Abstract

β-2 microglobulin (β2m) is a globular protein that self-associates into fibrillar amyloid deposits in patients undergoing hemodialysis therapy. Formation of these β-sheet–rich assemblies is a fundamental property of polypeptides that can be triggered by diverse conditions. For β2m, oligomerization into pre-amyloidogenic states occurs in specific response to coordination by Cu2+. Here we report the basis for this self-association at atomic resolution. Metal is not a direct participant in the molecular interface. Rather, binding results in distal alterations enabling the formation of two new surfaces. These interact to form a closed hexameric species. The origins of this include isomerization of a buried and conserved cis-proline previously implicated in the β2m aggregation pathway. The consequences of this isomerization are evident and reveal a molecular basis for the conversion of this robust monomeric protein into an amyloid-competent state.

Homomeric self-association of proteins is a specific process involved in the maintenance and regulation of nearly all cellular activities. Examples range from the dimerization of transmembrane receptors in signaling1 to the extended polymerization of cytoskeleton proteins2. How such associations are controlled is of critical importance, as errors can have pathological consequences such as cancer and neurodegeneration. Mechanisms of control are often allosteric. In the case of actin-filament assembly, for example, the chemical state of the actin-bound nucleotide influences the strength of the inter-subunit contacts3,4. In sickle hemoglobin, crucial elements of the protein interfaces that give rise to pathological filaments are present only in the absence of bound oxygen5. In recent years, the pathological, homomeric self-association of proteins into amyloid fibers has been associated with numerous degenerative diseases, for example, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease and type II diabetes6,7. In many such systems, it is the unmodified wild-type protein that is competent to form self-associated aggregates. Understanding the molecular basis of the triggers of self-association is therefore of paramount importance.

Human β2m is a 99-residue globular protein required for cell-surface expression of class-I major histocompatibility complex (MHC) and MHC-like complexes such as hemochromatosis factor E and fetal Fc receptor. Consequently, β2m knockout can result in compromised immunity and improper regulation of iron homeostasis8,9. In vivo, β2m is released into the serum as a normal part of the turnover of these receptors. β2m circulates in serum at ~0.1 μM until it is catabolized in the kidneys. Notably, in vitro studies of β2m show it can be reversibly folded10–12, and experiments conducted at 100 μM concentration (pH 7.4, 150 mM salt, 37 °C) show no evidence of oligomerization13. NMR studies at even higher concentrations (approximately millimolar) show no loss to aggregation14,15, further supporting the characterization of β2m as a well-behaved, globular protein.

Elevation of β2m levels as much as ten-fold accompanies many infectious and degenerative disorders, including renal failure. However, patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) treated by hemodialysis uniquely suffer from dialysis-related amyloidosis (DRA). In DRA, amyloid composed principally of wild-type, unmodified and noncovalently associated β2m deposits in the joints, resulting in a range of debilitating arthropathies16,17. It is therefore crucial to identify the environmental changes unique to hemodialysis therapy that induce stable β2m to self-assemble. In vitro aggregation conditions include introduction of detergent18, fluorinated alcohols19, acidic pH20, proteolysis21, thermal denaturation22, serum proteins23 and nanoparticulates24.

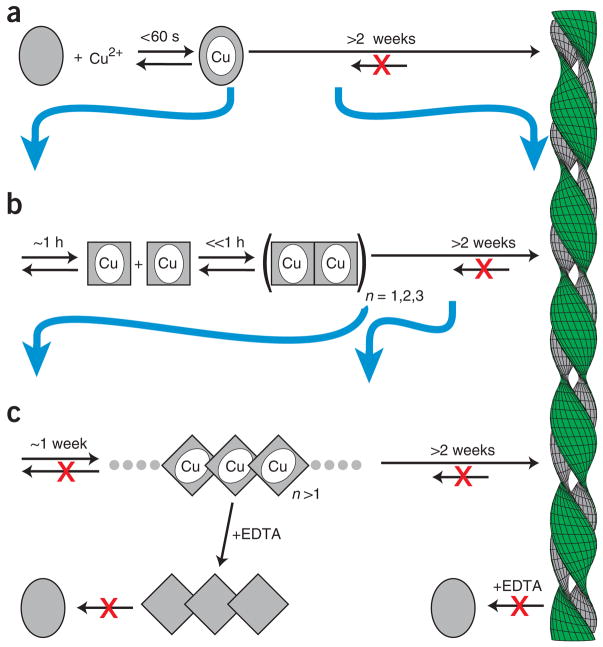

In our own work, we discovered that, under physiological conditions, β2m is a divalent-metal binding protein15 capable of binding Cu2+ or Ni2+. Notably, the Cu2+ but not the Ni2+ holo state is prone to aggregation under physiological solution conditions (Fig. 1a). β2m–Cu2+ populates a bounded set of intermediates before fiber formation and under conditions that strongly favor the native state. The first of these is an alternative monomeric species that arises on a timescale of ~1 h13,25 (Fig. 1b). This state is likely to be similar to a species suggested from refolding studies of β2mapo26. Formation of the activated state is then followed by rapid (≪ 1 h) and reversible self-association to populate dimeric, tetrameric and hexameric states13 (Fig. 1b). Oligomerization has also been reported for β2mapo, albeit under partially denaturing conditions27 at pH ≤3.6. Finally, continued incubation of oligomeric β2m results in the formation of long-lived species that no longer require Cu2+ for stability28,29 (Fig. 1c).

Figure 1.

Model of Cu2+-dependent amyloid formation of β2m. (a) In the absence of metal, β2m exists as a stable monomer (gray oval). The Cu2+ holo form leads to amyloid formation on a timescale of weeks15. (b) The initial Cu2+ binding event is followed by oligomerization on a timescale of ~1 h. The rate-limiting step of this oligomerization is a conformational rearrangement (gray rectangle)13. These oligomers require Cu2+ for stability and dissociate to monomeric form upon addition of a metal chelate (EDTA). (c) Cu2+ acts catalytically, giving rise to chelate-irreversible oligomers in a process that is accelerated by subdenaturing levels of urea comparable to that found in uremic patients28. Chelate resistance persists within the mature fiber.

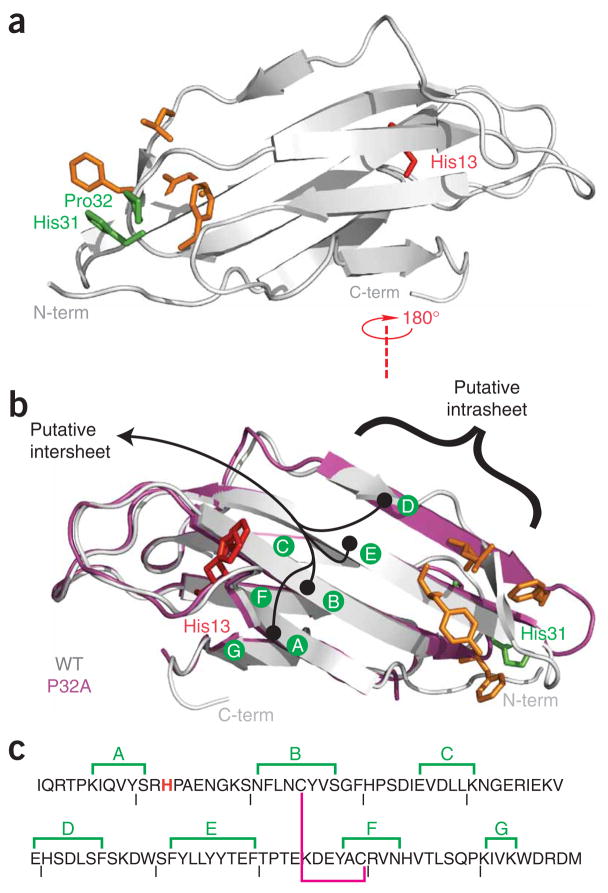

A central residue in the formation of the initial activated state is a conserved cis-proline at position 32. Several independent studies have suggested that a trans conformation at this site is crucial to slow folding, nucleation and subsequent elongation of β2m fibers10,11,25. These insights were achieved in large part by stabilizing a trans conformation at position 32 through mutation. For Cu2+-induced amyloid, this is particularly relevant, as the backbone of Pro32 is proximal to a binding site shown experimentally to include the imidazole side chain of His31 (refs. 30,31; Fig. 2). Mutation of Pro32 to a non-prolyl amino acid (alanine) compels the backbone to adopt a trans conformation. β2m P32A is nevertheless a folded protein that, in the presence of Cu2+, wholly bypasses the slow step of monomer activation that characterizes wild-type oligomerization25.

Figure 2.

Wild-type and P32A β2m. (a,b) Ribbon diagrams of wild-type β2mapo (a,b, gray) and P32Aapo (b, magenta). Two previously proposed interface locations based on P32A are indicated in black25 (b). Notable surface alterations previously reported between the wild-type and the P32A structures are shown in orange. The mutation site in this work is shown in red. Residues 32 and 31 are shown in green. (c) The amino acid sequence of β2m with β-sheets annotated as in b. The magenta line denotes an internal disulfide bond, and the mutated His13 is shown in red.

The structure of P32Aapo revealed several features suggestive of the mechanism of oligomeric assembly25. The first occurs at an edge β-strand (strand D), where a native β-bulge has been lost (Fig. 2). The second is a rearrangement of hydrophobic residues on one of the two exposed faces of this β-sandwich protein. These locations may therefore represent two alternative locations for oligomerization interfaces. A complete understanding of β2m oligomerization requires structural studies of β2mholo. This is challenged by the intrinsic heterogeneity of β2m oligomeric assembly. In this work, we have overcome this problem, and we present structural analysis of a reversible, metal-bound oligomeric state.

RESULTS

Identification of a hydrophobic interface

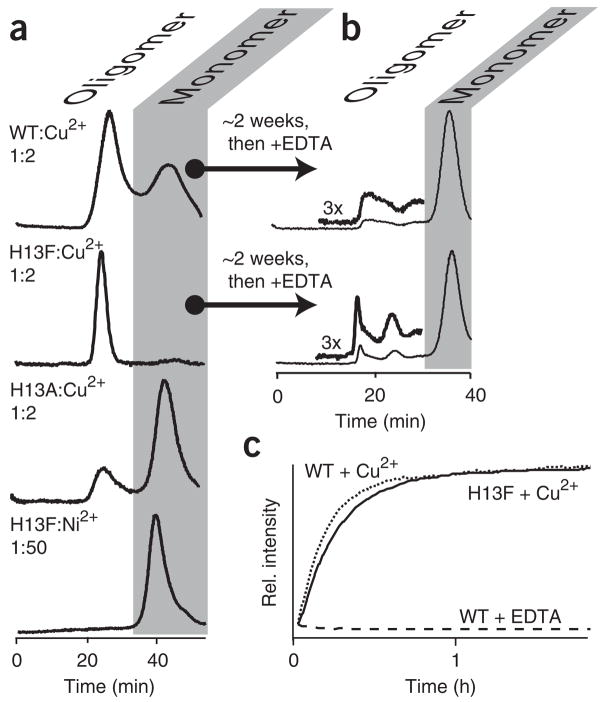

The putative interfaces deduced from the structure of P32A25 were assessed for potential sites that would perturb the extent of oligomerization without affecting mechanism. We selected residue 13 because it is solvent exposed and located in a region that is unperturbed between wild type and P32A (Fig. 2). We have previously shown that, at 100 μM protein and 200 μM Cu2+, wild-type β2mholo forms a distribution of states13 (Fig. 3a). In marked contrast, H13Fholo under the same conditions populates only oligomeric states, whereas mutation of His13 to alanine results in a holo protein that remains principally monomeric. Residue 13, therefore, resides at an interface predominantly stabilized by hydrophobic interactions.

Figure 3.

Metal-dependent aggregation. (a) Size-exclusion chromatography elution profiles of indicated constructs incubated with Cu2+ or Ni2+ present at the indicated stoichiometries. For emphasis, H13F:Ni2+ is shown only with gross excess of Ni2+. Incubation at lower stoichiometries yields similar results. In all cases, the monomer is the only detectable species if EDTA is added after ~2 h of incubation, just before size-exclusion chromatography analysis (not shown). (b) Incubation for ~2 weeks before addition of 10 mM EDTA reveals formation of Cu2+-free oligomeric species28. (c) Kinetics of Cu2+-induced oligomerization were monitored as previously described13 using the change in fluorescence of an exogenously introduced dye, Thioflavin T13. Exponential profiles are observed and fit to rates of 1.1 ± 0.2 × 10−3 s−1 and 1.1 ± 0.1 × 10−3 s−1 for wild type (WT) and H13F, respectively. Profiles have been normalized to the tail of the exponential.

The oligomerization mechanisms of H13F are comparable to those of the wild type. Neither the global folding stability nor Cu2+ binding affinity of β2m are affected by the H13F mutation30. In addition, H13F forms oligomers at a similar rate to the wild type upon exposure to Cu2+ but not Ni2+. Finally, Cu2+ acts catalytically on the wild-type protein, giving rise to chelate (EDTA)-irreversible oligomers28. The extent to which this occurs (~20% of total protein) in H13F is comparable to what is seen with the wild-type protein (Fig. 3b,c). Thus, mutation of His13 has resulted in a protein distinguishable from the wild type only with respect to the stability of initial oligomer formation.

H13Fholo forms a hexamer as determined by equilibrium analytical ultracentrifugation (Supplementary Fig. 1 online). We incubated H13F at three concentrations at pH 7.4 with 200 μM Cu2+. Data were collected at three different speeds and subjected to global analysis32. The simplest model sufficient to fit the data is a two-state, monomer-hexamer equilibrium. Our model did not include an explicit term for the energetic contribution of Cu2+ binding. Therefore, under these conditions, the oligomerization of β2m occurs with an apparent ΔG° of −22 kJ mol−1 per subunit.

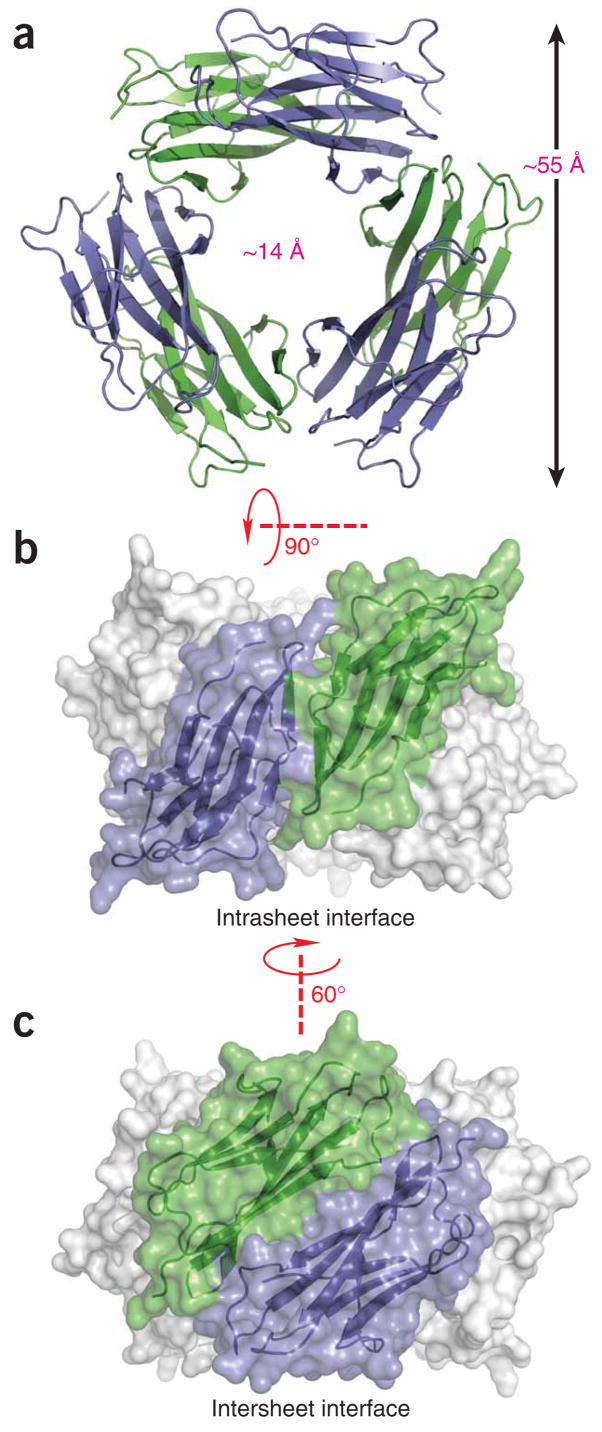

Molecular description of the β2m hexamer

We crystallized hexameric H13Fholo and solved the structure using molecular replacement. The chains are complete between residues 0–97 and give individual structures broadly consistent with the MHC-bound structure (PDB 2CLR33, average Cα r.m.s. deviation 1.5 Å). The hexamer is organized as a hollow ring with an outer diameter of approximately 55 Å and a central solvent-filled channel of approximately 14 Å (Fig. 4). Topologically, each chain forms contacts via distinct interfaces with each of two immediately adjacent subunits. Each interface is approximately two-fold symmetric about axes orthogonal to the central channel, giving a three-fold symmetric hexamer (D3 point-group symmetry). The unit cell is composed of two stacked hexamers with a ~21° deviation between their three-fold axes.

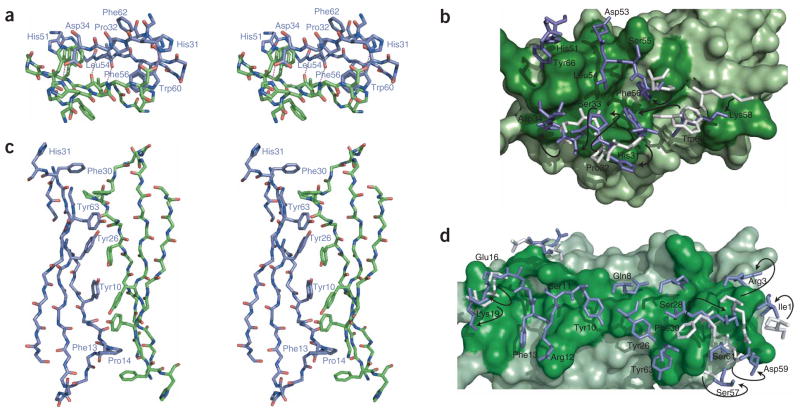

Figure 4.

Solvent-accessible surface and ribbon representations of the β2m hexamer. (a) The hexamer is shown with a view down the threefold rotational axis. Subunits are alternately colored green and blue. (b,c) Two orthogonal side-on views show each of the two intersubunit interfaces, which we refer to as strand-strand (intrasheet; b) and sheet-sheet (intersheet; c), respectively.

The first interface is mediated by the interaction of D-strands from adjacent chains. Hydrogen-bonding occurs between backbone atoms at Leu54 and side chain interactions between Asp34 and His31 (Figs. 4b and 5a,b). Hydrophobic contacts involve Phe56 and Trp60 from one chain sandwiched between nonpolar atoms of His51 and Asp34 from another chain. The overall topology of strand D is similar between wild-type β2mapo and H13Fholo, including the presence of a β-bulge at Asp53. Such edge-strand bulges are generally regarded as protective against aggregation34. This expectation is reflected in reports of β2mapo structures35,36 where, for example, limited contacts have been reported at crystal interfaces37. Here, an interface burying 1,340 Å2 of surface is formed despite this bulge, principally as a result of movement at residues Phe56 and Trp60 upon Cu2+ binding. These side chains are displaced from β2mapo by 3.1 Å and 8.0 Å, respectively, and do not make direct contact with Cu2+-coordinating residues (see below).

Figure 5.

Intersubunit contacts in the β2mholo hexamer. Views of the strand-strand (a,b) and sheet-sheet (c,d) interfaces within the context of the hexamer. Interfaces correspond to the junction between the green and blue chains shown in Figure 4b,c. Stick representations in a and c are shown as wall-eye stereo pairs. Side chains and annotations are shown only for residues discussed in the main text and for only a single subunit, as the interfaces are approximately two-fold symmetric. (b,d) Surface cutaway of the strand-strand (b) and sheet-sheet (d) interfaces. One subunit is represented as a solvent-accessible surface in green, the other with sticks in blue. Dark-green surface residues correspond to interface participants. For interface residues that have moved >2 Å r.m.s. relative to wild-type β2mapo (PDB 2CLR), side chains of wild-type β2mapo are also drawn (gray), with their position in H13Fholo indicated by arrows.

The second interface is mediated by the stacking of the ABED sheet from one chain onto the ABED sheet of an adjacent subunit. Each strand approximately opposes its counterpart (A:A, B:B, and so on) in an antiparallel arrangement that buries 1,950 Å2 of surface area (Fig. 4c). The core of the interface is mediated, in part, by successive contacts between tyrosine residues 63:26:10:10:26:63 forming both aromatic and polar contacts (Fig. 5c,d). This network is flanked further by Phe13. All of the phenol groups are within 2 Å from that observed in wild-type β2mapo, and the mutated side chain overlays the His13 ring of the β2mapo structure (Supplementary Fig. 2 online). Seven interface residues show deviations >2 Å from wild-type β2mapo. These include Ile1, Arg3 and Phe30, which are associated with formation of the Cu2+ binding site and therefore represent the crucial switch enabling oligomerization of β2m (Fig. 5d).

Copper binding is stoichiometric in solution (Supplementary Fig. 3 online) and in the structure. Data for the latter were collected at a Cu2+-anomalous edge to allow unambiguous placement (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Fig. 4 online). Binding is mediated by the imidazole ring of His31 and the carbonyl and amide nitrogen of Ile1. The identification of these residues reconciles earlier analyses that used NMR to identify His31 (refs. 30,31) with studies using Fenton chemistry that suggested a potential role for Ile1 (ref. 38). Notably, we see here that the Ile1 and His31 ligands are derived from the same chain; that is, coordination does not bridge hexamer subunits. The amide nitrogen of Met0 also coordinates; however, studies in which expressed and human-derived proteins have been assayed side-by-side have shown no contribution from the terminal methionine30. We therefore surmise that, at physiological pH, the energetic contribution of Met0 is small and can be substituted by water. Regardless of this, four ligands are available to the Cu2+ and coordinate with a distorted square-planar binding geometry (Fig. 6a, Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 1 online).

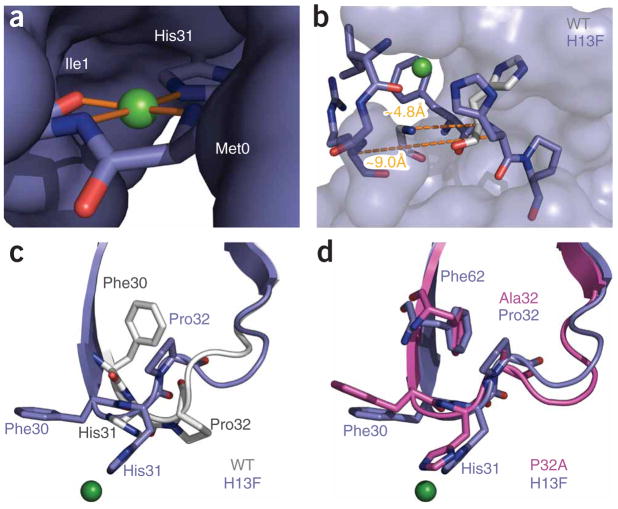

Figure 6.

Conformational effects of Cu2+ binding. (a) Copper (green sphere) shown with its coordinating ligands. The remainder of the protein is shown as solvent-accessible surface. The geometry is approximately square, with the metal cation coplanar with its ligands. Details of the binding-site geometry are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. (b) Strand A is displaced as a result of Cu2+ binding. H13Fholo (blue) is shown as sticks for residues 1–3 of strand A and 30–32 of the BC loop. The remaining residues of H13Fholo are shown as a solvent-accessible surface. His31 and the main chain of Arg3 are shown for the wild-type protein (gray). Dashed lines denote the indicated Cα-Cα separation between residues 3 and 31 of H13Fholo and the wild-type protein, respectively. (c,d) Comparison of the BC loop of H13Fholo with corresponding residues in the wild-type and P32A structures.

Binding is associated with rearrangements both proximal and distal from the coordinating ligands. Strand A is displaced >4 Å from its position in wild-type β2mapo (Fig. 6b). The resultant loss of main chain hydrogen bonding between Arg3 and His31 seems to displace strand A from the BC loop. This may be the prerequisite for accommodating two important alterations. First, the benzyl ring of Phe30 undergoes an >8 Å r.m.s. movement from a wholly buried position to one that is solvent exposed (Fig. 6c). Second, the side chain of Pro32, which populates a conserved cis-conformation in wild-type β2mapo, adopts a trans conformation here. The rearrangements of Phe30 and Pro32 can be spatially connected to a set of distal effects. Notably, the internal cavity left by movement of Phe30 is filled by a 4.4- Å r.m.s. movement of Phe62. The region formerly occupied by Phe62 is then filled by movement of Trp60 and Pro32. Indeed, a new contact is formed between the side chains of Pro32 and Phe62 (Fig. 5a). This contact may account for the approximately tenfold reduced capacity reported for elongation of fibers by the F62A mutant39. In all, the alterations generate a well-defined and alternative hydrophobic core.

DISCUSSION

The binding of a Cu2+ ligand has local and distal structural effects that fundamentally alter the capacity of β2m to oligomerize. Several structural insights have been gained: (i) the site of mutation, His13, resides on an oligomerization interface; (ii) reversible oligomerization of β2mholo terminates in a hexameric state; (iii) the hexamer is a closed ring with symmetric ends and a solvent-filled central channel; (iv) each subunit chain participates in two distinct interfaces; (v) each subunit has a single and independent binding site for Cu2+, that is, Cu2+ does not bridge chains; and (vi) Cu2+ binding results in reorganization of hydrophobic core residues, movement of the first terminal β-strand, and isomerization of a conserved cis-proline to trans. These alterations give rise to the formation of oligomerization interfaces.

The direct observation of a trans conformation at Pro 32 is revealing given the behavior of several reported non-prolyl constructs: P32G11, P32V10 and P32A25. P32V revealed that a slow phase of refolding in the wild-type protein could be eliminated. As partially folded states are generally associated with amyloidogenic species40, this observation prompted the authors to conjecture a role for this conformer in amyloidogenesis. A similar result was later obtained for P32G with global analysis, suggesting the trans conformation is correlated with elongation of amyloid fibers. A trans isomer of Pro32 has also been observed in amyloid structures formed from a fragment (residues 20–41) of β2m41. Our own work with P32A revealed that this mutation eliminates the ~1-h step associated with forming oligomerization-competent conformation(s) of β2mholo25. The trans backbone conformation of this residue is therefore not only pivotal to aggregation, but, given our structure, it is also evidently a state that can be tolerated by wild-type β2m.

A trans conformation at Pro32 is necessary, but not sufficient for oligomerization. Note that the substantial rearrangements observed over residues 29–32 of P32Aapo are identical to those observed here where the site of mutation is distal (Fig. 6c,d). Nevertheless, P32Aapo is predominantly monomeric in solution25. Therefore movement of the terminal strand upon Cu2+ binding may have an additional role in formation of the oligomerization interface. Notable are the formation of interactions between Ile1 and Arg3 with Phe30. This may stabilize the exposed Phe30 in H13Fholo thereby strengthening the Phe30:Pro14 inter-subunit contact (Fig. 5c). As Ile1 and Arg3 are both substantially perturbed by movement of the N terminus to accommodate metal binding, they are a likely additional requirement for metal dependent oligomerization.

Disruption of strand A has previously been associated with amyloid formation by β2m. For example, mutations in the A-strand42, or truncation of six N-terminal residues21 (β2m7-99) give rise to states that, like WTholo, are aggregation prone at neutral pH. We note that strand A docks on the BC loop proximal to Phe30 in WTapo. 1H-NMR studies display the loss of an aromatic contact between Ile35 and Phe30 upon Cu2+ binding25. This contact is likely broken by the rotation of Phe30 from the protein core toward solvent (Fig. 6c). Loss of this contact can similarly be seen in 1H NMR spectra reported for the N-terminally truncated β2m7-99 (ref. 21). Furthermore, in studies of low pH induced aggregation, strand A is reported as highly dynamic while the rest of the protein remains folded43. Other methods of inducing amyloid formation at neutral pH include introduction of SDS18, or TFE19. These too may give rise to partial unfolding at the A-strand. Finally, we note that measures of solvent accessibility suggest that strand A is disrupted in mature fibers44. A recently constructed double mutant, P32G/I7A, supports the joint requirement of BC-loop and A-strand alterations. This mutant can reasonably be expected to both disrupt the docking of strand A (I7A) and bias a trans conformation at position 32 (P32G). The result is a construct that spontaneously forms fibers at physiological pH, without exogenous addition of Cu2+, and that are spectroscopically (infrared) similar to ex vivo–derived β2m fibers45. We surmise that, despite the widely varying conditions reported for inducing amyloid formation by β2m, all result in states that are characterized in part by a trans Pro32, a solvent-exposed Phe30 and a displaced N-terminal strand.

The metal-binding site of the initial β2mholo state (Fig. 1a) is distinct from that found in the initial oligomerizing species reported here (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Fig. 4). In wild-type β2m, the folded stability of the trans conformation of Pro32 is weaker than that of the cis conformation. The former is therefore poorly populated by the apo protein11,25. The energy balance can be shifted by binding a divalent metal cation and forming oligomerization interfaces. A prominent distinction between the P32A mutant and the wild-type protein is that oligomerization by the former can be mediated by Cu2+ or Ni2+, whereas the latter is Cu2+ specific. The distorted square planar geometry of the H13Fholo binding site should be nonspecific. Indeed, if we take the H13Fholo binding site as indicative of the binding site of P32A, then the coordination geometry accounts for the lack of specificity in P32A. Specificity for Cu2+ by the wild-type protein therefore resides in the mechanism of transition from the initial Cu2+-bound state to the oligomerization-competent conformation reported here.

For the structure reported here to adopt irreversible oligomeric states including fibers (Figs. 1c and 3b), further changes are required. H13Fholo and wild-type β2mholo readily dissociate upon chelation of a divalent-metal cation with EDTA. Further transition to an irreversible state occurs gradually over ~1–2 weeks in a process that is accelerated by subdenaturing levels of urea comparable to that found in uremic patients28. There are several possibilities. In β2mholo, there is a β-bulge at Asp53 that is accommodated by the D:D strand interface, but with a crossing angle of ~33°. In P32A25, the β-bulge has been lost enabling a canonical D:D, strand-to-strand crossing angle of ~15°. Other studies have also reported that bulge-free strand-D conformers can be captured by crystallization35,36. A transition between D-strand forms within the hexamer could give rise to greater stability and a breaking of the ring structure with a pitch that enables extended assembly. Alternatively, the interfaces present here may be wholly retained but assembled in an alternative manner. Precedent for this includes SAM domains, which use similar surfaces to generate a range of morphologies including closed oligomers and polymers46. Still other studies on β2m have suggested that FG loop residues are crucial to formation of an amyloid steric zipper47. The FG loops of adjacent β2mholo are brought into proximity by the hexamer and are not interface participants (not shown). Release of the G-strand without dissociation of the hexamer is therefore plausible and would allow the hexamer to create a high effective concentration of the FG loop amyloidogenic sequence. Clearly, this β2mholo structure provides well-defined interactions for delineating these and other possibilities.

In summary, oligomerization of β2m is mediated by a previously undescribed folded conformation. Residues with substantial (>2 Å r.m.s.) deviation from the class I MHC–bound structure are broadly distributed across 26 residues that comprise both exposed and buried moieties. We have previously noted that these residues are conserved and that reversible oligomerization is rapid and specific25,30. Here we have shown that this oligomerization generates a well-defined hexameric state. Pathological aggregation can result when control of functional oligomerization is lost. This has inspired models for polymerization, such as runaway domain swapping48, and may account for the low sequence homology in multisubunit proteins49. Our work here shows that β2m has an intrinsic capacity to oligomerize, allowing this protein to serve as an effective model for both divalent cation–induced allostery and as a structurally characterizable paradigm for amyloid intermediate states.

METHODS

Materials

We obtained protein from Escherichia coli as previously described13 and confirmed its purity by SDS-PAGE and electrospray ionization MS. We assessed the integrity of the intrinsic disulfide by HPLC analysis30. Point mutants were made using Quikchange (Stratagene) and sequencing was verified through the Keck Facility (Yale University). Commonly used buffers and salts are from Sigma-Aldrich and J.T. Baker.

Size-exclusion chromatography

We performed size-exclusion chromatography as previously described28. Briefly, we used an AKTA-prime from Amersham Biosciences and a column with 10 × 300 mm dimensions and a total bed volume of approximately 25 ml packed with Superdex 75. For analysis of chelate-resistant states, we added EDTA to 10 mM to a reaction and incubated this aliquot at 37 °C for ~20 min before size-exclusion chromatography analysis using an EDTA-containing run buffer.

Oligomerization kinetics

We performed kinetic measurements as previously described13. Briefly, we initiated an oligomerization reaction (100 μM protein, 200 μM Cu2+, 25 mM MOPS, 200 mM potassium acetate, pH 7.4, 37 °C) in the presence of a histological dye, Thioflavin T (ThT) at 100 μM. ThT gives an increase in fluorescence intensity upon binding to oligomeric but not monomeric β2m13, allowing oligomerization to be monitored in real time. Measurements were made using a PTI Quantamaster with 4-nm slits. Monochromators were set to 440 nm and 492 nm for excitation and emission, respectively. Data were fit to single exponentials using MATLAB V 7.2.0.232 (The MathWorks Inc.).

Analytical ultracentrifugation

We conducted sedimentation equilibrium analytical ultracentrifugation at 21,000g, 32,000g and 73,000g at 25 °C in a Beckman XL-I Instrument monitored at 280 nm. Samples of H13F were incubated at 10 μM, 30 μM or 90 μM protein (in monomeric units) at 200 μM Cu2+ (pH 7.4) and loaded into six-channel sector-shaped cells. Samples were allowed to equilibrate for ~24 h at each speed. A duplicate array of samples (yielding 18 data sets) was globally fit to a self-association model in Heteroanalysis32. Note that 4 of these 18 data sets were excluded from analysis because they failed to equilibrate as evidenced by WinMatch.

Electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy

We conducted electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) measurements on a Bruker Instruments Elexsys EPR spectrometer operated at 20 K. Samples were approximately 150 μl with 30% (v/v) ethylene glycol as a cryoprotectant. We determined Cu2+concentrations by double integration of EPR spectra.

Crystallization

We initiated an oligomerization reaction under standard reaction conditions13, (see above) with urea omitted from all samples. After hexamer formation (>2 h), we concentrated the reaction to >10 mg ml−1 in a 5000 MWCO centrifugal concentrator. Samples were mixed with crystallization buffer in a 1:1 ratio and incubated at 15 °C in sitting-drop wells. Thin plates generally appeared within 48 h. The crystallization reservoir solution consisted of 28% (w/v) PEG 3350, 200 mM ammonium tartrate dibasic. Crystals were frozen directly from their drop in liquid nitrogen.

Structure determination and refinement

Data were collected at beamline X12B at the National Synchrotron Light Source (NSLS) at Brookhaven National Laboratory (Table 1). The wavelength of incident radiation was 1.37 Å, approximately the anomalous edge of Cu2+. Data were collected and scaled using HKL2000 (ref. 50). Molecular replacement was performed using Phaser51 with 1LDS (residues 0–10, 23–36, 51–96) as the search model35. Model bias was reduced with cycles of prime and switch phasing in Resolve with density modification and noncrystallographic symmetry (NCS) averaging52. Subsequent refinement and rebuilding were carried out in Refmac53 and Coot54, respectively. During scaling and refinement, data were initially included to 2.65 Å and later truncated to 2.9 Å. Scaling statistics are shown in Table 1. Final Rwork and Rfree are 22.5% and 26.4%, respectively. Structure validation was performed using MolProbity55 and PROCHECK56.

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| H13Fholo | |

|---|---|

| Data collection | |

| Space group | P1 |

| Cell dimensions | |

| a, b, c (Å) | 67.6, 68.0, 96.2 |

| α, β, γ(°) | 104.4, 94.2, 117.8 |

| Resolution (Å) | 50–2.9 (3.0–2.9) |

| Rsym | 0.079 (0.363) |

| I/σI | 9.5 (2.6) |

| Completeness (%) | 95.3 (96.2) |

| Redundancy | 2.2 (2.2) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution (Å) | 50–2.9 |

| No. reflections | 28,565 |

| Rwork/Rfree | 22.5, 26.4 |

| No. atoms | 9,934 |

| Protein | 9,830 |

| Ligand/ion | 22 |

| Water | 82 |

| B-factors | |

| Protein | 57.4 |

| Ligand/ion | 91.6 |

| Water | 58.5 |

| R.m.s. deviations | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.006 |

| Bond angles (°) | 0.895 |

Highest-resolution shell is shown in parentheses. One crystal was used for data collection. Statistics and B-factors are calculated based on all atoms in all chains.

Throughout refinement, all chains in the unit cell were treated as near-equivalent using NCS restraints. These restraints were used to prevent over-fitting data, and the strength of restraints was varied empirically until the free R factor was at a minimum57. NCS restraints were applied equally to all 12 chains within the asymmetric unit. Each chain was broken into nine NCS groups principally composed of secondary-structural elements (including both main chain and side chain atoms). Graphics were prepared using PyMol (http://pymol.sourceforge.net/). The unit cell is composed of two hexamers related by noncrystallographic symmetry. All analysis in this paper pertains to only the first hexamer, chains A–F, which show clearer electron density than chains G–L, but statistics from both hexamers are reflected in Table 1. Ambiguous regions in chains G–L were built and refined using NCS restraints and averaged electron-density maps.

Supplementary Material

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Nature Structural & Molecular Biology website.

Acknowledgments

We thank D.M. Engelman, A. Schepartz and G.W. Brudvig for use of instruments and the staff of the Center for Structural Biology and National Synchotron Light Source (NSLS) beamline X12B for assistance and helpful discussions. We are also grateful to Y. Xiong, Y. Modis, A. Berman, A. Valentine, S.A. Strobel, J.C.

Cochrane, C. Craig, D.V. Blaho and A.O. Olivares for assistance and comments. This work was supported by the US National Institutes of Health (DK54899 and 5T32GM07223).

Footnotes

Reprints and permissions information is available online at http://npg.nature.com/reprintsandpermissions/

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.F.C., C.M.E. and A.D.M. designed the experiments; M.F.C. conducted the experiments; M.F.C. and J.M.W. solved and refined the structure; M.F.C. and A.D.M. wrote the paper.

Accession codes. Protein Data Bank: Coordinates and structure factors for the H13Fholo hexamer have been deposited under accession code 3CIQ.

References

- 1.Burgess AW, et al. An open-and-shut case? Recent insights into the activation of EGF/ErbB receptors. Mol Cell. 2003;12:541–552. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00350-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pollard TD, Borisy GG. Cellular motility driven by assembly and disassembly of actin filaments. Cell. 2003;112:453–465. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00120-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Egelman EH, Orlova A. Allostery, cooperativity, and different structural states in F-actin. J Struct Biol. 1995;115:159–162. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1995.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frederick KB, Sept D, De La Cruz EM. Effects of solution crowding on actin polymerization reveal the energetic basis for nucleotide-dependent filament stability. J Mol Biol. 2008;378:540–550. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sunshine HR, Hofrichter J, Ferrone FA, Eaton WA. Oxygen binding by sickle cell hemoglobin polymers. J Mol Biol. 1982;158:251–273. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90432-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rochet JC, Lansbury PT., Jr Amyloid fibrillogenesis: themes and variations. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2000;10:60–68. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(99)00049-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiti F, Dobson CM. Protein misfolding, functional amyloid, and human disease. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:333–366. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.101304.123901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Santos M, et al. Defective iron homeostasis in beta 2-microglobulin knockout mice recapitulates hereditary hemochromatosis in man. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1975–1985. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.5.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drake DR, III, Lukacher AE. β2-microglobulin knockout mice are highly susceptible to polyoma virus tumorigenesis. Virology. 1998;252:275–284. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kameda A, et al. Nuclear magnetic resonance characterization of the refolding intermediate of β2-microglobulin trapped by non-native prolyl peptide bond. J Mol Biol. 2005;348:383–397. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jahn TR, Parker MJ, Homans SW, Radford SE. Amyloid formation under physiological conditions proceeds via a native-like folding intermediate. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:195–201. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiti F, et al. Detection of two partially structured species in the folding process of the amyloidogenic protein β2-microglobulin. J Mol Biol. 2001;307:379–391. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eakin CM, Attenello FJ, Morgan CJ, Miranker AD. Oligomeric assembly of native-like precursors precedes amyloid formation by β2 microglobulin. Biochemistry. 2004;43:7808–7815. doi: 10.1021/bi049792q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okon M, Bray P, Vucelic D. 1H NMR assignments and secondary structure of human β2-microglobulin in solution. Biochemistry. 1992;31:8906–8915. doi: 10.1021/bi00152a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morgan CJ, Gelfand M, Atreya C, Miranker AD. Kidney dialysis-associated amyloidosis: a molecular role for copper in fiber formation. J Mol Biol. 2001;309:339–345. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Floege J, Ehlerding G. β2-microglobulin-associated amyloidosis. Nephron. 1996;72:9–26. doi: 10.1159/000188801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Menaa C, Esser E, Sprague SM. β2-microglobulin stimulates osteoclast formation. Kidney Int. 2008;73:1275–1281. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamamoto S, et al. Low concentrations of sodium dodecyl sulfate induce the extension of β2-microglobulin-related amyloid fibrils at a neutral pH. Biochemistry. 2004;43:11075–11082. doi: 10.1021/bi049262u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamamoto S, et al. Glycosaminoglycans enhance the trifluoroethanol-induced extension of β2-microglobulin-related amyloid fibrils at a neutral pH. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:126–133. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000103228.81623.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McParland VJ, et al. Partially unfolded states of β2-microglobulin and amyloid formation in vitro. Biochemistry. 2000;39:8735–8746. doi: 10.1021/bi000276j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Esposito G, et al. Removal of the N-terminal hexapeptide from human β2-microglobulin facilitates protein aggregation and fibril formation. Protein Sci. 2000;9:831–845. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.5.831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sasahara K, Yagi H, Naiki H, Goto Y. Heat-induced conversion of β2-microglobulin and hen egg-white lysozyme into amyloid fibrils. J Mol Biol. 2007;372:981–991. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.06.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Myers SL, et al. A systematic study of the effect of physiological factors on β2-microglobulin amyloid formation at neutral pH. Biochemistry. 2006;45:2311–2321. doi: 10.1021/bi052434i. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Linse S, et al. Nucleation of protein fibrillation by nanoparticles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:8691–8696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701250104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eakin CM, Berman AJ, Miranker AD. A native to amyloidogenic transition regulated by a backbone trigger. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:202–208. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dobson CM. An accidental breach of a protein’s natural defenses. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:295–297. doi: 10.1038/nsmb0406-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith AM, Jahn TR, Ashcroft AE, Radford SE. Direct observation of oligomeric species formed in the early stages of amyloid fibril formation using electrospray ionisation mass spectrometry. J Mol Biol. 2006;364:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.08.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Calabrese MF, Miranker AD. Formation of a stable oligomer of β2 microglobulin requires only transient encounter with Cu(II) J Mol Biol. 2007;367:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Antwi K, et al. Cu(II) organizes β2-microglobulin oligomers but is released upon amyloid formation. Protein Sci. 2008;17:748–759. doi: 10.1110/ps.073249008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eakin CM, Knight JD, Morgan CJ, Gelfand MA, Miranker AD. Formation of a copper specific binding site in non-native states of β2-microglobulin. Biochemistry. 2002;41:10646–10656. doi: 10.1021/bi025944a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Verdone G, et al. The solution structure of human β2-microglobulin reveals the prodromes of its amyloid transition. Protein Sci. 2002;11:487–499. doi: 10.1110/ps.29002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cole JL. Analysis of heterogeneous interactions. Methods Enzymol. 2004;384:212–232. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)84013-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bjorkman PJ, et al. Structure of the human class I histocompatibility antigen, HLA-A2. Nature. 1987;329:506–512. doi: 10.1038/329506a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Richardson JS, Richardson DC. Natural β-sheet proteins use negative design to avoid edge-to-edge aggregation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:2754–2759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052706099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trinh CH, Smith DP, Kalverda AP, Phillips SE, Radford SE. Crystal structure of monomeric human β2-microglobulin reveals clues to its amyloidogenic properties. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:9771–9776. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152337399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Iwata K, Matsuura T, Sakurai K, Nakagawa A, Goto Y. High-resolution crystal structure of β2-microglobulin formed at pH 7.0. J Biochem. 2007;142:413–419. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvm148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosano C, et al. β2-microglobulin H31Y variant 3D structure highlights the protein natural propensity towards intermolecular aggregation. J Mol Biol. 2004;335:1051–1064. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lim J, Vachet RW. Using mass spectrometry to study copper-protein binding under native and non-native conditions: β2-microglobulin. Anal Chem. 2004;76:3498–3504. doi: 10.1021/ac049716t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Platt GW, Routledge KE, Homans SW, Radford SE. Fibril growth kinetics reveal a region of β2-microglobulin important for nucleation and elongation of aggregation. J Mol Biol. 2008;378:251–263. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.01.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dobson CM. Protein folding and misfolding. Nature. 2003;426:884–890. doi: 10.1038/nature02261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Iwata K, et al. 3D structure of amyloid protofilaments of β2-microglobulin fragment probed by solid-state NMR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:18119–18124. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607180103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jones S, Smith DP, Radford SE. Role of the N and C-terminal strands of β2-microglobulin in amyloid formation at neutral pH. J Mol Biol. 2003;330:935–941. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00688-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McParland VJ, Kalverda AP, Homans SW, Radford SE. Structural properties of an amyloid precursor of β2-microglobulin. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9:326–331. doi: 10.1038/nsb791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hoshino M, et al. Mapping the core of the β2-microglobulin amyloid fibril by H/D exchange. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9:332–336. doi: 10.1038/nsb792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jahn TR, Tennent GA, Radford SE. A common β-sheet architecture underlies in vitro and in vivo β2-microglobulin amyloid fibrils. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:17279–17286. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710351200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ramachander R, Bowie JU. SAM domains can utilize similar surfaces for the formation of polymers and closed oligomers. J Mol Biol. 2004;342:1353–1358. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ivanova MI, Sawaya MR, Gingery M, Attinger A, Eisenberg D. An amyloid-forming segment of β2-microglobulin suggests a molecular model for the fibril. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:10584–10589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403756101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bennett MJ, Schlunegger MP, Eisenberg D. 3D domain swapping: a mechanism for oligomer assembly. Protein Sci. 1995;4:2455–2468. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560041202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wright CF, Teichmann SA, Clarke J, Dobson CM. The importance of sequence diversity in the aggregation and evolution of proteins. Nature. 2005;438:878–881. doi: 10.1038/nature04195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Storoni LC, McCoy AJ, Read RJ. Likelihood-enhanced fast rotation functions. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:432–438. doi: 10.1107/S0907444903028956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Terwilliger TC. Maximum-likelihood density modification. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2000;56:965–972. doi: 10.1107/S0907444900005072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4. The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lovell SC, et al. Structure validation by Cα geometry: φ, ψ and Cα deviation. Proteins. 2003;50:437–450. doi: 10.1002/prot.10286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Laskowski R, MacArthur M, Moss D, Thornton J. PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J Appl Crystallogr. 1993;26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kleywegt GJ, Brunger AT. Checking your imagination: applications of the free R value. Structure. 1996;4:897–904. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(96)00097-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Nature Structural & Molecular Biology website.