Abstract

HSV-1 glycoprotein D (gD) interacts with HVEM and nectin-1 cell receptors to initiate virus entry. We prepared an HSV-1 strain with mutations in the gD gene at amino acid residues 3 and 38 by changing alanine to cysteine and tyrosine to cysteine, respectively (A3C/Y38C). These mutations were constructed with the intent of evaluating infection in vivo when virus enters by HVEM but not nectin-1 receptors and were based on prior reports demonstrating that purified gDA3C/Y38C protein binds to HVEM but not to nectin-1. While preparing a high titered purified virus pool, the cysteine mutation at position 38 reverted to tyrosine, which occurred on two separate occasions. The resultant HSV-1 strain, KOS-gDA3C, had a single amino acid mutation at residue 3 and exhibited reduced entry into both HVEM and nectin-1 expressing cells. When tested in the murine flank model, the mutant virus was markedly attenuated for virulence and caused only mild disease, while the parental and rescued viruses produced much more severe disease. Thirty days after KOS-gDA3C infection, mice were challenged with a lethal dose of HSV-1 and were highly resistant to disease. The KOS-gDA3C mutation was stable during 30 passages in vitro and was present in each of 3 isolates obtained from infected mice. Therefore, this gD mutant virus impaired in entry may represent a novel candidate for an attenuated live HSV-1 vaccine.

Keywords: HSV, vaccines, glycoprotein D

INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of HSV-1 and HSV-2 infection increases with age and varies considerably worldwide [1]. Approximately 58% of individuals in the USA become infected with HSV-1 and 17% with HSV-2 [2]. HSV-1 is the most common cause of sporadic encephalitis in the USA, which has a high morbidity and mortality despite antiviral therapy [3], [4]. HSV-1 keratitis is the leading infectious cause of blindness in the USA, and a common indication for corneal transplantation [5]. Complications from HSV infection may be severe in the immunocompromised host and neonate [6], [7]. Herpes genitalis is a sexually transmitted infection caused primarily by HSV-2, although in some countries the proportion of genital ulcer disease caused by HSV-1 is rising [8-11]. Herpes genitalis infection increases the risk of acquiring HIV during sexual intercourse by 2- to 4-fold, while HSV-2 infection increases HIV viral load, possibly contributing to higher rates of HIV transmission and disease progression [12].

Vaccines for the prevention of HSV-1 and HSV-2 are urgently needed. Chiron Corporation and GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) performed large-scale human trials to evaluate the safety and efficacy of HSV-2 glycoprotein subunit vaccines [13, 14] The Chiron vaccine formulation included HSV-2 glycoproteins B (gB) and gD in adjuvant MF59, which is an oil-in-water emulsion containing squalene, polysorbate 80, and sorbitan trioleate. The GSK vaccine contains HSV-2 gD in alum and 3-O-deacylated-monophosphoryl lipid A (MPL). HSV-2 acquisition rates, duration of infection and frequency of reactivation were not different in subjects receiving placebo or the Chiron vaccine. Acquisitions of HSV-2 genital lesions following vaccination with the GSK formulation were also not significantly different comparing vaccine and placebo recipients. However, in a subgroup analysis, the vaccine was effective in women who were seronegative to both HSV-1 and -2 prior to vaccination, but not in men or HSV-1 seropositive women. Additional studies are now in progress to confirm the protection in seronegative women. If confirmed, the vaccine may be approved for seronegative women, leaving room for new approaches for prevention in men and seropositive women.

A live replication defective HSV-2 strain deleted in ICP27 or ICP8 has also been evaluated as a vaccine candidate. ICP27 encodes an essential, immediate-early protein involved in regulation of viral gene expression, while ICP8 encodes the single-stranded DNA-binding protein required for viral DNA replication. Studies in animal models have shown excellent protection [15], and human trials have been proposed for the HSV-2 strain. However, producing large quantities for vaccination may be difficult because the virus is replication defective.

As an alternate approach, we evaluated a replication competent HSV strain with a mutation that affects virus entry. We used an HSV-1 strain with the intent that if successful a similar approach could be tried with HSV-2. HSV-1 entry involves multiple cell receptors, including HVEM, nectin-1, nectin-2, and a modified form of heparan sulphate [16-18]. HVEM is a member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor family and is widely expressed on mammalian cells [19]. Both HSV-1 and HSV-2 interact with this receptor [19, 20]. Nectin-1 and nectin-2 are related to the poliovirus receptor and are members of the Ig superfamily [21-23]. Nectin-1 and nectin-2 are cell adhesion molecules detected at cell junctions and are expressed on many mammalian cells [24, 25]. Nectin-1 supports HSV-1 and HSV-2 entry, while nectin-2 interacts with HSV-2, but not HSV-1 [21, 22, 26]. Modified heparan sulphate is a receptor for HSV-1 alone [17, 18].

HSV-1 membrane glycoproteins gB, gD, gH and gL are all required for virus entry [16, 27, 28]. The interaction between gD and cellular receptors is thought to trigger downstream events involving gB, gH and gL that result in fusion of the viral envelope with cell membranes [29, 30, 31]. The domains on gD that interact with HVEM and nectin-1 have been defined by mutagenesis analysis and by resolving the crystal structure of gD or gD bound to HVEM [31-40]. The gD amino terminus (residue-1 to 15) is disordered in the crystal structure of gD; however, when bound to HVEM the amino terminus assumes a hairpin loop structure [33]. We replaced the alanine and tyrosine residues at gD amino acids 3 and 38 respectively with cysteine residues (A3C/Y38C) to create a 3-38 disulfide bond and a fixed hairpin loop at the amino terminus [37]. The resultant gD mutant protein lost the ability to interact with nectin-1, but retained the ability to bind HVEM in vitro.

We attempted to insert the gD gene with the A3C/Y38C mutations into the HSV-1 genome to develop a mutant virus that enters cells using HVEM but not nectin-1 receptors. However, the amino acid 38 mutation was unstable and reverted to wild-type (WT). The resultant strain, KOS-gDA3C had a single amino acid substitution in gD at position 3 (A3C). We evaluated the stability, entry phenotype, and virulence of this mutant virus and conclude that the mutant strain may be effective as an attenuated live virus vaccine.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and Viruses

Vero cells were grown in Dulbecco's minimum essential medium (DMEM), supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). B78-H1 cells are mouse melanoma cells that are non-permissive for HSV-1 entry, and were grown in DMEM with 5% FCS. B78-H1-A10 (A10) and B78-H1-C10 (C10) cells stably express HVEM and nectin-1, respectively and were grown in DMEM containing 5% FCS and 500μg/ml of G418 [41].

The HSV-1 gD-null virus was derived from KOS and propagated in Vero cells stably transfected with gD DNA (VD60 cells) [42, 43]. HSV-1 strain NS, a low passage clinical isolate, was used for challenge studies [44]. Viruses were grown in Vero cells, unless otherwise noted, purified on sucrose gradients and stored at -80°C [45].

Construction of gDA3C/Y38C and rescued viruses

Plasmid pSC594 was constructed by inserting A3C and Y38C mutations in pRM416 using the Quick Change Site Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene Cloning Systems). Plasmid pRM416 contains the KOS gD open reading frame flanked by 474 base-pairs 5' and 985 base-pairs 3' of the open reading frame. HSV-1 gD-null DNA and pSC594 DNA were co-transfected into VD60 cells using Gene Porter-2 (Gene Therapy Systems). Recombinant virus was screened by replication in Vero cells and then plaque purified. After each plaque purification, 600 base pairs were amplified by PCR at the 5' end of the gD gene, which is the site that contains the mutations. The amplified gD fragments were screened by restriction enzyme mapping, since a new SspI site indicates the presence of the A3C mutation and loss of an RsaI site supports the Y38C mutation. Two separate clones of KOS-gDA3C/Y38C were identified, plaque purified 4 times, and after each plaque purification DNA sequencing was performed to confirm the presence of the A3C/Y38C mutations. The two clones were grown to high titers on Vero cells, purified on a 10% to 60% sucrose gradient, and subjected to DNA sequence analysis and restriction mapping. In both clones, only the A3C mutation remained. These clones contained tyrosine at amino acid 38 indicative of reversion to WT at this residue. We further purified KOS-gDA3C on a sucrose gradient and sequenced the entire gD gene to confirm the presence of the A3C mutation and the absence of additional unintended mutations.

A rescue of the KOS-gDA3C virus was generated by co-transfection of Vero cells with KOS-gDA3C and pRM416 DNA. The rescued strain, referred to as rKOS-gDA3C was plaque purified four times, purified on a sucrose gradient, and the gD gene screened by restriction mapping and DNA sequencing.

Inoculation and zosteriform site disease in the murine flank model

Five to six week old BALB/c female mice (Charles River) were anesthetized and their flanks shaved and chemically denuded [46]. Twenty-four hours later, mice were inoculated with purified KOS, rKOS-gDA3C, or KOS-gDA3C virus by scratching 5×105 PFU/10μl onto the skin using the bevel of a 27-gauge needle. Mice were scored for inoculation and zosteriform site disease. Scores at the inoculation site ranged from 0 to 5 and at the zosteriform site from 0 to 10. One point was assigned per vesicle or if lesions were confluent multiple points were assigned based on the size of the confluent lesions [47].

Entry assay

Four hundred PFU of KOS-gDA3C, rKOS-gDA3C or KOS were incubated for one hour at 4°C with B78-H1, A10, or C10 cells [35, 41, 48]. Cells were warmed to 37°C for 0, 10, 30, 60 or 120 minutes followed by washing to remove unbound virus and treated with citrate buffer pH 3.0 for 1 minute to inactivate virus that had bound but not entered cells. After an additional wash, cells were overlaid with 0.6% low-melt agar in DMEM, and plaques were counted after 68 hours.

Single-step and multi-step growth curves

Single-step growth curves were performed on B78-H1, A10 and C10 cells inoculated with KOS, KOS-gDA3C or rKOS-gDA3C at an MOI of 3. After one hour at 37°C, cells were treated with citrate buffer pH 3.0 for one minute, and cells and supernatant fluids were collected immediately (time 0) or at 2, 4, 8, 12, 20 and 24 hours [49]. Samples were freeze-thawed, sonicated three times and titered on Vero cells. Multi-step growth curves were performed in a similar fashion, except infection was performed at an MOI of 0.01 and titers measured at 24, 48 and 72 hours.

Real-time quantitative PCR for viral DNA

Dorsal root ganglia (DRG) that innervate the inoculation site were harvested and DNA was isolated using the Qia Amp-mini DNA kit (Qiagen). The Us9 gene was amplified by performing the PCR reaction in 50μl containing 200ng of DRG DNA. Fifty pmol of forward 5'cgacgccttaataccgactgtt and reverse 5'acagcgcgatccgacatgtc primers and 15 pmol of Taqman probe 5'tcgttggccgcctcgtcttcgct were added. One unit of Ampli Taq Gold (Applied Bioscience) per 50μl reaction was added. Real time PCR amplification was performed on an ABI Prism7700 Sequence Detector (Applied Biosystems). A standard curve was generated from purified HSV-1 (strain NS) DNA. Mouse adipsin, a cellular housekeeping gene was also amplified from the DRG DNA under identical conditions as an internal control. The primers used for amplification were forward 5'gatgcagtcgaaggtgtggtta and reverse 5' cggtaggatgacactcgggtat, while Taqman probe 5'tctcgcgtctgtggcaatggc was used for detection. The viral DNA copies were then normalized based on the murine adipsin copy number.

Statistics

Area Under the Curve (AUC) was calculated and a t-Test performed to determine P values.

RESULTS

Characterization and stability of KOS-gDA3C mutant strain in vitro and in vivo

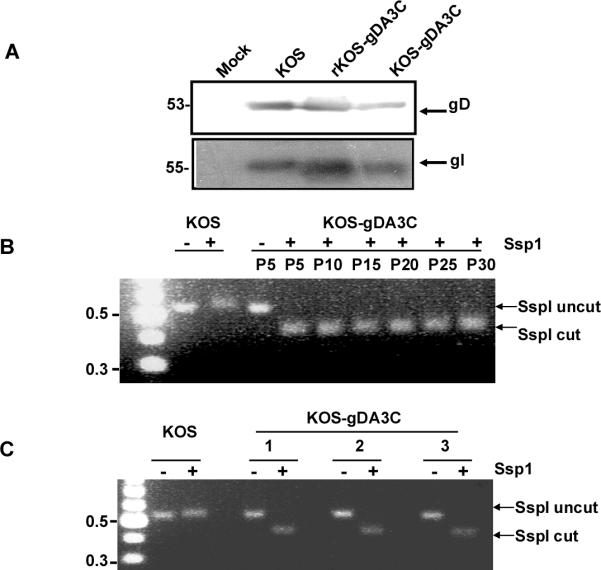

The gD gene (Us6) is situated between gJ (Us5) and gI (Us7); therefore, we evaluated the gD protein and the integrity of the adjacent genes [50]. The molecular mass of the gD and gI proteins by Western blot were similar for WT, rKOS-gDA3C, and KOS-gDA3C (Fig. 1A), while DNA sequencing confirmed the integrity of the gJ gene in KOS-gDA3C (result not shown).

Figure 1. Characterization and stability of KOS-gDA3C virus.

A. Western blot to detect gD (Us6) and gI (Us7) in infected cell extracts. Vero cells were mock infected or infected with KOS, rKOS-gDA3C, or KOS-gDA3C and probed for gD or gI. The position of molecular weight markers is indicated on the left. B. Stability of the KOS-gDA3C virus in vitro. Agarose gel showing Ssp1 digestion of PCR-amplified gD gene fragments of KOS or KOS-gDA3C repeated every fifth passage from passage 5 (P5) to passage 30 (P30). C. Stability of the KOS-gDA3C mutant virus in vivo. A PCR-amplified gD fragment from three different isolates obtained from the DRG of KOS-gDA3C infected mice was cut with Ssp1 or left uncut. A 100 base pair DNA ladder indicating 0.5 and 0.3 kb markers is shown on the left in (B) and (C).

To evaluate the stability of the gDA3C mutation, KOS-gDA3C was passed in Vero cells 30 times and DNA isolated after every five passages. PCR-amplified DNA fragments were analyzed by Ssp1 restriction digestion. The Ssp1 site was maintained through 30 passages, suggesting that the change of alanine to cysteine at residue 3 was stable (Fig. 1B). This result was confirmed by DNA sequence analysis after every five passages. The stability of the gDA3C mutation was further evaluated in vivo. Mice were scratch inoculated on the flank with KOS-gDA3C, and DRG harvested five days post-infection. Virus was isolated from three individual plaques. All three isolates retained the Ssp1 site (Fig. 1C) and the cysteine residue at amino acid 3 as demonstrated by DNA sequencing.

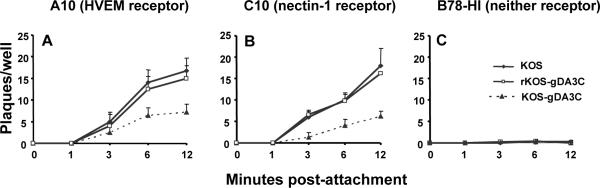

Entry of KOS-gDA3C into HVEM or nectin-1 expressing B78-H1 cells

We evaluated the entry of KOS, rKOS-gDA3C, and KOS-gDA3C into mouse melanoma cells that express HVEM (A10), nectin-1 (C10), or neither (B78-H1) receptor. Virus was grown in Vero cells and 400 PFU was added to A10, C10 or B78-H1 cells. Entry of KOS-gDA3C into A10 and C10 cells was reduced compared with KOS or rKOS-gDA3C (Fig. 2A and 2B), while each virus failed to enter B78-H1 cells (Fig. 2C). Therefore, the gDA3C mutation reduces entry mediated by both HVEM and nectin-1 receptors.

Figure 2. Entry of KOS, rKOS-gDA3C and KOS-gDA3C virus.

Entry was measured into (A) A10, (B) C10, or (C) B78-H1 cells. Results are the mean ± SE of three separate infections each done in triplicate. The AUC for KOS-gDA3C is significantly less than KOS or r-KOS-gDA3C in (A) or (B) (P < 0.001).

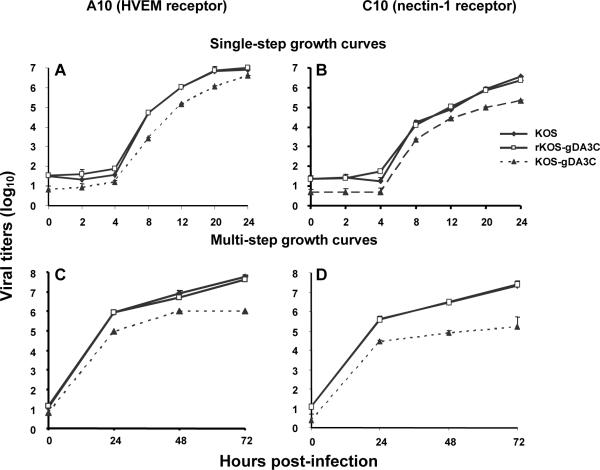

Growth curves of KOS-gDA3C in HVEM or nectin-1 expressing B78-H1 cells

We examined virus replication by performing single-step growth curves at an MOI of 3. KOS, rKOS-gDA3C and KOS-gDA3C failed to replicate in B78-H1 cells (results not shown). Replication of the three viruses was comparable in A10 cells (Fig. 3A) and C10 cells (Fig. 3B), except that the titers of KOS-gDA3C were reduced at the end of the one-hour adsorption period (referred to as time 0), which likely reflects the entry defect described in figure 2.

Figure 3. Growth curves.

Single-step (A, B) and multi-step (C, D) growth curves of KOS, rKOS-gDA3C and KOS-gDA3C were performed in A10 (A, C) or C10 (B, D) cells. Results are the mean ± SE of three separate infections. The AUC for KOS-gDA3C is significantly less than KOS or rKOS-gDA3C in (C) and (D) (P < 0.01 and < 0.001, respectively), while differences among the viruses are not significant in (A) and (B).

We performed multi-step growth curves at an MOI of 0.01 to allow multiple cycles of virus replication. Compared with KOS and rKOS-gDA3C, peak titers of KOS-gDA3C were reduced at 72 hours by approximately 1.5 log10 in A10 cells (Fig. 3C) and 2 log10 in C10 cells (Fig. 3D), which is consistent with defects in entry into both A10 and C10 cells.

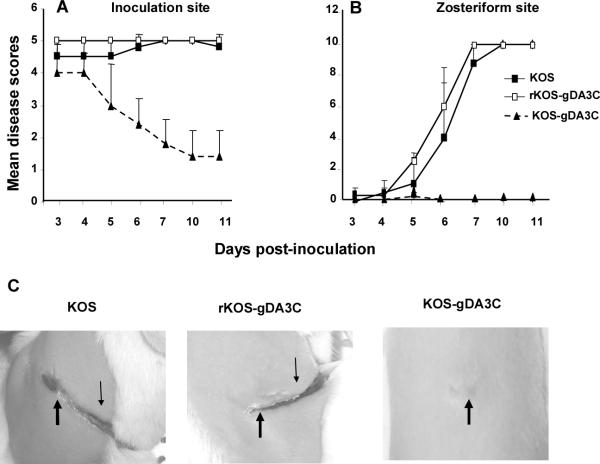

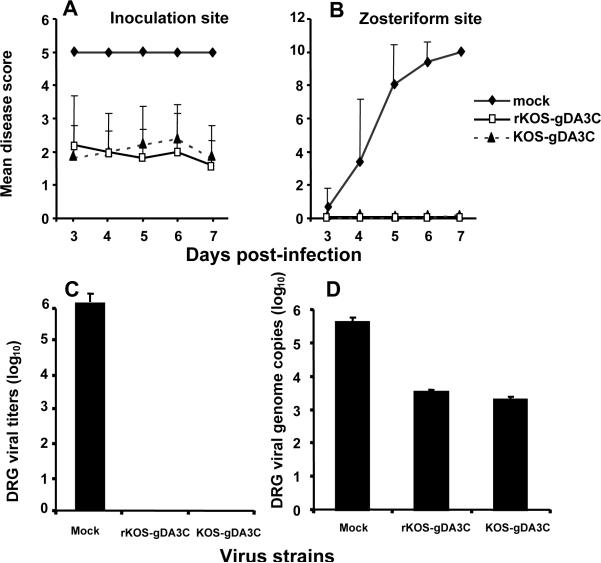

KOS-gDA3C in the mouse flank model

The mouse flank model was used to evaluate the virulence of the KOS-gDA3C mutant. Mice were infected with 5×105 PFU of KOS, rKOS-gDA3C, or KOS-gDA3C and animals scored for disease at the inoculation and zosteriform sites. Mice infected with KOS-gDA3C had significantly less disease at the inoculation site over the course of the infection (Fig. 4A) and almost no zosteriform disease with only one of 30 mice developing 3 lesions on day 5 (Fig. 4B). All mice in the three groups survived. Photographs of inoculation and zosteriform site disease are shown on day 10 (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4. Disease in the murine flank model.

Inoculation (A) and zosteriform (B) site disease scores in mice inoculated with 5×105 PFU of KOS, rKOS-gDA3C or KOS-gDA3C. Thirty mice are in the KOS and KOS-gDA3C groups, and 10 mice are in the rKOS-gDA3C group. Error bars represent SE. The AUC for KOS-gDA3C is significantly less than for the other two viruses at the inoculation (P < .001) and zosteriform (P < .001) sites. C. Photographs of mice flanks taken 10 days post-infection. The mouse infected with KOS or rKOS-gDA3C has extensive inoculation (thick arrow) and zosteriform site disease (thin arrow), while the mouse inoculated with KOS-gDA3C has only minimal disease at the inoculation site and no zosteriform site disease.

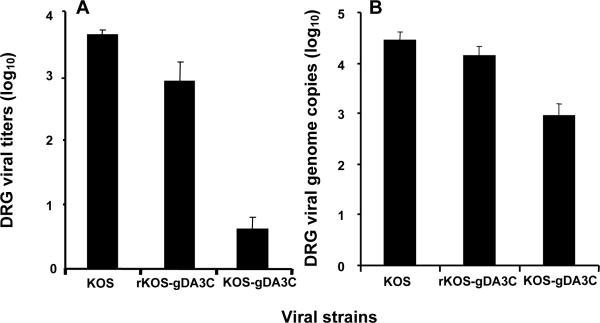

Virus titers and genome copy number in DRG

The reduced zosteriform disease after KOS-gDA3C infection suggests that this mutant virus may be defective in reaching the DRG. Mice were inoculated with 5×105 PFU of KOS, rKOS-gDA3C, or KOS-gDA3C and 5 days post-infection DRG were harvested to measure viral titers (Fig. 5A) and viral genome copy number (Fig. 5B). Both the titers and genome copy number were reduced for KOS-gDA3C compared with KOS or rKOS-gDA3C.

Figure 5. Virus titers and genome copy numbers in DRG.

DRG from mice infected with KOS, rKOS-gDA3C or KOS-gDA3C were assayed for virus titers (A) or viral genome copy number (B). Five animals are in each group. Results represent the mean ± SE. Comparing viral titers or genome copy number for KOS-gDA3C with rKOS-gDA3C or KOS, P < .001, while differences between KOS and rKOS-gDA3C are not significant, P = 0.07.

KOS-gDA3C as an attenuated live virus vaccine

We decided to evaluate KOS-gDA3C as a possible live virus vaccine based on the mild disease caused by this mutant strain. Mice were mock immunized or infected with 5×105 PFU of rKOS-gDA3C or KOS-gDA3C and allowed to recover from the infection. Although rKOS-gDA3C produced extensive disease, all animals survived. Thirty days later, mice were challenged on the opposite flank with HSV-1 strain NS at 106 PFU (approximately 20 LD50). The challenge virus caused extensive disease at the inoculation (Fig. 6A) and zosteriform (Fig. 6B) sites in the mock group. KOS-gDA3C and rKOS-gDA3C protected against disease at the inoculation site and both viruses totally prevented zosteriform disease. None of the rKOS-gDA3C or KOS-gDA3C infected mice died after the NS strain challenge, while 100% of the mock-infected mice died (result not shown). Therefore, KOS-gDA3C provided protection against challenge that was comparable to protection provided by the much more virulent rKOS-gDA3C.

Figure 6. Prior infection with KOS-gDA3C protects against WT HSV-1 challenge.

Mice were mock immunized or infected with 5×105 PFU rKOS-gDA3C or KOS-gDA3C. Thirty days later, mice were challenged on the opposite flank with 106 PFU of WT HSV-1 strain NS. Ten mice were evaluated in each group. Results represent mean disease scores ± SE at the inoculation (A) and zosteriform (B) sites from days 3-7 post-infection (comparing rKOS-gDA3C or KOS-gDA3C with mock-infected mice, P < 0.001). DRG viral titers (C) and genome copy number (D) were measured 5 days post-challenge with NS. Five mice were assayed in each group. Results represent the mean ± SE. The rKOS-gDA3C and KOS-gDA3C values in figures (C) and (D) are both significantly less than mock immunized (P < 0.001).

In a separate experiment, DRG that innervate the challenge site were harvested five days post-challenge and virus quantified by titers and qPCR. HSV-1 titers were approximately 6 log10 in DRG of mock-immunized mice, while no virus was recovered from DRG of mice previously infected with rKOS-gDA3C or KOS-gDA3C (Fig. 6C). When evaluated by qPCR, approximately 5.8 log10 HSV-1 genome copies were detected in DRG of mock-immunized mice compared with 3.4 or 3.2 log10 DNA copies in mice previously infected with rKOS-gDA3C or KOS-gDA3C, respectively (Fig. 6D). Therefore, KOS-gDA3C is attenuated in causing skin lesions at the inoculation and zosteriform sites and in infecting DRG, yet it is as effective as rKOS-gDA3C in protecting mice against WT HSV-1 challenge.

DISCUSSION

Previously, a gD-null pseudotype virus complemented with gDA3C/Y38C was reported to bind to HVEM but not to nectin-1 receptors [37]. We attempted to incorporate this mutation into the HSV-1 genome to make a mutant virus instead of a pseudotype strain; however, the mutation was unstable, which suggests a critical role for nectin-1 in HSV-1 infection. The importance of nectin-1 in HSV-1 infection is supported by results with another gD-null pseudotype virus that has mutations in gD at amino acids 222, 223 and 215 (R222N/F223I/D215G), since this virus fails to bind to nectin-1 receptors and does not infect human cultured epithelial and neuronal cell lines [38].

The KOS-gDA3C virus was stable over 30 passages in vitro and when isolated from mouse DRG. The mutant virus was partially impaired in entry using HVEM or nectin-1 receptors. Surprisingly, the rather modest defect in virus entry resulted in considerable attenuation of virulence in the mouse flank model. Mice inoculated with the gD mutant virus developed minimal disease at the inoculation site and only one of 30 mice developed zosteriform lesions. We detected 2-3 log10 less infectious virus and 1-1.5 log10 fewer genome copies in DRG of mice infected with KOS-gDA3C than KOS or rKOS-gDA3C. The smaller decrease in genome copies than virus titers may indicate that not all viral DNA detected in ganglia represents infectious virus. We do not consider infectious KOS-gDA3C virus in the DRG a contraindication for pursuing gD entry-impaired virus as a vaccine candidate since live attenuated varicella zoster virus vaccine is safe and highly effective in humans despite vaccine virus infecting the ganglia [51].

The first 15 amino acids were disordered in the crystal structure of gD; therefore, we cannot comment on the impact of the gDA3C mutation on gD structure [32]. Deletion of the first 32 gD amino acids reduces binding to HVEM but not to nectin-1, yet the gDA3C mutation significantly modifies virus entry into both HVEM and nectin-1 expressing cells [52]. One possible explanation is that the cysteine at position 3 affects gD conformation, which modifies entry by both receptors. A second possibility relates to the different methods used to prepare the gD mutant viruses. The previous study used a pseudovirus, while we report a genetic recombinant virus constructed by replacing the WT gD gene with the mutant gD DNA [37]. A pseudovirus may differ from a mutant virus in the level of gD expression on the virion envelope or in its ability to form oligomers.

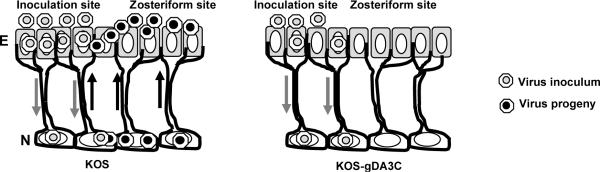

HSV-1 must infect many cells sequentially to develop zosteriform disease, including epithelial cells at the inoculation site, neurons that innervate the skin, neurons adjacent to one another in DRG, and finally epithelial cells at the zosteriform site (see model, Fig. 7). We postulate that reduced entry of KOS-gDA3C decreases the efficiency of infection of the many cells required to cause zosteriform lesions, which enables more time for host innate and acquired immune responses to control the infection.

Figure 7. Model for KOS-gDA3C infection in mice.

KOS infects epithelial cells (E) and produces disease at the inoculation site. The virus spreads to neurons (N) in the DRG, replicates and spreads to adjacent neurons and then travels back to epithelial cells in the skin to cause zosteriform disease. KOS-gDA3C is impaired in entry and infects fewer epithelial cells, which results in fewer neurons becoming infected in the DRG. The defect in entry also reduces infection of adjacent neurons in the DRG and results in reduced zosteriform disease.

It is currently unknown the extent of attenuation that is optimal for a live virus vaccine. If too attenuated, the vaccine will be safe, but may not be effective, while if too virulent, the vaccine may be effective but not safe. The KOS-gDA3C mutant is significantly less virulent than WT or rescued virus, yet it is as protective against WT virus challenge as the rescued strain. Of particular interest is the observation that the gD mutant virus protects the DRG from WT virus challenge. No infectious virus was isolated from DRG five days after challenge, although viral DNA was detected by qPCR. Future studies to assess whether the challenge virus establishes latency within the DRG will be required to determine whether the protection is partial or complete.

A potential concern with KOS-gDA3C is that it contains only a single amino acid mutation at residue 3. Although the mutation was stable over time, modifications in other amino acids adjacent to gD amino acid 3 may be required to reduce the possibility of reversion to WT virus. A possible application of our results is to incorporate the gDA3C mutation into a candidate live virus vaccine that also has mutations in other genes with the goal of further attenuating virulence without modifying immunogenicity.

Additional studies are indicated to determine whether the KOS-gDA3C strain is attenuated in other HSV animal models, such as the guinea pig vaginal infection model, and whether a mutation in HSV-2 gD at a similar residue modifies virulence of HSV-2. Vero cells were used to prepare virus pools for the animal studies, including pools of KOS-gDA3C. The gD mutation at residue 3 did not prevent growing high titers of KOS-gDA3C, suggesting that the entry defect will not limit production of this mutant strain as a live virus vaccine.

We propose that a live virus vaccine for HSV prevention has merit. This opinion is bolstered by the success of other live virus vaccines, including the varicella-zoster virus vaccine. The somewhat limited effectiveness of a gD subunit vaccine, which provided only partial protection in women and no protection in men, also supports pursuing other options [13, 14].

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grants AI056045, HL28220, and AI33063. We thank Richard Milne and Sarah Connolly for pRM416 and pSC594 constructs.

REFERENCES

- [1].Smith JS, Robinson NJ. Age specific prevalence of infection with herpes simplex virus type 2 and 1: a global review. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2002;186:S3–28. doi: 10.1086/343739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Xu Y, Sternberg MR, Kottiri BJ, McQuillan GM, Lee FK, Nehmias AJ, Barman SM, Markowitz LE. Trends in herpes simplex type 1 and type 2 seroprevalence in the United States. JAMA. 2006;296:964–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.8.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Whitley Rj, Lakeman F. Herpes virus infections of central nervous system: therapeutic and diagnostic considerations. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 1995;20:414–20. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.2.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Raschilas FWM, Delatour F, Chaffaut C, De Broucker T, Chevret S, Lebon P, Canton P, Rozenberg F. Outcome of and prognostic factors for herpes simplex encephalitis in adult patients: results of a multicenter study. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2002;35:254–60. doi: 10.1086/341405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Liesegang TJ. Epidemology of ocular herpes simplex. Natural history in Rochester, Minn, 1950 through 1982. Archives of Ophthalmology. 1889;107:171–85. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1989.01070020226030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Genereau T, Lortholary O, Bouchaud O, Lacassin F, Vinceneux P, De Truchis P, et al. Herpes simplex esophagitis in patients with AIDS: report of 34 cases. The Cooperative Study Group on Herpetic Esophagitis in HIV infection. Clinical Infectious Disease. 1996;22:926–31. doi: 10.1093/clinids/22.6.926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Brown ZA, Benedetti J, Ashley R, Burchett S, Selke S, Berry S, et al. Neonatal herpes simplex virus infection in relation to asymptomatic maternal infection at the time of labor. New England Journal of Medicine. 1991;324(18):1247–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199105023241804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lafferty WE, Downey L, Celum C, Wald A. Herpes simplex virus type 1 as a cause of genital herpes: impact on surveillance and prevention. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2000;181(4):1454–7. doi: 10.1086/315395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Cheong WK, Thirumoorthy T, Doraisingham S, Ling AE. Clinical and laboratory study of first episode genital herpes in Singapore. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 1990;1(3):195–8. doi: 10.1177/095646249000100309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Rodgers CA, O'Mahony C. High prevalence of herpes simplex virus type 1 in female anogenital herpes simplex. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 1995;6(2):144. doi: 10.1177/095646249500600218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Christie SN, McCaughey C, McBride M, Coyle PV. Herpes simplex type 1 and genital herpes in Northern Ireland. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 1997;8(1):68–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Corey L, Wald A, Celum CL, Quinn TC. The effects of herpes simplex virus-2 on HIV-1 acquisition and transmission: a review of two overlapping epidemics. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes: JAIDS. 2004;35(5):435–45. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200404150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Corey L, Langenberg AG, Ashley R, Sekulovich RE, Izu AE, Douglas JM, Jr., et al. Recombinant glycoprotein vaccine for the prevention of genital HSV-2 infection: two randomized controlled trials. Chiron HSV Vaccine Study Group. JAMA. 1999;282(4):331–40. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.4.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Stanberry LR, Spruance SL, Cunningham AL, Bernstein DI, Mindel A, Sacks S, et al. Glycoprotein-D-adjuvant vaccine to prevent genital herpes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;347(21):1652–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Da Costa XJ, Morrison LA, Knipe DM. Comparison of different forms of herpes simplex replication-defective mutant viruses as vaccines in a mouse model of HSV-2 genital infection. Virology. 2001;288(2):256–63. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Spear PG, Eisenberg RJ, Cohen GH. Three classes of cell surface receptors for alphaherpesvirus entry. Virology. 2000;275(1):1–8. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Shukla D, Liu J, Blaiklock P, Shworak NW, Bai X, Esko JD, et al. A novel role for 3-O-sulfated heparan sulfate in herpes simplex virus 1 entry. Cell. 1999;99(1):13–22. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Shukla D, Spear PG. Herpesviruses and heparan sulfate: an intimate relationship in aid of viral entry. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2001;108(4):503–10. doi: 10.1172/JCI13799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Montgomery RI, Warner MS, Lum BJ, Spear PG. Herpes simplex virus-1 entry into cells mediated by a novel member of the TNF/NGF receptor family. Cell. 1996;87(3):427–36. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81363-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Whitbeck JC, Peng C, Lou H, Xu R, Willis SH, Ponce de Leon M, et al. Glycoprotein D of herpes simplex virus (HSV) binds directly to HVEM, a member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily and a mediator of HSV entry. Journal of Virology. 1997;71(8):6083–93. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.6083-6093.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Warner MS, Geraghty RJ, Martinez WM, Montgomery RI, Whitbeck JC, Xu R, et al. A cell surface protein with herpesvirus entry activity (HveB) confers susceptibility to infection by mutants of herpes simplex virus type 1, herpes simplex virus type 2, and pseudorabies virus. Virology. 1998;246(1):179–89. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Geraghty RJ, Krummenacher C, Cohen GH, Eisenberg RJ, Spear PG. Entry of alphaherpesviruses mediated by poliovirus receptor-related protein 1 and poliovirus receptor. Science. 1998;280(5369):1618–20. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5369.1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Cocchi F, Menotti L, Mirandola P, Lopez M, Campadelli-Fiume G. The ectodomain of a novel member of the immunoglobulin subfamily related to the poliovirus receptor has the attributes of a bona fide receptor for herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 in human cells. Journal of Virology. 1998;72(12):9992–10002. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.9992-10002.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Takai Y, Nakanishi H. Nectin and afadin: novel organizers of intercellular junctions. Journal of Cell Science. 2003;116(Pt 1):17–27. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Takai Y, Irie K, Shimizu K, Sakisaka T, Ikeda W. Nectins and nectin-like molecules: roles in cell adhesion, migration, and polarization. Cancer Science. 2003;94(8):655–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2003.tb01499.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Krummenacher C, Baribaud F, Ponce de Leon M, Baribaud I, Whitbeck JC, Xu R, et al. Comparative usage of herpesvirus entry mediator A and nectin-1 by laboratory strains and clinical isolates of herpes simplex virus. Virology. 2004;322(2):286–99. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Turner A, Bruun B, Minson T, Browne H. Glycoproteins gB, gD, and gHgL of herpes simplex virus type 1 are necessary and sufficient to mediate membrane fusion in a Cos cell transfection system. Journal of Virology. 1998;72(1):873–5. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.873-875.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Spear PG, Longnecker R. Herpesvirus entry: an update. Journal of Virology. 2003;77(19):10179–85. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.19.10179-10185.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Fuller AO, Lee WC. Herpes simplex virus type 1 entry through a cascade of virus-cell interactions requires different roles of gD and gH in penetration. Journal of Virology. 1992;66(8):5002–12. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.8.5002-5012.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Handler CG, Cohen GH, Eisenberg RJ. Cross-linking of glycoprotein oligomers during herpes simplex virus type 1 entry. Journal of Virology. 1996;70(9):6076–82. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.6076-6082.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Cocchi F, Fusco D, Menotti L, Gianni T, Eisenberg RJ, Cohen GH, et al. The soluble ectodomain of herpes simplex virus gD contains a membrane-proximal pro-fusion domain and suffices to mediate virus entry. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America; 2004. pp. 7445–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Carfi A, Willis SH, Whitbeck JC, Krummenacher C, Cohen GH, Eisenberg RJ, et al. Herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D bound to the human receptor HveA. Molecular Cell. 2001;8(1):169–79. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00298-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Carfi A, Gong H, Lou H, Willis SH, Cohen GH, Eisenberg RJ, et al. Crystallization and preliminary diffraction studies of the ectodomain of the envelope glycoprotein D from herpes simplex virus 1 alone and in complex with the ectodomain of the human receptor HveA. Acta Crystallographica Section D-Biological Crystallography. 2002;58(Pt 5):836–8. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902001270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Connolly SA, Landsburg DJ, Carfi A, Wiley DC, Eisenberg RJ, Cohen GH. Structure-based analysis of the herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D binding site present on herpesvirus entry mediator HveA (HVEM) Journal of Virology. 2002;76(21):10894–904. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.21.10894-10904.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Connolly SA, Landsburg DJ, Carfi A, Wiley DC, Cohen GH, Eisenberg RJ. Structure-based mutagenesis of herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D defines three critical regions at the gD-HveA/HVEM binding interface. Journal of Virology. 2003;77(14):8127–40. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.14.8127-8140.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Whitbeck JC, Connolly SA, Willis SH, Hou W, Krummenacher C, Ponce de Leon M, et al. Localization of the gD-binding region of the human herpes simplex virus receptor, HveA. Journal of Virology. 2001;75(1):171–80. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.1.171-180.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Connolly SA, Landsburg DJ, Carfi A, Whitbeck JC, Zuo Y, Wiley DC, et al. Potential nectin-1 binding site on herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D. Journal of Virology. 2005;79(2):1282–95. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.2.1282-1295.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Manoj S, Jogger CR, Myscofski D, Yoon M, Spear PG. Mutations in herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D that prevent cell entry via nectins and alter cell tropism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America; 2004. pp. 12414–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Krummenacher C, Rux AH, Whitbeck JC, Ponce-de-Leon M, Lou H, Baribaud I, et al. The first immunoglobulin-like domain of HveC is sufficient to bind herpes simplex virus gD with full affinity, while the third domain is involved in oligomerization of HveC. Journal of Virology. 1999;73(10):8127–37. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8127-8137.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Krummenacher C, Supekar VM, Whitbeck JC, Lazear E, Connolly SA, Eisenberg RJ, et al. Structure of unliganded HSV gD reveals a mechanism for receptor-mediated activation of virus entry. EMBO Journal. 2005;24(23):4144–53. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Miller CG, Krummenacher C, Eisenberg RJ, Cohen GH, Fraser NW. Development of a syngenic murine B16 cell line-derived melanoma susceptible to destruction by neuroattenuated HSV-1. Molecular Therapy: the Journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2001;3(2):160–8. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2000.0240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Dean HJ, Terhune SS, Shieh MT, Susmarski N, Spear PG. Single amino acid substitutions in gD of herpes simplex virus 1 confer resistance to gD-mediated interference and cause cell-type-dependent alterations in infectivity. Virology. 1994;199(1):67–80. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Ligas MW, Johnson DC. A herpes simplex virus mutant in which glycoprotein D sequences are replaced by beta-galactosidase sequences binds to but is unable to penetrate into cells. Journal of Virology. 1888;62(5):1486–94. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.5.1486-1494.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Nagashunmugam T, Lubinski J, Wang L, Goldstein LT, Weeks BS, Sundaresan P, et al. In vivo immune evasion mediated by the herpes simplex virus type 1 immunoglobulin G Fc receptor. Journal of Virology. 1998;72(7):5351–9. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.5351-5359.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Friedman HM, Wang L, Fishman NO, Lambris JD, Eisenberg RJ, Cohen GH, et al. Immune evasion properties of herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoprotein gC. Journal of Virology. 1996;70(7):4253–60. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.7.4253-4260.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Judson KA, Lubinski JM, Jiang M, Chang Y, Eisenberg RJ, Cohen GH, et al. Blocking immune evasion as a novel approach for prevention and treatment of herpes simplex virus infection. Journal of Virology. 2003;77(23):12639–45. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.23.12639-12645.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Lubinski J, Wang L, Mastellos D, Sahu A, Lambris JD, Friedman HM. In vivo role of complement-interacting domains of herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoprotein gC. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1999;190(11):1637–46. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.11.1637. [erratum appears in J Exp Med 2000 Feb 21;191(4):following 746] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Graf LH, Jr., Kaplan P, Silagi S. Efficient DNA-mediated transfer of selectable genes and unselected sequences into differentiated and undifferentiated mouse melanoma clones. Somatic Cell And Molecular Genetics. 1984;10(2):139. doi: 10.1007/BF01534903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Milne RS, Hanna SL, Rux AH, Willis SH, Cohen GH, Eisenberg RJ. Function of herpes simplex virus type 1 gD mutants with different receptor-binding affinities in virus entry and fusion. Journal of Virology. 2003;77(16):8962–72. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.16.8962-8972.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Rixon FJ, McGeoch DJ. Detailed analysis of the mRNAs mapping in the short unique region of herpes simplex virus type 1. Nucleic Acids Research. 1985;13(3):953–73. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.3.953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Hambleton S, Gershon AA. Preventing varicella-zoster disease. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2005;18(1):70–80. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.1.70-80.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Yoon M, Zago A, Shukla D, Spear PG. Mutations in the N termini of herpes simplex virus type 1 and 2 gDs alter functional interactions with the entry/fusion receptors HVEM, nectin-2, and 3-O-sulfated heparan sulfate but not with nectin-1. Journal of Virology. 2003;77(17):9221–31. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.17.9221-9231.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]