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor messenger RNA deadenylation and stability. Blood. 2000;95:1891–1899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carballo E, Cao H, Lai WS, Kennington EA, Campbell D, Blackshear PJ. Decreased sensitivity of tristetraprolin-deficient cells to p38 inhibitors suggests the involvement of tristetraprolin in the p38 signaling pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:42580–42587. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104953200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sully G, Dean JL, Wait R, Rawlinson L, Santalucia T, Saklatvala J, Clark AR. Structural and functional dissection of a conserved destabilizing element of cyclo-oxygenase-2 mRNA: evidence against the involvement of AUF-1 [AU-rich element/poly(U)-binding/degradation factor-1], AUF-2, tristetraprolin, HuR (Hu antigen R) or FBP1 (far-upstream-sequence-element-binding protein 1). Biochem. J. 2004;377:629–639. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sawaoka H, Dixon DA, Oates JA, Boutaud O. Tristetraprolin binds to the 3'-untranslated region of cyclooxygenase-2 mRNA. A polyadenylation variant in a cancer cell line lacks the binding site. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:13928–13935. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300016200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ogilvie RL, Abelson M, Hau HH, Vlasova I, Blackshear PJ, Bohjanen PR. Tristetraprolin down-regulates IL-2 gene expression through AU-rich element-mediated mRNA decay. J. Immunol. 2005;174:953–961. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frasca D, Landin AM, Alvarez JP, Blackshear PJ, Riley RL, Blomberg BB. Tristetraprolin, a negative regulator of mRNA stability, is increased in old B cells and is involved in the degradation of e47 mRNA. J. Immunol. 2007;179:918–927. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.2.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phillips K, Kedersha N, Shen L, Blackshear PJ, Anderson P. Arthritis suppressor genes TIA-1 and TTP dampen the expression of tumor necrosis factor alpha, cyclooxygenase 2, and inflammatory arthritis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:2011–2016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400148101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taylor GA, Carballo E, Lee DM, Lai WS, Thompson MJ, Patel DD, Schenkman DI, Gilkeson GS, Broxmeyer HE, Haynes BF, Blackshear PJ. A pathogenetic role for TNF alpha in the syndrome of cachexia, arthritis, and autoimmunity resulting from tristetraprolin (TTP) deficiency. Immunity. 1996;4:445–454. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80411-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sauer I, Schaljo B, Vogl C, Gattermeier I, Kolbe T, Muller M, Blackshear PJ, Kovarik P. Interferons limit inflammatory responses by induction of tristetraprolin. Blood. 2006;107:4790–4797. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-3058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anderson P, Phillips K, Stoecklin G, Kedersha N. Post-transcriptional regulation of proinflammatory proteins. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2004;76:42–47. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1103536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blackshear PJ, Phillips RS, Vazquez-Matias J, Mohrenweiser H. Polymorphisms in the genes encoding members of the tristetraprolin family of human tandem CCCH zinc finger proteins. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 2003;75:43–68. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(03)75002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carrick DM, Lai WS, Blackshear PJ. The tandem CCCH zinc finger protein tristetraprolin and its relevance to cytokine mRNA turnover and arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2004;6:248–264. doi: 10.1186/ar1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seko Y, Cole S, Kasprzak W, Shapiro BA, Ragheb JA. The role of cytokine mRNA stability in the pathogenesis of autoimmune disease. Autoimmun. Rev. 2006;5:299–305. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2005.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lai WS, Parker JS, Grissom SF, Stumpo DJ, Blackshear PJ. Novel mRNA Targets for Tristetraprolin (TTP) Identified by Global Analysis of Stabilized Transcripts in TTP-Deficient Fibroblasts. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006;26:9196–9208. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00945-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thalmeier A, Dickmann M, Giegling I, Schneider B, Hartmann M, Maurer K, Schnabel A, Kauert G, Moller HJ, Rujescu D. Gene expression profiling of post-mortem orbitofrontal cortex in violent suicide victims. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;11:217–228. doi: 10.1017/S1461145707007894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bouchard L, Tchernof A, Deshaies Y, Marceau S, Lescelleur O, Biron S, Vohl MC. ZFP36: a promising candidate gene for obesity-related metabolic complications identified by converging genomics. Obes. Surg. 2007;17:372–382. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9067-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lai WS, Stumpo DJ, Blackshear PJ. Rapid insulin-stimulated accumulation of an mRNA encoding a proline-rich protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:16556–16563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cao H, Urban JF, Jr., Anderson RA. Insulin increases tristetraprolin and decreases VEGF gene expression in mouse 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Obesity (Silver. Spring) 2008;16:1208–1218. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cao H, Kelly MA, Kari F, Dawson HD, Urban JF, Jr., Coves S, Roussel AM, Anderson RA. Green tea increases anti-inflammatory tristetraprolin and decreases pro-inflammatory tumor necrosis factor mRNA levels in rats. J. Inflamm. (Lond) 2007;4:1. doi: 10.1186/1476-9255-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cao H, Polansky MM, Anderson RA. Cinnamon extract and polyphenols affect the expression of tristetraprolin, insulin receptor, and glucose transporter 4 in mouse 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2007;459:214–222. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2006.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cao H, Urban JF, Jr., Anderson RA. Cinnamon polyphenol extract affects immune responses by regulating anti- and proinflammatory and glucose transporter gene expression in mouse macrophages. J. Nutr. 2008;138:833–840. doi: 10.1093/jn/138.5.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cao H, Deterding LJ, Venable JD, Kennington EA, Yates JR, III, Tomer KB, Blackshear PJ. Identification of the anti-inflammatory protein tristetraprolin as a hyperphosphorylated protein by mass spectrometry and site-directed mutagenesis. Biochem. J. 2006;394:285–297. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cao H, Lin R, Ghosh S, Anderson RA, Urban JF., Jr. Production and characterization of ZFP36L1 antiserum against recombinant protein from Escherichia coli. Biotechnol. Prog. 2008;24:326–333. doi: 10.1021/bp070269n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cao H, Tuttle JS, Blackshear PJ. Immunological characterization of tristetraprolin as a low abundance, inducible, stable cytosolic protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:21489–21499. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400900200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnson BA, Blackwell TK. Multiple tristetraprolin sequence domains required to induce apoptosis and modulate responses to TNFalpha through distinct pathways. Oncogene. 2002;21:4237–4246. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chrestensen CA, Schroeder MJ, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Pelo JW, Worthington MT, Sturgill TW. MAPKAP kinase 2 phosphorylates tristetraprolin on in vivo sites including Ser178, a site required for 14−3−3 binding. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:10176–10184. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310486200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cao H, Lin R. Phosphorylation of recombinant tristetraprolin in vitro. Protein J. 2008;27:163–169. doi: 10.1007/s10930-007-9119-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sandler H, Stoecklin G. Control of mRNA decay by phosphorylation of tristetraprolin. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2008;36:491–496. doi: 10.1042/BST0360491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stoecklin G, Stubbs T, Kedersha N, Wax S, Rigby WF, Blackwell TK, Anderson P. MK2-induced tristetraprolin:14−3−3 complexes prevent stress granule association and ARE-mRNA decay. EMBO J. 2004;23:1313–1324. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sun L, Stoecklin G, Van WS, Hinkovska-Galcheva V, Guo RF, Anderson P, Shanley TP. Tristetraprolin (TTP)-14−3−3 complex formation protects TTP from dephosphorylation by protein phosphatase 2a and stabilizes tumor necrosis factor-alpha mRNA. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:3766–3777. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607347200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]